The Kingdom of Pontus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pontus ( grc-gre, Πόντος ) was a

The Kingdom of Pontus was divided into two distinct areas: the coastal region and the Pontic interior. The coastal region bordering the Black Sea was separated from the mountainous inland area by the

The Kingdom of Pontus was divided into two distinct areas: the coastal region and the Pontic interior. The coastal region bordering the Black Sea was separated from the mountainous inland area by the  The division between coast and interior was also cultural. The coast was mainly Greek and focused on sea trade. The interior was occupied by the Anatolian Cappadocians and Paphlagonians ruled by an Iranian aristocracy that went back to the Persian empire. The interior also had powerful temples with large estates. The gods of the Kingdom were mostly syncretic, with features of local gods along with Persian and Greek deities. Major gods included the Persian

The division between coast and interior was also cultural. The coast was mainly Greek and focused on sea trade. The interior was occupied by the Anatolian Cappadocians and Paphlagonians ruled by an Iranian aristocracy that went back to the Persian empire. The interior also had powerful temples with large estates. The gods of the Kingdom were mostly syncretic, with features of local gods along with Persian and Greek deities. Major gods included the Persian

Mithridates VI Eupator, 'the Good Father', followed a decisive anti-Roman agenda, extolling Greek and Iranian culture against ever-expanding Roman influence. Rome had recently created the province of Asia in Anatolia, and it had also rescinded the region of Phrygia Major from Pontus during the reign of Laodice. Mithridates began his expansion by inheriting

Mithridates VI Eupator, 'the Good Father', followed a decisive anti-Roman agenda, extolling Greek and Iranian culture against ever-expanding Roman influence. Rome had recently created the province of Asia in Anatolia, and it had also rescinded the region of Phrygia Major from Pontus during the reign of Laodice. Mithridates began his expansion by inheriting

Sulla now headed north, seeking the fertile plains of Boeotia to supply his army. At the Battle of Chaeronea, Sulla inflicted severe casualties on Archelaus, who nevertheless retreated and continued to raid Greece with the Pontic fleet. Archelaus regrouped and attacked a second time at the

Sulla now headed north, seeking the fertile plains of Boeotia to supply his army. At the Battle of Chaeronea, Sulla inflicted severe casualties on Archelaus, who nevertheless retreated and continued to raid Greece with the Pontic fleet. Archelaus regrouped and attacked a second time at the

/ref> Like many

Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

kingdom centered in the historical region of Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

and ruled by the Mithridatic dynasty

The Mithridatic dynasty, also known as the Pontic dynasty, was a hereditary dynasty of Persian origin, founded by Mithridates I Ktistes (''Mithridates III of Cius'') in 281 BC. The origins of the dynasty were located in the highest circles of t ...

(of Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

origin), which possibly may have been directly related to Darius the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty. The kingdom was proclaimed by Mithridates I in 281BC and lasted until its conquest by the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

in 63BC. The Kingdom of Pontus reached its largest extent under Mithridates VI

Mithridates or Mithradates VI Eupator ( grc-gre, Μιθραδάτης; 135–63 BC) was ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus in northern Anatolia from 120 to 63 BC, and one of the Roman Republic's most formidable and determined opponents. He was an e ...

the Great, who conquered Colchis

In Greco-Roman geography, Colchis (; ) was an exonym for the Georgian polity of Egrisi ( ka, ეგრისი) located on the coast of the Black Sea, centered in present-day western Georgia.

Its population, the Colchians are generally though ...

, Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Re ...

, Bithynia, the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

colonies of the Tauric Chersonesos, and for a brief time the Roman province of Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

. After a long struggle with Rome in the Mithridatic Wars

The Mithridatic Wars were three conflicts fought by Rome against the Kingdom of Pontus and its allies between 88 BC and 63 BC. They are named after Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus who initiated the hostilities after annexing the Roman provi ...

, Pontus was defeated. The western part of it was incorporated into the Roman Republic as the province Bithynia et Pontus

Bithynia and Pontus ( la, Provincia Bithynia et Pontus, Ancient Greek ) was the name of a province of the Roman Empire on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). It was formed during the late Roman Republic by the amalgamation o ...

; the eastern half survived as a client kingdom until 62 AD.

As the greater part of the kingdom lay within the region of Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Re ...

, which in early ages extended from the borders of Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

to the Euxine (Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

), the kingdom as a whole was at first called 'Cappadocia by Pontus' or 'Cappadocia by the Euxine', but afterwards simply 'Pontus', the name Cappadocia henceforth being used to refer to the southern half of the region previously included under that name.

The kingdom had three cultural strands which often fused together: Greek (mostly on the coast), Persian and Anatolian, with Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

becoming the official language in the 3rd century BC.

Features of Pontus

The Kingdom of Pontus was divided into two distinct areas: the coastal region and the Pontic interior. The coastal region bordering the Black Sea was separated from the mountainous inland area by the

The Kingdom of Pontus was divided into two distinct areas: the coastal region and the Pontic interior. The coastal region bordering the Black Sea was separated from the mountainous inland area by the Pontic Alps

The Pontic Mountains or Pontic Alps ( Turkish: ''Kuzey Anadolu Dağları'', meaning North Anatolian Mountains) form a mountain range in northern Anatolia, Turkey. They are also known as the ''Parhar Mountains'' in the local Turkish and Pontic Gr ...

, which run parallel to the coast. The river valleys of Pontus also ran parallel to the coast and were quite fertile, supporting cattle herds, millet, and fruit trees, including cherry, apple

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus domestica''). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus ''Malus''. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancestor, ' ...

, and pear

Pears are fruits produced and consumed around the world, growing on a tree and harvested in the Northern Hemisphere in late summer into October. The pear tree and shrub are a species of genus ''Pyrus'' , in the family Rosaceae, bearing the po ...

. (''Cherry'' and '' Cerasus'' are probably cognates.) The coastal region was dominated by Greek cities such as Amastris and Sinope, which became the Pontic capital after its capture. The coast was rich in timber, fishing, and olives. Pontus was also rich in iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

and silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

, which were mined near the coast south of Pharnacia

''Pharnacia''Stål C (1877) ''Öfversigt af Kongliga Vetenskaps-Akademiens Förhandlingar'' 34 (10): 40. is a tropical Asian genus of stick insects in the family Phasmatidae and subfamily Clitumninae (tribe Pharnaciini).

Species

The Catalogue ...

; steel from the Chalybian mountains became quite famous in Greece. There were also copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

and arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, ...

. The Pontic interior also had fertile river valleys such as the river Lycus and Iris. The major city of the interior was Amasia Amasia may refer to the following places:

* Amasya, a city in Northern Turkey

** Amasya Province, which contains the city

** Amasea (titular see), the former Metropolitan Archbishopric with see there, now a Latin Catholic titular see

* Amasia, Sh ...

, the early Pontic capital, where the Pontic kings had their palace and royal tombs. Besides Amasia Amasia may refer to the following places:

* Amasya, a city in Northern Turkey

** Amasya Province, which contains the city

** Amasea (titular see), the former Metropolitan Archbishopric with see there, now a Latin Catholic titular see

* Amasia, Sh ...

and a few other cities, the interior was dominated mainly by small villages. The kingdom of Pontus was divided into districts named Eparchies.Crook, Lintott & Rawson, ''The Cambridge Ancient History. Volume IX. The Last Age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 B.C.'', p. 133–136.

The division between coast and interior was also cultural. The coast was mainly Greek and focused on sea trade. The interior was occupied by the Anatolian Cappadocians and Paphlagonians ruled by an Iranian aristocracy that went back to the Persian empire. The interior also had powerful temples with large estates. The gods of the Kingdom were mostly syncretic, with features of local gods along with Persian and Greek deities. Major gods included the Persian

The division between coast and interior was also cultural. The coast was mainly Greek and focused on sea trade. The interior was occupied by the Anatolian Cappadocians and Paphlagonians ruled by an Iranian aristocracy that went back to the Persian empire. The interior also had powerful temples with large estates. The gods of the Kingdom were mostly syncretic, with features of local gods along with Persian and Greek deities. Major gods included the Persian Ahuramazda

Ahura Mazda (; ae, , translit=Ahura Mazdā; ), also known as Oromasdes, Ohrmazd, Ahuramazda, Hoormazd, Hormazd, Hormaz and Hurmuz, is the creator deity in Zoroastrianism. He is the first and most frequently invoked spirit in the ''Yasna''. ...

, who was termed Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label= genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label= genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek reli ...

Stratios; the moon god Men

A man is an adult male human. Prior to adulthood, a male human is referred to as a boy (a male child or adolescent). Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chro ...

Pharnacou; and Ma (interpreted as Cybele).

Sun gods were particularly popular, with the royal house being identified with the Persian god Ahuramazda of the Achaemenid dynasty; both Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

and Mithras

Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras. Although inspired by Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (''yazata'') Mithra, the Roman Mithras is link ...

were worshipped by the Kings. Indeed, the name used by the majority of the Pontic kings was Mithridates, which means "given by Mithras". Pontic culture represented a synthesis between Iranian, Anatolian and Greek elements, with the former two mostly associated with the interior parts, and the latter more so with the coastal region. By the time of MithridatesVI Eupator, Greek was the official language of the Kingdom, though Anatolian languages continued to be spoken in the interior.B. C. McGing, ''The foreign policy of Mithridates VI Eupator, King of Pontus'', p. 10–11.

History

Mithridatic Dynasty of Cius

The region of Pontus was originally part of the Persian satrapy ofCappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Re ...

(Katpatuka). The Persian dynasty which was to found this kingdom had, during the 4th century BC, ruled the Greek city of Cius

Cius (; grc-gre, Kίος or Κῖος ''Kios''), later renamed Prusias on the Sea (; la, Prusias ad Mare) after king Prusias I of Bithynia, was an ancient Greek city bordering the Propontis (now known as the Sea of Marmara), in Bithynia and i ...

(or Kios) in Mysia

Mysia (UK , US or ; el, Μυσία; lat, Mysia; tr, Misya) was a region in the northwest of ancient Asia Minor (Anatolia, Asian part of modern Turkey). It was located on the south coast of the Sea of Marmara. It was bounded by Bithynia on th ...

, with its first known member being Mithridates of Cius. His son AriobarzanesII became satrap of Phrygia. He became a strong ally of Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

and revolted against Artaxerxes, but was betrayed by his son Mithridates II of Cius Mithridates of Cius (in Greek Mιθριδάτης or Mιθραδάτης; lived c. 386–302 BCE, ruled 337–302 BCE) a Persian noble, succeeded his kinsman or father Ariobarzanes II in 337 BCE as ruler of the Greek town of Cius in Mysia ...

.Xenophon "Cyropaedia", VIII 8.4 MithridatesII remained as ruler after Alexander's conquests and was a vassal to Antigonus I Monophthalmus, who briefly ruled Asia Minor after the Partition of Triparadisus

The Partition of Triparadisus was a power-sharing agreement passed at Triparadisus in 321 BC between the generals (''Diadochi'') of Alexander the Great, in which they named a new regent and arranged the repartition of the satrapies of Alexander's e ...

. Mithridates was killed by Antigonus in 302BC under suspicion that he was working with his enemy Cassander

Cassander ( el, Κάσσανδρος ; c. 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and ''de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a conte ...

. Antigonus planned to kill Mithridates' son, also called Mithridates (later named Ktistes, 'founder') but DemetriusI warned him and he escaped to the east with six horsemen.Appian "the Mithridatic wars", II Mithridates first went to the city of Cimiata in Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia (; el, Παφλαγονία, Paphlagonía, modern translit. ''Paflagonía''; tr, Paflagonya) was an ancient region on the Black Sea coast of north-central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus (region), Pontus t ...

and later to Amasya

Amasya () is a city in northern Turkey and is the capital of Amasya Province, in the Black Sea Region. It was called Amaseia or Amasia in antiquity."Amasya" in ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th ...

in Cappadocia. He ruled from 302 to 266BC, fought against Seleucus I

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the pow ...

and, in 281 (or 280) BC, declared himself king ('' basileus'') of a state in northern Cappadocia and eastern Paphlagonia. He further expanded his kingdom to the river Sangrius in the west. His son Ariobarzanes captured Amastris in 279, its first important Black sea port. Mithridates also allied with the newly arrived Galatians and defeated a force sent against him by Ptolemy I. Ptolemy had been expanding his territory in Asia Minor since the beginning of the First Syrian war against Antiochus in the mid-270s and was allied with Mithridates' enemy, Heraclea Pontica

__NOTOC__

Heraclea Pontica (; gr, Ἡράκλεια Ποντική, Hērakleia Pontikē), known in Byzantine and later times as Pontoheraclea ( gr, Ποντοηράκλεια, Pontohērakleia), was an ancient city on the coast of Bithynia in Asi ...

.

Kingdom of Pontus

We know little of Ariobarzanes' short reign, except that when he died his son MithridatesII (c.250—189) became king and was attacked by the Galatians. MithridatesII received aid fromHeraclea Pontica

__NOTOC__

Heraclea Pontica (; gr, Ἡράκλεια Ποντική, Hērakleia Pontikē), known in Byzantine and later times as Pontoheraclea ( gr, Ποντοηράκλεια, Pontohērakleia), was an ancient city on the coast of Bithynia in Asi ...

, who was also at war with the Galatians at this time. Mithridates went on to support Antiochus Hierax against his brother SeleucusII Callinicus. Seleucus was defeated in Anatolia by Hierax, Mithridates, and the Galatians. Mithridates also attacked Sinope in 220 but failed to take the city. He married SeleucusII's sister and gave his daughter in marriage to AntiochusIII, to obtain recognition for his new kingdom and create strong ties with the Seleucid Empire. The sources are silent on Pontus for the years following the death of MithridatesII, when his son MithridatesIII ruled (c.220–198/88).

Pharnaces I of Pontus

Pharnaces I ( el, Φαρνάκης; lived 2nd century BC), fifth king of Pontus, was of Persian and Greek ancestry. He was the son of King Mithridates III of Pontus and his wife Laodice, whom he succeeded on the throne. Pharnaces had two sibli ...

(189–159 BC) was much more successful in his expansion of the kingdom at the expense of the Greek coastal cities. He joined in a war with Prusias I of Bithynia

Prusias I Cholus (Greek: Προυσίας ὁ Χωλός "the Lame"; c. 243 – 182 BC) was a king of Bithynia, who reigned from c. 228 to 182 BC.

Life and Reign

Prusias was a vigorous and energetic leader; he fought a war against Byzantium ...

against Eumenes of Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on th ...

in 188 BC, but the two made peace in 183 after Bithynia suffered a series of reversals. He took Sinope in 182BC and although the Rhodians complained to Rome about this, nothing was done. Pharnaces also took the coastal cities of Cotyora

Ordu () or Altınordu is a port city on the Black Sea coast of Turkey, historically also known as Cotyora or Kotyora ( pnt, Κοτύωρα), and the capital of Ordu Province with a population of 229,214 in the city center.

Name

Kotyora, the ori ...

, Pharnacia

''Pharnacia''Stål C (1877) ''Öfversigt af Kongliga Vetenskaps-Akademiens Förhandlingar'' 34 (10): 40. is a tropical Asian genus of stick insects in the family Phasmatidae and subfamily Clitumninae (tribe Pharnaciini).

Species

The Catalogue ...

, and Trapezus

Trabzon (; Ancient Greek: Tραπεζοῦς (''Trapezous''), Ophitic Pontic Greek: Τραπεζούντα (''Trapezounta''); Georgian: ტრაპიზონი (''Trapizoni'')), historically known as Trebizond in English, is a city on the B ...

in the east, effectively gaining control of most of the northern Anatolian coastline. Despite Roman attempts to keep the peace, Pharnaces fought against Eumenes of Pergamon and Ariarathes of Cappadocia. While initially successful, it seems he was overmatched by 179 when he was forced to sign a treaty. He had to give up all lands he had obtained in Galatia, and Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia (; el, Παφλαγονία, Paphlagonía, modern translit. ''Paflagonía''; tr, Paflagonya) was an ancient region on the Black Sea coast of north-central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus (region), Pontus t ...

and the city of Tium, but he kept Sinope.Polybius "Histories", XXIV. 1, 5, 8, 9 XXV. 2 Seeking to extend his influence to the north, Pharnaces allied with the cities in the Chersonesus

Chersonesus ( grc, Χερσόνησος, Khersónēsos; la, Chersonesus; modern Russian and Ukrainian: Херсоне́с, ''Khersones''; also rendered as ''Chersonese'', ''Chersonesos'', contracted in medieval Greek to Cherson Χερσών; ...

and with other Black Sea cities such as Odessus

Varna ( bg, Варна, ) is the third-largest city in Bulgaria and the largest city and seaside resort on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast and in the Northern Bulgaria region. Situated strategically in the Gulf of Varna, the city has been a m ...

on the Bulgarian coast. Pharnaces' brother, MithridatesIV Philopator Philadelphus adopted a peaceful, pro-Roman policy. He sent aid to the Roman ally Attalus II Philadelphus

Attalus II Philadelphus (Greek: Ἄτταλος Β΄ ὁ Φιλάδελφος, ''Attalos II Philadelphos'', which means "Attalus the brother-loving"; 220–138 BC) was a Greek King of Pergamon and the founder of the city of Attalia (Antalya) ...

of Pergamon against Prusias II of Bithynia

Prusias II Cynegus (Greek: Προυσίας ὁ Κυνηγός; "the Hunter", c. 220 BC – 149 BC, reigned c. 182 BC – 149 BC) was the Greek king of Bithynia. He was the son and successor of Prusias I and Apama III.

Life

Prusias was ...

in 155.

His successor, Mithridates V of Pontus

Mithridates or Mithradates V Euergetes ( grc-gre, Μιθριδάτης ὁ εὐεργέτης, which means "Mithridates the benefactor"; fl. 2nd century BC, r. 150–120 BC) was a prince and the seventh king of the wealthy Kingdom of Pontus.

Mi ...

Euergetes, remained a friend of Rome and in 149 BC sent ships and a small force of auxiliaries to aid Rome in the third Punic War. He also sent troops for the war against Eumenes III

Eumenes III (; grc-gre, Εὐμένης Γʹ; originally named Aristonicus; in Greek Aristonikos Ἀριστόνικος) was a pretender to the throne of Pergamon. He led the against the Pergamene regime and found success early on, seizing vari ...

(Aristonicus), who had usurped the Pergamene throne after the death of Attalus III

Attalus III ( el, Ἄτταλος Γ΄) Philometor Euergetes ( – 133 BC) was the last Attalid king of Pergamon, ruling from 138 BC to 133 BC.

Biography

Attalus III was the son of king Eumenes II and his queen Stratonice of Pergamon, and ...

. After Rome received the Kingdom of Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on th ...

in the will of AttalusIII in the absence of an heir, they turned part of it into the province of Asia, while giving the rest to loyal allied kings. For his loyalty Mithridates was awarded the region of Phrygia Major. The kingdom of Cappadocia received Lycaonia

Lycaonia (; el, Λυκαονία, ''Lykaonia''; tr, Likaonya) was a large region in the interior of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), north of the Taurus Mountains. It was bounded on the east by Cappadocia, on the north by Galatia, on the west by ...

. Because of this it seems reasonable to assume that Pontus had some degree of control over Galatia, since Phrygia does not border Pontus directly. It is possible that Mithridates inherited part of Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia (; el, Παφλαγονία, Paphlagonía, modern translit. ''Paflagonía''; tr, Paflagonya) was an ancient region on the Black Sea coast of north-central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus (region), Pontus t ...

after the death of its King, Pylaemenes. MithridatesV married his daughter Laodice to the king of Cappadocia, Ariarathes VI of Cappadocia

Ariarathes VI Epiphanes Philopator ( grc, Ἀριαράθης Ἐπιφανής Φιλοπάτωρ), was the Ariarathid king of Cappadocia from 130 BC to 116 BC. He was the youngest son of Ariarathes V of Cappadocia and Nysa of Cappadocia.

Name ...

, and he also went on to invade Cappadocia, though the details of this war are unknown. Hellenization continued under MithridatesV. He was the first king to widely recruit Greek mercenaries in the Aegean, he was honored at Delos, and he depicted himself as Apollo on his coins. Mithridates was assassinated at Sinope in 121/0, the details of which are unclear.

Because both the sons of Mithridates V, MithridatesVI and Mithridates Chrestus Mithridates Chrestus ( el, Μιθριδάτης ό Χρηστός; ''the Good'', flourished 2nd century BC, died 115 BC-113 BC) was a Prince and co-ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus.

Chrestus was of Greek and Persian ancestry. He was the second son ...

, were still children, Pontus now came under the regency of his wife Laodice. She favored Chrestus, and MithridatesVI escaped the Pontic court. Legend would later say this was the time he traveled through Asia Minor, building his resistance to poisons and learning all of the languages of his subjects. He returned in 113BC to depose his mother; she was thrown into prison, and he eventually had his brother killed.

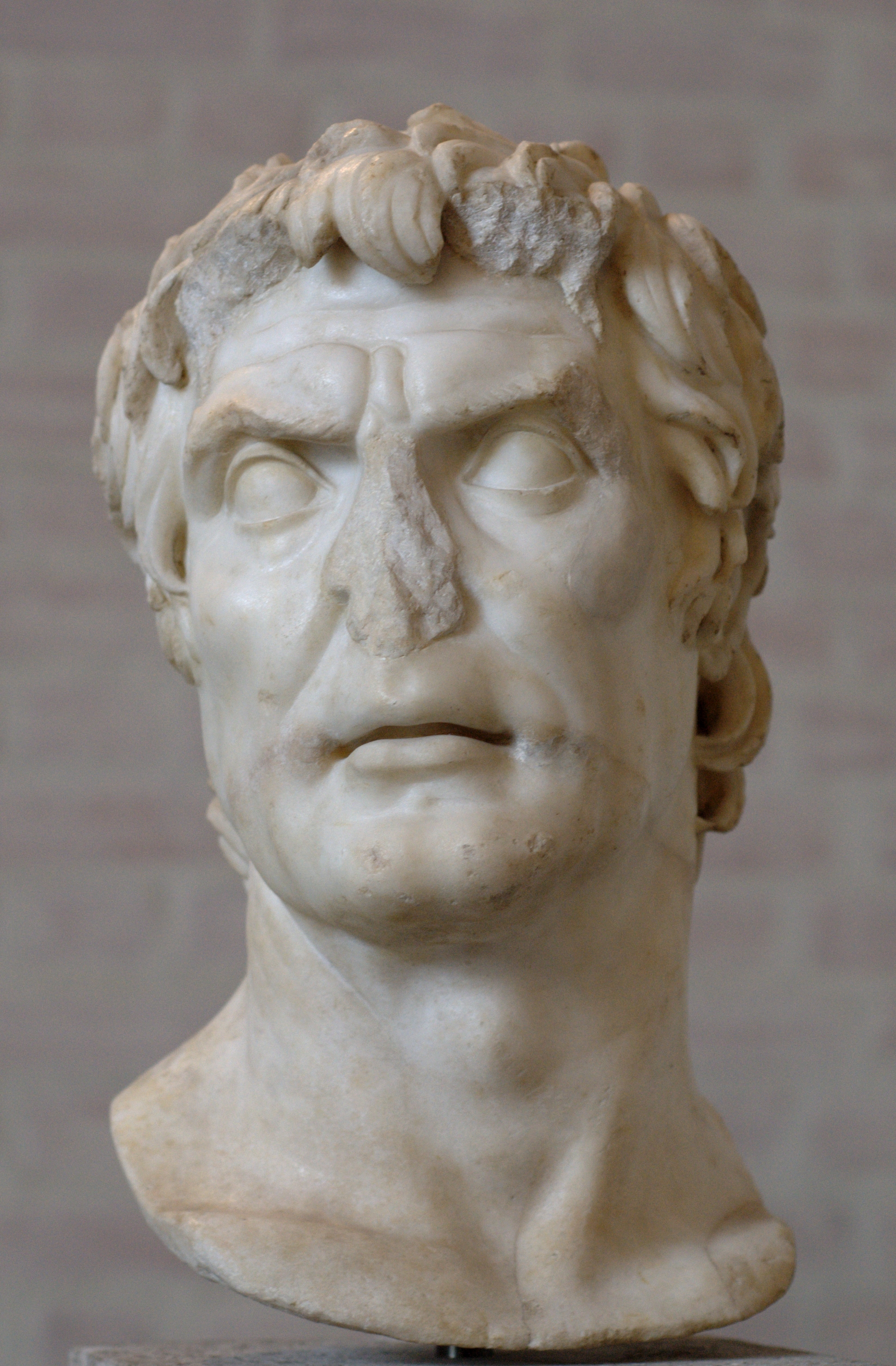

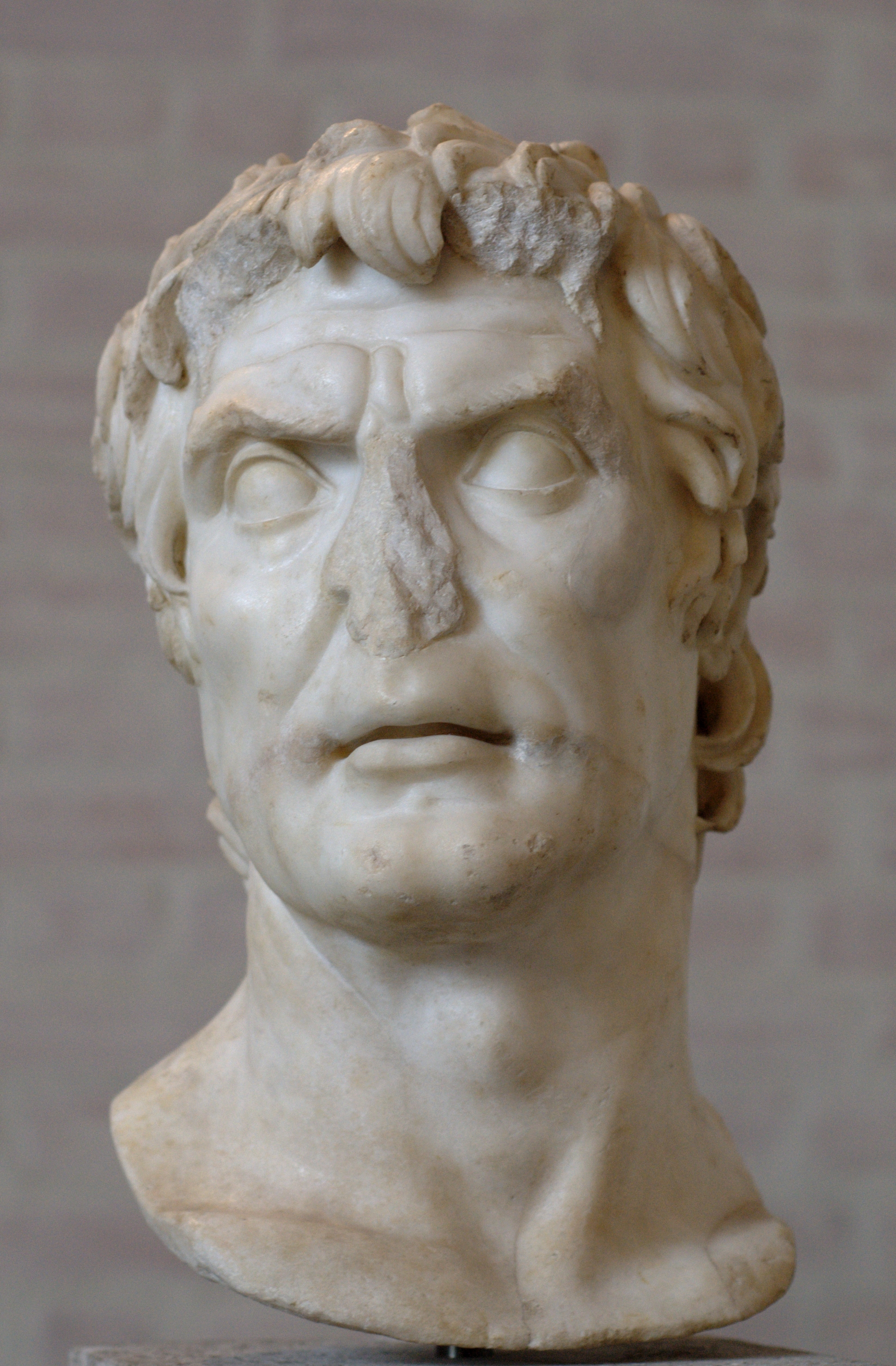

Mithridates VI Eupator

Mithridates VI Eupator, 'the Good Father', followed a decisive anti-Roman agenda, extolling Greek and Iranian culture against ever-expanding Roman influence. Rome had recently created the province of Asia in Anatolia, and it had also rescinded the region of Phrygia Major from Pontus during the reign of Laodice. Mithridates began his expansion by inheriting

Mithridates VI Eupator, 'the Good Father', followed a decisive anti-Roman agenda, extolling Greek and Iranian culture against ever-expanding Roman influence. Rome had recently created the province of Asia in Anatolia, and it had also rescinded the region of Phrygia Major from Pontus during the reign of Laodice. Mithridates began his expansion by inheriting Lesser Armenia

Lesser Armenia ( hy, Փոքր Հայք, ''Pokr Hayk''; la, Armenia Minor, Greek: Mikre Armenia, Μικρή Αρμενία), also known as Armenia Minor and Armenia Inferior, comprised the Armenian–populated regions primarily to the west and n ...

from King Antipater (precise date unknown, c.115–106) and by conquering the Kingdom of Colchis

In Greco-Roman geography, Colchis (; ) was an exonym for the Georgian polity of Egrisi ( ka, ეგრისი) located on the coast of the Black Sea, centered in present-day western Georgia.

Its population, the Colchians are generally though ...

. Colchis was an important region in Black Sea traderich with gold, wax, hemp, and honey. The cities of the Tauric Chersonesus

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' ( gr, Ταυρική or Ταυρικά), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' ( gr, Χερσόνησος Ταυρική, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the ...

now appealed for his aid against the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

in the north. Mithridates sent 6,000 men under General Diophantus. After various campaigns in the north of the Crimea he controlled all of the Chersonesus. Mithridates also developed trade links with cities on the western Black Sea coast.

At the time, Rome was fighting the Jugurthine and Cimbric wars. Mithridates and Nicomedes of Bithynia both invaded Paphlagonia and divided it amongst themselves. A Roman embassy was sent, but it accomplished nothing. Mithridates also took a part of Galatia that had previously been part of his father's kingdom and intervened in Cappadocia, where his sister Laodice was queen. In 116 the king of Cappadocia, AriarathesVI, was murdered by the Cappadocian noble Gordius at the behest of Mithridates, and Laodice ruled as regent over the sons of Ariarathes until 102BC. After Nicomedes III of Bithynia

Nicomedes III Euergetes ("the Benefactor", grc-gre, Νικομήδης Εὐεργέτης) was the king of Bithynia, from c. 127 BC to c. 94 BC. He was the son and successor of Nicomedes II of Bithynia.

Life

Memnon of Heraclea wrote that Nic ...

married Laodice, he tried to intervene in the region by sending troops; Mithridates swiftly invaded, placing his nephew Ariarathes VII of Cappadocia on the throne of Cappadocia. War soon broke out between the two, and Mithridates invaded with a large Pontic army, but AriarathesVII was murdered in 101BC before any battle was fought. Mithridates then installed his eight-year-old son, Ariarathes IX of Cappadocia

Ariarathes IX Eusebes Philopator ( grc, Ἀριαράθης Εὐσεβής Φιλοπάτωρ, Ariaráthēs Eusebḗs Philopátōr; reigned c. 100–85 BC), was made king of Cappadocia by his father King Mithridates VI of Pontus after the assas ...

as king, with Gordius as regent. In 97 Cappadocia rebelled, but the uprising was swiftly put down by Mithridates. Afterwards, Mithridates and NicomedesIII both sent embassies to Rome. The Roman Senate decreed that Mithridates had to withdraw from Cappadocia and Nicomedes from Paphlagonia. Mithridates obliged, and the Romans installed Ariobarzanes in Cappadocia. In 91/90BC, while Rome was busy in the Social War in Italy, Mithridates encouraged his new ally and son-in-law, King Tigranes the Great

Tigranes II, more commonly known as Tigranes the Great ( hy, Տիգրան Մեծ, ''Tigran Mets''; grc, Τιγράνης ὁ Μέγας ''Tigránes ho Mégas''; la, Tigranes Magnus) (140 – 55 BC) was King of Armenia under whom the ...

of Armenia, to invade Cappadocia, which he did, and Ariobarzanes fled to Rome. Mithridates then deposed NicomedesIV from Bithynia, placing Socrates Chrestus on the throne.

The First Mithridatic War

A Roman army under Manius Aquillius arrived in Asia Minor in 90BC, which prompted Mithridates and Tigranes to withdraw. Cappadocia and Bithynia were restored to their respective monarchs, but then faced large debts to Rome due to their bribes for the Roman senators, and NicomedesIV was eventually convinced by Aquillius to attack Pontus in order to repay the debts. He plundered as far as Amastris, and returned with much loot. Mithridates invaded Cappadocia once again, and Rome declared war. In the summer of 89 BC, Mithridates invaded Bithynia and defeated Nicomedes and Aquillius in battle. He moved swiftly into Roman Asia and resistance crumbled; by 88 he had obtained the surrender of most of the newly created province. He was welcomed in many cities, where the residents chafed under Romantax farming

Farming or tax-farming is a technique of financial management in which the management of a variable revenue stream is assigned by legal contract to a third party and the holder of the revenue stream receives fixed periodic rents from the contrac ...

. In 88 Mithridates also ordered the massacre of at least 80,000 Romans and Italians in what became known as the 'Asiatic Vespers

The Asiatic Vespers (also known as the Asian Vespers, Ephesian Vespers, or the Vespers of 88 BC) refers to the massacres of Roman and other Latin-speaking peoples living in parts of western Anatolia in 88 BC by forces loyal to Mithridates VI Eupat ...

'. Many Greek cities in Asia Minor happily carried out the orders; this ensured that they could no longer return to an alliance with Rome. In the autumn of 88 Mithridates also placed Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

under siege, but he failed to take it.

In Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, anti-Roman elements were emboldened by the news and soon formed an alliance with Mithridates. A joint Pontic–Athenian naval expedition took Delos in 88BC, and granted the city to Athens. Many Greek city-states now joined Mithridates, including Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

, the Achaean League

The Achaean League ( Greek: , ''Koinon ton Akhaion'' "League of Achaeans") was a Hellenistic-era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea in the northwestern P ...

, and most of the Boeotian League

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, Βοιωτία; modern: ; ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, and its la ...

except Thespiae

Thespiae ( ; grc, Θεσπιαί, Thespiaí) was an ancient Greek city (''polis'') in Boeotia. It stood on level ground commanded by the low range of hills which run eastward from the foot of Mount Helicon to Thebes, near modern Thespies.

Histo ...

. Finally, in 87 BC, Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla ha ...

set out from Italy with five legions. He marched through Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, Βοιωτία; modern: ; ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, and its ...

, which quickly surrendered, and began laying siege to Athens and the Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saron ...

(the Athenian port city, no longer connected by the Long Walls

Although long walls were built at several locations in ancient Greece, notably Corinth and Megara, the term Long Walls ( grc, Μακρὰ Τείχη ) generally refers to the walls that connected Athens main city to its ports at Piraeus and Phal ...

). Athens fell in March 86BC, and the city was sacked. After stiff resistance, Archelaus, the Pontic general in Piraeus, left by sea, and Sulla utterly destroyed the port city. Meanwhile, Mithridates had sent his son Arcathias with a large army via Thrace into Greece.

Sulla now headed north, seeking the fertile plains of Boeotia to supply his army. At the Battle of Chaeronea, Sulla inflicted severe casualties on Archelaus, who nevertheless retreated and continued to raid Greece with the Pontic fleet. Archelaus regrouped and attacked a second time at the

Sulla now headed north, seeking the fertile plains of Boeotia to supply his army. At the Battle of Chaeronea, Sulla inflicted severe casualties on Archelaus, who nevertheless retreated and continued to raid Greece with the Pontic fleet. Archelaus regrouped and attacked a second time at the Battle of Orchomenus

The Battle of Orchomenus was fought in 85 BC between Rome and the forces of Mithridates VI of Pontus. The Roman army was led by Lucius Cornelius Sulla, while Mithridates' army was led by Archelaus. The Roman force was victorious, and Archel ...

in 85BC but was once again defeated and suffered heavy losses. As a result of the losses and the unrest they stirred in Asia Minor, as well as the presence of the Roman army now campaigning in Bithynia, Mithridates was forced to accept a peace deal. Mithridates and Sulla met in 85BC at Dardanus. Sulla decreed that Mithridates had to surrender Roman Asia and return Bithynia and Cappadocia to their former kings. He also had to pay 2,000 talents and provide ships. Mithridates would retain the rest of his holdings and become an ally of Rome.

Second and Third Mithridatic wars

The treaty agreed with Sulla was not to last. From 83 to 82BC Mithridates fought against and defeated Licinius Murena, who had been left by Sulla to organize the province of Asia. The so-called Second Mithridatic war ended without any territorial gains by either side. The Romans now began securing the coastal region of Lycia and Pamphylia from pirates and established control overPisidia

Pisidia (; grc-gre, Πισιδία, ; tr, Pisidya) was a region of ancient Asia Minor located north of Pamphylia, northeast of Lycia, west of Isauria and Cilicia, and south of Phrygia, corresponding roughly to the modern-day province of Ant ...

and Lycaonia

Lycaonia (; el, Λυκαονία, ''Lykaonia''; tr, Likaonya) was a large region in the interior of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), north of the Taurus Mountains. It was bounded on the east by Cappadocia, on the north by Galatia, on the west by ...

. When in 74 the consul Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (; 118–57/56 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, closely connected with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In culmination of over 20 years of almost continuous military and government service, he conquered the eastern kingd ...

took over Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

, Mithridates faced Roman commanders on two fronts. The Cilician pirates had not been completely defeated, and Mithridates signed an alliance with them. He was also allied with the government of Quintus Sertorius

Quintus Sertorius (c. 126 – 73 BC) was a Roman general and statesman who led a large-scale rebellion against the Roman Senate on the Iberian peninsula. He had been a prominent member of the populist faction of Cinna and Marius. During the l ...

in Spain and with his help reorganized some of his troops in the Roman legionary pattern with short stabbing swords.

The Third Mithridatic war

The Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC), the last and longest of the three Mithridatic Wars, was fought between Mithridates VI of Pontus and the Roman Republic. Both sides were joined by a great number of allies dragging the entire east of the ...

broke out when NicomedesIV of Bithynia died without heirs in 75 and left his kingdom to Rome. In 74BC Rome mobilized its armies in Asia Minor, probably provoked by some move made by Mithridates, but our sources are not clear on this. In 73 Mithridates invaded Bithynia, and his fleet defeated the Romans off Chalcedon

Chalcedon ( or ; , sometimes transliterated as ''Chalkedon'') was an ancient maritime town of Bithynia, in Asia Minor. It was located almost directly opposite Byzantium, south of Scutari (modern Üsküdar) and it is now a district of the cit ...

and laid siege to Cyzicus

Cyzicus (; grc, Κύζικος ''Kúzikos''; ota, آیدینجق, ''Aydıncıḳ'') was an ancient Greek town in Mysia in Anatolia in the current Balıkesir Province of Turkey. It was located on the shoreward side of the present Kapıdağ Peni ...

. Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (; 118–57/56 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, closely connected with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In culmination of over 20 years of almost continuous military and government service, he conquered the eastern kingd ...

marched from Phrygia with his five legions and forced Mithridates to retreat to Pontus. In 72BC Lucullus invaded Pontus through Galatia and marched north following the river Halys to the north coast, he besieged Amisus, which withstood until 70BC. In 71 he marched through the Iris and Lycus river valleys and established his base in Cabeira. Mithridates sent his cavalry to cut the Roman supply line to Cappadocia in the south, but they suffered heavy casualties. Mithridates, still unwilling to fight a decisive engagement, now began a retreat to Lesser Armenia

Lesser Armenia ( hy, Փոքր Հայք, ''Pokr Hayk''; la, Armenia Minor, Greek: Mikre Armenia, Μικρή Αρμενία), also known as Armenia Minor and Armenia Inferior, comprised the Armenian–populated regions primarily to the west and n ...

, where he expected aid from his ally Tigranes the Great. Because of his now weakened cavalry, the retreat turned into an all-out rout, and most of the Pontic army was destroyed or captured. These events led Machares, the son of Mithridates and ruler of the Crimean Bosporus, to seek an alliance with Rome. Mithridates fled to Armenia.

In the summer of 69 Lucullus invaded Armenian territory, marching with 12,000 men through Cappadocia into Sophene

Sophene ( hy, Ծոփք, translit=Tsopkʻ, grc, Σωφηνή, translit=Sōphēnē or hy, Չորրորդ Հայք, lit=Fourth Armenia) was a province of the ancient kingdom of Armenia, located in the south-west of the kingdom, and of the Ro ...

. His target was Tigranocerta __NOTOC__

Tigranocerta ( el, Τιγρανόκερτα, ''Tigranόkerta''; Tigranakert; hy, Տիգրանակերտ), also called Cholimma or Chlomaron in antiquity, was a city and the capital of the Armenian Kingdom between 77 and 69 BCE. It bore ...

, the new capital of Tigranes's empire. Tigranes retreated to gather his forces. Lucullus laid siege to the city, and Tigranes returned with his army, including large numbers of heavily armored cavalrymen, termed Cataphracts

A cataphract was a form of armored heavy cavalryman that originated in Persia and was fielded in ancient warfare throughout Eurasia and Northern Africa.

The English word derives from the Greek ' (plural: '), literally meaning "armored" or "co ...

, vastly outnumbering Lucullus' force. Despite this, Lucullus led his men in a charge against the Armenian horses and won a great victory at the Battle of Tigranocerta. Tigranes fled north while Lucullus destroyed his new capital city and dismantled his holdings in the south by granting independence to Sophene and returning Syria to the Seleucid king Antiochus XIII Asiaticus

Antiochus XIII Philadelphus, (Greek: Ἀντίοχος ΙΓ' Φιλάδελφος) known as Asiaticus, (Ἀσιατικός) was the penultimate ruler of the Seleucid kingdom.

Biography

He was son of king Antiochus X Eusebes and the Ptolemaic ...

. In 68BC Lucullus invaded northern Armenia, ravaging the country and capturing Nisibis

Nusaybin (; '; ar, نُصَيْبِيْن, translit=Nuṣaybīn; syr, ܢܨܝܒܝܢ, translit=Nṣībīn), historically known as Nisibis () or Nesbin, is a city in Mardin Province, Turkey. The population of the city is 83,832 as of 2009 and is ...

, but Tigranes avoided battle. Meanwhile, Mithridates invaded Pontus, and in 67 he defeated a large Roman force near Zela. Lucullus, now in command of tired and discontented troops, withdrew to Pontus, then to Galatia. He was replaced by two new consuls arriving from Italy with fresh legions, Marcius Rex and Acilius Glabrio. Mithridates now recovered Pontus while Tigranes invaded Cappadocia.

In response to increasing pirate activity in the eastern Mediterranean, the senate granted Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

extensive proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military command, or ...

ar Imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic a ...

throughout the Mediterranean in 67BC. Pompey eliminated the pirates, and in 66 he was assigned command in Asia Minor to deal with Pontus. Pompey organized his forces, close to 45,000 legionaries, including Lucullus' troops, and signed an alliance with the Parthians, who attacked and kept Tigranes busy in the east. Mithridates massed his army, some 30,000 men and 2,000–3,000 cavalry, in the heights of Dasteira in lesser Armenia. Pompey fought to encircle him with earthworks for six weeks, but Mithridates eventually retreated north. Pompey pursued and managed to catch his forces by surprise in the night, and the Pontic army suffered heavy casualties. After the battle, Pompey founded the city of Nicopolis. Mithridates fled to Colchis, and later to his son Machares in the Crimea in 65BC. Pompey now headed east into Armenia, where Tigranes submitted to him, placing his royal diadem at his feet. Pompey took most of Tigranes' empire in the east but allowed him to remain as king of Armenia. Meanwhile, Mithridates was organizing a defense of the Crimea when his son Pharnaces led the army in revolt; Mithridates was forced to commit suicide or was assassinated.

Roman province and client kingdoms

Most of the western half of Pontus and the Greek cities of the coast, including Sinope, were annexed by Rome directly as part of the Roman province ofBithynia et Pontus

Bithynia and Pontus ( la, Provincia Bithynia et Pontus, Ancient Greek ) was the name of a province of the Roman Empire on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). It was formed during the late Roman Republic by the amalgamation o ...

. The interior and eastern coast remained an independent client kingdom. The Bosporan Kingdom

The Bosporan Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus (, ''Vasíleio toú Kimmerikoú Vospórou''), was an ancient Greco-Scythian state located in eastern Crimea and the Taman Peninsula on the shores of the Cimmerian Bosporus, ...

also remained independent under Pharnaces II of Pontus

Pharnaces II of Pontus ( grc-gre, Φαρνάκης; about 97–47 BC) was the king of the Bosporan Kingdom and Kingdom of Pontus until his death. He was a monarch of Persian and Greek ancestry. He was the youngest child born to King Mithrida ...

as an ally and friend of Rome. Colchis was also made into a client kingdom. PharnacesII later made an attempt at reconquering Pontus. During the civil war of Caesar and Pompey, he invaded Asia Minor (48BC), taking Colchis, lesser Armenia, Pontus, and Cappadocia and defeating a Roman army at Nicopolis. Caesar responded swiftly and defeated him at Zela, where he uttered the famous phrase 'Veni, vidi, vici

''Veni, vidi, vici'' (, ; "I came; I saw; I conquered") is a Latin phrase used to refer to a swift, conclusive victory. The phrase is popularly attributed to Julius Caesar who, according to Appian, used the phrase in a letter to the Roman Senate ...

'.John Hazel "Who's who in the Greek world", p. 179. Pontic kings continued to rule the client Kingdom of Pontus, Colchis, and Cilicia until PolemonII was forced to abdicate the Pontic throne by Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unti ...

in AD 62.

Coinage

Although the Pontic kings claimed descent from the Persian royal house, they generally acted as Hellenistic kings and portrayed themselves as such in their coins, mimicking Alexander's royal ''stater''.Military

Thearmy

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

of the Pontic Kingdom had a varied ethnic composition, as it recruited its soldiers from all over the kingdom. The standing army included Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diasp ...

, Bithynians, Cappadocians

Cappadocian Greeks also known as Greek Cappadocians ( el, Έλληνες-Καππαδόκες, Ελληνοκαππαδόκες, Καππαδόκες; tr, Kapadokyalı Rumlar) or simply Cappadocians are an ethnic Greek community native to the ...

, Galatians Galatians may refer to:

* Galatians (people)

* Epistle to the Galatians, a book of the New Testament

* English translation of the Greek ''Galatai'' or Latin ''Galatae'', ''Galli,'' or ''Gallograeci'' to refer to either the Galatians or the Gauls in ...

, Heniochoi, Iazyges

The Iazyges (), singular Ἰάζυξ. were an ancient Sarmatian tribe that traveled westward in BC from Central Asia to the steppes of modern Ukraine. In BC, they moved into modern-day Hungary and Serbia near the Dacian steppe between th ...

, Koralloi, Leucosyrians, Phrygians, Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

, Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

, Tauri

The Tauri (; in Ancient Greek), or Taurians, also Scythotauri, Tauri Scythae, Tauroscythae (Pliny, ''H. N.'' 4.85) were an ancient people settled on the southern coast of the Crimea peninsula, inhabiting the Crimean Mountains in the 1st millenn ...

, Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

and Vasternoi, as well as soldiers from other areas around the Black Sea. The Greeks who served in the military were not part of the standing army, but rather fought as citizens of their respective cities.Stefanidou Vera, "Kingdom of Pontus", 2008, Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor/ref> Like many

Hellenistic armies

The Hellenistic armies is the term applied to the armies of the successor kingdoms of the Hellenistic period. The Hellenistic armies emerged after the death of Alexander the Great, when his vast empire was split between his successors, also know ...

, the army of Pontus adopted the Macedonian phalanx

The Macedonian phalanx ( gr, Μακεδονική φάλαγξ) was an infantry formation developed by Philip II from the classical Greek phalanx, of which the main innovation was the use of the sarissa, a 6 meter pike. It was famously commanded ...

; it fielded a corps of ''Chalkaspides The ''Chalkaspides'' ( el, Χαλκάσπιδες "Bronze Shields") made up one of the two probable corps of the Antigonid-era Macedonian phalanx in the Hellenistic period, with the '' Leukaspides'' ("White Shields") forming the other.

''Chalkaspi ...

'' ('bronze-shields'), for example against Sulla at the Battle of Chaeronea, while at the same battle 15,000 phalangites were recruited from freed slaves. Pontus also fielded various cavalry units, including cataphract

A cataphract was a form of armored heavy cavalryman that originated in Persia and was fielded in ancient warfare throughout Eurasia and Northern Africa.

The English word derives from the Greek ' (plural: '), literally meaning "armored" or ...

s. In addition to normal cavalry Pontus also fielded scythed chariots. Under Mithridates VI Pontus also fielded a corps of 120,000 troops armed "in the Roman fashion" and "drilled in the Roman phalanx formation".Plutarch, Life of Lucullus. 7.4 These units imitated Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period o ...

s, although it is disputed to what degree they achieved this.

The navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

was organized in a similar fashion as the army. While the kingdom itself provided the main contingent of ships, a small portion represented the Greek cities. The crewmen either came from the various tribes of the kingdom, or were of Greek origin.

See also

*Bosporan Kingdom

The Bosporan Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus (, ''Vasíleio toú Kimmerikoú Vospórou''), was an ancient Greco-Scythian state located in eastern Crimea and the Taman Peninsula on the shores of the Cimmerian Bosporus, ...

* Ethnarchy of Comana

Notes

Bibliography

Modern sources

* * *Ancient sources

* Polybius, the histories. * Appian, the foreign wars. * Memnon of Heraclea, history of Heraclea. * Strabo, Geographica. * Plutarch, ''Parallel lives''. 'Demetrius'. {{DEFAULTSORT:PontusKingdom Of Pontus

Pontus ( grc-gre, Πόντος ) was a Hellenistic kingdom centered in the historical region of Pontus and ruled by the Mithridatic dynasty (of Persian origin), which possibly may have been directly related to Darius the Great of the Achaemen ...

Classical Anatolia

History of the Black Sea

3rd-century BC establishments

States and territories established in the 3rd century BC

281 BC

280s BC establishments

62 disestablishments

Achaemenid Empire

States and territories disestablished in the 1st century

History of Trabzon Province

History of Rize Province

History of Giresun Province

History of Amasya Province

History of Tokat Province

Iranian dynasties

Roman client kingdoms

Zoroastrianism

Ancient history of Ukraine

History of Odesa Oblast

History of Mykolaiv Oblast

History of Kherson Oblast

Former kingdoms