Storer College on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Storer College was a

Storer College was a

Storer College was a

Storer College was a historically Black college

Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of serving African Americans. Most are in the Southern U ...

in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 269 at the 2020 United States census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah Rivers in the ...

, that operated from 1867 to 1955. A national icon for Black Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

, in the town where the 'end of American slavery began', as Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

famously put it, it was a unique institution whose focus changed several times. There is no one category of college into which it fits neatly. Sometimes white students studied alongside Black students, which at the time was prohibited by law at state-regulated schools in West Virginia and the other Southern states.

In the early twentieth century, Storer was at the center of the growing protest movement against Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

treatment that would lead to the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

and the Civil Rights Movement. The first American meeting of the predecessor of the NAACP, the Niagara Movement

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. The Ni ...

, was held at Storer in 1906.

John Brown's Fort, a symbol of the end of slavery in the United States

From the late 18th century to the 1860s, various states of the United States allowed the enslavement of human beings, most of whom had been transported from Africa during the Atlantic slave trade or were their descendants. The institution of ch ...

, was located from 1909 until 1968 on the Storer campus, where it was once used as the college museum (the "fort" has since been moved back to the lower town). Although the college closed in 1955, much of the Storer campus is now preserved as part of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, originally Harpers Ferry National Monument, is located at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah rivers in and around Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The park includes ...

.

Location

"The locality is eminently healthful, and one of the most beautiful that can be imagined." According to an article in the ''Journal of Negro Education

''The Journal of Negro Education'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal published by Howard University, established in 1932 by Charles Henry Thompson, who was its editor-in-chief for more than 30 years.Free Baptists and the

Residents of Harpers Ferry tried everything from

Residents of Harpers Ferry tried everything from

The

The

Over the first forty years of the college, enrollment averaged 176. However,

it varied dramatically with the season. For example, in 1873–74, there were 80 fall term students, 167 in the winter term, and for the summer, 124.

The first 8 graduates of the Storer Normal School graduated in 1872. In 1874, a writer observed that the demand for these "colored teachers...is far beyond the capacity of the college with its present means and endowments to supply." By 1877 there were 100 former students teaching, of which 37 were graduates, and many of the remainder returned termittently to complete their education. That year a semi-annual, week-long teachers' institute was inaugurated.

The first graduates of the Academic Department were in 1880.

In 1871 there were 203 enrollees. Counting those still students, Academic Department, 42 students; Normal Department, 174 students; Preparatory Division, 101 students. As of that date there had been 285 different students enrolled. The same year, the '' Spirit of Jefferson'' newspaper reported "more than 150...of all ages and sexes, and...all shades and colors." In 1875, there were 285.

In 1881, a report of the Free-Will Baptists indicates that at Storer there were 200 enrolled students, 62 graduates, level unspecified, and the total number who had enrolled at some time was 800. The report also says that the College had "sent out" over 200 teachers and 25 preachers. In 1882–84 there were 63 enrolled in the three-year normal school training.

In its first 20 years, the school trained hundreds of teachers from West Virginia, Ohio, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

In 1895 there were 250 graduates of the Normal Department.

In 1901 there were 49 male and 73 female students.

In 1931 there were 130 students, 52 at the junior college level and 78 at the high school level.

Over its 90-year history, about 7,000 students enrolled. The Storer College Alumni Association has a 70-page list on its web site. As of the later 19th century students came from 14 states and 4 foreign countries.

Over the first forty years of the college, enrollment averaged 176. However,

it varied dramatically with the season. For example, in 1873–74, there were 80 fall term students, 167 in the winter term, and for the summer, 124.

The first 8 graduates of the Storer Normal School graduated in 1872. In 1874, a writer observed that the demand for these "colored teachers...is far beyond the capacity of the college with its present means and endowments to supply." By 1877 there were 100 former students teaching, of which 37 were graduates, and many of the remainder returned termittently to complete their education. That year a semi-annual, week-long teachers' institute was inaugurated.

The first graduates of the Academic Department were in 1880.

In 1871 there were 203 enrollees. Counting those still students, Academic Department, 42 students; Normal Department, 174 students; Preparatory Division, 101 students. As of that date there had been 285 different students enrolled. The same year, the '' Spirit of Jefferson'' newspaper reported "more than 150...of all ages and sexes, and...all shades and colors." In 1875, there were 285.

In 1881, a report of the Free-Will Baptists indicates that at Storer there were 200 enrolled students, 62 graduates, level unspecified, and the total number who had enrolled at some time was 800. The report also says that the College had "sent out" over 200 teachers and 25 preachers. In 1882–84 there were 63 enrolled in the three-year normal school training.

In its first 20 years, the school trained hundreds of teachers from West Virginia, Ohio, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

In 1895 there were 250 graduates of the Normal Department.

In 1901 there were 49 male and 73 female students.

In 1931 there were 130 students, 52 at the junior college level and 78 at the high school level.

Over its 90-year history, about 7,000 students enrolled. The Storer College Alumni Association has a 70-page list on its web site. As of the later 19th century students came from 14 states and 4 foreign countries.

L. Douglas Wilder Library and Learning Resource Center

holds Storer College's former library collection and some of the college's records. Other Storer College records are held at the library of

Freedmen's Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was a U.S. government agency of early post American Civil War Reconstruction, assisting freedmen (i.e., former enslaved people) in the ...

. Its first class was 19 formerly enslaved children, described as "poorly clad, ill-kept, and undisciplined", who desperately needed the basic skills of reading, writing, and arithmetic.

At a conference in 2015 honoring the 150th anniversary of Storer College, John Cuthbert, head of the West Virginia & Regional History Center, observed:

Once slavery was ended in the United States and the education of blacks was no longer prohibited, there was a "wild rush for the schools".

A $10,000 matching grant from John Storer, a philanthropist from Maine, led to the charter of "a school which might eventually become a College, to be in located in one of the Southern States, at which youth could be educated without distinction of race or color". Though called a college from the beginning, it was a normal school until into the twentieth century, providing high school-level instruction to future primary school teachers. It also is not " historically black" in the usual sense. The student body was overwhelmingly black, and in the 1910 advertisement reproduced at right it describes itself as "for Colored students", but there were some white students. It was also ahead of its time in that it accepted both male and female students, which then was unusual.

The Free Baptists called Storer their greatest success. The U.S. Congress turned over to it four buildings that had been used for housing at the former Harpers Ferry National Armory. The school gradually expanded its offerings, adding a traditional or "collegiate" high school, an industrial division, then junior college classes, and finally four-year programs. The College built additional buildings. Until 1891, when the state West Virginia Colored Institute opened, it was the only college in West Virginia that accepted non-white students.

The choice of Harpers Ferry

In 1865, as a representative ofNew England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

's Freewill Baptist Home Mission Society, charged with coordinating their instructional efforts in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The Valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the east ...

and surrounding areas, Reverend Nathan Cook Brackett chose centrally-located Harpers Ferry as his base. The Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, on low ground adjoining the rail line and the Potomac, was destroyed during the Civil War and was never rebuilt, and the lower town was in poor condition. However, a sturdy and almost vacant building on higher ground was available; it was known as Lockwood House for a Union general who had stayed there briefly. Brackett installed his family.

Under him were four different schools, in different communities. One was conducted by him and his family in Lockwood House, which was to become Storer College's first building. They taught reading, writing, and arithmetic to the children of former slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and sometimes to their parents. Parents and children sometimes took the same class together, "but the rising generation so far outstripped their ancestors that the old folks became ashamed of themselves, and gave it up."

From this beginning as a one-room school for freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

, Storer developed slowly into a normal school, an academic (college prep) school, then a two-year college, and finally a full-fledged, degree-granting four-year college open to all. Former slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

came to Storer as they were eager to learn to read and write, to help them make their way in a new world of free labor. Some wanted to learn new skills and leave the agricultural fields where most had worked.

The founding of the school was related to a larger national effort by Northern philanthropic organizations and the government's Freedmen's Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was a U.S. government agency of early post American Civil War Reconstruction, assisting freedmen (i.e., former enslaved people) in the ...

to set up schools in order to educate the millions of enslaved African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

freed by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished Slavery in the United States, slavery and involuntary servitude, except Penal labor in the United States, as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed ...

. From Harpers Ferry, Reverend Brackett directed the efforts of dedicated missionary teachers, who provided a basic education to thousands of former slaves congregated in the relatively safe haven of the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The Valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the east ...

by the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

Charter

Dedicated as they were, these few teachers could not begin to meet the educational needs of thefreedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

in the area. Across the South, education of freedmen was an urgent priority within their communities. By 1867, some 16 teachers struggled to educate 2,500 students in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The Valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the east ...

. Reverend Brackett realized that he needed to train African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

teachers.

In 1867, Reverend Brackett's school came to the notice of John Storer, a philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

, who like Brackett was from Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. At the suggestion of Oren B. Cheney

Oren Burbank Cheney (December 10, 1816 – December 22, 1903) was an American politician, minister, and statesman who was a key figure in the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist movement in the United States during the later 19th cent ...

, founder and president of Bates College

Bates College () is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. Anchored by the Historic Quad, the campus of Bates totals with a small urban campus which includes 33 Victorian ...

, a Free Will Baptist school in Maine, Storer offered a $10,000 grant to the Free Will Baptists for "a school which might eventually become a College, to be in located in one of the Southern States, at which youth could be educated without distinction of race or color", if the Freewill Baptists matched his $10,000 donation. His heirs later added $1,000 for a library.

The money was raised, and by March 1868 Storer received its state charter, which was approved in the Legislature by a vote of 13–6, though the phrase "without distinction of race or color" was fiercely debated. At the same time the institution was authorized to operate as a normal school, training teachers for the "colored schools". "Storer College, Normal Department" opened its doors in October of that year. It was sometimes referred to informally as Storer Normal School.

According to its Trustees, in 1870:

Brackett was principal of the school until 1896. He remained Storer's Treasurer and member of the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees until his death in 1910.

Armory buildings and land

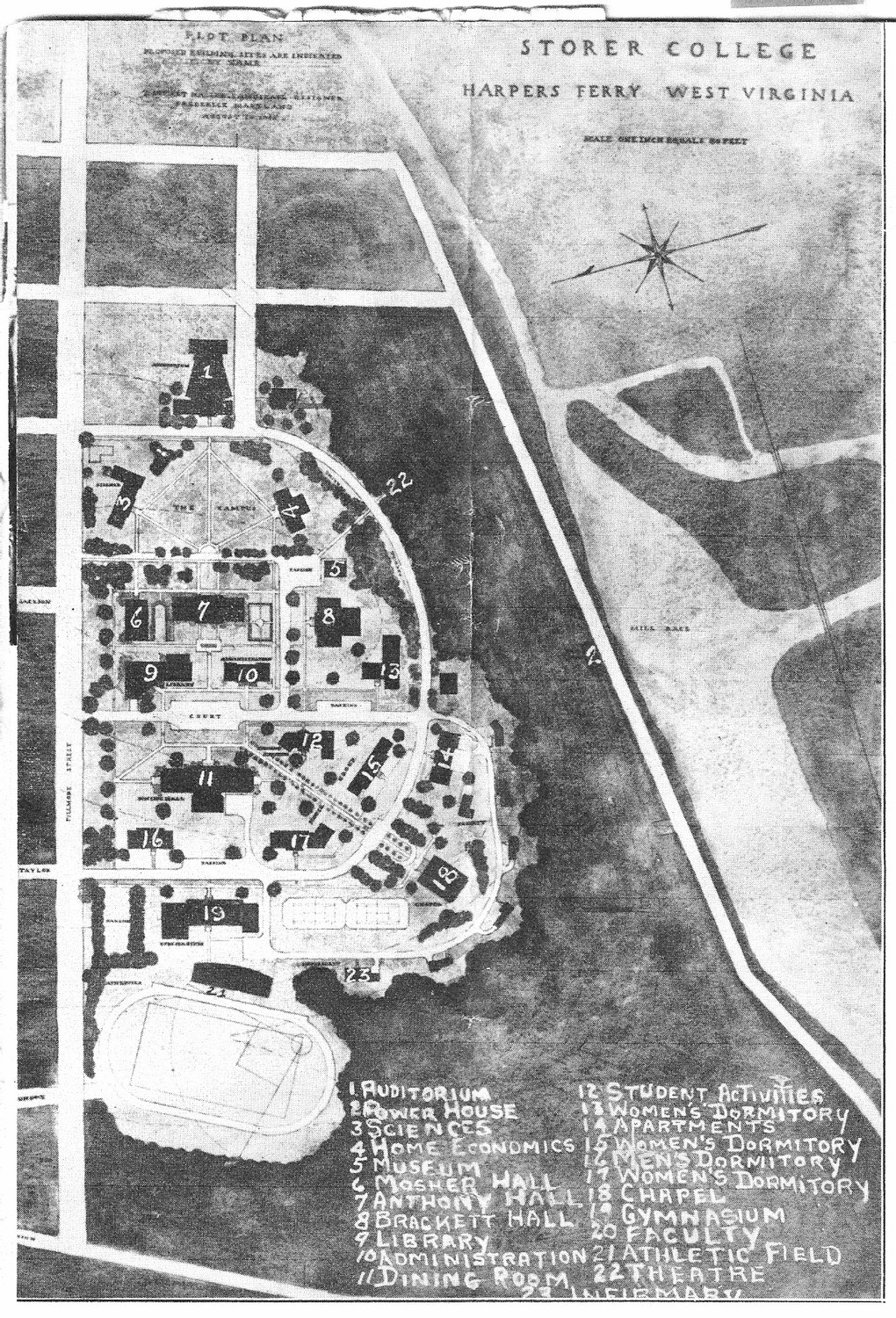

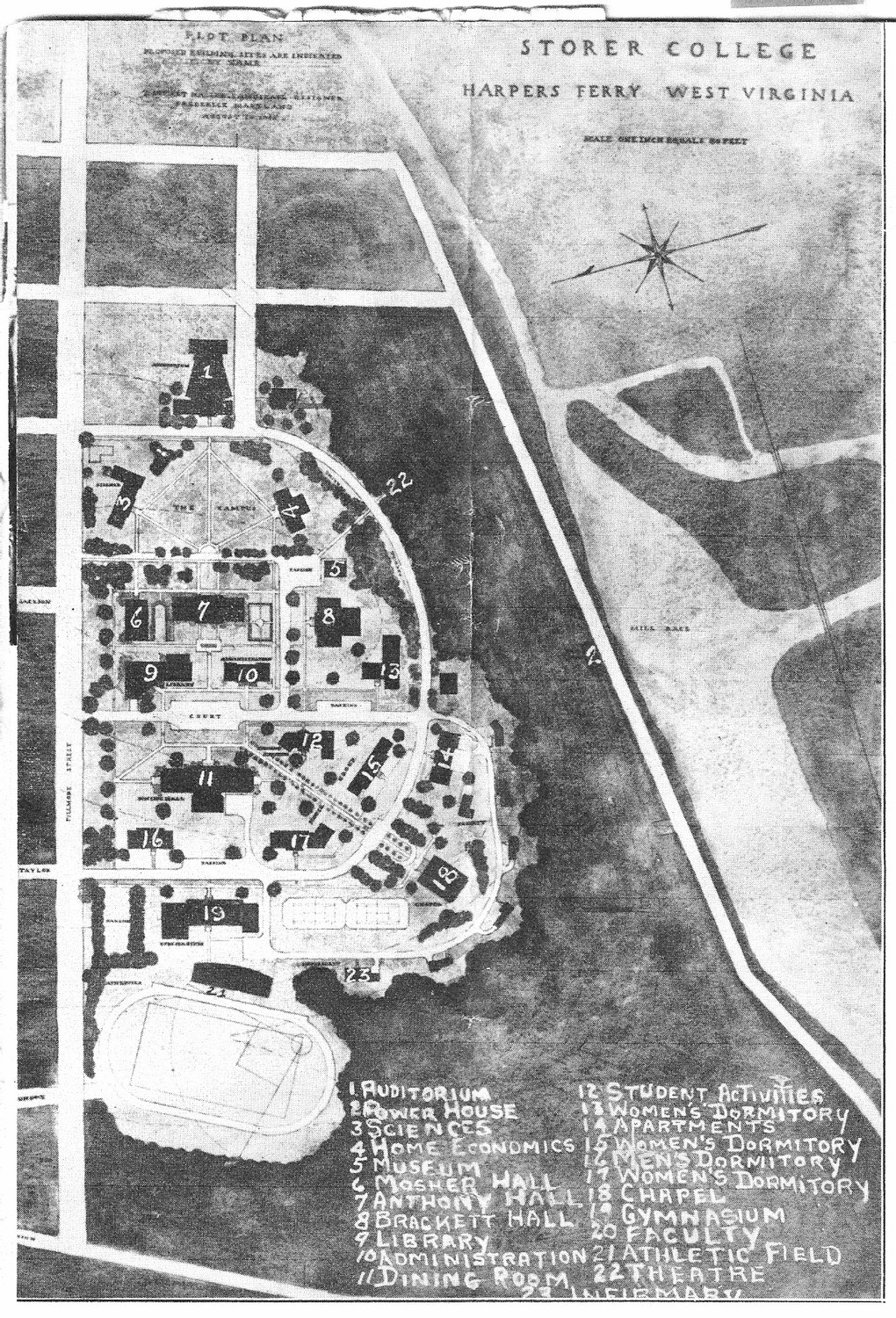

According to a bill signed by President Andrew Johnson on December 15, 1868, the U.S. Government donated to the new Storer College the buildings which became the core of its campus, including the building where Brackett had been teaching his classes. These were four sturdy but vacant buildings— Lockwood House, Brackett House, Morrell House, and the original Anthony Hall—built as housing for workers and managers at the Armory. The College also received the land these buildings were on, which became itscampus

A campus traditionally refers to the land and buildings of a college or university. This will often include libraries, lecture halls, student centers and, for residential universities, residence halls and dining halls.

By extension, a corp ...

.

The College was dedicated on December 22, 1869.

The "College" of Storer College

When founded and for most of its existence, Storer did not offer what in the 21st century would be deemed a college education or college credits. Numerous other colleges, such asTougaloo College

Tougaloo College is a private historically black college in the Tougaloo area of Jackson, Mississippi, United States. It is affiliated with the United Church of Christ and Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). It was established in 1869 by ...

, New-York Central College, West Virginia Wesleyan College, and Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college and conservatory of music in Oberlin, Ohio, United States. Founded in 1833, it is the oldest Mixed-sex education, coeducational lib ...

, also offered instruction at a pre-college level. They were running in essence college-preparatory schools; in the 19th century, in many areas there were no schools preparing students for college. Even in the 20th century, most "junior colleges for Negroes" delivered primarily high-school-level instruction.

At the time, credentials as understood today (2021)—college degrees, for example—were much less important, and the line between college and pre-college instruction was often blurry. Just as today with upper undergraduate and graduate students in the U.S., pre-college and college students might be in the same classroom, taking the same course at the same time, but at a different level of instruction. Medical schools, in the nineteenth century, did not require as prerequisite a college education as understood today (2021). Neither did teaching: normal schools

Normal(s) or The Normal(s) may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Normal'' (2003 film), starring Jessica Lange and Tom Wilkinson

* ''Normal'' (2007 film), starring Carrie-Anne Moss, Kevin Zegers, Callum Keith Rennie, and Andrew Airlie

* ''Norma ...

to train teachers for public elementary schools offered high school level instruction. "I studied at X College" did not necessarily mean, then, that the person had received a college education. No one saw this as a problem, as a college education was much less important, and somewhat unusual. Having studied at the " prep school" gave some of the intellectual benefits and prestige of studying at the college.

Storer was the first school for blacks, ex-slaves or freeborn, in the new state of West Virginia, that was more than a one-room, one-teacher, "ungraded" operation (and there weren't many of those either). There was nothing similar, at least nearby, in any neighboring state. While training elementary school teachers in the normal school, there were also lots of illiterate adult students for the student teachers to instruct. Storer College spent much of its early years teaching reading, writing, and arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

, as almost no one else in the state was providing this instruction to blacks. Storer's Preparatory Division was preparing students for the Normal School, which required literacy. No one saw this as a problem; it was what the West Virginia Legislature expected when they chartered Storer College, described as "a high school for negroes" by a hostile newspaper. No one else in West Virginia was educating those students until the foundation in 1891 of the West Virginia Colored Institute, today West Virginia State University

West Virginia State University (WVSU) is a Public university, public Historically black colleges and universities, historically black, land-grant university in Institute, West Virginia, United States. Founded in 1891 as the West Virginia Color ...

, and in 1895 of the Bluefield Colored Institute, today Bluefield State University. (They are in 2021 the universities in West Virginia with the lowest black enrollment.) They certainly were not welcome at the segregated state normal school, Shepherd College, founded in 1871 in nearby Shepherdstown, West Virginia

Shepherdstown is a town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States, located in the lower Shenandoah Valley along the Potomac River. Home to Shepherd University, the town's population was 1,531 at the time of the 2020 census. The town wa ...

.

In 1938 Storer began offering a curriculum that would lead to a four-year college degree.

Storer College, Jefferson County, and West Virginia

In 1867, that the charter of Storer should say "without distinction of race or color" was "fiercely debated" in the Legislature, and approval of the charter was delayed until March 1868. In 1881 the Legislature directed that the state finance the education of 17 prospective "colored" teachers, justifying this number as being equivalent, relative to West Virginia's colored population at the time, to the ratio of white prospective teachers supported by the state compared to its white population.Finances of the college

The school charged only minimal tuition, $3 per quarter, or $20 for five years. Rooms were only $3 per quarter, so the students' main expense was for their board, estimated at $2–$3 per week. By 1881, the school had already passed through "severe financial embarrassments". Support of the College was the largest single endeavor of the Free Baptists, to which they were "thoroughly committed". In 1867, in addition to chartering it, the West Virginia Legislature appropriated $10,000 (). This was the first appropriation in the state for the education of Negroes above the elementary level. From 1882 to 1892, Storer received $630 from the State of West Virginia, to provide "industrial-type training for Negroes". In 1903, President McDonald referred to the state's "small biennial appropriation" for the same purpose. In 1911–1912, the American Baptist Home Mission Society, which "as a result of doctrinal conflicts" absorbed the Free Baptists in 1911, contributed $1,350 to salaries, and in 1912–1913 was budgeted to contribute $2,750, and for 1913–1914 and 1914–1915, $3,000 each year. In addition, Storer was to receive $1,785 from the sale of Manning Bible School (Cairo, Illinois

Cairo ( , sometimes ) is the southernmost city in the U.S. state of Illinois and the county seat of Alexander County, Illinois, Alexander County. A river city, Cairo has the lowest elevation of any location in Illinois and is the only Illinoi ...

) property,

In 1926, the Legislature appropriated $6,000, which did not even cover half the faculty and administrative salaries. The Free Will Baptist–Home Mission Society, which quashed a fundraising drive, saying they were overextended, contributed $3,000. The Women's Baptist Home Mission Society contributed $3,000, to be used on programs that served women. In 1925 the income from these three main sources totaled $12,096, while expenditures totalled $49,291. "Boarding fees, tuition, and income from the school's farming enterprises, property investments, and donations made up the remainder."

In 1932, the West Virginia Legislature reduced its support from $17,500 to $12,000.

Local hostility

Raising $10,000 turned out to be easy compared to facing local resistance by whites to a " colored school." The Freewill Baptists' other mission school, resembling that in Harpers Ferry, inBeaufort, North Carolina

Beaufort ( , different from that of Beaufort, South Carolina) is a town in Carteret County, North Carolina, United States, and its county seat. Established in 1713 and incorporated in 1723, Beaufort is the fourth oldest town in North Carolina ( ...

, was abandoned after one year due to "lingering Confederate sympathizers". Storer's predecessor in Jefferson County, a school staffed by "Miss Mann", a niece of the educator Horace Mann

Horace Mann (May 4, 1796August 2, 1859) was an American educational reformer, slavery abolitionist and Whig Party (United States), Whig politician known for his commitment to promoting public education, he is thus also known as ''The Father of A ...

, in neighboring Bolivar, only lasted one year because of "militant race prejudice". The town of Harpers Ferry had already rejected a proposal to use Lockwood House "for a school for colored children". Storer's charter aroused intense and violent opposition, and passed by one vote.

Residents of Harpers Ferry tried everything from

Residents of Harpers Ferry tried everything from slander

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making wikt:asserti ...

and vandalism

Vandalism is the action involving deliberate destruction of or damage to public or private property.

The term includes property damage, such as graffiti and defacement directed towards any property without permission of the owner. The t ...

to pulling political strings in their efforts to shut down the school. They petitioned the Legislature to have Storer's charter revoked. One teacher wrote, "it is unusual for me to go to the Post Office without being hooted at, and twice I have been stoned on the streets at noonday." Threats by the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

in the first years caused the faculty and students to carry arms while walking outside. In 1923 the Klan marched past the college. At one point lady teachers required a military escort.

These efforts did not succeed in closing Storer, and eventually, local attitudes changed. In 1891, "the inhabitants of Harper's Ferry hold a true interest and even a pride in the college. Some of its old opponents are now numbered among its most devoted friends. And no person in the community is held in higher honor or greater esteem than Mr. Brackett, once of all men the most hated and despised." However, in 1896 the college ceased renting rooms in the summer to black vacationers, because of local opposition. It continued accommodating white vacationers. The decision was much criticized by students and alumni.

The citizens of Harpers Ferry did not like having John Brown's Fort in their town or the black tourists it attracted, and were happy it was moved to Chicago. They were quite unhappy at its return and then move to the Storer campus.

In 1944 Storer's first black president, Richard Ishmael McKinney, was welcomed with a burning cross on his lawn.

Benevolent paternalism

Some modern scholars view Storer as a reconstructed plantation. Students were taught that they should efface themselves. The school had at one point a Modern Minstrel Company, which performed "Plantation Songs and Melodies” and renditions of numbers like “If the Man in the Moon Was a Coon". President Nathan Brackett said that the school's “humble and illiterate” students "generally show a desire to work and submit to wholesome discipline.” To instill moral character, students were obliged to “march in military columns” between classes, were not permitted to “jump, dance, or scuffle” inside campus buildings or go on “pleasure excursions, rides, or walks in mixed company.” Other rules deterred students from socializing in town or mingling with townspeople. Students did most campus labor, cooking meals, cleaning buildings, maintaining the campus, and caring for the animals on the school farm.NAACP not permitted to post plaque on Fort

Paternalism is particularly linked with Storer's second president, Henry T. McDonald, who tried to smooth over the growing ideological divide between the college and the town. The biggest single such incident was McDonald's full participation in a controversial ceremony, the 1931 dedication of the Heyward Shepherd monument. The monument was the project of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and was intended to support their claim that the enslaved in the South did not desire freedom, and did not support John Brown. McDonald, in his capacity as the president of Storer, made introductory remarks. Two attacks on John Brown then followed; Heyward Shepherd allegedly showed that Brown was wrong and the slaves didn't want freedom. In a dramatic moment, the Storer musical director then praised Brown. McDonald was much criticized in the black press. One newspaper called the college a failure, and asked African Americans to ostracize the college. The ''Afro-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

'' called for his resignation.

In 1932, Max Berber, a founder of the NAACP, presided over the unveiling of a tablet honoring John Brown at the college and referred to Brown as an initiator of the civil rights group. W.E.B. Du Bois had prepared a new plaque in response to the Hayward Shepherd monument, but McDonald, backed by the trustees, refused to allow the NAACP to place this plaque on a wall of the Fort.

The plaque was not erected until 2006. Rather than attaching it to the Fort at its present location, as originally planned, by request from the black community the Park Service located it on the former Storer campus, at the Fort's former location.

Storer graduates

In 1895, the 20 "free schools" in Jefferson County were all taught by Storer graduates. Storer graduates were also found "in other important schools all over the state", and from Maryland in the northeast to Texas in the southwest.An icon for African Americans

During the 88 years it existed, Storer had a great symbolic importance to American blacks. Storer and Harpers Ferry were in fact a black destination. Many black tourists came to Harpers Ferry; there was a hotel catering to them, the Hilltop House, built and managed by a black Storer graduate, Thomas Lovett. In the summer, Storer rented dormitory rooms to tourists and summer boarders, and theBaltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the oldest railroads in North America, oldest railroad in the United States and the first steam engine, steam-operated common carrier. Construction of the line began in 1828, and it operated as B&O from 1830 ...

ran excursion trains from Baltimore and Washington.

Frederick Douglass's speech, 1881

Storer College was a site of various important events in West Virginia and national African-American history. In 1881, the noted abolitionistFrederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

, who had escaped slavery as a young man in the antebellum years and become a noted orator, and who was on Storer's Board of Trustees, delivered his famous speech on abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

John Brown at Storer College. His intent was to raise funds for an endowed

A financial endowment is a legal structure for managing, and in many cases indefinitely perpetuating, a pool of financial, real estate, or other investments for a specific purpose according to the will of its founders and donors. Endowments are ...

John Brown professorship, to be held by a black man. (It never materialized.) There was a "large gathering of people" from Maryland, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and some from as far as New England. They attended a ceremonial laying of the cornerstone for Anthony Hall.

National League of Colored Women visit, 1896

In July 1896, the first national convention of the National League of Colored Women, meeting in Washington, D.C., visited Harpers Ferry, the John Brown Fort, and the college. They passed a resolution condemning "the authorities of Storer College for preventing those who have contributed for the support of Lincoln Hall from using the latter during the present summer, as has been the custom heretofore."Niagara Movement conference, 1906

The

The Niagara Movement

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. The Ni ...

, predecessor of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

, is closely linked to Storer. Formed by a group of leading African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

intellectuals, the Niagara Movement planned a campaign to eliminate discrimination based on race. The movement's leader, W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

, a sociologist with a PhD, rejected the prevalent theory of "accommodation", as opposed to social equality, promoted by Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, and orator. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the primary leader in the African-American community and of the contemporary Black elite#United S ...

, President of the Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU; formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute) is a Private university, private, Historically black colleges and universities, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama, United States. It was f ...

.

The program for its first meeting, celebrated in Fort Erie, Ontario

Fort Erie is a town in the Regional Municipality of Niagara, Niagara Region of Ontario, Canada. The town is located at the south eastern corner of the region, on the Niagara River, directly across the Canada–United States border from Buffal ...

, for fear of disruptions in Buffalo, New York, was typed on the back of Storer letterhead.

The Movement's second conference, the first in the U.S., was held at Storer in 1906. Attendees walked to John Brown's Fort, which shortly thereafter was moved to the campus.

The 1907 meeting would also have been held at Storer, but the school's white administrators would not permit it, because of pressures placed on them.

The Niagara Movement published an annual "Address to the World", demanding voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

(the mass of African Americans in the South had been essentially disenfranchised by the turn of the century), educational and economic opportunities, justice in the courts, and recognition in unions and the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

. Many conservative African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

and white leaders became alienated by their approach, which eroded potential political support. During the 1906 conference, Storer staff expressed discomfort with the group's militancy, and dismay at their tendency to consider even progressive whites as the enemy.

By 1910, five years after it was formed, the Niagara Movement was dissolved. While it did not produce material gains in the civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

arena, its leaders had announced their intention to pursue full civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

, thereby laying a valuable foundation for the development of a more broad-based push for equality.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

(NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

) was formed in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

in 1910 with an interracial board, and many of the members of the failing Niagara Movement quickly joined it. The NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

had many of the same goals of the Niagara Movement

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. The Ni ...

; it also pursued a concentrated program of litigation campaigns in the effort to overturn of barriers to voter registration and voting, end state and local jurisdictions' segregation of housing, gain integrated public transportation and other facilities, seek integrated public education, achieve fair jury trials for blacks, and similar goals.

John Brown's Fort, 1909

John Brown's Fort, the firehouse at the former Harpers Ferry Armory, was moved to the Storer campus in 1909, where it housed the college museum. In 1968, after closure of the college and establishment of theHarpers Ferry National Historical Park

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, originally Harpers Ferry National Monument, is located at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah rivers in and around Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The park includes ...

, the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

moved it back to as close to its original location as possible at the time.

Four-year college degrees

In 1938, under the leadership of school president Henry T. McDonald, Storer became a four-year college. The last new building was completed in 1939-1940. Enrollment peaked at around 400, as Storer and other colleges had struggled during the privations of the Great Depression. The number of students dipped lower with the high rate of participation by young men inWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The college had received some financial support from the state of West Virginia, as it helped educate blacks, who were limited to segregated schools and colleges.

Although the school granted four-year degrees, it never received regional accreditation

Higher education accreditation in the United States is a peer review process by which the validity of degrees and credits awarded by higher education institutions is Quality assurance, assured. It is coordinated by accreditation commissions mad ...

; it never applied. As a result, it was forced to turn away some students. Those who wanted to be doctors, for example, were not admitted. The college was unable to fund the laboratories and other scientific equipment necessary for a pre-med degree.

Closure of the college

It is commonly said that Storer closed because state funding ended after the 1954 ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the ...

'' ruling found segregated public schools to be unconstitutional. There is a kernel of truth to it, but it was but the last of a long series of financial problems. In the first place, Storer College charged no tuition. Its main funding came from the Freewill Baptists. The state of West Virginia helped off and on, but refused to fully fund Storer, or turn it into a state college, because it was religiously affiliated, and because the Constitution of West Virginia prohibited the joint study of black and white students in publicly-supported schools. Storer was a New England project, or a black project, but it was not a West Virginia project. From a West Virginian point of view, Storer's remote location was terrible. The College Trustees chose to retain the religious affiliation and to keep the school open to all. State money then went to fund the new West Virginia Colored Institute (1891) and Bluefield Colored Institute (1895), which were more centrally located and served students that might have attended Storer.

Providing four-year college educations was much more expensive than training primary school teachers. In fact it was beyond the resources of the Freewill Baptists, whose support for the college depended on such things as children's Sunday School contributions.

Storer never achieved regional accreditation

Higher education accreditation in the United States is a peer review process by which the validity of degrees and credits awarded by higher education institutions is Quality assurance, assured. It is coordinated by accreditation commissions mad ...

, and its new (1936) three-year pre-med degrees were not accepted at medical schools. Accreditation required a $100,000 endowment, and Storer had only $20,000. The library and gymnasium were outdated. At the same time, Storer did not have the support of the local community. The hostility from the white community, most of whom wished Brown had never heard of Harper's Ferry, and some of whom made no secret of what they thought of a "nigger college", led to some management decisions that sapped the College's support internally. The College had to sell land to meet expenses. With no state money coming ever again, or so they expected, there was no way to survive. So it closed in 1955.

The college's former campus and buildings were returned to federal control, specifically to the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

(NPS), authorized in a 1962 appropriation, as part of what was then Harpers Ferry National Monument and is now the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, originally Harpers Ferry National Monument, is located at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah rivers in and around Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The park includes ...

. It is currently (2021) one of NPS's four regional training centers.

In 1954, the NAACP achieved a victory with the US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

decision in the ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the ...

'' case, which declared racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

in public schools to be unconstitutional

In constitutional law, constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applic ...

. "The West Virginia Legislature withdrew its annual appropriation from Storer because of the Supreme Court ruling outlawing segregation in public schools, and the resultant policy of integration in state schools. The Legislature ">escribed as "unsympathetic"said the appropriation was intended to finance studies by Negro students at Storer but is now unnecessary because Negroes now are eligible to enroll at other state colleges. The enrollment at Storer has been exclusively Negro." The state appropriation was $20,000. In its final year, the College had 88 students.

Storer had been accumulating debt for a decade, and could not survive without the state appropriation. In June 1955, Storer College closed its doors forever.

Education at Storer

Understanding that former slaves needed to learn more thanthe three Rs

The three Rs are three basic skills taught in schools: reading, writing and arithmetic", Reading, wRiting, and aRithmetic or Reckoning. The phrase appears to have been coined at the beginning of the 19th century.

Origin and meaning

The skills the ...

to function in society, Storer founders intended to provide more than a basic education. According to the first college catalog, students were to "receive counsel and sympathy, learn what constitutes correct living, and become qualified for the performance of the great work of life." In its early years, in the press to expand literacy among the freedmen and their children, Storer taught freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

to read, write, spell, do sums, and to go back into their communities to teach others these lessons.

Storer believed that "morality" went hand in hand with education; for admission, students had to "give satisfactory evidence of a good moral character."

Storer remained primarily a teachers college

Teachers College, Columbia University (TC) is the graduate school of education affiliated with Columbia University, a private research university in New York City. Founded in 1887, Teachers College has been a part of Columbia University since ...

, but added courses in higher education as well as industrial training. Students graduated with a "normal degree," for teaching elementary school students, or an academic degree

An academic degree is a qualification awarded to a student upon successful completion of a course of study in higher education, usually at a college or university. These institutions often offer degrees at various levels, usually divided into und ...

, for those going on to college. Buildings were constructed through the 1930s, with Permelia Eastman Cook Hall, a handsome grey stone building, completed 1939-1940.

In 1911, the West Virginia Legislature struck Storer from its list of accredited normal programs, meaning its graduates could not receive teaching certificates, because "the curriculum did not adequately include enough professional training."

In 1921 Storer was granted junior collegiate status, although it did not award Associate degree

An associate degree or associate's degree is an undergraduate degree awarded after a course of post-secondary study lasting two to three years. It is a level of academic qualification above a high school diploma and below a bachelor's degree ...

s until 1937, and in 1945, senior status. The state accredited its education programs.

Industrial education

Starting in the 1880s, Storer started offering vocational and industrial courses; in 1897 the trustees made industrial education a course of study; there were 137 students that year. This formalization of manual labor at Storer corresponded with a widespread movement in the South that was predicated upon white supremacists notions of black inferiority. ...Manual labor made African Americans fit for citizenship by instilling Christian values and moral character." The school eventually required all normal students to take industrial courses, so that by 1904 it was training more tradespeople than teachers. Henry T. McDonald, also white, in 1899 became Storer's second president. He strongly advocated manual-labor education, overseeing major aspects of the school's transition.Faculty

The Storer College Alumni Association has published on its Web site a list of all the faculty and other employees. In 1871 the faculty was the following: * N. C. Brackett, Principal (arithmetic, philosophy, and political economy) * A. H. Morrell (Bible history and vocal music) * Lura E. Brackett, Preceptress (English grammar, algebra, and botany) (sister of N. C. Brackett) * Louise Wood Brackett (Latin and drawing) (wife of N. C. Brackett) * Lizzie Morell (instrumental music) Plus various substitutes, assistants, and amatron

Matron is the job title of a very senior or the chief nurse in a hospital in several countries, including the United Kingdom, and other Commonwealth countries and former colonies.

Etymology

The chief nurse, in other words the person in charge ...

.

Hamilton Hatter, an African American from Jefferson County, first studied at Storer, then received a bachelor's degree from Bates College

Bates College () is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. Anchored by the Historic Quad, the campus of Bates totals with a small urban campus which includes 33 Victorian ...

in 1888 (where he ran a sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logging, logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes ...

). He then joined the faculty of Storer, establishing the Industrial Department, teaching carpentry as well as Greek, Latin, and mathematics. Hatter left in 1896 to become the first principal of Bluefield Colored Institute. He was a trustee of Storer from 1891 until 1906.

The Bracketts' daughters, Mary Brackett Robertson and Celeste Brackett Newcomer, both taught at the school.

In 1899, the President, the first to be given that title, was Henry F. McDonald. At that time there were 7 full-time and 4 part-time teachers, no courses beyond the high school level, an outdated library, inadequate science labs and equipment, and buildings in desperate need of essential repairs.

During the 1911–1912 academic year, Storer had a faculty of 19: 6 male and 13 female, 10 white and 9 "Negro".

In 1917, the College, "now industrial and normal in character", had about 150 students, and "the faculty is entirely white."

In 1931-32, of the 11 faculty members reported, 5 had a master's degree, and 6 a bachelor's degree.

Richard I. McKinney became Storer's first African-American president in 1944, with the goal of making Storer "a noteworthy four-year institution". He was the College's first employee with a Ph.D. (from Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

). The community welcomed him with a burning cross on his front lawn. Under him, Storer hired additional black faculty; some white faculty had a problem with this. Tensions became worse because McKinney worked to strengthen the College's ties to Africa, including inviting alumnus Nnamdi Azikiwe

Nnamdi Benjamin Azikiwe, (16 November 1904 – 11 May 1996), commonly referred to as Zik of Africa, was a Nigerian politician, statesman, and revolutionary leader who served as the 3rd and first black governor-general of Nigeria from 1960 ...

, President of Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

, as commencement speaker in 1947. Financial solvency was not achieved, and there were tensions with the paternalistic white Board of Directors. McKinney tendered his resignation in 1949, but it was not accepted until the following year, when "the board was...eager to rid Storer of McKinney".

Enrollment

Over the first forty years of the college, enrollment averaged 176. However,

it varied dramatically with the season. For example, in 1873–74, there were 80 fall term students, 167 in the winter term, and for the summer, 124.

The first 8 graduates of the Storer Normal School graduated in 1872. In 1874, a writer observed that the demand for these "colored teachers...is far beyond the capacity of the college with its present means and endowments to supply." By 1877 there were 100 former students teaching, of which 37 were graduates, and many of the remainder returned termittently to complete their education. That year a semi-annual, week-long teachers' institute was inaugurated.

The first graduates of the Academic Department were in 1880.

In 1871 there were 203 enrollees. Counting those still students, Academic Department, 42 students; Normal Department, 174 students; Preparatory Division, 101 students. As of that date there had been 285 different students enrolled. The same year, the '' Spirit of Jefferson'' newspaper reported "more than 150...of all ages and sexes, and...all shades and colors." In 1875, there were 285.

In 1881, a report of the Free-Will Baptists indicates that at Storer there were 200 enrolled students, 62 graduates, level unspecified, and the total number who had enrolled at some time was 800. The report also says that the College had "sent out" over 200 teachers and 25 preachers. In 1882–84 there were 63 enrolled in the three-year normal school training.

In its first 20 years, the school trained hundreds of teachers from West Virginia, Ohio, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

In 1895 there were 250 graduates of the Normal Department.

In 1901 there were 49 male and 73 female students.

In 1931 there were 130 students, 52 at the junior college level and 78 at the high school level.

Over its 90-year history, about 7,000 students enrolled. The Storer College Alumni Association has a 70-page list on its web site. As of the later 19th century students came from 14 states and 4 foreign countries.

Over the first forty years of the college, enrollment averaged 176. However,

it varied dramatically with the season. For example, in 1873–74, there were 80 fall term students, 167 in the winter term, and for the summer, 124.

The first 8 graduates of the Storer Normal School graduated in 1872. In 1874, a writer observed that the demand for these "colored teachers...is far beyond the capacity of the college with its present means and endowments to supply." By 1877 there were 100 former students teaching, of which 37 were graduates, and many of the remainder returned termittently to complete their education. That year a semi-annual, week-long teachers' institute was inaugurated.

The first graduates of the Academic Department were in 1880.

In 1871 there were 203 enrollees. Counting those still students, Academic Department, 42 students; Normal Department, 174 students; Preparatory Division, 101 students. As of that date there had been 285 different students enrolled. The same year, the '' Spirit of Jefferson'' newspaper reported "more than 150...of all ages and sexes, and...all shades and colors." In 1875, there were 285.

In 1881, a report of the Free-Will Baptists indicates that at Storer there were 200 enrolled students, 62 graduates, level unspecified, and the total number who had enrolled at some time was 800. The report also says that the College had "sent out" over 200 teachers and 25 preachers. In 1882–84 there were 63 enrolled in the three-year normal school training.

In its first 20 years, the school trained hundreds of teachers from West Virginia, Ohio, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

In 1895 there were 250 graduates of the Normal Department.

In 1901 there were 49 male and 73 female students.

In 1931 there were 130 students, 52 at the junior college level and 78 at the high school level.

Over its 90-year history, about 7,000 students enrolled. The Storer College Alumni Association has a 70-page list on its web site. As of the later 19th century students came from 14 states and 4 foreign countries.

Curriculum

Storer's first program was the normal program, preparing teachers. In 1872 Storer started its first academic, four-year department, the Seminary Course igh school it taughtclassics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

, including Latin, Greek, and Shakespeare, along with astronomy, algebra, geometry, and botany. This program, which graduated twenty-five students, languished after 1896. An industrial department teaching woodworking, printing, and blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

ing was added in 1886. Domestic science

Home economics, also called domestic science or family and consumer sciences (often shortened to FCS or FACS), is a subject concerning human development, personal and family finances, consumer issues, housing and interior design, nutrition and f ...

became required for females in 1893, and girls were required to sew their own graduation gowns. A separate department of Biblical Literature emerged in 1895.

Starting in 1899, when Storer's second president started, for graduation students had to complete these assigned readings:

* Political philosopher Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

, who supported the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

.

* Abolitionist American writer Noah Webster

Noah Webster (October 16, 1758 – May 28, 1843) was an American lexicographer, textbook pioneer, English-language spelling reformer, political writer, editor, and author. He has been called the "Father of American Scholarship and Education" ...

.

* English Romantic poet

Romantic poetry is the poetry of the Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. It involved a reaction against prevailing Neoclassical ideas of the 18th c ...

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poetry, Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romanticism, Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Balla ...

.

* American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include the poems " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to comp ...

.

* American writer Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He wrote the short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and "The Legend of Sleepy ...

.

* English novelist and abolitionist George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

(pseudonym of Mary Ann Evans).

* The abolitionist American poet John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet ...

.

* Shakespeare.

Student life

From the outset and as late as 1887, students "of any state of advancement", who could "give satisfactory evidence of good moral character", were admitted on any day of the session, and placed by examination. According to Storer's first catalogue (1869), students were to "receive counsel and sympathy, learn what constitutes correct living, and become qualified for the great work of life". Every student was required to have a Bible and to attend chapel, Sunday school, 9 AM prayer, and daily 15-minute assemblies. Students were allowed to attend intermittently, depending on personal responsibility and finances. By 1889 a minimum age of thirteen was set, in 1909 raised to fourteen. Students at Storer were subject to many other rules. Class attendance was mandatory, as was an hour's study before class each morning. Students were not allowed to drop or change classes. Students could not "loiter" on campus, and they were forbidden from leaving the campus during the week, and on weekends were to avoid dances and "walks in mixed company". Women students were not allowed out after dark, could not be seen alone in the company of a man, and required an escort when going to the train station.Buildings

Storer's facilities were described as "bare bones". For example, there was no hot water in the men's dormitory in 1947.Original buildings

Buildings still standing in 2022 are marked in bold. * Four Armory buildings. With the support of Senator and future PresidentJames Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 1881 until Assassination of James A. Garfield, his death in September that year after being shot two months ea ...

, who had studied in a Free Will Baptist school, in 1869 Congress turned over to the War Department, who turned over to the Freedmen's Bureau, and then to Storer, four surviving buildings at Camp Hill, all built by the federal government as housing for Armory employees. They were "dilapidated" after Civil War damage. Additional land was purchased.

** Lockwood House, described as "one of the finest residences in Harpers Ferry", was built in 1847–48 as quarters for the Armory paymaster. It became a Clayton Hospital, a military hospital, in 1862, and later became the headquarters of Union General Henry Hayes Lockwood, who lived there only three months. Subsequently it was used by Major General Philip H. Sheridan. Nathan Brackett set up his first school in 1865, he personally teaching a roomful of illiterate freedmen to read. There was a hole in the roof from a shell and windows missing, and the second floor could not be used until it was repaired. In 1867 Brackett opened the "Storer Normal School in this building. By 1869 the classroom and chapel had been relocated to Anthony House, and Lockwood became primarily a dormitory. In the summer rooms were rented out, to raise money. In 1883 a third floor with a girls' dormitory was added. in 1941 it became a faculty apartment building. However, it fell into disuse and when the College closed in 1955 was in "considerable disrepair".

** The original Brackett House, built in 1858, was formerly the superintendent's clerks' quarters. In 1880, it was occupied by principal Brackett, his family of 6, 3 servants, and 13 female students. A new girls' dormitory was built. After this building was destroyed by fire, a replacement building was buil in 1909–10. It was first called New Lincoln Hall and then renamed for Brackett in 1938. This building was demolished in 1962. In 1995 a Park Service building occupies the site.

** Morell House was built in 1858, and was formerly the paymaster's clerk's quarters. It is named for Alexander H. Morrell, who was a Free Will Baptist preacher sent to Harpers Ferry by the church to help in the education of freemen. In 1870, Reverend Morell and his wife had 20 to 27 girls boarding with them. In 1995 it held the office of the Superintendent of Harpers Ferry National Historic Park, and other administrative offices.

** The north wing of Anthony House, later Anthony Memorial Hall, was the Armory superintendent's quarters. President Lincoln spent the night of October 2, 1862, at Anthony House; Lincoln was visiting General George McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey and as Commanding General of the United States Army from November 1861 to March 186 ...

, in Maryland. In 1870 the school and mission headquarters were moved here from Lockwood House. Deacon Lewis W. Anthony donated $5,000 () for a large new addition, containing the main library, music rooms, a lecture hall, and administrative offices, for which reason the building was dedicated to him. The building had a chapel (plus an "old chapel"), lecture rooms, library, and quarters for the principal's family. On May 30, 1881, the day preceding the laying of the cornerstones of the two new annexes, Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

gave his famous John Brown address. In 1882, a visitor noted that in the chapel, behind the pulpit, a large portrait of John Brown held the "place of honor", accompanied by portraits of abolitionist senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, and " General Garfield". It was rehabilitated by the NPS in 1963, and houses the Mather Training Center.

Additional buildings

*The Bird-Brady House served as a private residence for teachers and families associated with the school. Originally occupied by white Baptists, the house is named after Elizabeth Bird and Mabel Brady, sisters who graduated from the college and worked there as administrators in the 1940s and 50s. From the 1940s on, African-Americans began to take a stronger leadership role in running the college. The building was bought by the National Park Service in 1962, but Bird and Brady continue to live there until at least 1970. Afterwards, the building was converted for use as office space as part of the NPS's Harpers Ferry Center. * Lincoln Hall, the boys' dormitory, was a frame building built in 1870–71. It contained 34 double rooms on 3 stories. In the summer rooms were rented to tourists and boarders, to raise money. It burned to the ground in 1909. It was replaced in 1909–10 with New Lincoln Hall, housing 100 students, renamed Brackett Hall in 1938. It was demolished in 1962, and an NPS building is on the site. *In 1889 the school "very much need da heating system". The school had no running water, and the town of Harper's Ferry was "too poor" to put in a water works system. They have therefore no protection from fire. The Industrial Building was practically completed, and they were seeking $1,000 to buy equipment for it. A physics and chemistry laboratory was set up in the DeWolf Industrial Building, and they are raising money for a carpentry building. *The Lewis W. Anthony Industrial Building was built in 1902 and was originally used for the college's industrial training classes, but was converted to be its library in 1929, part of the school's movement away from being a trade school towards a more academically-oriented program typical of a four-year liberal arts college. The building is now called the Anthony Library and serves as the library for the National Park Services's Harpers Ferry Center. * John Brown's Fort, "an important symbol of the struggle African Americans had faced to win their freedom", was moved to the campus in 1909, the 50th anniversary of John Brown's raid, and remained there through the College's closure in 1955. It "was a tourist destination—almost a shrine—for African Americans in the late nineteenth century." It contained the College museum, with display cases, and pictures of Brown, Lincoln, Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Kate Field (who got it returned to Harpers Ferry, from Chicago). In 1968 the National Park Service moved it to its present location in lower Harpers Ferry. * Lewis W. Anthony Industrial Arts Building, built in 1903, housed theblacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

and carpenter's shops, and laboratories. It became the college library in 1929. The NPS uses it as a library.

* A report of 1901 said that "a laboratory for physics and chemistry has been fitted up in the DeWolf Industrial Building".

* Myrtle Hall, the girls' dormitory, was completed in 1879. It had 35 rooms for 60 women and several te achers. with cooking and laundry facilities in the basement. It was named for the Freewill Baptists' youth publication, ''The Myrtle''. Renamed Mosher Hall (Mrs. Mosher edited ''The Myrtle'') when it became the boys' dorm in the 20th century, it was torn down by the National Park Service in 1962.

* In 1940, Permelia Eastman Cook Hall opened. It houses a new physics laboratory and the home economics department. In 1995 it was used as a dormitory for visiting NPS personnel, but it is now used for offices, including those of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail

The Appalachian Trail, also called the A.T., is a hiking trail in the Eastern United States, extending almost between Springer Mountain in Georgia and Mount Katahdin in Maine, and passing through 14 states.Gailey, Chris (2006)"Appalachian T ...

.

* The Science Building, built 1947, and the DeWolf Industrial Building were also razed by the NPS.

Legacy

In 1962, Congress appropriated funds for the National Park Service to acquire the surviving buildings on campus, some occupied bysquatters

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building (usually residential) that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there wer ...

, as part of what is now known as Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, originally Harpers Ferry National Monument, is located at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah rivers in and around Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The park includes ...

. It had been established in 1944 as a National Monument, taking in much of the declining town.

As part of this change, in 1964, the movable physical assets of the college were transferred to the historically white Alderson-Broaddus College, a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

college, and used to establish scholarships for black students. The college's endowment was merged with Virginia Union University

Virginia Union University is a Private university, private Historically black colleges and universities, historically black university in Richmond, Virginia.

History