Steller's sea cow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Steller's sea cow (''Hydrodamalis gigas'') is an extinct

Steller's sea cows are reported to have grown to long as adults, much larger than extant

Steller's sea cows are reported to have grown to long as adults, much larger than extant  As with all sirenians, the sea cow's snout pointed downwards, which allowed it to better grasp

As with all sirenians, the sea cow's snout pointed downwards, which allowed it to better grasp

Whether Steller's sea cow had any natural

Whether Steller's sea cow had any natural  Steller described the sea cow as being highly social (

Steller described the sea cow as being highly social (

For decades after its discovery, no skeletal remains of a Steller's sea cow were known. This may have been due to rising and falling sea levels over the course of the Quaternary period, which could have left many sea cow bones hidden. The first bones of a Steller's sea cow were unearthed in about 1840, over 70 years after it was presumed to have become extinct. The first partial sea cow skull was discovered in 1844 by

For decades after its discovery, no skeletal remains of a Steller's sea cow were known. This may have been due to rising and falling sea levels over the course of the Quaternary period, which could have left many sea cow bones hidden. The first bones of a Steller's sea cow were unearthed in about 1840, over 70 years after it was presumed to have become extinct. The first partial sea cow skull was discovered in 1844 by

The range of Steller's sea cow at the time of its discovery was apparently restricted to the shallow seas around the

The range of Steller's sea cow at the time of its discovery was apparently restricted to the shallow seas around the

The presence of Steller's sea cows in the Aleutian Islands may have caused the Aleut people to migrate westward to hunt them. This possibly led to the sea cow's extirpation in that area, assuming it had not already happened yet, but the archaeological evidence is inconclusive. One factor potentially leading to extinction of Steller's sea cow, specifically off the coast of St. Lawrence Island, was the Siberian Yupik people who have inhabited St. Lawrence island for 2,000 years. They may have hunted the sea cows into extinction, as the natives have a dietary culture heavily dependent upon

The presence of Steller's sea cows in the Aleutian Islands may have caused the Aleut people to migrate westward to hunt them. This possibly led to the sea cow's extirpation in that area, assuming it had not already happened yet, but the archaeological evidence is inconclusive. One factor potentially leading to extinction of Steller's sea cow, specifically off the coast of St. Lawrence Island, was the Siberian Yupik people who have inhabited St. Lawrence island for 2,000 years. They may have hunted the sea cows into extinction, as the natives have a dietary culture heavily dependent upon

In the story ''The White Seal'' from ''

In the story ''The White Seal'' from ''

Animal Diversity Web

Steller's sea cow information from the BBC

{{Authority control Extinct mammals of North America Extinct mammals of Asia Species made extinct by human activities Pleistocene sirenians Mammal extinctions since 1500 Sirenians Mammals described in 1780 Taxa named by Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann Commander Islands Extinct animals of Russia Extinct animals of the United States

sirenia

The Sirenia (), commonly referred to as sea-cows or sirenians, are an order of fully aquatic, herbivorous mammals that inhabit swamps, rivers, estuaries, marine wetlands, and coastal marine waters. The Sirenia currently comprise two distinct ...

n described by Georg Wilhelm Steller

Georg Wilhelm Steller (10 March 1709 – 14 November 1746) was a German botanist, zoologist, physician and explorer, who worked in Russia and is considered a pioneer of Alaskan natural history.Evans, Howard Ensign. Edward Osborne Wilson (col.) ...

in 1741. At that time, it was found only around the Commander Islands

The Commander Islands, Komandorski Islands, or Komandorskie Islands (russian: Командо́рские острова́, ''Komandorskiye ostrova'') are a series of treeless, sparsely populated Russian islands in the Bering Sea located about ea ...

in the Bering Sea between Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

; its range extended across the North Pacific during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided by ...

, and likely contracted to such an extreme degree due to the glacial cycle. It is possible indigenous populations interacted with the animal before Europeans. Steller first encountered it on Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering (baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering, was a Danish cartographer and explorer in ...

's Great Northern Expedition

The Great Northern Expedition (russian: Великая Северная экспедиция) or Second Kamchatka Expedition (russian: Вторая Камчатская экспедиция) was one of the largest exploration enterprises in hi ...

when the crew became shipwrecked on Bering Island

Bering Island (russian: о́стров Бе́ринга, ''ostrov Beringa'') is located off the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Bering Sea.

Description

At long by wide, it is the largest and westernmost of the Commander Islands, with an area of . ...

. Much of what is known about its behavior comes from Steller's observations on the island, documented in his posthumous publication ''On the Beasts of the Sea''. Within 27 years of its discovery by Europeans, the slow-moving and easily-caught mammal was hunted into extinction for its meat, fat, and hide.

Some 18th-century adults would have reached weights of and lengths up to . It was a member of the family Dugongidae

Dugongidae is a family in the order of Sirenia. The family has one surviving species, the dugong (''Dugong dugon''), one recently extinct species, Steller's sea cow (''Hydrodamalis gigas''), and a number of extinct genera known from fossil r ...

, of which the long dugong

The dugong (; ''Dugong dugon'') is a marine mammal. It is one of four living species of the order Sirenia, which also includes three species of manatees. It is the only living representative of the once-diverse family Dugongidae; its closest m ...

(''Dugong dugon'') is the sole living member. It had a thicker layer of blubber than other members of the order, an adaptation to the cold waters of its environment. Its tail was forked, like that of whales or dugongs. Lacking true teeth, it had an array of white bristles on its upper lip and two keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, ho ...

ous plates within its mouth for chewing. It fed mainly on kelp

Kelps are large brown algae seaweeds that make up the order Laminariales. There are about 30 different genera. Despite its appearance, kelp is not a plant - it is a heterokont, a completely unrelated group of organisms.

Kelp grows in "underwa ...

, and communicated with sighs and snorting sounds. Steller believed it was a monogamous and social animal living in small family groups and raising its young, similar to modern sirenians.

Description

Steller's sea cows are reported to have grown to long as adults, much larger than extant

Steller's sea cows are reported to have grown to long as adults, much larger than extant sirenia

The Sirenia (), commonly referred to as sea-cows or sirenians, are an order of fully aquatic, herbivorous mammals that inhabit swamps, rivers, estuaries, marine wetlands, and coastal marine waters. The Sirenia currently comprise two distinct ...

ns. In 1987, a rather complete skeleton was found on Bering Island measuring . In 2017, another such skeleton was found on Bering Island measuring , and in life probably about . Georg Steller's writings contain two contradictory estimates of weight: . The true value is estimated to fall between these figures, at about . This size made the sea cow one of the largest mammals of the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided by ...

, along with whales, and was likely an adaptation to reduce its surface-area to volume ratio and conserve heat.

Unlike other sirenians, Steller's sea cow was positively buoyant

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the pr ...

, meaning that it was unable to submerge completely. It had a very thick outer skin, , to prevent injury from sharp rocks and ice and possibly to prevent unsubmerged skin from drying out. The sea cow's blubber was thick, another adaptation to the frigid climate of the Bering Sea. Its skin was brownish-black, with white patches on some individuals. It was smooth along its back and rough on its sides, with crater-like depressions most likely caused by parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s. This rough texture led to the animal being nicknamed the "bark animal". Hair on its body was sparse, but the insides of the sea cow's flippers were covered in bristles. The fore limbs were roughly long, and the tail fluke was forked.

The sea cow's head was small and short in comparison to its huge body. The animal's upper lip was large and broad, extending so far beyond the lower jaw

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

that the mouth appeared to be located underneath the skull. Unlike other sirenians, Steller's sea cow was toothless and instead had a dense array of interlacing white bristles on its upper lip. The bristles were about in length and were used to tear seaweed stalks and hold food. The sea cow also had two keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, ho ...

ous plates, called ceratodontes, located on its palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly separ ...

and mandible

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

, used for chewing. According to Steller, these plates (or "masticatory pads") were held together by interdental papilla

The interdental papilla, also known as the interdental gingiva, is the part of the gums (gingiva) that exists coronal to the free gingival margin on the buccal and lingual surfaces of the teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified struc ...

e, a part of the gums

The gums or gingiva (plural: ''gingivae'') consist of the mucosal tissue that lies over the mandible and maxilla inside the mouth. Gum health and disease can have an effect on general health.

Structure

The gums are part of the soft tissue lin ...

, and had many small holes containing nerves and arteries

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pu ...

.

As with all sirenians, the sea cow's snout pointed downwards, which allowed it to better grasp

As with all sirenians, the sea cow's snout pointed downwards, which allowed it to better grasp kelp

Kelps are large brown algae seaweeds that make up the order Laminariales. There are about 30 different genera. Despite its appearance, kelp is not a plant - it is a heterokont, a completely unrelated group of organisms.

Kelp grows in "underwa ...

. The sea cow's nostrils were roughly long and wide. In addition to those within its mouth, the sea cow also had stiff bristles long protruding from its muzzle. Steller's sea cow had small eyes located halfway between its nostrils and ears with black irises, livid

LiViD, short for Linux Video and DVD, was a collection of projects that aim to create program tools and software libraries related to DVD for Linux operating system.

The projects included:

* OMS

* GATOS

* mpeg2dec

* ac3dec

In 2002, LiViD project ...

eyeballs, and canthi

The canthus (pl. canthi, palpebral commissures) is either corner of the eye where the upper and lower eyelids meet. More specifically, the inner and outer canthi are, respectively, the medial and lateral ends/angles of the palpebral fissure.

T ...

which were not externally visible. The animal had no eyelashes, but like other diving creatures such as sea otters, Steller's sea cow had a nictitating membrane, which covered its eyes to prevent injury while feeding. The tongue was small and remained in the back of the mouth, unable to reach the masticatory (chewing) pads.

The sea cow's spine is believed to have had seven cervical

In anatomy, cervical is an adjective that has two meanings:

# of or pertaining to any neck.

# of or pertaining to the female cervix: i.e., the ''neck'' of the uterus.

*Commonly used medical phrases involving the neck are

**cervical collar

**cerv ...

(neck), 17 thoracic

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the crea ...

, three lumbar, and 34 caudal (tail) vertebrae. Its ribs were large, with five of 17 pairs making contact with the sternum

The sternum or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels from injury. Sha ...

; it had no clavicle

The clavicle, or collarbone, is a slender, S-shaped long bone approximately 6 inches (15 cm) long that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and the sternum (breastbone). There are two clavicles, one on the left and one on the r ...

s. As in all sirenians, the scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

of Steller's sea cow was fan-shaped, being larger on the posterior side and narrower towards the neck. The anterior border of the scapula was nearly straight, whereas those of modern sirenians are curved. Like other sirenians, the bones of Steller's sea cow were pachyosteosclerotic, meaning they were both bulky ( pachyostotic) and dense ( osteosclerotic). In all collected skeletons of the sea cow, the manus is missing; since ''Dusisiren

''Dusisiren'' is an extinct genus of dugong related to the Steller's sea cow that lived in the North Pacific during the Neogene.

Paleobiology

''Dusisiren'' is a sirenian exemplar of the evolutionary theory of punctuated equilibrium. It evolved ...

''—the sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

of ''Hydrodamalis

''Hydrodamalis'' is a genus of extinct herbivorous sirenian marine mammals, and included the Steller's sea cow (''Hydrodamalis gigas''), the Cuesta sea cow (''Hydrodamalis cuestae''), and the Takikawa sea cow (''Hydrodamalis spissa''). The fossi ...

''—had reduced phalanges (finger bones), Steller's sea cow possibly did not have a manus at all.

The sea cow's heart was in weight; its stomach measured long and wide. The full length of its intestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

was about , equaling more than 20 times the animal's length. The sea cow had no gallbladder

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although ...

, but did have a wide common bile duct

The common bile duct, sometimes abbreviated as CBD, is a duct in the gastrointestinal tract of organisms that have a gallbladder. It is formed by the confluence of the common hepatic duct and cystic duct and terminates by uniting with pancrea ...

. Its anus was in width, with its feces resembling those of horses. The male's penis was long. Genetic evidence indicates convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

with other marine mammals of genes related to metabolic and immune function, including leptin associated with energy homeostasis

In biology, homeostasis (British also homoeostasis) (/hɒmɪə(ʊ)ˈsteɪsɪs/) is the state of steady internal, physical, and chemical conditions maintained by living systems. This is the condition of optimal functioning for the organism and ...

and reproductive regulation.

Ecology and behavior

Whether Steller's sea cow had any natural

Whether Steller's sea cow had any natural predators

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

is unknown. It may have been hunted by killer whale

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white ...

s and shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s, though its buoyancy may have made it difficult for killer whales to drown, and the rocky kelp forest

Kelp forests are underwater areas with a high density of kelp, which covers a large part of the world's coastlines. Smaller areas of anchored kelp are called kelp beds. They are recognized as one of the most productive and dynamic ecosystems on Ea ...

s in which the sea cow lived may have deterred sharks. According to Steller, the adults guarded the young from predators.

Steller described an ectoparasite on the sea cows that was similar to the whale louse

A whale louse is a commensal crustacean of the family Cyamidae. Despite the name, it is not a true louse (which are insects), but rather is related to the skeleton shrimp, most species of which are found in shallower waters. Whale lice are exter ...

(''Cyamus ovalis''), but the parasite remains unidentified due to the host's extinction and loss of all original specimens collected by Steller. It was first formally described as ''Sirenocyamus rhytinae'' in 1846 by Johann Friedrich von Brandt, although it has since been placed into the genus '' Cyamus'' as '' Cyamus rhytinae''. It was the only species of cyamid amphipod to be reported inhabiting a sirenian. Steller also identified an endoparasite in the sea cows, which was likely an ascarid nematode.

Like other sirenians, Steller's sea cow was an obligate herbivore and spent most of the day feeding, only lifting its head every 4–5 minutes for breathing. Kelp was its main food source, making it an algivore

Algae eater or algivore is a common name for any bottom-dwelling or filter-feeding aquatic animal species that specialize in feeding on algae and phytoplanktons. Algae eaters are important for the fishkeeping hobby and many are commonly kept b ...

. The sea cow likely fed on several species of kelp, which have been identified as '' Agarum'' spp., '' Alaria praelonga'', '' Halosaccion glandiforme'', '' Laminaria saccharina'', '' Nereocyctis luetkeana'', and '' Thalassiophyllum clathrus''. Steller's sea cow only fed directly on the soft parts of the kelp, which caused the tougher stem and holdfast to wash up on the shore in heaps. The sea cow may have also fed on seagrass

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants which grow in marine environments. There are about 60 species of fully marine seagrasses which belong to four families (Posidoniaceae, Zosteraceae, Hydrocharitaceae and Cymodoceaceae), all in the or ...

, but the plant was not common enough to support a viable population and could not have been the sea cow's primary food source. Further, the available seagrasses in the sea cow's range ('' Phyllospadix'' spp. and ''Zostera marina

''Zostera marina'' is a flowering vascular plant species as one of many kinds of seagrass, with this species known primarily by the English name of eelgrass with seawrack much less used, and refers to the plant after breaking loose from the submer ...

'') may have grown too deep underwater or been too tough for the animal to consume. Since the sea cow floated, it likely fed on canopy

Canopy may refer to:

Plants

* Canopy (biology), aboveground portion of plant community or crop (including forests)

* Canopy (grape), aboveground portion of grapes

Religion and ceremonies

* Baldachin or canopy of state, typically placed over an ...

kelp, as it is believed to have only had access to food no deeper than below the tide. Kelp releases a chemical deterrent to protect it from grazing, but canopy kelp releases a lower concentration of the chemical, allowing the sea cow to graze safely. Steller noted that the sea cow grew thin during the frigid winters, indicating a period of fasting

Fasting is the abstention from eating and sometimes drinking. From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see " Breakfast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after ...

due to low kelp growth. Fossils of Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

Aleutian Island

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a chain of 14 large vo ...

sea cow populations were larger than those from the Commander Islands, indicating that the growth of Commander Island sea cows may have been stunted

Stunted growth is a reduced growth rate in human development. It is a primary manifestation of malnutrition (or more precisely undernutrition) and recurrent infections, such as diarrhea and helminthiasis, in early childhood and even before birth, ...

due to a less favorable habitat and less food than the warmer Aleutian Islands.

Steller described the sea cow as being highly social (

Steller described the sea cow as being highly social (gregarious

Sociality is the degree to which individuals in an animal population tend to associate in social groups (gregariousness) and form cooperative societies.

Sociality is a survival response to evolutionary pressures. For example, when a mother wasp ...

). It lived in small family groups and helped injured members, and was also apparently monogamous. Steller's sea cow may have exhibited parental care

Parental care is a behavioural and evolutionary strategy adopted by some animals, involving a parental investment being made to the evolutionary fitness of offspring. Patterns of parental care are widespread and highly diverse across the animal ki ...

, and the young were kept at the front of the herd for protection against predators. Steller reported that as a female was being captured, a group of other sea cows attacked the hunting boat by ramming and rocking it, and after the hunt, her mate followed the boat to shore, even after the captured animal had died. Mating season occurred in early spring and gestation took a little over a year, with calves likely delivered in autumn, as Steller observed a greater number of calves in autumn than at any other time of the year. Since female sea cows had only one set of mammary gland

A mammary gland is an exocrine gland in humans and other mammals that produces milk to feed young offspring. Mammals get their name from the Latin word ''mamma'', "breast". The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in pri ...

s, they likely had one calf at a time.

The sea cow used its fore limbs for swimming, feeding, walking in shallow water, defending itself, and holding on to its partner during copulation. According to Steller, the fore limbs were also used to anchor the sea cow down to prevent it from being swept away by the strong nearshore waves. While grazing, the sea cow progressed slowly by moving its tail (fluke) from side to side; more rapid movement was achieved by strong vertical beating of the tail. They often slept on their backs after feeding. According to Steller, the sea cow was nearly mute and made only heavy breathing sounds, raspy snorting similar to a horse, and sighs.

Despite their large size, as with many other marine megafauna in the region, Steller's sea cows may have been prey for the local transient orcas (''Orcinus orca''); it is likely that they experienced predation, as Steller observed that foraging sea cows with calves would always keep their calves between themselves and the shore, and orcas would have been the most likely candidate for causing this behavior. In addition, early indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

of the North Pacific may have depended on the sea cow for food, and it is possible that this dependency may have extirpated

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...

the sea cow from portions of the North Pacific aside from the Commander Islands. Steller's sea cows may have also had a mutualistic (or possibly even parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

) relationship with local seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

species; Steller often observed birds perching on the exposed backs of the sea cows, feeding on the parasitic ''Cyamus rhytinae''; this unique relationship that disappeared with the sea cows may have been a food source for many birds, and is similar to the recorded interactions between oxpecker

The oxpeckers are two species of bird which make up the genus ''Buphagus'', and family Buphagidae. The oxpeckers were formerly usually treated as a subfamily, Buphaginae, within the starling family, Sturnidae, but molecular phylogenetic studi ...

s (''Buphagus'') and extant African megafauna.

Taxonomy

Phylogeny

Steller's sea cow was a member of thegenus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

''Hydrodamalis

''Hydrodamalis'' is a genus of extinct herbivorous sirenian marine mammals, and included the Steller's sea cow (''Hydrodamalis gigas''), the Cuesta sea cow (''Hydrodamalis cuestae''), and the Takikawa sea cow (''Hydrodamalis spissa''). The fossi ...

'', a group of large sirenians, whose sister taxon was ''Dusisiren

''Dusisiren'' is an extinct genus of dugong related to the Steller's sea cow that lived in the North Pacific during the Neogene.

Paleobiology

''Dusisiren'' is a sirenian exemplar of the evolutionary theory of punctuated equilibrium. It evolved ...

''. Like those of Steller's sea cow, the ancestors of ''Dusisiren'' lived in tropical mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evolution in severa ...

s before adapting to the cold climates of the North Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. ''Hydrodamalis'' and ''Dusisiren'' are classified together in the subfamily Hydrodamalinae

Hydrodamalinae is a recently extinct subfamily of the sirenian family Dugongidae. The Steller's sea cow (''Hydrodamalis gigas'') was hunted to extinction by 1768, while the genus '' Dusisiren'' is known from fossils dating from the middle Miocen ...

, which diverged from other sirenians around 4 to 8 mya. Steller's sea cow is a member of the family Dugongidae

Dugongidae is a family in the order of Sirenia. The family has one surviving species, the dugong (''Dugong dugon''), one recently extinct species, Steller's sea cow (''Hydrodamalis gigas''), and a number of extinct genera known from fossil r ...

, the sole surviving member of which, and thus Steller's sea cow's closest living relative, is the dugong

The dugong (; ''Dugong dugon'') is a marine mammal. It is one of four living species of the order Sirenia, which also includes three species of manatees. It is the only living representative of the once-diverse family Dugongidae; its closest m ...

(''Dugong dugon'').

Steller's sea cow was a direct descendant of the Cuesta sea cow

The Cuesta sea cow (''Hydrodamalis cuestae'') is an extinct herbivorous marine mammal and is the direct ancestor of the Steller's sea cow (''Hydrodamalis gigas''). They reached up to in length, making them among the biggest sirenians to have eve ...

(''H. cuestae''), an extinct tropical sea cow that lived off the coast of western North America, particularly California. The Cuesta sea cow is thought to have become extinct due to the onset of the Quaternary glaciation

The Quaternary glaciation, also known as the Pleistocene glaciation, is an alternating series of glacial and interglacial periods during the Quaternary period that began 2.58 Ma (million years ago) and is ongoing. Although geologists describ ...

and the subsequent cooling of the oceans. Many populations died out, but the lineage of Steller's sea cow was able to adapt to the colder temperatures. The Takikawa sea cow (''H. spissa'') of Japan is thought of by some researchers to be a taxonomic synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Lin ...

of the Cuesta sea cow, but based on a comparison of endocast

An endocast is the internal cast of a hollow object, often referring to the cranial vault in the study of brain development in humans and other organisms. Endocasts can be artificially made for examining the properties of a hollow, inaccessible sp ...

s, the Takikawa and Steller's sea cows are more derived than the Cuesta sea cow. This has led some to believe that the Takikawa sea cow is its own species. The evolution of the genus ''Hydrodamalis'' was characterized by increased size, and a loss of teeth and phalanges, as a response to the onset of the Quaternary glaciation.

Research history

Steller's sea cow was discovered in 1741 by Georg Wilhelm Steller, and was named after him. Steller researched the wildlife ofBering Island

Bering Island (russian: о́стров Бе́ринга, ''ostrov Beringa'') is located off the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Bering Sea.

Description

At long by wide, it is the largest and westernmost of the Commander Islands, with an area of . ...

while he was shipwrecked there for about a year; the animals on the island included relict

A relict is a surviving remnant of a natural phenomenon.

Biology

A relict (or relic) is an organism that at an earlier time was abundant in a large area but now occurs at only one or a few small areas.

Geology and geomorphology

In geology, a r ...

populations of sea cows, sea otters, Steller sea lions, and northern fur seal

The northern fur seal (''Callorhinus ursinus'') is an eared seal found along the north Pacific Ocean, the Bering Sea, and the Sea of Okhotsk. It is the largest member of the fur seal subfamily (Arctocephalinae) and the only living species in t ...

s. As the crew hunted the animals to survive, Steller described them in detail. Steller's account was included in his posthumous publication ''De bestiis marinis'', or ''The Beasts of the Sea'', which was published in 1751 by the Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across ...

in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. Zoologist Eberhard von Zimmermann formally described Steller's sea cow in 1780 as ''Manati gigas''. Biologist Anders Jahan Retzius

Anders Jahan Retzius (3 October 1742 – 6 October 1821) was a Swedish chemist, botanist and entomologist.

Biography

Born in Kristianstad, he matriculated at Lund University in 1758, where he graduated as a filosofie magister in 1766. He also ...

in 1794 put the sea cow in the new genus ''Hydrodamalis'', with the specific name of ''stelleri'', in honor of Steller. In 1811, naturalist Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger

Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger (19 November 1775 – 10 May 1813) was a German entomologist and zoologist.

Illiger was the son of a merchant in Braunschweig. He studied under the entomologist Johann Hellwig, and later worked on the zoological colle ...

reclassified Steller's sea cow into the genus ''Rytina'', which many writers at the time adopted. The name ''Hydrodamalis gigas'', the correct '' combinatio nova'' if a separate genus is recognised, was first used in 1895 by Theodore Sherman Palmer

Theodore Sherman Palmer (January 26, 1868 – July 24, 1955) was an American zoologist.

Palmer was born in Oakland, California, and studied at the University of California. He was the son of Henry Austin and Jane Olivia (Day) Palmer, and his m ...

.

For decades after its discovery, no skeletal remains of a Steller's sea cow were known. This may have been due to rising and falling sea levels over the course of the Quaternary period, which could have left many sea cow bones hidden. The first bones of a Steller's sea cow were unearthed in about 1840, over 70 years after it was presumed to have become extinct. The first partial sea cow skull was discovered in 1844 by

For decades after its discovery, no skeletal remains of a Steller's sea cow were known. This may have been due to rising and falling sea levels over the course of the Quaternary period, which could have left many sea cow bones hidden. The first bones of a Steller's sea cow were unearthed in about 1840, over 70 years after it was presumed to have become extinct. The first partial sea cow skull was discovered in 1844 by Ilya Voznesensky

Ilya Gavrilovich Voznesensky (russian: Илья́ Гаври́лович Вознесе́нский, also romanized as Ilia or Il'ia Voznesenskii or Wosnesenski, June 19, 1816 – May 18, 1871) was a Russian explorer and naturalist associated with ...

while on the Commander Islands, and the first skeleton was discovered in 1855 on northern Bering Island. These specimens were sent to Saint Petersburg in 1857, and another nearly complete skeleton arrived in Moscow around 1860. Until recently, all the full skeletons were found during the 19th century, being the most productive period in terms of unearthed skeletal remains, from 1878 to 1883. During this time, 12 of the 22 skeletons having known dates of collection were discovered. Some authors did not believe possible the recovery of further significant skeletal material from the Commander Islands after this period, but a skeleton was found in 1983, and two zoologists collected about 90 bones in 1991. Only two to four skeletons of the sea cow exhibited in various museums of the world originate from a single individual. It is known that Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld

Nils Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (18 November 183212 August 1901) was a Finland-Swedish aristocrat, geologist, mineralogist and Arctic explorer. He was a member of the Fenno-Swedish Nordenskiöld family of scientists and held the title of a friher ...

, Benedykt Dybowski

Benedykt Tadeusz Dybowski (12 May 183331 January 1930) was a Polish naturalist and physician.

Life

Benedykt Dybowski was born in Adamaryni, within the Minsk Governorate of the Russian Empire to Polish nobility. He was the brother of naturalis ...

, and Leonhard Hess Stejneger

Leonhard Hess Stejneger (30 October 1851 – 28 February 1943) was a Norwegian-born United States, American ornithologist, herpetologist and zoologist. Stejneger specialized in vertebrate natural history studies. He gained his greatest reputatio ...

unearthed many skeletal remains from different individuals in the late 1800s, from which composite skeletons were assembled. As of 2006, 27 nearly complete skeletons and 62 complete skulls have been found, but most of them are assemblages of bones from two to 16 different individuals.

In 2021, the nuclear genome

Nuclear DNA (nDNA), or nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid, is the DNA contained within each cell nucleus of a eukaryotic organism. It encodes for the majority of the genome in eukaryotes, with mitochondrial DNA and plastid DNA coding for the rest. I ...

was sequenced.

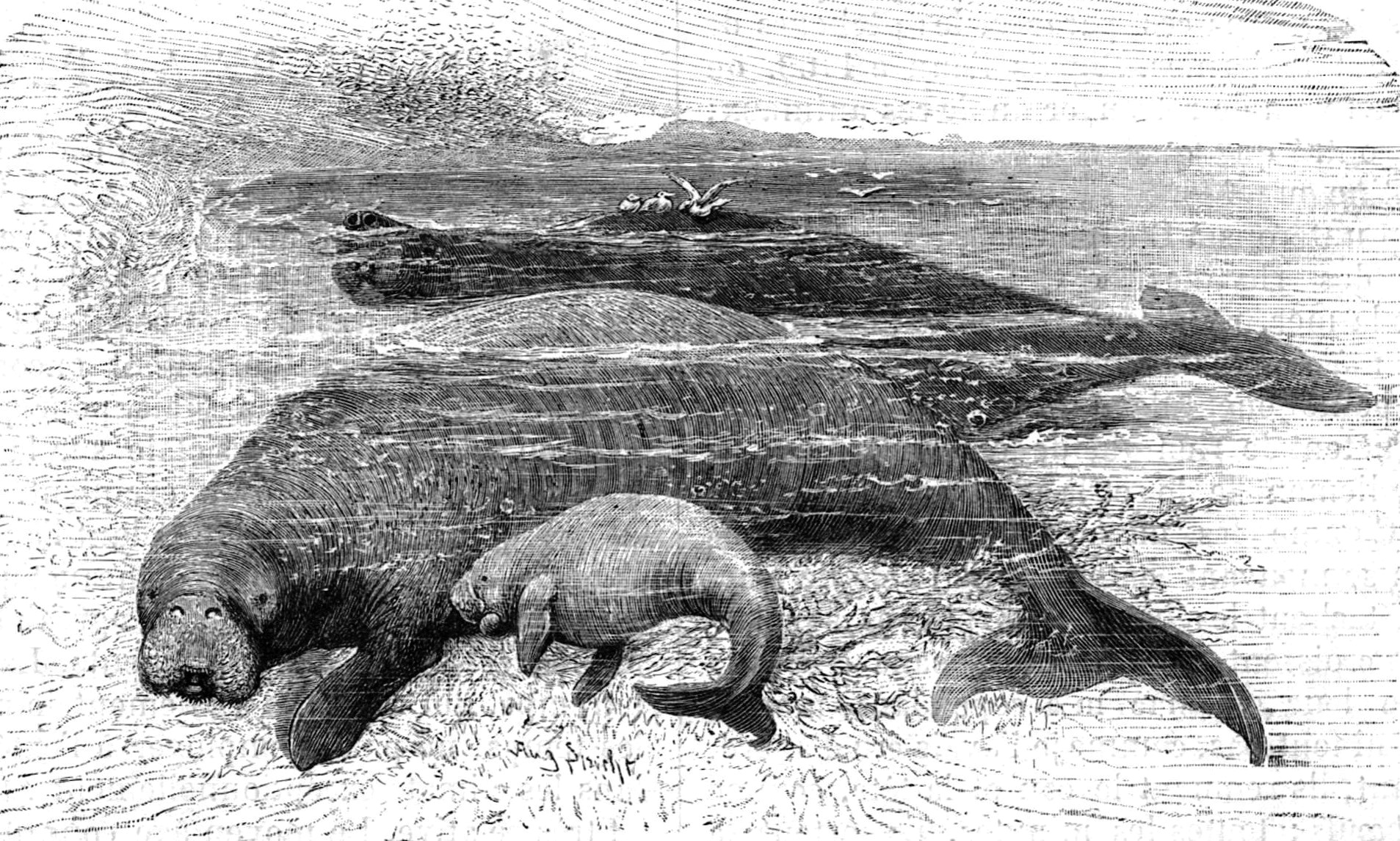

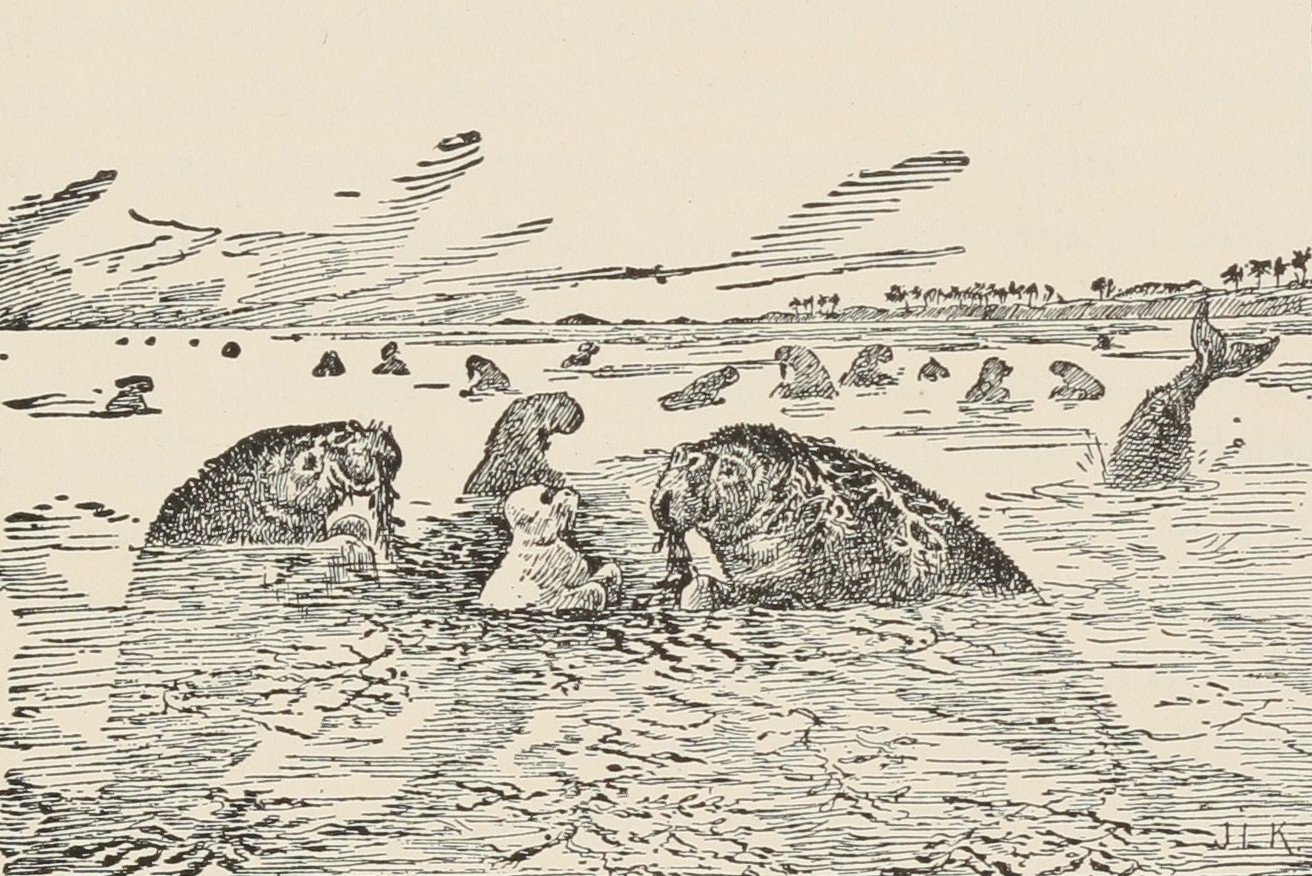

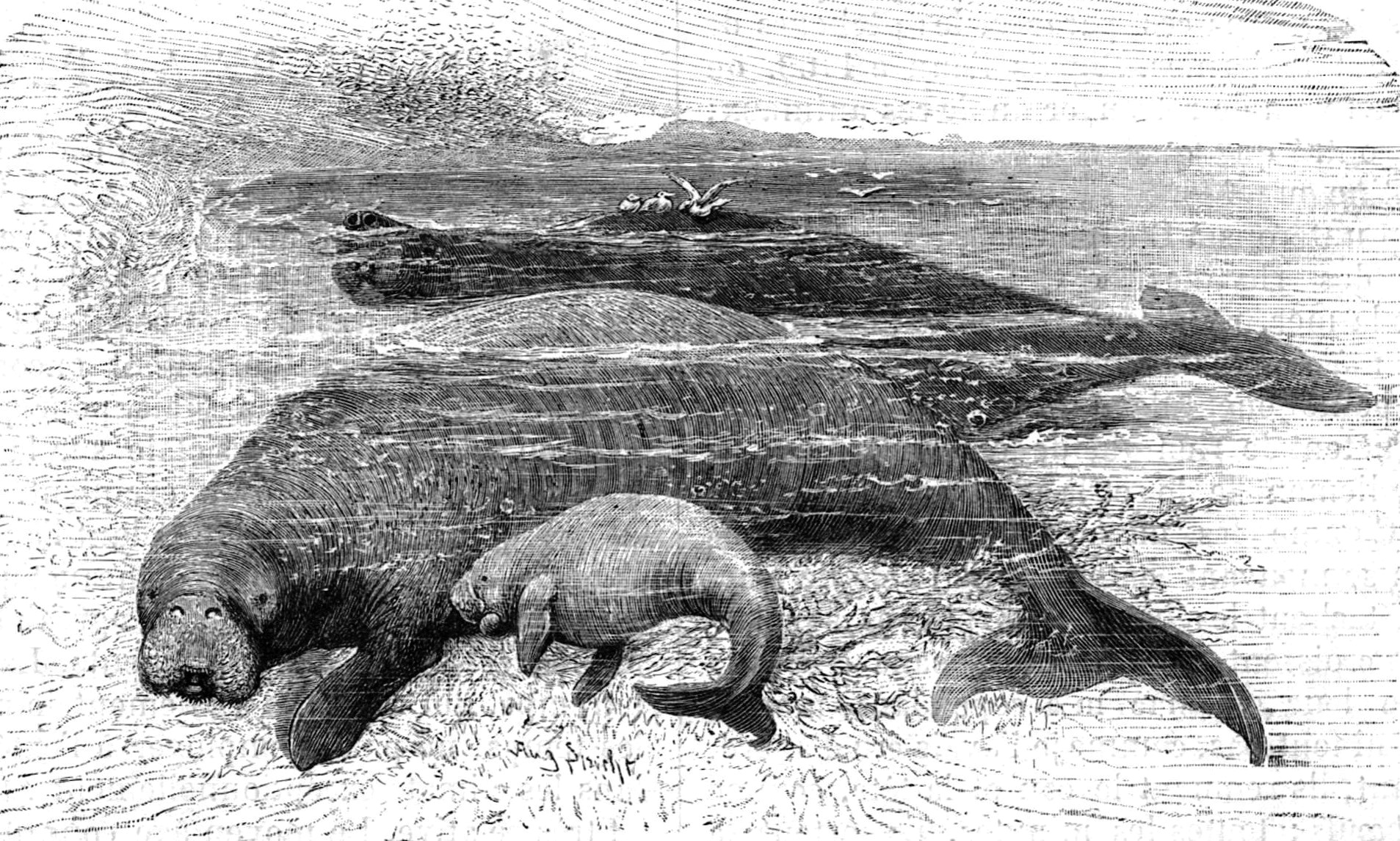

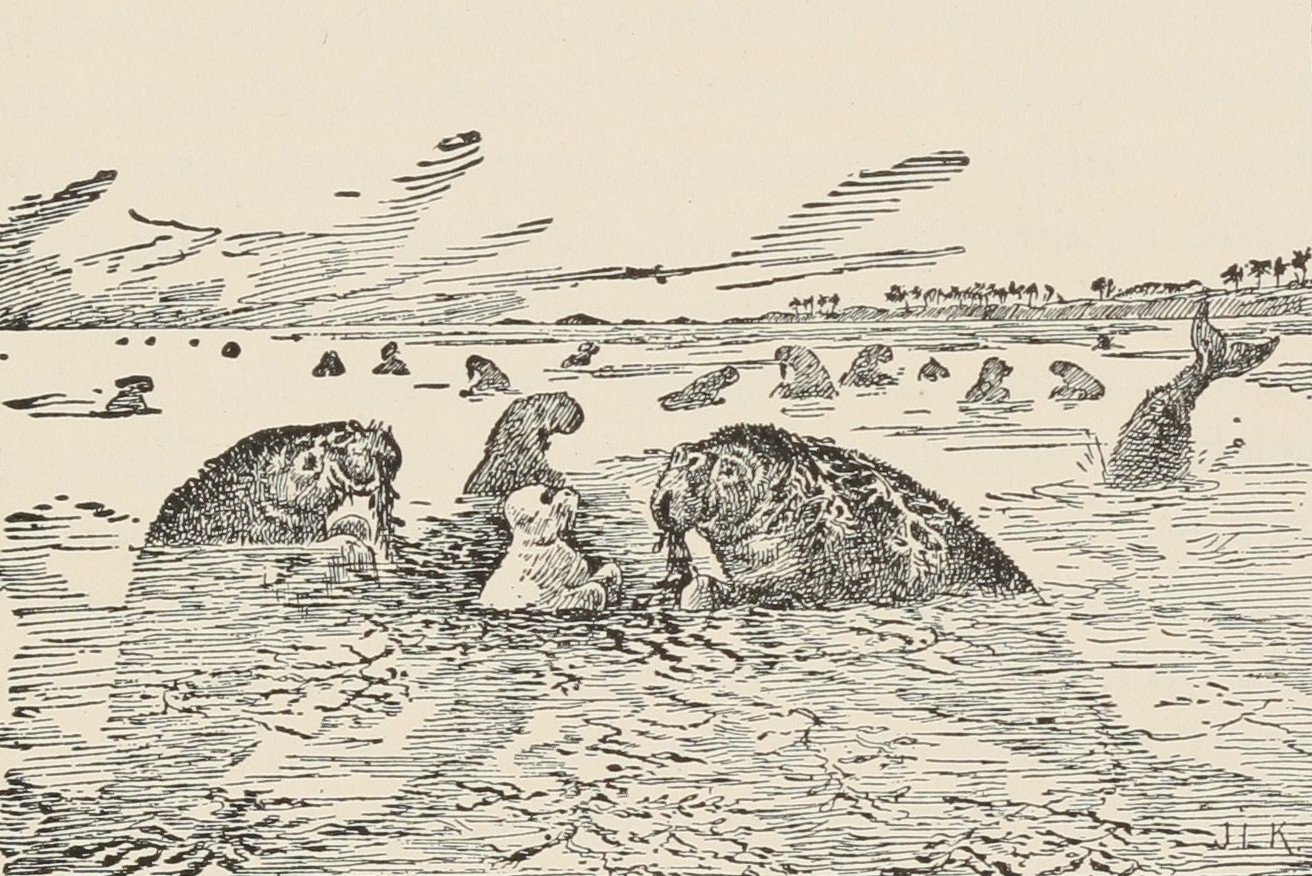

Illustrations

The Pallas Picture is the only known drawing of Steller's sea cow believed to be from a complete specimen. It was published byPeter Simon Pallas

Peter Simon Pallas FRS FRSE (22 September 1741 – 8 September 1811) was a Prussian zoologist and botanist who worked in Russia between 1767 and 1810.

Life and work

Peter Simon Pallas was born in Berlin, the son of Professor of Surgery ...

in his 1840 work ''Icones ad Zoographia Rosso-Asiatica''. Pallas did not specify a source; Stejneger suggested it may have been one of the original illustrations produced by Friedrich Plenisner, a member of Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering (baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering, was a Danish cartographer and explorer in ...

's crew as a painter and surveyor who drew a figure of a female sea cow on Steller's request. Most of Plenisner's depictions were lost during transit from Siberia to Saint Petersburg.

Another drawing of Steller's sea cow similar to the Pallas Picture appeared on a 1744 map drawn by Sven Waxell and Sofron Chitrow. The picture may have also been based upon a specimen, and was published in 1893 by Pekarski. The map depicted Vitus Bering's route during the Great Northern Expedition

The Great Northern Expedition (russian: Великая Северная экспедиция) or Second Kamchatka Expedition (russian: Вторая Камчатская экспедиция) was one of the largest exploration enterprises in hi ...

, and featured illustrations of Steller's sea cow and Steller's sea lion in the upper-left corner. The drawing contains some inaccurate features such as the inclusion of eyelids and fingers, leading to doubt that it was drawn from a specimen.

Johann Friedrich von Brandt, director of the Russian Academy of Sciences, had the "Ideal Image" drawn in 1846 based upon the Pallas Picture, and then the "Ideal Picture" in 1868 based upon collected skeletons. Two other possible drawings of Steller's sea cow were found in 1891 in Waxell's manuscript diary. There was a map depicting a sea cow, as well as a Steller sea lion and a northern fur seal. The sea cow was depicted with large eyes, a large head, claw-like hands, exaggerated folds on the body, and a tail fluke in perspective lying horizontally rather than vertically. The drawing may have been a distorted depiction of a juvenile, as the figure bears a resemblance to a manatee

Manatees (family Trichechidae, genus ''Trichechus'') are large, fully aquatic, mostly herbivorous marine mammals sometimes known as sea cows. There are three accepted living species of Trichechidae, representing three of the four living speci ...

calf. Another similar image was found by Alexander von Middendorff

Alexander Theodor von Middendorff (russian: Алекса́ндр Фёдорович Ми́ддендорф; tr. ; 18 August 1815 – 24 January 1894) was a zoologist and explorer of Baltic German and Estonian extraction. He is known for his ex ...

in 1867 in the library of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and is probably a copy of the Tsarskoye Selo Picture.

Range

The range of Steller's sea cow at the time of its discovery was apparently restricted to the shallow seas around the

The range of Steller's sea cow at the time of its discovery was apparently restricted to the shallow seas around the Commander Islands

The Commander Islands, Komandorski Islands, or Komandorskie Islands (russian: Командо́рские острова́, ''Komandorskiye ostrova'') are a series of treeless, sparsely populated Russian islands in the Bering Sea located about ea ...

, which include Bering and Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

Islands. The Commander Islands remained uninhabited until 1825, when the Russian-American Company

The Russian-American Company Under the High Patronage of His Imperial Majesty (russian: Под высочайшим Его Императорского Величества покровительством Российская-Американс� ...

relocated Aleut

The Aleuts ( ; russian: Алеуты, Aleuty) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleut people and the islands are politically divided between the ...

s from Attu Island and Atka Island

Atka Island ( ale, Atx̂ax̂, russian: Атка остров) is the largest island in the Andreanof Islands of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. The island is east of Adak Island. It is long and wide with a land area of , making it the 22nd l ...

there.

The first fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s discovered outside the Commander Islands were found in interglacial Pleistocene deposits in Amchitka, and further fossils dating to the late Pleistocene were found in Monterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean located on the coast of the U.S. state of California, south of the San Francisco Bay Area and its major city at the south of the bay, San Jose. San Francisco itself is further north along the coast, by ...

, California, and Honshu

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island se ...

, Japan. This suggests that the sea cow had a far more extensive range in prehistoric times. It cannot be excluded that these fossils belong to other ''Hydrodamalis'' species. The southernmost find is a Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. Th ...

rib bone from the Bōsō Peninsula

The is a peninsula that encompasses the entirety of Chiba Prefecture on Honshu, the largest island of Japan. It is part of the Greater Tokyo Area. It forms the eastern edge of Tokyo Bay, separating it from the Pacific Ocean. The peninsula covers ...

of Japan. The remains of three individuals were found preserved in the South Bight Formation of Amchitka; as late Pleistocene interglacial deposits are rare in the Aleutians, the discovery suggests that sea cows were abundant in that era. According to Steller, the sea cow often resided in the shallow, sandy shorelines and in the mouths of freshwater rivers. Genetic evidence suggests Steller's sea cow, as well as the modern dugong, suffered a population bottleneck (a significant reduction in population) bottoming roughly 400,000 years ago.

Bone fragments and accounts by native Aleut people suggest that sea cows also historically inhabited the Near Islands

The Near Islands or Sasignan Islands ( ale, Sasignan tanangin, russian: Ближние острова) are a group of American islands in the Aleutian Islands in southwestern Alaska, between the Russian Commander Islands to the west and the Ra ...

, potentially with viable populations that were in contact with humans in the western Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a chain of 14 large v ...

prior to Steller's discovery in 1741. A sea cow rib discovered in 1998 on Kiska Island

Kiska ( ale, Qisxa, russian: Кыска) is one of the Rat Islands, a group of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. It is about long and varies in width from . It is part of Aleutian Islands Wilderness and as such, special permission is require ...

was dated to around 1,000 years old, and is now in the possession of the Burke Museum

The Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture (Burke Museum) is a natural history museum in Seattle, Washington, in the United States. Established in 1899 as the Washington State Museum, it traces its origins to a high school naturalist club fo ...

in Seattle. The dating may be skewed due to the marine reservoir effect which causes radiocarbon-dated marine specimens to appear several hundred years older than they are. Marine reservoir effect is caused by the large reserves of C14 in the ocean, and it is more likely that the animal died between 1710 and 1785. A 2004 study reported that sea cow bones discovered on Adak Island

Adak Island ( ale, Adaax, russian: Адак) or Father Island is an island near the western extent of the Andreanof Islands group of the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. Alaska's southernmost town, Adak, is located on the island. The island has a lan ...

were around 1,700 years old, and sea cow bones discovered on Buldir Island were found to be around 1,600 years old. It is possible the bones were from cetaceans and were misclassified. Rib bones of a Steller's sea cow have also been found on St. Lawrence Island, and the specimen is thought to have lived between 800 and 920 CE.

Interactions with humans

Extinction

Genetic evidence suggests the Steller's sea cows around the Commander Islands were the last of a much more ubiquitous population dispersed across the North Pacific coastal zones. They had the same genetic diversity as the last and ratherinbred

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely related genetically. By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genetic disorders and o ...

population of woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived during the Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with '' Mammuthus s ...

s on Wrangel Island

Wrangel Island ( rus, О́стров Вра́нгеля, r=Ostrov Vrangelya, p=ˈostrəf ˈvrangʲɪlʲə; ckt, Умӄиԓир, translit=Umqiḷir) is an island of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. It is the 91st largest island in the w ...

. During glacial periods and reduction in sea levels and temperatures, suitable habitat substantially regressed, fragmenting the population. By the time sea levels stabilized around 5,000 years ago, the population had already plummeted. Together, these indicate that even without human influence, the Steller's sea cow would have still been a dead clade walking

In ecology, extinction debt is the future extinction of species due to events in the past. The phrases dead clade walking and survival without recovery express the same idea.

Extinction debt occurs because of time delays between impacts on a speci ...

, with the vast majority of the population having already gone extinct from natural climatic and sea level shifts, with the tiny remaining population at major risk from a genetic extinction vortex.

The presence of Steller's sea cows in the Aleutian Islands may have caused the Aleut people to migrate westward to hunt them. This possibly led to the sea cow's extirpation in that area, assuming it had not already happened yet, but the archaeological evidence is inconclusive. One factor potentially leading to extinction of Steller's sea cow, specifically off the coast of St. Lawrence Island, was the Siberian Yupik people who have inhabited St. Lawrence island for 2,000 years. They may have hunted the sea cows into extinction, as the natives have a dietary culture heavily dependent upon

The presence of Steller's sea cows in the Aleutian Islands may have caused the Aleut people to migrate westward to hunt them. This possibly led to the sea cow's extirpation in that area, assuming it had not already happened yet, but the archaeological evidence is inconclusive. One factor potentially leading to extinction of Steller's sea cow, specifically off the coast of St. Lawrence Island, was the Siberian Yupik people who have inhabited St. Lawrence island for 2,000 years. They may have hunted the sea cows into extinction, as the natives have a dietary culture heavily dependent upon marine mammal

Marine mammals are aquatic mammals that rely on the ocean and other marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as seals, whales, manatees, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their ...

s. The onset of the Medieval Warm Period, which reduced the availability of kelp, may have also been the cause for their local extinction in that area. It has also been argued that the decline of Steller's sea cow may have been an indirect effect of the harvesting of sea otters by the area's aboriginal people. With the otter population reduced, the sea urchin population would have increased, in turn reducing the stock of kelp, its principal food. In historic times, though, aboriginal hunting had depleted sea otter populations only in localized areas, and as the sea cow would have been easy prey for aboriginal hunters, accessible populations may have been exterminated with or without simultaneous otter hunting. In any event, the range of the sea cow was limited to coastal areas off uninhabited islands by the time Bering arrived, and the animal was already endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and in ...

.

When Europeans discovered them, there may have been only 2,000 individuals left. This small population was quickly wiped out by fur traders, seal hunters, and others who followed Vitus Bering's route past its habitat to Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

. It was also hunted to collect its valuable subcutaneous fat

The subcutaneous tissue (), also called the hypodermis, hypoderm (), subcutis, superficial fascia, is the lowermost layer of the integumentary system in vertebrates. The types of cells found in the layer are fibroblasts, adipose cells, and macro ...

. The animal was hunted and used by Ivan Krassilnikov in 1754 and Ivan Korovin 1762, but Dimitri Bragin, in 1772, and others later, did not see it. Brandt thus concluded that by 1768, twenty-seven years after it had been discovered by Europeans, the species was extinct. In 1887, Stejneger estimated that there had been fewer than 1,500 individuals remaining at the time of Steller's discovery, and argued there was already an immediate danger of the sea cow's extinction.

The first attempt to hunt the animal by Steller and the other crew members was unsuccessful due to its strength and thick hide. They had attempted to impale it and haul it to shore using a large hook and heavy cable, but the crew could not pierce its skin. In a second attempt a month later, a harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal ...

er speared an animal, and men on shore hauled it in while others repeatedly stabbed it with bayonets. It was dragged into shallow waters, and the crew waited until the tide receded and it was beached to butcher it. After this, they were hunted with relative ease, the challenge being in hauling the animal back to shore. This bounty inspired maritime fur traders to detour to the Commander Islands and restock their food supplies during North Pacific expeditions.

Impact of extinction

While not a keystone species, Steller's sea cows likely influenced the community composition of thekelp forest

Kelp forests are underwater areas with a high density of kelp, which covers a large part of the world's coastlines. Smaller areas of anchored kelp are called kelp beds. They are recognized as one of the most productive and dynamic ecosystems on Ea ...

s they inhabited, and also boosted their productivity

Productivity is the efficiency of production of goods or services expressed by some measure. Measurements of productivity are often expressed as a ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production proces ...

and resilience to environmental stressors by allowing more light into kelp forests and more kelp to grow, and enhancing the recruitment and dispersal of kelp through their feeding behavior. In the modern day, the flow of nutrients from kelp forests to adjacent ecosystems is regulated by the seasons, with seasonal storms and currents being the primary factor. The Steller's sea cow may have allowed this flow to continue year-round, thus allowing for more productivity in adjacent habitats. The disturbance caused by the Steller's sea cow may have facilitated the dispersal of kelp, most notably '' Nereocystis'' species, to other habitats, allowing recruitment and colonization of new areas, and facilitating genetic exchange. Their presence may have also allowed sea otters and large marine invertebrates

Marine invertebrates are the invertebrates that live in marine habitats. Invertebrate is a blanket term that includes all animals apart from the vertebrate members of the chordate phylum. Invertebrates lack a vertebral column, and some have ev ...

to coexist, indicating a commonly-documented decline in marine invertebrate populations driven by sea otters (an example being in populations of the black leather chiton) may be due to lost ecosystem functions associated with the Steller's sea cow. This indicates that due to the sea cow's extinction, the ecosystem dynamics and resilience of North Pacific kelp forests may have already been compromised well before more well-known modern stressors like overharvesting

Overexploitation, also called overharvesting, refers to harvesting a renewable resource to the point of diminishing returns. Continued overexploitation can lead to the destruction of the resource, as it will be unable to replenish. The term ap ...

and climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

.

Later reported sightings

Sea cow sightings have been reported after Brandt's official 1768 date of extinction. Lucien Turner, an Americanethnologist

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology) ...

and naturalist, said the natives of Attu Island reported that the sea cows survived into the 1800s, and were sometimes hunted.

In 1963, the official journal of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR

The Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union was the highest scientific institution of the Soviet Union from 1925 to 1991, uniting the country's leading scientists, subordinated directly to the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (until 1946 ...

published an article announcing a possible sighting. The previous year, the whaling ship

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

''Buran'' had reported a group of large marine mammals grazing on seaweed in shallow water off Kamchatka

The Kamchatka Peninsula (russian: полуостров Камчатка, Poluostrov Kamchatka, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and west ...

, in the Gulf of Anadyr

The Gulf of Anadyr, or Anadyr Bay (russian: Анадырский залив), is a large bay on the Bering Sea in far northeast Siberia. It has a total surface area of

Location

The bay is roughly rectangular and opens to the southeast. The corn ...

. The crew reported seeing six of these animals ranging from , with trunks and split lips. There have also been alleged sightings by local fishermen in the northern Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

, and around the Kamchatka and Chukchi peninsulas.

Uses

Steller's sea cow was described as being "tasty" by Steller; the meat was said to have a taste similar to corned beef, though it was tougher, redder, and needed to be cooked longer. The meat was abundant on the animal, and slow to spoil, perhaps due to the high amount of salt in the animal's diet effectively curing it. The fat could be used for cooking and as an odorless lamp oil. The crew of the St. Peter drank the fat in cups and Steller described it as having a taste likealmond oil

The almond (''Prunus amygdalus'', syn. ''Prunus dulcis'') is a species of tree native to Iran and surrounding countries, including the Levant. The almond is also the name of the edible and widely cultivated seed of this tree. Within the genus ...

. The thick, sweet milk of female sea cows could be drunk or made into butter

Butter is a dairy product made from the fat and protein components of churned cream. It is a semi-solid emulsion at room temperature, consisting of approximately 80% butterfat. It is used at room temperature as a spread, melted as a condimen ...

, and the thick, leathery hide could be used to make clothing, such as shoes and belts, and large skin boats sometimes called baidarkas or umiak

The umiak, umialak, umiaq, umiac, oomiac, oomiak, ongiuk, or anyak is a type of open skin boat, used by both Yupik and Inuit, and was originally found in all coastal areas from Siberia to Greenland. First arising in Thule times, it has tradition ...

s.

Towards the end of the 19th century, bones and fossils from the extinct animal were valuable and often sold to museums at high prices. Most were collected during this time, limiting trade after 1900. Some are still sold commercially, as the highly dense cortical bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, and ...

is well-suited for making items such as knife handles and decorative carvings. Because the sea cow is extinct, native artisan products made in Alaska from this "mermaid ivory" are legal to sell in the United States and do not fall under the jurisdiction of the Marine Mammal Protection Act

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) was the first act of the United States Congress to call specifically for an ecosystem approach to wildlife management.

Authority

MMPA was signed into law on October 21, 1972, by President Richard Nixon ...

(MMPA) or the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of intern ...

(CITES), which restrict the trade of marine mammal products. Although the distribution is legal, the sale of unfossilized bones is generally prohibited and trade in products made of the bones is regulated because some of the material is unlikely to be authentic and probably comes from arctic cetaceans.

The ethnographer

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject o ...

Elizabeth Porfirevna Orlova, from the Russian Museum of Ethnography

The Russian Museum of Ethnography (Российский этнографический музей) is a museum in St. Petersburg that houses a collection of about 500,000 items relating to the ethnography, or cultural anthropology, of peoples of ...

, was working on the Commander Island Aleuts from August to September 1961. Her research includes notes about a game of accuracy, called ''kakan'' ("stones") played with the bones of the Steller's sea cow. Kakan was usually played at home between adults during bad weather, at least during Orlova's fieldwork.

In media and folklore

In the story ''The White Seal'' from ''

In the story ''The White Seal'' from ''The Jungle Book

''The Jungle Book'' (1894) is a collection of stories by the English author Rudyard Kipling. Most of the characters are animals such as Shere Khan the tiger and Baloo the bear, though a principal character is the boy or "man-cub" Mowgli, w ...

'' by Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

, which takes place in the Bering Sea, Kotick the rare white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to imp ...

consults Sea Cow during his journey to find a new home.

''Tales of a Sea Cow'' is a 2012 docufiction

Docufiction (or docu-fiction) is the cinematographic combination of documentary and fiction, this term often meaning narrative film. It is a film genre which attempts to capture reality such as it is (as direct cinema or cinéma vérité) a ...

film by Icelandic-French artist Etienne de France about a fictional 2006 discovery of Steller's sea cows off the coast of Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland i ...

. The film has been exhibited in art museums and universities in Europe.

Steller's sea cows appear in two books of poetry: '' Nach der Natur'' (1995) by Winfried Georg Sebald, and '' Species Evanescens'' (2009) by Russian poet Andrei Bronnikov. Bronnikov's book depicts the events of the Great Northern Expedition through the eyes of Steller; Sebald's book looks at the conflict between man and nature, including the extinction of Steller's sea cow.

See also

* Holocene extinction * List of extinct animals of North America * List of Asian animals extinct in the Holocene * List of recently extinct mammals *Evolution of sirenians

Sirenia is the order of placental mammals which comprises modern "sea cows" (manatees and the Dugong) and their extinct relatives. They are the only extant herbivorous marine mammals and the only group of herbivorous mammals to have become com ...

* Cuesta sea cow

The Cuesta sea cow (''Hydrodamalis cuestae'') is an extinct herbivorous marine mammal and is the direct ancestor of the Steller's sea cow (''Hydrodamalis gigas''). They reached up to in length, making them among the biggest sirenians to have eve ...

* Takikawa sea cow

References

Further reading

* *External links

Animal Diversity Web

Steller's sea cow information from the BBC

{{Authority control Extinct mammals of North America Extinct mammals of Asia Species made extinct by human activities Pleistocene sirenians Mammal extinctions since 1500 Sirenians Mammals described in 1780 Taxa named by Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann Commander Islands Extinct animals of Russia Extinct animals of the United States