Stanisław Lem on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

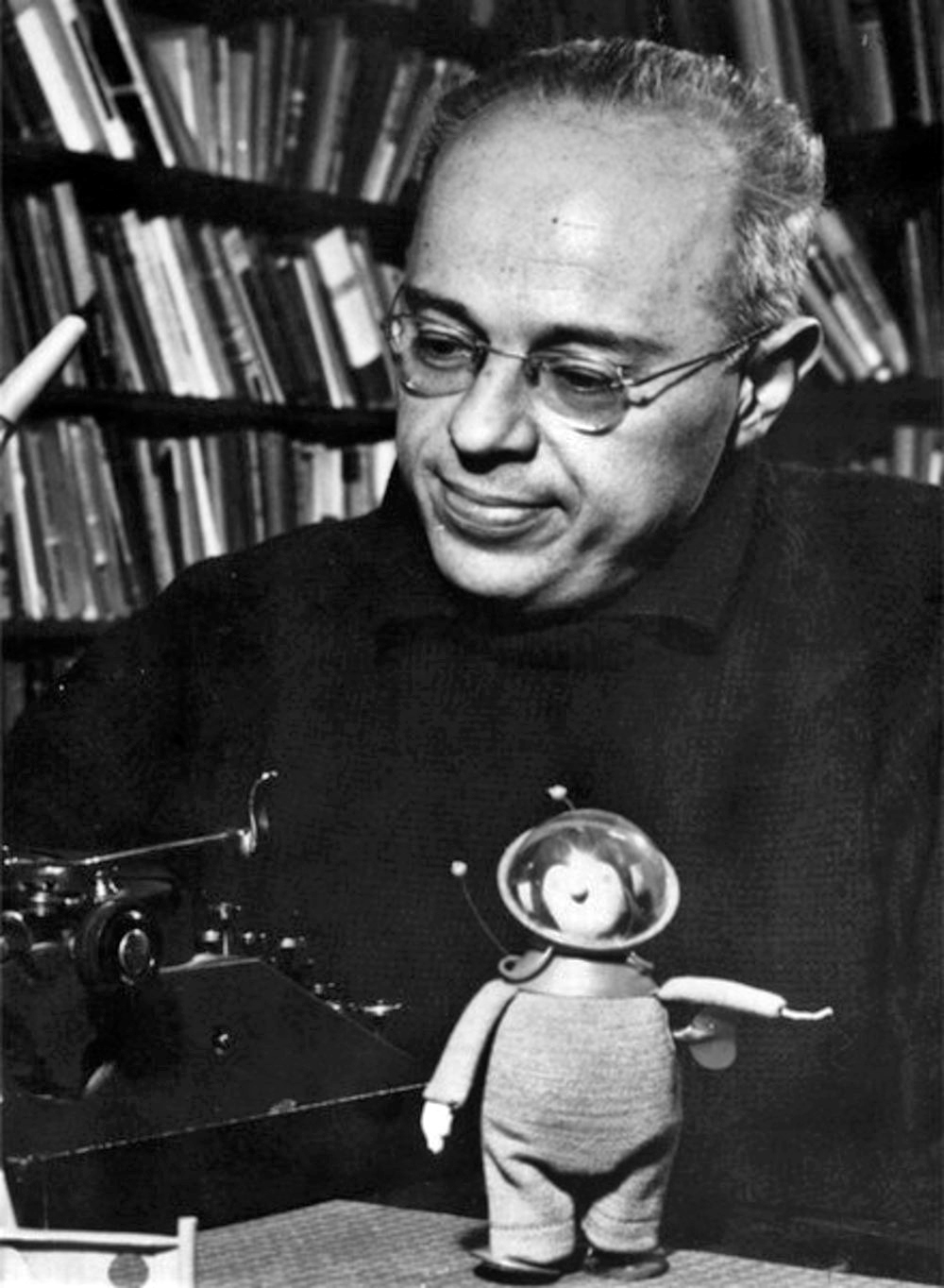

Stanisław Herman Lem (; 12 September 1921 – 27 March 2006) was a Polish writer of science fiction and essays on various subjects, including philosophy,

Lem was born in 1921 in Lwów,

Lem was born in 1921 in Lwów,

"Przyczynek do biografii Stanisława Lema"

(retrieved 16 February 2020), ''Acta Polonica Monashiensis ''(

Lem started his literary work in 1946 with a number of publications in different genres, including poetry, as well as his first science fiction novel, '' The Man from Mars'' (''Człowiek z Marsa''), serialized in ' (''New World of Adventures''). Between 1948 and 1950 Lem was working as a scientific research assistant at the

Lem started his literary work in 1946 with a number of publications in different genres, including poetry, as well as his first science fiction novel, '' The Man from Mars'' (''Człowiek z Marsa''), serialized in ' (''New World of Adventures''). Between 1948 and 1950 Lem was working as a scientific research assistant at the  1965 saw the publication of ''

1965 saw the publication of ''

, Matt Davies, 29 April 2015 There were several attempts to explain Dick's act. Lem was responsible for the Polish translation of Dick's work ''

Lem is one of the most highly acclaimed science fiction writers, hailed by critics as equal to such classic authors as H. G. Wells and

Lem is one of the most highly acclaimed science fiction writers, hailed by critics as equal to such classic authors as H. G. Wells and

, January 21, 2021

Lem was a

Lem was a

forum.lem.pl

internet forum about Lem and his works *

Lemopedia, The Lem Encyclopedia

wiki * * *

Stanisław Lem: Did the Holocaust Shape His Sci-Fi World?

from Culture.pl {{DEFAULTSORT:Lem, Stanislaw 1921 births 2006 deaths 20th-century atheists 20th-century essayists 20th-century Polish Jews 20th-century Polish non-fiction writers 20th-century Polish novelists 20th-century Polish philosophers 20th-century Polish writers 20th-century scholars 20th-century short story writers 21st-century atheists 21st-century essayists 21st-century Polish Jews 21st-century Polish non-fiction writers 21st-century Polish novelists 21st-century Polish philosophers 21st-century Polish writers 21st-century scholars 21st-century short story writers Anti-capitalists Artificial intelligence ethicists Artificial intelligence researchers Atheist philosophers Burials at Salwator Cemetery Communication theorists Crime fiction writers Cultural critics Futurologists Hyperreality theorists Independent scholars Jagiellonian University alumni Jewish atheists Jewish humorists Jewish non-fiction writers Jewish philosophers Jewish Polish writers Literacy and society theorists Literary theorists Mass media theorists Neologists People from Lwów Voivodeship People with diabetes Philosophers of science Philosophers of social science Philosophers of technology Polish atheists Polish essayists Polish humorists Polish literary critics Polish male non-fiction writers Polish male writers Polish philosophers Polish satirists Polish sceptics Polish science fiction writers Polish speculative fiction critics Princeton University alumni Psychological fiction writers Recipients of the Order of Polonia Restituta (1944–1989) Recipients of the Order of the Banner of Work Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Science fiction critics Science fiction fans Social commentators Social critics Social philosophers Surrealist writers Theorists on Western civilization University of Lviv alumni Writers about communism Writers about religion and science Writers from Kraków Writers from Lviv

futurology

Futures studies, futures research, futurism or futurology is the systematic, interdisciplinary and holistic study of social and technological advancement, and other environmental trends, often for the purpose of exploring how people will li ...

, and literary criticism

Literary criticism (or literary studies) is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical discussion of literature's goals and methods. ...

. Many of his science fiction stories are of satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or ...

and humorous character. Lem's books have been translated into more than 50 languages and have sold more than 45 million copies. Worldwide, he is best known as the author of the 1961 novel '' Solaris''. In 1976 Theodore Sturgeon

Theodore Sturgeon (; born Edward Hamilton Waldo, February 26, 1918 – May 8, 1985) was an American fiction author of primarily fantasy, science fiction and horror, as well as a critic. He wrote approximately 400 reviews and more than 120 sh ...

wrote that Lem was the most widely read science fiction writer in the world.

Lem is the author of the fundamental philosophical work "Summa Technologiae

''Summa Technologiae'' (the title is in Latin, meaning "Summa (Compendium) of Technology" in English) is a 1964 book by Polish author Stanisław Lem. ''Summa'' is one of the first collections of philosophical essays by Lem. The book exhibits d ...

", in which he anticipated the creation of virtual reality

Virtual reality (VR) is a simulated experience that employs pose tracking and 3D near-eye displays to give the user an immersive feel of a virtual world. Applications of virtual reality include entertainment (particularly video games), edu ...

, artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is intelligence—perceiving, synthesizing, and inferring information—demonstrated by machines, as opposed to intelligence displayed by animals and humans. Example tasks in which this is done include speech ...

, and also developed the ideas of human autoevolution, the creation of artificial worlds, and many others. Lem's science fiction works explore philosophical themes through speculations on technology, the nature of intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. More generally, it can ...

, the impossibility of communication with and understanding of alien intelligence, despair about human limitations, and humanity's place in the universe. His essays and philosophical books cover these and many other topics.

Translating his works is difficult due to Lem's elaborate neologisms and idiomatic wordplay. The Polish Parliament declared 2021 Stanisław Lem Year.

Life

Early life

Lem was born in 1921 in Lwów,

Lem was born in 1921 in Lwów, interwar Poland

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

(now Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

, Ukraine) to a Jewish family

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites"" ...

. According to his own account, he was actually born on 13 September, but the date was changed to the 12th on his birth certificate because of superstition. He was the son of Sabina née Woller (1892–1979) and Samuel Lem (1879–1954), a wealthy laryngologist

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about ...

and former physician in the Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army (, literally "Ground Forces of the Austro-Hungarians"; , literally "Imperial and Royal Army") was the ground force of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy from 1867 to 1918. It was composed of three parts: the joint arm ...

, and first cousin to Polish poet Marian Hemar (Lem's father's sister's son). In later years Lem sometimes claimed to have been raised Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

, but he went to Jewish religious lessons during his school years. He later became an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

"for moral reasons ... the world appears to me to be put together in such a painful way that I prefer to believe that it was not created ... intentionally". In later years he would call himself both an agnostic and an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

.

After the 1939 Soviet occupation of western Ukraine and Belarus, he was not allowed to study at Lwow Polytechnic as he wished because of his "bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. ...

origin", and only due to his father's connections he was accepted to study medicine at Lwów University

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

in 1940. During the subsequent Nazi occupation (1941–1944), Lem's Jewish family avoided placement in the Nazi Lwów Ghetto

, location = Lwów, Zamarstynów( German-occupied Poland)

, date = 8 November 1941 to June 1943

, incident_type = Imprisonment, mass shootings, forced labor, starvation, forced abortions and sterilization

, perpetrators =

, pa ...

, surviving with false papers. He would later recall:

During that time, Lem earned a living as a car mechanic and welder, and occasionally stole munitions from storehouses (to which he had access as an employee of a German company) to pass them on to the Polish resistance.

In 1945, Lwow was annexed into the Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

, and the family, along with many other Polish citizens, was resettled to Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

, where Lem, at his father's insistence, took up medical studies at the Jagiellonian University

The Jagiellonian University ( Polish: ''Uniwersytet Jagielloński'', UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and the 13th oldest university in ...

. He did not take his final examinations on purpose, to avoid the career of military doctor, which he suspected could have become lifelong.Lech Keller suggests a slightly different reason why Lem did not pursue the diploma: since his father was a functionary of Sanitary Department of the infamous UB ( Ministry of Public Security), he would have probably been assigned to the hospital subordinated to UB, probably to the same department his father served. Keller further remarks that it was well-known that UB doctors were used to "restore the conditions" of the interrogated dissidents

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 20th ...

. See Lech Keller"Przyczynek do biografii Stanisława Lema"

(retrieved 16 February 2020), ''Acta Polonica Monashiensis ''(

Monash University

Monash University () is a public research university based in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Named for prominent World War I general Sir John Monash, it was founded in 1958 and is the second oldest university in the state. The university has ...

, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) Volume 3 Number 2, R&S Press, Melbourne, Victoria, 2019, pp. 94, 107 After receiving ''absolutorium'' (Polish term for the evidence of completion of the studies without diploma), he did an obligatory monthly work at a hospital, at a maternity ward

Childbirth, also known as labour and delivery, is the ending of pregnancy where one or more babies exits the internal environment of the mother via vaginal delivery or caesarean section. In 2019, there were about 140.11 million births global ...

, where he assisted at a number of childbirths and a caesarean section

Caesarean section, also known as C-section or caesarean delivery, is the surgical procedure by which one or more babies are delivered through an incision in the mother's abdomen, often performed because vaginal delivery would put the baby or m ...

. Lem said that the sight of blood was one of the reasons he decided to drop medicine.

Rise to fame

Lem started his literary work in 1946 with a number of publications in different genres, including poetry, as well as his first science fiction novel, '' The Man from Mars'' (''Człowiek z Marsa''), serialized in ' (''New World of Adventures''). Between 1948 and 1950 Lem was working as a scientific research assistant at the

Lem started his literary work in 1946 with a number of publications in different genres, including poetry, as well as his first science fiction novel, '' The Man from Mars'' (''Człowiek z Marsa''), serialized in ' (''New World of Adventures''). Between 1948 and 1950 Lem was working as a scientific research assistant at the Jagiellonian University

The Jagiellonian University ( Polish: ''Uniwersytet Jagielloński'', UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and the 13th oldest university in ...

, and published a number of short stories, poems, reviews, etc., particularly at ''Tygodnik Powszechny

''Tygodnik Powszechny'' (, ''The Common Weekly'') is a Polish Roman Catholic weekly magazine, published in Kraków, which focuses on social, cultural and political issues. It was established in 1945 under the auspices of Cardinal Adam Stefan Sa ...

''. In 1951, he published his first book, ''The Astronauts

''The Astronauts'' ( Polish: ''Astronauci'') is the first science fiction novel by Polish writer Stanisław Lem published as a book, in 1951.

To write the novel, Lem received advance payment from publishing house Czytelnik (Warsaw). The book b ...

'' (''Astronauci''). In 1953 he met and married (civil marriage

A civil marriage is a marriage performed, recorded, and recognized by a government official. Such a marriage may be performed by a religious body and recognized by the state, or it may be entirely secular.

History

Every country maintaining a ...

) Barbara Leśniak, a medical student.

Their church marriage ceremony was performed in February 1954. In 1954, he published a short story anthology, ' 'Sesame and Other Stories''. The following year, 1955, saw the publication of another science fiction novel, '' The Magellanic Cloud'' (''Obłok Magellana'').

During the era of Stalinism in Poland, which had begun in the late 1940s, all published works had to be directly approved by the communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

. Thus ''The Astronauts'' was not, in fact, the first novel Lem finished, just the first that made it past the state censors. Going by the date of the finished manuscript, Lem's first book was a partly autobiographical novel ''Hospital of the Transfiguration

''Hospital of the Transfiguration'' (in Polish: ''Szpital Przemienienia'') is a book by Polish writer Stanisław Lem. It tells the story of a young doctor, Stefan Trzyniecki, who after graduation starts to work in a psychiatric hospital. The story ...

'' (''Szpital Przemienienia''), finished in 1948. It would be published seven years later, in 1955, as a part of the trilogy '' Czas nieutracony'' (''Time Not Lost''). The experience of trying to push ''Czas nieutracony'' through the censors was one of the major reasons Lem decided to focus on the less-censored genre of science fiction. Nonetheless, most of Lem's works published in the 1950s also contain—forced upon him by the censors and editors—various elements of socialist realism

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is ch ...

as well as of the "glorious future of communism". Lem later criticized several of his early pieces as compromised by the ideological pressure.

Lem became truly productive after 1956, when the de-Stalinization period in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

led to the "Polish October

Polish October (), also known as October 1956, Polish thaw, or Gomułka's thaw, marked a change in the politics of Poland in the second half of 1956. Some social scientists term it the Polish October Revolution, which was less dramatic than the ...

", when Poland experienced an increase in freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

. Between 1956 and 1968, Lem authored seventeen books. His writing over the next three decades or so was split between science fiction and essays about science and culture.

In 1957, he published his first non-fiction, philosophical book, ''Dialogues

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is chi ...

'', as well as a science fiction anthology, ''The Star Diaries

, image = File:TheStarDiaries.jpg

, caption = First edition

, author = Stanisław Lem

, translator = ''English:'' Michael Kandel

, illustrator = Stanisław Lem

, cover_artist = Marian Stachurski

, country = Poland

, language = Polish, Engli ...

'' (''Dzienniki gwiazdowe''), collecting short stories about one of his most popular characters, Ijon Tichy Ijon Tichy (Polish pronunciation: ) is a fictional character who appears in several works of the Polish science fiction writer Stanisław Lem: initially in '' The Star Diaries'', later in '' The Futurological Congress'', '' Peace on Earth'', '' Obse ...

. 1959 saw the publication of three books: '' Eden'', ''The Investigation

''The Investigation'' (original title ''Śledztwo'') is a science fiction/detective/thriller novel by the Polish writer Stanisław Lem. The novel incorporates a philosophical discourse on explanation of unknown phenomena. It was first publishe ...

'' (''Śledztwo'') and the short story anthology ''An Invasion from Aldebaran'' (''Inwazja z Aldebarana''). 1961 saw the novels: ''Memoirs Found in a Bathtub

''Memoirs Found in a Bathtub'' (a literal translation of the original Polish-language title: ''Pamiętnik znaleziony w wannie'') is a science fiction novel by Polish writer Stanisław Lem, first published in 1961. It was first published in English ...

'' (''Pamiętnik znaleziony w wannie''), '' Solaris'', and '' Return from the Stars'' (''Powrót z gwiazd''), with ''Solaris'' being among his top works. This was followed by a collection of his essays and non-fiction prose, ''Wejście na orbitę'' (1962), and a short story anthology ''Noc księżycowa'' (1963). In 1964, Lem published a large work on the border of philosophy and sociology of science and futurology, ''Summa Technologiae

''Summa Technologiae'' (the title is in Latin, meaning "Summa (Compendium) of Technology" in English) is a 1964 book by Polish author Stanisław Lem. ''Summa'' is one of the first collections of philosophical essays by Lem. The book exhibits d ...

'', as well as a novel, ''The Invincible

''The Invincible'' ( pl, Niezwyciężony) is a hard science fiction novel by Polish writer Stanisław Lem, published in 1964.

In 2019, Rafał Mikołajczyk published the comic book ''Niezwyciężony'' 'The Invincible'' . Reviewers note the fait ...

'' (''Niezwyciężony'').

The Cyberiad

''The Cyberiad'' ( pl, Cyberiada) is a series of humorous science fiction short stories by Polish writer Stanisław Lem, originally published in 1965, with an English translation appearing in 1974. The main protagonists of the series are Trurl a ...

'' (''Cyberiada'') and of a short story anthology, ''The Hunt'' (). 1966 is the year of '' Highcastle'' (Polish title: ''Wysoki Zamek''), followed in 1968 by ''His Master's Voice

His Master's Voice (HMV) was the name of a major British record label created in 1901 by The Gramophone Co. Ltd. The phrase was coined in the late 1890s from the title of a painting by English artist Francis Barraud, which depicted a Jack Russ ...

'' (''Głos Pana'') and '' Tales of Pirx the Pilot'' (''Opowieści o pilocie Pirxie''). ''Highcastle'' was another of Lem's autobiographical works, and touched upon a theme that usually was not favored by the censors: Lem's youth in the pre-war, then-Polish, Lviv. 1968 and 1970 saw two more non-fiction treatises, '' The Philosophy of Chance'' (''Filozofia przypadku'') and ''Science Fiction and Futurology

''Science Fiction and Futurology'' ( pl, Fantastyka i futurologia) is a monograph of Stanisław Lem about science fiction and futurology, first printed by Wydawnictwo Literackie in 1970.

The official Lem website describes the book as a triple f ...

'' (''Fantastyka i futurologia''). Ijon Tichy returned in 1971's ''The Futurological Congress

''The Futurological Congress'' ( pl, Kongres futurologiczny) is a 1971 black humour science fiction novel by Polish author Stanisław Lem. It details the exploits of the hero of a number of his stories, Ijon Tichy, as he visits the Eighth World Fu ...

'' ''Kongres futurologiczny''; in the same year Lem released a genre-mixing experiment, '' Doskonała próżnia'', a collection of reviews of non-existent books. In 1973 a similar work, ''Imaginary Magnitude

Imaginary may refer to:

* Imaginary (sociology), a concept in sociology

* The Imaginary (psychoanalysis), a concept by Jacques Lacan

* Imaginary number, a concept in mathematics

* Imaginary time, a concept in physics

* Imagination, a mental fa ...

'' (''Wielkość urojona''), was published. In 1976, Lem published two novels: ''Maska'' (''The Mask The Mask may refer to:

Books and comics

* ''The Mask'' (comics), a comic book series by publisher Dark Horse Comics

* Mask (DC Comics), an opponent of Wonder Woman

* ''The Mask'' (novel), a 1981 novel written by Dean Koontz under the pseudonym ...

'') and ''Katar'' (translated as ''The Chain of Chance

''The Chain of Chance'' (original Polish title: ''Katar'', literally, "Rhinitis"/Catarrh) is a science fiction/detective novel by the Polish writer Stanisław Lem, published in 1976. Lem's treatment of the detective genre introduces many nontra ...

''). In 1980, he published another set of reviews of non-existent works, '' Prowokacja''. The following year sees another Tichy novel, '' Wizja lokalna'', and '' Golem XIV''. Later in that decade, Lem published '' Pokój na Ziemi'' (1984) and ''Fiasco

Fiasco may refer to:

* a failure or humiliating situation

* Fiasco (bottle), a traditional Italian straw-covered wine bottle often associated with Chianti wine

Media

* ''Fiasco'' (novel), a 1987 science-fiction novel by Stanisław Lem

* '' ...

'' (1986), his last science fiction novel.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Lem cautiously supported the Polish dissident movement, and started publishing essays in Paris-based ''Kultura

''Kultura'' (, ''Culture'')—sometimes referred to as ''Kultura Paryska'' ("Paris-based Culture")—was a leading Polish-émigré literary-political magazine, published from 1947 to 2000 by ''Instytut Literacki'' (the Literary Institute), ini ...

''. In 1982, with martial law in Poland declared, Lem moved to West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

, where he became a fellow of the Institute for Advanced Study, Berlin

The Institute for Advanced Study in Berlin (german: Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin) is an interdisciplinary institute founded in 1981 in Grunewald, Berlin, Germany, dedicated to research projects in the natural and social sciences. It is model ...

(''Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin''). After that, he settled in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. He returned to Poland in 1988.

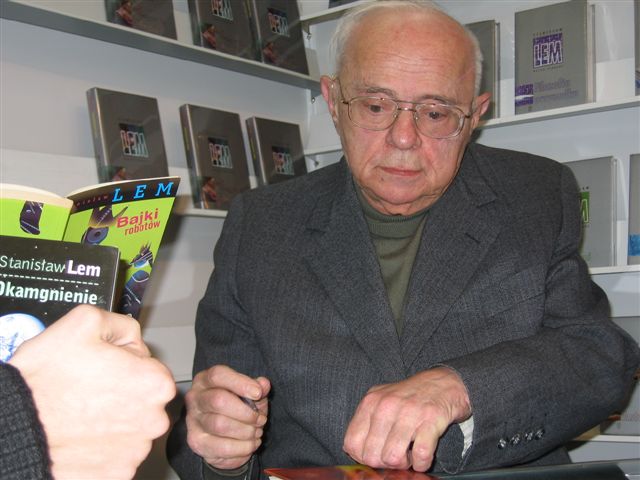

Final years

From the late 1980s onwards, he tended to concentrate on philosophical texts and essays, published in Polish magazines (''Tygodnik Powszechny

''Tygodnik Powszechny'' (, ''The Common Weekly'') is a Polish Roman Catholic weekly magazine, published in Kraków, which focuses on social, cultural and political issues. It was established in 1945 under the auspices of Cardinal Adam Stefan Sa ...

'', '' Odra'', ''Przegląd

Przegląd (English: ''Review'') is a weekly Polish news and opinion magazine published in Warsaw, Poland.

History and profile

''Przegląd'' was started in 1990 as the successor of another weekly, ''Przegląd Tygodniowy'', which had been published ...

'', and others). They were later collected in a number of anthologies.

In early 1980s literary critic and historian Stanisław Bereś

Stanisław Bereś (born 4 May 1950) is a Polish poet, literary critic, translator and literary historian.

conducted a lengthy interview with Lem, which was published in book format in 1987 as '' Rozmowy ze Stanisławem Lemem'' (''Conversations with Stanisław Lem)''. That edition was subject to censorship. A revised, complete edition was published in 2002 as ''Tako rzecze… Lem'' (''Thus spoke... Lem'').

In the early 1990s, Lem met with the literary critic and scholar Peter Swirski for a series of extensive interviews, published together with other critical materials and translations as '' A Stanislaw Lem Reader'' (1997). In these interviews Lem speaks about a range of issues he rarely discussed previously. The book also includes Swirski's translation of Lem's retrospective essay "Thirty Years Later", devoted to Lem's nonfictional treatise ''Summa Technologiae

''Summa Technologiae'' (the title is in Latin, meaning "Summa (Compendium) of Technology" in English) is a 1964 book by Polish author Stanisław Lem. ''Summa'' is one of the first collections of philosophical essays by Lem. The book exhibits d ...

''. During later interviews in 2005, Lem expressed his disappointment with the genre of science fiction, and his general pessimism regarding technical progress. He viewed the human body as unsuitable for space travel, held that information technology drowns people in a glut of low-quality information, and considered truly intelligent robots as both undesirable and impossible to construct.

Writings

Science fiction

Lem's prose shows a mastery of numerous genres and themes.Recurring themes

One of Lem's major recurring themes, beginning from his very first novel, '' The Man from Mars'', was the impossibility of communication between profoundly alien beings, which may have no common ground with human intelligence, and humans. The best known example is the living planetary ocean in Lem's novel '' Solaris''. Other examples include intelligent swarms of mechanical insect-like micromachines (in ''The Invincible

''The Invincible'' ( pl, Niezwyciężony) is a hard science fiction novel by Polish writer Stanisław Lem, published in 1964.

In 2019, Rafał Mikołajczyk published the comic book ''Niezwyciężony'' 'The Invincible'' . Reviewers note the fait ...

''), and strangely ordered societies of more human-like beings in ''Fiasco

Fiasco may refer to:

* a failure or humiliating situation

* Fiasco (bottle), a traditional Italian straw-covered wine bottle often associated with Chianti wine

Media

* ''Fiasco'' (novel), a 1987 science-fiction novel by Stanisław Lem

* '' ...

'' and '' Eden'', describing the failure of the first contact.

Another key recurring theme is the shortcomings of humans. In ''His Master's Voice

His Master's Voice (HMV) was the name of a major British record label created in 1901 by The Gramophone Co. Ltd. The phrase was coined in the late 1890s from the title of a painting by English artist Francis Barraud, which depicted a Jack Russ ...

'', Lem describes the failure of humanity's intelligence to decipher and truly comprehend an apparent message from space. Two overlapping arcs of short stories, ''Fables for Robots

''Fables for Robots'' ( pl, Bajki Robotów) is a series of humorous science fiction short stories by Polish writer Stanisław Lem, first printed in 1964.

The fables are written in the grotesque form of folk fairy tales, set in the universe pop ...

'' (''Bajki Robotów'', translated in the collection '' Mortal Engines''), and ''The Cyberiad

''The Cyberiad'' ( pl, Cyberiada) is a series of humorous science fiction short stories by Polish writer Stanisław Lem, originally published in 1965, with an English translation appearing in 1974. The main protagonists of the series are Trurl a ...

'' (''Cyberiada'') provide a commentary on humanity in the form of a series of grotesque

Since at least the 18th century (in French and German as well as English), grotesque has come to be used as a general adjective for the strange, mysterious, magnificent, fantastic, hideous, ugly, incongruous, unpleasant, or disgusting, and thus ...

, humorous, fairytale-like short stories about a mechanical universe inhabited by robots (who have occasional contact with biological "slimies" and human "palefaces"). Lem also underlines the uncertainties of evolution, including that it might not progress upwards in intelligence.

Other writings

''Śledztwo'' and ''Katar'' arecrime novel

Crime fiction, detective story, murder mystery, mystery novel, and police novel are terms used to describe narratives that centre on criminal acts and especially on the investigation, either by an amateur or a professional detective, of a crime, ...

s (the latter without a murderer); ''Pamiętnik...'' is a psychological drama inspired by Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a German-speaking Bohemian novelist and short-story writer, widely regarded as one of the major figures of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of realism and the fantastic. It typi ...

. ''Doskonała próżnia'' and ''Wielkość urojona'' are collections of reviews of and introductions to non-existent books. Similarly, ''Prowokacja'' purports to review a (non-existing) Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

-themed work.

Essays

'' Dialogs'' and ''Summa Technologiae

''Summa Technologiae'' (the title is in Latin, meaning "Summa (Compendium) of Technology" in English) is a 1964 book by Polish author Stanisław Lem. ''Summa'' is one of the first collections of philosophical essays by Lem. The book exhibits d ...

'' (1964) are Lem's two most famous philosophical texts. The ''Summa'' is notable for being a unique analysis of prospective social, cybernetic, and biological advances; in this work, Lem discusses philosophical implications of technologies that were completely in the realm of science fiction at the time, but are gaining importance today—for instance, virtual reality

Virtual reality (VR) is a simulated experience that employs pose tracking and 3D near-eye displays to give the user an immersive feel of a virtual world. Applications of virtual reality include entertainment (particularly video games), edu ...

and nanotechnology

Nanotechnology, also shortened to nanotech, is the use of matter on an atomic, molecular, and supramolecular scale for industrial purposes. The earliest, widespread description of nanotechnology referred to the particular technological goal ...

.

Views in later life

Lem's criticism of most science fiction surfaced in literary and philosophical essays ''Science Fiction and Futurology

''Science Fiction and Futurology'' ( pl, Fantastyka i futurologia) is a monograph of Stanisław Lem about science fiction and futurology, first printed by Wydawnictwo Literackie in 1970.

The official Lem website describes the book as a triple f ...

'' and interviews. In the 1990s, Lem forswore science fiction and returned to futurological prognostications, most notably those expressed in ' 'Blink of an Eye''.

Lem said that since the success of Solidarność

Solidarity ( pl, „Solidarność”, ), full name Independent Self-Governing Trade Union "Solidarity" (, abbreviated ''NSZZ „Solidarność”'' ), is a Polish trade union founded in August 1980 at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, Poland. Subseq ...

, and the collapse of the Soviet empire, he felt his wild dreams about the future could no longer compare with reality.

He became increasingly critical of modern technology in his later life, criticizing inventions such as the Internet, which he said "makes it easier to hurt our neighbors."

Relationship with American science fiction

SFWA

Lem was awarded an honorary membership in theScience Fiction Writers of America

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, doing business as Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, commonly known as SFWA ( or ) is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization of professional science fiction and fantasy

Fantas ...

(SFWA) in 1973. SFWA honorary membership is given to people who do not meet the publishing criteria for joining the regular membership, but who would be welcomed as members had their work appeared in the qualifying English-language publications. Lem never had a high opinion of American science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel universe ...

, describing it as ill-thought-out, poorly written, and interested more in making money than in ideas or new literary forms. After his eventual American publication, when he became eligible for regular membership, his honorary membership was rescinded. This formal action was interpreted by some of the SFWA members as a rebuke for his stance, and it seems that Lem interpreted it as such. Lem was invited to stay on with the organization with a regular membership, but he declined. After many members (including Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin (; October 21, 1929 – January 22, 2018) was an American author best known for her works of speculative fiction, including science fiction works set in her Hainish universe, and the '' Earthsea'' fantasy series. She was ...

, who quit her membership and then refused the Nebula Award for Best Novelette

The Nebula Award for Best Novelette is given each year by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) to a science fiction or fantasy novelette. A work of fiction is defined by the organization as a novelette if it is between 7,50 ...

for ''The Diary of the Rose

"The Diary of the Rose" is a 1976 dystopian science fiction novelette by Ursula K. Le Guin, first published in the ''Future Power'' collection. The tale is set in a totalitarian society which uses brainwashing by "electroshocks" to eradicate any k ...

'') protested against Lem's treatment by the SFWA, a member offered to pay his dues. Lem never accepted the offer.

Philip K. Dick

Lem singled out only one American science fiction writer for praise, Philip K. Dick, in a 1984 English-language anthology of his critical essays, '' Microworlds: Writings on Science Fiction and Fantasy''. Lem had initially held a low opinion of Philip K. Dick (as he did for the bulk of American science fiction) and would later say that this was due to a limited familiarity with Dick's work, since Western literature was hard to come by inCommunist Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

.

Dick alleged that Stanisław Lem was probably a false name used by a composite committee operating on orders of the Communist party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

to gain control over public opinion, and wrote a letter to the FBI to that effect."Philip K. Dick: Stanisław Lem is a Communist Committee", Matt Davies, 29 April 2015 There were several attempts to explain Dick's act. Lem was responsible for the Polish translation of Dick's work ''

Ubik

''Ubik'' ( ) is a 1969 science fiction novel by American writer Philip K. Dick. The story is set in a future 1992 where psychic powers are utilized in corporate espionage, while cryonic technology allows recently deceased people to be maintaine ...

'' in 1972, and when Dick felt monetarily short-changed by the publisher, he held Lem personally responsible (see ''Microworlds

MicroWorlds is a program that uses the Logo programming language to teach language, mathematics, programming, and robotics concepts in primary and secondary education. It features an object in the shape of a turtle that can be given commands to m ...

''). Also it was suggested that Dick was under the influence of strong medications, including opioids, and may have experienced a "slight disconnect from reality" some time before writing the letter. A "defensive patriotism" of Dick against Lem's attacks on American science fiction may have played some role as well. Lem would later mention Philip Dick in his monograph ''Science Fiction and Futurology

''Science Fiction and Futurology'' ( pl, Fantastyka i futurologia) is a monograph of Stanisław Lem about science fiction and futurology, first printed by Wydawnictwo Literackie in 1970.

The official Lem website describes the book as a triple f ...

''.

Significance

Writing

Lem is one of the most highly acclaimed science fiction writers, hailed by critics as equal to such classic authors as H. G. Wells and

Lem is one of the most highly acclaimed science fiction writers, hailed by critics as equal to such classic authors as H. G. Wells and Olaf Stapledon

William Olaf Stapledon (10 May 1886 – 6 September 1950) – known as Olaf Stapledon – was a British philosopher and author of science fiction.Andy Sawyer, " illiamOlaf Stapledon (1886-1950)", in Bould, Mark, et al, eds. ''Fifty Key Figures ...

. In 1976, Theodore Sturgeon

Theodore Sturgeon (; born Edward Hamilton Waldo, February 26, 1918 – May 8, 1985) was an American fiction author of primarily fantasy, science fiction and horror, as well as a critic. He wrote approximately 400 reviews and more than 120 sh ...

wrote that Lem was the most widely read science fiction writer in the world. In Poland, in the 1960s and 1970s, Lem remained under the radar of mainstream critics, who dismissed him as a "mass market", low-brow, youth-oriented writer; such dismissal might have given him a form of invisibility from censorship. His works were widely translated abroad, appearing in over 40 languages. and have sold over 45 million copies. , about 1.5 million copies were sold in Poland after his death, with the annual numbers of 100,000 matching the new bestsellers."2021. to będzie dobry rok ?!? O Stanisławie Lemie, patronie tego roku, opowiada prof. Stanisław Bereś z Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego", January 21, 2021

Franz Rottensteiner Franz Rottensteiner (born 18 January 1942) is an Austrian publisher and critic in the fields of science fiction and speculative fiction in general.

Biography

Rottensteiner was born in Waidmannsfeld, Lower Austria.

He studied journalism, Englis ...

, Lem's former agent abroad, had this to say about Lem's reception on international markets:

Influence

Will Wright's popular city-planning game ''SimCity

''SimCity'' is an open-ended city-building video game series originally designed by Will Wright. The first game in the series, ''SimCity'', was published by Maxis in 1989 and were followed by several sequels and many other spin-off "''Sim ...

'' was partly inspired by Lem's short story '' The Seventh Sally''.

The video game Stellaris is highly inspired by his works, as its creators said at the start of 2021 ( Year of Lem)

A major character in the film '' Planet 51'', an alien Lem, was named by screenwriter Joe Stillman after Stanisław Lem. Since the film was intended to be a parody of American pulp science fiction

Pulp magazines (also referred to as "the pulps") were inexpensive fiction magazines that were published from 1896 to the late 1950s. The term "pulp" derives from the cheap wood pulp paper on which the magazines were printed. In contrast, magazine ...

shot in Eastern Europe, Stillman thought that it would be hilarious to hint at the writer whose works have nothing to do with little green men

Little green men is the stereotypical portrayal of extraterrestrials as little humanoid creatures with green skin and sometimes with antennae on their heads. The term is also sometimes used to describe gremlins, mythical creatures known for cau ...

.

Film critics have noted the influence of Andrei Tarkovsky's cinematic adaptation of '' Solaris'' on later science fiction films such as ''Event Horizon'' (1997) and Christopher Nolan

Christopher Edward Nolan (born 30 July 1970) is a British-American filmmaker. Known for his lucrative Hollywood blockbusters with complex storytelling, Nolan is considered a leading filmmaker of the 21st century. His films have grossed $5&nb ...

's ''Inception

''Inception'' is a 2010 science fiction action film written and directed by Christopher Nolan, who also produced the film with Emma Thomas, his wife. The film stars Leonardo DiCaprio as a professional thief who steals information by infi ...

'' (2010).

Adaptations of Lem's works

''Solaris'' was made into a film in 1968 by Russian director Boris Nirenburg, a film in 1972 by Russian directorAndrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky ( rus, Андрей Арсеньевич Тарковский, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ɐrˈsʲenʲjɪvʲɪtɕ tɐrˈkofskʲɪj; 4 April 1932 – 29 December 1986) was a Russian filmmaker. Widely considered one of the greates ...

—which won a Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Festival (; french: link=no, Festival de Cannes), until 2003 called the International Film Festival (') and known in English as the Cannes Film Festival, is an annual film festival held in Cannes, France, which previews new films ...

in 1972—and an American film in 2002 by Steven Soderbergh

Steven Andrew Soderbergh (; born January 14, 1963) is an American film director, producer, screenwriter, cinematographer and editor. A pioneer of modern independent cinema, Soderbergh is an acclaimed and prolific filmmaker.

Soderbergh's direct ...

.

A number of other dramatic and musical adaptations of his work exist, such as adaptations of ''The Astronauts'' (''First Spaceship on Venus

''Milcząca Gwiazda'' (german: Der schweigende Stern), literal English translation ''The Silent Star'', is a 1960 East German/Polish color science fiction film based on the 1951 science fiction novel ''The Astronauts'' by Polish science fiction wri ...

'', 1960) and ''The Magellan Nebula'' ('' Ikarie XB-1'', 1963). Lem himself was, however, critical of most of the screen adaptations, with the sole exception of '' Przekładaniec'' in 1968 by Andrzej Wajda

Andrzej Witold Wajda (; 6 March 1926 – 9 October 2016) was a Polish film and theatre director. Recipient of an Honorary Oscar, the Palme d'Or, as well as Honorary Golden Lion and Honorary Golden Bear Awards, he was a prominent member of the ...

. In 2013, the Israeli–Polish co-production '' The Congress'' was released, inspired by Lem's novel ''The Futurological Congress

''The Futurological Congress'' ( pl, Kongres futurologiczny) is a 1971 black humour science fiction novel by Polish author Stanisław Lem. It details the exploits of the hero of a number of his stories, Ijon Tichy, as he visits the Eighth World Fu ...

''.

In 2018 with the directing of György Pálfi a film adaptation of His Master's Voice

His Master's Voice (HMV) was the name of a major British record label created in 1901 by The Gramophone Co. Ltd. The phrase was coined in the late 1890s from the title of a painting by English artist Francis Barraud, which depicted a Jack Russ ...

was made with the same title.

Honors

Awards

* 1957 – City of Kraków's Prize in Literature (''Nagroda Literacka miasta Krakowa'') * 1965 – Prize of the Minister of Culture and Art, 2nd Level (''Nagroda Ministra Kultury i Sztuki II stopnia'') * 1973 ** Prize of the Minister of Foreign Affairs for popularization of Polish culture abroad (''nagroda Ministra Spraw Zagranicznych za popularyzację polskiej kultury za granicą'') ** Literary Prize of the Minister of Culture and Art (''nagroda literacka Ministra Kultury i Sztuki'') and honorary member ofScience Fiction Writers of America

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, doing business as Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, commonly known as SFWA ( or ) is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization of professional science fiction and fantasy

Fantas ...

* 1976 – State Prize 1st Level in the area of literature (''Nagroda Państwowa I stopnia w dziedzinie literatury'')

* 1979 – Grand Prix de Littérature Policière The Grand Prix de Littérature Policière (or the Police Literature Grand Prize) is a French literary prize founded in 1948 by author and literary critic Maurice-Bernard Endrèbe. It is the most prestigious award for crime and detective fiction in ...

for his novel ''Katar''.

* 1986 – Austrian State Prize for European Literature The Austrian State Prize for European Literature (german: Österreichischer Staatspreis für Europäische Literatur), also known in Austria as the European Literary Award (''Europäischer Literaturpreis''), is an Austria

Austria, , bar, Ö ...

for year 1985

* 1991 – Austrian literary

* 1996 – recipient of the Order of the White Eagle

* 2005 – Medal for Merit to Culture – Gloria Artis

A medal or medallion is a small portable artistic object, a thin disc, normally of metal, carrying a design, usually on both sides. They typically have a commemorative purpose of some kind, and many are presented as awards. They may be int ...

(on the list of the first recipients of the newly introduced medal)

Recognition and remembrance

* 1972 – member of commission "Poland 2000" of thePolish Academy of Sciences

The Polish Academy of Sciences ( pl, Polska Akademia Nauk, PAN) is a Polish state-sponsored institution of higher learning. Headquartered in Warsaw, it is responsible for spearheading the development of science across the country by a society o ...

* 1979 – a minor planet

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''minor ...

, 3836 Lem, discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh

Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh (russian: Никола́й Степа́нович Черны́х) (6 October 1931 – 25 May 2004Казакова, Р.К. Памяти Николая Степановича Черных'. Труды Государст ...

is named after him.

* 1981 – ''Doctor honoris causa'' honorary degree from the Wrocław University of Technology

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

* 1986 – the whole issue (#40 = Volume 13, Part 3) of ''Science Fiction Studies

''Science Fiction Studies'' (''SFS'') is an academic journal founded in 1973 by R. D. Mullen. The journal is published three times per year at DePauw University. As the name implies, the journal publishes articles and book reviews on science fic ...

'' was dedicated to Stanislaw Lem

* 1994 – member of the Polish Academy of Learning

The Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences or Polish Academy of Learning ( pl, Polska Akademia Umiejętności), headquartered in Kraków and founded in 1872, is one of two institutions in contemporary Poland having the nature of an academy of scie ...

* 1997 – honorary citizen

Honorary citizenship is a status bestowed by a city or other government on a foreign or native individual whom it considers to be especially admirable or otherwise worthy of the distinction. The honour usually is symbolic and does not confer an ...

of Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

* 1998 – ''Doctor honoris causa'': University of Opole

The University of Opole ( pl, Uniwersytet Opolski) is a public university in the city of Opole. It was founded in 1994 from a merger of two parallel educational institutions. The university has 17,500 students completing 32 academic majors and 53 ...

, Lviv University

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

, Jagiellonian University

The Jagiellonian University ( Polish: ''Uniwersytet Jagielloński'', UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and the 13th oldest university in ...

* 2003 – ''Doctor honoris causa'' of the University of Bielefeld

Bielefeld University (german: Universität Bielefeld) is a university in Bielefeld, Germany. Founded in 1969, it is one of the country's newer universities, and considers itself a "reform" university, following a different style of organizatio ...

* 2007 – A street in Kraków is to be named in his honour.

* 2009 – A street in Wieliczka was named in his honour

* 2011 – An interactive Google logo inspired by ''The Cyberiad

''The Cyberiad'' ( pl, Cyberiada) is a series of humorous science fiction short stories by Polish writer Stanisław Lem, originally published in 1965, with an English translation appearing in 1974. The main protagonists of the series are Trurl a ...

'' was created and published in his honor for the 60th anniversary of his first published book: ''The Astronauts

''The Astronauts'' ( Polish: ''Astronauci'') is the first science fiction novel by Polish writer Stanisław Lem published as a book, in 1951.

To write the novel, Lem received advance payment from publishing house Czytelnik (Warsaw). The book b ...

''.

* 2013 – two planetoid

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''minor ...

s were named after Lem's literary characters:

** 343000 Ijontichy, after Ijon Tichy Ijon Tichy (Polish pronunciation: ) is a fictional character who appears in several works of the Polish science fiction writer Stanisław Lem: initially in '' The Star Diaries'', later in '' The Futurological Congress'', '' Peace on Earth'', '' Obse ...

** 343444 Halluzinelle, after Tichy's holographic companion Halluzinelle from German TV series '' Ijon Tichy: Space Pilot''

** Lem (satellite), a Polish optical astronomy satellite launched in 2013 as part of the Bright-star Target Explorer (BRITE) programme

* 2015: Pirx (crater)

Pirx is a 90 km (55.9 miles) wide impact crater on Pluto's natural satellite Charon, discovered in 2015 by the American New Horizons probe. It is located in at . The crater is located near Charon's north pole.

Crater Pirx is named after Pilot ...

, a90 km (55.9 miles) wide impact crater

An impact crater is a circular depression in the surface of a solid astronomical object formed by the hypervelocity impact of a smaller object. In contrast to volcanic craters, which result from explosion or internal collapse, impact crater ...

on Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

's natural satellite

A natural satellite is, in the most common usage, an astronomical body that orbits a planet, dwarf planet, or small Solar System body (or sometimes another natural satellite). Natural satellites are often colloquially referred to as ''moons'' ...

Charon

In Greek mythology, Charon or Kharon (; grc, Χάρων) is a psychopomp, the ferryman of Hades, the Greek underworld. He carries the souls of those who have been given funeral rites across the rivers Acheron and Styx, which separate the ...

, discovered in 2015 by the American New Horizons

''New Horizons'' is an interplanetary space probe that was launched as a part of NASA's New Frontiers program. Engineered by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) and the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), with a ...

probe

* 2019 – the star Solaris and its planet Pirx, after the novel '' Solaris'' and '' Tales of Pirx the Pilot''

* In December 2020 Polish Parliament declared year of 2021 to be the Year of Stanisław Lem.

* The Museum of City Engineering, Kraków, has the Stanislaw Lem Experience Garden, an outdoor area with over 70 interactive locations where children can carry out various physical experiments in acoustics, mechanics, hydrostatics and optics. Since 2011 the Garden has been organizing out the competition "Lemoniada", inspired by the creative output of Lem.

Political views

Lem's early works weresocialist realist

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is ...

, possibly to satisfy state censorship, and in his later years he was critical of this aspect of them. In 1982, with the onset of the martial law in Poland Lem moved to Berlin for studies and next year he moved for several years (1983–1988) to Vienna. However he never showed any wish to relocate permanently in the West. By the standards of the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

, Lem was financially well off for most of his life.

Lem was a critic of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

, totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regu ...

, and of both Stalinist and Western ideologies.

Lem believed there were no absolutes; "I should wish, as do most men, that immutable truths existed, that not all would be eroded by the impact of historical time, that there were some essential propositions, be it only in the field of human values, the basic values, etc. In brief, I long for the absolute. But at the same time I am firmly convinced that there are no absolutes, that everything is historical, and that you cannot get away from history."

Lem was concerned that if the human race attained prosperity and comfort this would lead it to passiveness and degeneration.

Personal life

Lem was a

Lem was a polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. More than half of all Eu ...

: he knew Polish, Latin (from medical school), German, French, English, Russian and Ukrainian.Tomasz Lem, ''Awantury na tle powszechnego ciążenia'', Kraków, Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2009, , p. 198. Lem claimed that his IQ was tested at high school as 180.

Lem was married to Barbara (née Leśniak) Lem until his death. She died on 27 April 2016. Their only son, , was born in 1968. He studied physics and mathematics at the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich hi ...

, and graduated with a degree in physics from Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

. Tomasz wrote a memoir about his father, ''Awantury na tle powszechnego ciążenia'' (''Tantrums on the Background of the Universal Gravitation''), which contain numerous personal details about Stanisław Lem. The book jacket says Tomasz works as a translator and has a daughter, Anna.

As of 1984, Lem's writing pattern was to get up a short time before five in the morning and start writing soon after, for 5 or 6 hours before taking a break.

Lem was an aggressive driver. He loved sweets (especially halva

Halva (also halvah, halwa, and other spellings, Persian : حلوا) is a type of confectionery originating from Persia and widely spread throughout the Middle East. The name is used for a broad variety of recipes, generally a thick paste made f ...

and chocolate-covered marzipan

Marzipan is a confection consisting primarily of sugar, honey, and almond meal (ground almonds), sometimes augmented with almond oil or extract.

It is often made into sweets; common uses are chocolate-covered marzipan and small marzipan imit ...

), and did not give them up even when, toward the end of his life, he fell ill with diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

. In the mid-80s due to health problems he stopped smoking. Coffee often featured in Lem's writing and interviews.

Stanisław Lem died from a heart failure in the hospital of the Jagiellonian University Medical College, Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

on 27 March 2006 at the age of 84. He was buried at Salwator Cemetery, Sector W, Row 4, grave 17 ( pl, cmentarz Salwatorski, sektor W, rząd 4, grób 17).

In November 2021, Agnieszka Gajewska's biography of Lem, ''Holocaust and the Stars'', was translated into English by Katarzyna Gucio and published by Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law ...

. It discussed aspects of Lem's life, such as being forced to wear the six-pointed badge and being struck for not removing his hat in the presence of Germans, as required of Jews at the time.

Lem loved movies and greatly enjoyed artistic cinema (especially the movies of Luis Buñuel

Luis Buñuel Portolés (; 22 February 1900 – 29 July 1983) was a Spanish-Mexican filmmaker who worked in France, Mexico, and Spain. He has been widely considered by many film critics, historians, and directors to be one of the greatest and ...

. He also liked the King Kong

King Kong is a fictional giant monster resembling a gorilla, who has appeared in various media since 1933. He has been dubbed The Eighth Wonder of the World, a phrase commonly used within the franchise. His first appearance was in the novelizat ...

, James Bond

The ''James Bond'' series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors hav ...

, Star Wars

''Star Wars'' is an American epic space opera multimedia franchise created by George Lucas, which began with the eponymous 1977 film and quickly became a worldwide pop-culture phenomenon. The franchise has been expanded into various film ...

and Star Trek

''Star Trek'' is an American science fiction media franchise created by Gene Roddenberry, which began with the eponymous 1960s television series and quickly became a worldwide pop-culture phenomenon. The franchise has expanded into vari ...

movies but he remained mostly displeased by movies which were based upon his own stories. The only notable exceptions are ''Voyage to the End of the Universe

''Ikarie XB-1'' is a 1963 Czechoslovak science fiction film directed by Jindřich Polák. It is based loosely on the novel '' The Magellanic Cloud'', by Stanisław Lem. The film was released in the United States, edited and dubbed into Englis ...

'' (1963) (which didn't credit Lem as writer of the original book " The Magellanic Cloud") and Layer Cake

A layer cake (US English) or sandwich cake (UK English) is a cake consisting of multiple stacked sheets of cake, held together by frosting or another type of filling, such as jam or other preserves. Most cake recipes can be adapted for lay ...

(1968) (which was based upon his short story "Do You Exist, Mr Jones?").

Bibliography

A list of books and monographs about Stanisław Lem:Notes

General references

Further reading

* Jameson, Fredric. "The Unknowability Thesis." In ''Archaeologies of the Future: This Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions.'' London and New York: Verso, 2005. * Suvin, Darko. "Three World Paradigms for SF: Asimov, Yefremov, Lem." ''Pacific Quarterly (Moana): An International Review of Arts and Ideas'' 4.(1979): 271–283.External links

* , maintained by Lem's son and secretary *forum.lem.pl

internet forum about Lem and his works *

Lemopedia, The Lem Encyclopedia

wiki * * *

Stanisław Lem: Did the Holocaust Shape His Sci-Fi World?

from Culture.pl {{DEFAULTSORT:Lem, Stanislaw 1921 births 2006 deaths 20th-century atheists 20th-century essayists 20th-century Polish Jews 20th-century Polish non-fiction writers 20th-century Polish novelists 20th-century Polish philosophers 20th-century Polish writers 20th-century scholars 20th-century short story writers 21st-century atheists 21st-century essayists 21st-century Polish Jews 21st-century Polish non-fiction writers 21st-century Polish novelists 21st-century Polish philosophers 21st-century Polish writers 21st-century scholars 21st-century short story writers Anti-capitalists Artificial intelligence ethicists Artificial intelligence researchers Atheist philosophers Burials at Salwator Cemetery Communication theorists Crime fiction writers Cultural critics Futurologists Hyperreality theorists Independent scholars Jagiellonian University alumni Jewish atheists Jewish humorists Jewish non-fiction writers Jewish philosophers Jewish Polish writers Literacy and society theorists Literary theorists Mass media theorists Neologists People from Lwów Voivodeship People with diabetes Philosophers of science Philosophers of social science Philosophers of technology Polish atheists Polish essayists Polish humorists Polish literary critics Polish male non-fiction writers Polish male writers Polish philosophers Polish satirists Polish sceptics Polish science fiction writers Polish speculative fiction critics Princeton University alumni Psychological fiction writers Recipients of the Order of Polonia Restituta (1944–1989) Recipients of the Order of the Banner of Work Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) Science fiction critics Science fiction fans Social commentators Social critics Social philosophers Surrealist writers Theorists on Western civilization University of Lviv alumni Writers about communism Writers about religion and science Writers from Kraków Writers from Lviv