Swedish Pomerania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

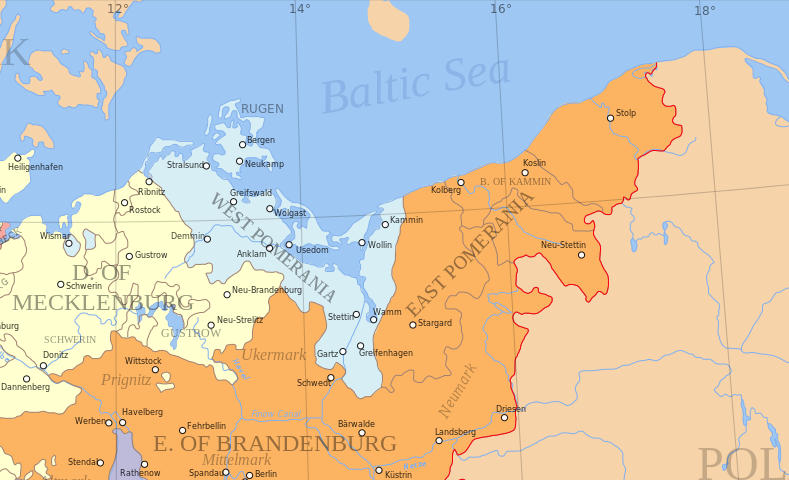

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a

Pomerania became involved in the

Pomerania became involved in the

The

The

By royal proclamation on 26 June 1806, the Constitution of Pomerania was declared to have been suspended and abolished. The Swedish Instruments of Government of 1772, the Act of Union and Security of 1789, and the Law of 1734 were declared to have taken precedence and were to be implemented following 1 September 1808. The reason for perpetrating this royally sanctioned

By royal proclamation on 26 June 1806, the Constitution of Pomerania was declared to have been suspended and abolished. The Swedish Instruments of Government of 1772, the Act of Union and Security of 1789, and the Law of 1734 were declared to have taken precedence and were to be implemented following 1 September 1808. The reason for perpetrating this royally sanctioned

*

*

* Count Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld (1651–1722) a Swedish Field Marshal; born in Stralsund

*

* Count Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld (1651–1722) a Swedish Field Marshal; born in Stralsund

*

Dissertation written in Swedish available as a PDF file

Foundation for the Swedish Cultural Heritage in PomeraniaDänholm Island, Swedish Pomerania August 1807

at NapoleonSeries.org

at NapoleonSeries.org

at library.ucla.edu {{coord, 54, 05, N, 13, 23, E, type:country_source:kolossus-cawiki, display=title 1630 establishments in Europe 1815 disestablishments in Europe States and territories established in 1630

dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

coast of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

, Sweden held extensive control over the lands on the southern Baltic coast, including Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and parts of Livonia

Livonia ( liv, Līvõmō, et, Liivimaa, fi, Liivinmaa, German and Scandinavian languages: ', archaic German: ''Liefland'', nl, Lijfland, Latvian and lt, Livonija, pl, Inflanty, archaic English: ''Livland'', ''Liwlandia''; russian: Ли ...

and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

(''dominium maris baltici

The establishment of a , . ("Baltic Sea dominion") was one of the primary political aims of the Danish and Swedish kingdoms in the late medieval and early modern eras. Throughout the Northern Wars the Danish and Swedish navies played a second ...

'').

Sweden, which had been present in Pomerania with a garrison at Stralsund since 1628, gained effective control of the Duchy of Pomerania with the Treaty of Stettin in 1630. At the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pe ...

in 1648 and the Treaty of Stettin in 1653, Sweden received Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

(German ''Vorpommern''), with the islands of Rügen

Rügen (; la, Rugia, ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic city of Stralsund, where ...

, Usedom

Usedom (german: Usedom , pl, Uznam ) is a Baltic Sea island in Pomerania, divided between Germany and Poland. It is the second largest Pomeranian island after Rügen, and the most populous island in the Baltic Sea.

It is north of the Szczeci ...

, and Wolin

Wolin (; formerly german: Wollin ) is the name both of a Polish island in the Baltic Sea, just off the Polish coast, and a town on that island. Administratively, the island belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship. Wolin is separated from th ...

, and a strip of Farther Pomerania (''Hinterpommern''). The peace treaties were negotiated while the Swedish queen Christina was a minor, and the Swedish Empire

The Swedish Empire was a European great power that exercised territorial control over much of the Baltic region during the 17th and early 18th centuries ( sv, Stormaktstiden, "the Era of Great Power"). The beginning of the empire is usually ta ...

was governed by members of the high aristocracy. As a consequence, Pomerania was not annexed to Sweden like the French war gains, which would have meant abolition of serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, since the Pomeranian peasant laws of 1616 was practised there in its most severe form. Instead, it remained part of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, making the Swedish rulers ''Reichsfürsten'' (imperial princes) and leaving the nobility in full charge of the rural areas and its inhabitants. While the Swedish Pomeranian nobles were subjected to reduction when the late 17th century kings regained political power, the provisions of the peace of Westphalia continued to prevent the pursuit of the uniformity policy in Pomerania until the Holy Roman empire was dissolved in 1806.

In 1679, Sweden lost most of its Pomeranian possessions east of the Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

river in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, and in 1720, Sweden lost its possessions south of the Peene and east of the Peenestrom rivers in the Treaty of Stockholm. These areas were ceded to Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohe ...

and were integrated into Brandenburgian Pomerania. Also in 1720, Sweden regained the remainder of its dominion in the Treaty of Frederiksborg

The Treaty of Frederiksborg ( da, Frederiksborgfreden) was a treaty signed at Frederiksborg Castle, Zealand, on 3 July 1720Heitz (1995), p.244 (14 July 1720 according to the Gregorian calendar), ending the Great Northern War between Denmark-No ...

, which had been lost to Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

in 1715. In 1814, as a result of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

, Swedish Pomerania was ceded to Denmark in exchange for Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

in the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel ( da, Kieltraktaten) or Peace of Kiel ( Swedish and no, Kielfreden or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on t ...

, and in 1815, as a result of the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon ...

, transferred to Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

.

Geography

The largest cities in Swedish Pomerania wereStralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

, Greifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (german: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald, Low German: ''Griepswoold'') is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rosto ...

and, until 1720, Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

(now Szczecin). Rügen

Rügen (; la, Rugia, ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic city of Stralsund, where ...

is today Germany's largest island.

Acquisition during the Thirty Years' War

Pomerania became involved in the

Pomerania became involved in the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

during the 1620s, and with the town of Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

under siege by imperial troops, its ruler Bogislaw XIV, Duke of Stettin, concluded a treaty with King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S_19_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/now ...

in June 1628. On 10 July 1630, the treaty was extended into an 'eternal' pact in the Treaty of Stettin (1630). By the end of that year, the Swedes had completed the military occupation of Pomerania. After this point, Gustavus Adolphus was the effective ruler of the country, and even though the rights of succession to Pomerania, held by George William, Elector of Brandenburg due to the Treaty of Grimnitz, were recognised, the Swedish king still demanded that the Margraviate of Brandenburg

The Margraviate of Brandenburg (german: link=no, Markgrafschaft Brandenburg) was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806 that played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

Brandenburg developed out ...

break with Emperor Ferdinand II. In 1634, the Estates of Pomerania assigned the interim government to an eight-member directorate, which lasted until Brandenburg ordered the directorate disbanded in 1638 by right of Imperial investiture.

As a consequence, Pomerania lapsed into a state of anarchy, thereby forcing the Swedes to act. From 1641, the administration was led by a council ("Concilium status") from Stettin (Szczecin), until the peace treaty in 1648 settled rights to the province in Swedish favour. At the peace negotiations in Osnabrück, Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohe ...

received Farther Pomerania (''Hinterpommern''), the part of the former Duchy of Pomerania east of the Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

River except Stettin. A strip of land east of the Oder River

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows t ...

containing the districts of Damm and Gollnow and the island of Wolin

Wolin (; formerly german: Wollin ) is the name both of a Polish island in the Baltic Sea, just off the Polish coast, and a town on that island. Administratively, the island belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship. Wolin is separated from th ...

and Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

(''Vorpommern'') with the islands of Rügen

Rügen (; la, Rugia, ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic city of Stralsund, where ...

and Usedom

Usedom (german: Usedom , pl, Uznam ) is a Baltic Sea island in Pomerania, divided between Germany and Poland. It is the second largest Pomeranian island after Rügen, and the most populous island in the Baltic Sea.

It is north of the Szczeci ...

, was ceded to the Swedes as a fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

from Emperor Ferdinand III. The recess of Stettin in 1653 settled the border with Brandenburg in a manner favourable to Sweden. The border against Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label= Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schweri ...

, along the Trebel and the Recknitz, followed a settlement of 1591.

Constitution and administration

nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

of Pomerania was firmly established and held extensive privileges, as opposed to the other end of the spectrum which was populated by a class of numerous serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

. Even by the end of the 18th century, the serfs made up two-thirds of the population of the countryside. The estates owned by the nobility were divided into districts and the royal domains, which covered about a quarter of the country, were divided into ''amts''.

One fourth of the "knightly" estates (''Rittergut'') in Swedish Pomerania were held by Swedish nobles. The ducal estates (''Domäne''), initially distributed among Swedish nobles (two thirds) and officials, became in 1654 administered by the former Swedish queen Christina. Swedish and Pomeranian nobility intermarried and became ethnically indistinguishable in the course of the 18th century.

The position of Pomerania in the Swedish Realm came to depend on the talks that were opened between the Estates of Pomerania

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed and ...

and the Government of Sweden

The Government of the Kingdom of Sweden ( sv, Konungariket Sveriges regering) is the national cabinet of Sweden, and the country's executive authority.

The Government consists of the Prime Ministerappointed and dismissed by the Speaker of the ...

. The talks showed few results until the Instrument of Government of 17 July 1663 (promulgated by the recess of 10 April 1669) could be presented, and only in 1664 did the Pomeranian Estates salute the Swedish Monarch as their new ruler.

The Royal Government of Pomerania (''die königliche Landesregierung'') was composed of the Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

, who always was a Swedish Privy Councillor, as chairman and five Councillors of the Royal Government, among them the President of the Appellate Court, the Chancellor and the Castle Captain of Stettin, over inspector of the Royal Amts. When circumstances demanded, the estates, nobility, burgesses, and — until the 1690s — the clergy could be summoned for meetings of a local parliament called the ''Landtag

A Landtag (State Diet) is generally the legislative assembly or parliament of a federated state or other subnational self-governing entity in German-speaking nations. It is usually a unicameral assembly exercising legislative competence in non ...

''. The nobility was represented by one deputy per district, and these deputies were in turn mandated by their respective district convents of nobles. The estate of the burgesses consisted of one deputy per politically franchised city, particularly Stralsund. The ''Landtag'' were presided over by a marshal (''Erb-landmarschall''). A third element of the meeting of the Estates were the five, initially ten, ''Landtag'' councillors who were appointed by the Royal Government of Pomerania following their nomination by the Estates. The Landtag councillors formed the ''Land Council'', which mediated with the Swedish Government and oversaw the constitution.

The Estates, which had exercised great authority under the Pomeranian dukes, were unable to exert any significant influence on Sweden, even though the Constitution of 1663 had provided them with a veto in as far as Pomerania was affected. Their rights of petition were however not limited, and by the privileges of King Frederick I of Sweden

Frederick I ( sv, Fredrik I; 28 April 1676 – 5 April 1751) was prince consort of Sweden from 1718 to 1720, and List of Swedish monarchs, King of Sweden from 1720 until his death and (as ''Frederick I'') also Landgrave of Landgraviate of Hesse-K ...

in 1720 they also had an explicit right to participate in legislation and taxation.

The towns of Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

, Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

, Greifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (german: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald, Low German: ''Griepswoold'') is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rosto ...

and Anklam

Anklam [], formerly known as Tanglim and Wendenburg, is a town in the Western Pomerania region of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is situated on the banks of the Peene river, just 8 km from its mouth in the ''Kleines Haff'', the western ...

were granted autonomous jurisdiction.Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.253,

Legal system

The legal system in Pomerania was in a state of great confusion, due to the lack of a consistent legislation or even the most basic collection of laws and instead consisting of a disparate collection of legal principles. The Swedish rule brought, if nothing else, at least the rule of law into the court system. Starting in 1655, cases could be appealed from the first instance courts to the appellate court inGreifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (german: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald, Low German: ''Griepswoold'') is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rosto ...

(located in Wolgast

Wolgast (; csb, Wòłogòszcz) is a town in the district of Vorpommern-Greifswald, in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is situated on the bank of the river (or strait) Peenestrom, vis-a-vis the island of Usedom on the Baltic coast that can b ...

from 1665 to 1680), where sentences were issued under the appellate law of 1672, a work conducted by David Mevius. Cases under canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is t ...

were directed to a consistorium in Greifswald. From the appellate court cases could be appealed to the supreme court for the Swedish dominions in Germany, the High Tribunal in Wismar, which had opened in 1653.

Second Northern and Scanian Wars

From 1657 to 1659 during theSecond Northern War

The Second Northern War (1655–60), (also First or Little Northern War) was fought between Sweden and its adversaries the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1655–60), the Tsardom of Russia ( 1656–58), Brandenburg-Prussia (1657–60), the ...

, Polish, Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

, and Brandenburger troops ravaged the country. The territory was occupied by Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

and Brandenburg from 1675 to 1679 during the Scanian War

The Scanian War ( da, Skånske Krig, , sv, Skånska kriget, german: Schonischer Krieg) was a part of the Northern Wars involving the union of Denmark–Norway, Brandenburg and Sweden. It was fought from 1675 to 1679 mainly on Scanian soil, ...

, whereby Denmark claimed Rügen and Brandenburg the rest of Pomerania. Both campaigns were in vain for the winners when Swedish Pomerania was restored to Sweden in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1679, except for Gollnow and the strip of land on the east side of the Oder, which were held by Brandenburg as a pawn in exchange for reparations, until these were paid in 1693.

Because Pomerania had been hit hard by the Thirty Years' War already and found it hard to recover during the following years, the Swedish government in 1669 and 1689 issued decrees (''Freiheitspatente'') freeing anyone of taxes who built or rebuilt a house. These decrees were in force, though frequently modified, until 1824.

Territorial changes during the Great Northern War

The first years of theGreat Northern War

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swe ...

did not affect Pomerania. Even when Danish, Russian, and Polish forces had crossed the borders in 1714, the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

first appeared as a hesitant mediator before turning into an aggressor. King Charles XII of Sweden

Charles XII, sometimes Carl XII ( sv, Karl XII) or Carolus Rex (17 June 1682 – 30 November 1718 O.S.), was King of Sweden (including current Finland) from 1697 to 1718. He belonged to the House of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, a branch line of ...

in the Battle of Stralsund led the defence of Pomerania for an entire year, November 1714 to December 1715, before fleeing to Lund

Lund (, , ) is a city in the southern Swedish province of Scania, across the Öresund strait from Copenhagen. The town had 91,940 inhabitants out of a municipal total of 121,510 . It is the seat of Lund Municipality, Scania County. The Öre ...

. The Danes seized Rügen and Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

north of the Peene River (the former Danish Principality of Rugia

A principality (or sometimes princedom) can either be a monarchical feudatory or a sovereign state, ruled or reigned over by a regnant-monarch with the title of prince and/or princess, or by a monarch with another title considered to fall under ...

that later would become known as New Western Pomerania or ''Neuvorpommern''), while the Western Pomeranian areas south of the river (later termed Old Western Pomerania or ''Altvorpommern'') were taken by Prussia.

Danish Pomerania was since April 1716 governed by a governmental commission seated in Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

, consisting of five members. In contrast to the Swedish administration, the commission exerted both judiciary and executive power. Denmark thereby drew from the experiences in Danish-occupied Bremen-Verden

), which is a public-law corporation established in 1865 succeeding the estates of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen (established in 1397), now providing the local fire insurance in the shown area and supporting with its surplusses cultural effor ...

(1712–1715), the setting of the Danish chancellery, and the contemporary Danish absolutism under king Frederik IV of Denmark-Norway

Frederick IV (Danish: ''Frederik''; 11 October 1671 – 12 October 1730) was King of Denmark and Norway from 1699 until his death. Frederick was the son of Christian V of Denmark-Norway and his wife Charlotte Amalie of Hesse-Kassel.

Early life

...

. The commission consisted of landdrost {{Use dmy dates, date=December 2020

''Landdrost'' was the title of various officials with local jurisdiction in the Netherlands and a number of former territories in the Dutch Empire. The term is a Dutch compound, with ''land'' meaning "region" an ...

von Platen, later von Kötzschau, counsellors Heinrich Bernhard von Kämpferbeck, J. B. Hohenmühle and Peter von Thienen, and chancellor secretary August J. von John

August is the eighth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars, and the fifth of seven months to have a length of 31 days. Its zodiac sign is Leo and was originally named ''Sextilis'' in Latin because it was the 6th month in ...

. In 1720, von Kämpferbeck died and was replaced by Andreas Boye.

By the Treaty of Frederiksborg

The Treaty of Frederiksborg ( da, Frederiksborgfreden) was a treaty signed at Frederiksborg Castle, Zealand, on 3 July 1720Heitz (1995), p.244 (14 July 1720 according to the Gregorian calendar), ending the Great Northern War between Denmark-No ...

, 3 June 1720, Denmark was obliged to hand back control over the occupied territory to Sweden, but in the Treaty of Stockholm, on 21 January the same year, Prussia had been allowed to retain its conquest, including Stettin. By this, Sweden ceded the parts east of the Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

River that had been won in 1648 as well as Western Pomerania south of the Peene and the islands of Wolin and Usedom to Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohe ...

.

Denmark returned its Pomeranian territories to Swedish administration on 17 January 1721. The administrative records from the Danish period were transferred to Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan a ...

and are available at the Danish National Archives

, nativename_a =

, nativename_r =

, logo =

, logo_width = 300px

, logo_caption =

, seal =

, seal_width =

, seal_caption =

, picture = File:Rigsarkivet.jpg

, picture_width =

, picture_cap ...

(rigsarkivet).

Seven Years' War

A feeble Swedish attempt to regain the lost territories in the Pomeranian campaigns of theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

(1757–1762, "Pomeranian War

The Pomeranian War was a theatre of the Seven Years' War. The term is used to describe the fighting between Sweden and Prussia between 1757 and 1762 in Swedish Pomerania, Prussian Pomerania, northern Brandenburg and eastern Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

...

") failed. Swedish troops struggled to co-ordinate with their French and Russian allies, and what had begun as a Swedish invasion of Prussian Pomerania soon led to the Prussians occupying much of Swedish Pomerania and threatening Stralsund. When Russia made peace with Prussia in 1762, Sweden also dropped out of the war with a return to the status quo ante bellum

The term ''status quo ante bellum'' is a Latin phrase meaning "the situation as it existed before the war".

The term was originally used in treaties to refer to the withdrawal of enemy troops and the restoration of prewar leadership. When use ...

. Sweden's disappointing performance in the war further hurt its international prestige.

Integration in the eleventh hour

By royal proclamation on 26 June 1806, the Constitution of Pomerania was declared to have been suspended and abolished. The Swedish Instruments of Government of 1772, the Act of Union and Security of 1789, and the Law of 1734 were declared to have taken precedence and were to be implemented following 1 September 1808. The reason for perpetrating this royally sanctioned

By royal proclamation on 26 June 1806, the Constitution of Pomerania was declared to have been suspended and abolished. The Swedish Instruments of Government of 1772, the Act of Union and Security of 1789, and the Law of 1734 were declared to have taken precedence and were to be implemented following 1 September 1808. The reason for perpetrating this royally sanctioned coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

was that the estates, despite a royal prohibition, had taken to the courts to appeal against royal statutes, specifically the statute of 30 April 1806 regarding the raising of a Pomeranian army. In the new order, King Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden

Gustav IV Adolf or Gustav IV Adolph (1 November 1778 – 7 February 1837) was King of Sweden from 1792 until he was deposed in a coup in 1809. He was also the last Swedish monarch to be the ruler of Finland.

The occupation of Finland in 1808–09 ...

attempted to introduce a government divided into departments. Swedish church law was introduced. The country was divided into four hundreds ('' Härad'') containing parishes

(''Socken

Socken is the name used for a part of a county in Sweden. In Denmark similar areas are known as ''sogn'', in Norway ''sokn'' or ''sogn'' and in Finland ''pitäjä'' ''(socken)''. A socken is a country-side area that was formed around a church, ...

'') complying with the Swedish model of administration. The Estates of Pomerania could only be called regarding questions that specifically concerned Pomerania and Rügen. The new order of the Landtag was modelled on the Swedish Riksdag of the Estates

Riksdag of the Estates ( sv, Riksens ständer; informally sv, Ståndsriksdagen) was the name used for the Estates of Sweden when they were assembled. Until its dissolution in 1866, the institution was the highest authority in Sweden next to t ...

and a meeting according to the new order also took place in August 1806, which declared its loyalty to the king and hailed him as their ruler. In the wake of this revolution, a number of social reforms were implemented and planned; the most important was the abolishment of serfdom by a royal statute on 4 July 1806.

Also in 1806, Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden

Gustav IV Adolf or Gustav IV Adolph (1 November 1778 – 7 February 1837) was King of Sweden from 1792 until he was deposed in a coup in 1809. He was also the last Swedish monarch to be the ruler of Finland.

The occupation of Finland in 1808–09 ...

started constructing another major port city in Pomerania, Gustavia. Yet already in 1807, French forces occupied the site.

Loss during the Napoleonic Wars

The entry into theThird Coalition

The War of the Third Coalition)

* In French historiography, it is known as the Austrian campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Autriche de 1805) or the German campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Allemagne de 1805) was a European conflict spanni ...

in 1805, in which Sweden unsuccessfully fought its first war against Napoleon, subsequently led to the occupation of Swedish Pomerania by French troops from 1807 to 1810. After the Treaty of Paris signed in 1810, the territory was returned to Sweden. In 1812, when French troops yet again marched into Pomerania, the Swedish Army

The Swedish Army ( sv, svenska armén) is the land force of the Swedish Armed Forces.

History

Svea Life Guards dates back to the year 1521, when the men of Dalarna chose 16 young able men as body guards for the insurgent nobleman Gustav ...

mobilized

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and t ...

and assisted against Napoleon in the Battle of Leipzig

The Battle of Leipzig (french: Bataille de Leipsick; german: Völkerschlacht bei Leipzig, ); sv, Slaget vid Leipzig), also known as the Battle of the Nations (french: Bataille des Nations; russian: Битва народов, translit=Bitva ...

in 1813, together with troops from Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Sweden also attacked Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

and, by the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel ( da, Kieltraktaten) or Peace of Kiel ( Swedish and no, Kielfreden or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on t ...

on 14 January 1814, Sweden ceded Pomerania to Denmark in exchange for Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

.

The fate of Swedish Pomerania was settled during the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon ...

through the treaties between Prussia and Denmark on 4 June and with Sweden on 7 June 1815. In this manoeuvre Prussia gained Swedish Pomerania in exchange for Saxe-Lauenburg

The Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg (german: Herzogtum Sachsen-Lauenburg, called ''Niedersachsen'' (Lower Saxony) between the 14th and 17th centuries), was a ''reichsfrei'' duchy that existed from 1296–1803 and again from 1814–1876 in the extreme sou ...

, becoming Danish, with Prussia having bartered previously Hanoverian Saxe-Lauenburg only 14 years earlier in exchange for East Frisia

East Frisia or East Friesland (german: Ostfriesland; ; stq, Aastfräislound) is a historic region in the northwest of Lower Saxony, Germany. It is primarily located on the western half of the East Frisian peninsula, to the east of West Frisia ...

ceded to Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

again. Denmark also received 2.6 million Thaler

A thaler (; also taler, from german: Taler) is one of the large silver coins minted in the states and territories of the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy during the Early Modern period. A ''thaler'' size silver coin has a diameter o ...

s from Prussia. 3.5 million Thalers were awarded to Sweden in war damages. "Swedish Pomerania" was incorporated into Prussia as New Western Pomerania (''Neuvorpommern'') within the Prussian Province of Pomerania.

Population

The population of Swedish Pomerania was 82,827 subjects in 1764, (58,682 rural, 24,145 urban population, 40% of the rural population were ''leibeigen''serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

s);Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, p.191, 89,000 in 1766, 113,000 in 1802, with about a quarter living on the island of Rügen, and had reached 118,112 in 1805 (79,087 rural, 39,025 urban population, 46,190 of the rural population were ''leibeigen'' serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

s).

List of governors-general

Source:Notable people

*

* Johann Franz Buddeus

Johann Franz Buddeus or Budde (sometimes Johannes Franciscus Buddeus; 25 June 1667, Anklam – 19 November 1729, Gotha) was a German Lutheran theologian and philosopher.

Life

Johann Franz Buddeus was a descendant of the French scholar Guill ...

(1667–1729) a German Lutheran theologian and philosopher; born at Anklam

* Johann Philipp Palthen

Johann Philipp Palthen (26 June 1672 – 26 May 1710) was a Western Pomeranian historian and philologist.

Life

Palthen was born in Wolgast, a port in what was then Swedish Pomerania. His father was Johann Palthen, a senior official at the cou ...

(1672–1710) a Western Pomeranian historian and philologist; born in Wolgast

* Philip Johan von Strahlenberg

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who populariz ...

(1676–1747) a Swedish officer and geographer, contributed to the cartography of Russia; born in Stralsund,

* Johann Joachim Spalding

Johann Joachim Spalding (1 November 1714 – 25 May 1804) was a German Protestant theologian and philosopher of Scottish ancestry who was a native of Tribsees, Swedish Pomerania. He was the father of Georg Ludwig Spalding (1762–1811), a profess ...

(1714–1804) a German Protestant theologian and philosopher of Scottish ancestry; a native of Tribsees

* Aaron Isaac (1730–1817) a Jewish seal engraver and merchant in haberdashery; came from Pommery

* Balthasar Anton Dunker

Balthasar Anton Dunker (15 January 1746, Saal – 2 April 1807, Bern) was a German landscape painter and etcher.

Biography

He was the eldest son of pastor Albert Andreas Duncker (1706–1781) and his second wife, Sophie Dorothea von Olthof ( ...

(1746–1807) a German landscape painter and etcher, born at Saal, near Stralsund.

* Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish German pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified molybdenum, tungsten, barium, hydr ...

(1742-1786) a Swedish Pomeranian and German pharmaceutical chemist; born in Stralsund

* Christian Ehrenfried Weigel

Christian Ehrenfried von Weigel (24 May 1748 – 8 August 1831) was a Swedish-born German scientist and, beginning in 1774, a professor of chemistry, pharmacy, botany, and mineralogy at the University of Greifswald.

Biography

Born in St ...

(1748–1831) a German scientist, professor of Chemistry, Pharmacy, Botany, and Mineralogy at the University of Greifswald; born in Stralsund, died in Griefswald

* Thomas Thorild

Thomas Thorild ( Svarteborg, Bohuslän, 18 April 1759 – Greifswald, Swedish Pomerania, 1 October 1808), was a Swedish poet, critic, feminist and philosopher. He was noted for his early support of women's rights. In his 1793 treatise ''Om kv ...

(1759–1808) a Swedish poet, critic, feminist and philosopher; died at Greifswald

* Ernst Moritz Arndt

Ernst Moritz Arndt (26 December 1769 – 29 January 1860) was a German nationalist historian, writer and poet. Early in his life, he fought for the abolition of serfdom, later against Napoleonic dominance over Germany. Arndt had to flee to Swe ...

(1769–1860) a German nationalist historian, writer and poet; born at Gross Schoritz, now a part of Garz on the island of Rügen

* Caspar David Friedrich

Caspar David Friedrich (5 September 1774 – 7 May 1840) was a 19th-century German Romantic landscape painter, generally considered the most important German artist of his generation. He is best known for his mid-period allegorical landsca ...

(1774–1840) a German Romantic landscape painter; born in Greifswald

* Philipp Otto Runge

Philipp Otto Runge (; 1777–1810) was a German artist, a draftsman, painter, and color theorist. Runge and Caspar David Friedrich are often regarded as the leading painters of the German Romantic movement.Koerner, Joseph Leo. 1990. ''Caspar Dav ...

(1777–1810) a Romantic German painter and draughtsman; born in Wolgast

* Johann Gottfried Ludwig Kosegarten

Johann Gottfried Ludwig Kosegarten (10 September 1792, in Altenkirchen – 18 August 1860, in Greifswald) was a German orientalist born in Altenkirchen on the island of Rügen. He was the son of ecclesiastic Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten (1758– ...

(1792–1860) a German orientalist born in Altenkirchen on the island of Rugen, died in Greifswald

* Georg Friedrich Schömann Georg Friedrich Schömann (28 June 1793 – 25 March 1879), was a German classical scholar of Swedish heritage.Arnold Ruge

Arnold Ruge (13 September 1802 – 31 December 1880) was a German philosopher and political writer. He was the older brother of Ludwig Ruge.

Studies in university and prison

Born in Bergen auf Rügen, he studied in Halle, Jena and Heidelberg. ...

(1802–1880) German philosopher and political writer; born in Bergen auf Rügen

* Johann Karl Rodbertus

Johann Karl Rodbertus (August 12, 1805, Greifswald, Swedish Pomerania – December 6, 1875, Jagetzow), also known as Karl Rodbertus-Jagetzow, was a German economist and socialist and a leading member of the ''Linkes Zentrum'' (centre-left) i ...

(1805–1875) a German economist and socialist of the scientific or conservative school; came from Greifswald

* Adolf Friedrich Stenzler

Adolf Friedrich Stenzler (July 9, 1807 – February 27, 1887) was a German Indologist born in Wolgast.

He initially studied theology and Oriental languages at the University of Greifswald under Johann Gottfried Ludwig Kosegarten (1792–1860), ...

(1807–1887) a German Indologist; born in Wolgast

* Joachim Daniel Andreas Müller (1812–1857) a Swedish gardener and writer; born in Stralsund

;Nobility

* Count Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld (1651–1722) a Swedish Field Marshal; born in Stralsund

*

* Count Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld (1651–1722) a Swedish Field Marshal; born in Stralsund

* Christof Beetz

Christoph Beetz (May 1, 1670, Swedish Pomerania – April 18, 1746, Stralsund) was ennobled by Emperor Charles VI in Vienna, Austria on 27 January 1734 as "Beez von Beezen" (Beetz von Beetzen) after receiving heritable membership of the old class ...

(1670–1746 in Stralsund) Platz-Major and Stabs-Major of the military garrison in Stralsund

* Kurt Christoph, Graf von Schwerin

Kurt Christoph, Graf von Schwerin (26 October 1684 – 6 May 1757) was a Prussian ''Generalfeldmarschall'', one of the leading commanders under Frederick the Great.

Biography

He was born in Löwitz, Pomerania, and at an early age entered the ...

(1684–1757) a Prussian Generalfeldmarschall; born in Löwitz

* Georg Detlev von Flemming (1699–1771) a General in Polish-Saxon service; was born in Iven

* Gustav David Hamilton

Gustav David Hamilton (1699–1788) was a Swedish count and soldier. He was born in 1699 in Barsebäck, Malmöhus County, Sweden. He left Sweden in 1718-1720 to educate himself in warfare in France. In 1720 he became a captain and in 1740 he beca ...

(1699–1788) a Swedish count and soldier; commander of Swedish Pommeranian forces during the Seven Years' War

* Hans Karl von Winterfeldt

Hans Karl von Winterfeldt (4 April 1707 – 8 September 1757), a Prussian general, served in the War of the Polish Succession, the War of Austrian Succession, Frederick the Great's Silesian wars and the Seven Years' War. One of Frederick's ...

(1707–1757) a Prussian general; born at Vanselow Castle, now in Siedenbrünzow

* John Mackenzie, Lord MacLeod (1727–1789) a Scottish Jacobite, soldier of fortune and mercenary

* Curt Bogislaus Ludvig Kristoffer von Stedingk (1746–1837) a Swedish army officer and diplomat

* Bernhard Ditlef von Staffeldt

Bernhard Ditlef von Staffeldt was born on 23 October 1753 in Kenz, Swedish Pomerania, as the son of Lieutenant Bernt von Staffeldt, of Pomeranian nobility, and Catherine Eleonore von Platen. Both his parents died in 1755 while he was still a chil ...

(1753-1818) officer, born in Kenz

* Count Baltzar Bogislaus von Platen (1766–1829) a Swedish naval officer and statesman; born on the island of Rügen

* Friedrich August von Klinkowström (1778–1835) a German artist, author and teacher from an old Pomeranian noble family; born in Ludwigsburg

* Wilhelm Malte I, Prince of Putbus (1783–1854) a German prince, acted as a Swedish governor in Swedish Pomerania; born in Putbus, Rügen

See also

*History of Sweden

The history of Sweden can be traced back to the melting of the Northern Polar Ice Caps. From as early as 12000 BC, humans have inhabited this area. Throughout the Stone Age, between 8000 BC and 6000 BC, early inhabitants used st ...

* Swedish Empire

The Swedish Empire was a European great power that exercised territorial control over much of the Baltic region during the 17th and early 18th centuries ( sv, Stormaktstiden, "the Era of Great Power"). The beginning of the empire is usually ta ...

* Dominions of Sweden

The Dominions of Sweden or ''Svenska besittningar'' ("Swedish possessions") were territories that historically came under control of the Swedish Crown, but never became fully integrated with Sweden. This generally meant that they were ruled by G ...

* Pomerania during the Early Modern Age

References

Footnotes

Sources

* Andreas Önnerfors: ''Svenska Pommern: kulturmöten och identifikation 1720-1815''. Lund, 2003Dissertation written in Swedish available as a PDF file

External links

Foundation for the Swedish Cultural Heritage in Pomerania

at NapoleonSeries.org

at NapoleonSeries.org

at library.ucla.edu {{coord, 54, 05, N, 13, 23, E, type:country_source:kolossus-cawiki, display=title 1630 establishments in Europe 1815 disestablishments in Europe States and territories established in 1630

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

Pomerania

Former states and territories of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

States of the Holy Roman Empire

1630 establishments in the Holy Roman Empire