Toni Morrison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

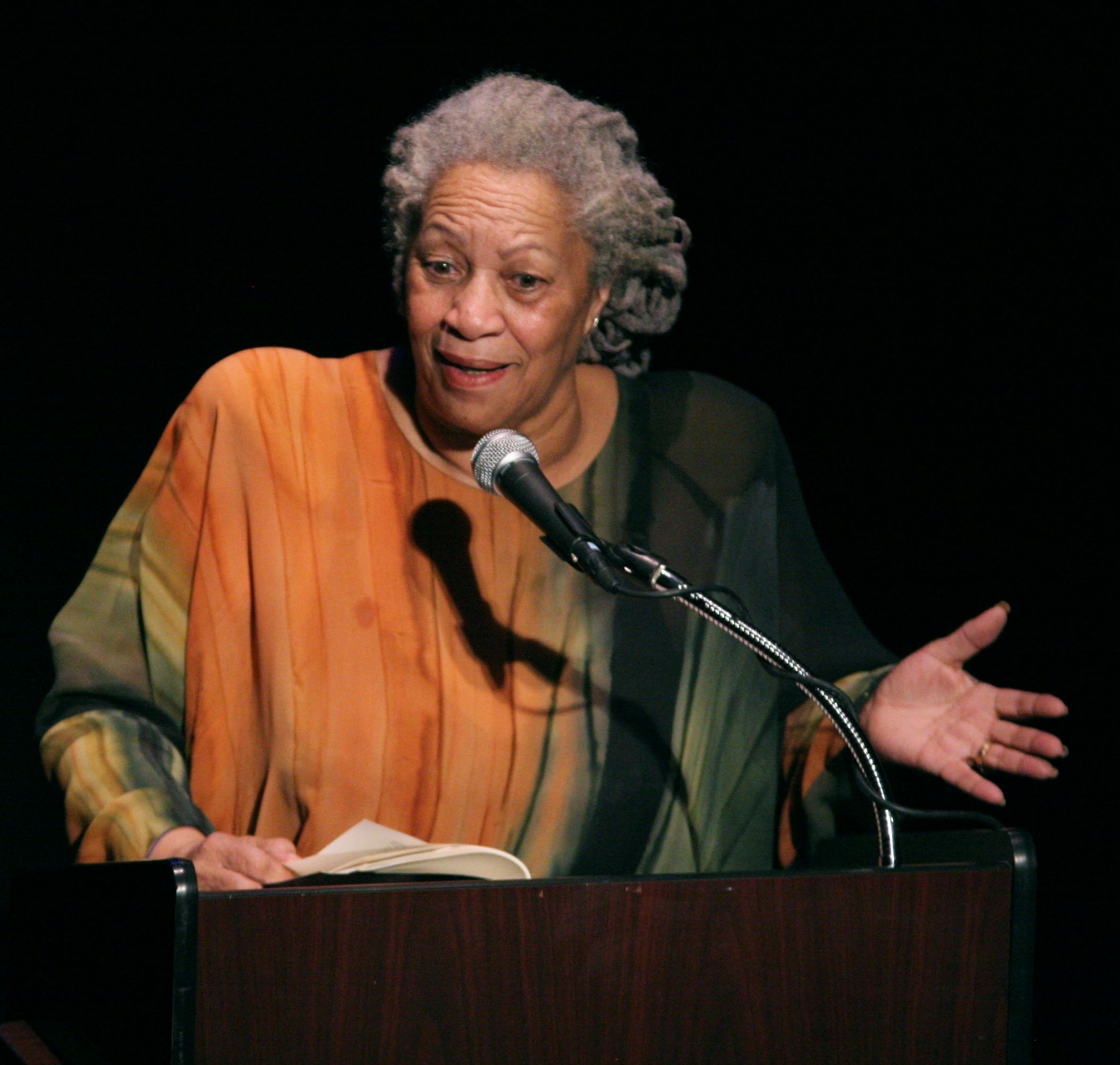

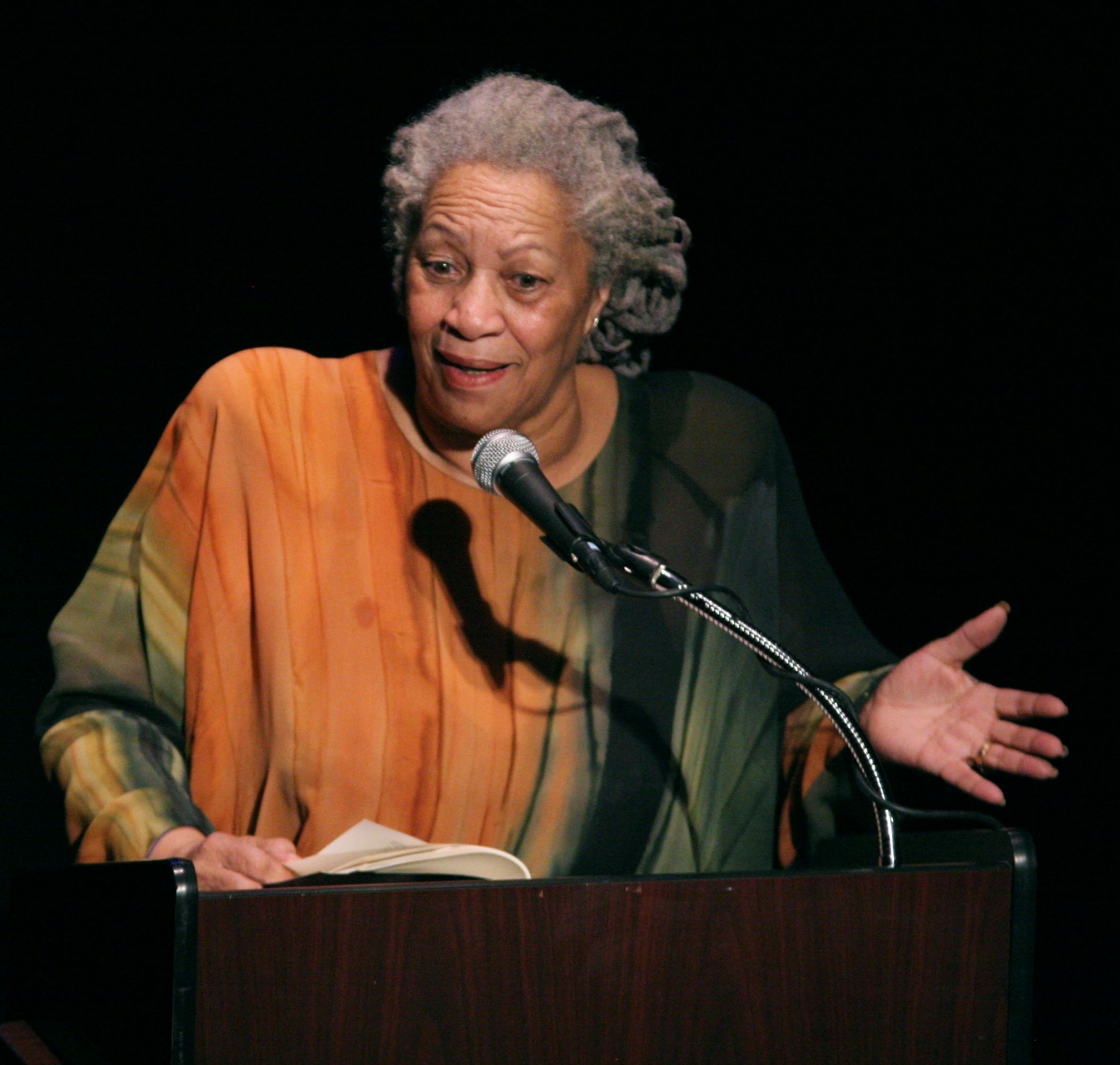

Chloe Anthony Wofford Morrison (born Chloe Ardelia Wofford; February 18, 1931 – August 5, 2019), known as Toni Morrison, was an American novelist and editor. Her first novel, '' The Bluest Eye'', was published in 1970. The critically acclaimed ''

Bio.com, April 2, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2015. In that capacity, Morrison played a vital role in bringing Black literature into the mainstream. One of the first books she worked on was the groundbreaking ''Contemporary African Literature'' (1972), a collection that included work by Nigerian writers

In 1987, Morrison published her most celebrated novel, '' Beloved''. It was inspired by the true story of an enslaved African-American woman, Margaret Garner, whose story Morrison had discovered when compiling ''The Black Book''. Garner had escaped slavery but was pursued by slave hunters. Facing a return to slavery, Garner killed her two-year-old daughter but was captured before she could kill herself. Morrison's novel imagines the dead baby returning as a ghost, Beloved, to haunt her mother and family.

''Beloved'' was a critical success and a bestseller for 25 weeks. ''

In 1987, Morrison published her most celebrated novel, '' Beloved''. It was inspired by the true story of an enslaved African-American woman, Margaret Garner, whose story Morrison had discovered when compiling ''The Black Book''. Garner had escaped slavery but was pursued by slave hunters. Facing a return to slavery, Garner killed her two-year-old daughter but was captured before she could kill herself. Morrison's novel imagines the dead baby returning as a ghost, Beloved, to haunt her mother and family.

''Beloved'' was a critical success and a bestseller for 25 weeks. ''

at NEH Website. Retrieved January 22, 2009. Morrison's lecture, entitled "The Future of Time: Literature and Diminished Expectations", began with the aphorism: "Time, it seems, has no future." She cautioned against the misuse of history to diminish expectations of the future. Morrison was also honored with the 1996 National Book Foundation's Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, which is awarded to a writer "who has enriched our literary heritage over a life of service, or a corpus of work". The third novel of her ''Beloved'' Trilogy, ''

Michigan Opera Theater, April 1, 2005. . ''

Inspired by her curatorship at the Louvre Museum, Morrison returned to Princeton in the fall 2008 to lead a small seminar, also entitled "The Foreigner's Home".

On November 17, 2017, Princeton University dedicated Morrison Hall (a building previously called West College) in her honor.

Inspired by her curatorship at the Louvre Museum, Morrison returned to Princeton in the fall 2008 to lead a small seminar, also entitled "The Foreigner's Home".

On November 17, 2017, Princeton University dedicated Morrison Hall (a building previously called West College) in her honor.

In 2011, Morrison worked with opera director

In 2011, Morrison worked with opera director

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in

Toni Morrison Elementary School

opened in her hometown of Lorain, Ohio. In 2019, a resolution was passed in her hometown of

"Toni Morrison: Beloved"

From the ''Bookworm'' archives, August 15, 2019.

Bookworm

Interviews (Audio) with Michael Silverblatt * * * * *

"Reading the Writing: A Conversation with Toni Morrison"

(Cornell University video, March 7, 2013) * *

Toni Morrison's oral history video excerpts

at The National Visionary Leadership Project

a

Princeton University Library Special Collections

Toni Morrison Society

based at

Song of Solomon

The Song of Songs (), also called the Canticle of Canticles or the Song of Solomon, is a biblical poem, one of the five ("scrolls") in the ('writings'), the last section of the Tanakh. Unlike other books in the Hebrew Bible, it is erotic poe ...

'' (1977) brought her national attention and won the National Book Critics Circle Award

The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English".Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

for '' Beloved'' (1987); she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1993.

Born and raised in Lorain, Ohio

Lorain () is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. It is located in Northeast Ohio on Lake Erie, at the mouth of the Black River (Ohio), Black River about west of Cleveland. It is the List of cities in Ohio, ninth-most populous city in O ...

, Morrison graduated from Howard University

Howard University is a private, historically black, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and accredited by the Mid ...

in 1953 with a B.A. in English. Morrison earned a master's degree in American Literature from Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

in 1955. In 1957 she returned to Howard University, was married, and had two children before divorcing in 1964. Morrison became the first Black female editor for fiction at Random House

Random House is an imprint and publishing group of Penguin Random House. Founded in 1927 by businessmen Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer as an imprint of Modern Library, it quickly overtook Modern Library as the parent imprint. Over the foll ...

in New York City in the late 1960s. She developed her own reputation as an author in the 1970s and '80s. Her novel ''Beloved'' was made into a film

A film, also known as a movie or motion picture, is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, emotions, or atmosphere through the use of moving images that are generally, sinc ...

in 1998. Morrison's works are praised for addressing the harsh consequences of racism in the United States

Racism has been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices, and actions (including violence) against Race (human categorization), racial or ethnic groups throughout the history of the United States. Since the early Colonial history of the Uni ...

and the Black American experience.

The National Endowment for the Humanities

The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) is an independent federal agency of the U.S. government, established by thNational Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965(), dedicated to supporting research, education, preserv ...

selected Morrison for the Jefferson Lecture

The Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities is an honorary lecture series established in 1972 by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). According to the NEH, the Lecture is "the highest honor the federal government confers for distinguished ...

, the U.S. federal government's highest honor for achievement in the humanities, in 1996. She was honored with the National Book Foundation

The National Book Foundation (NBF) is an American nonprofit organization established with the goal "to raise the cultural appreciation of great writing in America." Established in 1989 by National Book Awards, Inc.,Edwin McDowell. "Book Notes: ...

's Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters the same year. President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

presented her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by decision of the president of the United States to "any person recommended to the President ...

on May 29, 2012. She received the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction The PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction is awarded by PEN America

PEN America (formerly PEN American Center), founded in 1922, and headquartered in New York City, is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization whose goal is to rais ...

in 2016. Morrison was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame

The National Women's Hall of Fame (NWHF) is an American institution founded to honor and recognize women. It was incorporated in 1969 in Seneca Falls, New York, and first inducted honorees in 1973. As of 2024, the Hall has honored 312 inducte ...

in 2020.

Early years

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford, the second of four children from a working-class, Black family, inLorain, Ohio

Lorain () is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. It is located in Northeast Ohio on Lake Erie, at the mouth of the Black River (Ohio), Black River about west of Cleveland. It is the List of cities in Ohio, ninth-most populous city in O ...

, to Ramah (née Willis) and George Wofford. Her mother was born in Greenville, Alabama

Greenville is a city in and the county seat of Butler County, Alabama, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 7,374. Greenville is known as the Camellia City, wherein originated the movement to change t ...

, and moved north with her family as a child. She was a homemaker and a devout member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Methodist denomination based in the United States. It adheres to Wesleyan theology, Wesleyan–Arminian theology and has a connexionalism, connexional polity. It ...

. George Wofford grew up in Cartersville, Georgia

Cartersville is a city in and the county seat of Bartow County, Georgia, Bartow County, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States; it is located within the northwest edge of the Atlanta metropolitan area. As of the 2020 United States Census, ...

. When Wofford was about 15 years old, a group of white people lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of in ...

two African-American businessmen who lived on his street. Morrison later said: "He never told us that he'd seen bodies. But he had seen them. And that was too traumatic, I think, for him." Soon after the lynching, George Wofford moved to the racially integrated town of Lorain, Ohio, in the hope of escaping racism and securing gainful employment in Ohio's burgeoning industrial economy. He worked odd jobs and as a welder for U.S. Steel. In a 2015 interview Morrison said that her father, traumatized by his experiences of racism, hated whites so much he would not let them in the house.

When Morrison was about two years old, her family's landlord set fire to the house in which they lived, while they were home, because her parents could not afford to pay rent. Her family responded to what she called this "bizarre form of evil" by laughing at the landlord rather than falling into despair. Morrison later said her family's response demonstrated how to keep your integrity and claim your own life in the face of acts of such "monumental crudeness".

Morrison's parents instilled in her a sense of heritage and language through telling traditional African-American folktales, ghost stories, and singing songs. She read frequently as a child; among her favorite authors were Jane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

and Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

.

Morrison became a Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

at the age of 12 and took the baptismal name

A Christian name, sometimes referred to as a baptismal name, is a religious name, religious personal personal name, name given on the occasion of a Christian baptism, though now most often given by parents at birth. In Anglosphere, English-spe ...

Anthony (after Anthony of Padua

Anthony of Padua, Order of Friars Minor, OFM, (; ; ) or Anthony of Lisbon (; ; ; born Fernando Martins de Bulhões; 15 August 1195 – 13 June 1231) was a Portuguese people, Portuguese Catholic priest and member of the Order of Friars Minor.

...

), which led to her nickname, Toni. Attending Lorain High School, she was on the debate team, the yearbook staff, and in the drama club.

Career

Adulthood, Howard and Cornell years, and editing career: 1949–1975

In 1949, she enrolled atHoward University

Howard University is a private, historically black, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and accredited by the Mid ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, seeking the company of fellow Black intellectuals. She was the first person in her family to attend college, meaning that she was a first-generation college student. Initially a student in the drama program at Howard, she studied theatre with celebrated drama teachers Anne Cooke Reid and Owen Dodson. It was while at Howard that she encountered racially segregated restaurants and buses for the first time. She graduated in 1953 with a B.A. in English and a minor in Classics, and was able to work with key members of the Harlem Renaissance era such as Alain Locke

Alain LeRoy Locke (September 13, 1885 – June 9, 1954) was an American writer, philosopher, and educator. Distinguished in 1907 as the first African American Rhodes Scholar, Locke became known as the philosophical architect—the acknowledged " ...

and Sterling Brown. Additionally, she participated in the university's theater group, known as the Howard Players, where she had the opportunity to travel the Deep South, which was a defining experience of her life.

Morrison went on to earn a Master of Arts degree in 1955 from Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

in Ithaca, New York. Her master's thesis was titled "Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer and one of the most influential 20th-century modernist authors. She helped to pioneer the use of stream of consciousness narration as a literary device.

Vir ...

's and William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer. He is best known for William Faulkner bibliography, his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, a stand-in fo ...

's treatment of the alienated". She taught English, first at Texas Southern University

Texas Southern University (Texas Southern or TSU) is a Public university, public Historically black colleges and universities, historically Black university in Houston. The university is a member school of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund an ...

in Houston

Houston ( ) is the List of cities in Texas by population, most populous city in the U.S. state of Texas and in the Southern United States. Located in Southeast Texas near Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico, it is the county seat, seat of ...

from 1955 to 1957, and then at Howard University for the next seven years. While teaching at Howard, she met Harold Morrison, a Jamaican architect, whom she married in 1958. Their first son was born in 1961 and she was pregnant with their second son when she and Harold divorced in 1964.

After her divorce and the birth of her son Slade in 1965, Morrison began working as an editor for L. W. Singer, a textbook division of publisher Random House

Random House is an imprint and publishing group of Penguin Random House. Founded in 1927 by businessmen Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer as an imprint of Modern Library, it quickly overtook Modern Library as the parent imprint. Over the foll ...

, in Syracuse, New York. Two years later, she transferred to Random House in New York City, where she became their first Black woman senior editor in the fiction department."Toni Morrison Biography"Bio.com, April 2, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2015. In that capacity, Morrison played a vital role in bringing Black literature into the mainstream. One of the first books she worked on was the groundbreaking ''Contemporary African Literature'' (1972), a collection that included work by Nigerian writers

Wole Soyinka

Wole Soyinka , (born 13 July 1934) is a Nigerian author, best known as a playwright and poet. He has written three novels, ten collections of short stories, seven poetry collections, twenty five plays and five memoirs. He also wrote two transla ...

, Chinua Achebe

Chinua Achebe (; born Albert Chinụalụmọgụ Achebe; 16 November 1930 – 21 March 2013) was a Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic who is regarded as a central figure of modern African literature. His first novel ''Things Fall Apart'' ( ...

, and South African playwright Athol Fugard

Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard (; 11 June 19328 March 2025) was a South African playwright, novelist, actor and director. Widely regarded as South Africa's greatest playwright and acclaimed as "the greatest active playwright in the English-speaki ...

. She fostered a new generation of Afro-American writers, including poet and novelist Toni Cade Bambara

Toni Cade Bambara, born Miltona Mirkin Cade (March 25, 1939 – December 9, 1995), was an African-American author, documentary film-maker, social activist and college professor.

Early life and education

Miltona Mirkin Cade was born in Harlem, ...

, radical activist Angela Davis

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American Marxist and feminist political activist, philosopher, academic, and author. She is Distinguished Professor Emerita of Feminist Studies and History of Consciousness at the University of ...

, Black Panther

A black panther is the Melanism, melanistic colour variant of the leopard (''Panthera pardus'') and the jaguar (''Panthera onca''). Black panthers of both species have excess black pigments, but their typical Rosette (zoology), rosettes are al ...

Huey Newton and novelist Gayl Jones, whose writing Morrison discovered. She also brought to publication the 1975 autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life, providing a personal narrative that reflects on the author's experiences, memories, and insights. This genre allows individuals to share thei ...

of the outspoken boxing champion Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and social activist. A global cultural icon, widely known by the nickname "The Greatest", he is often regarded as the gr ...

, '' The Greatest: My Own Story''. In addition, she published and promoted the work of Henry Dumas, a little-known novelist and poet who in 1968 had been shot to death by a transit officer in the New York City Subway

The New York City Subway is a rapid transit system in New York City serving the New York City boroughs, boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. It is owned by the government of New York City and leased to the New York City Tr ...

.

Among other books that Morrison developed and edited is '' The Black Book'' (1974), an anthology of photographs, illustrations, essays, and documents of Black life in the United States from the time of slavery to the 1920s. Random House had been uncertain about the project but its publication met with a good reception. Alvin Beam reviewed the anthology for the Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

'' Plain Dealer'', writing: "Editors, like novelists, have brain childrenbooks they think up and bring to life without putting their own names on the title page. Mrs. Morrison has one of these in the stores now, and magazines and newsletters in the publishing trade are ecstatic, saying it will go like hotcakes."

First writings and teaching, 1970–1986

Morrison had begun writing fiction as part of an informal group of poets and writers at Howard University who met to discuss their work. She attended one meeting with a short story about a Black girl who longed to have blue eyes. Morrison later developed the story as her first novel, '' The Bluest Eye'', getting up every morning at 4 am to write, while raising two children on her own. ''The Bluest Eye'' was published byHolt, Rinehart, and Winston

Holt McDougal is an American publishing company, a division of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, that specializes in textbooks for use in high schools.

The Holt name is derived from that of U.S. publisher Henry Holt (1840–1926), co-founder of the ...

in 1970, when Morrison was aged 39. It was favorably reviewed in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' by John Leonard, who praised Morrison's writing style as being "a prose so precise, so faithful to speech and so charged with pain and wonder that the novel becomes poetry ... But ''The Bluest Eye'' is also history, sociology, folklore, nightmare and music." The novel did not sell well at first, but the City University of New York

The City University of New York (CUNY, pronounced , ) is the Public university, public university system of Education in New York City, New York City. It is the largest urban university system in the United States, comprising 25 campuses: eleven ...

put ''The Bluest Eye'' on its reading list for its new Black studies

Black studies or Africana studies (with nationally specific terms, such as African American studies and Black Canadian studies), is an interdisciplinary academic field that primarily focuses on the study of the history, culture, and politics of ...

department, as did other colleges, which boosted sales. The book also brought Morrison to the attention of the acclaimed editor Robert Gottlieb

Robert Adams Gottlieb (April 29, 1931 – June 14, 2023) was an American writer and editor. He was the editor-in-chief of Simon & Schuster, Alfred A. Knopf, and ''The New Yorker''.

Gottlieb joined Simon & Schuster in 1955 as an editorial ass ...

at Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

, an imprint of the publisher Random House. Gottlieb later edited all but one of Morrison's novels.

In 1975, Morrison's second novel '' Sula'' (1973), about a friendship between two Black women, was nominated for the National Book Award

The National Book Awards (NBA) are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors. ...

. Her third novel, ''Song of Solomon

The Song of Songs (), also called the Canticle of Canticles or the Song of Solomon, is a biblical poem, one of the five ("scrolls") in the ('writings'), the last section of the Tanakh. Unlike other books in the Hebrew Bible, it is erotic poe ...

'' (1977), follows the life of Macon "Milkman" Dead III, from birth to adulthood, as he discovers his heritage. This novel brought her national acclaim, being a main selection of the Book of the Month Club

Book of the Month (founded 1926) is a United States subscription-based e-commerce service that offers a selection of five to seven new hardcover books each month to its members. Books are selected and endorsed by a panel of judges, and members ch ...

, the first novel by a Black writer to be so chosen since Richard Wright's '' Native Son'' in 1940. ''Song of Solomon'' also won the National Book Critics Circle Award

The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English".Barnard College

Barnard College is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college affiliated with Columbia University in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a grou ...

awarded Morrison its highest honor, the Barnard Medal of Distinction.

Morrison gave her next novel, '' Tar Baby'' (1981), a contemporary setting. In it, a looks-obsessed fashion model, Jadine, falls in love with Son, a penniless drifter who feels at ease with being Black.

Resigning from Random House in 1983, Morrison left publishing to devote more time to writing, while living in a converted boathouse on the Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

in Nyack, New York. She taught English at two branches of the State University of New York

The State University of New York (SUNY ) is a system of Public education, public colleges and universities in the New York (state), State of New York. It is one of the List of largest universities and university networks by enrollment, larges ...

(SUNY) and at Rutgers University's New Brunswick campus. In 1984, she was appointed to an Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (; 14 January 1875 – 4 September 1965) was a German and French polymath from Alsace. He was a theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician. As a Lutheran minister, ...

chair at the University at Albany, SUNY

The State University of New York at Albany (University at Albany, UAlbany, or SUNY Albany) is a Public university, public research university in Albany, New York, United States. Founded in 1844, it is one of four "university centers" of the St ...

.

Morrison's first play, '' Dreaming Emmett'', is about the 1955 murder by white men of Black teenager Emmett Till

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941 – August 28, 1955) was an African American youth, who was 14 years old when he was abducted and Lynching in the United States, lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of offending a white woman, ...

. The play was commissioned by the New York State Writers Institute at the State University of New York at Albany, where she was teaching at the time. It was produced in 1986 by Capital Repertory Theatre and directed by Gilbert Moses. Morrison was also a visiting professor at Bard College

Bard College is a private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. The campus overlooks the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains within the Hudson River Historic District ...

from 1986 to 1988.

''Beloved'' trilogy and the Nobel Prize: 1987–1998

In 1987, Morrison published her most celebrated novel, '' Beloved''. It was inspired by the true story of an enslaved African-American woman, Margaret Garner, whose story Morrison had discovered when compiling ''The Black Book''. Garner had escaped slavery but was pursued by slave hunters. Facing a return to slavery, Garner killed her two-year-old daughter but was captured before she could kill herself. Morrison's novel imagines the dead baby returning as a ghost, Beloved, to haunt her mother and family.

''Beloved'' was a critical success and a bestseller for 25 weeks. ''

In 1987, Morrison published her most celebrated novel, '' Beloved''. It was inspired by the true story of an enslaved African-American woman, Margaret Garner, whose story Morrison had discovered when compiling ''The Black Book''. Garner had escaped slavery but was pursued by slave hunters. Facing a return to slavery, Garner killed her two-year-old daughter but was captured before she could kill herself. Morrison's novel imagines the dead baby returning as a ghost, Beloved, to haunt her mother and family.

''Beloved'' was a critical success and a bestseller for 25 weeks. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' book reviewer Michiko Kakutani

is an American writer and retired literary critic, best known for reviewing books for ''The New York Times'' from 1983 to 2017. In that role, she won the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 1998.

Early life and family

Kakutani, a Japanese Americ ...

wrote that the scene of the mother killing her baby is "so brutal and disturbing that it appears to warp time before and after into a single unwavering line of fate". Canadian writer Margaret Atwood

Margaret Eleanor Atwood (born November 18, 1939) is a Canadian novelist, poet, literary critic, and an inventor. Since 1961, she has published 18 books of poetry, 18 novels, 11 books of nonfiction, nine collections of short fiction, eight chi ...

wrote in a review for ''The New York Times'', "Ms. Morrison's versatility and technical and emotional range appear to know no bounds. If there were any doubts about her stature as a pre-eminent American novelist, of her own or any other generation, ''Beloved'' will put them to rest."

Some critics panned ''Beloved''. African-American conservative social critic Stanley Crouch

Stanley Lawrence Crouch (December 14, 1945 – September 16, 2020) was an American cultural critic, poet, playwright, novelist, biographer, and syndicated columnist. He was known for his jazz criticism and his 2000 novel ''Don't the Moon Lo ...

, for instance, complained in his review in ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

'' that the novel "reads largely like a melodrama lashed to the structural conceits of the miniseries", and that Morrison "perpetually interrupts her narrative with maudlin ideological commercials".

Despite overall high acclaim, ''Beloved'' failed to win the prestigious National Book Award

The National Book Awards (NBA) are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors. ...

or the National Book Critics Circle Award

The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English".Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou ( ; born Marguerite Annie Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American memoirist, poet, and civil rights activist. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, several books of poetry, and is credi ...

, protested the omission in a statement that ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' published on January 24, 1988. "Despite the international stature of Toni Morrison, she has yet to receive the national recognition that her five major works of fiction entirely deserve", they wrote. Two months later, ''Beloved'' won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published during ...

. It also won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.

''Beloved'' is the first of three novels about love and African-American history, sometimes called the ''Beloved'' Trilogy. Morrison said they are intended to be read together, explaining: "The conceptual connection is the search for the beloved – the part of the self that is you, and loves you, and is always there for you." The second novel in the trilogy, ''Jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

'', came out in 1992. Told in language that imitates the rhythms of jazz music, the novel is about a love triangle during the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics, and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the ti ...

in New York City. According to Lyn Innes, "Morrison sought to change not just the content and audience for her fiction; her desire was to create stories which could be lingered over and relished, not 'consumed and gobbled as fast food', and at the same time to ensure that these stories and their characters had a strong historical and cultural base."

In 1992, Morrison also published her first book of literary criticism, '' Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination'' (1992), an examination of the African-American presence in White American literature. (In 2016, ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine noted that ''Playing in the Dark'' was among Morrison's most-assigned texts on U.S. college campuses, together with several of her novels and her 1993 Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

lecture.) Lyn Innes wrote in the ''Guardian

Guardian usually refers to:

* Legal guardian, a person with the authority and duty to care for the interests of another

* ''The Guardian'', a British daily newspaper

(The) Guardian(s) may also refer to:

Places

* Guardian, West Virginia, Unit ...

'' obituary of Morrison, "Her 1990 series of Massey lectures at Harvard were published as Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992), and explore the construction of a 'non-white Africanist presence and personae' in the works of Poe, Hawthorne, Melville, Cather and Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized f ...

, arguing that 'all of us are bereft when criticism remains too polite or too fearful to notice a disrupting darkness before its eyes'."

Before the third novel of the ''Beloved'' Trilogy was published, Morrison was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1993. The citation praised her as an author "who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality". She was the first Black woman of any nationality to win the prize. In her acceptance speech, Morrison said: "We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives."

In her Nobel lecture, Morrison talked about the power of storytelling. To make her point, she told a story. She spoke about a blind, old, Black woman who is approached by a group of young people. They demand of her, "Is there no context for our lives? No song, no literature, no poem full of vitamins, no history connected to experience that you can pass along to help us start strong? ... Think of our lives and tell us your particularized world. Make up a story."

In 1996, the National Endowment for the Humanities

The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) is an independent federal agency of the U.S. government, established by thNational Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965(), dedicated to supporting research, education, preserv ...

selected Morrison for the Jefferson Lecture

The Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities is an honorary lecture series established in 1972 by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). According to the NEH, the Lecture is "the highest honor the federal government confers for distinguished ...

, the U.S. federal government's highest honor for "distinguished intellectual achievement in the humanities".Jefferson Lecturersat NEH Website. Retrieved January 22, 2009. Morrison's lecture, entitled "The Future of Time: Literature and Diminished Expectations", began with the aphorism: "Time, it seems, has no future." She cautioned against the misuse of history to diminish expectations of the future. Morrison was also honored with the 1996 National Book Foundation's Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, which is awarded to a writer "who has enriched our literary heritage over a life of service, or a corpus of work". The third novel of her ''Beloved'' Trilogy, ''

Paradise

In religion and folklore, paradise is a place of everlasting happiness, delight, and bliss. Paradisiacal notions are often laden with pastoral imagery, and may be cosmogonical, eschatological, or both, often contrasted with the miseries of human ...

'', about citizens of an all-Black town, came out in 1997. The following year, Morrison was on the cover of ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine, making her only the second female writer of fiction and second Black writer of fiction to appear on what was perhaps the most significant U.S. magazine cover of the era.

''Beloved'' onscreen and "the Oprah effect"

Also in 1998, the movie adaptation of '' Beloved'' was released, directed byJonathan Demme

Robert Jonathan Demme ( ; February 22, 1944 – April 26, 2017) was an American filmmaker, whose career directing, producing, and screenwriting spanned more than 30 years and 70 feature films, documentaries, and television productions. He was an ...

and co-produced by Oprah Winfrey

Oprah Gail Winfrey (; born Orpah Gail Winfrey; January 29, 1954) is an American television presenter, talk show host, television producer, actress, author, and media proprietor. She is best known for her talk show, ''The Oprah Winfrey Show' ...

, who had spent ten years bringing it to the screen. Winfrey also stars as the main character, Sethe, alongside Danny Glover

Danny Glover ( ; born July 22, 1946) is an American actor, producer, and political activist. Over his career he has received List of awards and nominations received by Danny Glover, numerous accolades including the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian A ...

as Sethe's lover, Paul D, and Thandiwe Newton

Melanie Thandiwe Newton ( ; born 6 November 1972), formerly credited as Thandie Newton ( ), is a British actress. She has received various awards, including a Primetime Emmy Award, and a BAFTA Award, as well as nominations for two Golden Globe ...

as Beloved.

The movie flopped at the box office. A review in ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British newspaper published weekly in printed magazine format and daily on Electronic publishing, digital platforms. It publishes stories on topics that include economics, business, geopolitics, technology and culture. M ...

'' opined that "most audiences are not eager to endure nearly three hours of a cerebral film with an original storyline featuring supernatural themes, murder, rape, and slavery". Film critic Janet Maslin

Janet R. Maslin (born August 12, 1949) is an American journalist, who served as a film critic for ''The New York Times'' from 1977 to 1999, serving as chief critic for the last six years, and then a literary critic from 2000 to 2015. In 2000, M ...

, in her ''New York Times'' review "No Peace from a Brutal Legacy", called it a "transfixing, deeply felt adaptation of Toni Morrison's novel. ... Its linchpin is of course Oprah Winfrey, who had the clout and foresight to bring 'Beloved' to the screen and has the dramatic presence to hold it together." Film critic Roger Ebert

Roger Joseph Ebert ( ; June 18, 1942 – April 4, 2013) was an American Film criticism, film critic, film historian, journalist, essayist, screenwriter and author. He wrote for the ''Chicago Sun-Times'' from 1967 until his death in 2013. Eber ...

suggested that ''Beloved'' was not a genre ghost story but the supernatural was used to explore deeper issues and the non-linear structure of Morrison's story had a purpose.

In 1996, television talk-show host Oprah Winfrey selected ''Song of Solomon'' for her newly launched Book Club, which became a popular feature on her '' Oprah Winfrey Show''. An average of 13 million viewers watched the show's book club segments. As a result, when Winfrey selected Morrison's earliest novel ''The Bluest Eye'' in 2000, it sold another 800,000 paperback copies. John Young wrote in the ''African American Review

''African American Review'' is a scholarly aggregation of essays on African-American literature, theatre, film, the visual arts, and culture; interviews; poetry; fiction; and book reviews. It is the official publication of the Modern Language Ass ...

'' in 2001 that Morrison's career experienced the boost of " The Oprah Effect, ... enabling Morrison to reach a broad, popular audience."

Winfrey selected a total of four of Morrison's novels over six years, giving Morrison's works a bigger sales boost than they received from her Nobel Prize win in 1993. The novelist also appeared three times on Winfrey's show. Winfrey said, "For all those who asked the question 'Toni Morrison again?'... I say with certainty there would have been no Oprah's Book Club if this woman had not chosen to share her love of words with the world." Morrison called the book club a "reading revolution".

Early 21st century

Morrison continued to explore different art forms, such as providing texts for original scores of classical music. She collaborated withAndré Previn

André George Previn (; born Andreas Ludwig Priwin; April 6, 1929 – February 28, 2019) was a German-American pianist, composer, and conductor. His career had three major genres: Hollywood films, jazz, and classical music. In each he achieved ...

on the song cycle ''Honey and Rue'', which premiered with Kathleen Battle

Kathleen Deanna Battle (born August 13, 1948) is an American operatic soprano known for her distinctive vocal range and tone. Born in Portsmouth, Ohio, Battle initially became known for her work within the concert repertoire through performances ...

in January 1992, and on ''Four Songs'', premiered at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhattan), 57t ...

with Sylvia McNair

Sylvia McNair (born June 23, 1956) is an American opera singer and classical recitalist who has also achieved notable success in the Broadway and cabaret genres. McNair, a soprano, has made several critically acclaimed recordings and has won t ...

in November 1994. Both ''Sweet Talk: Four Songs on Text'' and ''Spirits In the Well'' (1997) were written for Jessye Norman

Jessye Mae Norman (September 15, 1945 – September 30, 2019) was an American opera singer and recitalist. She was able to perform dramatic soprano roles, but did not limit herself to that voice type. A commanding presence on operatic, concert ...

with music by Richard Danielpour, and, alongside Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou ( ; born Marguerite Annie Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American memoirist, poet, and civil rights activist. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, several books of poetry, and is credi ...

and Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Morrison provided the text for composer Judith Weir's ''woman.life.song'' commissioned by Carnegie Hall for Jessye Norman, which premiered in April 2000.

Morrison returned to Margaret Garner's life story, the basis of her novel ''Beloved'', to write the libretto

A libretto (From the Italian word , ) is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to th ...

for a new opera, '' Margaret Garner''. Completed in 2002, with music by Richard Danielpour, the opera was premièred on May 7, 2005, at the Detroit Opera House with Denyce Graves

Denyce Graves (born March 7, 1964) is an American mezzo-soprano opera singer.

Early life

Graves was born on March 7, 1964, in Washington, D.C., to Charles Graves and Dorothy (Middleton) Graves-Kenner. She is the middle of three children and w ...

in the title role."Rising Opera Star Angela M. Brown to replace Jessye Norman in World Premiere Production of Margaret Garner"Michigan Opera Theater, April 1, 2005. . ''

Love

Love is a feeling of strong attraction and emotional attachment (psychology), attachment to a person, animal, or thing. It is expressed in many forms, encompassing a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most su ...

'', Morrison's first novel since ''Paradise'', came out in 2003. In 2004, she put together a children's book called ''Remember'' to mark the 50th anniversary of the ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the ...

'' Supreme Court decision in 1954 that declared racially segregated public schools to be unconstitutional.

From 1997 to 2003, Morrison was an Andrew D. White Professor-at-Large at Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

.

In 2004, Morrison was invited by Wellesley College

Wellesley College is a Private university, private Women's colleges in the United States, historically women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Wellesley, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1870 by Henr ...

to deliver the commencement address

In the United States, a commencement speech or commencement address is a speech given to graduating students, generally at a university, although the term is also used for secondary education institutions and in similar institutions around the ...

, which has been described as "among the greatest commencement addresses of all time and a courageous counterpoint to the entire genre".

In June 2005, the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

awarded Morrison an honorary Doctor of Letters

Doctor of Letters (D.Litt., Litt.D., Latin: ' or '), also termed Doctor of Literature in some countries, is a terminal degree in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. In the United States, at universities such as Drew University, the degree ...

degree.

In the spring 2006, ''The New York Times Book Review

''The New York Times Book Review'' (''NYTBR'') is a weekly paper-magazine supplement to the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times'' in which current non-fiction and fiction books are reviewed. It is one of the most influential and widely rea ...

'' named ''Beloved'' the best work of American fiction published in the previous 25 years, as chosen by a selection of prominent writers, literary critics, and editors. In his essay about the choice, "In Search of the Best", critic A. O. Scott

Anthony Oliver Scott (born July 10, 1966) is an American journalist and cultural critic, known for his film and literary criticism. After starting his career at ''The New York Review of Books'', '' Variety'', and ''Slate'', he began writing film ...

said: "Any other outcome would have been startling since Morrison's novel has inserted itself into the American canon more completely than any of its potential rivals. With remarkable speed, 'Beloved' has, less than 20 years after its publication, become a staple of the college literary curriculum, which is to say a classic. This triumph is commensurate with its ambition since it was Morrison's intention in writing it precisely to expand the range of classic American literature, to enter, as a living Black woman, the company of dead White males like Faulkner, Melville, Hawthorne and Twain."

In November 2006, Morrison visited the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

museum in Paris as the second in its "Grand Invité" program to guest-curate a month-long series of events across the arts on the theme of "The Foreigner's Home", about which ''The New York Times'' said: "In tapping her own African-American culture, Ms. Morrison is eager to credit 'foreigners' with enriching the countries where they settle."

Morrison's novel ''A Mercy

''A Mercy'' is Toni Morrison's ninth novel. It was published in 2008 in literature, 2008. Set in colonial America in the late 17th century, it is the story of a European farmer, his purchased wife, and his growing household of indentured or ensl ...

'', released in 2008, is set in the Virginia colonies of 1682. Diane Johnson, in her review in '' Vanity Fair'', called ''A Mercy'' "a poetic, visionary, mesmerizing tale that captures, in the cradle of our present problems and strains, the natal curse put on us back then by the Indian tribes, Africans, Dutch, Portuguese, and English competing to get their footing in the New World against a hostile landscape and the essentially tragic nature of human experience."

Princeton years

From 1989 until her retirement in 2006, Morrison held the Robert F. Goheen Chair in the Humanities atPrinceton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

. She said she did not think much of modern fiction writers who reference their own lives instead of inventing new material, and she used to tell her creative writing students, "I don't want to hear about your little life, OK?" Similarly, she chose not to write about her own life in a memoir or autobiography.

Though based in the Creative Writing Program at Princeton, Morrison did not regularly offer writing workshops to students after the late 1990s, a fact that earned her some criticism. Rather, she conceived and developed the Princeton Atelier, a program that brings together students with writers and performing artists. Together the students and the artists produce works of art that are presented to the public after a semester of collaboration.

Inspired by her curatorship at the Louvre Museum, Morrison returned to Princeton in the fall 2008 to lead a small seminar, also entitled "The Foreigner's Home".

On November 17, 2017, Princeton University dedicated Morrison Hall (a building previously called West College) in her honor.

Inspired by her curatorship at the Louvre Museum, Morrison returned to Princeton in the fall 2008 to lead a small seminar, also entitled "The Foreigner's Home".

On November 17, 2017, Princeton University dedicated Morrison Hall (a building previously called West College) in her honor.

Final years: 2010–2019

In May 2010, Morrison appeared at PEN World Voices for a conversation with Marlene van Niekerk andKwame Anthony Appiah

Kwame Akroma-Ampim Kusi Anthony Appiah ( ; born 8 May 1954) is an English-American philosopher and writer who has written about political philosophy, ethics, the philosophy of language and mind, and African intellectual history. Appiah is Prof ...

about South African literature and specifically van Niekerk's 2004 novel ''Agaat''.

Morrison wrote books for children with her younger son, Slade Morrison, who was a painter and a musician. Slade died of pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer arises when cell (biology), cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control and form a Neoplasm, mass. These cancerous cells have the malignant, ability to invade other parts of ...

on December 22, 2010, aged 45, when Morrison's novel ''Home

A home, or domicile, is a space used as a permanent or semi-permanent residence for one or more human occupants, and sometimes various companion animals. Homes provide sheltered spaces, for instance rooms, where domestic activity can be p ...

'' (2012) was half-completed.

In May 2011, Morrison received an Honorary Doctor of Letters

Doctor of Letters (D.Litt., Litt.D., Latin: ' or '), also termed Doctor of Literature in some countries, is a terminal degree in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. In the United States, at universities such as Drew University, the degree ...

degree from Rutgers University–New Brunswick. During the commencement ceremony, she delivered a speech on the "pursuit of life, liberty, meaningfulness, integrity, and truth".

In 2011, Morrison worked with opera director

In 2011, Morrison worked with opera director Peter Sellars

Peter Sellars (born September 27, 1957) is an American theatre director, noted for his unique stagings of classical and contemporary operas and plays. Sellars is a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where he teaches ...

and Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

an singer-songwriter Rokia Traoré on ''Desdemona

Desdemona () is a character in William Shakespeare's play ''Othello'' (c. 1601–1604). Shakespeare's Desdemona is a Venice, Italy, Venetian beauty who enrages and disappoints her father, a Venetian senator, when she elopes with Othello (char ...

'', taking a fresh look at William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's tragedy ''Othello

''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'', often shortened to ''Othello'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare around 1603. Set in Venice and Cyprus, the play depicts the Moorish military commander Othello as he is manipulat ...

''. The trio focused on the relationship between Othello

''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'', often shortened to ''Othello'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare around 1603. Set in Venice and Cyprus, the play depicts the Moorish military commander Othello as he is manipulat ...

's wife Desdemona

Desdemona () is a character in William Shakespeare's play ''Othello'' (c. 1601–1604). Shakespeare's Desdemona is a Venice, Italy, Venetian beauty who enrages and disappoints her father, a Venetian senator, when she elopes with Othello (char ...

and her African nursemaid, Barbary, who is only briefly referenced in Shakespeare. The play, a mix of words, music and song, premiered in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

in 2011.

Morrison had stopped working on her latest novel when her son died in 2010, later explaining, "I stopped writing until I began to think, He would be really put out if he thought that he had caused me to stop. 'Please, Mom, I'm dead, could you keep going ...?

She completed ''Home

A home, or domicile, is a space used as a permanent or semi-permanent residence for one or more human occupants, and sometimes various companion animals. Homes provide sheltered spaces, for instance rooms, where domestic activity can be p ...

'' and dedicated it to her son Slade. Published in 2012, it is the story of a Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

veteran in the segregated United States of the 1950s who tries to save his sister from brutal medical experiments at the hands of a white doctor.

In August 2012, Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college and conservatory of music in Oberlin, Ohio, United States. Founded in 1833, it is the oldest Mixed-sex education, coeducational lib ...

became the home base of the Toni Morrison Society, an international literary society founded in 1993, dedicated to scholarly research of Morrison's work.

Morrison's eleventh novel, '' God Help the Child'', was published in 2015. It follows Bride, an executive in the fashion and beauty industry whose mother tormented her as a child for being dark-skinned, a trauma that has continued to dog Bride.

Morrison was a member of the editorial advisory board of ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

'', a magazine started in 1865 by Northern abolitionists.

Personal life

While teaching at Howard University from 1957 to 1964, she met Harold Morrison, a Jamaican architect, whom she married in 1958. She took his last name, and became known as Toni Morrison. Their first son, Harold Ford, was born in 1961. She was pregnant when she and Harold divorced in 1964. Her second son, Slade Kevin Morrison, was born in 1965; he died ofpancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer arises when cell (biology), cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control and form a Neoplasm, mass. These cancerous cells have the malignant, ability to invade other parts of ...

on December 22, 2010, when Morrison was halfway through writing her novel ''Home

A home, or domicile, is a space used as a permanent or semi-permanent residence for one or more human occupants, and sometimes various companion animals. Homes provide sheltered spaces, for instance rooms, where domestic activity can be p ...

.'' She stopped work on the novel for a year or two before completing it; it was published in 2012.

Death

Morrison died at Montefiore Medical Center inThe Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, New York City, on August 5, 2019, from complications of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

. She was 88 years old.

A memorial tribute was held on November 21, 2019, at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (sometimes referred to as St. John's and also nicknamed St. John the Unfinished) is the cathedral of the Episcopal Diocese of New York. It is at 1047 Amsterdam Avenue in the Morningside Heights neighborhoo ...

in the Morningside Heights

Morningside Heights is a neighborhood on the West Side of Upper Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Morningside Drive to the east, 125th Street to the north, 110th Street to the south, and Riverside Drive to the west. Morningsi ...

neighborhood of Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

in New York City. Morrison was eulogized by, among others, Oprah Winfrey

Oprah Gail Winfrey (; born Orpah Gail Winfrey; January 29, 1954) is an American television presenter, talk show host, television producer, actress, author, and media proprietor. She is best known for her talk show, ''The Oprah Winfrey Show' ...

, Angela Davis

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American Marxist and feminist political activist, philosopher, academic, and author. She is Distinguished Professor Emerita of Feminist Studies and History of Consciousness at the University of ...

, Michael Ondaatje

Philip Michael Ondaatje (; born 12 September 1943) is a Sri Lankan-born Canadian poet, fiction writer and essayist.

Ondaatje's literary career began with his poetry in 1967, publishing ''The Dainty Monsters'', and then in 1970 the critically a ...

, David Remnick, Fran Lebowitz

Frances Ann Lebowitz (; born October 27, 1950) is an American author, public speaker, and actor. She is known for her sardonic social commentary on American life as filtered through her New York City sensibilities and her association with many p ...

, Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Paul Coates ( ; born September 30, 1975) is an American author, journalist, and activist. He gained a wide readership during his time as national correspondent at ''The Atlantic'', where he wrote about cultural, social, and political is ...

, and Edwidge Danticat

Edwidge Danticat (; born January 19, 1969) is a Haitian American novelist and short story writer. Her first novel, '' Breath, Eyes, Memory'', was published in 1994 and went on to become an Oprah's Book Club selection. Danticat has since written ...

. The jazz saxophonist David Murray performed a musical tribute.

Politics, literary reception, and legacy

Politics

Morrison spoke openly about American politics and race relations. In writing about the 1998impeachment of Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton, the List of presidents of the United States, 42nd president of the United States, was Federal impeachment in the United States, impeached by the United States House of Representatives of the 105th United States Congress on Decem ...

, she claimed that since Whitewater

Whitewater forms in the context of rapids, in particular, when a river's Stream gradient, gradient changes enough to generate so much turbulence that air is trapped within the water. This forms an unstable current that foam, froths, making t ...

, Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

was being mistreated in the same way Black people often are:

The phrase "our first Black president" was adopted as a positive by Bill Clinton supporters. When the Congressional Black Caucus

The Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) is made up of Black members of the United States Congress. Representative Yvette Clarke from New York, the current chairperson, succeeded Steven Horsford from Nevada in 2025. Although most members belong ...

honored the former president at its dinner in Washington, D.C., on September 29, 2001, for instance, Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX), the chair, told the audience that Clinton "took so many initiatives he made us think for a while we had elected the first black president".

In the context of the 2008 Democratic Primary campaign, Morrison stated to ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine: "People misunderstood that phrase. I was deploring the way in which President Clinton was being treated, vis-à-vis the sex scandal that was surrounding him. I said he was being treated like a black on the street, already guilty, already a perp. I have no idea what his real instincts are, in terms of race." In the Democratic primary contest for the 2008 presidential race, Morrison endorsed Senator Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

over Senator Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. She was the 67th United States secretary of state in the administration of Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, a U.S. senator represent ...

, though expressing admiration and respect for the latter. When he won, Morrison said she felt like an American for the first time. She said, "I felt very powerfully patriotic when I went to the inauguration of Barack Obama. I felt like a kid."

In April 2015, speaking of the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

– three unarmed Black men killed by white police officers – Morrison said: "People keep saying, 'We need to have a conversation about race.' This is the conversation. I want to see a cop shoot a white unarmed teenager in the back. And I want to see a white man convicted for raping a Black woman. Then when you ask me, 'Is it over?', I will say yes."

After the 2016 election of Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

as President of the United States, Morrison wrote an essay, "Mourning for Whiteness", published in the November 21, 2016 issue of ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

''. In it she argues that white Americans are so afraid of losing privileges afforded them by their race that white voters elected Trump, whom she described as being "endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

", in order to keep the idea of white supremacy

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

alive.

Relationship to feminism

Although her novels typically concentrate on black women, Morrison did not identify her works asfeminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

. When asked in a 1998 interview, "Why distance oneself from feminism?" she replied: "In order to be as free as I possibly can, in my own imagination, I can't take positions that are closed. Everything I've ever done, in the writing world, has been to expand articulation, rather than to close it, to open doors, sometimes, not even closing the book – leaving the endings open for reinterpretation, revisitation, a little ambiguity." She went on to state that she thought it "off-putting to some readers, who may feel that I'm involved in writing some kind of feminist tract. I don't subscribe to patriarchy, and I don't think it should be substituted with matriarchy. I think it's a question of equitable access, and opening doors to all sorts of things."

In 2012, she responded to a question about the difference between black and white feminists in the 1970s. " Womanists is what black feminists used to call themselves", she explained. "They were not the same thing. And also the relationship with men. Historically, black women have always sheltered their men because they were out there, and they were the ones that were most likely to be killed."

W. S. Kottiswari writes in ''Postmodern Feminist Writers'' (2008) that Morrison exemplifies characteristics of " postmodern feminism" by "altering Euro-American dichotomies by rewriting a history written by mainstream historians" and by her usage of shifting narration in ''Beloved'' and ''Paradise''. Kottiswari states: "Instead of western logocentric abstractions, Morrison prefers the powerful vivid language of women of color ... She is essentially postmodern since her approach to myth and folklore is re-visionist."

Contributions to Black feminism

Many of Morrison's works have been cited by scholars as significant contributions to Black feminism, reflecting themes of race, gender, and sexual identity within her narratives. Barbara Smith's 1977 essay "Toward a Black Feminist Criticism" argues that Morrison's ''Sula'' is a work of Black feminism, as it presents a lesbian perspective that challenges heterosexual relationships and the conventional family unit. Smith states, "Consciously or not, Morrison's work poses both lesbian and feminist questions about Black women's autonomy and their impact upon each other's lives."Hilton Als

Hilton Als (born 1960) is an American writer and theater critic. He is a teaching professor at the University of California, Berkeley, an associate professor of writing at Columbia University and a staff writer and theater critic for ''The New Yo ...

's 2003 profile in ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

'' notes that "Before the late sixties, there was no real Black Studies curriculum in the academy—let alone a post-colonial-studies program or a feminist one. As an editor and author, Morrison, backed by the institutional power of Random House, provided the material for those discussions to begin."

Morrison consistently advocated for feminist ideas that challenge the dominance of the white patriarchal system, frequently rejecting the notion of writing from the perspective of the "white male gaze". Feminist political activist Angela Davis

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American Marxist and feminist political activist, philosopher, academic, and author. She is Distinguished Professor Emerita of Feminist Studies and History of Consciousness at the University of ...

notes that "Toni Morrison's project resides precisely in the effort to discredit the notion that this white male gaze must be omnipresent."

In a 1998 episode of ''Charlie Rose'', Morrison responded to a review of ''Sula'', stating, "I remember a review of ''Sula'' in which the reviewer said, 'One day, she', meaning me, 'will have to face up 'to the real responsibilities, and get mature, 'and write about the real confrontation 'for black people, which is white people.' As though our lives have no meaning and no depth without the white gaze, and I have spent my entire writing life trying to make sure that the white gaze was not the dominant one in any of my books."

In a 2015 interview with ''The New York Times Magazine

''The New York Times Magazine'' is an American Sunday magazine included with the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times''. It features articles longer than those typically in the newspaper and has attracted many notable contributors. The magazi ...

'', Morrison reiterated her intention to write without the white gaze, stating, "What I'm interested in is writing without the gaze, without the white gaze. In so many earlier books by African-American writers, particularly the men, I felt that they were not writing to me. But what interested me was the African-American experience throughout whichever time I spoke of. It was always about African-American culture and people – good, bad, indifferent, whatever – but that was, for me, the universe."

Regarding the racial environment in which she wrote, Morrison stated, "Navigating a white male world was not threatening. It wasn't even interesting. I was more interesting than they were. I knew more than they did. And I wasn't afraid to show it."

In a 1986 interview with Sandi Russell, Morrison stated that she wrote primarily for Black women, explaining, "I write for black women. We are not addressing the men, as some white female writers do. We are not attacking each other, as both black and white men do. Black women writers look at things in an unforgiving/loving way. They are writing to repossess, re-name, re-own."

In a 2003 interview, when asked about the labels "black" and "female" being attached to her work, Morrison replied, "I can accept the labels because being a black woman writer is not a shallow place but a rich place to write from. It doesn't limit my imagination; it expands it. It's richer than being a white male writer because I know more and I've experienced more."

In a 1987 article in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...