Swahili coast on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Swahili coast () is a coastal area of

Trade along the Southeastern African coast started as early as the first century CE. Bantu farmers, who are considered the initial settlers within the region, built communities along the coast. These farmers eventually started trading with traders from southeast Asia, southern Arabia, and sometimes Rome and Greece. The rise of the Swahili coast

Trade along the Southeastern African coast started as early as the first century CE. Bantu farmers, who are considered the initial settlers within the region, built communities along the coast. These farmers eventually started trading with traders from southeast Asia, southern Arabia, and sometimes Rome and Greece. The rise of the Swahili coast

Today, Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous region of Tanzania made up of the Zanzibar Archipelago. The archipelago is 25-50 kilometers (16-31 mi) from the mainland. Its main industries are tourism, spice production such as cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and black pepper, and raffia palm trees. In 1698, Zanzibar became part of the Omani sultanate after sultan Saif bin Sultan defeated the Portuguese at Mombasa. In 1832 the sultan of

Today, Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous region of Tanzania made up of the Zanzibar Archipelago. The archipelago is 25-50 kilometers (16-31 mi) from the mainland. Its main industries are tourism, spice production such as cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and black pepper, and raffia palm trees. In 1698, Zanzibar became part of the Omani sultanate after sultan Saif bin Sultan defeated the Portuguese at Mombasa. In 1832 the sultan of

The culture of the Swahili coast had unique characteristics emerging from the diversity of its founders. The Swahili coast was essentially an urban civilization which revolved around trade activities. A few individuals in the Swahili coast were wealthy and made up the elite, ruling class. These elite families were instrumental in the fashioning of Swahili urban life by establishing a Muslim ancestry, embracing Islam, financing mosques in the region, stimulating trade, and practicing the seclusion of women. The majority of the people in the Swahili coast were less wealthy and engaged in such jobs as clerks, craftsmen, sailors, and artisans. The Swahili culture is predominantly Islamic by religion. Archeological records have shown that mosques in the Swahili cities were built as early as the eight century CE. Muslim burial grounds of similar age have also been discovered. Despite being predominantly Muslim, the culture was distinctly African as indicated by the Swahili language used. This language was largely African characterized by many Arab and Persian words. Irrespective of their economic status, the Swahili drew a clear difference between them and the people from interior of the continent whom they considered as uncultured. For the elite, this distinction was important in selling into slavery Africans from neighboring, non-Muslim communities.

The culture of the Swahili coast had unique characteristics emerging from the diversity of its founders. The Swahili coast was essentially an urban civilization which revolved around trade activities. A few individuals in the Swahili coast were wealthy and made up the elite, ruling class. These elite families were instrumental in the fashioning of Swahili urban life by establishing a Muslim ancestry, embracing Islam, financing mosques in the region, stimulating trade, and practicing the seclusion of women. The majority of the people in the Swahili coast were less wealthy and engaged in such jobs as clerks, craftsmen, sailors, and artisans. The Swahili culture is predominantly Islamic by religion. Archeological records have shown that mosques in the Swahili cities were built as early as the eight century CE. Muslim burial grounds of similar age have also been discovered. Despite being predominantly Muslim, the culture was distinctly African as indicated by the Swahili language used. This language was largely African characterized by many Arab and Persian words. Irrespective of their economic status, the Swahili drew a clear difference between them and the people from interior of the continent whom they considered as uncultured. For the elite, this distinction was important in selling into slavery Africans from neighboring, non-Muslim communities.

The primary religion of the Swahili coast is

The primary religion of the Swahili coast is

East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

, bordered by the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

and inhabited by the Swahili people

The Swahili people (, وَسوَحِيلِ) comprise mainly Bantu, Afro-Arab, and Comorian ethnic groups inhabiting the Swahili coast, an area encompassing the East African coast across southern Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and northern Mozambi ...

. It includes Sofala (located in Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

); Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

, Gede, Pate Island, Lamu, and Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban centr ...

(in Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

); and Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (, ; from ) is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of the Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over 7 million people, Dar es Salaam is the largest city in East Africa by population and the ...

and Kilwa (in Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

). In addition, several coastal islands are included in the Swahili coast, such as Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

and Comoros

The Comoros, officially the Union of the Comoros, is an archipelagic country made up of three islands in Southeastern Africa, located at the northern end of the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city is Moroni, ...

.

Areas of what is today considered the Swahili coast were historically known as Azania or Zingion in the Greco-Roman era, and as Zanj or Zinj in Middle Eastern, Indian and Chinese literature from the 7th to the 14th century.A. Lodhi (2000), ''Oriental influences in Swahili: a study in language and culture contacts,'', pp. 72-84 The word "Swahili" means people of the coasts in Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

and is derived from the word ''sawahil'' ("coasts").

The Swahili people and their culture formed from a distinct mix of African and Arab origins. The Swahili were traders and merchants and readily absorbed influences from other cultures. Historical documents including the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

The ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' (), also known by its Latin name as the , is a Greco-Roman world, Greco-Roman periplus written in Koine Greek that describes navigation and Roman commerce, trading opportunities from Roman Egyptian ports lik ...

and works by Ibn Battuta

Ibn Battuta (; 24 February 13041368/1369), was a Maghrebi traveller, explorer and scholar. Over a period of 30 years from 1325 to 1354, he visited much of Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the Iberian Peninsula. Near the end of his life, Ibn ...

describe the society, culture, and economy of the Swahili coast at various points in its history. The Swahili coast has a distinct culture, demography, religion, and geography, and as a result.

History

In the pre-Swahili period, the region was occupied by smaller societies whose main socioeconomic activities were pastoralism, fishing, and mixed farming.LaViolette, Adria. Swahili Coast, In: Encyclopedia of Archaeology, ed. by Deborah M. Pearsall. (2008): 19-21. New York, NY: Academic Press. Early on, those living on the Swahili coast prospered because of agriculture helped by regular yearly rainfall andanimal husbandry

Animal husbandry is the branch of agriculture concerned with animals that are raised for meat, animal fiber, fibre, milk, or other products. It includes day-to-day care, management, production, nutrition, selective breeding, and the raising ...

. The shallow coast was important as it provided seafood. Starting in the early 1st millennium CE, trade was crucial. Submerged river estuaries created natural harbors while yearly monsoons winds helped trade. By the 10th century, ethnic Somalis had settled along the northern Swahili coast, particularly in areas adjacent to the Lamu Archipelago. Later in the 1st millennium there was a migration of Bantu people. The communities settling along the coast shared archaeological and linguistic features with those from the interior of the continent. Archeological data has revealed the use of Kwale and Urewe ceramics both along the coast and within the interior parts, showing that the regions had a shared way of life in the Late Stone and Early Iron Ages.

From the earliest times of which there is any record the African seaboard from the Red Sea to an unknown distance southwards was subject to Arabian influence and dominion. At a later period the coast towns were founded or conquered by Persian and Arabs who, for the most part, fled to Southeast Africa between the 8th and 11th centuries on account of the religious differences of the times, the refugees being schismatics. Various small states thus grew up along the coast. These states are sometimes referred to, collectively, as the Zanj empire. However, it is unlikely that they were ever united under one ruler.

According to Berger et al., this shared way of life began to diverge at least around 13th century CE (362). In the wake of trading activities along the coast, Arab merchants would pour scorn on non-Muslims and some African practices. This attitude of scorn allegedly pushed African elites to deny connections to the interior and to claim descent from Shiraz

Shiraz (; ) is the List of largest cities of Iran, fifth-most-populous city of Iran and the capital of Fars province, which has been historically known as Pars (Sasanian province), Pars () and Persis. As of the 2016 national census, the popu ...

is and to have already converted to Islam. The interactions that ensued led to the formation of the unique Swahili culture and city

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agree ...

states, especially those facilitated by trade.Berger, Eugene, et al. World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500. University of North Georgia Press, 2016.

At the zenith of its power in the 15th century, the Kilwa Sultanate owned or claimed overlordship over the mainland cities of Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban centr ...

, Inhambane and Sofala and the island-states of Mombassa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

, Pemba, Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

, Mafia

"Mafia", as an informal or general term, is often used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the Sicilian Mafia, original Mafia in Sicily, to the Italian-American Mafia, or to other Organized crime in Italy, organiz ...

, Comoro and Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

(plus numerous smaller places).

The voyage of Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama ( , ; – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and nobleman who was the Portuguese discovery of the sea route to India, first European to reach India by sea.

Da Gama's first voyage (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

around the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

into the Indian Ocean in 1498 marked the Portuguese entry into trade, politics, and society in the Indian Ocean world. The Portuguese gained control of the Island of Mozambique and the port city of Sofala in the early 16th century. Vasco da Gama having visited Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

in 1498 was then successful in reaching India thereby permitting the Portuguese to trade with the Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

directly by sea, thus challenging older trading networks of mixed land and sea routes, such as the spice trade

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in t ...

routes that used the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

, Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

and caravans to reach the eastern Mediterranean. Initially, Portuguese rule in Southeast Africa focused mainly on a coastal strip centred in Mombasa. With voyages led by Vasco da Gama, Francisco de Almeida and Afonso de Albuquerque

Afonso de Albuquerque, 1st Duke of Goa ( – 16 December 1515), was a Portuguese general, admiral, statesman and ''conquistador''. He served as viceroy of Portuguese India from 1509 to 1515, during which he expanded Portuguese influence across ...

, the Portuguese dominated much of southeast Africa's coast, including Sofala and Kilwa, by 1515.

The Portuguese were able to wrest much of the coastal trade from Arabs between 1500 and 1700, but, with the Arab seizure of Portugal's key foothold at Fort Jesus

Fort Jesus (Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Forte Jesus de Mombaça'') is a fortification, fort located on Mombasa Island. Designed by the Italian architect Giovanni Battista Cairati, it was built between 1593 and 1596 by order of Felipe I ...

on Mombasa Island

Mombasa Island is a coral outcrop located on Kenya's coast on the Indian Ocean, which is connected to the mainland by a causeway. Part of the city of Mombasa is located on the island, including the Mombasa_Old_Town, Old Town.

History

The old ...

(now in Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

) in 1698 by Omani ruler Saif bin Sultan, the Portuguese retreated to the south.

Omani ruler Said bin Sultan

Sayyid Saïd bin Sultan al-Busaidi (, , ) (5 June 1791 – 19 October 1856) was Sultan of Muscat and Oman, the fifth ruler of the Al Bu Said dynasty from 1804 to 4 June 1856. His rule began after a period of conflict and internecine rivalry of su ...

(1806–1856) moved his court from Muscat

Muscat (, ) is the capital and most populous city in Oman. It is the seat of the Governorate of Muscat. According to the National Centre for Statistics and Information (NCSI), the population of the Muscat Governorate in 2022 was 1.72 million. ...

to Stone Town

Stonetown of Zanzibar (), also known as , is the old part of Zanzibar City, the main city of Zanzibar, in Tanzania. The newer portion of the city is known as Ng'ambo, Swahili for 'the other side'. Stone Town is located on the western coast of Un ...

on the island of Unguja (that is, Zanzibar Island). He established a ruling Arab elite and encouraged the development of clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, ''Syzygium aromaticum'' (). They are native to the Maluku Islands, or Moluccas, in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring, or Aroma compound, fragrance in fin ...

plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

s using the island's slave labour. As a regional commercial power in the 19th century, Oman held the island of Zanzibar and the Zanj region of the Southeast African coast, including Mombasa and Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (, ; from ) is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of the Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over 7 million people, Dar es Salaam is the largest city in East Africa by population and the ...

.

When Said ibn Sultan died in 1856, his sons quarrelled over the succession. As a result of this struggle, the empire was divided in 1861 into two separate principalities: Sultanate of Zanzibar

The Sultanate of Zanzibar (, ), also known as the Zanzibar Sultanate, was an East African Muslim state controlled by the Sultan of Zanzibar, in place between 1856 and 1964. The Sultanate's territories varied over time, and after a period of de ...

and the area of "Muscat and Oman".

Until 1884, the Sultans of Zanzibar controlled a substantial portion of the Swahili Coast, known as Zanj. That year, however, the Society for German Colonization forced local chiefs on the mainland to agree to German protection, prompting Sultan Bargash bin Said to protest. Coinciding with the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

and the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

, further German interest in the area was soon shown in 1885 by the arrival of the newly created German East Africa Company, which had a mission to colonize the area.

In 1886, the British and Germans secretly met and discussed their aims of expansion in the African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes (; ) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. The series includes Lake Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world by area; Lake Tangan ...

, with spheres of influence already agreed upon the year before, with the British to take what would become the East Africa Protectorate (now Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

) and the Germans to take present-day Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

. Both powers leased coastal territory from Zanzibar and established trading stations and outposts. Over the next few years, all of the mainland possessions of Zanzibar came to be administered by European imperial powers, beginning in 1888 when the Imperial British East Africa Company took over administration of Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

.

The same year the German East Africa Company acquired formal direct rule over the coastal area previously submitted to German protection. This resulted in a native uprising, the Abushiri revolt, which was suppressed by the '' Kaiserliche Marine'' and heralded the end of Zanzibar's influence on the mainland.

With the signing of the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty between the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

in 1890, Zanzibar itself became a British protectorate

British protectorates were protectorates under the jurisdiction of the British government. Many territories which became British protectorates already had local rulers with whom the Crown negotiated through treaty, acknowledging their status wh ...

. In August 1896, following the death of Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini, Britain and Zanzibar fought a 38-minute war, the shortest in recorded history. A struggle for succession took place as the Sultan's cousin Khalid bin Barghash seized power. The British instead wanted Hamoud bin Mohammed to become Sultan, believing that he would be much easier to work with. The British gave Khalid an hour to vacate the Sultan's palace in Stone Town. Khalid failed to do so, and instead assembled an army of 2,800 men to fight the British. The British launched an attack on the palace and other locations around the city after which Khalid retreated and later went into exile. Hamoud was then peacefully installed as Sultan.

In 1886, the British government encouraged William Mackinnon, who already had an agreement with the Sultan and whose shipping company traded extensively in the African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes (; ) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. The series includes Lake Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world by area; Lake Tangan ...

, to increase British influence in the region. He formed a British East Africa Association which led to the Imperial British East Africa Company being chartered in 1888 and given the original grant to administer the territory. It administered about of coastline stretching from the River Jubba via Mombasa to German East Africa which were leased from the Sultan. However, the company began to fail, and on 1 July 1895 the British government proclaimed a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

, the East Africa Protectorate, the administration being transferred to the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

.

In 1891, after it became apparent that the German East Africa Company could not handle its dominions, it sold out to the German government, which began to rule German East Africa directly. During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

German East Africa was gradually occupied by forces from the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

and Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

during the East Africa Campaign, although German resistance continued until 1918. After this, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

formalised control of the area by the UK, who renamed it " Tanganyika". The UK held Tanganyika as a League of Nations mandate until the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

after which it was held as a United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

trust territory.

On 23 July 1920, the inland areas of the East Africa Protectorate were annexed as British dominions by Order in Council. That part of the former Protectorate was thereby constituted as the Colony of Kenya

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often o ...

and from that time, the Sultan of Zanzibar ceased to be sovereign over that territory. The remaining wide coastal strip (with the exception of Witu) remained a Protectorate under an agreement with the Sultan of Zanzibar. That coastal strip, remaining under the sovereignty of the Sultan of Zanzibar, was constituted as the Protectorate of Kenya in 1920.Kenya Protectorate Order in Council, 1920 S.R.O. 1920 No. 2343, S.R.O. & S.I. Rev. VIII, 258, State Pp., Vol. 87 p. 968

In 1961, Tanganyika gained its independence from the UK as Tanganyika, joining the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

. It became a republic a year later.

The Colony of Kenya came to an end in 1963 when an ethnic Kenyan majority government was elected for the first time and eventually declared independence.

On 10 December 1963, the Protectorate that had existed over Zanzibar since 1890 was terminated by the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom did not grant Zanzibar independence, as such, because the UK never had sovereignty over Zanzibar. Rather, by the Zanzibar Act 1963 of the United Kingdom, the UK ended the Protectorate and made provision for full-self government in Zanzibar as an independent country within the Commonwealth. Upon the Protectorate being abolished, Zanzibar became a constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

within the Commonwealth under the Sultan. Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah was overthrown a month later during the Zanzibar Revolution

The Zanzibar Revolution (; ) began on 12 January 1964 and led to the overthrow of the Sultan of Zanzibar Jamshid bin Abdullah and his mainly Arab government by the island's majority Black African population.

Zanzibar was an ethnically di ...

. Jamshid fled into exile, and the Sultanate was replaced by the People's Republic of Zanzibar. In April 1964, the existence of this socialist republic was ended with its union with Tanganyika to form the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar

The modern-day African Great Lakes state of Tanzania dates formally from 1964, when it was formed out of the union of the much larger mainland territory of Tanganyika (1961–1964), Tanganyika and the coastal archipelago of Zanzibar. The former w ...

, which became known as Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

six months later.

Indian Ocean trade

Trade along the Southeastern African coast started as early as the first century CE. Bantu farmers, who are considered the initial settlers within the region, built communities along the coast. These farmers eventually started trading with traders from southeast Asia, southern Arabia, and sometimes Rome and Greece. The rise of the Swahili coast

Trade along the Southeastern African coast started as early as the first century CE. Bantu farmers, who are considered the initial settlers within the region, built communities along the coast. These farmers eventually started trading with traders from southeast Asia, southern Arabia, and sometimes Rome and Greece. The rise of the Swahili coast city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

s can be largely attributed to the region's extensive participation in a trade network that spanned the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

. The Indian Ocean's trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

network has been likened to that of the Silk Road

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

, with many destinations being linked through trade. It has been claimed that the Indian Ocean trade network actually connected more people than the Silk Road. The Swahili coast largely exported raw products like timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into uniform and useful sizes (dimensional lumber), including beams and planks or boards. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, window frames). ...

, ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

, animal skins, spices

In the culinary arts, a spice is any seed, fruit, root, Bark (botany), bark, or other plant substance in a form primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of pl ...

, and gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

. Finished products were imported from as far as east Asia such as silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

and porcelain

Porcelain (), also called china, is a ceramic material made by heating Industrial mineral, raw materials, generally including kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The greater strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to oth ...

from China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, spices and cotton

Cotton (), first recorded in ancient India, is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure ...

from India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, and black pepper

Black pepper (''Piper nigrum'') is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit (the peppercorn), which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about in diameter ...

from Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

. Some of the other imports received from Asia and Europe include cottons, silks, woolens, glass and stone beads, metal wire, jewelry, sandalwood, cosmetics, fragrances, kohl, rice, spices, coffee, tea, other foods and flavorings, teak, iron and brass fittings, sailcloth, pottery, porcelain, silver, brass, glass, paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, Textile, rags, poaceae, grasses, Feces#Other uses, herbivore dung, or other vegetable sources in water. Once the water is dra ...

, paints, ink, carved wood, books, carved chests, arms, ammunition, gunpowder, sword

A sword is an edged and bladed weapons, edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter ...

s and dagger

A dagger is a fighting knife with a very sharp point and usually one or two sharp edges, typically designed or capable of being used as a cutting or stabbing, thrusting weapon.State v. Martin, 633 S.W.2d 80 (Mo. 1982): This is the dictionary or ...

s, gold, silver, brass, bronze, religious specialists, and craftsmen. Other places that traded with the Swahili coast include Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

, Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

ia, Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

, Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

, Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

, and Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

. Trade in the region decreased during the Pax Mongolica due to overland trade being cheaper during that period, however, trade by ships provided the advantage that the goods that were transported on them were in bulk, meaning they could be available to the mass market. Many different ethnic groups were involved in the Indian Ocean's trade network, however, especially in the western part of the Indian Ocean, Swahili coast being included, Muslim merchants dominated trade due to their ability to fund the construction of vessels. The yearly monsoon winds carried ships from the Swahili coast to the eastern Indian Ocean and back. These yearly winds were the catalyst for trade in the region as they reduced the risk associated with sailing and made it predictable. The monsoon winds were less strong and reliable as one travelled further South along Africa's coast resulting in settlements being smaller and less frequent towards the South. Trade was further encouraged by the invention of lateen sails which allowed merchants to travel apart from the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

winds. Evidence for Indian Ocean trade includes the presence of pot shards on coastal archaeological sites that can be traced back to China and India.

Slave trade

It has been estimated that between 1450 and 1900 CE as many as 17 million people were sold intoslavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

from Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, and Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

and transported by Asian slave traders through the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, Silk Road

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

, Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

, Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

, and Sahara desert

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

to distant locations. As many as 5 million of these may have come from Africa, though most would have been from West Africa, rather than East Africa. Before the 18th Century, the slave trade on the Southeast African coast was fairly minor. Women and children were preferred since the main roles of enslaved persons in the Asian World were as domestic servants and concubines. Most of the enslaved would have been absorbed into Swahili households. The children of enslaved concubines were born as free members of their father's lineage without distinction and manumissions were a common act of piety for elderly Muslims.

A series of slave uprisings took place between 869 and 883 CE in Basra

Basra () is a port city in Iraq, southern Iraq. It is the capital of the eponymous Basra Governorate, as well as the List of largest cities of Iraq, third largest city in Iraq overall, behind Baghdad and Mosul. Located near the Iran–Iraq bor ...

, a city of present-day Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, referred to as the Zanj Rebellion. The enslaved Zanj were likely transported from the more southern areas of Southeast Africa. The uprising grew to more than 500,000 slaves and free men as well, who were used in strenuous agriculture labor. The Zanj Rebellion

The Zanj Rebellion ( ) was a major revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate, which took place from 869 until 883. Begun near the city of Basra in present-day southern Iraq and led by one Ali ibn Muhammad, the insurrection involved both enslaved and ...

was a guerilla war mounted by slaves against the Abbasids. This revolt lasted 14 years. Slaves with numbers as high as 15,000 would raid towns, set slaves free, and seize weapons and food. These revolts greatly destabilized the grip that the Abbasids had over slaves. During the Rebellion, the slaves, under the leadership of Ali ibn Muhammad, captured Basra and even threatened to raid the capital, Baghdad. The vast majority of the slave rebels were Black Africans, and the 9th century Zanj revolts in Iraq is some of the best evidence of a large number of people being sold into slavery from Southeastern Africa. As a result of this uprising, Abbasid Caliphate largely abandoned the large-scale importation of slaves from Southeast Africa.

Coins

On the Swahili coast, coin minting can be correlated to an increase in Indian Ocean trade. The earliest coins share many similarities to coins fromSindh

Sindh ( ; ; , ; abbr. SD, historically romanized as Sind (caliphal province), Sind or Scinde) is a Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Pakistan. Located in the Geography of Pakistan, southeastern region of the country, Sindh is t ...

. Some estimate that coins were minted on the Swahili coast as early as the mid 9th century until the end of the 15th century CE. The making of coins came comparatively late to this area with many other cultures starting to make coins several centuries earlier. There are archaeological records of foreign coins being used in the area but few coins of foreign origin have been excavated. Previously, it was believed that the coins from the Swahili coast were of Persian origin, but now it is recognized that these are in fact indigenous coins. The coins found on the coast only have inscriptions in Arabic, not Swahili. The coins from this region can be put into five categories: Shanga silver, Tanzanian silver, Kilwa copper, Kilwa gold and Zanzibar copper. Silver is not found locally on the Swahili coast, so the metal had to be imported.

Coastal islands

There are manyisland

An island or isle is a piece of land, distinct from a continent, completely surrounded by water. There are continental islands, which were formed by being split from a continent by plate tectonics, and oceanic islands, which have never been ...

s close to the Swahili coast including Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

, Kilwa, Mafia

"Mafia", as an informal or general term, is often used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the Sicilian Mafia, original Mafia in Sicily, to the Italian-American Mafia, or to other Organized crime in Italy, organiz ...

and Lamu in addition to distant Comoros

The Comoros, officially the Union of the Comoros, is an archipelagic country made up of three islands in Southeastern Africa, located at the northern end of the Mozambique Channel in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city is Moroni, ...

which is sometimes considered part of the Swahili coast. Several of these islands became very powerful through trade including Zanzibar and Kilwa. Before these islands became trade hubs, it is likely that the abundant local resources were very important to the islands' inhabitants. These resources include mangroves, fishing, and crustaceans. Mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows mainly in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. Mangroves grow in an equatorial climate, typically along coastlines and tidal rivers. They have particular adaptations to take in extra oxygen a ...

s were important as they provided wood for boats. However, archaeological digs reveal that the culture of the Swahili people living on these islands was adapted to trade and their maritime surroundings quite early on.

Kilwa

Although today Kilwa is in ruins, historically it was one of the most powerful city states on the Swahili coast. One of the main exports along the Swahili coast was gold and in the 13th century the city of Kilwa took control of the gold trade from Banadir in modern-day Somalia. By the mid-14th century the sultan of Kilwa was able to assert his power over several other city states. Kilwa levied a customs duty on the gold that was shipped north fromZimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

that stopped in Kilwa's port. In Kilwa's Husuni Kabwa, or Great Fort, there is evidence of gardens, a pool, and commercial activities. The fort served as a palace and area to store commercial goods and was built by sultan Al-Hasan Ibn Suleman. The fort consists of a public courtyard, and a private area. Due to the intricate architecture present in Kilwa Ibn Battuta

Ibn Battuta (; 24 February 13041368/1369), was a Maghrebi traveller, explorer and scholar. Over a period of 30 years from 1325 to 1354, he visited much of Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the Iberian Peninsula. Near the end of his life, Ibn ...

, a Moroccan explorer, described the town as "one of the most beautiful towns in the world." Although Kilwa had been trading for centuries, the city's wealth and control of the gold trade attracted the Portuguese who were in search of gold. During the period of Portuguese subjugation, trade essentially stopped in Kilwa.

Zanzibar

Today, Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous region of Tanzania made up of the Zanzibar Archipelago. The archipelago is 25-50 kilometers (16-31 mi) from the mainland. Its main industries are tourism, spice production such as cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and black pepper, and raffia palm trees. In 1698, Zanzibar became part of the Omani sultanate after sultan Saif bin Sultan defeated the Portuguese at Mombasa. In 1832 the sultan of

Today, Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous region of Tanzania made up of the Zanzibar Archipelago. The archipelago is 25-50 kilometers (16-31 mi) from the mainland. Its main industries are tourism, spice production such as cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and black pepper, and raffia palm trees. In 1698, Zanzibar became part of the Omani sultanate after sultan Saif bin Sultan defeated the Portuguese at Mombasa. In 1832 the sultan of Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

moved his capital from Muscat to Stone Town, the main city of the Zanzibar archipelago. He encouraged the creation of clove plantations as well as the settlement of Indian traders. Until 1890 the sultans of Zanzibar controlled part of the Swahili coast known as Zanj which included Mombasa and Dar es Salaam. At the end of the 19th century, the British and German empires brought Zanzibar into their spheres of influence.

Culture

The culture of the Swahili coast had unique characteristics emerging from the diversity of its founders. The Swahili coast was essentially an urban civilization which revolved around trade activities. A few individuals in the Swahili coast were wealthy and made up the elite, ruling class. These elite families were instrumental in the fashioning of Swahili urban life by establishing a Muslim ancestry, embracing Islam, financing mosques in the region, stimulating trade, and practicing the seclusion of women. The majority of the people in the Swahili coast were less wealthy and engaged in such jobs as clerks, craftsmen, sailors, and artisans. The Swahili culture is predominantly Islamic by religion. Archeological records have shown that mosques in the Swahili cities were built as early as the eight century CE. Muslim burial grounds of similar age have also been discovered. Despite being predominantly Muslim, the culture was distinctly African as indicated by the Swahili language used. This language was largely African characterized by many Arab and Persian words. Irrespective of their economic status, the Swahili drew a clear difference between them and the people from interior of the continent whom they considered as uncultured. For the elite, this distinction was important in selling into slavery Africans from neighboring, non-Muslim communities.

The culture of the Swahili coast had unique characteristics emerging from the diversity of its founders. The Swahili coast was essentially an urban civilization which revolved around trade activities. A few individuals in the Swahili coast were wealthy and made up the elite, ruling class. These elite families were instrumental in the fashioning of Swahili urban life by establishing a Muslim ancestry, embracing Islam, financing mosques in the region, stimulating trade, and practicing the seclusion of women. The majority of the people in the Swahili coast were less wealthy and engaged in such jobs as clerks, craftsmen, sailors, and artisans. The Swahili culture is predominantly Islamic by religion. Archeological records have shown that mosques in the Swahili cities were built as early as the eight century CE. Muslim burial grounds of similar age have also been discovered. Despite being predominantly Muslim, the culture was distinctly African as indicated by the Swahili language used. This language was largely African characterized by many Arab and Persian words. Irrespective of their economic status, the Swahili drew a clear difference between them and the people from interior of the continent whom they considered as uncultured. For the elite, this distinction was important in selling into slavery Africans from neighboring, non-Muslim communities. Fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

and shellfish

Shellfish, in colloquial and fisheries usage, are exoskeleton-bearing Aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrates used as Human food, food, including various species of Mollusca, molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish ...

are common in the Swahili coast's food due to its proximity and reliance on the coast. In addition, coconut

The coconut tree (''Cocos nucifera'') is a member of the palm tree family (biology), family (Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus ''Cocos''. The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut") can refer to the whole coconut palm, ...

s and many different spice

In the culinary arts, a spice is any seed, fruit, root, Bark (botany), bark, or other plant substance in a form primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of pl ...

s as well as tropical fruits are often used. The Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

influence can be seen in the small cups of coffee that are available in the area and the sweet meats that can be tasted. The Arab influence is also seen in the Swahili language, architecture, and boat design including food as aforementioned.

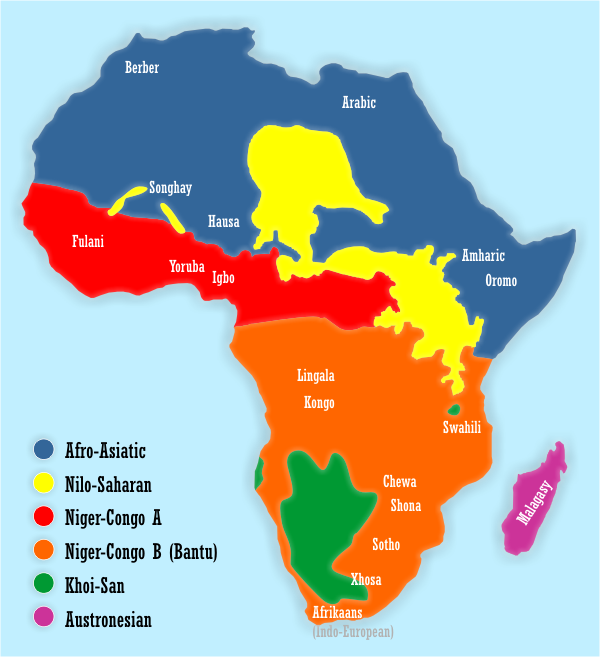

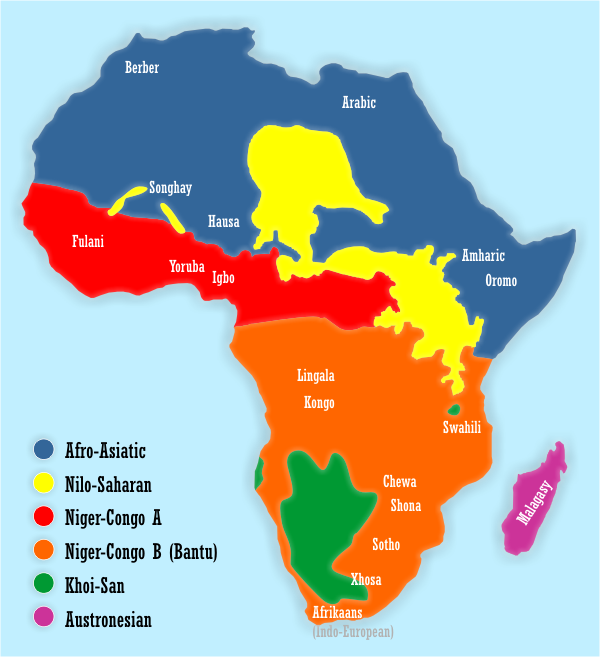

Language

Swahili is thelingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, link language or language of wider communication (LWC), is a Natural language, language systematically used to make co ...

of Southeast Africa and the national language of Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

and Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

in addition to being one of the languages of the African Union. Estimates of the number of speakers vary greatly but are usually around 50, 80 and 100 million people. Swahili is a Bantu language with heavy influence from Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

with the word "Swahili" itself descending from the Arabic word "sahil," meaning "coast"; "Swahili" meaning "people of the coast." Some hold that Swahili is a completely Bantu language with only a few Arabic loanword

A loanword (also a loan word, loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language (the recipient or target language), through the process of borrowing. Borrowing is a metaphorical term t ...

s, while others suggest that Bantu and Arabic mixed to form Swahili. It has been hypothesized that the mixing of languages was facilitated by intermarriage between natives and Arabs

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of yea ...

in addition to general interactions. Most likely, Swahili was around in some form before Arab contact but then was heavily influenced. Swahili syntax is very similar to that of other Bantu languages as, like other Bantu languages, Swahili has five vowels (a,e,i,o,u).

Religion

The primary religion of the Swahili coast is

The primary religion of the Swahili coast is Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

. Initially, unorthodox Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

fleeing persecution in their homelands may have settled in the region, but it is likely that the religion took hold through Arab traders. The majority of Muslims on the Swahili coast are Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

, but many people continue non-Islamic traditions. For example, spirits who bring illness and misfortune are appeased and people are buried with valuable items. In addition, teachers of Islam are allowed to become medicine men; having medicine men being a practice carried over from local tribal religions. Men wear protective amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word , which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects a perso ...

s with Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

verses. The historian P. Curtis said about Islam and the Swahili coast, "The Muslim religion ultimately became one of the central elements of Swahili identity."

Architecture

The earliest knownMosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

s on the Swahili coast were built of wood and date back to the 9th century CE. Swahili Mosques are typically smaller than elsewhere in the Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

and have little decorations. In addition, they typically do not have minaret

A minaret is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generally used to project the Muslim call to prayer (''adhan'') from a muezzin, but they also served as landmarks and symbols of Islam's presence. They can h ...

s or inner courtyards. Domestic housing was usually constructed of mud-bricks and were mostly one storey high. Often, they had two long and narrow rooms. Housing is often decorated by carved door frames and window grilles. Larger houses sometimes have gardens and orchards. Houses were constructed close together which resulted in twisty narrow streets.

See also

* Kilwa Sultanate (10th-16th c.), today in Tanzania *Mayotte

Mayotte ( ; , ; , ; , ), officially the Department of Mayotte (), is an Overseas France, overseas Overseas departments and regions of France, department and region and single territorial collectivity of France. It is one of the Overseas departm ...

, French territory; islands NW of Madagascar

* Omani Empire

The Omani Empire () was a maritime empire, vying with Portugal and Britain for trade and influence in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. After rising as a regional power in the 18th century, the empire at its peak in the 19th century saw its i ...

, Oman and Zanzibar region

* Shirazi people, Bantus inhabiting the Swahili coast

* Swahili culture

** Swahili architecture

* Zanj, part of E African coast

** Sea of Zanj

The Sea of Zanj (; ) is a former name for the portion of the western Indian Ocean adjacent to the region in the African Great Lakes referred to by medieval Arab geographers as Zanj.

, part of W Indian Ocean

References

{{Regions of the world Historical regions Southeast Africa Cultural regions Coasts of the Indian Ocean Islam and slavery Regions of Africa Geography of Cabo Delgado Province Slavery in Oman Zanzibar slave trade