Tertiary Alcohols on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In chemistry, an alcohol is a type of organic compound that carries at least one hydroxyl () functional group bound to a

In chemistry, an alcohol is a type of organic compound that carries at least one hydroxyl () functional group bound to a

Alcohols have a long history of myriad uses. For simple mono-alcohols, which is the focus on this article, the following are most important industrial alcohols:.

*methanol, mainly for the production of formaldehyde and as a

Alcohols have a long history of myriad uses. For simple mono-alcohols, which is the focus on this article, the following are most important industrial alcohols:.

*methanol, mainly for the production of formaldehyde and as a

Al(C2H5)3 + 9 C2H4 -> Al(C8H17)3

:Al(C8H17)3 + 3O + 3 H2O -> 3 HOC8H17 + Al(OH)3

The process generates a range of alcohols that are separated by distillation.

Many higher alcohols are produced by hydroformylation of alkenes followed by hydrogenation. When applied to a terminal alkene, as is common, one typically obtains a linear alcohol:

:RCH=CH2 + H2 + CO -> RCH2CH2CHO

:RCH2CH2CHO + 3 H2 -> RCH2CH2CH2OH

Such processes give

The hydroboration-oxidation and

The hydroboration-oxidation and

2 R-OH + 2 NaH -> 2 R-O-Na+ + 2 H2

: 2 R-OH + 2 Na -> 2 R-O-Na+ + H2

The acidity of alcohols is strongly affected by solvation. In the gas phase, alcohols are more acidic than in water. In DMSO, alcohols (and water) have a p''K''a of around 29–32. As a consequence, alkoxides (and hydroxide) are powerful bases and nucleophiles (e.g., for the

Alcohols may, likewise, be converted to alkyl bromides using

Alcohols may, likewise, be converted to alkyl bromides using 3 R-OH + PBr3 -> 3 RBr + H3PO3

In the Barton-McCombie deoxygenation an alcohol is deoxygenated to an

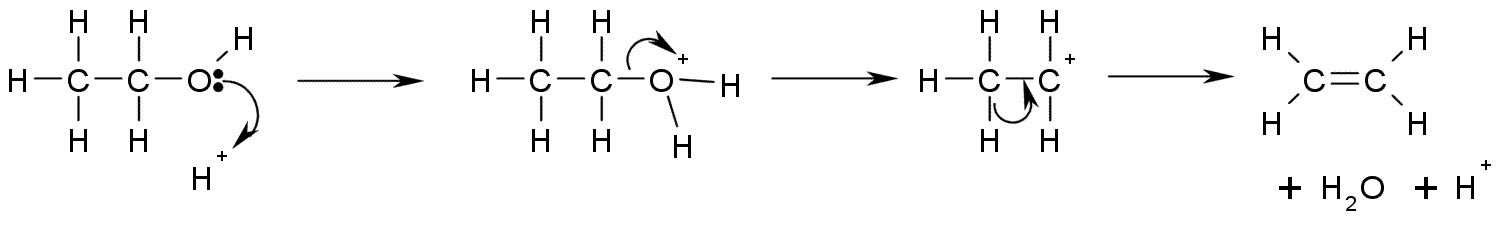

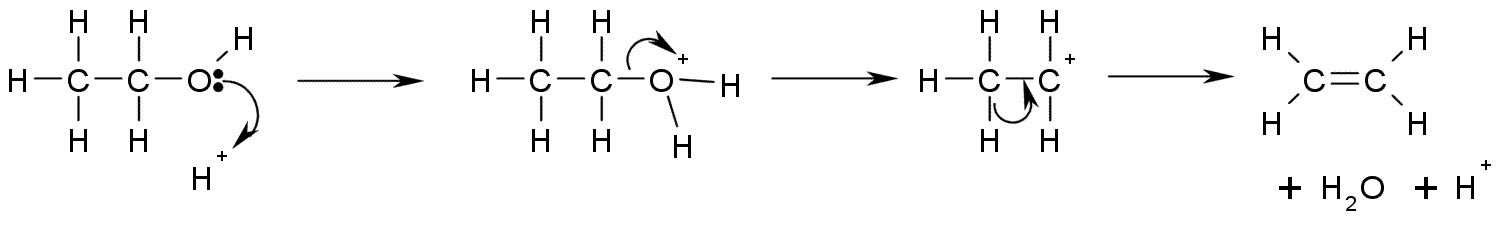

Upon treatment with strong acids, alcohols undergo the E1

Upon treatment with strong acids, alcohols undergo the E1  A more controlled elimination reaction requires the formation of the xanthate ester.

A more controlled elimination reaction requires the formation of the xanthate ester.

R-OH + R'-CO2H -> R'-CO2R + H2O

Other types of ester are prepared in a similar manner for example, tosyl (tosylate) esters are made by reaction of the alcohol with p- toluenesulfonyl chloride in pyridine.

Reagents useful for the transformation of primary alcohols to aldehydes are normally also suitable for the

Reagents useful for the transformation of primary alcohols to aldehydes are normally also suitable for the

In chemistry, an alcohol is a type of organic compound that carries at least one hydroxyl () functional group bound to a

In chemistry, an alcohol is a type of organic compound that carries at least one hydroxyl () functional group bound to a saturated

Saturation, saturated, unsaturation or unsaturated may refer to:

Chemistry

* Saturation, a property of organic compounds referring to carbon-carbon bonds

**Saturated and unsaturated compounds

**Degree of unsaturation

**Saturated fat or fatty acid ...

carbon atom. The term ''alcohol'' originally referred to the primary alcohol ethanol (ethyl alcohol), which is used as a drug and is the main alcohol present in alcoholic drink

An alcoholic beverage (also called an alcoholic drink, adult beverage, or a drink) is a drink that contains ethanol, a type of alcohol that acts as a drug and is produced by fermentation of grains, fruits, or other sources of sugar. The cons ...

s. An important class of alcohols, of which methanol and ethanol are the simplest examples, includes all compounds which conform to the general formula . Simple monoalcohols that are the subject of this article include primary (), secondary () and tertiary () alcohols.

The suffix ''-ol'' appears in the IUPAC chemical name of all substances where the hydroxyl group is the functional group with the highest priority. When a higher priority group is present in the compound, the prefix ''hydroxy-'' is used in its IUPAC

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC ) is an international federation of National Adhering Organizations working for the advancement of the chemical sciences, especially by developing nomenclature and terminology. It is ...

name. The suffix ''-ol'' in non-IUPAC names (such as paracetamol or cholesterol) also typically indicates that the substance is an alcohol. However, some compounds that contain hydroxyl functional groups have ''trivial names'' which do not include the suffix ''-ol'' or the prefix ''hydroxy-'', e.g. the sugars glucose and sucrose.

History

The inflammable nature of the exhalations of wine was already known to ancient natural philosophers such as Aristotle (384–322 BCE), Theophrastus (–287 BCE), and Pliny the Elder (23/24–79 CE). However, this did not immediately lead to the isolation of alcohol, even despite the development of more advanced distillation techniques in second- and third-century Roman Egypt. An important recognition, first found in one of the writings attributed to Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (ninth century CE), was that by adding salt to boiling wine, which increases the wine's relative volatility, the flammability of the resulting vapors may be enhanced. The distillation of wine is attested in Arabic works attributed toal-Kindī

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

(–873 CE) and to al-Fārābī

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Is ...

(–950), and in the 28th book of al-Zahrāwī's (Latin: Abulcasis, 936–1013) ''Kitāb al-Taṣrīf'' (later translated into Latin as ''Liber servatoris''). In the twelfth century, recipes for the production of ''aqua ardens'' ("burning water", i.e., alcohol) by distilling wine with salt started to appear in a number of Latin works, and by the end of the thirteenth century it had become a widely known substance among Western European chemists.

The works of Taddeo Alderotti (1223–1296) describe a method for concentrating alcohol involving repeated fractional distillation

Fractional distillation is the separation of a mixture into its component parts, or fractions. Chemical compounds are separated by heating them to a temperature at which one or more fractions of the mixture will vaporize. It uses distillation to ...

through a water-cooled still, by which an alcohol purity of 90% could be obtained. The medicinal properties of ethanol were studied by Arnald of Villanova

Arnaldus de Villa Nova (also called Arnau de Vilanova in Catalan, his language, Arnaldus Villanovanus, Arnaud de Ville-Neuve or Arnaldo de Villanueva, c. 1240–1311) was a physician and a religious reformer. He was also thought to be an alche ...

(1240–1311 CE) and John of Rupescissa (–1366), the latter of whom regarded it as a life-preserving substance able to prevent all diseases (the ''aqua vitae

''Aqua vitae'' (Latin for "water of life") or aqua vita is an archaic name for a concentrated aqueous solution of ethanol. These terms could also be applied to weak ethanol without rectification. Usage was widespread during the Middle Ages an ...

'' or "water of life", also called by John the ''quintessence

Quintessence, or fifth essence, may refer to:

Cosmology

* Aether (classical element), in medieval cosmology and science, the fifth element that fills the universe beyond the terrestrial sphere

* Quintessence (physics), a hypothetical form of da ...

'' of wine).

Nomenclature

Etymology

The word "alcohol" derives from the Arabic '' kohl'' ( ar, الكحل, al-kuḥl), a powder used as an eyeliner. The first part of the word () is the Arabicdefinite article

An article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the" and "a(n)" a ...

, equivalent to ''the'' in English. The second part of the word () has several antecedents in Semitic languages, ultimately deriving from the Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

𒎎𒋆𒁉𒍣𒁕 (guḫlum), meaning stibnite or antimony.

Like its antecedents in Arabic and older languages, the term ''alcohol'' was originally used for the very fine powder produced by the sublimation of the natural mineral stibnite

Stibnite, sometimes called antimonite, is a sulfide mineral with the formula Sb2 S3. This soft grey material crystallizes in an orthorhombic space group. It is the most important source for the metalloid antimony. The name is derived from the ...

to form antimony trisulfide

Antimony trisulfide (Sb2S3) is found in nature as the crystalline mineral stibnite and the amorphous red mineral (actually a mineraloid) metastibnite. It is manufactured for use in safety matches, military ammunition, explosives and fireworks. I ...

. It was considered to be the essence or "spirit" of this mineral. It was used as an antiseptic

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί ''anti'', "against" and σηπτικός ''sēptikos'', "putrefactive") is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putre ...

, eyeliner, and cosmetic

Cosmetic may refer to:

*Cosmetics, or make-up, substances to enhance the beauty of the human body, apart from simple cleaning

*Cosmetic, an adjective describing beauty, aesthetics, or appearance, especially concerning the human body

*Cosmetic, a t ...

. Later the meaning of alcohol was extended to distilled substances in general, and then narrowed again to ethanol, when "spirits" was a synonym for hard liquor

Liquor (or a spirit) is an alcoholic drink produced by distillation of grains, fruits, vegetables, or sugar, that have already gone through alcoholic fermentation. Other terms for liquor include: spirit drink, distilled beverage or hard ...

.

Bartholomew Traheron, in his 1543 translation of John of Vigo

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, introduces the word as a term used by "barbarous" authors for "fine powder." Vigo wrote: "the barbarous auctours use alcohol, or (as I fynde it sometymes wryten) alcofoll, for moost fine poudre."

The 1657 ''Lexicon Chymicum'', by William Johnson glosses the word as "antimonium sive stibium." By extension, the word came to refer to any fluid obtained by distillation, including "alcohol of wine," the distilled essence of wine. Libavius

Andreas Libavius or Andrew Libavius was born in Halle, Germany c. 1550 and died in July 1616. Libavius was a renaissance man who spent time as a professor at the University of Jena teaching history and poetry. After which he became a physician a ...

in ''Alchymia'' (1594) refers to "vini alcohol vel vinum alcalisatum". Johnson (1657) glosses ''alcohol vini'' as "quando omnis superfluitas vini a vino separatur, ita ut accensum ardeat donec totum consumatur, nihilque fæcum aut phlegmatis in fundo remaneat." The word's meaning became restricted to "spirit of wine" (the chemical known today as ethanol) in the 18th century and was extended to the class of substances so-called as "alcohols" in modern chemistry after 1850.

The term ''ethanol'' was invented in 1892, blending " ethane" with the "-ol" ending of "alcohol", which was generalized as a libfix

In linguistics, a libfix is a productive bound morpheme affix created by rebracketing and back-formation, often a generalization of a component of a blended or portmanteau word. For example, ''walkathon'' was coined in 1932 as a blend of ''walk' ...

.

Systematic names

IUPAC nomenclature

A chemical nomenclature is a set of rules to generate systematic names for chemical compounds. The nomenclature used most frequently worldwide is the one created and developed by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

Th ...

is used in scientific publications and where precise identification of the substance is important. In naming simple alcohols, the name of the alkane chain loses the terminal ''e'' and adds the suffix ''-ol'', ''e.g.'', as in "ethanol" from the alkane chain name "ethane". When necessary, the position of the hydroxyl group is indicated by a number between the alkane name and the ''-ol'': propan-1-ol

Propan-1-ol (also propanol, n-propyl alcohol) is a primary alcohol with the formula and sometimes represented as PrOH or ''n''-PrOH. It is a colorless liquid and an isomer of 2-propanol. It is formed naturally in small amounts during many ferme ...

for , propan-2-ol

Isopropyl alcohol (IUPAC name propan-2-ol and also called isopropanol or 2-propanol) is a colorless, flammable organic compound with a pungent alcoholic odor. As an isopropyl group linked to a hydroxyl group (chemical formula ) it is the simple ...

for . If a higher priority group is present (such as an aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl group ...

, ketone, or carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxylic ...

), then the prefix ''hydroxy-''is used, e.g., as in 1-hydroxy-2-propanone (). Compounds having more than one hydroxy group are called polyol

In organic chemistry, a polyol is an organic compound containing multiple hydroxyl groups (). The term "polyol" can have slightly different meanings depending on whether it is used in food science or polymer chemistry. Polyols containing two, thre ...

s. They are named using suffixes -diol, -triol, etc., following a list of the position numbers of the hydroxyl groups, as in propane-1,2-diol for CH3CH(OH)CH2OH (propylene glycol).

In cases where the hydroxy group is bonded to an sp2 carbon on an aromatic ring

In chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property of cyclic ( ring-shaped), ''typically'' planar (flat) molecular structures with pi bonds in resonance (those containing delocalized electrons) that gives increased stability compared to satu ...

, the molecule is classified separately as a phenol and is named using the IUPAC rules for naming phenols. Phenols have distinct properties and are not classified as alcohols.

Common names

In other less formal contexts, an alcohol is often called with the name of the corresponding alkyl group followed by the word "alcohol", e.g.,methyl

In organic chemistry, a methyl group is an alkyl derived from methane, containing one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, having chemical formula . In formulas, the group is often abbreviated as Me. This hydrocarbon group occurs in man ...

alcohol, ethyl alcohol. Propyl alcohol may be ''n''-propyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol, depending on whether the hydroxyl group is bonded to the end or middle carbon on the straight propane chain. As described under systematic naming, if another group on the molecule takes priority, the alcohol moiety is often indicated using the "hydroxy-" prefix.

In archaic nomenclature, alcohols can be named as derivatives of methanol using "-carbinol" as the ending. For instance, can be named trimethylcarbinol.

Primary, secondary, and tertiary

Alcohols are then classified into primary, secondary (''sec-'', ''s-''), and tertiary (''tert-'', ''t-''), based upon the number of carbon atoms connected to the carbon atom that bears the hydroxyl functional group. (The respective numeric shorthands 1°, 2°, and 3° are sometimes used in informal settings.) The primary alcohols have general formulas . The simplest primary alcohol is methanol (), for which R=H, and the next is ethanol, for which , the methyl group. Secondary alcohols are those of the form RR'CHOH, the simplest of which is 2-propanol (). For the tertiary alcohols the general form is RR'R"COH. The simplest example istert-butanol

''tert''-Butyl alcohol is the simplest tertiary alcohol, with a formula of (CH3)3COH (sometimes represented as ''t''-BuOH). Its isomers are 1-butanol, isobutanol, and butan-2-ol. ''tert''-Butyl alcohol is a colorless solid, which melts near r ...

(2-methylpropan-2-ol), for which each of R, R', and R" is . In these shorthands, R, R', and R" represent substituents

A substituent is one or a group of atoms that replaces (one or more) atoms, thereby becoming a moiety in the resultant (new) molecule. (In organic chemistry and biochemistry, the terms ''substituent'' and '' functional group'', as well as '' s ...

, alkyl or other attached, generally organic groups.

Examples

Applications

Alcohols have a long history of myriad uses. For simple mono-alcohols, which is the focus on this article, the following are most important industrial alcohols:.

*methanol, mainly for the production of formaldehyde and as a

Alcohols have a long history of myriad uses. For simple mono-alcohols, which is the focus on this article, the following are most important industrial alcohols:.

*methanol, mainly for the production of formaldehyde and as a fuel additive

Petrol additives increase petrol's octane rating or act as corrosion inhibitors or lubricants, thus allowing the use of higher compression ratios for greater efficiency and power. Types of additives include metal deactivators, corrosion inhibitors, ...

*ethanol, mainly for alcoholic beverages, fuel additive, solvent

*1-propanol, 1-butanol, and isobutyl alcohol for use as a solvent and precursor to solvents

*C6–C11 alcohols used for plasticizers, e.g. in polyvinylchloride

*fatty alcohol (C12–C18), precursors to detergent

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions. There are a large variety of detergents, a common family being the alkylbenzene sulfonates, which are soap-like compounds that are mor ...

s

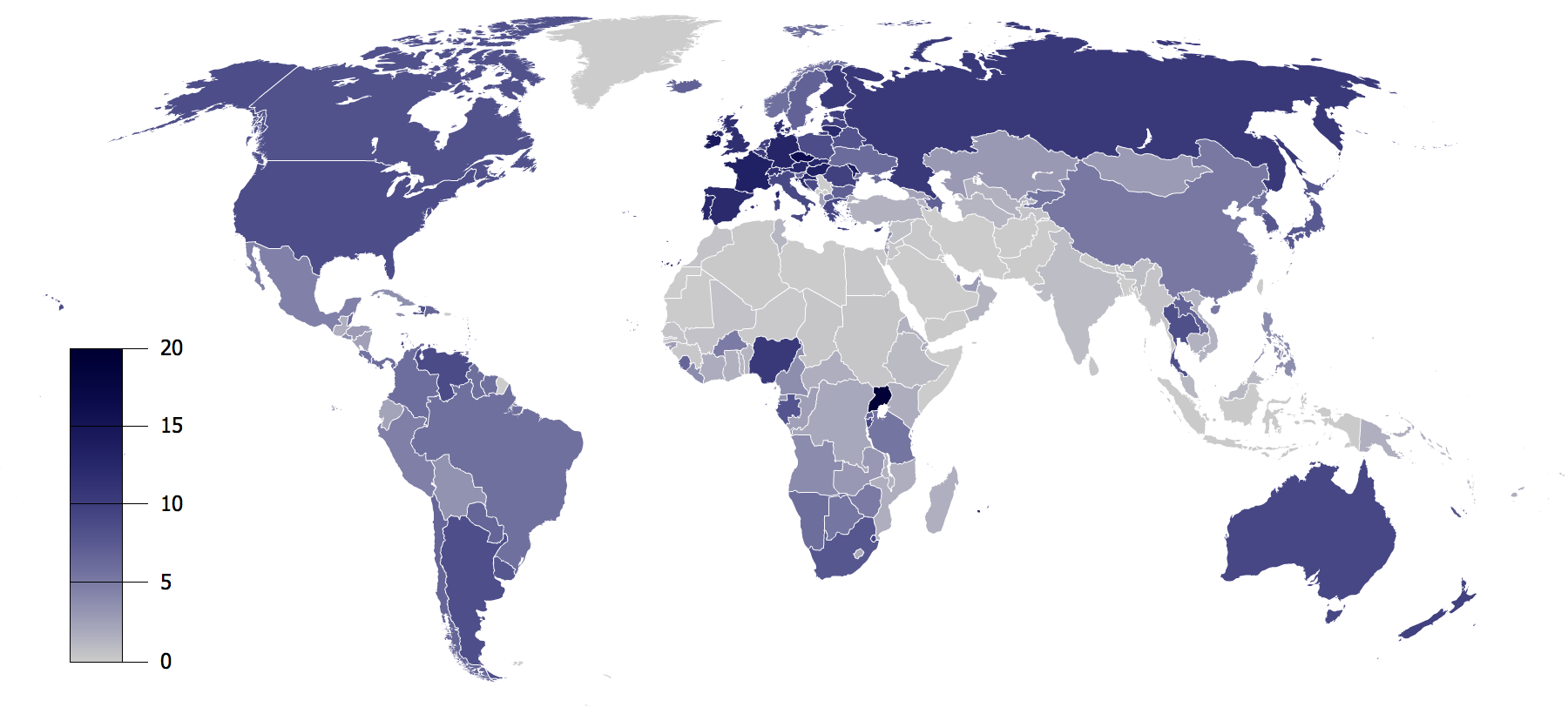

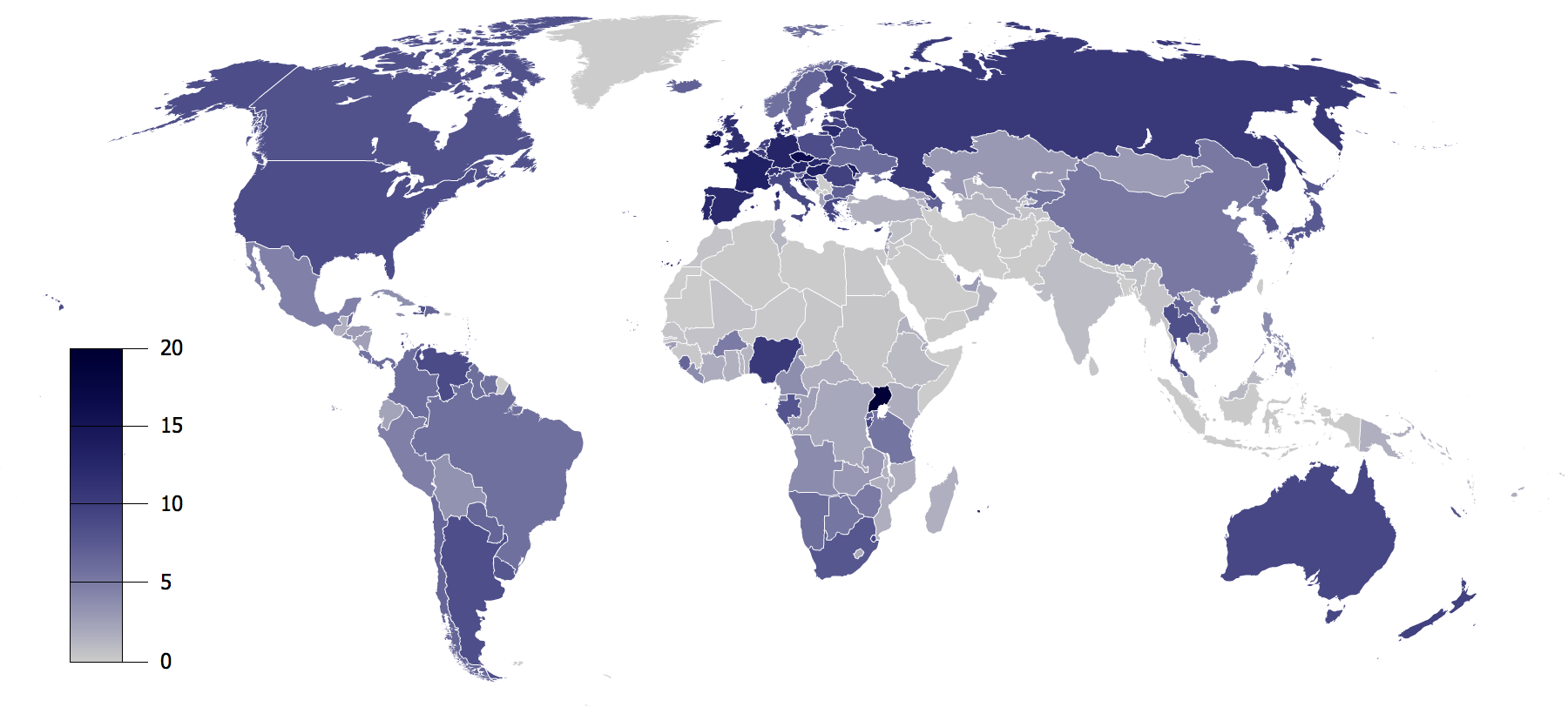

Methanol is the most common industrial alcohol, with about 12 million tons/y produced in 1980. The combined capacity of the other alcohols is about the same, distributed roughly equally.

Toxicity

With respect to acute toxicity, simple alcohols have low acutetoxic

Toxicity is the degree to which a chemical substance or a particular mixture of substances can damage an organism. Toxicity can refer to the effect on a whole organism, such as an animal, bacterium, or plant, as well as the effect on a subs ...

ities. Doses of several milliliters are tolerated. For pentanol

An amyl alcohol is any of eight alcohols with the formula C5H12O. A mixture of amyl alcohols (also called amyl alcohol) can be obtained from fusel alcohol. Amyl alcohol is used as a solvent and in esterification, by which is produced amyl acetat ...

s, hexanol

Hexanol may refer to any of the following isomeric organic compounds with the formula C6H13OH:

:

See also

* Cyclohexanol

* Amyl alcohol

An amyl alcohol is any of eight alcohols with the formula C5H12O. A mixture of amyl alcohols (also called a ...

s, octanol

Octanols are alcohols with the formula C8H17OH. A simple and important member is 1-octanol, with an unbranched chain of carbons. Other commercially important octanols are 2-octanol and 2-ethylhexanol.

There are 89 possible isomers

In che ...

s and longer alcohols, LD50 range from 2–5 g/kg (rats, oral). Ethanol is less acutely toxic. All alcohols are mild skin irritants.

The metabolism of methanol (and ethylene glycol

Ethylene glycol ( IUPAC name: ethane-1,2-diol) is an organic compound (a vicinal diol) with the formula . It is mainly used for two purposes, as a raw material in the manufacture of polyester fibers and for antifreeze formulations. It is an odo ...

) is affected by the presence of ethanol, which has a higher affinity for liver alcohol dehydrogenase

Alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH) () are a group of dehydrogenase enzymes that occur in many organisms and facilitate the interconversion between alcohols and aldehydes or ketones with the reduction of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to NADH ...

. In this way methanol will be excreted intact in urine.

Physical properties

In general, the hydroxyl group makes alcohols polar. Those groups can form hydrogen bonds to one another and to most other compounds. Owing to the presence of the polar OH alcohols are more water-soluble than simple hydrocarbons. Methanol, ethanol, and propanol are miscible in water. Butanol, with a four-carbon chain, is moderately soluble. Because of hydrogen bonding, alcohols tend to have higher boiling points than comparable hydrocarbons andether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. They have the general formula , where R and R′ represent the alkyl or aryl groups. Ethers can again b ...

s. The boiling point of the alcohol ethanol is 78.29 °C, compared to 69 °C for the hydrocarbon hexane

Hexane () is an organic compound, a straight-chain alkane with six carbon atoms and has the molecular formula C6H14.

It is a colorless liquid, odorless when pure, and with boiling points approximately . It is widely used as a cheap, relatively ...

, and 34.6 °C for diethyl ether.

Occurrence in nature

Simple alcohols are found widely in nature. Ethanol is the most prominent because it is the product of fermentation, a major energy-producing pathway. Other simple alcohols, chieflyfusel alcohols

Fusel alcohols or fuselol, also sometimes called fusel oils in Europe, are mixtures of several higher alcohols (those with more than two carbons, chiefly amyl alcohol) produced as a by-product of alcoholic fermentation. The word ''Fusel'' is Ger ...

, are formed in only trace amounts. More complex alcohols however are pervasive, as manifested in sugars, some amino acids, and fatty acids.

Production

Ziegler and oxo processes

In theZiegler process In organic chemistry, the Ziegler process (also called the Ziegler-Alfol synthesis) is a method for producing fatty alcohols from ethylene using an organoaluminium compound. The reaction produces linear primary alcohols with an even numbered carbon ...

, linear alcohols are produced from ethylene and triethylaluminium followed by oxidation and hydrolysis. An idealized synthesis of 1-octanol

1-Octanol, also known as octan-1-ol, is the organic compound with the molecular formula CH3(CH2)7OH. It is a fatty alcohol. Many other isomers are also known generically as octanols. 1-Octanol is manufactured for the synthesis of esters for use ...

is shown:

:fatty alcohol

Fatty alcohols (or long-chain alcohols) are usually high-molecular-weight, straight-chain primary alcohols, but can also range from as few as 4–6 carbons to as many as 22–26, derived from natural fats and oils. The precise chain length varies ...

s, which are useful for detergents.

Hydration reactions

Some low molecular weight alcohols of industrial importance are produced by the addition of water to alkenes. Ethanol, isopropanol, 2-butanol, and tert-butanol are produced by this general method. Two implementations are employed, the direct and indirect methods. The direct method avoids the formation of stable intermediates, typically using acid catalysts. In the indirect method, the alkene is converted to the sulfate ester, which is subsequently hydrolyzed. The directhydration Hydration may refer to:

* Hydrate, a substance that contains water

* Hydration enthalpy, energy released through hydrating a substance

* Hydration reaction, a chemical addition reaction where a hydroxyl group and proton are added to a compound

* ...

using ethylene

Ethylene ( IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon-carbon double bonds).

Ethylene ...

( ethylene hydration) or other alkenes from cracking of fractions of distilled crude oil.

Hydration is also used industrially to produce the diol ethylene glycol

Ethylene glycol ( IUPAC name: ethane-1,2-diol) is an organic compound (a vicinal diol) with the formula . It is mainly used for two purposes, as a raw material in the manufacture of polyester fibers and for antifreeze formulations. It is an odo ...

from ethylene oxide

Ethylene oxide is an organic compound with the formula . It is a cyclic ether and the simplest epoxide: a three-membered ring consisting of one oxygen atom and two carbon atoms. Ethylene oxide is a colorless and flammable gas with a faintly sw ...

.

Biological routes

Ethanol is obtained by fermentation using glucose produced from sugar from the hydrolysis of starch, in the presence of yeast and temperature of less than 37 °C to produce ethanol. For instance, such a process might proceed by the conversion of sucrose by the enzyme invertase into glucose andfructose

Fructose, or fruit sugar, is a ketonic simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galactose, that are absorbe ...

, then the conversion of glucose by the enzyme complex zymase

Zymase is an enzyme complex that catalyzes the fermentation of sugar into ethanol and carbon dioxide. It occurs naturally in yeasts. Zymase activity varies among yeast strains.

Zymase is also the brand name of the drug pancrelipase.

Cell-free ...

into ethanol and carbon dioxide.

Several species of the benign bacteria in the intestine use fermentation as a form of anaerobic metabolism

Anaerobic respiration is respiration using electron acceptors other than molecular oxygen (O2). Although oxygen is not the final electron acceptor, the process still uses a respiratory electron transport chain.

In aerobic organisms undergoing re ...

. This metabolic reaction produces ethanol as a waste product. Thus, human bodies contain some quantity of alcohol endogenously produced by these bacteria. In rare cases, this can be sufficient to cause " auto-brewery syndrome" in which intoxicating quantities of alcohol are produced.

Like ethanol, butanol can be produced by fermentation processes. ''Saccharomyces'' yeast are known to produce these higher alcohols at temperatures above . The bacterium ''Clostridium acetobutylicum

''Clostridium acetobutylicum'', ATCC 824, is a commercially valuable bacterium sometimes called the "Weizmann Organism", after Jewish Russian-born biochemist Chaim Weizmann. A senior lecturer at the University of Manchester, England, he used t ...

'' can feed on cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

to produce butanol on an industrial scale.

Substitution

Primaryalkyl halide

The haloalkanes (also known as halogenoalkanes or alkyl halides) are alkanes containing one or more halogen substituents. They are a subset of the general class of halocarbons, although the distinction is not often made. Haloalkanes are widely us ...

s react with aqueous NaOH

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula NaOH. It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly caustic base and alkali t ...

or KOH mainly to primary alcohols in nucleophilic aliphatic substitution

In chemistry, a nucleophilic substitution is a class of chemical reactions in which an electron-rich chemical species (known as a nucleophile) replaces a functional group within another electron-deficient molecule (known as the electrophile). The ...

. (Secondary and especially tertiary alkyl halides will give the elimination (alkene) product instead). Grignard reagents react with carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups. A compound containing a ...

groups to secondary and tertiary alcohols. Related reactions are the Barbier reaction

The Barbier reaction is an organometallic reaction between an alkyl halide (chloride, bromide, iodide), a carbonyl group and a metal. The reaction can be performed using magnesium, aluminium, zinc, indium, tin, samarium, barium or their salts. Th ...

and the Nozaki-Hiyama reaction.

Reduction

Aldehydes

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl group ...

or ketones are reduced with sodium borohydride or lithium aluminium hydride (after an acidic workup). Another reduction by aluminiumisopropylates is the Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction. Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation

In chemistry, the Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation refers to methodology for enantioselective reduction of ketones and related functional groups. This methodology was introduced by Ryoji Noyori, who shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2001 for c ...

is the asymmetric reduction of β-keto-esters.

Hydrolysis

Alkenes

In organic chemistry, an alkene is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond.

Alkene is often used as synonym of olefin, that is, any hydrocarbon containing one or more double bonds.H. Stephen Stoker (2015): General, Organic, an ...

engage in an acid catalysed hydration reaction

In chemistry, a hydration reaction is a chemical reaction in which a substance combines with water. In organic chemistry, water is added to an unsaturated substrate, which is usually an alkene or an alkyne. This type of reaction is employed industr ...

using concentrated sulfuric acid as a catalyst that gives usually secondary or tertiary alcohols. Formation of a secondary alcohol via alkene reduction and hydration is shown on the right:

:oxymercuration-reduction

The oxymercuration reaction is an electrophilic addition organic reaction that transforms an alkene into a neutral alcohol. In oxymercuration, the alkene reacts with mercuric acetate (AcO–Hg–OAc) in aqueous solution to yield the addition of a ...

of alkenes are more reliable in organic synthesis. Alkenes react with N-bromosuccinimide

''N''-Bromosuccinimide or NBS is a chemical reagent used in radical substitution, electrophilic addition, and electrophilic substitution reactions in organic chemistry. NBS can be a convenient source of Br•, the bromine radical.

Preparation ...

and water in halohydrin formation reaction. Amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are compounds and functional groups that contain a basic nitrogen atom with a lone pair. Amines are formally derivatives of ammonia (), wherein one or more hydrogen atoms have been replaced by a substituent suc ...

s can be converted to diazonium salt

Diazonium compounds or diazonium salts are a group of organic compounds sharing a common functional group where R can be any organic group, such as an alkyl or an aryl, and X is an inorganic or organic anion, such as a halide.

General prope ...

s, which are then hydrolyzed.

Reactions

Deprotonation

With aqueous p''K''a values of around 16–19, they are, in general, slightly weakeracid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

s than water. With strong bases such as sodium hydride or sodium they form salts called ''alkoxide

In chemistry, an alkoxide is the conjugate base of an alcohol and therefore consists of an organic group bonded to a negatively charged oxygen atom. They are written as , where R is the organic substituent. Alkoxides are strong bases and, wh ...

s'', with the general formula (where R is an alkyl

In organic chemistry, an alkyl group is an alkane missing one hydrogen.

The term ''alkyl'' is intentionally unspecific to include many possible substitutions.

An acyclic alkyl has the general formula of . A cycloalkyl is derived from a cycloal ...

and M is a metal

A metal (from Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typica ...

).

: Williamson ether synthesis

The Williamson ether synthesis is an organic reaction, forming an ether from an organohalide and a deprotonated alcohol (alkoxide). This reaction was developed by Alexander Williamson in 1850. Typically it involves the reaction of an alkoxide io ...

) in this solvent. In particular, or in DMSO can be used to generate significant equilibrium concentrations of acetylide ions through the deprotonation of alkynes (see Favorskii reaction

The Favorskii reaction is an organic chemistry reaction between an alkyne and a carbonyl group, under basic conditions. The reaction was discovered in the early 1900s by the Russian chemist Alexei Yevgrafovich Favorskii.

When the carbonyl is a ...

).

Nucleophilic substitution

The OH group is not a good leaving group innucleophilic substitution

In chemistry, a nucleophilic substitution is a class of chemical reactions in which an electron-rich chemical species (known as a nucleophile) replaces a functional group within another electron-deficient molecule (known as the electrophile). Th ...

reactions, so neutral alcohols do not react in such reactions. However, if the oxygen is first protonated

In chemistry, protonation (or hydronation) is the adding of a proton (or hydron, or hydrogen cation), (H+) to an atom, molecule, or ion, forming a conjugate acid. (The complementary process, when a proton is removed from a Brønsted–Lowry acid, i ...

to give , the leaving group ( water) is much more stable, and the nucleophilic substitution can take place. For instance, tertiary alcohols react with hydrochloric acid to produce tertiary alkyl halide

The haloalkanes (also known as halogenoalkanes or alkyl halides) are alkanes containing one or more halogen substituents. They are a subset of the general class of halocarbons, although the distinction is not often made. Haloalkanes are widely us ...

s, where the hydroxyl group is replaced by a chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between them. Chlorine is ...

atom by unimolecular nucleophilic substitution

The SN1 reaction is a substitution reaction in organic chemistry, the name of which refers to the Hughes-Ingold symbol of the mechanism. "SN" stands for "nucleophilic substitution", and the "1" says that the rate-determining step is unimolecular ...

. If primary or secondary alcohols are to be reacted with hydrochloric acid, an activator such as zinc chloride is needed. In alternative fashion, the conversion may be performed directly using thionyl chloride.

hydrobromic acid

Hydrobromic acid is a strong acid formed by dissolving the diatomic molecule hydrogen bromide (HBr) in water. "Constant boiling" hydrobromic acid is an aqueous solution that distills at and contains 47.6% HBr by mass, which is 8.77 mol/L. H ...

or phosphorus tribromide, for example:

: alkane

In organic chemistry, an alkane, or paraffin (a historical trivial name that also has other meanings), is an acyclic saturated hydrocarbon. In other words, an alkane consists of hydrogen and carbon atoms arranged in a tree structure in whi ...

with tributyltin hydride or a trimethylborane-water complex in a radical substitution reaction.

Dehydration

Meanwhile, the oxygen atom haslone pair

In chemistry, a lone pair refers to a pair of valence electrons that are not shared with another atom in a covalent bondIUPAC ''Gold Book'' definition''lone (electron) pair''/ref> and is sometimes called an unshared pair or non-bonding pair. Lone ...

s of nonbonded electrons that render it weakly basic

BASIC (Beginners' All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) is a family of general-purpose, high-level programming languages designed for ease of use. The original version was created by John G. Kemeny and Thomas E. Kurtz at Dartmouth College i ...

in the presence of strong acids such as sulfuric acid. For example, with methanol:

elimination reaction

An elimination reaction is a type of organic reaction in which two substituents are removed from a molecule in either a one- or two-step mechanism. The one-step mechanism is known as the E2 reaction, and the two-step mechanism is known as the E1 r ...

to produce alkene

In organic chemistry, an alkene is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond.

Alkene is often used as synonym of olefin, that is, any hydrocarbon containing one or more double bonds.H. Stephen Stoker (2015): General, Organic, a ...

s. The reaction, in general, obeys Zaitsev's Rule

In organic chemistry, Zaitsev's rule (or Saytzeff's rule, Saytzev's rule) is an empirical rule for predicting the favored alkene product(s) in elimination reactions. While at the University of Kazan, Russian chemist Alexander Zaitsev studied a va ...

, which states that the most stable (usually the most substituted) alkene is formed. Tertiary alcohols eliminate easily at just above room temperature, but primary alcohols require a higher temperature.

This is a diagram of acid catalysed dehydration of ethanol to produce ethylene

Ethylene ( IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon-carbon double bonds).

Ethylene ...

:

A more controlled elimination reaction requires the formation of the xanthate ester.

A more controlled elimination reaction requires the formation of the xanthate ester.

Protonolysis

Tertiary alcohols react with strong acids to generate carbocations. The reaction is related to their dehydration, e.g. isobutylene from tert-butyl alcohol. A special kind of dehydration reaction involvestriphenylmethanol

Triphenylmethanol (also known as triphenylcarbinol, TrOH) is an organic compound. It is a white crystalline solid that is insoluble in water and petroleum ether, but well soluble in ethanol, diethyl ether, and benzene. In strongly acidic solutions ...

and especially its amine-substituted derivatives. When treated with acid, these alcohols lose water to give stable carbocations, which are commercial dyes.

322px, Preparation of crystal violet by protonolysis of the tertiary alcohol.

Esterification

Alcohol andcarboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxylic ...

s react in the so-called Fischer esterification

Fischer is a German occupational surname, meaning fisherman. The name Fischer is the fourth most common German surname. The English version is Fisher.

People with the surname A

* Abraham Fischer (1850–1913) South African public official

* ...

. The reaction usually requires a catalyst

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the reaction rate, rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the ...

, such as concentrated sulfuric acid:

: Oxidation

Primary alcohols () can be oxidized either toaldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl group ...

s () or to carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxylic ...

s (). The oxidation of secondary alcohols () normally terminates at the ketone () stage. Tertiary alcohols () are resistant to oxidation.

The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids

The oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids is an important oxidation reaction in organic chemistry.

When a primary alcohol is converted to a carboxylic acid, the terminal carbon atom increases its oxidation state by four. Oxidants able ...

normally proceeds via the corresponding aldehyde, which is transformed via an ''aldehyde hydrate'' () by reaction with water before it can be further oxidized to the carboxylic acid.

Reagents useful for the transformation of primary alcohols to aldehydes are normally also suitable for the

Reagents useful for the transformation of primary alcohols to aldehydes are normally also suitable for the oxidation of secondary alcohols to ketones

The oxidation of secondary alcohols to ketones is an important oxidation reaction in organic chemistry.

When a secondary alcohol is oxidised, it is converted to a ketone. The hydrogen from the hydroxyl group is lost along with the hydrogen bond ...

. These include Collins reagent

Collins reagent is the complex of chromium(VI) oxide with pyridine in dichloromethane. This metal-pyridine complex, a red solid, is used to oxidize primary alcohols to the corresponding aldehydes and secondary alcohols to the corresponding ket ...

and Dess-Martin periodinane. The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids can be carried out using potassium permanganate or the Jones reagent

Jones may refer to:

People

*Jones (surname), a common Welsh and English surname

* List of people with surname Jones

*Jones (singer), a British singer-songwriter

Arts and entertainment

* Jones (''Animal Farm''), a human character in George Orwell ...

.

See also

*Enol

In organic chemistry, alkenols (shortened to enols) are a type of reactive structure or intermediate in organic chemistry that is represented as an alkene (olefin) with a hydroxyl group attached to one end of the alkene double bond (). The ter ...

* Ethanol fuel

* Fatty alcohol

Fatty alcohols (or long-chain alcohols) are usually high-molecular-weight, straight-chain primary alcohols, but can also range from as few as 4–6 carbons to as many as 22–26, derived from natural fats and oils. The precise chain length varies ...

* Index of alcohol-related articles

* List of alcohols

* Lucas test

* Polyol

In organic chemistry, a polyol is an organic compound containing multiple hydroxyl groups (). The term "polyol" can have slightly different meanings depending on whether it is used in food science or polymer chemistry. Polyols containing two, thre ...

* Rubbing alcohol

Rubbing alcohol is either an isopropyl alcohol or an ethanol-based liquid, with isopropyl alcohol products being the most widely available. The comparable ''British Pharmacopoeia'' (''BP'') is surgical spirit. Rubbing alcohol is denatured and un ...

* Sugar alcohol

Sugar alcohols (also called polyhydric alcohols, polyalcohols, alditols or glycitols) are organic compounds, typically derived from sugars, containing one hydroxyl group (–OH) attached to each carbon atom. They are white, water-soluble solid ...

* Transesterification

Notes

Citations

General references

* {{Authority control Antiseptics Functional groups