Thomas Carlyle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

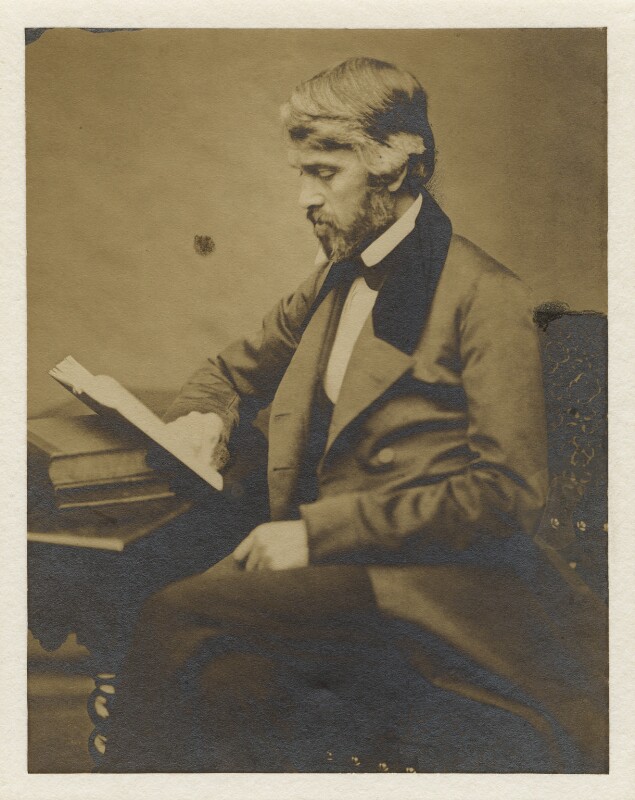

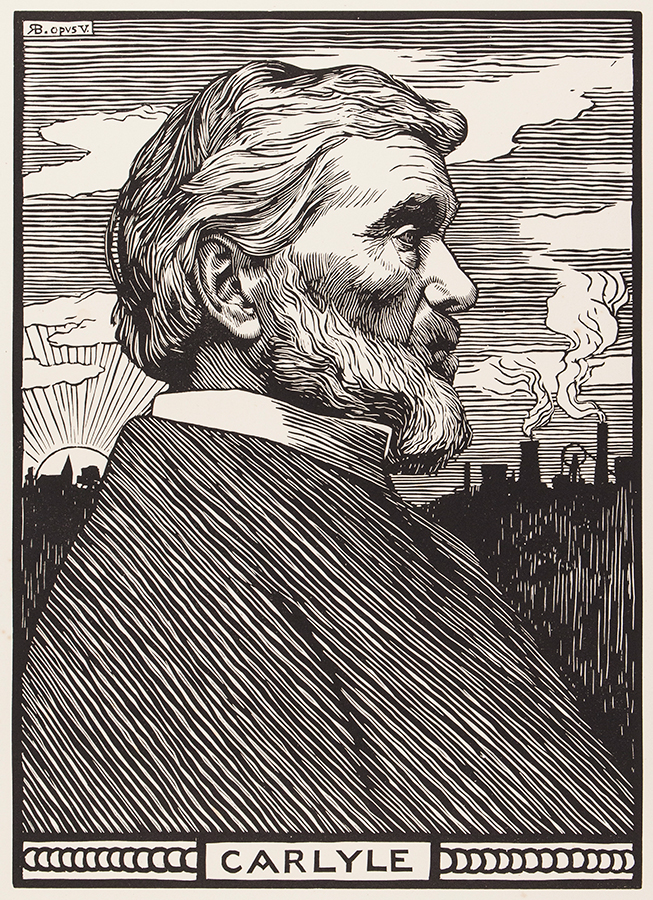

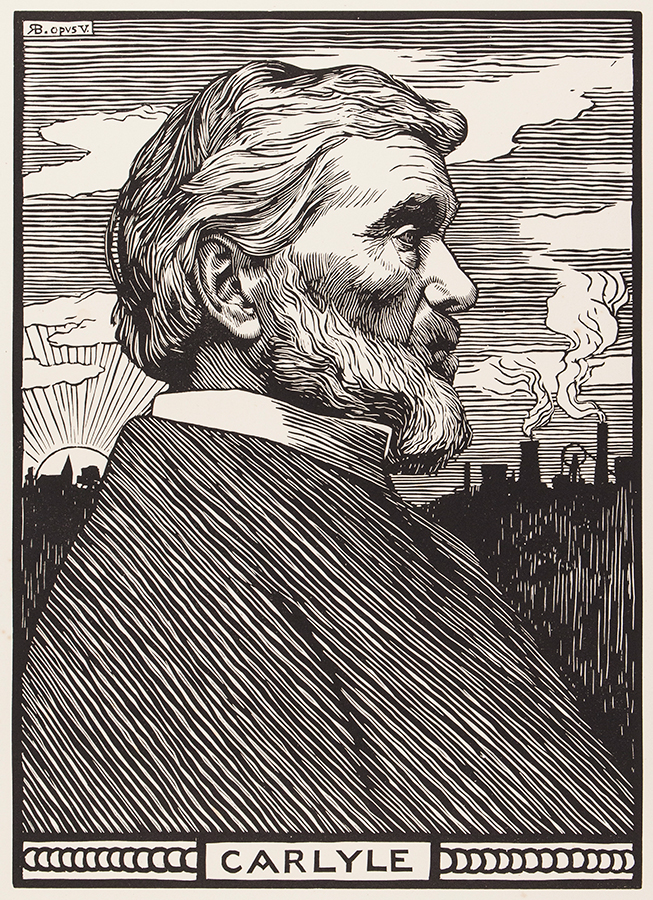

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the " sage of Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the

Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review">Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review'', and shortly afterwards began a tutorship for the distinguished Buller family, tutoring Charles Buller and his brother Arthur William Buller until July; he would work for the family until July 1824. Carlyle completed the Legendre translation in July 1822, having prefixed his own essay "On Proportionality (mathematics), Proportion", which Augustus De Morgan later called "as good a substitute for the fifth Book of Euclid as could have been given in that space".

Carlyle's translation of Goethe's ''

Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review">Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review'', and shortly afterwards began a tutorship for the distinguished Buller family, tutoring Charles Buller and his brother Arthur William Buller until July; he would work for the family until July 1824. Carlyle completed the Legendre translation in July 1822, having prefixed his own essay "On Proportionality (mathematics), Proportion", which Augustus De Morgan later called "as good a substitute for the fifth Book of Euclid as could have been given in that space".

Carlyle's translation of Goethe's ''

In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834. He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of Werner", "Goethe's Helena", "Goethe", "Robert Burns, Burns", "The Life of Heyne" (each 1828), "German Playwrights", "Voltaire", "Novalis" (each 1829), "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter Again" (1830), "Cruthers and Jonson; or The Outskirts of Life: A True Story", "Luther's Psalm", and "Schiller" (each 1831). He began but did not complete a history of German literature, from which he drew material for essays "The Nibelungen Lied", "Early German Literature" and parts of "Historic Survey of German Poetry" (each 1831). He published early thoughts on the philosophy of history in "Thoughts on History" (1830) and wrote his first pieces of social criticism, "Signs of the Times" (1829) and "Characteristics" (1831).D. Daiches (ed.), ''Companion to Literature 1'' (London, 1965), p. 89. "Signs" garnered the interest of Gustave d'Eichthal, a member of the Saint-Simonians, who sent Carlyle Saint-Simonian literature, including Henri de Saint-Simon's ''Nouveau Christianisme'' (1825), which Carlyle translated and wrote an introduction for.

In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834. He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of Werner", "Goethe's Helena", "Goethe", "Robert Burns, Burns", "The Life of Heyne" (each 1828), "German Playwrights", "Voltaire", "Novalis" (each 1829), "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter Again" (1830), "Cruthers and Jonson; or The Outskirts of Life: A True Story", "Luther's Psalm", and "Schiller" (each 1831). He began but did not complete a history of German literature, from which he drew material for essays "The Nibelungen Lied", "Early German Literature" and parts of "Historic Survey of German Poetry" (each 1831). He published early thoughts on the philosophy of history in "Thoughts on History" (1830) and wrote his first pieces of social criticism, "Signs of the Times" (1829) and "Characteristics" (1831).D. Daiches (ed.), ''Companion to Literature 1'' (London, 1965), p. 89. "Signs" garnered the interest of Gustave d'Eichthal, a member of the Saint-Simonians, who sent Carlyle Saint-Simonian literature, including Henri de Saint-Simon's ''Nouveau Christianisme'' (1825), which Carlyle translated and wrote an introduction for.

Most notably, he wrote ''

Most notably, he wrote ''

Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in '' Fraser's Magazine'', with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory. That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the French Revolution and set about researching and writing it shortly thereafter. Having completed the first volume after five months of writing, he lent the manuscript to Mill, who had been supplying him with materials for his research. One evening in March 1835, Mill arrived at Carlyle's door appearing "unresponsive, pale, the very picture of despair". He had come to tell Carlyle that the manuscript was destroyed. It had been "left out", and Mill's housemaid took it for wastepaper, leaving only "some four tattered leaves". Carlyle was sympathetic: "I can be angry with no one; for they that were concerned in it have a far deeper sorrow than mine: it is purely the hand of Providence". The next day, Mill offered Carlyle , of which he would only accept £100. He began the volume anew shortly afterwards. Despite an initial struggle, he was not deterred, feeling like "a runner that tho' ''tripped'' down, will not lie there, but rise and run again." By September, the volume was rewritten. That year, he wrote a eulogy for his friend, "Death of Edward Irving".

In April 1836, with the intercession of Emerson, ''Sartor Resartus'' was first published in book form in Boston, soon selling out its initial run of five hundred copies. Carlyle's three-volume history of the French Revolution was completed in January 1837 and sent to the press. Contemporaneously, the essay "Memoirs of Mirabeau" was published, as was " The Diamond Necklace" in January and February, and "Parliamentary History of the French Revolution" in April. In need of further financial security, Carlyle began a series of lectures on German literature in May, delivered extemporaneously in Willis' Rooms. ''

Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in '' Fraser's Magazine'', with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory. That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the French Revolution and set about researching and writing it shortly thereafter. Having completed the first volume after five months of writing, he lent the manuscript to Mill, who had been supplying him with materials for his research. One evening in March 1835, Mill arrived at Carlyle's door appearing "unresponsive, pale, the very picture of despair". He had come to tell Carlyle that the manuscript was destroyed. It had been "left out", and Mill's housemaid took it for wastepaper, leaving only "some four tattered leaves". Carlyle was sympathetic: "I can be angry with no one; for they that were concerned in it have a far deeper sorrow than mine: it is purely the hand of Providence". The next day, Mill offered Carlyle , of which he would only accept £100. He began the volume anew shortly afterwards. Despite an initial struggle, he was not deterred, feeling like "a runner that tho' ''tripped'' down, will not lie there, but rise and run again." By September, the volume was rewritten. That year, he wrote a eulogy for his friend, "Death of Edward Irving".

In April 1836, with the intercession of Emerson, ''Sartor Resartus'' was first published in book form in Boston, soon selling out its initial run of five hundred copies. Carlyle's three-volume history of the French Revolution was completed in January 1837 and sent to the press. Contemporaneously, the essay "Memoirs of Mirabeau" was published, as was " The Diamond Necklace" in January and February, and "Parliamentary History of the French Revolution" in April. In need of further financial security, Carlyle began a series of lectures on German literature in May, delivered extemporaneously in Willis' Rooms. '' In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as '' On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History.'' Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of 'sic''with sufficient ''éclat;'' the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad ''best'' I have yet given." In the 1840 edition of the ''Essays'', Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833. Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh. Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841. He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books,

In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as '' On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History.'' Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of 'sic''with sufficient ''éclat;'' the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad ''best'' I have yet given." In the 1840 edition of the ''Essays'', Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833. Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh. Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841. He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books,

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy as a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland. Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in ''

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy as a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland. Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in ''

James Anthony Froude recalled his first impression of Carlyle:

James Anthony Froude recalled his first impression of Carlyle:

XVIII. Carlyle

. ''The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson''. Vol. X. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company (published 1904). Paul Elmer More found Carlyle "a figure unique, isolated, domineering—after Dr. Johnson the greatest personality in English letters, possibly even more imposing than that acknowledged dictator."

George Eliot summarised Carlyle's impact in 1855:

George Eliot summarised Carlyle's impact in 1855:

Politically, Carlyle's influence spans across ideologies, from conservatism and nationalism to communism. He is acknowledged as an essential influence on

Politically, Carlyle's influence spans across ideologies, from conservatism and nationalism to communism. He is acknowledged as an essential influence on

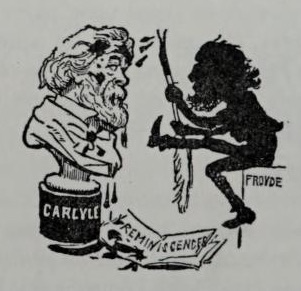

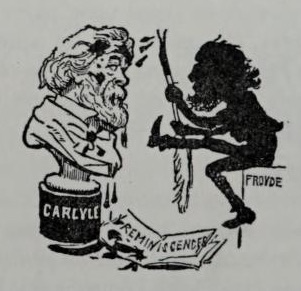

Carlyle had entrusted his papers to the care of James Anthony Froude after his death but was unclear about the permissions granted to him. Froude edited and published the '' Reminiscences'' in 1881, which sparked controversy due to Froude's failure to excise comments that might offend living persons, as was common practice at the time. The book damaged Carlyle's reputation, as did the following ''Letters and Memorials of Jane Welsh Carlyle'' and the four-volume biography of life as written by Froude. The image that Froude presented of Carlyle and his marriage was highly negative, prompting new editions of the ''Reminiscences'' and the letters by Charles Eliot Norton and Alexander Carlyle (husband of Carlyle's niece), who argued that, among other things, Froude had mishandled the materials entrusted to him in a deliberate and dishonest manner. This argument overshadowed Carlyle's work for decades. Owen Dudley Edwards remarked that by the turn of the century, "Carlyle was known more than read". As Campbell describes:

Carlyle had entrusted his papers to the care of James Anthony Froude after his death but was unclear about the permissions granted to him. Froude edited and published the '' Reminiscences'' in 1881, which sparked controversy due to Froude's failure to excise comments that might offend living persons, as was common practice at the time. The book damaged Carlyle's reputation, as did the following ''Letters and Memorials of Jane Welsh Carlyle'' and the four-volume biography of life as written by Froude. The image that Froude presented of Carlyle and his marriage was highly negative, prompting new editions of the ''Reminiscences'' and the letters by Charles Eliot Norton and Alexander Carlyle (husband of Carlyle's niece), who argued that, among other things, Froude had mishandled the materials entrusted to him in a deliberate and dishonest manner. This argument overshadowed Carlyle's work for decades. Owen Dudley Edwards remarked that by the turn of the century, "Carlyle was known more than read". As Campbell describes:

Ireland and Sir Robert Peel

' (1849) * ''Legislation for Ireland'' (1849) *

Ireland and the British Chief Governor

' (1849) * Froude, James Anthony, ed. (1881). ''Reminiscences''. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. * ''Reminiscences of My Irish Journey in 1849'' (1882). London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. * ''Last Words of Thomas Carlyle: On Trades-Unions, Promoterism and the Signs of the Times'' (1882). 67 Princes Street, Edinburgh: William Paterson. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1883). '' The Correspondence of Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo Emerson''. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1886). ''Early Letters of Thomas Carlyle''. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. * ''Thomas Carlyle's Counsels to a Literary Aspirant: A Hitherto Unpublished Letter of 1842 and What Came of Them'' (1886). Edinburgh: James Thin, South Bridge. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1887). ''Reminiscences''. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1887). ''Correspondence Between Goethe and Carlyle''. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1888). ''Letters of Thomas Carlyle''. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. * ''Thomas Carlyle on the Repeal of the Union'' (1889). London: Field & Tuer, the Leadenhall Press. * Newberry, Percy, ed. (1892). ''Rescued Essays of Thomas Carlyle''. The Leadenhall Press. * ''Last Words of Thomas Carlyle'' (1892). London: Longmans, Green, and Co. * Karkaria, R. P., ed. (1892). ''Lectures on the History of Literature''. London: Curwen, Kane & Co. * Greene, J. Reay, ed. (1892). ''Lectures on the History of Literature''. London: Ellis and Elvey. * Carlyle, Alexander, ed. (1898). ''Historical Sketches of Notable Persons and Events in the Reigns of James I and Charles I''. London: Chapman and Hall Limited. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1898). ''Two Note Books of Thomas Carlyle''. New York: The Grolier Club. * Copeland, Charles Townsend, ed. (1899). ''Letters of Thomas Carlyle to His Youngest Sister''. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. * Jones, Samuel Arthur, ed. (1903). ''Collecteana''. Canton, Pennsylvania: The Kirgate Press. * Carlyle, Alexander, ed. (1904). ''New Letters of Thomas Carlyle''. London: The Bodley Head. * * * Carlyle, Alexander, ed. (1923). ''Letters of Thomas Carlyle to John Stuart Mill, John Sterling and Robert Browning''. London: T. Fisher Unwin LTD. * Brooks, Richard Albert Edward, ed. (1940). ''Journey to Germany, Autumn 1858''. New Haven: Yale University Press. * Graham Jr., John, ed. (1950). ''Letters of Thomas Carlyle to William Graham''. Princeton: Princeton University Press. * Shine, Hill, ed. (1951). ''Carlyle's Unfinished History of German Literature''. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press. * Bliss, Trudy, ed. (1953). ''Letters to His Wife''. London:

"Recollections of Carlyle"

''The New Princeton Review''. 2 (4): 1–19. * * * The Westminster Gazette. ''The Homes and Haunts of Thomas Carlyle'', 1895.

Carlyle and the Search for Authority

'. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. * * * *

''Carlyle Studies Annual''

on

The Norman and Charlotte Strouse Edition of the Writings of Thomas Carlyle

''The Collected Letters of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle''

The Carlyle Society of Edinburgh

The Ecclefechan Carlyle Society

Thomas & Jane Carlyle's Craigenputtock

the official site *

at PoetryFoundation.org

''The Carlyle Letters Online''

* '' The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily''

Thomas Carlyle's translation (1832) from the German of Goethe's ''Märchen or Das Märchen''

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle Photographs

at the Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collections {{DEFAULTSORT:Carlyle, Thomas 1795 births 1881 deaths 19th-century Scottish biographers 19th-century British essayists 19th-century Scottish historians 19th-century Scottish translators 19th-century Scottish novelists 19th-century Scottish philosophers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Anti-Masonry Antisemitism in the United Kingdom British anti-communists Conservatism in the United Kingdom Critics of political economy Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Historians of the French Revolution British lecturers British white supremacists People associated with the National Portrait Gallery People educated at Annan Academy People from Dumfries and Galloway People of the Victorian era Scottish proslavery activists Racism in the United Kingdom Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Rectors of the University of Edinburgh Right-wing politics in the United Kingdom Romantic critics of political economy Scottish biographers Scottish essayists 19th-century Scottish mathematicians Scottish literary critics Scottish monarchists Scottish satirists Scottish white nationalists Sexism in the United Kingdom Translators of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Writers of the Romantic era Scottish encyclopedists

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

.

Carlyle was born in Ecclefechan, a village in Dumfriesshire

Dumfriesshire or the County of Dumfries or Shire of Dumfries () is a Counties of Scotland, historic county and registration county in southern Scotland. The Dumfries lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area covers a similar area to the hi ...

. He attended the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

where he excelled in mathematics and invented the Carlyle circle

In mathematics, a Carlyle circle is a certain circle in a coordinate plane associated with a quadratic equation; it is named after Thomas Carlyle. The circle has the property that the equation solving, solutions of the quadratic equation are the ho ...

. After finishing the arts course, he prepared to become a minister in the Burgher Church while working as a schoolmaster. He quit these and several other endeavours before settling on literature, writing for the '' Edinburgh Encyclopædia'' and working as a translator. He initially gained prominence in English-language literary circles for his extensive writing on German Romantic literature and philosophy. These themes were explored in his first major work, a semi-autobiographical philosophical novel entitled ''Sartor Resartus

''Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books'' is a novel by the Scottish people, Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in ''Fraser's Magazine'' in November 1833 ...

'' (1833–34).

Carlyle eventually relocated to London, where he published '' The French Revolution: A History'' (1837). Its popular success made him a celebrity, prompting the collection and reissue of his earlier essays under the title of '' Miscellanies''. His subsequent works were highly regarded throughout Europe and North America, including '' On Heroes'' (1841), ''Past and Present'' (1843), '' Cromwell's Letters'' (1845), '' Latter-Day Pamphlets'' (1850), and '' Frederick the Great'' (1858–65). He founded the London Library, helped establish the National Portrait Galleries in London and in Edinburgh, became Lord Rector of the University of Edinburgh in 1865, and received the '' Pour le Mérite'' in 1874 among other honours.

Carlyle occupied a central position in Victorian culture, being considered the "undoubted head of English letters" and a "secular prophet". Posthumously, a series of publications by his friend James Anthony Froude damaged Carlyle's reputation, provoking controversy about his personal life and his marriage to Jane Welsh Carlyle in particular. His reputation further declined in the aftermaths of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, when his philosophy was seen as a precursor of both Prussianism and fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

. Growing scholarship in the field of Carlyle studies since the 1950s has improved his standing, and though little-read today, he is yet recognised as "one of the enduring monuments of nglishliterature".

Biography

Early life

Thomas Carlyle was born on 4 December 1795 to James and Margaret Aitken Carlyle in the village of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire in southwest Scotland. His parents were members of the Burgher secessionPresbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

church. James Carlyle was a stonemason, later a farmer, who built the Arched House wherein his son was born. His maxim

Maxim or Maksim may refer to:

Entertainment

*Maxim (magazine), ''Maxim'' (magazine), an international men's magazine

** Maxim (Australia), ''Maxim'' (Australia), the Australian edition

** Maxim (India), ''Maxim'' (India), the Indian edition

*Maxim ...

was that "man was created to work, not to speculate, or feel, or dream." Nicholas Carlisle, an English antiquary, traced his ancestry back to Margaret Bruce, sister of Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (), was King of Scots from 1306 until his death in 1329. Robert led Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence against Kingdom of Eng ...

.

As a result of his disordered upbringing, James Carlyle became deeply religious in his youth, reading many books of sermons and doctrinal arguments throughout his life. In 1791, he married his first wife, distant cousin Janet, who gave birth to John Carlyle and then died. He married Margaret Aitken in 1795, a poor farmer's daughter then working as a servant. They had nine children, of whom Thomas was the eldest. Margaret was pious and devout and hoped that Thomas would become a minister. She was close to her eldest son, being a "smoking companion, counsellor and confidante" in Carlyle's early days. She suffered a manic episode when Carlyle was a teenager, in which she became "elated, disinhibited, over-talkative and violent." She suffered another breakdown in 1817, which required her to be removed from her home and restrained. Carlyle always spoke highly of his parents, and his character was deeply influenced by both of them.

Carlyle's early education came from his mother, who taught him reading (despite being barely literate), and his father, who taught him arithmetic. He first attended "Tom Donaldson's School" in Ecclefechan followed by Hoddam School (), which "then stood at the Kirk", located at the "Cross-roads" midway between Ecclefechan and Hoddam Castle

Hoddom Castle is a large tower house in Dumfries and Galloway, south Scotland. It is located by the River Annan, south-west of Ecclefechan and the same distance north-west of Brydekirk in the parish of Cummertrees. The castle is protected as a ...

. By age 7, Carlyle showed enough proficiency in English that he was advised to "go into Latin", which he did with enthusiasm; however, the schoolmaster at Hoddam did not know Latin, so he was handed over to a minister that did, with whom he made a "rapid & sure way". He then went to Annan Academy (), where he studied rudimentary Greek, read Latin and French fluently, and learned arithmetic "thoroughly well". Carlyle was severely bullied by his fellow students at Annan, until he "revolted against them, and gave stroke for stroke"; he remembered the first two years there as among the most miserable of his life.

Edinburgh, the ministry and teaching (1809–1818)

In November 1809 at nearly fourteen years of age, Carlyle walked one hundred miles from his home in order to attend theUniversity of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

(), where he studied mathematics with John Leslie, science with John Playfair and moral philosophy with Thomas Brown. He gravitated to mathematics and geometry and displayed great talent in those subjects, being credited with the invention of the Carlyle circle

In mathematics, a Carlyle circle is a certain circle in a coordinate plane associated with a quadratic equation; it is named after Thomas Carlyle. The circle has the property that the equation solving, solutions of the quadratic equation are the ho ...

. In the University library, he read many important works of eighteenth-century and contemporary history, philosophy, and '' belles-lettres''. He began expressing religious scepticism around this time, asking his mother to her horror, "Did God Almighty come down and make wheelbarrows in a shop?" In 1813 he completed his arts curriculum and enrolled in a theology course at Divinity Hall the following academic year. This was to be the preliminary of a ministerial career.

Carlyle began teaching at Annan Academy in June 1814. In December 1814 and December 1815, he gave his first trial sermons, both of which are lost. By the summer of 1815 he had taken an interest in astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

and would study the astronomical theories of Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

for several years. In November 1816, he began teaching at Kirkcaldy

Kirkcaldy ( ; ; ) is a town and former royal burgh in Fife, on the east coast of Scotland. It is about north of Edinburgh and south-southwest of Dundee. The town had a recorded population of 49,460 in 2011, making it Fife's second-largest s ...

, having left Annan. There, he made friends with Edward Irving, whose ex-pupil Margaret Gordon became Carlyle's "first love". In May 1817, Carlyle abstained from enrolment in the theology course, news which his parents received with " magnanimity". In the autumn of that year, he read '' De l'Allemagne'' (1813) by Germaine de Staël, which prompted him to seek a German teacher, with whom he learned the pronunciation. In Irving's library, he read the works of David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

and Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English essayist, historian, and politician. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, is known for ...

's ''Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'' (1776–1789); he would later recall that I read Gibbon, and then first clearly saw thatChristianity Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...was not true. Then came the most trying time of my life. I should either have gone mad or made an end of myself had I not fallen in with some very superior minds.

Mineralogy, law and first publications (1818–1821)

In the summer of 1818, following an expedition with Irving through the moors of Peebles and Moffat, Carlyle made his first attempt at publishing, forwarding an article describing what he saw to the editor of an Edinburgh magazine, which was not published and is now lost. In October, Carlyle resigned from his position at Kirkcaldy, and left for Edinburgh in November. Shortly before his departure, he began to suffer from dyspepsia, which remained with him throughout his life. He enrolled in amineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...

class from November 1818 to April 1819, attending lectures by Robert Jameson

image:Robert Jameson.jpg, Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE (11 July 1774 – 19 April 1854) was a Scottish natural history, naturalist and mineralogist.

As Regius Professor of Natural History at the Univers ...

, and in January 1819 began to study German, desiring to read the mineralogical works of Abraham Gottlob Werner. In February and March, he translated a piece by Jöns Jacob Berzelius, and by September he was "reading Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

". In November he enrolled in "the class of Scots law

Scots law () is the List of country legal systems, legal system of Scotland. It is a hybrid or mixed legal system containing Civil law (legal system), civil law and common law elements, that traces its roots to a number of different histori ...

", studying under David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

(the advocate). In December 1819 and January 1820, Carlyle made his second attempt at publishing, writing a review-article on Marc-Auguste Pictet's review of Jean-Alfred Gautier's ''Essai historique sur le problème des trois corps'' (1817) which went unpublished and is lost. The law classes ended in March 1820 and he did not pursue the subject any further.

In the same month, he wrote several articles for David Brewster

Sir David Brewster Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order, KH President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, PRSE Fellow of the Royal Society of London, FRS Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, FSA Scot Fellow of the Scottish Society of ...

's '' Edinburgh Encyclopædia'' (1808–1830), which appeared in October. These were his first published writings. In May and June, Carlyle wrote a review-article on the work of Christopher Hansteen, translated a book by Friedrich Mohs, and read Goethe's ''Faust''. By the autumn, Carlyle had also learned Italian and was reading Vittorio Alfieri, Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

and Sismondi, though German literature was still his foremost interest, having "revealed" to him a "new Heaven and new Earth". In March 1821, he finished two more articles for Brewster's encyclopedia, and in April he completed a review of Joanna Baillie's ''Metrical Legends'' (1821).

In May, Carlyle was introduced to Jane Baillie Welsh by Irving in Haddington. The two began a correspondence, and Carlyle sent books to her, encouraging her intellectual pursuits; she called him "my German Master".

"Conversion": Leith Walk and Hoddam Hill (1821–1826)

During this time, Carlyle struggled with what he described as "the dismallest Lernean Hydra of problems, spiritual, temporal, eternal". Spiritual doubt, lack of success in his endeavours, and dyspepsia were all damaging his physical and mental health, for which he found relief only in "sea-bathing". In early July 1821, "during those 3 weeks of total sleeplessness, in which almost" his "one solace was that of a daily bathe on the sands between nowiki/> Leith.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Leith">nowiki/>Leithand Portobello, Edinburgh">Portobello", an "incident" occurred in Leith Walk">Leith">nowiki/>Leith">Leith.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Leith">nowiki/>Leithand Portobello, Edinburgh">Portobello", an "incident" occurred in Leith Walk as he "went ''down''" into the water. This was the beginning of Carlyle's "Conversion", the process by which he "authentically took the Devil by the nose" and flung "''him'' behind me". It gave him courage in his battle against the "Hydra"; to his brother John, he wrote, "What is there to fear, indeed?" Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review">Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review'', and shortly afterwards began a tutorship for the distinguished Buller family, tutoring Charles Buller and his brother Arthur William Buller until July; he would work for the family until July 1824. Carlyle completed the Legendre translation in July 1822, having prefixed his own essay "On Proportionality (mathematics), Proportion", which Augustus De Morgan later called "as good a substitute for the fifth Book of Euclid as could have been given in that space".

Carlyle's translation of Goethe's ''

Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review">Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review'', and shortly afterwards began a tutorship for the distinguished Buller family, tutoring Charles Buller and his brother Arthur William Buller until July; he would work for the family until July 1824. Carlyle completed the Legendre translation in July 1822, having prefixed his own essay "On Proportionality (mathematics), Proportion", which Augustus De Morgan later called "as good a substitute for the fifth Book of Euclid as could have been given in that space".

Carlyle's translation of Goethe's ''Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship

''Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship'' () is the second novel by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, published in 1795–96.

Plot

The novel is in eight books. The main character Wilhelm Meister undergoes a journey of self-realization. The story centers ...

'' (1824) and '' Travels'' (1825) and his biography of Schiller (1825) brought him a decent income, which had before then eluded him, and he garnered a modest reputation. He began corresponding with Goethe and made his first trip to London in 1824, meeting with prominent writers such as Thomas Campbell, Charles Lamb, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

, and gaining friendships with Anna Montagu, Bryan Waller Proctor, and Henry Crabb Robinson. He also travelled to Paris in October–November with Edward Strachey and Kitty Kirkpatrick, where he attended Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

's introductory lecture on comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

, gathered information on the study of medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, introduced himself to Legendre, was introduced by Legendre to Charles Dupin

Baron Pierre Charles François Dupin (; 6 October 1784, Varzy, Nièvre – 18 January 1873, Paris, France) was a French Catholic mathematician, engineer, economist and politician, particularly known for work in the field of mathematics, where t ...

, observed Laplace and several other notables while declining offers of introduction by Dupin, and heard François Magendie read a paper on the " fifth pair of nerves".

In May 1825, Carlyle moved into a cottage farmhouse in Hoddam Hill near Ecclefechan, which his father had leased for him. Carlyle lived with his brother Alexander, who, "with a cheap little man-servant", worked on the farm, his mother with her one maid-servant, and his two youngest sisters, Jean and Jenny. He had constant contact with the rest of his family, most of whom lived close by at Mainhill, a farm owned by his father. Jane made a successful visit in September 1825. Whilst there, Carlyle wrote ''German Romance'' (1827), a translation of German novellas by Johann Karl August Musäus, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Ludwig Tieck

Johann Ludwig Tieck (; ; 31 May 177328 April 1853) was a German poet, fiction writer, translator, and critic. He was one of the founding fathers of the Romanticism, Romantic movement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Early life

Tieck w ...

, E. T. A. Hoffmann, and Jean Paul

Jean Paul (; born Johann Paul Friedrich Richter, 21 March 1763 – 14 November 1825) was a German Romanticism, German Romantic writer, best known for his humorous novels and stories.

Life and work

Jean Paul was born at Wunsiedel, in the Ficht ...

. In Hoddam Hill, Carlyle found respite from the "intolerable fret, noise and confusion" that he had experienced in Edinburgh, and observed what he described as "the finest and vastest prospect all round it I ever saw from any house", with "all Cumberland as in amphitheatre unmatchable". Here, he completed his "Conversion" which began with the Leith Walk incident. He achieved "a grand and ''ever''-joyful victory", in the "final chaining down, and trampling home, 'for good,' home into their caves forever, of all" his "''Spiritual Dragons''". By May 1826, problems with the landlord and the agreement forced the family's relocation to Scotsbrig, a farm near Ecclefechan. Later in life, he remembered the year at Hoddam Hill as "perhaps the most triumphantly important of my life."

Marriage, Comely Bank and Craigenputtock (1826–1834)

In October 1826, Thomas and Jane Welsh were married at the Welsh family farm in Templand. Shortly after their marriage, the Carlyles moved into a modesthome

A home, or domicile, is a space used as a permanent or semi-permanent residence for one or more human occupants, and sometimes various companion animals. Homes provide sheltered spaces, for instance rooms, where domestic activity can be p ...

on Comely Bank in Edinburgh, that had been leased for them by Jane's mother. They lived there from October 1826 to May 1828. In that time, Carlyle published ''German Romance'', began ''Wotton Reinfred'', an autobiographical novel which he left unfinished, and published his first article for the ''Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'', ...

'', "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter" (1827). "Richter" was the first of many essays extolling the virtues of German authors, who were then little-known to English readers; "State of German Literature" was published in October. In Edinburgh, Carlyle made contact with several distinguished literary figures, including ''Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'', ...

'' editor Francis Jeffrey, John Wilson of '' Blackwood's Magazine'', essayist Thomas De Quincey, and philosopher William Hamilton. In 1827 Carlyle attempted to land the Chair of Moral Philosophy at St. Andrews without success, despite support from an array of prominent intellectuals, including Goethe. He also made an unsuccessful attempt for a professorship at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a collegiate university, federal Public university, public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The ...

.

In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834. He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of Werner", "Goethe's Helena", "Goethe", "Robert Burns, Burns", "The Life of Heyne" (each 1828), "German Playwrights", "Voltaire", "Novalis" (each 1829), "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter Again" (1830), "Cruthers and Jonson; or The Outskirts of Life: A True Story", "Luther's Psalm", and "Schiller" (each 1831). He began but did not complete a history of German literature, from which he drew material for essays "The Nibelungen Lied", "Early German Literature" and parts of "Historic Survey of German Poetry" (each 1831). He published early thoughts on the philosophy of history in "Thoughts on History" (1830) and wrote his first pieces of social criticism, "Signs of the Times" (1829) and "Characteristics" (1831).D. Daiches (ed.), ''Companion to Literature 1'' (London, 1965), p. 89. "Signs" garnered the interest of Gustave d'Eichthal, a member of the Saint-Simonians, who sent Carlyle Saint-Simonian literature, including Henri de Saint-Simon's ''Nouveau Christianisme'' (1825), which Carlyle translated and wrote an introduction for.

In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to Craigenputtock, the main house of Jane's modest agricultural estate in Dumfriesshire, which they occupied until May 1834. He wrote a number of essays there which earned him money and augmented his reputation, including "Life and Writings of Werner", "Goethe's Helena", "Goethe", "Robert Burns, Burns", "The Life of Heyne" (each 1828), "German Playwrights", "Voltaire", "Novalis" (each 1829), "Jean Paul Friedrich Richter Again" (1830), "Cruthers and Jonson; or The Outskirts of Life: A True Story", "Luther's Psalm", and "Schiller" (each 1831). He began but did not complete a history of German literature, from which he drew material for essays "The Nibelungen Lied", "Early German Literature" and parts of "Historic Survey of German Poetry" (each 1831). He published early thoughts on the philosophy of history in "Thoughts on History" (1830) and wrote his first pieces of social criticism, "Signs of the Times" (1829) and "Characteristics" (1831).D. Daiches (ed.), ''Companion to Literature 1'' (London, 1965), p. 89. "Signs" garnered the interest of Gustave d'Eichthal, a member of the Saint-Simonians, who sent Carlyle Saint-Simonian literature, including Henri de Saint-Simon's ''Nouveau Christianisme'' (1825), which Carlyle translated and wrote an introduction for.

Most notably, he wrote ''

Most notably, he wrote ''Sartor Resartus

''Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books'' is a novel by the Scottish people, Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in ''Fraser's Magazine'' in November 1833 ...

''. Finishing the manuscript in late July 1831, Carlyle began his search for a publisher, leaving for London in early August. He and his wife lived there for the winter at 4 (now 33) Ampton Street, Kings Cross, in a house built by Thomas Cubitt. The death of Carlyle's father in January 1832 and his inability to attend the funeral moved him to write the first of what would become the ''Reminiscences'', published posthumously in 1881. Carlyle had not found a publisher by the time he returned to Craigenputtock in March but he had initiated important friendships with Leigh Hunt

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 178428 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Hunt co-founded '' The Examiner'', a leading intellectual journal expounding radical principles. He was the centre ...

and John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

. That year, Carlyle wrote the essays "Goethe's Portrait", "Death of Goethe", "Goethe's Works", "Biography", "Boswell's Life of Johnson", and "Corn-Law Rhymes". Three months after their return from a January to May 1833 stay in Edinburgh, the Carlyles were visited at Craigenputtock by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson (and other like-minded Americans) had been deeply affected by Carlyle's essays and determined to meet him during the northern terminus of a literary pilgrimage; it was to be the start of a lifelong friendship and a famous correspondence. 1833 saw the publication of the essays "Diderot" and "Count Cagliostro"; in the latter, Carlyle introduced the idea of " Captains of Industry".

Chelsea (1834–1845)

In June 1834, the Carlyles moved into 5 Cheyne Row, Chelsea, which became their home for the remainder of their respective lives. Residence in London wrought a large expansion of Carlyle's social circle. He became acquainted with scores of leading writers, novelists, artists, radicals, men of science, Church of England clergymen, and political figures. Two of his most important friendships were withLord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

and Lady Ashburton; though Carlyle's warm affection for the latter would eventually strain his marriage, the Ashburtons helped to broaden his social horizons, giving him access to circles of intelligence, political influence, and power.

Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in '' Fraser's Magazine'', with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory. That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the French Revolution and set about researching and writing it shortly thereafter. Having completed the first volume after five months of writing, he lent the manuscript to Mill, who had been supplying him with materials for his research. One evening in March 1835, Mill arrived at Carlyle's door appearing "unresponsive, pale, the very picture of despair". He had come to tell Carlyle that the manuscript was destroyed. It had been "left out", and Mill's housemaid took it for wastepaper, leaving only "some four tattered leaves". Carlyle was sympathetic: "I can be angry with no one; for they that were concerned in it have a far deeper sorrow than mine: it is purely the hand of Providence". The next day, Mill offered Carlyle , of which he would only accept £100. He began the volume anew shortly afterwards. Despite an initial struggle, he was not deterred, feeling like "a runner that tho' ''tripped'' down, will not lie there, but rise and run again." By September, the volume was rewritten. That year, he wrote a eulogy for his friend, "Death of Edward Irving".

In April 1836, with the intercession of Emerson, ''Sartor Resartus'' was first published in book form in Boston, soon selling out its initial run of five hundred copies. Carlyle's three-volume history of the French Revolution was completed in January 1837 and sent to the press. Contemporaneously, the essay "Memoirs of Mirabeau" was published, as was " The Diamond Necklace" in January and February, and "Parliamentary History of the French Revolution" in April. In need of further financial security, Carlyle began a series of lectures on German literature in May, delivered extemporaneously in Willis' Rooms. ''

Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in '' Fraser's Magazine'', with the instalments appearing between November 1833 and August 1834. Despite early recognition from Emerson, Mill and others, it was generally received poorly, if noticed at all. In 1834, Carlyle applied unsuccessfully for the astronomy professorship at the Edinburgh observatory. That autumn, he arranged for the publication of a history of the French Revolution and set about researching and writing it shortly thereafter. Having completed the first volume after five months of writing, he lent the manuscript to Mill, who had been supplying him with materials for his research. One evening in March 1835, Mill arrived at Carlyle's door appearing "unresponsive, pale, the very picture of despair". He had come to tell Carlyle that the manuscript was destroyed. It had been "left out", and Mill's housemaid took it for wastepaper, leaving only "some four tattered leaves". Carlyle was sympathetic: "I can be angry with no one; for they that were concerned in it have a far deeper sorrow than mine: it is purely the hand of Providence". The next day, Mill offered Carlyle , of which he would only accept £100. He began the volume anew shortly afterwards. Despite an initial struggle, he was not deterred, feeling like "a runner that tho' ''tripped'' down, will not lie there, but rise and run again." By September, the volume was rewritten. That year, he wrote a eulogy for his friend, "Death of Edward Irving".

In April 1836, with the intercession of Emerson, ''Sartor Resartus'' was first published in book form in Boston, soon selling out its initial run of five hundred copies. Carlyle's three-volume history of the French Revolution was completed in January 1837 and sent to the press. Contemporaneously, the essay "Memoirs of Mirabeau" was published, as was " The Diamond Necklace" in January and February, and "Parliamentary History of the French Revolution" in April. In need of further financial security, Carlyle began a series of lectures on German literature in May, delivered extemporaneously in Willis' Rooms. ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British political and cultural news magazine. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving magazine in the world. ''The Spectator'' is politically conservative, and its principal subject a ...

'' reported that the first lecture was given "to a very crowded and yet a select audience of both sexes." Carlyle recalled being "wasted and fretted to a thread, my tongue ... dry as charcoal: the people were there, I was obliged to stumble in, and start. ''Ach Gott!''" Despite his inexperience as a lecturer and deficiency "in the mere mechanism of oratory", reviews were positive and the series proved profitable for him.

During Carlyle's lecture series, '' The French Revolution: A History'' was officially published. It marked his career breakthrough. At the end of the year, Carlyle reported to Karl August Varnhagen von Ense that his earlier efforts to popularise German literature were beginning to produce results, and expressed his satisfaction: "''Deutschland'' will reclaim her great Colony; we shall become more ''Deutsch'', that is to say more ''English'', at same time." ''The French Revolution'' fostered the republication of ''Sartor Resartus'' in London in 1838 as well as a collection of his earlier writings in the form of the '' Critical and Miscellaneous Essays'', facilitated in Boston with the aid of Emerson. Carlyle presented his second lecture series in April and June 1838 on the history of literature at the Marylebone Institution in Portman Square. '' The Examiner'' reported that at the end of the second lecture, "Mr. Carlyle was heartily greeted with applause." Carlyle felt that they "went on better and better, and grew at last, or threatened to grow, quite a flaming affair." He published two essays in 1838, "Sir Walter Scott", being a review of John Gibson Lockhart's biography, and "Varnhagen von Ense's Memoirs". In April 1839, Carlyle published "Petition on the Copyright Bill". A third series of lectures was given in May on the revolutions of modern Europe, which the ''Examiner'' reviewed positively, noting after the third lecture that "Mr. Carlyle's audiences appear to increase in number every time." Carlyle wrote to his mother that the lectures were met "with very kind acceptance from people more distinguished than ever; yet still with a feeling that I was far from the ''right'' lecturing point yet." In July, he published "On the Sinking of the Vengeur" and in December he published ''Chartism'', a pamphlet in which he addressed the movement of the same name and raised the Condition-of-England question.

In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as '' On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History.'' Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of 'sic''with sufficient ''éclat;'' the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad ''best'' I have yet given." In the 1840 edition of the ''Essays'', Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833. Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh. Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841. He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books,

In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as '' On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History.'' Carlyle wrote to his brother John afterwards, "The Lecturing business went of 'sic''with sufficient ''éclat;'' the Course was generally judged, and I rather join therein myself, to be the bad ''best'' I have yet given." In the 1840 edition of the ''Essays'', Carlyle published "Fractions", a collection of poems written from 1823 to 1833. Later that year, he declined a proposal for a professorship of history at Edinburgh. Carlyle was the principal founder of the London Library in 1841. He had become frustrated by the facilities available at the British Museum Library, where he was often unable to find a seat (obliging him to perch on ladders), where he complained that the enforced close confinement with his fellow readers gave him a "museum headache", where the books were unavailable for loan, and where he found the library's collections of pamphlets and other material relating to the French Revolution and English Civil Wars inadequately catalogued. In particular, he developed an antipathy to the Keeper of Printed Books, Anthony Panizzi

Sir Antonio Genesio Maria Panizzi (16 September 1797 – 8 April 1879), better known as Anthony Panizzi, was a naturalised British citizen of Italian birth, and an Italian patriot. He was a librarian, becoming the Principal Librarian (i.e. hea ...

(despite the fact that Panizzi had allowed him many privileges not granted to other readers), and criticised him in a footnote to an article published in the ''Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly United Kingdom, British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the libe ...

'' as the "respectable Sub-Librarian". Carlyle's eventual solution, with the support of a number of influential friends, was to call for the establishment of a private subscription library

A subscription library (also membership library or independent library) is a library that is financed by private funds either from membership fees or endowments. Unlike a public library, access is often restricted to members, but access rights ca ...

from which books could be borrowed.

Carlyle had chosen Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

as the subject for a book in 1840 and struggled to find what form it would take. In the interim, he wrote '' Past and Present'' (1843) and the articles " Baillie the Covenanter" (1841), "Dr. Francia" (1843), and "An Election to the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an Parliament of England, English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660, making it the longest-lasting Parliament in English and British history. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened f ...

" (1844). Carlyle declined an offer for professorship from St. Andrews in 1844. The first edition of '' Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches: with Elucidations'' was published in 1845; it was a popular success and did much to revise Cromwell's standing in Britain.

Journeys to Ireland and Germany (1846–1865)

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy as a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland. Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in ''

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy as a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Irish question in 1848. These were "Ireland and the British Chief Governor", "Irish Regiments (of the New Æra)", and "The Repeal of the Union", each of which offered solutions to Ireland's problems and argued to preserve England's connection with Ireland. Carlyle wrote an article titled "Ireland and Sir Robert Peel" (signed "C.") published in April 1849 in ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British political and cultural news magazine. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving magazine in the world. ''The Spectator'' is politically conservative, and its principal subject a ...

'' in response to two speeches given by Peel wherein he made many of the same proposals which Carlyle had earlier suggested; he called the speeches "like a prophecy of better things, inexpressibly cheering." In May, he published "Indian Meal", in which he advanced maize

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native American ...

as a remedy to the Great Famine as well as the worries of "disconsolate Malthusians". He visited Ireland again with Duffy later that year while recording his impressions in his letters and a series of memoranda, published as ''Reminiscences of My Irish Journey in 1849'' after his death; Duffy would publish his own memoir of their travels, ''Conversations with Carlyle''.

Carlyle's travels in Ireland deeply affected his views on society, as did the Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

. While embracing the latter as necessary in order to cleanse society of various forms of anarchy and misgovernment, he denounced their democratic undercurrent and insisted on the need for authoritarian leaders. These events inspired his next two works, " Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" (1849), in which he coined the term " Dismal Science" to describe political economy, and '' Latter-Day Pamphlets'' (1850). The illiberal content of these works sullied Carlyle's reputation for some progressives, while endearing him to those that shared his views. In 1851, Carlyle wrote '' The Life of John Sterling'' as a corrective to Julius Hare's unsatisfactory 1848 biography. In late September and early October, he made his second trip to Paris, where he met Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( ; ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian who served as President of France from 1871 to 1873. He was the second elected president and the first of the Third French Republic.

Thi ...

and Prosper Mérimée; his account, "Excursion (Futile Enough) to Paris; Autumn 1851", was published posthumously.

In 1852, Carlyle began research on Frederick the Great, whom he had expressed interest in writing a biography of as early as 1830. He travelled to Germany that year, examining source documents and prior histories. Carlyle struggled through research and writing, telling von Ense it was "the poorest, most troublesome and arduous piece of work he has ever undertaken". In 1856, the first two volumes of '' History of Friedrich II. of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great'' were sent to the press and published in 1858. During this time, he wrote "The Opera" (1852), "Project of a National Exhibition of Scottish Portraits" (1854) at the request of David Laing, and "The Prinzenraub" (1855). In October 1855, he finished ''The Guises'', a history of the House of Guise and its relation to Scottish history, which was first published in 1981. Carlyle made a second expedition to Germany in 1858 to survey the topography of battlefields, which he documented in ''Journey to Germany, Autumn 1858'', published posthumously. In May 1863, Carlyle wrote the short dialogue "Ilias (Americana) in Nuce" (American Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

in a Nutshell) on the topic of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. Upon publication in August, the "Ilias" drew scornful letters from David Atwood Wasson and Horace Howard Furness. In the summer of 1864, Carlyle lived at 117 Marina (built by James Burton) in St Leonards-on-Sea, in order to be nearer to his ailing wife who was in possession of caretakers there.

Carlyle planned to write four volumes but had written six by the time ''Frederick'' was finished in 1865. Before its end, Carlyle had developed a tremor in his writing hand. Upon its completion, it was received as a masterpiece. He earned a sobriquet, the " Sage of Chelsea", and in the eyes of those that had rebuked his politics, it restored Carlyle to his position as a great man of letters. Carlyle was elected Lord Rector of Edinburgh University in November 1865, succeeding William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

and defeating Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

by a vote of 657 to 310.

Final years (1866–1881)

Carlyle travelled to Scotland to deliver his "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" as Rector in April 1866. During his trip, he was accompanied by John Tyndall, Thomas Henry Huxley, and Thomas Erskine. One of those that welcomed Carlyle on his arrival was Sir David Brewster, Principal of the university and the commissioner of Carlyle's first professional writings for the ''Edinburgh Encyclopædia''. Carlyle was joined onstage by his fellow travellers, Brewster, Moncure D. Conway, George Harvey, Lord Neaves, and others. Carlyle spoke extemporaneously on several subjects, concluding his address with a quote from Goethe: "Work, and despair not: ''Wir heissen euch hoffen,'' 'We bid you be of hope!'" Tyndall reported to Jane in a three-word telegram that it was "A perfect triumph." The warm reception he received in his homeland of Scotland marked the climax of Carlyle's life as a writer. While still in Scotland, Carlyle received abrupt news of Jane's sudden death in London. Upon her death, Carlyle began to edit his wife's letters and write reminiscences of her. He experienced feelings of guilt as he read her complaints about her illnesses, his friendship with Lady Harriet Ashburton, and his devotion to his labour, particularly on ''Frederick the Great''. Although deep in grief, Carlyle remained active in public life. Amidst controversy over governor John Eyre's violent repression of the Morant Bay rebellion, Carlyle assumed leadership of the Eyre Defence and Aid Fund in 1865 and 1866. The Defence had convened in response to the anti-Eyre Jamaica Committee, led by Mill and backed byCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

, and others. Carlyle and the Defence were supported by John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

, and Charles Kingsley.D. Daiches ed., ''Companion to Literature 1'' (London, 1965), p. 90. From December 1866 to March 1867, Carlyle resided at the home of Louisa Baring, Lady Ashburton in Menton

Menton (; in classical norm or in Mistralian norm, , ; ; or depending on the orthography) is a Commune in France, commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italia ...

, where he wrote reminiscences of Irving, Jeffrey, Robert Southey, and William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poetry, Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romanticism, Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Balla ...

. In August, he published "Shooting Niagara: And After?", an essay in response and opposition to the Second Reform Bill. In 1868, he wrote reminiscences of John Wilson and William Hamilton, and his niece Mary Aitken Carlyle moved into 5 Cheyne Row, becoming his caretaker and assisting in the editing of Jane's letters. In March 1869, he met with Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

, who wrote in her journal of "Mr. Carlyle, the historian, a strange-looking eccentric old Scotchman, who holds forth, in a drawling melancholy voice, with a broad Scotch accent, upon Scotland and upon the utter degeneration of everything." In 1870, he was elected president of the London Library, and in November he wrote a letter to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' in support of Germany in the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

. His conversation was recorded by a number of friends and visitors in later years, most notably William Allingham, who became known as Carlyle's Boswell.

In the spring of 1874, Carlyle accepted the '' Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste'' from Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

and declined Disraeli's offers of a state pension and the Knight Grand Cross in the Order of the Bath in the autumn. On the occasion of his eightieth birthday in 1875, he was presented with a commemorative medal crafted by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm and an address of admiration signed by 119 of the leading writers, scientists, and public figures of the day. "Early Kings of Norway", a recounting of historical material from the Icelandic sagas transcribed by Mary acting as his amanuensis, and an essay on "The Portraits of John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

" (both 1875) were his last major writings to be published in his lifetime. In November 1876, he wrote a letter in the ''Times'' "On the Eastern Question", entreating England not to enter the Russo-Turkish War on the side of the Turks. Another letter to the ''Times'' in May 1877 "On the Crisis", urging against the rumoured wish of Disraeli's to send a fleet to the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

and warning not to provoke Russia and Europe at large into a war against England, marked his last public utterance. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

elected him a Foreign Honorary Member in 1878.

On 2 February 1881, Carlyle fell into a coma. For a moment he awakened, and Mary heard him speak his final words: "So this is Death—well ..." He thereafter lost his speech and died on the morning of 5 February. An offer of interment at Westminster Abbey, which he had anticipated, was declined by his executors in accordance with his will. He was laid to rest with his mother and father in Hoddam Kirkyard in Ecclefechan, according to old Scottish custom. His private funeral, held on 10 February, was attended by family and a few friends, including Froude, Conway, Tyndall, and William Lecky, as local residents looked on.

Works

Carlyle's corpus spans the genres of "criticism, biography, history, politics, poetry, and religion." His innovative writing style, known as Carlylese, greatly influenced Victorian literature and anticipated techniques of postmodern literature. In his philosophy, while not adhering to any formal religion, Carlyle asserted the importance of belief during an age of increasing doubt. Much of his work is concerned with the modern human spiritual condition; he was the first writer to use the expression " meaning of life". In ''Sartor Resartus

''Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books'' is a novel by the Scottish people, Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in ''Fraser's Magazine'' in November 1833 ...

'' and in his early '' Miscellanies'', he developed his own philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known Text (literary theo ...

based upon what he called " Natural Supernaturalism", the idea that all things are "Clothes" which at once reveal and conceal the divine, that "a mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one", and that duty, work and silence are essential.

Carlyle postulated the Great Man theory