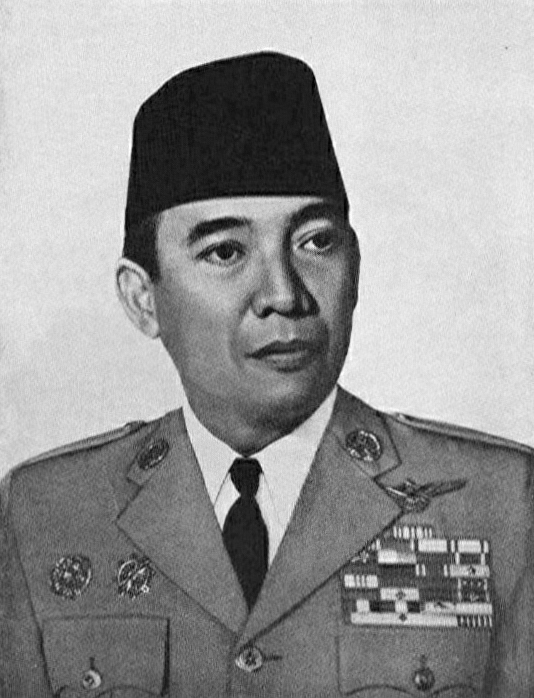

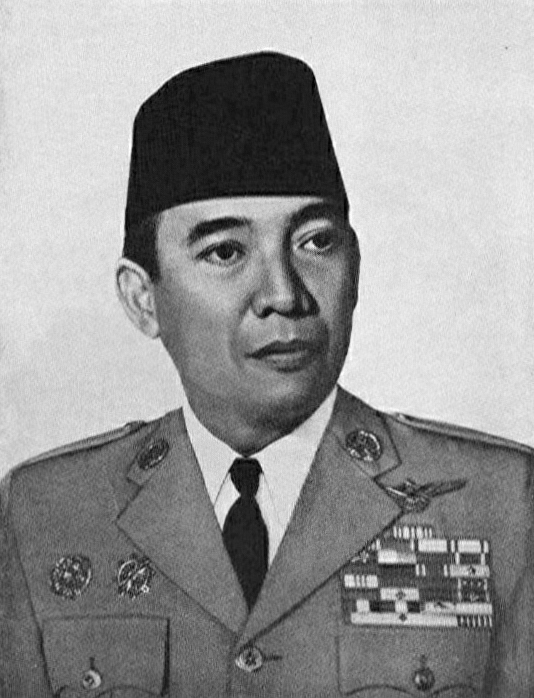

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an

Indonesian statesman

A statesman or stateswoman typically is a politician who has had a long and respected political career at the national or international level.

Statesman or Statesmen may also refer to:

Newspapers United States

* ''The Statesman'' (Oregon), a ...

,

orator,

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

, and

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

who was the first

president of Indonesia

The President of the Republic of Indonesia ( id, Presiden Republik Indonesia) is both the head of state and the head of government of the Republic of Indonesia. The president leads the executive branch of the Indonesian government an ...

, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of the Indonesian struggle for independence from the

Dutch colonialists. He was a prominent leader of

Indonesia's nationalist movement during the

colonial period and spent over a decade under Dutch detention until released by the

invading Japanese forces in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Sukarno and his fellow nationalists

collaborated to garner support for the Japanese war effort from the population, in exchange for Japanese aid in spreading nationalist ideas. Upon

Japanese surrender, Sukarno and

Mohammad Hatta declared Indonesian independence on 17 August 1945, and Sukarno was appointed president. He led the

Indonesian resistance to Dutch re-colonisation efforts via diplomatic and military means until the

Dutch recognition of Indonesian independence in 1949. Author

Pramoedya Ananta Toer once wrote, "Sukarno was the only Asian leader of the modern era able to unify people of such differing ethnic, cultural and religious backgrounds without shedding a drop of blood."

After

a chaotic period of

parliamentary democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of t ...

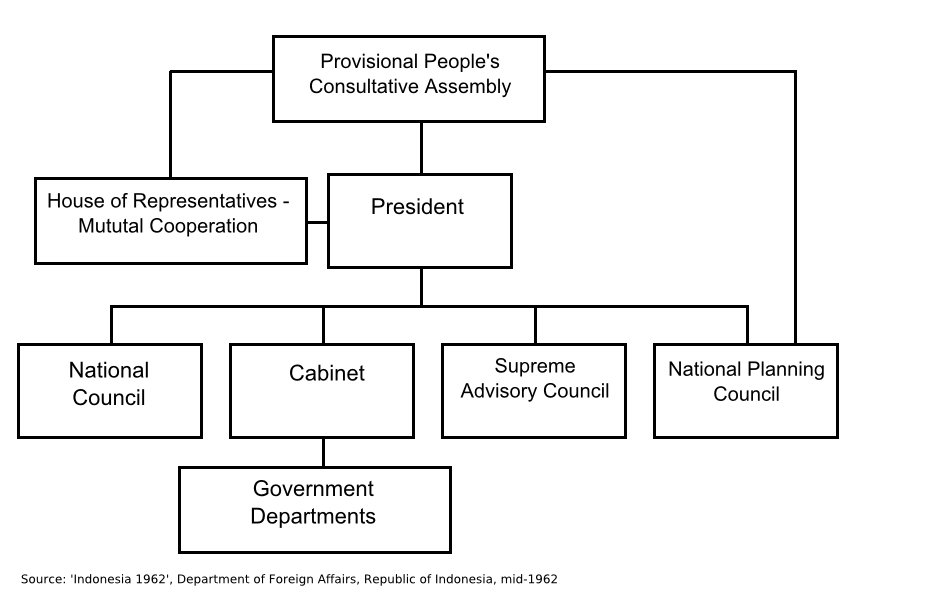

, Sukarno established an autocratic system called "

Guided Democracy

Guided democracy, also called managed democracy, is a formally democratic government that functions as a ''de facto'' authoritarian government or in some cases, as an autocratic government. Such hybrid regimes are legitimized by elections that ...

" in 1959 that successfully ended the instability and rebellions which were threatening the survival of the diverse and fractious country. In the early 1960s Sukarno embarked on a series of aggressive foreign policies under the rubric of

anti-imperialism

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic ...

and personally championed the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

. These developments led to increasing friction with the West and closer relations with the USSR. After the events surrounding the

30 September Movement of 1965, the military general

Suharto largely took control of the country in a Western backed military overthrow of the Sukarno-led government. This was followed by repression of real and perceived leftists, including

executions of Communist party members and suspected sympathisers in several massacres with support from the

CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

and

British intelligence services, resulting in an estimated 500,000 to over 1,000,000 deaths.

[Mark Aarons (2007).]

Justice Betrayed: Post-1945 Responses to Genocide

" In David A. Blumenthal and Timothy L. H. McCormack (eds).

The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence or Institutionalised Vengeance? (International Humanitarian Law).

'' Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p.&nbs

80

[The Memory of Savage Anticommunist Killings Still Haunts Indonesia, 50 Years On]

''Time'' In 1967, Suharto officially

assumed the presidency, replacing Sukarno, who remained under house arrest until his death in 1970.

Name

The name was derived from a hero in the ''

Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; sa, महाभारतम्, ', ) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India in Hinduism, the other being the '' Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the K ...

'' Hindu epic,

Karna

Karna (Sanskrit: कर्ण, IAST: ''Karṇa''), also known as Vasusena, Anga-raja, and Radheya, is one of the main protagonists of the Hindu epic '' Mahābhārata''. He is the son of the sun god Surya and princess Kunti (mother of the ...

. His father being from Indonesia was inspired by Indian historical heroes and Hindu culture and was deeply influenced by

Karna

Karna (Sanskrit: कर्ण, IAST: ''Karṇa''), also known as Vasusena, Anga-raja, and Radheya, is one of the main protagonists of the Hindu epic '' Mahābhārata''. He is the son of the sun god Surya and princess Kunti (mother of the ...

that he named his son as Sukarno. Su(good)+ Karna or "The good Karna". Karna was a main hero of the great epic Mahabharata and Sukarno's father projected him to grow up a brave person like Karna, become Daanveer for his subjects, savior or the messiah for his people and a king like

Karna

Karna (Sanskrit: कर्ण, IAST: ''Karṇa''), also known as Vasusena, Anga-raja, and Radheya, is one of the main protagonists of the Hindu epic '' Mahābhārata''. He is the son of the sun god Surya and princess Kunti (mother of the ...

. The spelling Soekarno, based on

Dutch orthography, is still in frequent use, mainly because he signed his name in the old spelling. Sukarno himself insisted on a "u" in writing, not "oe", but said that he had been told in school to use the Dutch style, and that after 50 years, it was too difficult to change his signature, so still spelled his signature with "oe". Official Indonesian presidential decrees from the period 1947–1968, however, printed his name using the 1947 spelling. The

Soekarno–Hatta International Airport, which serves the area near Indonesia's capital,

Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

, still uses the Dutch spelling.

Indonesians also remember him as ''Bung'' Karno (Brother/Comrade Karno) or ''Pak'' Karno ("Mr. Karno"). Like many

Javanese people, he had

only one name.

[In Search of Achmad Sukarno](_blank)

Steven Drakeley, University of Western Sydney

He is sometimes referred to in foreign accounts as "Achmed Sukarno", or some variation thereof. The fictitious first name may have been added by Western journalists confused over someone with just a single name, or by Indonesian supporters of independence to attract support from Muslim countries.

Source from Ministry of Foreign Affairs later revealed, "Achmed" (later, written as "Ahmad" or "Ahmed" by Arabian states and other foreign state press) was coined by M. Zein Hassan, an Indonesian student at

Al-Azhar University

, image = جامعة_الأزهر_بالقاهرة.jpg

, image_size = 250

, caption = Al-Azhar University portal

, motto =

, established =

*970/972 first foundat ...

and later a member of the staff at the Department of Foreign Affairs, to establish Soekarno's identity as a Muslim to the Egyptian press after a brief controversy at that time in Egypt alleging Sukarno's name was "not Muslim enough". After adopting the name "Achmed" Muslim and Arab states freely supported Sukarno. Thus, in correspondence with the Middle East, Sukarno always signed his name as "Achmed Soekarno."

Early life

Early life and education

Early life

The son of a Javanese primary school teacher, an

aristocrat named

Raden Soekemi Sosrodihardjo, and his Hindu Balinese wife from the Brahmin family named

Ida Ayu Nyoman Rai from

Buleleng

Buleleng ( ban, ᬓᬩᬸᬧᬢᬾᬦ᭄ᬩᬸᬮᭂᬮᭂᬂ, Kabupatén Buléléng) is a regency (''kabupaten'') of Bali, Indonesia. It has an area of 1,365.88 km2 and population of 624,125 at the 2010 census and 791,910 at the 2020 cen ...

, Sukarno was born in

Surabaya

Surabaya ( jv, ꦱꦸꦫꦧꦪ or jv, ꦯꦹꦫꦨꦪ; ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of East Java and the second-largest city in Indonesia, after Jakarta. Located on the northeastern border of Java island, on the M ...

in the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

(now Indonesia), where his father had been sent following an application for a transfer to Java. He was originally named Kusno Sosrodihardjo. Following

Javanese custom, he was renamed after surviving a childhood illness.

Education

After graduating from a native primary school in 1912, he was sent to the ''Europeesche Lagere School'' (a Dutch primary school) in

Mojokerto. Subsequently, in 1916, Sukarno went to a ''

Hogere Burgerschool'' (a Dutch type higher level secondary school) in

Surabaya

Surabaya ( jv, ꦱꦸꦫꦧꦪ or jv, ꦯꦹꦫꦨꦪ; ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of East Java and the second-largest city in Indonesia, after Jakarta. Located on the northeastern border of Java island, on the M ...

, where he met

Tjokroaminoto, a nationalist and founder of

Sarekat Islam. In 1920, Sukarno married

Tjokroaminoto's daughter Siti Oetari. In 1921, he began to study

civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewa ...

(with a focus on

architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

) at the ''

Technische Hoogeschool te Bandoeng

The Bandung Institute of Technology ( id, Institut Teknologi Bandung, abbreviated as ITB) is a national research university located in Bandung, Indonesia. Since its establishment in 1920, ITB has been consistently recognized as Indonesia's premie ...

'' (Bandoeng Institute of Technology), where he obtained an

Ingenieur degree (abbreviated as "ir.", a Dutch type

engineer's degree

An engineer's degree is an advanced academic degree in engineering which is conferred in Europe, some countries of Latin America, North Africa and a few institutions in the United States. The degree may require a thesis but always requires a non-a ...

) in 1926. During his study in

Bandung

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

, Sukarno became romantically involved with Inggit Garnasih, the wife of Sanoesi, the owner of the boarding house where he lived as a student. Inggit was 13 years older than Sukarno. In March 1923, Sukarno divorced Siti Oetari to marry Inggit (who also divorced her husband Sanoesi). Sukarno later divorced Inggit and married Fatmawati.

Atypically even among the country's small educated elite, Sukarno was fluent in several languages. In addition to the

Javanese language

Javanese (, , ; , Aksara Jawa: , Pegon: , IPA: ) is a Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the Javanese people from the central and eastern parts of the island of Java, Indonesia. There are also pockets of Javanese speakers on the nort ...

of his childhood, he was a master of

Sundanese,

Balinese and

Indonesian, and was especially strong in Dutch. He was also quite comfortable in

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, English,

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

,

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

, and

Japanese, all of which were taught at his HBS. He was helped by his

photographic memory and

precocious mind.

In his studies, Sukarno was "intensely modern", both in architecture and in politics. He despised both the traditional Javanese

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

, which he considered "backward" and to blame for the fall of the country under Dutch occupation and exploitation, and the

imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic powe ...

practised by

Western countries, which he termed as "exploitation of humans by other humans" (''exploitation de l'homme par l'homme''). He blamed this for the deep poverty and low levels of education of Indonesian people under the Dutch. To promote nationalistic pride amongst Indonesians, Sukarno interpreted these ideas in his dress, in his urban planning for the capital (eventually

Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

), and in his

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

politics, though he did not extend his taste for modern art to

pop music

Pop music is a genre of popular music that originated in its modern form during the mid-1950s in the United States and the United Kingdom. The terms ''popular music'' and ''pop music'' are often used interchangeably, although the former descri ...

; he had

Koes Bersaudara

Koes Plus, formerly Koes Bersaudara (Koes Brothers), is an Indonesian musical group that enjoyed success in the 1960s and 1970s. Known as one of Indonesia's classic musical acts, the band peaked in popularity in the days far before the advent of ...

imprisoned for their allegedly decadent lyrics despite his reputation for womanising. For Sukarno, modernity was blind to race, neat and elegant in style, and anti-imperialist.

Architectural career

Sukarno & Anwari firm

After graduation in 1926, Sukarno and his university friend Anwari established the architectural firm Sukarno & Anwari in

Bandung

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

, which provided planning and contractor services. Among Sukarno's architectural works are the renovated building of the Preanger Hotel (1929), where he acted as assistant to famous Dutch architect

Charles Prosper Wolff Schoemaker

Charles Prosper Wolff Schoemaker (25 July 1882 – 22 May 1949) was a Dutch architect who designed several distinguished Art Deco buildings in Bandung, Indonesia, including the Villa Isola and Hotel Preanger. He has been described as "the Fran ...

. Sukarno also designed many private houses on today's Jalan Gatot Subroto, Jalan Palasari, and Jalan Dewi Sartika in

Bandung

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

. Later on, as president, Sukarno remained engaged in architecture, designing the Proclamation Monument and adjacent ''Gedung Pola'' in

Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

; the Youth Monument (''Tugu Muda'') in

Semarang

Semarang ( jv, ꦏꦸꦛꦯꦼꦩꦫꦁ , Pegon: سماراڠ) is the capital and largest city of Central Java province in Indonesia. It was a major port during the Dutch colonial era, and is still an important regional center and port today ...

; the Alun-alun Monument in

Malang

Malang (; ) is a landlocked city in the Indonesian province of East Java. It has a history dating back to the age of Singhasari Kingdom. It is the second most populous city in the province, with a population of 820,043 at the 2010 Census and ...

; the Heroes' Monument in

Surabaya

Surabaya ( jv, ꦱꦸꦫꦧꦪ or jv, ꦯꦹꦫꦨꦪ; ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of East Java and the second-largest city in Indonesia, after Jakarta. Located on the northeastern border of Java island, on the M ...

; and also the new city of

Palangkaraya

Palangka Raya is the capital and largest city of the Indonesian province of Central Kalimantan. The city is situated between the Kahayan and the Sabangau rivers on the island of Borneo. As of the 2020 census, the city has a population of 293,50 ...

in

Central Kalimantan.

Early independence struggle

Sukarno was first exposed to nationalist ideas while living under

Oemar Said Tjokroaminoto. Later, while a student in

Bandung

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

, he immersed himself in European, American, Nationalist, communist, and religious political philosophy, eventually developing his own political ideology of Indonesian-style socialist self-sufficiency. He began styling his ideas as

Marhaenism, named after Marhaen, an Indonesian peasant he met in southern Bandung area, who owned his little plot of land and worked on it himself, producing sufficient income to support his family. In university, Sukarno began organising a study club for Indonesian students, the ''Algemeene Studieclub'', in opposition to the established student clubs dominated by Dutch students.

Involvement in the Indonesian National Party

On 4 July 1927, Sukarno with his friends from the ''Algemeene Studieclub'' established a pro-independence party, the

Indonesian National Party (PNI), of which Sukarno was elected the first leader. The party advocated independence for Indonesia, and opposed imperialism and capitalism because it opined that both systems worsened the life of Indonesian people. The party also advocated

secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a si ...

and unity amongst the many different ethnicities in the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

, to establish a united Indonesia. Sukarno also hoped that Japan would commence a war against the western powers and that Java could then gain its independence with Japan's aid. Coming soon after the disintegration of

Sarekat Islam in the early 1920s and the crushing of the

Indonesian Communist Party

The Communist Party of Indonesia (Indonesian: ''Partai Komunis Indonesia'', PKI) was a communist party in Indonesia during the mid-20th century. It was the largest non-ruling communist party in the world before its violent disbandment in 1965 ...

after its failed rebellion of 1926, the PNI began to attract a large number of followers, particularly among the new university-educated youths eager for broader freedoms and opportunities denied to them in the racist and constrictive political system of Dutch colonialism.

Arrest, trial, and imprisonment

Arrest and trial

PNI activities came to the attention of the colonial government, and Sukarno's speeches and meetings were often infiltrated and disrupted by agents of the colonial secret police (''Politieke Inlichtingen Dienst''/PID). Eventually, Sukarno and other key PNI leaders were arrested on 29 December 1929 by Dutch colonial authorities in a series of raids throughout Java. Sukarno himself was arrested while on a visit to

Yogyakarta. During his trial at the Bandung ''Landraad'' courthouse from August to December 1930, Sukarno made a series of long political speeches attacking colonialism and imperialism, titled ''Indonesia Menggoegat'' (''

Indonesia Accuses'').

Sentence and imprisonment

In December 1930, Sukarno was sentenced to four years in prison, which were served in Sukamiskin prison in Bandung. His speech, however, received extensive coverage by the press, and due to strong pressure from the liberal elements in both Netherlands and

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

, Sukarno was released early on 31 December 1931. By this time, he had become a popular hero widely known throughout Indonesia.

However, during his imprisonment, the PNI had been splintered by the oppression of colonial authorities and internal dissension. The original PNI was disbanded by the Dutch, and its former members formed two different parties; the

Indonesia Party (Partindo) under Sukarno's associate

Sartono

Sartono (5 August 1900 – 15 October 1968) was an Indonesian politician and lawyer who served as the first speaker of the People's Representative Council (DPR) from 1950 until 1960. Born to a noble ethnic- Javanese family, Sartono studied ...

who were promoting mass agitation, and the Indonesian Nationalist Education (New PNI) under

Mohammad Hatta and

Soetan Sjahrir

Sutan Sjahrir (5 March 1909 – 9 April 1966) was an Indonesian politician, and revolutionary independence leader, who served as the first Prime Minister of Indonesia, from 1945 until 1947. Previously, he was a key Indonesian nationalist organiz ...

, two nationalists who recently returned from studies in the Netherlands, and who were promoting a long-term strategy of providing modern education to the uneducated Indonesian populace to develop an intellectual elite able to offer effective resistance to Dutch rule. After attempting to reconcile the two parties to establish one united nationalist front, Sukarno chose to become the head of Partindo on 28 July 1932. Partindo had maintained its alignment with Sukarno's own strategy of immediate mass agitation, and Sukarno disagreed with Hatta's long-term cadre-based struggle. Hatta himself believed Indonesian independence would not occur within his lifetime, while Sukarno believed Hatta's strategy ignored the fact that politics can only make real changes through formation and utilisation of force (''machtsvorming en machtsaanwending'').

During this period, to support himself and the party financially, Sukarno returned to architecture, opening the bureau of Soekarno & Roosseno with his university junior

Roosseno. He also wrote articles for the party's newspaper, ''Fikiran Ra'jat''. While based in Bandung, Sukarno travelled extensively throughout Java to establish contacts with other nationalists. His activities attracted further attention by the Dutch PID. In mid-1933, Sukarno published a series of writings titled ''Mentjapai Indonesia Merdeka'' ("To Attain Independent Indonesia"). For this writing, he was arrested by Dutch police while visiting fellow nationalist

Mohammad Hoesni Thamrin

Mohammad Husni Thamrin (16 February 1894 – 11 January 1941) was a pre-independence Indonesian political thinker and nationalist who after his death was named a National Hero.

Early life and beginning of political career

Thamrin was born ...

in Jakarta on 1 August 1933.

Exile

This time, to prevent providing Sukarno with a platform to make political speeches, the hardline governor-general

Jonkheer

(female equivalent: ; french: Écuyer; en, Squire) is an honorific in the Low Countries denoting the lowest rank within the nobility. In the Netherlands, this in general concerns a prefix used by the untitled nobility. In Belgium, this is the ...

Bonifacius Cornelis de Jonge utilised his emergency powers to send Sukarno to internal exile without trial. In 1934, Sukarno was shipped, along with his family (including Inggit Garnasih), to the remote town of

Ende, on the island of

Flores

Flores is one of the Lesser Sunda Islands, a group of islands in the eastern half of Indonesia. Including the Komodo Islands off its west coast (but excluding the Solor Archipelago to the east of Flores), the land area is 15,530.58 km2, and t ...

. During his time in Flores, he utilised his limited freedom of movement to establish a children's theatre. Among its members was future politician

Frans Seda. Due to an outbreak of malaria in Flores, the Dutch authorities decided to move Sukarno and his family to

Bencoolen (now Bengkulu) on the western coast of

Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

, in February 1938.

In

Bengkulu, Sukarno became acquainted with Hassan Din, the local head of

Muhammadiyah organisation, and he was allowed to teach religious teachings at a local school owned by the

Muhammadiyah. One of his students was 15-year-old

Fatmawati, daughter of Hassan Din. He became romantically involved with Fatmawati, which he justified by stating the inability of Inggit Garnasih to produce children during their almost 20-year marriage. Sukarno was still in Bengkulu exile when the Japanese

invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

the archipelago in 1942.

World War II and the Japanese occupation

Japanese occupation

Background and Invasion

In early 1929, during the

Indonesian National Revival, Sukarno and fellow Indonesian nationalist leader

Mohammad Hatta (later

Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

), first foresaw a Pacific War and the opportunity that a Japanese advance on Indonesia might present for the Indonesian independence cause. In February 1942,

Imperial Japan invaded the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

quickly defeating Dutch forces who marched, bussed and trucked Sukarno and his entourage three hundred kilometres from

Bengkulu to

Padang,

Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

. They intended keeping him prisoner and shipping him to Australia but abruptly abandoned him to save themselves upon the impending approach of Japanese forces on Padang.

Cooperation with the Japanese

The Japanese had their own files on Sukarno, and the Japanese commander in

Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

approached him with respect, wanting to use him to organise and pacify the Indonesians. Sukarno, on the other hand, wanted to use the Japanese to gain independence for Indonesia: "The Lord be praised, God showed me the way; in that valley of the Ngarai I said: Yes, Independent Indonesia can only be achieved with Dai Nippon...For the first time in all my life, I saw myself in the mirror of Asia." In July 1942, Sukarno was sent back to

Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

, where he re-united with other nationalist leaders recently released by the Japanese, including

Mohammad Hatta. There, he met the Japanese commander General

Hitoshi Imamura, who asked Sukarno and other nationalists to galvanise support from Indonesian populace to aid the Japanese war effort.

Sukarno was willing to support the Japanese, in exchange for a platform for himself to spread nationalist ideas to the mass population.

The Japanese, on the other hand, needed Indonesia's workforce and natural resources to help its war effort. The Japanese recruited millions of people, mainly from

Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mo ...

, to be forced labour called "

romusha" in

Japanese. They were forced to build railways, airfields, and other facilities for the Japanese within Indonesia and as far away as Burma. Additionally, the Japanese requisitioned rice and other food produced by Indonesian peasants to supply their troops, while forcing the peasantry to cultivate

castor oil plants to be used as aviation fuel and lubricants.

To gain cooperation from Indonesian population and to prevent resistance to these measures, the Japanese put Sukarno as head of ''Tiga-A'' mass organisation movement. In March 1943, the Japanese formed a new organisation called ''Poesat Tenaga Rakjat'' (POETERA/ Center of People's Power) under Sukarno, Hatta,

Ki Hadjar Dewantara, and

KH Mas Mansjoer. These organisations aimed to galvanise popular support for recruitment of ''romusha'', to requisition of food products, and to promote pro-Japanese and

anti-Western sentiments amongst Indonesians. Sukarno coined the term, ''Amerika kita setrika, Inggris kita linggis'' ("Let's iron America, and bludgeon the British") to promote anti-Allied sentiments. In later years, Sukarno was lastingly ashamed of his role with the ''romusha''. Additionally, food requisitioning by the Japanese caused widespread famine in Java, which killed more than one million people in 1944–1945. In his view, these were necessary sacrifices to be made to allow for the future independence of Indonesia.

He also was involved with the formation of ''

Defenders of the Homeland

''Pembela Tanah Air'' (abbreviated PETA; ) or was an Indonesian volunteer army established on 3 October 1943 in Indonesia by the occupying Japanese. The Japanese intended PETA to assist their forces in opposing a possible invasion by the Allies ...

'' (PETA) and ''

Heiho

were native Indonesian units raised by the Imperial Japanese Army during its occupation of the Dutch East Indies in World War II. Alongside the ''Heiho'', the Japanese organized ''Giyūgun'' (義勇軍, "Volunteer army"), such as the Java-based ...

'' (Indonesian volunteer army troops) via speeches broadcast on the Japanese radio and loudspeaker networks across Java and Sumatra. By mid-1945 these units numbered around two million and were preparing to defeat any Allied forces sent to re-take Java.

In the meantime, Sukarno eventually divorced Inggit, who refused to accept her husband's wish for polygamy. She was provided with a house in

Bandung

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

and a pension for the rest of her life. In 1943, he married

Fatmawati. They lived in a house in Jalan Pegangsaan Timur No. 56, confiscated from its previous Dutch owners and presented to Sukarno by the Japanese. This house would later be the venue of the

Proclamation of Indonesian Independence in 1945.

On 10 November 1943, Sukarno and Hatta were sent on a 17-day tour of Japan, where they were decorated by Emperor

Hirohito and wined and dined in the house of Prime Minister

Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

in

Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

. On 7 September 1944, with the war going badly for the Japanese,

Prime Minister Kuniaki Koiso promised independence for Indonesia, although no date was set.

[Ricklefs (1991), page 207] This announcement was seen, according to the U.S. official history, as immense vindication for Sukarno's apparent collaboration with the Japanese.

The U.S. at the time considered Sukarno one of the "foremost collaborationist leaders."

Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence

On 29 April 1945, when

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

liberated by American forces, the Japanese allowed for the establishment of the

Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (BPUPK), a quasi-legislature consisting of 67 representatives from most ethnic groups in Indonesia. Sukarno was appointed as head of the BPUPK and was tasked to lead discussions to prepare the basis of a future Indonesian state. To provide a common and acceptable platform to unite the various squabbling factions in the BPUPK, Sukarno formulated his ideological thinking developed over the previous twenty years into five principles. On 1 June 1945, he introduced these five principles, known as ''

pancasila'', during the joint session of the BPUPK held in the former

Volksraad The Volksraad was a people's assembly or legislature in Dutch or Afrikaans speaking government.

Assembly South Africa

* Volksraad (South African Republic) (1840–1902)

* Volksraad (Natalia Republic), a similar assembly that existed in the Natalia ...

Building (now called the

Pancasila Building

The Pancasila Building () is a historic building located in Central Jakarta, Indonesia. The name "Pancasila" refers to the speech delivered by Sukarno in the building on which he spoke about the concept of Pancasila, a philosophical concept whic ...

).

''Pancasila'', as presented by Sukarno during the BPUPK speech, consisted of five principles which Sukarno saw as commonly shared by all Indonesians:

# Nationalism, whereby a united Indonesian state would stretch from

Sabang to

Merauke

Merauke is a large town and the capital of the South Papua province, Indonesia. It is also the administrative centre of Merauke Regency in South Papua. It is considered the easternmost city in Indonesia. The town was originally called Ermasoe. I ...

, encompassing all former

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

# Internationalism, meaning Indonesia is to appreciate human rights and contribute to world peace, and should not fall into chauvinistic fascism such as displayed by

Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

with their belief in the racial superiority of

Aryans

# Democracy, which Sukarno believed has always been in the blood of Indonesians through the practice of consensus-seeking (''musyawarah untuk muafakat''), an Indonesian-style democracy different from Western-style liberalism

# Social justice, a form of populist socialism in economics with Marxist-style opposition to free capitalism. Social justice also intended to provide an equal share of the economy to all Indonesians, as opposed to the complete economic domination by the Dutch and Chinese during the colonial period

# Belief in God, whereby all religions are treated equally and have religious freedom. Sukarno saw Indonesians as spiritual and religious people, but in essence tolerant towards different religious beliefs

On 22 June, the Islamic and nationalist elements of the BPUPK created a small committee of nine, which formulated Sukarno's ideas into the five-point

Pancasila, in a document known as the

Jakarta Charter

The Jakarta Charter ( id, Piagam Jakarta) was a document drawn up by members of the Indonesian Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (BPUPK) on 22 June 1945 in Jakarta that later formed the basis of the preamble to the Con ...

:

# Belief in one and only Almighty God with obligation for Muslims to adhere to Islamic law

# Civilised and just humanity

# Unity of Indonesia

# Democracy through inner wisdom and representative consensus-building

# Social justice for all Indonesians

Due to pressure from the Islamic element, the first principle mentioned the obligation for Muslims to practice Islamic law (

sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

). However, the final Sila as contained in the 1945 Constitution which was put into effect on 18 August 1945, excluded the reference to Islamic law for the sake of national unity. The elimination of

sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

was done by

Mohammad Hatta based upon a request by Christian representative

Alexander Andries Maramis, and after consultation with moderate Islamic representatives Teuku Mohammad Hassan, Kasman Singodimedjo, and Ki Bagoes Hadikoesoemo.

Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence

On 7 August 1945, the Japanese allowed the formation of a smaller

Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence

The Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence ( id, Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia), PPKI, ja, 独立準備委員会, Dokuritsu Junbi Iinkai, lead=yes) was a body established on 7 August 1945 to prepare for the transfer of auth ...

(PPKI), a 21-person committee tasked with creating the specific governmental structure of the future Indonesian state. On 9 August, the top leaders of PPKI (Sukarno, Hatta, and

KRT Radjiman Wediodiningrat), were summoned by Commander-in-Chief of Japan's Southern Expeditionary Forces, Field Marshal

Hisaichi Terauchi, to

Da Lat

Da Lat (also written as Dalat, vi, Đà Lạt; ), is the capital of Lâm Đồng Province and the largest city of the Central Highlands region in Vietnam. The city is located above sea level on the Langbian Plateau. Da Lat is one of the mo ...

, 100 km from

Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

. Field Marshal Terauchi gave Sukarno the freedom to proceed with preparation for Indonesian independence, free of Japanese interference. After much wining and dining, Sukarno's entourage was flown back to Jakarta on 14 August. Unbeknownst to the guests,

atomic bombs had been dropped on

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui ...

and

Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, and the Japanese were preparing for

surrender.

Japanese surrender

The following day, on 15 August, the Japanese declared their acceptance of the

Potsdam Declaration terms and unconditionally surrendered to the Allies. On the afternoon of that day, Sukarno received this information from leaders of youth groups and members of PETA

Chairul Saleh

Chairul Saleh Dt Paduko Rajo (September 13, 1916 – February 8, 1967) was born in Sawahlunto, West Sumatra. He was an Indonesian government minister and vice prime minister during the Sukarno presidency. He was a close confidant of Sukarno, whom ...

,

Soekarni, and

Wikana, who had been listening to Western radio broadcasts. They urged Sukarno to declare Indonesian independence immediately, while the Japanese were in confusion and before the arrival of Allied forces. Faced with this quick turn of events, Sukarno procrastinated. He feared bloodbath due to hostile response from the Japanese to such a move and was concerned with prospects of future Allied retribution.

Kidnapping

At early morning on 16 August, the three youth leaders, impatient with Sukarno's indecision, kidnapped him from his house and brought him to a small house in Rengasdengklok,

Karawang, owned by a Chinese family and occupied by PETA. There they gained Sukarno's commitment to declare independence the next day. That night, the youths drove Sukarno back to the house of Admiral Tadashi Maeda, the Japanese naval liaison officer in the

Menteng area of Jakarta, who sympathised with Indonesian independence. There, he and his assistant Sajoeti Melik prepared the text of the

Proclamation of Indonesian Independence.

Indonesian National Revolution

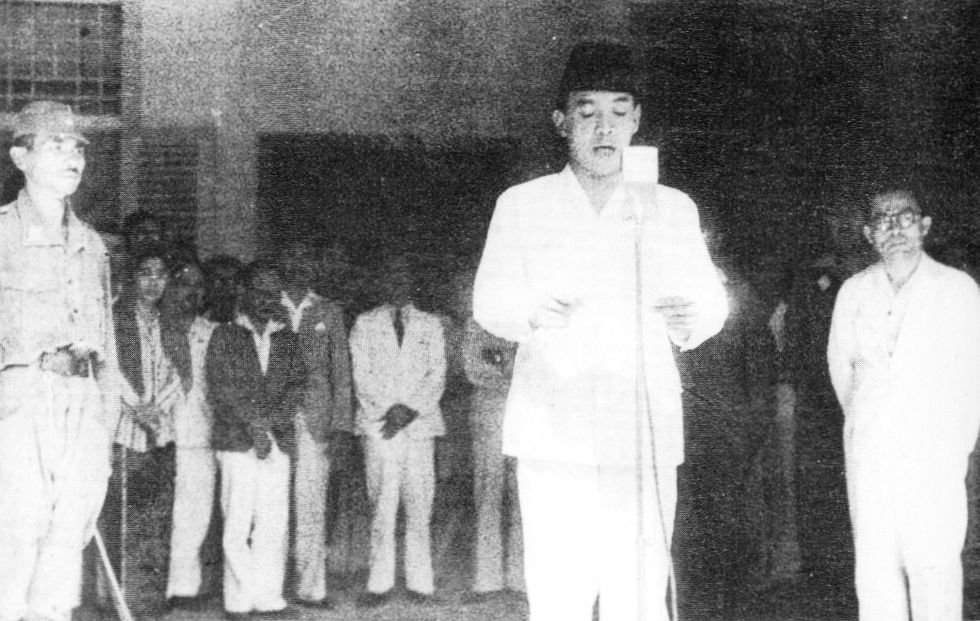

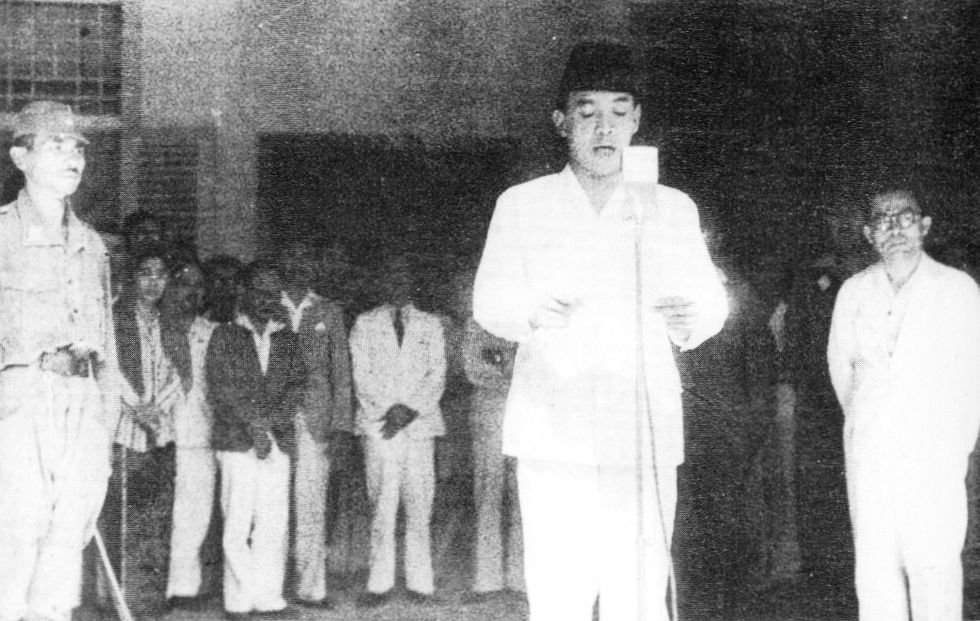

Proclamation of Indonesian Independence

In the early morning of 17 August 1945, Sukarno returned to his house at Jalan Pegangsaan Timur No. 56, where

Mohammad Hatta joined him. Throughout the morning, impromptu leaflets printed by PETA and youth elements informed the population of the impending proclamation. Finally, at 10 am, Sukarno and Hatta stepped to the front porch, where Sukarno declared the

independence of the Republic of Indonesia in front of a crowd of 500 people. This most historic of buildings was later ordered to be demolished by Sukarno himself, without any apparent reason.

On the following day, 18 August, the PPKI declared the basic governmental structure of the new Republic of Indonesia:

# Appointing Sukarno and

Mohammad Hatta as president and vice-president and their cabinet.

# Putting into effect the 1945 Indonesian

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

, which by this time excluded any reference to Islamic law.

# Establishing a

Central Indonesian National Committee (''Komite Nasional Indonesia Poesat''/KNIP) to assist the president before an election of a parliament.

Sukarno's vision for the 1945 Indonesian

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

comprised the

Pancasila (''five principles''). Sukarno's political philosophy was mainly a fusion of elements of

Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

,

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

and

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

. This is reflected in a proposition of his version of Pancasila he proposed to the

Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (BPUPK) in a speech on 1 June 1945.

Sukarno argued that all of the principles of the nation could be summarised in the phrase ''

gotong royong.'' The Indonesian parliament, founded on the basis of this original (and subsequently revised) constitution, proved all but ungovernable. This was due to irreconcilable differences between various social, political, religious and ethnic factions.

Revolution and Bersiap

In the days following the proclamation, the news of Indonesian independence was spread by radio, newspaper, leaflets, and word of mouth despite attempts by the Japanese soldiers to suppress the news. On 19 September, Sukarno addressed a crowd of one million people at the Ikada Field of Jakarta (now part of

Merdeka Square) to commemorate one month of independence, indicating the strong level of popular support for the new Republic, at least on Java and Sumatra. In these two islands, the Sukarno government quickly established governmental control while the remaining Japanese mostly retreated to their barracks awaiting the arrival of Allied forces. This period was marked by constant attacks by armed groups on Europeans, Chinese, Christians, native aristocracy and anyone who were perceived to oppose Indonesian independence. The most serious cases were the Social Revolutions in

Aceh

Aceh ( ), officially the Aceh Province ( ace, Nanggroë Acèh; id, Provinsi Aceh) is the westernmost province of Indonesia. It is located on the northernmost of Sumatra island, with Banda Aceh being its capital and largest city. Granted a ...

and

North Sumatra, where large numbers of Acehnese and Malay aristocrats were killed by Islamic groups (in Aceh) and communist-led mobs (in North Sumatra), and the "Three Regions Affair" in northwestern coast of

Central Java

Central Java ( id, Jawa Tengah) is a province of Indonesia, located in the middle of the island of Java. Its administrative capital is Semarang. It is bordered by West Java in the west, the Indian Ocean and the Special Region of Yogyakart ...

where large numbers of Europeans, Chinese, and native aristocrats were butchered by mobs. These bloody incidents continued until late 1945 to early 1946, and begin to peter out as Republican authorities begin to exert and consolidate control.

Sukarno's government initially postponed the formation of a national army, for fear of antagonizing the Allied occupation forces and their doubt over whether they would have been able to form an adequate military apparatus to maintain control of seized territory. The members of various

militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

groups formed during Japanese occupation such as the disbanded PETA and ''Heiho'', at that time were encouraged to join the BKR—''Badan Keamanan Rakjat'' (The People's Security Organization)—itself a subordinate of the "War Victims Assistance Organization". It was only in October 1945 that the BKR was reformed into the TKR—''Tentara Keamanan Rakjat'' (The People's Security Army) in response to the increasing Allied and Dutch presence in Indonesia. The TKR armed themselves mostly by attacking Japanese troops and confiscating their weapons.

Due to the sudden transfer of Java and Sumatra from General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

's American-controlled Southwest Pacific Command to

Lord Louis Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

's British-controlled Southeast Asian Command, the first Allied soldiers (1st Battalion of Seaforth Highlanders) did not arrive in Jakarta until late September 1945. British forces began to occupy major Indonesian cities in October 1945. The commander of the British 23rd Division, Lieutenant General Sir

Philip Christison

General Sir Alexander Frank Philip Christison, 4th Baronet, (17 November 1893 – 21 December 1993) was a British Army officer who served with distinction during the world wars. After service as a junior officer on the Western Front in the Fir ...

, set up command in the former governor-general's palace in Jakarta. Christison stated that he intended to free all Allied prisoners-of-war and to allow the return of Indonesia to its pre-war status, as a colony of Netherlands. The Republican government were willing to cooperate with the release and repatriation of Allied civilians and military POWs, setting-up the Committee for the Repatriation of Japanese and Allied Prisoners of Wars and Internees (''Panitia Oeroesan Pengangkoetan Djepang dan APWI''/POPDA) for this purpose. POPDA, in cooperation with the British, repatriated more than 70,000 Japanese and Allied POWs and internees by the end of 1946. However, due to the relative weakness of the military of the Republic of Indonesia, Sukarno sought independence by gaining international recognition for his new country rather than engage in battle with British and Dutch military forces.

Sukarno was aware that his history as a Japanese

collaborator and his leadership in the Japanese-approved

PUTERA during the occupation would make the Western countries distrustful of him. To help gain international recognition as well as to accommodate domestic demands for representation, Sukarno "allowed" the formation of a parliamentary system of government, whereby a

prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

controlled day-to-day affairs of the government, while Sukarno as president remained as a figurehead. The prime minister and his cabinet would be responsible to the

Central Indonesian National Committee instead of the president. On 14 November 1945, Sukarno appointed

Sutan Sjahrir

Sutan Sjahrir (5 March 1909 – 9 April 1966) was an Indonesian politician, and revolutionary independence leader, who served as the first Prime Minister of Indonesia, from 1945 until 1947. Previously, he was a key Indonesian nationalist organiz ...

as first prime minister; he was a European-educated politician who was never involved with the Japanese occupation authorities.

In late 1945 Dutch administrators who led the Dutch East Indies government-in-exile and soldiers who had fought the Japanese began to return under the name of Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA), with the protection of the British. They were led by

Hubertus Johannes van Mook, a colonial administrator who had evacuated to

Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

, Australia. Dutch soldiers who had been POWs under the Japanese were released and rearmed. Shooting between these Dutch soldiers and police supporting the new Republican government Indonesian and civilians soon developed. This soon escalated to armed conflict between the newly constituted Republican forces aided by a myriad of pro-independence mobs and the Dutch and British forces. On 10 November, a full-scale

battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and for ...

broke out in

Surabaya

Surabaya ( jv, ꦱꦸꦫꦧꦪ or jv, ꦯꦹꦫꦨꦪ; ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of East Java and the second-largest city in Indonesia, after Jakarta. Located on the northeastern border of Java island, on the M ...

between the 49th Infantry Brigade of the

British Indian Army

The British Indian Army, commonly referred to as the Indian Army, was the main military of the British Raj before its dissolution in 1947. It was responsible for the defence of the British Indian Empire, including the princely states, which cou ...

and Indonesian nationalist militias. The British-Indian force were supported by air and naval forces. Some 300 Indian soldiers were killed (including their commander Brigadier

Aubertin Walter Sothern Mallaby

Brigadier Aubertin Walter Sothern Mallaby CIE OBE (12 December 1899 – 30 October 1945) was a British Indian Army officer killed in a shootout during the Battle of Surabaya in what was then the newly proclaimed as independent Republic of Indon ...

), as were thousands of nationalist militiamen and other Indonesians. Shootouts broke out with alarming regularity in

Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

, including an attempted assassination of Prime Minister

Sjahrir by Dutch gunmen. To avoid this menace, Sukarno and majority of his government left for the safety of

Yogyakarta on 4 January 1946. There, the Republican government received protection and full support from Sultan

Hamengkubuwono IX

Hamengkubuwono IX or HB IX (12 April 1912 – 2 October 1988) was an Indonesian statesman and royal who was the second vice president of Indonesia, the ninth sultan of Yogyakarta, and the first governor of the Special Region of Yogyakarta. Hamen ...

. Yogyakarta would remain as the Republic's capital until the end of the war in 1949.

Sjahrir remained in Jakarta to conduct negotiations with the British.

The initial series of battles in late 1945 and early 1946 left the British in control of major port cities on Java and Sumatra. During the Japanese occupation, the Outer Islands (excluding Java and Sumatra) were occupied by the Japanese Navy (

Kaigun), who did not allow for political mobilisation of the islanders. Consequently, there was little Republican activity in these islands post-proclamation. Australian and Dutch forces were able to quickly take control of these islands without much fighting by the end of 1945 (excluding the resistance of

I Gusti Ngurah Rai in Bali, the insurgency in

South Sulawesi, and fighting in Hulu Sungai area of

South Kalimantan). Meanwhile, the hinterland areas of Java and Sumatra remained under Republican control.

Eager to pull its soldiers out of Indonesia, the British allowed for large-scale infusion of Dutch forces into the country throughout 1946. By November 1946, all British soldiers had been withdrawn from Indonesia. They were replaced with more than 150,000 Dutch soldiers. The British sent Lord

Archibald Clark Kerr, 1st Baron Inverchapel

Archibald Clark Kerr, 1st Baron Inverchapel, (17 March 1882 – 5 July 1951), known as Sir Archibald Clark Kerr between 1935 and 1946, was a British diplomat. He served as Ambassador to the Soviet Union between 1942 and 1946 and to the United ...

and

Miles Lampson, 1st Baron Killearn to bring the Dutch and Indonesians to the negotiating table. The result of these negotiations was the

Linggadjati Agreement

The Linggardjati Agreement (''Linggarjati'' in modern Indonesian spelling) was a political accord concluded on 15 November 1946 by the Dutch administration and the unilaterally declared Republic of Indonesia in the village of Linggarjati, Kuning ...

signed in November 1946, where the Dutch acknowledged ''

de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

'' Republican sovereignty over Java, Sumatra, and Madura. In exchange, the Republicans were willing to discuss a future Commonwealth-like United Kingdom of Netherlands and Indonesia.

Linggadjati Agreement and Operation Product

Linggadjati Agreement

Sukarno's decision to negotiate with the Dutch was met with strong opposition by various Indonesian factions.

Tan Malaka, a

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

politician, organised these groups into a united front called the ''Persatoean Perdjoangan'' (PP). PP offered a "Minimum Program" which called for complete independence, nationalisation of all foreign properties, and rejection of all negotiations until all foreign troops are withdrawn. These programmes received widespread popular support, including from armed forces commander General

Sudirman. On 4 July 1946, military units linked with PP kidnapped Prime Minister

Sjahrir who was visiting

Yogyakarta. Sjahrir was leading the negotiation with the Dutch. Sukarno, after successfully influencing

Sudirman, managed to secure the release of Sjahrir and the arrest of

Tan Malaka and other PP leaders. Disapproval of Linggadjati terms within the

KNIP led Sukarno to issue a decree doubling KNIP membership by including many pro-agreement appointed members. As a consequence, KNIP ratified the

Linggadjati Agreement

The Linggardjati Agreement (''Linggarjati'' in modern Indonesian spelling) was a political accord concluded on 15 November 1946 by the Dutch administration and the unilaterally declared Republic of Indonesia in the village of Linggarjati, Kuning ...

in March 1947.

Operation Product

On 21 July 1947, the

Linggadjati Agreement

The Linggardjati Agreement (''Linggarjati'' in modern Indonesian spelling) was a political accord concluded on 15 November 1946 by the Dutch administration and the unilaterally declared Republic of Indonesia in the village of Linggarjati, Kuning ...

was broken by the Dutch, who launched

Operatie Product

Operation Product was a Dutch military offensive against areas of Java and Sumatra controlled by the Republic of Indonesia during the Indonesian National Revolution.Vickers (2005), p. 99 It took place between 21 July and 4 August 1947. Referr ...

, a massive military invasion into Republican-held territories. Although the newly reconstituted

TNI was unable to offer significant military resistance, the blatant violation by the Dutch of an internationally brokered agreement outraged world opinion. International pressure forced the Dutch to halt their invasion force in August 1947. Sjahrir, who has been replaced as prime minister by

Amir Sjarifuddin

Amir Sjarifuddin Harahap (EVO: Amir Sjarifoeddin Harahap; 27 April 1907 – 19 December 1948) was an Indonesian politician and journalist who served as the second prime minister of Indonesia from 1947 until 1948. A major leader of the lef ...

, flew to

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

to appeal Indonesian case in front of

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

. UN Security Council issued a resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire and appointed a Good Offices Committee (GOC) to oversee the ceasefire. The GOC, based in Jakarta, consisted of delegations from Australia (led by

Richard Kirby, chosen by Indonesia), Belgium (led by

Paul van Zeeland, chosen by the Netherlands), and United States (led by

Frank Porter Graham

Frank Porter Graham (October 14, 1886 – February 16, 1972) was an American educator and political activist. A professor of history, he was elected President of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1930, and he later became the firs ...

, neutral).

The Republic was now under firm Dutch military stranglehold, with the Dutch military occupying

West Java, and the northern coast of

Central Java

Central Java ( id, Jawa Tengah) is a province of Indonesia, located in the middle of the island of Java. Its administrative capital is Semarang. It is bordered by West Java in the west, the Indian Ocean and the Special Region of Yogyakart ...

and

East Java

East Java ( id, Jawa Timur) is a province of Indonesia located in the easternmost hemisphere of Java island. It has a land border only with the province of Central Java to the west; the Java Sea and the Indian Ocean border its northern and ...

, along with the key productive areas of

Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

. Additionally, the Dutch navy blockaded Republican areas from supplies of vital food, medicine, and weapons. As a consequence, Prime Minister

Amir Sjarifuddin

Amir Sjarifuddin Harahap (EVO: Amir Sjarifoeddin Harahap; 27 April 1907 – 19 December 1948) was an Indonesian politician and journalist who served as the second prime minister of Indonesia from 1947 until 1948. A major leader of the lef ...

had little choice but to sign the

Renville Agreement

The Renville Agreement was a United Nations Security Council-brokered political accord between the Netherlands, which was seeking to re-establish its colony in South East Asia, and Indonesian Republicans seeking for Indonesian independence dur ...

on 17 January 1948, which acknowledged Dutch control over areas taken during

Operatie Product

Operation Product was a Dutch military offensive against areas of Java and Sumatra controlled by the Republic of Indonesia during the Indonesian National Revolution.Vickers (2005), p. 99 It took place between 21 July and 4 August 1947. Referr ...

, while the Republicans pledged to withdraw all forces that remained on the other side of the ceasefire line ("Van Mook Line"). Meanwhile, the Dutch begin to organise

puppet states

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

in the areas under their occupation, to counter Republican influence utilising ethnic diversity of Indonesia.

Renville agreement and Madiun affair

The signing of highly disadvantageous Renville Agreement caused even greater instability within the Republican political structure. In Dutch-occupied West Java,

Darul Islam guerrillas under

Sekarmadji Maridjan Kartosuwirjo maintained their anti-Dutch resistance and repealed any loyalty to the Republic; they caused a bloody insurgency in West Java and other areas in the first decades of independence. Prime Minister

Sjarifuddin, who signed the agreement, was forced to resign in January 1948 and was replaced by

Mohammad Hatta. Hatta cabinet's policy of rationalising the armed forces by demobilising large numbers of armed groups that proliferated the Republican areas also caused severe disaffection. Leftist political elements, led by resurgent

Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) under

Musso took advantage of public disaffections by launching a rebellion in

Madiun,

East Java

East Java ( id, Jawa Timur) is a province of Indonesia located in the easternmost hemisphere of Java island. It has a land border only with the province of Central Java to the west; the Java Sea and the Indian Ocean border its northern and ...

, on 18 September 1948. Bloody fighting continued during late-September until end of October 1948, when the last communist bands were defeated, and Musso shot dead. The communists had overestimated their potential to oppose the strong appeal of Sukarno amongst the population.

Operatie Kraai and exile

Invasion and exile

On 19 December 1948, to take advantage of the Republic's weak position following the communist rebellion, the Dutch launched

Operatie Kraai

Operation Kraai (Operation Crow) was a Dutch military offensive against the '' de facto'' Republic of Indonesia in December 1948 after negotiations failed. With the advantage of surprise the Dutch managed to capture the Indonesian Republic's ...

, a second military invasion designed to crush the Republic once and for all. The invasion was initiated with an airborne assault on Republican capital

Yogyakarta. Sukarno ordered the armed forces under

Sudirman to launch a guerrilla campaign in the countryside, while he and other key leaders such as Hatta and

Sjahrir allowed themselves to be taken prisoner by the Dutch. To ensure continuity of government, Sukarno sent a telegram to

Sjafruddin Prawiranegara, providing him with the mandate to lead an Emergency Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PDRI), based on the unoccupied hinterlands of

West Sumatra

West Sumatra ( id, Sumatra Barat) is a province of Indonesia. It is located on the west coast of the island of Sumatra and includes the Mentawai Islands off that coast. The province has an area of , with a population of 5,534,472 at the 2020 cen ...

, a position he kept until Sukarno was released in June 1949. The Dutch sent Sukarno and other captured Republican leaders to captivity in Parapat, in Dutch-occupied part of

North Sumatra and later to the island of

Bangka.

Aftermath

The second Dutch invasion caused even more international outrage. The United States, impressed by Indonesia's ability to defeat the 1948 communist challenge without outside help, threatened to cut off

Marshall Aid funds to the Netherlands if military operations in Indonesia continued. TNI did not disintegrate and continued to wage guerrilla resistance against the Dutch, most notably the assault on Dutch-held Yogyakarta led by

Lieutenant-Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colo ...

Suharto on 1 March 1949. Consequently, the Dutch were forced to sign the

Roem–Van Roijen Agreement on 7 May 1949. According to this treaty, the Dutch released the Republican leadership and returned the area surrounding

Yogyakarta to Republican control in June 1949. This was followed by the

Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference held in

The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

which led to the complete transfer of

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

by the Queen

Juliana of the Netherlands

Juliana (; Juliana Louise Emma Marie Wilhelmina; 30 April 1909 – 20 March 2004) was Queen of the Netherlands from 1948 until her abdication in 1980.

Juliana was the only child of Queen Wilhelmina and Prince Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. ...

to Indonesia, on 27 December 1949. On that day, Sukarno flew from Yogyakarta to

Jakarta

Jakarta (; , bew, Jakarte), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta ( id, Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta) is the capital city, capital and list of Indonesian cities by population, largest city of Indonesia. Lying on the northwest coa ...

, making a triumphant speech at the steps of the governor-general's palace, immediately renamed the

Merdeka Palace ("Independence Palace").

President of the United States of Indonesia

At this time, as part of a compromise with the Dutch, Indonesia adopted a new

federal constitution that made the country a federal state called the Republic of

United States of Indonesia

The United States of Indonesia ( nl, Verenigde Staten van Indonesië, id, Republik Indonesia Serikat, abbreviated as RIS), was a short-lived federal state to which the Netherlands formally transferred sovereignty of the Dutch East Indies (exce ...

(

Indonesian: ''Republik Indonesia Serikat, RIS''), consisting of the Republic of Indonesia whose borders were determined by the "Van Mook Line", along with the six states and nine autonomous territories created by the Dutch. During the first half of 1950, these states gradually dissolved themselves as the Dutch military that previously propped them up was withdrawn. In August 1950, with the last state – the

State of East Indonesia

The State of East Indonesia ( id, Negara Indonesia Timur, old spelling: ''Negara Indonesia Timoer'', nl, Oost-Indonesië) was a post– World War II state formed in the eastern half of Dutch East Indies. Established in December 1946, it becam ...

– dissolving itself, Sukarno declared a Unitary Republic of Indonesia based on the newly formulated

provisional constitution of 1950.

Liberal democracy period (1950–1959)

Both the Federal Constitution of 1949 and the Provisional Constitution of 1950 were parliamentary in nature, where executive authority laid with the prime minister, and which—on paper—limited presidential power. However, even with his formally reduced role, he commanded a good deal of

moral authority Moral authority is authority premised on principles, or fundamental truths, which are independent of written, or positive, laws. As such, moral authority necessitates the existence of and adherence to truth. Because truth does not change, the princi ...

as

Father of the Nation.

Instability

The first years of parliamentary democracy proved to be very unstable for Indonesia. Cabinets fell in rapid succession due to the sharp differences between the various political parties within the

newly appointed parliament (''Dewan Perwakilan Rakjat''/DPR). There were severe disagreements on future path of Indonesian state, between nationalists who wanted a

Secular state

A secular state is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regard ...

(led by

Partai Nasional Indonesia first established by Sukarno), the Islamists who wanted an

Islamic state

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic ter ...

(led by

Masyumi Party), and the communists who wanted a

Communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

(led by

PKI, only allowed to operate again in 1951). On the economic front, there was severe dissatisfaction with continuing economic domination by large Dutch corporations and the ethnic-Chinese.

Darul Islam rebels

The

Darul Islam rebels under

Kartosuwirjo in West Java refused to acknowledge Sukarno's authority and declared an NII (Negara Islam Indonesia – Islamic State of Indonesia) in August 1949. Rebellions in support of Darul Islam also broke out in

South Sulawesi in 1951, and in

Aceh

Aceh ( ), officially the Aceh Province ( ace, Nanggroë Acèh; id, Provinsi Aceh) is the westernmost province of Indonesia. It is located on the northernmost of Sumatra island, with Banda Aceh being its capital and largest city. Granted a ...

in 1953. Meanwhile, pro-federalism members of the disbanded

KNIL launched failed rebellion in

Bandung

Bandung ( su, ᮘᮔ᮪ᮓᮥᮀ, Bandung, ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of West Java. It has a population of 2,452,943 within its city limits according to the official estimates as at mid 2021, making it the fourth most ...

(

APRA rebellion of 1950), in

Makassar in 1950, and Ambon (

Republic of South Maluku revolt of 1950).

Division in the Military

Additionally, the military was torn by hostilities between officers originating from the colonial-era