The Communist Manifesto on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Communist Manifesto'' (), originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (), is a political pamphlet written by

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The text is the first and most systematic attempt by Marx and Engels to codify for wide consumption the historical materialist idea that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles", in which social classes are defined by the relationship of people to the means of production. Published amid the

In spring 1847, Marx and Engels joined the League of the Just, who were quickly convinced by the duo's ideas of "critical communism". At its First Congress in 2–9 June, the League tasked Engels with drafting a "profession of faith", but such a document was later deemed inappropriate for an open, non-confrontational organisation. Engels nevertheless wrote the "Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith", detailing the League's programme. A few months later, in October, Engels arrived at the League's Paris branch to find that Moses Hess had written an inadequate manifesto for the group, now called the League of Communists. In Hess's absence, Engels severely criticised this manifesto, and convinced the rest of the League to entrust him with drafting a new one. This became the draft '' Principles of Communism'', described as "less of a credo and more of an exam paper".

On 23 November, just before the Communist League's Second Congress (29 November – 8 December 1847), Engels wrote to Marx, expressing his desire to eschew the catechism format in favour of the manifesto, because he felt it "must contain some history." On the 28th, Marx and Engels met at

In spring 1847, Marx and Engels joined the League of the Just, who were quickly convinced by the duo's ideas of "critical communism". At its First Congress in 2–9 June, the League tasked Engels with drafting a "profession of faith", but such a document was later deemed inappropriate for an open, non-confrontational organisation. Engels nevertheless wrote the "Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith", detailing the League's programme. A few months later, in October, Engels arrived at the League's Paris branch to find that Moses Hess had written an inadequate manifesto for the group, now called the League of Communists. In Hess's absence, Engels severely criticised this manifesto, and convinced the rest of the League to entrust him with drafting a new one. This became the draft '' Principles of Communism'', described as "less of a credo and more of an exam paper".

On 23 November, just before the Communist League's Second Congress (29 November – 8 December 1847), Engels wrote to Marx, expressing his desire to eschew the catechism format in favour of the manifesto, because he felt it "must contain some history." On the 28th, Marx and Engels met at

A French translation of the ''Manifesto'' was published just before the working-class June Days Uprising was crushed. Its influence in the Europe-wide

A French translation of the ''Manifesto'' was published just before the working-class June Days Uprising was crushed. Its influence in the Europe-wide

Following the October Revolution of 1917 that swept the

Following the October Revolution of 1917 that swept the

In contrast, critics such as revisionist Marxist and reformist socialist

In contrast, critics such as revisionist Marxist and reformist socialist

Chapter 11: The Translation of ''The Communist Manifesto''

/small> * Hal Draper, ''The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto.'' 994Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020. * Dirk J. Struik (ed.), ''Birth of the Communist Manifesto.'' New York: International Publishers, 1971.

''The Communist Manifesto''

at the Marxists Internet Archive

''Manifesto of the Communist Party''

an English-language translation by Progress Publishers, in PDF format

''The Communist Manifesto''

in 80 world languages *

Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei : veröffentlicht im Februar 1848

' Original 1848 edition in full colour scan *

Democracy and the Communist Manifesto

On the ''Communist Manifesto''

at modkraft.dk (a collection of links to bibliographical and historical materials, and contemporary analyses) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Communist Manifesto, The 1848 books 1848 in politics Books about communism Books by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels Books critical of capitalism Political manifestos Memory of the World Register Pamphlets Historical materialism Censored books

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The text is the first and most systematic attempt by Marx and Engels to codify for wide consumption the historical materialist idea that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles", in which social classes are defined by the relationship of people to the means of production. Published amid the

Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

in Europe, the manifesto remains one of the world's most influential political documents.

Marx and Engels combine philosophical materialism with the Hegelian dialectical method in order to analyze the development of European society through its modes of production, including primitive communism, antiquity, feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

, and capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

, noting the emergence of a new, dominant class at each stage. The text outlines the relationship between the means of production, relations of production, forces of production, and the mode of production, and posits that changes in society's economic "base" affect changes in its "superstructure". Marx and Engels assert that capitalism is marked by the exploitation of the proletariat ( working class of wage labourers) by the ruling bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

, which is "constantly revolutionising the instruments ndrelations of production, and with them the whole relations of society". They argue that capital's need for a flexible labour force dissolves the old relations, and that its global expansion in search of new markets creates "a world after its own image".

The ''Manifesto'' concludes that capitalism does not offer humanity the possibility of self-realization, instead ensuring that humans are perpetually stunted and alienated. It theorizes that capitalism will bring about its own destruction by polarizing and unifying the proletariat, and predicts that a revolution will lead to the emergence of communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, a classless society in which "the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all". Marx and Engels propose the following transitional policies: the abolition of private property in land and inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offi ...

; introduction of a progressive income tax; confiscation of rebels' property; nationalisation of credit, communication, and transport; expansion and integration of industry and agriculture; enforcement of universal obligation of labour; and provision of universal education and abolition of child labour

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation w ...

. The text ends with three decisive sentences, reworked and popularized into the famous call for solidarity, the slogan "Workers of the world, unite!

The political slogan "Workers of the world, unite!" is one of the rallying cries from ''The Communist Manifesto'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (, literally , but soon popularised in English language, English as "Workers of the wo ...

You have nothing to lose but your chains".

Synopsis

''The Communist Manifesto'' is divided into a preamble and four sections. The introduction begins: "A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre ofcommunism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

." Pointing out that it was widespread for politicians—both those in government and those in the opposition—to label their opponents as communists, the authors infer that those in power acknowledge communism to be a power in itself. Subsequently, the introduction exhorts communists to openly publish their views and aims, which is the very function of the manifesto.

The first section of the ''Manifesto'', "Bourgeois and Proletarians", outlines historical materialism

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of Class society, class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

Karl Marx stated that Productive forces, techno ...

, and states that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". According to the authors, all societies in history had taken the form of an oppressed majority exploited by an oppressive minority. In Marx and Engels' time, they say that under capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

, the industrial working class, or ' proletariat', engages in class struggle against the owners of the means of production, the 'bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

'. The bourgeoisie, through the "constant revolutionising of production nduninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions" have emerged as the supreme class in society, displacing all the old powers of feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

. The bourgeoisie constantly exploits the proletariat for its labour power, creating profit for themselves and accumulating capital. In doing so, however, Marx and Engels describe the bourgeoisie as serving as "its own grave-diggers"; as they believe the proletariat will inevitably become conscious of their own potential and rise to power through revolution, overthrowing the bourgeoisie.

"Proletarians and Communists", the second section, starts by stating the relationship of 'conscious communists' (i.e., those who identify as communists) to the rest of the working class. The communists' party will not oppose other working-class parties, but unlike them, it will express the general will and defend the common interests of the world's proletariat as a whole, independent of all nationalities. The section goes on to defend communism from various objections, including claims that it advocates communal prostitution or disincentivises people from working. The section ends by outlining a set of short-term demands—among them a progressive income tax; abolition of inheritances and private property; abolition of child labour

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation w ...

; free public education; nationalisation of the means of transport and communication; centralisation of credit via a national bank; expansion of publicly owned land, etc.—the implementation of which is argued would result in the precursor to a stateless and classless society.

The third section, "Socialist and Communist Literature", distinguishes communism from other socialist doctrines prevalent at the time—these being broadly categorised as Reactionary Socialism; Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism; and Critical-Utopian Socialism and Communism. While the degree of reproach toward rival perspectives varies, all are dismissed for advocating reformism and failing to recognise the pre-eminent revolutionary role of the working class.

"Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Opposition Parties", the concluding section of the ''Manifesto'', briefly discusses the communist position on struggles in specific countries in the mid-nineteenth century such as in France, Switzerland, Poland, and lastly Germany, which is said to be "on the eve of a bourgeois revolution" and predicts that a world revolution will soon follow. It ends by declaring an alliance with the democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing economic and political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-mana ...

s, boldly supporting other communist revolutions and calling for united international proletarian action—" Working Men of All Countries, Unite!"

Writing

In spring 1847, Marx and Engels joined the League of the Just, who were quickly convinced by the duo's ideas of "critical communism". At its First Congress in 2–9 June, the League tasked Engels with drafting a "profession of faith", but such a document was later deemed inappropriate for an open, non-confrontational organisation. Engels nevertheless wrote the "Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith", detailing the League's programme. A few months later, in October, Engels arrived at the League's Paris branch to find that Moses Hess had written an inadequate manifesto for the group, now called the League of Communists. In Hess's absence, Engels severely criticised this manifesto, and convinced the rest of the League to entrust him with drafting a new one. This became the draft '' Principles of Communism'', described as "less of a credo and more of an exam paper".

On 23 November, just before the Communist League's Second Congress (29 November – 8 December 1847), Engels wrote to Marx, expressing his desire to eschew the catechism format in favour of the manifesto, because he felt it "must contain some history." On the 28th, Marx and Engels met at

In spring 1847, Marx and Engels joined the League of the Just, who were quickly convinced by the duo's ideas of "critical communism". At its First Congress in 2–9 June, the League tasked Engels with drafting a "profession of faith", but such a document was later deemed inappropriate for an open, non-confrontational organisation. Engels nevertheless wrote the "Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith", detailing the League's programme. A few months later, in October, Engels arrived at the League's Paris branch to find that Moses Hess had written an inadequate manifesto for the group, now called the League of Communists. In Hess's absence, Engels severely criticised this manifesto, and convinced the rest of the League to entrust him with drafting a new one. This became the draft '' Principles of Communism'', described as "less of a credo and more of an exam paper".

On 23 November, just before the Communist League's Second Congress (29 November – 8 December 1847), Engels wrote to Marx, expressing his desire to eschew the catechism format in favour of the manifesto, because he felt it "must contain some history." On the 28th, Marx and Engels met at Ostend

Ostend ( ; ; ; ) is a coastal city and municipality in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerke, Raversijde, Stene and Zandvoorde, and the city of Ostend proper – the la ...

in Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, and a few days later, gathered at the Soho, London headquarters of the German Workers' Education Association to attend the Congress. Over the next ten days, intense debate raged between League functionaries; Marx eventually dominated the others and, overcoming "stiff and prolonged opposition", in Harold Laski's words, secured a majority for his programme. The League thus unanimously adopted a far more combative resolution than that at the First Congress in June. Marx (especially) and Engels were subsequently commissioned to draw up a manifesto for the League.

Upon returning to Brussels, Marx engaged in "ceaseless procrastination", according to his biographer Francis Wheen. Working only intermittently on the ''Manifesto'', he spent much of his time delivering lectures on political economy at the German Workers' Education Association, writing articles for the ', and giving a long speech on free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

. Following this, he even spent a week (17–26 January 1848) in Ghent to establish a branch of the Democratic Association there. Subsequently, having not heard from Marx for nearly two months, the Central Committee of the Communist League sent him an ultimatum on 24 or 26 January, demanding he submit the completed manuscript by 1 February. This imposition spurred Marx on, who struggled to work without a deadline, and he seems to have rushed to finish the job in time. For evidence of this, historian Eric Hobsbawm

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm (; 9 June 1917 – 1 October 2012) was a British historian of the rise of industrial capitalism, socialism and nationalism. His best-known works include his tetralogy about what he called the "long 19th century" (''Th ...

points to the absence of rough drafts, only one page of which survives.

In all, the ''Manifesto'' was written over 6–7 weeks. Although Engels is credited as co-writer, the final draft was penned exclusively by Marx. From the 26 January letter, Laski infers that even the Communist League considered Marx to be the sole draftsman and that he was merely their agent, imminently replaceable. Further, Engels himself wrote in 1883: "The basic thought running through the ''Manifesto'' ..belongs solely and exclusively to Marx". Although Laski does not disagree, he suggests that Engels underplays his own contribution with characteristic modesty and points out the "close resemblance between its substance and that of the 'Principles of Communism''. Laski argues that while writing the ''Manifesto'', Marx drew from the "joint stock of ideas" he developed with Engels "a kind of intellectual bank account upon which either could draw freely".

Publication

Initial publication and obscurity, 1848–1872

In late February 1848, the ''Manifesto'' was anonymously published by the Communist Workers' Educational Association (''Kommunistischer Arbeiterbildungsverein''), based at 46 Liverpool Street, in the Bishopsgate Without area of theCity of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

. Written in German, the 23-page pamphlet was titled ''Manifest der kommunistischen Partei'' and had a dark-green cover. It was reprinted three times and serialised in the ''Deutsche Londoner Zeitung'', a newspaper for German ''émigré''s. On 4 March, one day after the serialisation in the ''Zeitung'' began, Marx was expelled by Belgian police. Two weeks later, around 20 March, a thousand copies of the ''Manifesto'' reached Paris, and from there to Germany in early April. In April–May the text was corrected for printing and punctuation mistakes; Marx and Engels would use this 30-page version as the basis for future editions of the ''Manifesto''.

Although the ''Manifesto''s prelude announced that it was "to be published in the English, French, German, Italian, Flemish and Danish languages", the initial printings were only in German. Polish and Danish translations soon followed the German original in London, and by the end of 1848, a Swedish translation was published with a new title—''The Voice of Communism: Declaration of the Communist Party''. In November 1850 the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' was published in English for the first time when George Julian Harney serialised Helen Macfarlane's translation in his Chartist newspaper '' The Red Republican''. Her version begins: "A frightful hobgoblin stalks throughout Europe. We are haunted by a ghost, the ghost of Communism". For her translation, the Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated ''Lancs'') is a ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Cumbria to the north, North Yorkshire and West Yorkshire to the east, Greater Manchester and Merseyside to the south, and the Irish Sea to ...

-based Macfarlane probably consulted Engels, who had abandoned his own English translation half way. Harney's introduction revealed the ''Manifesto''s hitherto-anonymous authors' identities for the first time.

A French translation of the ''Manifesto'' was published just before the working-class June Days Uprising was crushed. Its influence in the Europe-wide

A French translation of the ''Manifesto'' was published just before the working-class June Days Uprising was crushed. Its influence in the Europe-wide Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

was restricted to Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, where the Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

-based Communist League and its newspaper '' Neue Rheinische Zeitung'', edited by Marx, played an important role. Within a year of its establishment, in May 1849, the ''Zeitung'' was suppressed; Marx was expelled from Germany and had to seek lifelong refuge in London. In 1851, members of the Communist League's central board were arrested by the Prussian Secret Police. At their trial in Cologne 18 months later in late 1852 they were sentenced to 3–6 years' imprisonment. For Engels, the revolution was "forced into the background by the reaction that began with the defeat of the Paris workers in June 1848, and was finally excommunicated 'by law' in the conviction of the Cologne Communists in November 1852".

After the defeat of the 1848 revolutions the ''Manifesto'' fell into obscurity, where it remained throughout the 1850s and 1860s. Hobsbawm says that by November 1850 the ''Manifesto'' "had become sufficiently scarce for Marx to think it worth reprinting section III ..in the last issue of his hort-livedLondon magazine". Over the next two decades only a few new editions were published; these include an (unauthorised and occasionally inaccurate) 1869 Russian translation by Mikhail Bakunin in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

and an 1866 edition in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

—the first time the ''Manifesto'' was published in Germany. According to Hobsbawm: "By the middle 1860s virtually nothing that Marx had written in the past was any longer in print". However, John Cowell-Stepney did publish an abridged version in the ''Social Economist'' in August/September 1869, in time for the Basle Congress.

Rise, 1872–1917

In the early 1870s, the ''Manifesto'' and its authors experienced a revival in fortunes. Hobsbawm identifies three reasons for this. The first is the leadership role Marx played in the International Workingmen's Association (aka the First International). Secondly, Marx also came into much prominence among socialists—and equal notoriety among the authorities—for his support of theParis Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

of 1871, elucidated in '' The Civil War in France''. Lastly, and perhaps most significantly in the popularisation of the ''Manifesto'', was the treason trial of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP) leaders. During the trial prosecutors read the ''Manifesto'' out loud as evidence; this meant that the pamphlet could legally be published in Germany. Thus in 1872 Marx and Engels rushed out a new German-language edition, writing a preface that identified that several portions that became outdated in the quarter century since its original publication. This edition was also the first time the title was shortened to ''The Communist Manifesto'' (''Das Kommunistische Manifest''), and it became the version the authors based future editions upon. Between 1871 and 1873, the ''Manifesto'' was published in over nine editions in six languages; on 30 December 1871 it was published in the United States for the first time in '' Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly'' of New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. However, by the mid 1870s the ''Communist Manifesto'' remained Marx and Engels' only work to be even moderately well-known.

Over the next forty years, as social-democratic parties rose across Europe and parts of the world, so did the publication of the ''Manifesto'' alongside them, in hundreds of editions in thirty languages. Marx and Engels wrote a new preface for the 1882 Russian edition, translated by Georgi Plekhanov in Geneva. In it they wondered if Russia could directly become a communist society, or if she would become capitalist first like other European countries. After Marx's death in 1883, Engels provided the prefaces for five editions between 1888 and 1893. Among these is the 1888 English edition, translated by Samuel Moore and approved by Engels, who also provided notes throughout the text. It has been the standard English-language edition ever since.

The principal region of its influence, in terms of editions published, was in the "central belt of Europe", from Russia in the east to France in the west. In comparison, the pamphlet had little impact on politics in southwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A '' compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west— ...

and southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a geographical sub-region of Europe, consisting primarily of the region of the Balkans, as well as adjacent regions and Archipelago, archipelagos. There are overlapping and conflicting definitions of t ...

, and moderate presence in the north. Outside Europe, Chinese and Japanese translations were published, as were Spanish editions in Latin America. The first Chinese edition of the book was translated by Zhu Zhixin after the 1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, th ...

in a Tongmenghui newspaper along with articles on socialist movements in Europe, North America, and Japan. This uneven geographical spread in the ''Manifesto''s popularity reflected the development of socialist movements in a particular region as well as the popularity of Marxist variety of socialism there. There was not always a strong correlation between a social-democratic party's strength and the ''Manifesto''s popularity in that country. For instance, the German SPD printed only a few thousand copies of the ''Communist Manifesto'' every year, but a few hundred thousand copies of the '' Erfurt Programme''. Further, the mass-based social-democratic parties of the Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

did not require their rank and file to be well-versed in theory; Marxist works such as the ''Manifesto'' or were read primarily by party theoreticians. On the other hand, small, dedicated militant parties and Marxist sects in the West took pride in knowing the theory; Hobsbawm says: "This was the milieu in which 'the clearness of a comrade could be gauged invariably from the number of earmarks on his Manifesto.

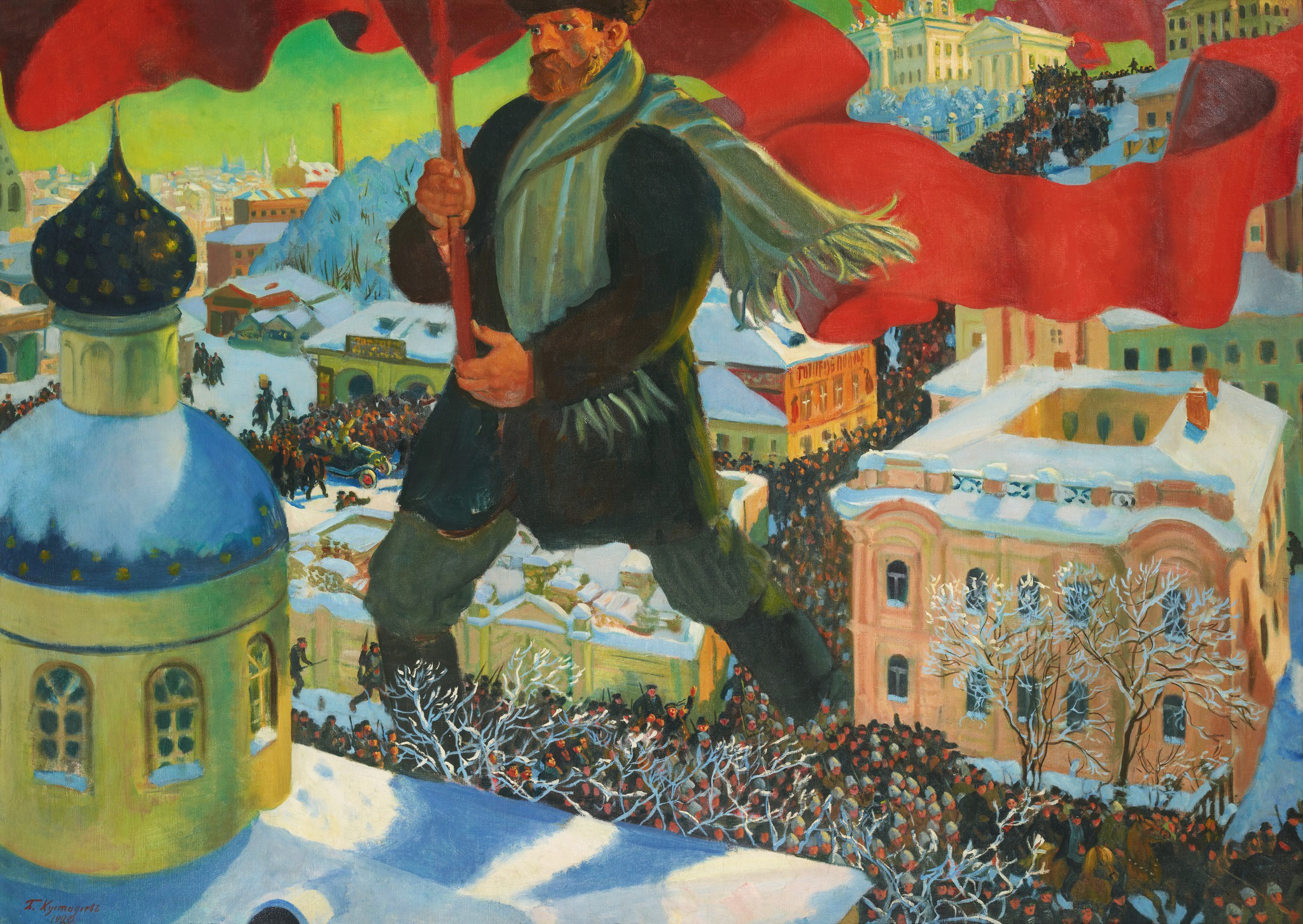

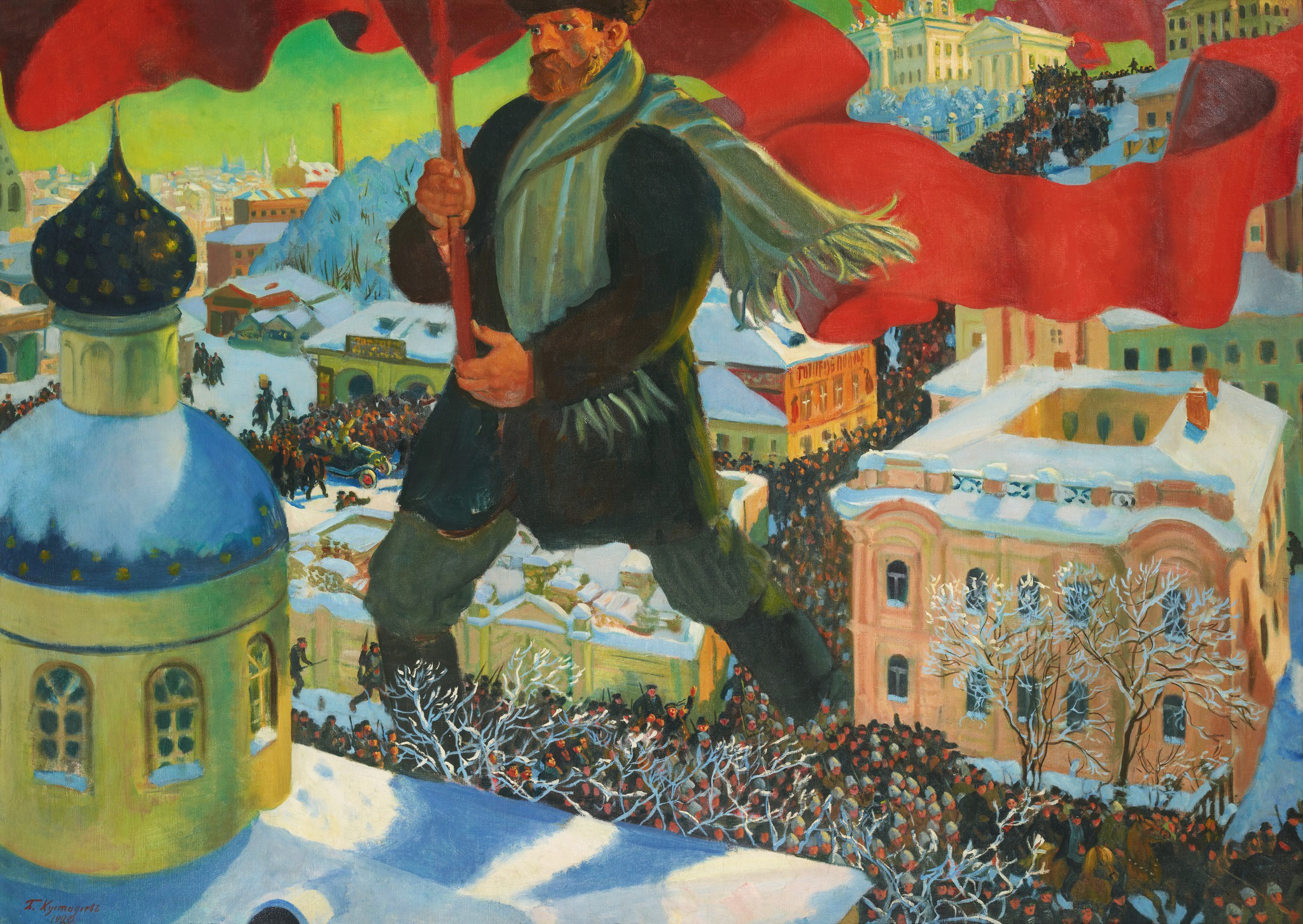

Ubiquity, 1917–present

Following the October Revolution of 1917 that swept the

Following the October Revolution of 1917 that swept the Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

-led Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

to power in Russia, the world's first socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. This article is about states that refer to themselves as socialist states, and not specifically ...

was founded explicitly along Marxist lines. The Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, which Bolshevik Russia would become a part of, was a one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

under the rule of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

(CPSU). Unlike their mass-based counterparts of the Second International, the CPSU and other Leninist parties like it in the Third International expected their members to know the classic works of Marx, Engels and Lenin. Further, party leaders were expected to base their policy decisions on Marxist–Leninist ideology. Therefore works such as the ''Manifesto'' were required reading for the party rank-and-file.

Widespread dissemination of Marx and Engels' works became an important policy objective; backed by a sovereign state, the CPSU had relatively inexhaustible resources for this purpose. Works by Marx, Engels, and Lenin were published on a very large scale, and cheap editions of their works were available in several languages across the world. These publications were either shorter writings or they were compendia such as the various editions of Marx and Engels' ''Selected Works'', or their '' Collected Works''. This affected the destiny of the ''Manifesto'' in several ways. Firstly, in terms of circulation; in 1932 the American and British Communist Parties printed several hundred thousand copies of a cheap edition for "probably the largest mass edition ever issued in English". Secondly the work entered political-science syllabuses in universities, which would only expand after the Second World War. For its centenary in 1948, its publication was no longer the exclusive domain of Marxists and academicians; general publishers too printed the ''Manifesto'' in large numbers. "In short, it was no longer only a classic Marxist document", Hobsbawm noted, "it had become a political classic tout court".

Total sales have been estimated at 500 million, and one of the four best-selling books of all time. In 1920, the ''Communist Manifesto'' was printed and distributed in Chinese. Chen Wangdao is credited as translator of the first printing.

Even after the collapse of the Soviet Bloc in the 1990s, the ''Communist Manifesto'' remains ubiquitous; Hobsbawm says that "In states without censorship, almost certainly anyone within reach of a good bookshop, and certainly anyone within reach of a good library, not to mention the internet, can have access to it". The 150th anniversary once again brought a deluge of attention in the press and the academia, as well as new editions of the book fronted by introductions to the text by academics. One of these, ''The Communist Manifesto: A Modern Edition'' by Verso, was touted by a critic in the ''London Review of Books

The ''London Review of Books'' (''LRB'') is a British literary magazine published bimonthly that features articles and essays on fiction and non-fiction subjects, which are usually structured as book reviews.

History

The ''London Review of Book ...

'' as being a "stylish red-ribboned edition of the work. It is designed as a sweet keepsake, an exquisite collector's item. In Manhattan, a prominent Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan in New York City. The avenue runs south from 143rd Street (Manhattan), West 143rd Street in Harlem to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. The se ...

store put copies of this choice new edition in the hands of shop-window mannequins, displayed in come-hither poses and fashionable décolletage".

Legacy

A number of late-20th- and 21st-century writers have commented on the ''Communist Manifesto''s continuing relevance. In a special issue of the '' Socialist Register'' commemorating the ''Manifesto''s 150th anniversary, Peter Osborne argued that it was "the single most influential text written in the nineteenth century". Academic John Raines in 2002 noted: "In our day this Capitalist Revolution has reached the farthest corners of the earth. The tool of money has produced the miracle of the new global market and the ubiquitous shopping mall. Read ''The Communist Manifesto'', written more than one hundred and fifty years ago, and you will discover that Marx foresaw it all". In 2003, English Marxist Chris Harman stated: "There is still a compulsive quality to its prose as it provides insight after insight into the society in which we live, where it comes from and where it's going to. It is still able to explain, as mainstream economists and sociologists cannot, today's world of recurrent wars and repeated economic crisis, of hunger for hundreds of millions on the one hand and ' overproduction' on the other. There are passages that could have come from the most recent writings on globalisation". Alex Callinicos, editor of '' International Socialism'', stated in 2010: "This is indeed a manifesto for the 21st century". Writing in '' The London Evening Standard'', Andrew Neather cited Verso Books' 2012 re-edition of ''The Communist Manifesto'' with an introduction byEric Hobsbawm

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm (; 9 June 1917 – 1 October 2012) was a British historian of the rise of industrial capitalism, socialism and nationalism. His best-known works include his tetralogy about what he called the "long 19th century" (''Th ...

as part of a resurgence of left-wing-themed ideas which includes the publication of Owen Jones' book '' Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class'' and Jason Barker's documentary '' Marx Reloaded''.

In contrast, critics such as revisionist Marxist and reformist socialist

In contrast, critics such as revisionist Marxist and reformist socialist Eduard Bernstein

Eduard Bernstein (; 6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German Marxist theorist and politician. A prominent member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), he has been both condemned and praised as a "Revisionism (Marxism), revisi ...

distinguished between "immature" early Marxism—as exemplified by ''The Communist Manifesto'' written by Marx and Engels in their youth—that he opposed for its violent Blanquist tendencies and later "mature" Marxism that he supported.Steger, Manfred B. ''The Quest for Evolutionary Socialism: Eduard Bernstein And Social Democracy''. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. pp. 236–37. This latter form refers to Marx in his later life seemingly claiming that socialism, under certain circumstances, could be achieved through peaceful means through legislative reform in democratic societies. Bernstein declared that the massive and homogeneous working-class claimed in the ''Communist Manifesto'' did not exist, and that contrary to claims of a proletarian majority emerging, the middle-class was growing under capitalism and not disappearing as Marx had claimed. Marx himself, later in his life, acknowledged that the Petite bourgeoisie

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, ; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a term that refers to a social class composed of small business owners, shopkeepers, small-scale merchants, semi- autonomous peasants, and artisans. They are named as s ...

was not disappearing in his work '' Theories of Surplus Value'' (1863). The obscurity of the later work means that Marx's acknowledgement of this error is not well known. George Boyer described the ''Manifesto'' as "very much a period piece, a document of what was called the 'hungry' 1840s"..

Hal Draper

Hal Draper (born Harold Dubinsky; September 19, 1914 – January 26, 1990) was an American socialist activist and author who played a significant role in the Berkeley, California, Free Speech Movement. He is known for his extensive scholarship on ...

rejected Bernstein's arguments about the middle class, stating that the ''Manifesto'' actually notes that, although individual members of this class are being constantly proletarianized, the class 'limps on, in a more and more ruined state'.

Many have drawn attention to the passage in the ''Manifesto'' that seems to sneer at the stupidity of the rustic: "The bourgeoisie ..draws all nations ..into civilisation ..It has created enormous cities ..and thus rescued a considerable part of the population from the idiocy icof rural life". However, as Eric Hobsbawm noted: In 2013, ''The Communist Manifesto'' was registered to UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

's Memory of the World Programme along with Marx's '' Capital, VolumeI''.

Influences

Marx and Engels' political influences were wide-ranging, reacting to and taking inspiration from German idealist philosophy, French socialism, and English and Scottish political economy. ''The Communist Manifesto'' also takes influence from literature. In Jacques Derrida's work, '' Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International'', he usesWilliam Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's '' Hamlet'' to frame a discussion of the history of the International, showing in the process the influence that Shakespeare's work had on Marx and Engels' writing. In his essay, "Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx", Christopher N. Warren makes the case that English poet John Milton also had a substantial influence on Marx and Engels' work. Historians of 19th-century reading habits have confirmed that Marx and Engels would have read these authors and it is known that Marx loved Shakespeare in particular. Milton, Warren argues, also shows a notable influence on ''The Communist Manifesto'', saying: "Looking back on Milton’s era, Marx saw a historical dialectic founded on inspiration in which freedom of the press, republicanism, and revolution were closely joined". Milton’s republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

, Warren continues, served as "a useful, if unlikely, bridge" as Marx and Engels sought to forge a revolutionary international coalition. The ''Manifesto'' also makes reference to the "revolutionary" antibourgeois social criticism of Thomas Carlyle, whom Engels had read as early as May 1843.

Editions

* *Footnotes

References

* Adoratsky, V. (1938). ''The History of the Communist Manifesto of Marx and Engels''. New York: International Publishers. * * * Hunt, Tristram (2009). ''Marx's General: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels''. Metropolitan Books. * *Further reading

* David Black, ''Helen Macfarlane: A Feminist, Revolutionary Journalist, and Philosopher in Mid-nineteenth-century England'', 2004./small> * Hal Draper, ''The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto.'' 994Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020. * Dirk J. Struik (ed.), ''Birth of the Communist Manifesto.'' New York: International Publishers, 1971.

External links

*''The Communist Manifesto''

at the Marxists Internet Archive

''Manifesto of the Communist Party''

an English-language translation by Progress Publishers, in PDF format

''The Communist Manifesto''

in 80 world languages *

Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei : veröffentlicht im Februar 1848

' Original 1848 edition in full colour scan *

Democracy and the Communist Manifesto

On the ''Communist Manifesto''

at modkraft.dk (a collection of links to bibliographical and historical materials, and contemporary analyses) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Communist Manifesto, The 1848 books 1848 in politics Books about communism Books by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels Books critical of capitalism Political manifestos Memory of the World Register Pamphlets Historical materialism Censored books