Stone Of Scone on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Stone of Scone (; gd, An Lia Fàil; sco, Stane o Scuin)—also known as the Stone of Destiny, and often referred to in England as The Coronation Stone—is an oblong block of red

In 1296, during the

In 1296, during the

Highlights: The Stone of Destiny

Edinburgh Castle website

sacred kingship in the 21st century {{DEFAULTSORT:Stone Of Scone Individual thrones

sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

that has been used for centuries in the coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

of the monarchs of Scotland

The monarch of Scotland was the head of state of the Kingdom of Scotland. According to tradition, the first King of Scots was Kenneth I MacAlpin (), who founded the state in 843. Historically, the Kingdom of Scotland is thought to have grown ...

. It is also known as Jacob's Pillow Stone and the Tanist

Tanistry is a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist ( ga, Tánaiste; gd, Tànaiste; gv, Tanishtey) is the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the (royal) Gaelic patrilineal dynasties of Ir ...

Stone, and as in Scottish Gaelic.

Historically, the artefact was kept at the now-ruined Scone Abbey

Scone Abbey (originally Scone Priory) was a house of Augustinian canons located in Scone, Perthshire (Gowrie), Scotland. Dates given for the establishment of Scone Priory have ranged from 1114 A.D. to 1122 A.D. However, historians have long be ...

in Scone

A scone is a baked good, usually made of either wheat or oatmeal with baking powder as a leavening agent, and baked on sheet pans. A scone is often slightly sweetened and occasionally glazed with egg wash. The scone is a basic component ...

, near Perth, Scotland

Perth (Scottish English, locally: ; gd, Peairt ) is a city in central Scotland, on the banks of the River Tay. It is the administrative centre of Perth and Kinross council area and the historic county town of Perthshire. It had a population o ...

. It was seized by Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

's forces from Scone during the English invasion of Scotland in 1296, and was used in the coronation of the monarchs of England

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself King of the Anglo-Sax ...

as well as the monarchs of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, following the Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name usually now given to the treaty which led to the creation of the new state of Great Britain, stating that the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland were to be "United i ...

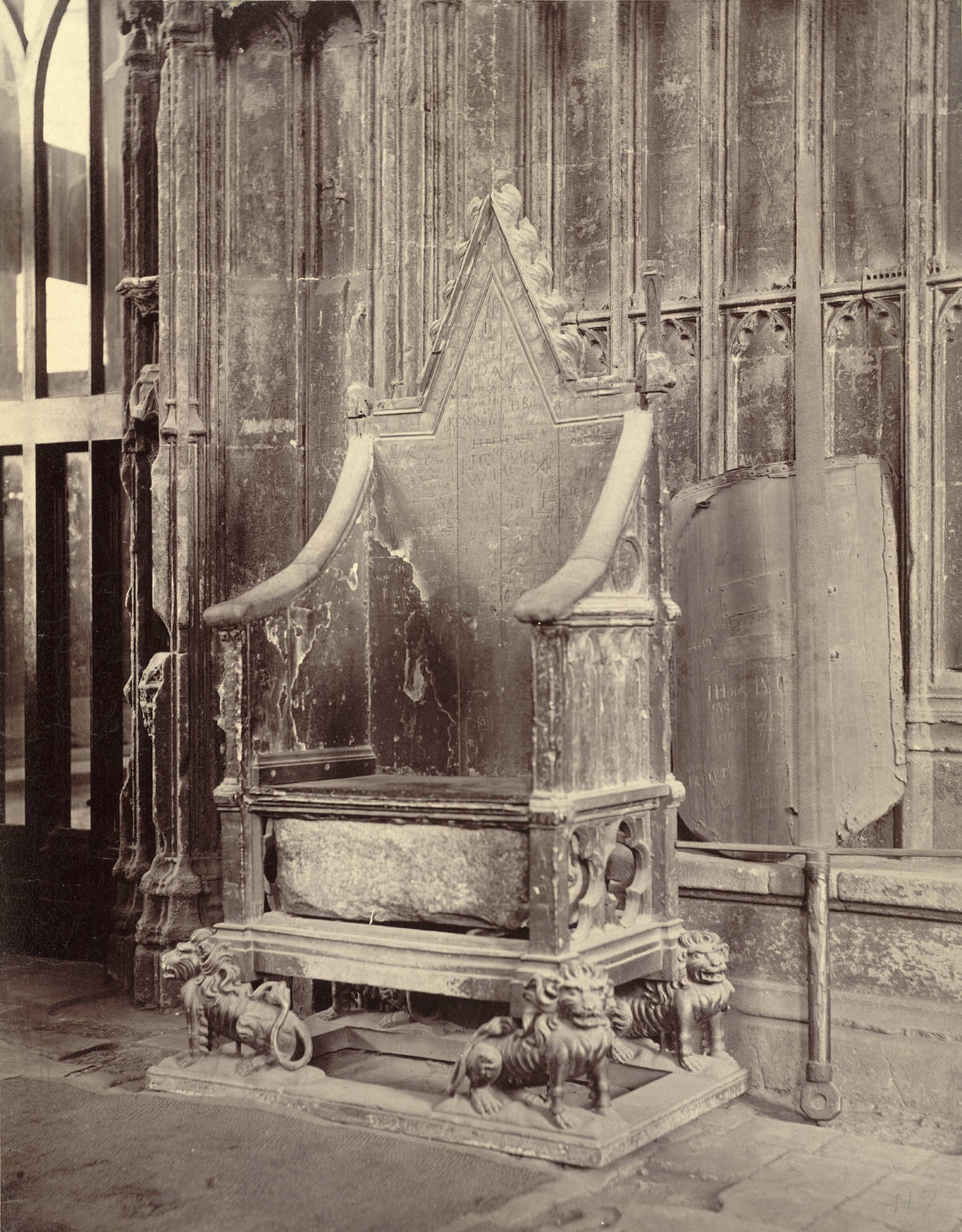

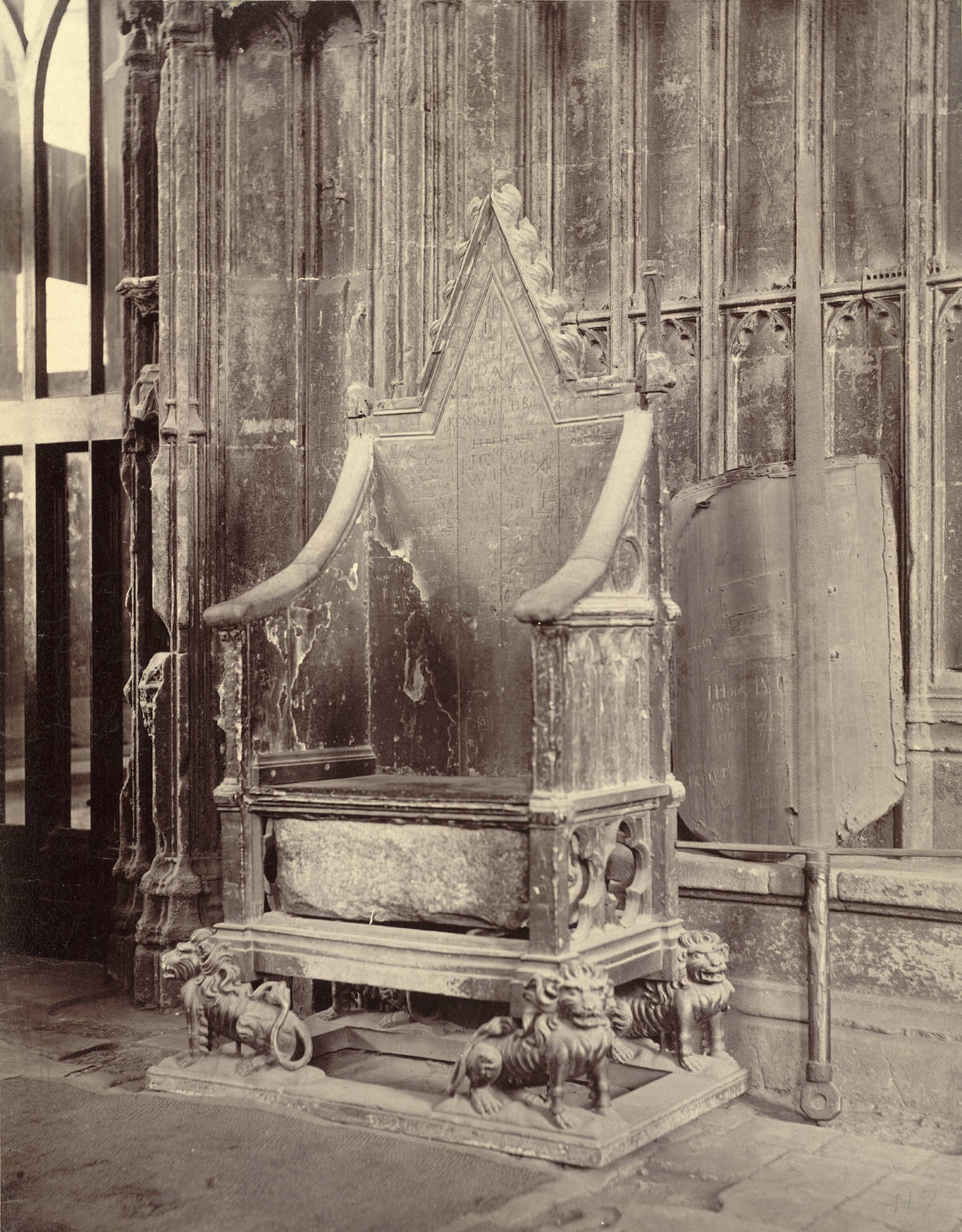

of 1707. Its size is by by and its weight is approximately . A roughly incised cross is on one surface, and an iron ring at each end aids with transport. Monarchs used to sit on the Stone of Scone itself until a wooden platform was added to the Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

in the 17th century.

In 1996, the British Government decided to return the stone to Scotland, when not in use at coronations, and it was transported to Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

, where it is now kept with the Scottish Crown Jewels.

Tradition and history

Origin and legends

In the 14th century the English cleric and historian Walter Hemingford identified the previous location of the Scottish coronation stone as the monastery of Scone, north of Perth: Various theories and legends exist about the stone's history prior to its placement in Scone. One story concerns Fergus, son of Erc, the firstKing of the Scots

The monarch of Scotland was the head of state of the Kingdom of Scotland. According to tradition, the first King of Scots was Kenneth I MacAlpin (), who founded the state in 843. Historically, the Kingdom of Scotland is thought to have grown ...

() in Scotland, whose transport of the Stone from Ireland to Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

, where he was crowned on it, was recorded in a 15th-century chronicle. Some versions identify the stone brought by Fergus with the Lia Fáil

The (; meaning "Stone of Destiny" or "Speaking Stone" to account for its oracular legend) is a stone at the Inauguration Mound ( ga, an Forrad) on the Hill of Tara in County Meath, Ireland, which served as the coronation stone for the High K ...

(Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

for "stone of destiny") used at Tara for inaugurating the High Kings of Ireland. Other traditions contend that the Lia Fáil remains at Tara. (''Inis Fáil'', "The Island of Destiny", is one of the traditional names of Ireland.) Other legends place the origins of the Stone in Biblical times and identify it as the Stone of Jacob

The Stone of Jacob appears in the Book of Genesis as the stone used as a pillow by the Israelite patriarch Jacob at the place later called Bet-El. As Jacob had a vision in his sleep, he then consecrated the stone to God. More recently, the stone ...

, taken by Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. J ...

from Bethel while on the way to Haran

Haran or Aran ( he, הָרָן ''Hārān'') is a man in the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. He died in Ur of the Chaldees, was a son of Terah, and brother of Abraham. Through his son Lot, Haran was the ancestor of the Moabites and Ammonite ...

(Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

28:10–22). This very same Stone of Jacob was then supposedly taken to ancient Ireland by the prophet Jeremiah

Jeremiah, Modern: , Tiberian: ; el, Ἰερεμίας, Ieremíās; meaning " Yah shall raise" (c. 650 – c. 570 BC), also called Jeremias or the "weeping prophet", was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewish ...

.

Contradicting these legends, geologists have proven that the stone taken by Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassa ...

to Westminster is a "lower Old Red Sandstone

The Old Red Sandstone is an assemblage of rocks in the North Atlantic region largely of Devonian age. It extends in the east across Great Britain, Ireland and Norway, and in the west along the northeastern seaboard of North America. It also exte ...

", which was quarried in the vicinity of Scone. Doubts over the authenticity of the stone at Westminster have existed for a long time: a blog

A blog (a truncation of "weblog") is a discussion or informational website published on the World Wide Web consisting of discrete, often informal diary-style text entries (posts). Posts are typically displayed in reverse chronological order ...

post by retired Scottish academic and writer of historical fiction, Marie MacPherson, shows that they date back at least two hundred years.

A letter to the editor of the ''Morning Chronicle

''The Morning Chronicle'' was a newspaper founded in 1769 in London. It was notable for having been the first steady employer of essayist William Hazlitt as a political reporter and the first steady employer of Charles Dickens as a journalist. It ...

'', dated 2 January 1819, states:

Dunsinane Hill

Dunsinane Hill ( ) is a hill of the Sidlaws near the village of Collace in Perthshire, Scotland. It is mentioned in Shakespeare's play ''Macbeth'', in which Macbeth is informed by a supernatural being, "Macbeth shall never vanquished be, until ...

has the remains of a late prehistoric hill fort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Roma ...

, and this has historical associations with Macbeth, but no remains dating to the 11th century have been identified on the hill.

Westminster Abbey

In 1296, during the

In 1296, during the First Scottish War of Independence

The First War of Scottish Independence was the first of a series of wars between English and Scottish forces. It lasted from the English invasion of Scotland in 1296 until the ''de jure'' restoration of Scottish independence with the Treaty o ...

, King Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

of England took the stone as spoils of war and removed it to Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, where it was fitted into a wooden chair – known as the Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

or King Edward's Chair – on which most subsequent English and then British sovereigns have been crowned. Edward I sought to claim the status of the "Lord Paramount" of Scotland, with the right to oversee its King.

Some doubt exists over the stone captured by Edward I. The Westminster Stone theory

The Westminster Stone theory is the belief held by some historians and scholars that the stone which traditionally rests under the Coronation Chair is not the true Stone of Destiny but a 13th-century substitute. Since the chair has been locate ...

posits that the monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

s at Scone Palace

Scone Palace is a Category A-listed historic house near the village of Scone and the city of Perth, Scotland. Built in red sandstone with a castellated roof, it is an example of the Gothic Revival style in Scotland.

Scone was originally the s ...

hid the real stone in the River Tay

The River Tay ( gd, Tatha, ; probably from the conjectured Brythonic ''Tausa'', possibly meaning 'silent one' or 'strong one' or, simply, 'flowing') is the longest river in Scotland and the seventh-longest in Great Britain. The Tay originates ...

, or buried it on Dunsinane Hill

Dunsinane Hill ( ) is a hill of the Sidlaws near the village of Collace in Perthshire, Scotland. It is mentioned in Shakespeare's play ''Macbeth'', in which Macbeth is informed by a supernatural being, "Macbeth shall never vanquished be, until ...

, and that the English troops were tricked into taking a substitute. Some proponents of this theory claim that historic descriptions of the stone do not match the present stone.

In the 1328 Treaty of Northampton between the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a la ...

and the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

, England agreed to return the captured stone to Scotland; rioting crowds prevented it from being removed from Westminster Abbey. The stone remained in England for another six centuries. When King James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

assumed the English throne as James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland as James I from the Union of the Crowns, union of the Scottish and Eng ...

, he was crowned at Westminster Abbey on the stone. For the next century, the Stuart kings and queens of Scotland once again sat on the stone – but at their coronation as kings and queens of, and in, England.

1914 suffragette bombing

On 11 June 1914, as part of thesuffragette bombing and arson campaign

Suffragettes in Great Britain and Ireland orchestrated a bombing and arson campaign between the years 1912 and 1914. The campaign was instigated by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), and was a part of their wider campaign for women's ...

of 1912-1914, suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

s of the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

planted a bomb loaded with nuts and bolts to act as shrapnel next to the Coronation Chair and Stone; no serious injuries were reported in the aftermath of the subsequent explosion despite the building having been busy with 80-100 visitors, but the deflagration blew off a corner of the Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

and caused the Stone to break in half – although this was not discovered until 1950, when four Scottish nationalists broke into the church to steal the stone and return it to Scotland. Two days after the Westminster Abbey bombing, a second suffragette bomb was discovered before it could explode in St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

.

Early 20th century

Concerns about it being damaged or destroyed by German air raids during theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

resulted in the Coronation Chair being moved to Gloucester Cathedral

Gloucester Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Peter and the Holy and Indivisible Trinity, in Gloucester, England, stands in the north of the city near the River Severn. It originated with the establishment of a minster dedicated to S ...

for the duration of the war. Meanwhile, concerns about the propaganda implications of the stone falling into German hands led to it being hidden behind ancient lead coffins in a burial vault under Abbot Islip’s Chapel, situated off the north ambulatory

The ambulatory ( la, ambulatorium, ‘walking place’) is the covered passage around a cloister or the processional way around the east end of a cathedral or large church and behind the high altar. The first ambulatory was in France in the 11th ...

of the abbey. Other than the Dean, Paul de Labilliere

Paul Fulcrand Delacour De Labillière (22 January 187928 April 1946) was the second Bishop of Knaresborough from 1934 to 1937; and, subsequently, Dean of Westminster.

Career

Born on 22 January 1879 into a legal family (his father was a bar ...

and the Surveyor of the Fabric of Westminster Abbey

The post of Surveyor of the Fabric of Westminster Abbey was established in 1698. The role is an architectural one, with the current holder being responsible for the upkeep and maintenance of the Abbey and its buildings. In the past, the role has i ...

, Charles Peers, only a few other people knew of its hiding place. Worried that the secret could be lost if all of them were killed during the war, Peers drew up three maps showing its location. Two were sent in sealed envelopes to Canada, one to the Canadian Prime Minister William King, who deposited it in the Bank of Canada’s vault in Ottawa. The other went to the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario

The lieutenant governor of Ontario (, in French: ''Lieutenant-gouverneur'' (if male) or ''Lieutenante-gouverneure'' (if female) ''de l'Ontario'') is the viceregal representative in Ontario of the , who operates distinctly within the province bu ...

, who stored his envelope in the Bank of Montreal in Toronto. Once he had received word that the envelopes had been received, Peers destroyed the third map, which he had been keeping at his bank.

Peers later received a suggestion via the Office of Works that the Stone should be sent to Scotland for safekeeping:

“I trust the Office of Works will not lend itself to this attempt by the Scotch to get hold of the Stone by a side wind. You cannot be so simple as not to know that this acquisitive nation have ever since the time of Edward I been attempting by fair means or foul, to get possession of the Stone, and during my time at Westminster we have received warnings from the Police that Scottish emissaries were loose in London, intending to steal the Stone and we had better lock up the Confessor’s Chapel, where it is normally kept.”

Removal

On Christmas Day 1950, a group of four Scottish students ( Ian Hamilton,Gavin Vernon

Gavin Harold Russell Vernon (11 August 1926 – 19 March 2004) was a Scottish engineer who along with his accomplices, removed the Stone of Scone from Westminster Abbey in London on Christmas Day 1950 and took the Stone to Scotland.

Background ...

, Kay Matheson

Kay Matheson (7 December 1928 – 6 July 2013) was a Scottish teacher, political activist, and Gaelic scholar. She was one of the four University of Glasgow students involved in the 1950 removal of the Stone of Scone.

Life

Matheson was born ...

, and Alan Stuart) removed the stone from Westminster Abbey, intending to return it to Scotland. During the removal process, the stone broke into two pieces. After burying the greater part of the Stone in a Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

field, where they camped for a few days, they uncovered the buried stone and returned to Scotland, along with a new accomplice, John Josselyn.

According to one American diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or internati ...

who was posted in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

at the time, the stone was briefly hidden in a trunk in the basement of the consulate's Public Affairs Officer, unbeknownst to him, then brought up further north. The smaller piece was similarly brought north at a later time. The entire stone was passed to a senior Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

politician, who arranged for the Glasgow stonemason

Stonemasonry or stonecraft is the creation of buildings, structures, and sculpture using stone as the primary material. It is one of the oldest activities and professions in human history. Many of the long-lasting, ancient shelters, temples, mo ...

Robert Gray to repair it professionally.

The British Government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

ordered a major search for the stone, but was unsuccessful. The stone was left by those that had been hiding it on the altar of Arbroath Abbey

Arbroath Abbey, in the Scottish town of Arbroath, was founded in 1178 by King William the Lion for a group of Tironensian Benedictine monks from Kelso Abbey. It was consecrated in 1197 with a dedication to the deceased Saint Thomas Becket, who ...

on 11 April 1951, a property owned by the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

. Once the London police were informed of its whereabouts, the stone was returned to Westminster four months after its removal. Afterward, rumours circulated that copies of the stone had been made, and that the returned stone was not the original.

Return to Scotland

On 3 July 1996, in response to a growing discussion around Scottish cultural history, the British Government announced that the stone would return to Scotland, 700 years after it had been taken. On 15 November 1996, after a handover ceremony at the border between representatives of the Home Office and of theScottish Office

The Scottish Office was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom from 1885 until 1999, exercising a wide range of government functions in relation to Scotland under the control of the Secretary of State for Scotland. Following the e ...

, the stone was transported to Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

. An official handover ceremony occurred in the Castle on 30 November 1996, St Andrew's Day

Saint Andrew's Day, also called the Feast of Saint Andrew or Andermas, is the feast day of Andrew the Apostle. It is celebrated on 30 November (according to Gregorian calendar) and on 13 December (according to Julian calendar). Saint Andrew is ...

, to mark the arrival of the stone. Prince Andrew, Duke of York

Prince Andrew, Duke of York, (Andrew Albert Christian Edward; born 19 February 1960) is a member of the British royal family. He is the younger brother of King Charles III and the third child and second son of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince ...

, representing Queen Elizabeth II, formally handed over the Royal Warrant transferring the stone into the safekeeping of the Commissioners for the Regalia. It currently remains alongside the crown jewels of Scotland, the Honours of Scotland, in the Crown Room of Edinburgh Castle.

Future public display

As part of a consultation in 2019, the Scottish Government asked the public for their views on the preferred future location for public display of the Stone of Scone. Two options were proposed: featuring as the centrepiece of a proposed new museum inPerth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

(a £23 million redevelopment of the former Perth City Hall) or remaining at the present location at Edinburgh Castle in a major redevelopment of the existing display.

In December 2020, the Scottish Government announced the stone would be relocated to Perth City Hall

Perth City Hall is an events facility in King Edward Street, Perth, Scotland. It is a Category B listed building. Built in 1914, it closed in 2005 and underwent a major renovation, beginning in 2018, including the introduction of a museum in par ...

.

In September 2022 and following the death of Queen Elizabeth II

On 8 September 2022, at 15:10 BST, Elizabeth II, Queen of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms, and the longest-reigning British monarch, died of old age at Balmoral Castle in Scotland, at the age of 96. The Queen's death wa ...

, it was announced that the stone would be temporarily returned to Westminster Abbey for the coronation of Charles III

The coronation of Charles III and his wife, Camilla, as King and Queen of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms will take place on Saturday, 6 May 2023, at Westminster Abbey. King Charles III acceded to the throne on 8 Septemb ...

.

In popular culture

Film and television

* In December 1980 the film ''The Pinch'' aired onBBC 2

BBC Two is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network owned and operated by the BBC. It covers a wide range of subject matter, with a remit "to broadcast programmes of depth and substance" in contrast to the more mainstream an ...

.

* In the episode "Pendragon" of the animated series '' Gargoyles'', King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

returns to Britain in the 20th century and receives instructions from the Stone on how to locate Excalibur

Excalibur () is the legendary sword of King Arthur, sometimes also attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. It was associated with the Arthurian legend very early on. Excalibur and the Sword in th ...

.

* The season 5, episode 15 story arc of '' Highlander: The Series'' retells how Duncan MacLeod was involved in the theft and return of the stone.

* The Stone of Scone's removal from Westminster Abbey and return to Scotland is the subject of the 2008 film '' Stone of Destiny''.

* In the 2010 film ''The King's Speech

''The King's Speech'' is a 2010 British historical drama film directed by Tom Hooper and written by David Seidler. Colin Firth plays the future King George VI who, to cope with a stammer, sees Lionel Logue, an Australian speech and language ...

'', Lionel Logue

Lionel George Logue, (26 February 1880 – 12 April 1953) was an Australian speech and language therapist and amateur stage actor who helped King George VI manage his stammer.

Early life and family

Lionel George Logue was born in College To ...

(Geoffrey Rush

Geoffrey Roy Rush (born 6 July 1951) is an Australian actor. He is known for his eccentric leading man roles on stage and screen. He is among 24 people who have won the Triple Crown of Acting, having received an Academy Award, a Primetime Em ...

) intentionally provokes George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952. ...

(Colin Firth

Colin Andrew Firth (born 10 September 1960) is an English actor and producer. He was identified in the mid-1980s with the " Brit Pack" of rising young British actors, undertaking a challenging series of roles, including leading roles in '' A M ...

) by sitting in the Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

and propping his feet on the Stone.

* It also appears in the final two episodes of ''Hamish Macbeth

Hamish Macbeth is the lackadaisical police constable of the fictional Scottish Highland town of Lochdubh, in a series of murder mystery novels created by M. C. Beaton (Marion Chesney).

Considered by many to be a useless, lazy moocher, Macbeth ...

'', "Destiny" parts 1 and 2.

* Episode 2 "Stoned" of the '' Stuff the British Stole'' series hosted by Marc Fennell

Marc Fennell is an Australian film critic, technology journalist, radio personality, author and television presenter. Fennell is a co-anchor of '' The Feed'' and the host of ''Mastermind''.

Career Film critic

In 2002, Fennell was a winner o ...

aired in November 2022 on ABC TV.

Literature

* In his 1944 novel '' The North Wind of Love'' (Bk.1), Compton Mackenzie adumbrates the liberation of the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Cathedral and its return to Scotland by a group of Scottish Nationalists. However, the plan was aborted after one of the protagonists in his cups told a journalist about it, the journalist promptly arranging for the plot to be published in the daily press. It seems likely that this fictional plot to remove the Stone was the inspiration for its actual removal in 1950. *Andrew Greig

Andrew Greig (born 23 September 1951) is a Scottish writer. He was born in Bannockburn, near Stirling, and grew up in Anstruther, Fife. He studied philosophy at the University of Edinburgh and is a former Glasgow University Writing Fellow and S ...

's 2008 novel ''Romanno Bridge

''Romanno Bridge'' is the sixth novel by Scottish writer Andrew Greig.

Plot summary

The book is a sequel to Greig's second novel, '' The Return of John MacNab''. It reunites the main characters from the previous book, and teams them with a ha ...

'' is about a quest for the real Stone of Scone.

* August Derleth

August William Derleth (February 24, 1909 – July 4, 1971) was an American writer and anthologist. Though best remembered as the first book publisher of the writings of H. P. Lovecraft, and for his own contributions to the Cthulhu Mythos and the ...

featured the removal and return of the stone in his short story " The Adventure of the Stone of Scone".

*In the alternate history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, altern ...

novel ''Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

'' by C. J. Sansom, the Stone of Scone is returned to Scotland by the fictional Nazi puppet government in control of the United Kingdom during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

*In ''The Fifth Elephant

''The Fifth Elephant'' is a fantasy novel by British writer Terry Pratchett, the 24th book in the ''Discworld'' series. It introduces the clacks, a long-distance semaphore system.

Plot summary

The Ankh-Morpork City Watch is expanding; there i ...

'', by Terry Pratchett

Sir Terence David John Pratchett (28 April 1948 – 12 March 2015) was an English humourist, satirist, and author of fantasy novels, especially comical works. He is best known for his ''Discworld'' series of 41 novels.

Pratchett's first nov ...

, the Scone of Stone sed for the coronation of Dwarven kingsis destroyed and duplicated.

See also

*Blarney Stone

The Blarney Stone ( ga, Cloch na Blarnan) is a block of Carboniferous limestone built into the battlements of Blarney Castle, Blarney, about from Cork, Ireland. According to legend, kissing the stone endows the kisser with ''the gift of the g ...

(Ireland)

* Coronation Stone, Kingston upon Thames (England)

* Duke's Chair

The Duke's Chair, also known as the Duke's Seat (german: Herzogstuhl, sl, vojvodski prestol or ), is a medieval stone seat dating from the ninth century and located at the Zollfeld plain near Maria Saal, north of Klagenfurt in the Austrian state ...

(Austria)

* Edward Faraday Odlum

* History of Scotland

The recorded begins with the arrival of the Roman Empire in the 1st century, when the province of Britannia reached as far north as the Antonine Wall. North of this was Caledonia, inhabited by the ''Picti'', whose uprisings forced Rom ...

* Lia Fáil

The (; meaning "Stone of Destiny" or "Speaking Stone" to account for its oracular legend) is a stone at the Inauguration Mound ( ga, an Forrad) on the Hill of Tara in County Meath, Ireland, which served as the coronation stone for the High K ...

(Ireland)

* Omphalos

* Prince's Stone (Slovenia)

* Stone of Jacob

The Stone of Jacob appears in the Book of Genesis as the stone used as a pillow by the Israelite patriarch Jacob at the place later called Bet-El. As Jacob had a vision in his sleep, he then consecrated the stone to God. More recently, the stone ...

* Stones of Mora

The Stones of Mora () is a historic location in Knivsta, Sweden. Several Medieval kings of Sweden were proclaimed at

the assembly of Mora near modern Uppsala. It was moved in the 15th century and was considered to have been lost. However, ther ...

(Sweden)

References

Further reading

* ''No Stone Unturned: The Story of the Stone of Destiny'', Ian R. Hamilton, Victor Gollancz and also Funk and Wagnalls, 1952, 1953, hardcover, 191 pages, An account of the return of the stone to Scotland in 1950 (older, but more available) * ''Taking of the Stone of Destiny'', Ian R. Hamilton, Seven Hills Book Distributors, 1992, hardcover, (modern reprint, but expensive) * Martin-Gil F.J., Martin-Ramos P. and Martin-Gil J. "Is Scotland's Coronation Stone a Measurement Standard from the Middle Bronze Age?". ''Anistoriton'', issue P024 of 14 December 2002. * ''The Stone of Destiny: Symbol of Nationhood'' by David Breeze, Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments, and Graeme Munro, Chief Executive, Historic Scotland; Published by ''Historic Scotland

Historic Scotland ( gd, Alba Aosmhor) was an executive agency of the Scottish Office and later the Scottish Government from 1991 to 2015, responsible for safeguarding Scotland's built heritage, and promoting its understanding and enjoyment. ...

'' 1997:

External links

*Highlights: The Stone of Destiny

Edinburgh Castle website

sacred kingship in the 21st century {{DEFAULTSORT:Stone Of Scone Individual thrones

Scone

A scone is a baked good, usually made of either wheat or oatmeal with baking powder as a leavening agent, and baked on sheet pans. A scone is often slightly sweetened and occasionally glazed with egg wash. The scone is a basic component ...

Scottish royalty

British monarchy

Art and cultural repatriation

Sacred rocks