Spanish architecture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spanish architecture refers to

Spanish architecture refers to

In the

In the

The Roman conquest, started in 218 BC, promoted the almost complete

The Roman conquest, started in 218 BC, promoted the almost complete

Roman

Roman  Ludic architecture is represented by such buildings as the theatres of Mérida,

Ludic architecture is represented by such buildings as the theatres of Mérida,

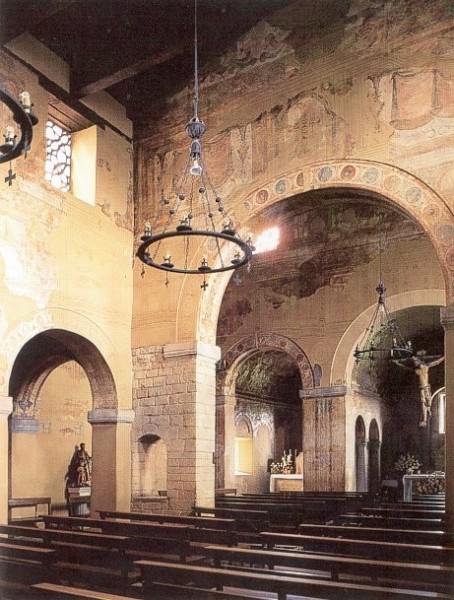

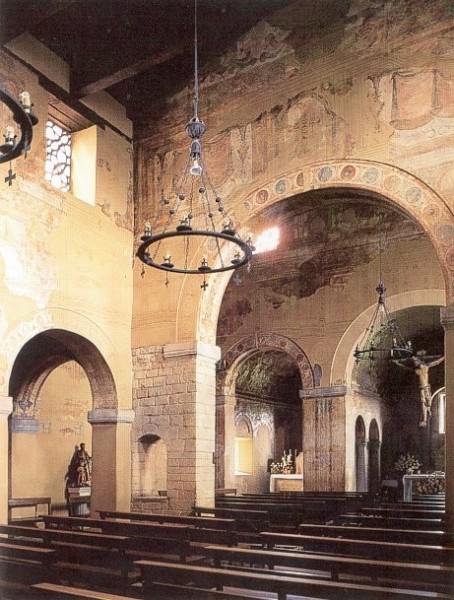

Cabeza de Griego

basilica, in Cuenca and the small church of San Cugat del Vallés, in

The

The  As regards its evolution, from its appearance, Asturian Pre-Romanesque followed a "stylistic sequence closely associated with the kingdom's political evolution, its stages clearly outlined". It was mainly a

As regards its evolution, from its appearance, Asturian Pre-Romanesque followed a "stylistic sequence closely associated with the kingdom's political evolution, its stages clearly outlined". It was mainly a

The Muslim conquest of the former

The Muslim conquest of the former

The Caliphate disappeared and was split into several small kingdoms called ''taifas''. During this period, art and culture continued to flourish despite the political fragmentation of Al-Andalus. The Aljaferia Palace of Zaragoza is the most significant palace preserved from this period, featuring complex ornamental arcades, multifoil and mixtilinear arches, and

The Caliphate disappeared and was split into several small kingdoms called ''taifas''. During this period, art and culture continued to flourish despite the political fragmentation of Al-Andalus. The Aljaferia Palace of Zaragoza is the most significant palace preserved from this period, featuring complex ornamental arcades, multifoil and mixtilinear arches, and

The late 11th century saw the significant advance of Christian kingdoms into Muslim al-Andalus, particularly with the fall of Toledo to

The late 11th century saw the significant advance of Christian kingdoms into Muslim al-Andalus, particularly with the fall of Toledo to

As the Almohad authority retreated from al-Andalus in the early 13th century, the Christian kingdoms of the north advanced again and Muslim al-Andalus was eventually reduced to the much smaller Nasrid Emirate centered in Granada, where much of the Muslim population took refuge. The palaces of the

As the Almohad authority retreated from al-Andalus in the early 13th century, the Christian kingdoms of the north advanced again and Muslim al-Andalus was eventually reduced to the much smaller Nasrid Emirate centered in Granada, where much of the Muslim population took refuge. The palaces of the

Romanesque architecture first developed in Spain in the 10th and 11th centuries, before

Romanesque architecture first developed in Spain in the 10th and 11th centuries, before

The Gothic style arrived in Spain in the 12th century. In this time, late Romanesque alternated with a few expressions of pure

The Gothic style arrived in Spain in the 12th century. In this time, late Romanesque alternated with a few expressions of pure

Mudéjar art influenced Christian architecture through Islamic and Jewish constructive and decorative methods and was highly variable from region to region. Mudéjar is characterised by the use of

Mudéjar art influenced Christian architecture through Islamic and Jewish constructive and decorative methods and was highly variable from region to region. Mudéjar is characterised by the use of

In Spain, Renaissance styles began to be grafted onto Gothic forms in the last decades of the 15th century. The forms that started to spread were made mainly by local architects: that is the cause of the creation of a specifically

In Spain, Renaissance styles began to be grafted onto Gothic forms in the last decades of the 15th century. The forms that started to spread were made mainly by local architects: that is the cause of the creation of a specifically  As decades passed, the Gothic influence disappeared and the research of an orthodox classicism reached high levels. Although Plateresque is a commonly used term to define most of the architectural production of the late 15th and first half of 16th century, some architects acquired a more sober personal style, like Diego Siloe and

As decades passed, the Gothic influence disappeared and the research of an orthodox classicism reached high levels. Although Plateresque is a commonly used term to define most of the architectural production of the late 15th and first half of 16th century, some architects acquired a more sober personal style, like Diego Siloe and

As Italian Baroque influences grew, they gradually superseded in popularity the restrained classicizing approach of Juan de Herrera, which had been in vogue since the late sixteenth century. As early as 1667, the façades of Granada Cathedral (by

As Italian Baroque influences grew, they gradually superseded in popularity the restrained classicizing approach of Juan de Herrera, which had been in vogue since the late sixteenth century. As early as 1667, the façades of Granada Cathedral (by

Spanish architecture refers to

Spanish architecture refers to architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

in any area of what is now Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, and by Spanish architects worldwide. The term includes buildings which were constructed within the current borders of Spain prior to its existence as a nation, when the land was called Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese language, Aragonese and Occitan language, Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a pe ...

, Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

, or was divided between several Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

and Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

kingdoms. Spanish architecture demonstrates great historical and geographical diversity, depending on the historical period. It developed along similar lines as other architectural styles around the Mediterranean and from Central and Northern Europe, although some Spanish constructions are unique.

A real development came with the arrival of the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, who left behind some of their most outstanding monuments in Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

. The arrival of the Visigoth

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kn ...

s brought about a profound decline in building techniques which was paralleled in the rest of the former Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. The Muslim conquest in 711 CE led to a radical change and for the following eight centuries there were great advances in culture, including architecture. For example, Córdoba was established as the cultural capital of its time under the Umayyad dynasty

Umayyad dynasty ( ar, بَنُو أُمَيَّةَ, Banū Umayya, Sons of Umayya) or Umayyads ( ar, الأمويون, al-Umawiyyūn) were the ruling family of the Caliphate between 661 and 750 and later of Al-Andalus between 756 and 1031. In the ...

. Simultaneously, Christian kingdoms such as Castile and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

gradually emerged and developed their own styles, at first mostly isolated from other European architectural influences, and soon later integrated into Romanesque and Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

and Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

streams, they reached an extraordinary peak with numerous samples along the whole territory. There were also some samples of Mudéjar

Mudéjar ( , also , , ca, mudèjar , ; from ar, مدجن, mudajjan, subjugated; tamed; domesticated) refers to the group of Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period despite the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for M ...

style, from the 12th to 16th centuries, characterised by the blending of Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance architectural styles with constructive, ornamental, and decorative motifs derived from those that had been brought to or developed in Al-Andalus.

Towards the end of the 15th century, and before influencing Latin America with its Colonial architecture

Colonial architecture is an architectural style from a mother country that has been incorporated into the buildings of settlements or colonies in distant locations. Colonists frequently built settlements that synthesized the architecture of their ...

, Spain itself experimented with Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture is the European architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 16th centuries in different regions, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of ancient Greek and Roman thought ...

, developed mostly by local architects. Spanish Baroque The arts of the Spanish Baroque include:

*Spanish Baroque painting

*Spanish Baroque architecture

** Spanish Baroque ephemeral architecture

*Spanish Baroque literature

**''Culteranismo''

**''Conceptismo''

* Spanish Baroque art

** Bodegón

**Tenebri ...

was distinguished by its exuberant Churrigueresque decoration and the most sober Herrerian style, both developing separately from later international influences. The Colonial style, which has lasted for centuries, still has a strong influence in Latin America. Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism ...

reached its peak in the work of Juan de Villanueva

Juan de Villanueva (September 15, 1739 in Madrid – August 22, 1811) was a Spanish architect. Alongside Ventura Rodríguez, Villanueva is the best known architect of Spanish Neoclassicism.

Biography

His father was the sculptor Juan de Villa ...

and his disciples.

The 19th century had two faces: the engineering efforts to achieve a new language and bring about structural improvements using iron and glass as the main building materials, and the academic focus, firstly on revivals and eclecticism

Eclecticism is a conceptual approach that does not hold rigidly to a single paradigm or set of assumptions, but instead draws upon multiple theories, styles, or ideas to gain complementary insights into a subject, or applies different theories i ...

, and later on regionalism. The arrival of Modernisme

''Modernisme'' (, Catalan for "modernism"), also known as Catalan modernism and Catalan art nouveau, is the historiographic denomination given to an art and literature movement associated with the search of a new entitlement of Catalan cultur ...

in the academic arena produced figures such as Gaudí and much of the architecture of the 20th century. The International style was led by groups like GATEPAC. Spain is currently experiencing a revolution in contemporary architecture

Contemporary architecture is the architecture of the 21st century. No single style is dominant. Contemporary architects work in several different styles, from postmodernism, high-tech architecture and new interpretations of traditional architec ...

and Spanish architects like Rafael Moneo, Santiago Calatrava

Santiago Calatrava Valls (born 28 July 1951) is a Spanish architect, structural engineer, sculptor and painter, particularly known for his bridges supported by single leaning pylons, and his railway stations, stadiums, and museums, whose sculp ...

, Ricardo Bofill

Ricardo Bofill Leví (; 5 December 1939 – 14 January 2022) was a Spanish architect from Catalonia. He founded Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura in 1963 and developed it into a leading international architectural and urban design practice. ...

as well as many others have gained worldwide renown.

Many architectural sites in Spain, and even portions of cities, have been designated World Heritage sites

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

by UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

. Spain has the third highest number of World Heritage Sites in the world; only Italy and China have more. These are listed at List of World Heritage Sites in Europe: Spain.

Prehistory

Megalithic architecture

In the

In the Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with ...

, the most common megalith found in the Iberian Peninsula was the dolmen

A dolmen () or portal tomb is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the early Neolithic (40003000 BCE) and were some ...

. The plans of these funerary chambers used to be pseudocircles or trapezoid

A quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel sides is called a trapezoid () in American and Canadian English. In British and other forms of English, it is called a trapezium ().

A trapezoid is necessarily a convex quadrilateral in Eu ...

s, formed by huge stones stuck on the ground, and others over them, forming the roof. As the typology

Typology is the study of types or the systematic classification of the types of something according to their common characteristics. Typology is the act of finding, counting and classification facts with the help of eyes, other senses and logic. Ty ...

evolved, an entrance corridor appeared, and gradually took prominence and became almost as wide as the chamber. Roofed corridors and false dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

s were common in the most advanced stage. The complex of Antequera

Antequera () is a city and municipality in the Comarca de Antequera, province of Málaga, part of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia. It is known as "the heart of Andalusia" (''el corazón de Andalucía'') because of its central loca ...

contains the largest dolmens in Europe. The best preserved, the Cueva de Menga, is twenty-five metres deep and four metres high, and was built with thirty-two megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

s.

The best preserved examples of architecture from the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

are located in the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

, where three kinds of construction appeared: the T-shaped taula

A taula (meaning 'table' in Catalan) is a Stonehenge-esque stone monument found on the Balearic island of Menorca. Taulas can be up to 5 metres high and consist of a vertical pillar (a monolith or several smaller stones on top of each other) w ...

, the talayot and the naveta {{No footnotes, date=April 2022

A naveta is a form of megalithic chamber tomb unique to the Balearic island of Menorca. They date to the early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 ...

. The talayots were troncoconical or troncopiramidal defensive towers. They used to have a central pillar. The navetas, were constructions made of great stones and their shape was similar to a ship hull.

Iberian and Celtic architecture

The most characteristic constructions of the Celts were the castros, walled villages usually on the top of hills or mountains. They were developed at the areas occupied by the Celts in theDouro valley

The Comunidade Intermunicipal do Douro () is an administrative division in Portugal. It replaced the ''Comunidade Urbana do Douro'', created in 2004. It takes its name from the Douro River. The seat of the intermunicipal community is Vila Real. D ...

(Portugal) and in Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

. Examples include Las Cogotas, in Ávila

Ávila (, , ) is a city of Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Ávila.

It lies on the right bank of the Adaja river. Located more than 1,130 m ab ...

, the Castro of Santa Tecla, in Pontevedra

Pontevedra (, ) is a Spanish city in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula. It is the capital of both the '' Comarca'' (County) and Province of Pontevedra, and of the Rías Baixas in Galicia. It is also the capital of its own municipality wh ...

in Spain.

The houses inside the castros are about 3.5 to 5 meters long, mostly circular with some rectangular, stone-made and with thatch roofs which rested on a wood column in the centre of the building. Their streets are somewhat regular, suggesting some form of central organization.

The towns built by the Arévacos were related to Iberian culture, and some of them reached notable urban development like Numantia

Numantia ( es, Numancia) is an ancient Celtiberian settlement, whose remains are located on a hill known as Cerro de la Muela in the current municipality of Garray ( Soria), Spain.

Numantia is famous for its role in the Celtiberian Wars. In ...

. Others were more primitive and usually excavated into the rock, like Termantia

Termantia, the present-day locality of Tiermes, is an archaeological site on the edge of the Duero valley in Spain. It is located in the sparsely populated ''municipio'' of Montejo de Tiermes (Soria, Castile and León).

During the Iron Age it w ...

.

Roman

Urban development

The Roman conquest, started in 218 BC, promoted the almost complete

The Roman conquest, started in 218 BC, promoted the almost complete romanization

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, a ...

of the Iberian Peninsula. Roman culture was fully assimilated by the local population. Former military camps and Iberian, Phoenician and Greek settlements were transformed into large cities where urbanization highly developed in the provinces; Augusta Emerita in the Lusitania

Lusitania (; ) was an ancient Iberian Roman province located where modern Portugal (south of the Douro river) and

a portion of western Spain (the present Extremadura and the province of Salamanca) lie. It was named after the Lusitani or Lu ...

, Corduba, Italica, Hispalis, Gades in the Hispania Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula). Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Hispania Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of the basic di ...

, Tarraco

Tarraco is the ancient name of the current city of Tarragona (Catalonia, Spain). It was the oldest Roman settlement on the Iberian Peninsula. It became the capital of the Roman province of Hispania Citerior during the period of the Roman Republi ...

, Caesar Augusta, Asturica Augusta, Legio Septima Gemina and Lucus Augusti in the Hispania Tarraconensis

Hispania Tarraconensis was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania. It encompassed much of the northern, eastern and central territories of modern Spain along with modern northern Portugal. Southern Spain, the region now called Andalusia was the ...

were some of the most important cities, linked by a complex network of roads. The construction development includes some monuments of comparable quality to those of the capital, Rome.

Constructions

Roman

Roman civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewa ...

is represented in imposing constructions such as the Aqueduct of Segovia

The Aqueduct of Segovia () is a Roman aqueduct in Segovia, Spain. It was built around the first century AD to channel water from springs in the mountains away to the city's fountains, public baths and private houses, and was in use until 1973. I ...

and the Acueducto de los Milagros in Mérida, in bridges like the Alcántara Bridge

The Alcántara Bridge (also known as Trajan's Bridge at Alcantara) is a Roman bridge at Alcántara, in Extremadura, Spain. Alcántara is from the Arabic word ''al-Qantarah'' (القنطرة) meaning "the arch". The stone arch bridge was bui ...

, Puente Romano Puente, a word meaning '' bridge'' in Spanish language, may refer to:

People

* Puente (surname)

Places

*La Puente, California, USA

* Puente Alto, city and commune of Chile

*Puente de Ixtla, city in Mexico

*Puente Genil, village in the Spanish pro ...

over Guadiana

The Guadiana River (, also , , ), or Odiana, is an international river defining a long stretch of the Portugal-Spain border, separating Extremadura and Andalusia (Spain) from Alentejo and Algarve (Portugal). The river's basin extends from the e ...

River, and the Roman bridge of Córdoba

The Roman bridge of Córdoba is a bridge in the Historic centre of Córdoba, Andalusia, southern Spain, originally built in the early 1st century BC across the Guadalquivir river, though it has been reconstructed at various times since. It is a ...

over the Guadalquivir

The Guadalquivir (, also , , ) is the fifth-longest river in the Iberian Peninsula and the second-longest river with its entire length in Spain. The Guadalquivir is the only major navigable river in Spain. Currently it is navigable from the Gul ...

. Civil works were widely developed in Hispania under Emperor Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

(98-117 AD). Lighthouses

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses mar ...

like the one still in use Hercules Tower in A Coruña

A Coruña (; es, La Coruña ; historical English: Corunna or The Groyne) is a city and municipality of Galicia, Spain. A Coruña is the most populated city in Galicia and the second most populated municipality in the autonomous community and ...

, were also built.

Ludic architecture is represented by such buildings as the theatres of Mérida,

Ludic architecture is represented by such buildings as the theatres of Mérida, Sagunto

Sagunto ( ca-valencia, Sagunt) is a municipality of Spain, located in the province of Valencia, Valencian Community. It belongs to the modern fertile ''comarca'' of Camp de Morvedre. It is located c. 30 km north of the city of Valencia, ...

, Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

, Cartagena, and Tarraco

Tarraco is the ancient name of the current city of Tarragona (Catalonia, Spain). It was the oldest Roman settlement on the Iberian Peninsula. It became the capital of the Roman province of Hispania Citerior during the period of the Roman Republi ...

, amphitheaters in Mérida, Italica, Tarraco

Tarraco is the ancient name of the current city of Tarragona (Catalonia, Spain). It was the oldest Roman settlement on the Iberian Peninsula. It became the capital of the Roman province of Hispania Citerior during the period of the Roman Republi ...

or Segóbriga

Segóbriga was an important Celtic and Roman city, and is today an impressive site located on a hill (cerro Cabeza de Griego) near the present town of Saelices.

Research has revealed remains of important buildings, which have since been preserve ...

, and circuses in Mérida, Toledo, and many others.

Religious architecture also spread thougout the Peninsula; examples include the Roman temples of Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, Córdoba, Vic, and Alcántara

Alcántara is a municipality in the province of Cáceres, Extremadura, Spain, on the Tagus, near Portugal. The toponym is from the Arabic word ''al-Qanṭarah'' (القنطرة) meaning "the bridge".

History

Archaeological findings have atteste ...

,

The main funerary monuments are the Torre dels Escipions in Tarraco, the distyle

A distyle is a small temple-like structure with two columns. By extension, a distyle can also mean a distyle in antis, the original design of the Greek temple, where two columns are set between two antae.

See also

* Prostyle

*Amphiprostyle

In ...

in Zalamea de la Serena, and the Mausoleum of the Atilii in Sádaba, Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Province of Zaragoza, Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Ara ...

. Roman triumphal arches can be found in Cabanes, Castellón, Medinaceli

Medinaceli () is a municipality and town in the province of Soria, in Castile and León, Spain. The municipality includes other villages like Torralba del Moral.

Etymology

Its name derives from the Arabic 'madīnat salīm', which was named aft ...

, and the Arc de Berà near Roda de Berà.

Pre-Romanesque

The term Pre-Romanesque refers to the Christian art after the Classical Age and beforeRomanesque art

Romanesque art is the art of Europe from approximately 1000 AD to the rise of the Gothic Art, Gothic style in the 12th century, or later depending on region. The preceding period is known as the Pre-Romanesque period. The term was invented by 1 ...

and architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

. It covers very heterogeneous artistic displays for they were developed in different centuries and by different cultures. Spanish territory boasts a rich variety of Pre-Romanesque architecture: some of its branches, like the Asturian art

Pre-Romanesque architecture in Asturias is framed between the years 711 and 910, the period of the creation and expansion of the kingdom of Asturias.

History

In the 5th century, the Goths, a Christianized tribe of Eastern Germanic origin, arrived ...

reached high levels of refinement for their era and cultural context.

Visigothic architecture

From the6th century

The 6th century is the period from 501 through 600 in line with the Julian calendar. In the West, the century marks the end of Classical Antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages. The collapse of the Western Roman Empire late in the previous ...

, it is worth mentioning the remains of thCabeza de Griego

basilica, in Cuenca and the small church of San Cugat del Vallés, in

Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

. This one, although very deteriorated, clearly shows a single nave plan that ends in an apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

. From the following century are those of San Pedro de la Nave, San Juan de Baños, Santa María de Quintanilla de las Viñas, whose layout will later be repeated in other later temples belonging to the " repopulation style" (misnamed "Mozarab

The Mozarabs ( es, mozárabes ; pt, moçárabes ; ca, mossàrabs ; from ar, مستعرب, musta‘rab, lit=Arabized) is a modern historical term for the Iberian Christians, including Christianized Iberian Jews, who lived under Muslim rule in A ...

»). For the rest, at this time the early Christian tradition is basically followed in religious architecture. The most representative buildings can be related to the following:

Church of San Pedro de la Nave in San Pedro de la Nave-Almendra ( Zamora)

Church of Santa Comba de Bande ( Orense)

Church of San Juan Bautista de Baños de Cerrato ( Palencia)

Crypt of San Antolín in the cathedral of Palencia ( Palencia)

Church of San Pedro de la Mata de Sonseca ( Toledo)

Chapel of Santa María de Quintanilla de las Viñas (Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence o ...

)

Asturian architecture

The

The kingdom of Asturias

The Kingdom of Asturias ( la, Asturum Regnum; ast, Reinu d'Asturies) was a kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula founded by the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius. It was the first Christian political entity established after the Umayyad conquest of ...

arose in 718, when the Astur tribes, rallied in assembly, decided to appoint Pelayo as their leader. Pelayo joined the local tribes and the refuged Visigoths under his command, with the intention of progressively restoring Gothic Order.

Asturian Pre-Romanesque is a singular feature in all Spain, which, while combining elements from other styles as Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

and local traditions, created and developed its own personality and characteristics, reaching a considerable level of refinement, not only as regards construction, but also in terms of aesthetics.

As regards its evolution, from its appearance, Asturian Pre-Romanesque followed a "stylistic sequence closely associated with the kingdom's political evolution, its stages clearly outlined". It was mainly a

As regards its evolution, from its appearance, Asturian Pre-Romanesque followed a "stylistic sequence closely associated with the kingdom's political evolution, its stages clearly outlined". It was mainly a court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in acco ...

architecture, and five stages are distinguished: a first period (737–791) from the reign of the king Fáfila to Vermudo I, a second stage comprises the reign of Alfonso II (791–842), entering a stage of stylistic definition. These two first stages receive the name of 'Pre-Ramirense'. The most important example is the church San Julián de los Prados

San Julián de los Prados, also known as Santullano, is a Pre-Ramirense church from the beginning of the 9th century in Oviedo, the capital city of the Principality of Asturias, Spain. It is one of the greatest works of Asturian art and was dec ...

in Oviedo

Oviedo (; ast, Uviéu ) is the capital city of the Principality of Asturias in northern Spain and the administrative and commercial centre of the region. It is also the name of the municipality that contains the city. Oviedo is located a ...

, with an interesting volume system and a complex iconographic fresco program, related narrowly to the Roman mural paintings. Lattices and trifoliate windows in the apse appear for the first time at this stage. The Holy Chamber of the Cathedral of Oviedo

The Metropolitan Cathedral Basilica of the Holy Saviour or Cathedral of San Salvador ( es, Catedral Metropolitana Basílica de San Salvador, la, Sancta Ovetensis) is a Roman Catholic church and minor basilica in the centre of Oviedo, in the Ast ...

, San Pedro de Nora and Santa María de Bendones also belong to it.

The third period comprises the reigns of Ramiro I (842–850) and Ordoño I (850–866). It is called 'Ramirense' and is considered the zenith of the style, due to the work of an unknown architect who brought new structural and ornamental achievements like the barrel vault

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

, and the consistent use of transverse arches and buttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient buildings, as a means of providing support to act against the lateral (s ...

es, which made the style rather close to the structural achievements of the Romanesque two centuries later. Some writers have pointed to an unexplained Syrian influence of the rich ornamentation. In that period, most of the masterpieces of the style flourished: the palace pavilions of Naranco Mountain (Santa Maria del Naranco

Santa Claus, also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Kris Kringle, or simply Santa, is a legendary figure originating in Western Christian culture who is said to bring children gifts during the late evening and overnigh ...

and San Miguel de Lillo

St. Michael of Lillo ( es, San Miguel de Lillo, ast, Samiguel de Lliño) is a Roman Catholic church built on the Naranco mount, near the Church of Santa María del Naranco in Asturias. It was completed in 842 and it was consecrated by Ramir ...

), and the church of Santa Cristina de Lena

St Christine of Lena ( es, Santa Cristina de Lena) is a Roman Catholic Asturian pre-Romanesque church located in the Lena municipality, about 25 km south of Oviedo, Spain, on an old Roman road that joined the lands of the plateau with Ast ...

were built in that period.

The fourth period belongs to the reign of Alfonso III (866–910), where a strong Mozarabic

Mozarabic, also called Andalusi Romance, refers to the medieval Romance varieties spoken in the Iberian Peninsula in territories controlled by the Islamic Emirate of Córdoba and its successors. They were the common tongue for the majority of ...

influence arrived to Asturian architecture, and the use of the horseshoe arch

The horseshoe arch (; Spanish: "arco de herradura"), also called the Moorish arch and the keyhole arch, is an emblematic arch of Islamic architecture, especially Moorish architecture. Horseshoe arches can take rounded, pointed or lobed form.

Hi ...

expanded. A fifth and last period, which coincides with the transfer of the court to León, the disappearance of the kingdom of Asturias, and simultaneously, of Asturian Pre-Romanesque.

Mozarabic architecture

Mozarabic architecture was carried out by theMozarabs

The Mozarabs ( es, mozárabes ; pt, moçárabes ; ca, mossàrabs ; from ar, مستعرب, musta‘rab, lit=Arabized) is a modern historical term for the Iberian Christians, including Christianized Iberian Jews, who lived under Muslim rule in A ...

, Christians who lived in Muslim Spain from the Arab invasion (711 711 may refer to:

* 711 (number), a natural number

* AD 711, a year of the 8th century AD

* 711 BC, a year of the 8th century BC

* 7-1-1, the telephone number of the Telecommunications Relay Service in the United States and Canada

* 7-Eleven, a c ...

) until the end of the 11th century

The 11th century is the period from 1001 ( MI) through 1100 ( MC) in accordance with the Julian calendar, and the 1st century of the 2nd millennium.

In the history of Europe, this period is considered the early part of the High Middle Ages. ...

, and who maintained their distinct personality also against the Christians of the northern kingdoms, to them that were emigrating in successive waves or being incorporated during the ''Reconquista

The ' ( Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the N ...

''. An example of this architecture is the church of Bobastro, a cave temple found in the place known as Mesas de Villaverde, in Ardales (Málaga), of which only a few ruins remain. Another representative building of this architecture is the church of Santa María de Melque, located in the vicinity of La Puebla de Montalbán ( Toledo). Regarding this temple, there is doubt in its stylistic affiliation, since it shares Visigoth features with others more properly Mozarabic, its dating being not clear either. The hermitage of San Baudelio de Berlanga presents an unprecedented typology, including in its rectangular plan a tribune over a small hypostyle hall, in the manner of mosques, and its roof is supported by a single central pillar shaped like a palm tree. Both this pillar and the interior walls are profusely decorated with frescoes depicting hunting scenes and exotic animals. A certain typological connection can be established as an initiatory temple, already in Romanesque times, with the church of Santa María de Eunate and other centralized Templar buildings, such as Torres del Río or Vera Cruz de Segovia.

Repopulation architecture

Between the end of the 9th century and the beginning of the 11th century, a number of churches were built in the Northern Christian kingdoms. They are widely but incorrectly known as Mozarabic architecture. This architecture is a summary of elements of diverse extraction irregularly distributed, of a form that in occasions predominate those of paleo-Christian, Visigothic or Asturian origin, while at other times emphasizes the Muslim impression. The churches have usually basilica or centralized plans, sometimes with opposing apses. Principal chapels are of rectangular plan on the exterior and ultra-semicircular in the interior. Thehorseshoe arch

The horseshoe arch (; Spanish: "arco de herradura"), also called the Moorish arch and the keyhole arch, is an emblematic arch of Islamic architecture, especially Moorish architecture. Horseshoe arches can take rounded, pointed or lobed form.

Hi ...

of Muslim evocation is used, somewhat more closed and sloped than the Visigothic as well as the alfiz The alfiz (, from Andalusi Arabic ''alḥíz'', from Standard Arabic ''alḥáyyiz'', meaning 'the container';Al ...

. Geminated and tripled windows of Asturian tradition and grouped columns forming composite pillars, with Corinthian capital decorated with stylized elements.

Decoration has resemblance to the Visigothic based in volutes, swastikas

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. It ...

, and vegetable and animal themes forming projected borders and sobriety of exterior decoration. Some innovations are introduced, as great lobed corbel

In architecture, a corbel is a structural piece of stone, wood or metal jutting from a wall to carry a superincumbent weight, a type of bracket. A corbel is a solid piece of material in the wall, whereas a console is a piece applied to the s ...

s that support very pronounced eaves

The eaves are the edges of the roof which overhang the face of a wall and, normally, project beyond the side of a building. The eaves form an overhang to throw water clear of the walls and may be highly decorated as part of an architectural styl ...

. A great command of the technique in construction can be observed, employing ashlar, walls reinforced by exterior buttresses and covering by means of segmented vaults, including by the traditional barrel vaults.

The architecture of Al-Andalus

Emirate and Caliphate of Córdoba

The Muslim conquest of the former

The Muslim conquest of the former Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

by the troops of Musa ibn Nusair and Tariq ibn Ziyad, and the overthrowing of the Umayyad dynasty

Umayyad dynasty ( ar, بَنُو أُمَيَّةَ, Banū Umayya, Sons of Umayya) or Umayyads ( ar, الأمويون, al-Umawiyyūn) were the ruling family of the Caliphate between 661 and 750 and later of Al-Andalus between 756 and 1031. In the ...

in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, eventually led to the creation of an independent emirate by Abd ar-Rahman I, the only surviving Umayyad prince who escaped from Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

, and established his capital city in Córdoba. It served as the capital of Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

from 750 to 1010, with its political and cultural apogee taking place during the new Caliphate period in the 10th century.

In Cordoba, Abd ar-Rahman I built the Great Mosque in 785. It was expanded multiple times up until the 10th century, and after the ''Reconquista'' it was converted into a Catholic cathedral. Its key features include a hypostyle

In architecture, a hypostyle () hall has a roof which is supported by columns.

Etymology

The term ''hypostyle'' comes from the ancient Greek ὑπόστυλος ''hypóstȳlos'' meaning "under columns" (where ὑπό ''hypó'' means below or un ...

hall with marble columns supporting two-tiered arches, a horseshoe-arch mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla ...

, ribbed domes, a courtyard (''sahn

A ''sahn'' ( ar, صَحْن, '), is a courtyard in Islamic architecture, especially the formal courtyard of a mosque. Most traditional mosques have a large central ''sahn'', which is surrounded by a '' riwaq'' or arcade on all sides. In traditi ...

'') with gardens, and a minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

(later converted into a bell tower

A bell tower is a tower that contains one or more bells, or that is designed to hold bells even if it has none. Such a tower commonly serves as part of a Christian church, and will contain church bells, but there are also many secular bell tow ...

). Abd ar-Rahman III, at the height of his power, began construction of Madinat al-Zahra

Madinat al-Zahra or Medina Azahara ( ar, مدينة الزهراء, translit=Madīnat az-Zahrā, lit=the radiant city) was a fortified palace-city on the western outskirts of Córdoba in present-day Spain. Its remains are a major archaeological ...

, a luxurious palace-city to serve as a new capital. It played a major role in formulating a more distinct "caliphal" style which was crucial in the development of subsequent Andalusi architecture. On a smaller scale, the Bab al-Mardum Mosque (later converted to a church) in Toledo is a well-preserved example of a small neighbourhood mosque built at the end of the Caliphate period.

The Taifas

The Caliphate disappeared and was split into several small kingdoms called ''taifas''. During this period, art and culture continued to flourish despite the political fragmentation of Al-Andalus. The Aljaferia Palace of Zaragoza is the most significant palace preserved from this period, featuring complex ornamental arcades, multifoil and mixtilinear arches, and

The Caliphate disappeared and was split into several small kingdoms called ''taifas''. During this period, art and culture continued to flourish despite the political fragmentation of Al-Andalus. The Aljaferia Palace of Zaragoza is the most significant palace preserved from this period, featuring complex ornamental arcades, multifoil and mixtilinear arches, and stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

decoration. In other cities, a number of important palaces or fortresses were begun or expanded by local dynasties such as the Alcazaba of Málaga

The Alcazaba ( ar, القصبة) is a palatial fortification in Málaga, Spain, built during the period of Muslim-ruled Al-Andalus. The current complex was begun in the 11th century and was modified or rebuilt multiple times up to the 14th centur ...

and the Alcazaba of Almería

The Alcazaba of Almería is a fortified complex in Almería, southern Spain. The word '' alcazaba'', from the Arabic word (; '' ''), signifies a walled fortification in a city.

History

In 955, Almería was given the title of ''medina'' ("city") ...

. Other examples of architecture from around this period include the Bañuelo of Granada, an Islamic bathhouse.

Almoravids and Almohads

Alfonso VI

Alphons (Latinized ''Alphonsus'', ''Adelphonsus'', or ''Adefonsus'') is a male given name recorded from the 8th century (Alfonso I of Asturias, r. 739–757) in the Christian successor states of the Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian peninsula. ...

of Castile in 1085, and the rise of major Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–19 ...

empires originating in present-day Morocco. The latter included first the Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that s ...

(11th–12th centuries) and then the Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire ...

(12th–13th centuries), both of whom created empires that stretched across large parts of western and northern Africa and took over the remaining Muslim territories of al-Andalus in Europe. This period is considered one of the most formative stages of western Islamic (or "Moorish") architecture, establishing many of the forms and motifs that were refined in subsequent centuries.

Relatively little survives of Almoravid architecture but much more has survived of Almohad architecture. In Seville, the Almohad rulers built a new Great Mosque (later transformed into the Cathedral of Seville

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See ( es, Catedral de Santa María de la Sede), better known as Seville Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Seville, Andalusia, Spain. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, alon ...

), which consisted of a hypostyle prayer hall, a courtyard (now known as the ''Patio de los Naranjos'' or Court of Oranges), and a massive minaret tower now known as the Giralda

The Giralda ( es, La Giralda ) is the bell tower of Seville Cathedral in Seville, Spain. It was built as the minaret for the Great Mosque of Seville in al-Andalus, Moorish Spain, during the reign of the Almohad dynasty, with a Renaissance-style ...

. The minaret was later expanded after being converted into a bell tower for the current cathedral. Other examples of Almohad architecture are found in various fortifications and smaller monuments in southern Spain today, as well as in traces of the former Almohad palace in the Alcazar of Seville. Almohad architecture promoted new forms and decorative designs such as the multifoil arch

A multifoil arch (or polyfoil arch), also known as a cusped arch, polylobed arch, or scalloped arch, is an arch characterized by multiple circular arcs or leaf shapes (called foils, lobes, or cusps) that are cut into its interior profile or intra ...

and the '' sebka'' motif, probably influenced by the Caliphate-period architecture of Cordoba.

Nasrid Emirate of Granada

As the Almohad authority retreated from al-Andalus in the early 13th century, the Christian kingdoms of the north advanced again and Muslim al-Andalus was eventually reduced to the much smaller Nasrid Emirate centered in Granada, where much of the Muslim population took refuge. The palaces of the

As the Almohad authority retreated from al-Andalus in the early 13th century, the Christian kingdoms of the north advanced again and Muslim al-Andalus was eventually reduced to the much smaller Nasrid Emirate centered in Granada, where much of the Muslim population took refuge. The palaces of the Alhambra

The Alhambra (, ; ar, الْحَمْرَاء, Al-Ḥamrāʾ, , ) is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Andalusia, Spain. It is one of the most famous monuments of Islamic architecture and one of the best-preserved palaces of ...

and the Generalife

The Generalife (; ar, جَنَّة الْعَرِيف, translit=Jannat al-‘Arīf) was a summer palace and country estate of the Nasrid rulers of the Emirate of Granada in Al-Andalus. It is located directly east of and uphill from the Alhambra ...

in Granada, built under the Nasrid dynasty

The Nasrid dynasty ( ar, بنو نصر ''banū Naṣr'' or ''banū al-Aḥmar''; Spanish: ''Nazarí'') was the last Muslim dynasty in the Iberian Peninsula, ruling the Emirate of Granada from 1230 until 1492. Its members claimed to be of Arab ...

, are the most iconic monuments of this period and reflect the last great period of art and architecture in al-Andalus before its final end. The Alhambra complex was begun by Ibn al-Ahmar, the first Nasrid emir, and the last major additions were made during the reigns of Yusuf I

Abu al-Hajjaj Yusuf ibn Ismail ( ar, أبو الحجاج يوسف بن إسماعيل; 29 June 131819 October 1354), known by the regnal name al-Muayyad billah (, "He who is aided by God"), was the seventh Nasrid ruler of the Emirate of Grana ...

(1333–1353) and Muhammad V Mohamed V may refer to:

* Al-Mu'tazz, sometimes referred to as ''Muhammad V'', was the Abbasid caliph (from 866 to 869).

* Muhammed V of Granada (1338–1391), Sultan of Granada

* Mehmed V (1848–1918), 39th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire

* Mohamm ...

(1353–1391).

Nasrid architecture continued the earlier traditions of Andalusi architecture while also synthesizing them into its own distinctive style, which had many similarities with the architecture of contemporary dynasties in North Africa such as the Marinids. It is characterized by the use of the courtyard as a central space and basic unit around which other halls and rooms were organized. Courtyards typically had water features at their center, such as a reflective pool or a fountain. Decoration was focused on the inside of buildings and was executed primarily with tile mosaics on lower walls and carved stucco on the upper walls. The multiplicity of decoration, the skillful use of light and shadow and the incorporation of water into the architecture are some of the keys features of the style. Geometric patterns, vegetal motifs, and calligraphy

Calligraphy (from el, link=y, καλλιγραφία) is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined ...

were the main types of decorative motifs, typically carved in wood and stucco or crafted with mosaic tilework known as ''zellij

''Zellij'' ( ar, الزليج, translit=zillīj; also spelled zillij or zellige) is a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled tile pieces. The pieces were typically of different colours and fitted together to form various pa ...

''. Additionally, "stalactite"-like sculpting, known as ''muqarnas

Muqarnas ( ar, مقرنص; fa, مقرنس), also known in Iranian architecture as Ahoopāy ( fa, آهوپای) and in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe, is a form of ornamented vaulting in Islamic architecture. It is the archetypal form of I ...

'', was used for three-dimensional features like vaulted ceilings, particularly during the reign of Muhammad V and after. Epigraphic inscriptions were carved on the walls of many rooms and included allusive poems to the beauty of the spaces.

Romanesque

Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in ...

's influence, in Lérida, Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, Tarragona

Tarragona (, ; Phoenician: ''Tarqon''; la, Tarraco) is a port city located in northeast Spain on the Costa Daurada by the Mediterranean Sea. Founded before the fifth century BC, it is the capital of the Province of Tarragona, and part of Tarr ...

and Huesca

Huesca (; an, Uesca) is a city in north-eastern Spain, within the autonomous community of Aragon. It is also the capital of the Spanish province of the same name and of the comarca of Hoya de Huesca. In 2009 it had a population of 52,059, almo ...

, and in the Pyrenees, simultaneously with the north of Italy, as what is called First Romanesque

One of the first streams of Romanesque architecture in Europe from the 10th century and the beginning of 11th century is called First Romanesque or Lombard Romanesque. It took place in the region of Lombardy (at that time the term encompassing ...

or Lombard Romanesque. It is a very primitive style, whose characteristics are thick walls, lack of sculpture and the presence of rhythmic ornamental arches, typified by the churches in the Valle de Bohí.

The full Romanesque architecture arrived with the influence of Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in ...

through the Way of Saint James, that ends in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. The model of the Spanish Romanesque in the 12th century was the Cathedral of Jaca

The Cathedral of St Peter the Apostle ( es, Catedral de San Pedro Apóstol) is a Roman Catholic church located in Jaca, in Aragon, Spain. It is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Jaca.

It is the first Romanesque cathedral built in Arag ...

, with its characteristic plan and apse, and its "chessboard" decoration in stripes, called ''taqueado jaqués''. As the Christian Kingdoms advanced southwards, this model spread throughout the reconquered areas with some variations. Spanish Romanesque also shows the influence of Spanish pre-Romanesque styles, mainly Asturian and Mozarabic, but there is also a strong Moorish influence, especially the vaults of Córdoba's Mosque, and the multifoil arch

A multifoil arch (or polyfoil arch), also known as a cusped arch, polylobed arch, or scalloped arch, is an arch characterized by multiple circular arcs or leaf shapes (called foils, lobes, or cusps) that are cut into its interior profile or intra ...

es. In the 13th century, some churches alternated in style between Romanesque and Gothic. Aragón

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises th ...

, Navarra

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spa ...

and Castile-Leon are some of the best areas for Spanish Romanesque architecture.

Gothic

The Gothic style arrived in Spain in the 12th century. In this time, late Romanesque alternated with a few expressions of pure

The Gothic style arrived in Spain in the 12th century. In this time, late Romanesque alternated with a few expressions of pure Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture (or pointed architecture) is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It ...

like the Cathedral of Ávila

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

. The High Gothic arrived in all its strength through the Way of St. James in the 13th century, with some of the purest Gothic cathedrals, with French and German influences: the cathedrals of Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence o ...

, León and Toledo.

The most important post-13th century Gothic styles in Spain are the Levantine and Isabelline Gothic. Levantine Gothic is characterised by its structural achievements and their unification of space, with masterpieces as La Seu in Palma de Mallorca

Palma (; ; also known as ''Palma de Mallorca'', officially between 1983–88, 2006–08, and 2012–16) is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands in Spain. It is situated on the south coast of Mallorca ...

; the Valencian Gothic

Valencian Gothic is an architectural style. It occurred under the Kingdom of Valencia between the 13th and 15th centuries, which places it at the end of the European Gothic period and at the beginning of the Renaissance. The term "Valencian ...

style of the Lonja de Valencia (Valencia's silk market), and Santa Maria del Mar (Barcelona).

Isabelline Gothic, created during the times of the Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bot ...

, was part of the transition to Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture is the European architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 16th centuries in different regions, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of ancient Greek and Roman thought ...

, but also a strong resistance to Italian Renaissance style. Highlights of the style include the Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo and the Royal Chapel of Granada

The Royal Chapel of Granada ( es, Capilla Real de Granada) is an Isabelline style building, constructed between 1505 and 1517, and originally integrated in the complex of the neighbouring Granada Cathedral. It is the burial place of the Spanish ...

.

Mudéjar

Mudéjar style or art is Christian architecture with Islamic influenced decoration that emerged in the Christian kingdoms of the north in the 12th century and spread with theChristian reconquest

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

of the Iberian Peninsula. The reconquest brought Moorish craftsmen under Christian rule who then influenced architecture in the expanding Christian kingdoms. It is not a style of architecture; ''Mudéjar style'' refers to the application of Moorish style decorations or materials to whatever Christian architecture existed at the time, producing Mudéjar-Romanesque, Mudéjar-Gothic and Mudéjar-Renaissance.

Mudéjar art influenced Christian architecture through Islamic and Jewish constructive and decorative methods and was highly variable from region to region. Mudéjar is characterised by the use of

Mudéjar art influenced Christian architecture through Islamic and Jewish constructive and decorative methods and was highly variable from region to region. Mudéjar is characterised by the use of brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

as the main building material. The dominant geometrical character, distinctly Islamic, emerged conspicuously in the accessory crafts using cheap materials elaborately worked – tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or ...

work, brickwork

Brickwork is masonry produced by a bricklayer, using bricks and mortar. Typically, rows of bricks called ''courses'' are laid on top of one another to build up a structure such as a brick wall.

Bricks may be differentiated from blocks by si ...

, wood carving

Wood carving is a form of woodworking by means of a cutting tool (knife) in one hand or a chisel by two hands or with one hand on a chisel and one hand on a mallet, resulting in a wooden figure or figurine, or in the sculptural ornamentati ...

, plaster carving, and ornamental metals. Even after the Muslims were no longer employed, many of their methods and decorative styles continued to be applied to Spanish architecture.

Mudéjar style was born in the northern town of Sahagún

Sahagún () is a town and municipality of Spain, part of the autonomous community of Castile and León and the province of León. It is the main populated place in the Leonese part of the Tierra de Campos natural region.

Sahagún contains some o ...

. It spread to the rest of the Kingdom of León

The Kingdom of León; es, Reino de León; gl, Reino de León; pt, Reino de Leão; la, Regnum Legionense; mwl, Reino de Lhion was an independent kingdom situated in the northwest region of the Iberian Peninsula. It was founded in 910 when t ...

; Toledo, Ávila, Segovia

Segovia ( , , ) is a city in the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the Province of Segovia.

Segovia is in the Inner Plateau ('' Meseta central''), near the northern slopes of t ...

, and later was spread to southern Spain by the Castile, especially Seville and Granada. However, the famous ''Mudéjar Rooms'' of the Alcázar of Seville

The Royal Alcázars of Seville ( es, Reales Alcázares de Sevilla), historically known as al-Qasr al-Muriq (, ''The Verdant Palace'') and commonly known as the Alcázar of Seville (), is a royal palace in Seville, Spain, built for the Christian ...

, although often classified as Mudéjar style, are actually closely related to the Moorish Nasrid palace architecture of the Alhambra; the Christian king, Pedro of Castile

Peter ( es, Pedro; 30 August 133423 March 1369), called the Cruel () or the Just (), was King of Castile and León from 1350 to 1369. Peter was the last ruler of the main branch of the House of Ivrea. He was excommunicated by Pope Urban V for ...

commissioned Moorish architects from Granada to build them. Centers of Mudéjar art are found in other cities Toro, Cuéllar

Cuéllar () is a municipality in the Province of Segovia, within the autonomous community of Castile and León, Spain.

The municipality had a population of 9,730 inhabitants according to the municipal register of inhabitants (INE) as of 1 Jan ...

, Arévalo and Madrigal de las Altas Torres. A separate tradition of Mudéjar style became highly developed in Aragon, with three main focuses at Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Province of Zaragoza, Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Ara ...

, Calatayud

Calatayud (; 2014 pop. 20,658) is a municipality in the Province of Zaragoza, within Aragón, Spain, lying on the river Jalón, in the midst of the Sistema Ibérico mountain range. It is the second-largest town in the province after the capital, ...

, and Teruel

Teruel () is a city in Aragon, located in eastern Spain, and is also the capital of Teruel Province. It has a population of 35,675 in 2014 making it the least populated provincial capital in the country. It is noted for its harsh climate, with ...

, during the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries. In Teruel a wide group of imposing churches and towers were built. Other fine examples of Mudéjar can be found in Casa de Pilatos in Seville, Santa Clara Monastery in Tordesillas, or the churches of Toledo, one of the oldest and most outstanding Mudéjar centers. In Toledo, the synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of wor ...

s of Santa María la Blanca and El Tránsito

El Tránsito is a municipality in the department of San Miguel, El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordere ...

(both Mudéjar though not Christian) deserve special mention.

Renaissance

In Spain, Renaissance styles began to be grafted onto Gothic forms in the last decades of the 15th century. The forms that started to spread were made mainly by local architects: that is the cause of the creation of a specifically

In Spain, Renaissance styles began to be grafted onto Gothic forms in the last decades of the 15th century. The forms that started to spread were made mainly by local architects: that is the cause of the creation of a specifically Spanish Renaissance

The Spanish Renaissance was a movement in Spain, emerging from the Italian Renaissance in Italy during the 14th century, that spread to Spain during the 15th and 16th centuries.

This new focus in art, literature,

quotes and science inspired ...

that brought the influence of southern Italian architecture, sometimes from illuminated books and paintings, mixed with the gothic tradition and local idiosyncrasies. The new style was called Plateresque

Plateresque, meaning "in the manner of a silversmith" (''plata'' being silver in Spanish), was an artistic movement, especially architectural, developed in Spain and its territories, which appeared between the late Gothic and early Renaissance ...

because of the extremely decorated façades that brought to the mind the decorative motifs of the intricately detailed work of silversmith

A silversmith is a metalworker who crafts objects from silver. The terms ''silversmith'' and ''goldsmith'' are not exactly synonyms as the techniques, training, history, and guilds are or were largely the same but the end product may vary grea ...

s, the "plateros". Classical orders and candelabra motifs (''a candelieri'') were combined freely into symmetrical wholes.

In that scenery, the Palace of Charles V by Pedro Machuca

Pedro Machuca (c. 1490 in Toledo, Spain – 1550 in Granada) is mainly remembered as the Spanish architect responsible for the design of the Palace of Charles V (begun 1528) adjacent to the Alcazar in Granada. The significance of this work is th ...

in Granada was an unexpected achievement in the most advanced Renaissance of the moment. The palace can be defined as an anticipation of the Mannerism

Mannerism, which may also be known as Late Renaissance, is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Ital ...

, due to its command of classical language and its breakthrough aesthetic achievements. It was constructed before the main works of Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was ins ...

and Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be one of t ...

. Its influence was very limited and poorly understood, the Plateresque forms prevailed in the general panorama.

As decades passed, the Gothic influence disappeared and the research of an orthodox classicism reached high levels. Although Plateresque is a commonly used term to define most of the architectural production of the late 15th and first half of 16th century, some architects acquired a more sober personal style, like Diego Siloe and

As decades passed, the Gothic influence disappeared and the research of an orthodox classicism reached high levels. Although Plateresque is a commonly used term to define most of the architectural production of the late 15th and first half of 16th century, some architects acquired a more sober personal style, like Diego Siloe and Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón

Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón (1500–1577) was a Spanish architect of the Renaissance.

He was born at Rascafría. His work alternated the late gothic with the renaissance style. His workings include the Palace of Monterrey in Salamanca, the Pal ...

. Examples include the façades of the University of Salamanca

The University of Salamanca ( es, Universidad de Salamanca) is a Spanish higher education institution, located in the city of Salamanca, in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It was founded in 1218 by King Alfonso IX. It is t ...

and of the Convent of San Marcos in León.

The highlight of Spanish Renaissance is represented by the Royal Monastery of El Escorial

El Escorial, or the Royal Site of San Lorenzo de El Escorial ( es, Monasterio y Sitio de El Escorial en Madrid), or Monasterio del Escorial (), is a historical residence of the King of Spain located in the town of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, u ...

, built by Juan Bautista de Toledo

Juan Bautista de Toledo (c. 1515 – 19 May 1567) was a Spanish architect. He was educated in Italy, in the Italian High Renaissance. As many Italian renaissance architects, he had experience in both architecture and military and civil public wo ...

and Juan de Herrera

Juan de Herrera (1530 – 15 January 1597) was a Spanish architect, mathematician and geometrician.

One of the most outstanding Spanish architects in the 16th century, Herrera represents the peak of the Renaissance in Spain. His sober style rea ...

, where a much closer adherence to the art of ancient Rome was overpassed by an extremely sober style. The influence from Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

roofs, the symbolism of the scarce decoration and the precise cut of the granite established the basis for a new style, the Herrerian. A disciple of Herrera, Juan Bautista Villalpando was influential for interpreting the recently revived text of Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

to suggest the origin of the classical orders in Solomon's Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (, , ), was the Temple in Jerusalem between the 10th century BC and . According to the Hebrew Bible, it was commissioned by Solomon in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited by t ...

.

Baroque