Socii on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''socii'' ( in English) or '' foederati'' ( in English) were confederates of

The ''socii'' ( in English) or '' foederati'' ( in English) were confederates of

The ''socii'' ( in English) or '' foederati'' ( in English) were confederates of

The ''socii'' ( in English) or '' foederati'' ( in English) were confederates of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and formed one of the three legal denominations in Roman Italy (''Italia'') along with the Roman citizens (''Cives'') and the '' Latini''. The ''Latini'', who were simultaneously special confederates (''Socii Latini'') and semi-citizens (''Cives Latini''), should not be equated with the homonymous Italic people of which Rome was part (the Latins). This tripartite organisation lasted from the Roman expansion in Italy (509-264 BC) to the Social War (91–87 BC)

The Social War (from Latin , properly 'war of the allies'), also called the Italian War or the Marsic War, was fought from 91 to 87 BC between the Roman Republic and several of its autonomous allies () in Italy. The Italian allies wanted ...

, when all peninsular inhabitants were awarded Roman citizenship.

Treaties known as ''foedus'' served as the basic template for Rome's settlement with the large array of tribes and city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s of the whole Italian peninsula. The confederacy had its origin in the ''foedus Cassianum

According to Roman tradition, the ''Foedus Cassianum'' ( in English) or the Treaty of Cassius was a treaty which formed an alliance between the Roman Republic and the Latin League in 493 BC after the Battle of Lake Regillus. It ended the war betw ...

'' ("Treaty of Cassius", 493 BC) signed by the fledgling Roman republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

with its neighbouring Latin city-states shortly after the overthrow of the Roman monarchy in 510 BC. This provided for mutual defence by the two parties on the basis of an equal contribution to the annual military levy, which was probably under Roman overall command. The terms of the treaty were probably more acceptable to the Latins than the previous type of Roman hegemony, that of the Tarquin kings, as the latter had probably required the payment of tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conq ...

and not a simple military obligation.

In the fourth century BC, the original Latins were mostly granted Roman citizenship. But the terms of the ''foedus'' was extended to about 150 other tribes and city-states. When a state was defeated, a part of its territory would be annexed by Rome to provide land for Roman/Latin colonists. The latter, although Roman citizens, were required to give up their citizen rights on joining a colony, and accept the status of ''socii''. This was in order that Latin colonies could act as "watchdogs" on the other ''socii'' in the allied military formations, the '' alae''. The defeated state would be allowed to keep the rest of its territory in return for binding itself to Rome with an unequal ''foedus'', one that would forge a state of perpetual military alliance with the Roman Republic. This would require the ally to "have the same friends and enemies as Rome", effectively prohibiting war against other ''socii'' and surrendering foreign policy to Rome. Beyond this, the central, and in most cases sole, obligation on the ally was to contribute to the confederate army, on demand, a number of fully equipped troops up to a specified maximum each year, to serve under Roman command.

The Roman confederation had fully evolved by 264 BC and remained for 200 years the basis of the Roman military structure. From 338 to 88 BC, Roman legions were invariably accompanied on campaign by roughly the same numbers of confederated troops organised into two units called ''alae'' (literally "wings", as confederated troops would always be posted on the flanks of the Roman battle-line, with the Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period o ...

s holding the centre). 75% of a normal consular army's cavalry was supplied by the Italian ''socii''. Although the ''socii'' provided around half the levies raised by Rome in any given year, they had no say in how those troops were used. Foreign policy and war were matters exclusively in the hands of the Roman consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

and the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

.

Despite the loss of independence and heavy military obligations, the system provided substantial benefits for the ''socii''. Most importantly, they were freed from the constant threat of aggression from their neighbours that had existed in the anarchic centuries prior to the imposition of the ''pax Romana

The Pax Romana (Latin for 'Roman peace') is a roughly 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is identified as a period and as a golden age of increased as well as sustained Roman imperialism, relative peace and order, prosperous stabilit ...

''. In addition, the Roman alliance protected the Italian peninsula from external invasion, such as the periodic and devastating incursions of Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They sp ...

from the Po Valley. Although no longer in control of war and foreign policy, each ''socius'' remained otherwise fully autonomous, with its own laws, system of government, coin

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order ...

age and language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

. Moreover, the military burden was only half that shouldered by Roman citizens, as the latter numbered only about half the population of the ''socii'', but provided around half the total levies. Despite this, allied troops were allowed to share war booty on a 50–50 basis with Romans.

The relationship between Rome and the Latin cities remained ambivalent, and many ''socii'' rebelled against the alliance whenever the opportunity arose. The best opportunities were provided by the invasion of Italy by the Greek king Pyrrhus from 281 to 275 BC, and by the invasion of Italy by Carthaginian general Hannibal from 218 to 203 BC. During these invasions, many ''socii'' joined the invaders, mostly Oscan

Oscan is an extinct Indo-European language of southern Italy. The language is in the Osco-Umbrian or Sabellic branch of the Italic languages. Oscan is therefore a close relative of Umbrian.

Oscan was spoken by a number of tribes, including t ...

-speakers of southern Italy, most prominently the Samnite tribes, who were Rome's most implacable enemy. At the same time, however, many ''socii'' remained loyal, motivated primarily by antagonisms with neighbouring rebels. Even after Rome's disaster at the Battle of Cannae (216 BC), over half the ''socii'' (by population) did not defect and Rome's military alliance was ultimately victorious.

In the century following the Second Punic War, Italy was rarely threatened by external invasion (save by the occasional Gallic or Germanic horde) and Rome and her allies embarked on aggressive expansion overseas, in Spain, Africa and the Balkans. Despite the fact that the alliance was no longer acting defensively, there was virtually no protest from the ''socii'', most likely because the latter benefited equally in the enormous amounts of war booty yielded by these campaigns.

But, beneath the surface, resentment was building among the ''socii'' about their second-class status as ''peregrini

In the early Roman Empire, from 30 BC to AD 212, a ''peregrinus'' (Latin: ) was a free provincial subject of the Empire who was not a Roman citizen. ''Peregrini'' constituted the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants in the 1st and 2nd centur ...

'' i.e. non-citizens (except for the Latin colonists, who could regain their citizenship by moving to Roman territory). The Roman military confederation now became a victim of its own success in forging a united nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by th ...

out of the patchwork of ethnicities and states. The ''socii'' rebelled ''en masse'', including many that had remained steadfast in the past, launching the Social War. But, unlike on previous occasions, their aim was to join the Roman state as equal citizens, not to secede from it. Although the ''socii'' were defeated on the battlefield, they gained their main demand. By the end of the war in 87 BC, all inhabitants of peninsular Italy had been granted the right to apply for Roman citizenship.

Meanings of the term "Latin"

The Romans themselves used the term "Latin" loosely, and this can be confusing. The term was used to describe what were actually three distinct groups: # The Latin tribe strictly speaking, to which the Romans themselves belonged. These were the inhabitants of Latium Vetus ("OldLatium

Latium ( , ; ) is the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded and grew to be the capital city of the Roman Empire.

Definition

Latium was originally a small triangle of fertile, volcanic soil ( Old Latium) on w ...

"), a small region south of the river Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by th ...

, whose inhabitants were speakers of the Latin language

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of ...

.

# The inhabitants of Latin colonies. These were ''coloniae'' made up of mixed Roman/Latin colonists.

# All the Italian allies of Rome, not only the Latin colonies, but also the other non-Latin allies (''socii'').

In this article, to avoid confusion, only group (1) will be referred to as "Latins". Group (2) will be called "Latin colonies or colonists" and group (3) will be referred to as "Italian confederates". ''Socii'' will refer to groups (2) and (3) combined.

Ethnic composition of ancient Italy

The Italian peninsula at this time was a patchwork of different ethnic groups, languages and cultures. These may be divided into the following broad nations: # The Italic tribes, that dominated central and southern Italy, as well as northeastern Italy. These included the original Latins and a large number of other tribes, most notably the Samnites (actually a league of tribes) who dominated south central Italy. In addition to Latin, these tribes spokeUmbrian

Umbrian is an extinct Italic language formerly spoken by the Umbri in the ancient Italian region of Umbria. Within the Italic languages it is closely related to the Oscan group and is therefore associated with it in the group of Osco-Umbrian ...

and Oscan

Oscan is an extinct Indo-European language of southern Italy. The language is in the Osco-Umbrian or Sabellic branch of the Italic languages. Oscan is therefore a close relative of Umbrian.

Oscan was spoken by a number of tribes, including t ...

dialects, all closely related Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, D ...

. The Italic tribes were mostly tough hill-dwelling pastoralists, who made superb infantrymen, especially the Samnites. It is believed that the latter invented the manipular infantry formation and the use of javelins and oblong shields, which were adopted by the Romans at the end of the Samnite Wars

The First, Second, and Third Samnite Wars (343–341 BC, 326–304 BC, and 298–290 BC) were fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites, who lived on a stretch of the Apennine Mountains south of Rome and north of the Lucanian tribe ...

. An isolated Italic group were the Veneti in the northeast. They gave their name to the region they inhabited, Venetia, a name chosen centuries afterwards for the new founded capital of the allied people of the Venetian Lagoon, who would become the Most Serene Republic of Venice.

# The Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

, who had colonised the coastal areas of southern Italy from c. 700 BC onwards, which was known to the Romans as ''Magna Graecia'' ("Greater Greece") for that reason. The Greek colonies had the most advanced civilisation in the Italian peninsula, much of which was adopted by the Romans. Their language, although Indo-European, was quite different from Latin. As maritime cities, the Greeks' primary military significance was naval. They invented the best warship of the ancient world, the trireme. Some of the original Greek colonies (such as Capua and Cumae) had been subjugated by the neighbouring Italic tribes and become Oscan-speaking in the period up to 264 BC. The surviving Greek cities in 264 were all coastal: Neapolis, Poseidonia ( Paestum), Velia, Rhegium

Reggio di Calabria ( scn, label= Southern Calabrian, Riggiu; el, label=Calabrian Greek, Ρήγι, Rìji), usually referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria. It has an estimated popul ...

, Locri, Croton, Thurii

Thurii (; grc-gre, Θούριοι, Thoúrioi), called also by some Latin writers Thurium (compare grc-gre, Θούριον in Ptolemy), for a time also Copia and Copiae, was a city of Magna Graecia, situated on the Tarentine gulf, within a s ...

, Heraclea, Metapontum and Tarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Camp ...

. The most populous were Neapolis, Rhegium and Tarentum, all of which had large, strategic harbours on the Tyrrhenian, the Strait of Messina and the Ionian sea respectively. Tarentum had, until c. 300 BC, been a major power and ''hegemon'' (leading power) of the Italiote league

The Italiotes ( grc-gre, Ἰταλιῶται, ') were the pre-Roman Greek-speaking inhabitants of the Italian Peninsula, between Naples and Sicily.

Greek colonization of the coastal areas of southern Italy and Sicily started in the 8th cen ...

, a confederation of the Greek cities in Italy. But its military capability was crippled by the Romans, who defeated Tarentum by 272 BC.

# The Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

, who dominated the region between the rivers Arno

The Arno is a river in the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the most important river of central Italy after the Tiber.

Source and route

The river originates on Monte Falterona in the Casentino area of the Apennines, and initially takes a ...

and Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by th ...

, still retaining a derived name (Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

) today. The Etruscans spoke a non Indo-European language which today is largely unknown and a distinctive culture. Some scholars believe Rome may have been an Etruscan city at the time of the Roman kings

The king of Rome ( la, rex Romae) was the ruler of the Roman Kingdom. According to legend, the first king of Rome was Romulus, who founded the city in 753 BC upon the Palatine Hill. Seven legendary kings are said to have ruled Rome until 509 BC ...

(conventionally 753–509 BC). The Etruscans had originally dominated the Po Valley, but had been progressively displaced from this region by the Gauls in the 4th century BC, separating them the Etruscan-speaking Raetians

The Raeti (spelling variants: ''Rhaeti'', ''Rheti'' or ''Rhaetii'') were a confederation of Alpine tribes, whose language and culture was related to those of the Etruscans. Before the Roman conquest, they inhabited present-day Tyrol in Austria, ...

in the Alpine region. City-states with territories.

# The Campanians, occupying the fertile plain between the river Volturno

The Volturno (ancient Latin name Volturnus, from ''volvere'', to roll) is a river in south-central Italy.

Geography

It rises in the Abruzzese central Apennines of Samnium near Castel San Vincenzo (province of Isernia, Molise) and flows sout ...

and the bay of Naples. These were not a distinct ethnic group, but a mixed Samnite/Opici The Opici were an ancient italic people of the Latino-Faliscan group who lived in the region of Campania. They settled in the area in the late Bronze Age but their territory was later conquered during the Iron Age by the Osci, another Italic people ...

an population with Etruscan elements. The Samnites had conquered the Greek and Etruscan city-states in the period 450–400 BC. Speaking the Oscan language, they developed a distinctive culture and identity. Although partly of Samnite blood, they came to regard the mountain Samnites that surrounded them as a major threat, leading them to ask for Roman protection from 340 BC onwards. City-states with territories. As plains-dwellers, horses played an important role for the Campanians and their cavalry was considered the best in the peninsula. Their main city was Capua, probably the second-largest city in Italy at this time. Other important cities were Nola

Nola is a town and a municipality in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, southern Italy. It lies on the plain between Mount Vesuvius and the Apennines. It is traditionally credited as the diocese that introduced bells to Christian wo ...

, Acerrae, Suessula

Suessula (Greek: ) was an ancient city of Campania, southern Italy, situated in the interior of the peninsula, near the frontier with Samnium, between Capua and Nola, and about 7 km northeast of Acerrae, Suessula is now a vanished city an ...

# The Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They sp ...

, who had migrated into, and colonised, the plain of the Po river (''pianura padana'') from c. 390 BC onwards. This region is now part of northern Italy, but until the rule of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

was not regarded as part of Italy at all, but part of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

. The Romans called it Cisalpine Gaul ("Gaul this side of the Alps"). They spoke Gaulish

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switze ...

dialects, part of the Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foo ...

group of Indo-European languages. Tribal-based territories with some city-like centres.

# The Ligurians

The Ligures (singular Ligur; Italian: liguri; English: Ligurians) were an ancient people after whom Liguria, a region of present-day north-western Italy, is named.

Ancient Liguria corresponded more or less to the current Italian reg ...

, occupying the region known to the Romans (and still called today) as Liguria

Liguria (; lij, Ligûria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

, southwest of the Gauls. It is unclear whether their language was non Indo-European (related to Iberian), Italic, or Celtic (related to Gaulish). Most likely, they spoke a Celto-Italic hybrid language.

# The Messapii, who occupied the southern part of the Apulian peninsula, in SE Italy. Believed from inscriptions to be speakers of a tongue related to Illyrian (an Indo-European language), these were in perpetual conflict over territory with the Greeks of Tarentum.

Background: early Rome (to 338 BC)

Ancient historians' accounts of the history of Rome before it was destroyed by the Gauls in 390 BC are regarded as highly unreliable by modern historians. Livy, the main surviving ancient source on the early period, himself admits that the earlier period is very obscure and that his own account is based on legend rather than written documentation, as the few written documents that did exist in the earlier period were mostly lost in the Gallic sack. There is a tendency among ancient authors to create anachronisms. For example, Rome's so-called " Servian Wall" was attributed to the legendary king Servius Tullius in c. 550 BC, but archaeology and a note in Livy himself show that the wall was built after the sack of Rome by the Gauls. Servius Tullius was also credited with the centuriate organisation of the Roman citizen body which again scholars agree cannot have been established by Servius in the form described by Livy in book I.43. His ''centuriae'' were supposedly designed to organise the military levy, but would have resulted in the majority of the total levy being raised from the two top property classes, which were also the smallest numerically, a result that is clearly nonsensical. Instead, the reform must date from much later, certainly after 400 BC and probably after 300. (Indeed, it has even been suggested that the centuriate organisation was not introduced before the Second Punic War and the currency reform of 211 BC. The sextantal '' as'', the denomination used by Livy to define the centuriate property thresholds, did not exist until then. But this argument is regarded as weak by some historians, as Livy may simply have converted older values). Despite this, the broad trends of early Roman history as related by the ancient authors are reasonably accurate. According to Roman legend, Rome was founded by Romulus in 753 BC. However, the vast amount of archaeological evidence uncovered since the 1970s suggests that Rome did not assume the characteristics of a united city-state (as opposed to a group of separate hilltop settlements) before around 625. The same evidence, however, has also conclusively discredited A. Alfoldi's once-fashionable theory that Rome was an insignificant settlement until c. 500 (and that, consequently, the Republic was not established before c. 450). There is now no doubt that Rome was a major city in the period from 625 to 500 BC, when it had an area of c. 285 hectares and an estimated population of 35,000. This made it the second-largest in Italy (after Tarentum) and about half the size of contemporaryAthens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

(585 hectares, inc. Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saro ...

). Also, few scholars today dispute that Rome was ruled by kings in its archaic period, although whether any of the seven names of kings preserved by tradition are historical remains uncertain (Romulus himself is generally regarded as mythical). It is also likely that there were several more kings than those preserved by tradition, given the long duration of the regal era (even if it did start in 625 rather than 753).

The Roman monarchy, although an autocracy, did not resemble a medieval monarchy. It was not hereditary and based on "divine right", but elective and subject to the ultimate sovereignty of the people. The king (''rex'', from root-verb ''regere'', literally means simply "ruler") was elected for life by the people's assembly (the ''comitia curiata'' originally), although there is strong evidence that the process was in practice controlled by the patricians, a hereditary aristocratic caste. Most kings were non-Romans brought in from abroad, doubtless as a neutral figure who could be seen as above patrician factions. Although blood relations could succeed, they were still required to submit to election. The position and powers of a Roman king were thus similar to those of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

when he was appointed dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in time ...

in perpetuity in 44 BC, and indeed of the Roman emperors.

According to Roman tradition, in 616 BC, an Etruscan named Lucumo from the town of Tarquinii, was elected king of Rome as Lucius Tarquinius Priscus. He was succeeded by his son-in-law, Servius Tullius, and then by his son, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. The establishment of this Etruscan "dynasty" has led some dated historians to claim that late regal Rome was occupied by troops from Tarquinii militarily and culturally Etruscanised. But this theory has been dismissed as a myth by Cornell and other more modern historians, who point to the extensive evidence that Rome remained politically independent, as well as linguistically and culturally a Latin city. In relation to the army, the Cornell faction argue that the introduction of heavy infantry in the late regal era followed Greek, not Etruscan, models.

In addition, it seems certain that the kings were overthrown c. 500 BC, probably as a result of a much more complex and bloody revolution than the simple drama of the rape of Lucretia related by Livy, and that they were replaced by some form of collegiate rule. It is likely that the revolution that overthrew the Roman monarchy was engineered by the patrician caste and that its aim was not, as rationalised later by ancient authors, the establishment of a democracy, but of a patrician-dominated oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate ...

. The proverbial "arrogance" and "tyranny" of the Tarquins, epitomised by the Lucretia incident, is probably a reflection of the patricians' fear of the Tarquins' growing power and their erosion of patrician privilege, most likely by drawing support from the plebeians

In ancient Rome, the plebeians (also called plebs) were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words " commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Etymology

The precise origins ...

(commoners). To ensure patrician supremacy, the autocratic power of the kings had to be fragmented and permanently curtailed. Thus, the replacement of a single ruler by a collegiate administration, which soon evolved into two Praetors, later called Consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

, with equal powers and limited terms of office (one year, instead of the life tenancy of the kings). In addition, power was further fragmented by the establishment of further collegiate offices, known to history as Roman magistrates

The Roman magistrates were elected officials in Ancient Rome.

During the period of the Roman Kingdom, the King of Rome was the principal executive magistrate.Abbott, 8 His power, in practice, was absolute. He was the chief priest, lawgiver, ...

: (three Aediles and four Quaestors). Patrician supremacy was assured by limiting eligibility to hold the republican offices to patricians only.

The establishment of a hereditary oligarchy obviously excluded wealthy non-patricians from political power and it is this class that led plebeian opposition to the early Republican settlement. The early Republic (510–338 BC) saw a long and often bitter struggle for political equality, known as the Conflict of the Orders

The Conflict of the Orders, sometimes referred to as the Struggle of the Orders, was a political struggle between the plebeians (commoners) and patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic lasting from 500 BC to 287 BC in which the pl ...

, against the patrician monopoly of power. The plebeian leadership had the advantage that they represented the vast majority of the population, therfor also the majority of the Roman levy and of their own growing wealth. Milestones in their ultimately successful struggle are the establishment of a plebeian assembly (the ''concilium plebis'') with some legislative power and to elect officers called tribunes of the plebs, who had the power to veto Senatorial decrees (494); and the opening of the Consulship to plebeians (367). By 338, the privileges of the patricians had become largely ceremonial (such as the exclusive right to hold certain state priesthoods). But this does not imply a more democratic form of government. The wealthy plebeians who had led the "plebeian revolution" had no more intention of sharing real power with their poorer and far more numerous fellow-plebeians than did the patricians. It was probably at this time (around 300 BC) that the population was divided, for the purposes of taxation and military service, into seven classes based on an assessment of their property. The two top classes, numerically the smallest, accorded themselves an absolute majority of the votes in the main electoral and legislative assembly. Oligarchy based on birth had been replaced by oligarchy based on wealth.

Political organisation of the Roman Republic

By c. 300 BC, theRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

had attained its evolved structure, which remained essentially unchanged for three centuries. In theory, Rome's republican constitution was democratic, based on the principle of the sovereignty of the Roman people. It had also developed an elaborate set of checks and balances to prevent the excessive concentration of power. The two Consuls, together with other republican Magistrates, were elected annually by the Roman citizenry (male citizens over 14 years old only) voting by '' centuria'' (voting constituency) at the ''comitia centuriata

The Centuriate Assembly ( Latin: ''comitia centuriata'') of the Roman Republic was one of the three voting assemblies in the Roman constitution. It was named the Centuriate Assembly as it originally divided Roman citizens into groups of one hundr ...

'' (electoral assembly), held each year on the Field of Mars The term Field of Mars ( la, Campus Martius) goes back to antiquity, and designates an area, inside or near a city, used as a parade or exercise ground by the military.

Notable examples of places which were used for these purposes include:

* Campus ...

in Rome. The popular assemblies also had the right to promulgate laws (''leges''). The Consuls, who combined both civil and military functions, had equal authority and the right to veto each other's decisions. The main policy-making institution, the Senate, was an unelected body composed mostly of Roman aristocrats but its decrees could not contravene ''leges'', and motions in the Senate could be vetoed by any one of 10 tribunes of the plebs, elected by the ''concilium plebis'', an assembly restricted to plebeian members only. The tribunes could also veto decisions made by the Consuls.

But these constitutional arrangements were far less democratic than they might appear, as elections were rigged heavily in favour of the wealthiest echelon of society. The centuriate organisation of the Roman citizen-body may be summarised as follows:

N.B. An extra four ''centuriae'' were allocated to engineers, trumpeters et al., to make a total of 193 ''centuriae''. There is a discrepancy in the minimum rating for legionary service between Polybius (400 ''drachmae'') and Livy (1,100). In addition, Polybius states that the ''proletarii'' were assigned to naval service while Livy simply states that they were exempt from military service. In both cases, Polybius is to be preferred, as 1,100 ''drachmae'' seems too high a figure for destitute individuals and it is likely that the Roman military would have made use of the manpower of this group.

The table shows that the richest two property classes combined, the '' equites'' (knights, including the six centuriae probably reserved for patricians), together with the first property class, were allocated an absolute majority of the votes (98 of 193 ''centuriae''), despite being a small minority of the population. Their precise proportion is unknown, but was most likely under 5% of the citizen-body. These classes supplied a legion's cavalry, just 6.6% of the unit's total effectives (300 of 4,500), which is probably greater than their proportionate share, as the lowest class was excluded from legionary service. Overall, votes were allocated in inverse proportion to population. Thus the lowest social echelon (the ''proletarii'', under 400 ''drachmae''), was allocated just 1 of the 193 ''centuriae'', despite being probably the largest. As Livy himself puts it: "Thus every citizen was given the illusion of wielding power through the right to vote, but in reality the aristocracy remained in full control. For the ''centuriae'' of knights were summoned first to vote, and then the ''centuriae'' of the First Property Class. In the rare event of a majority not being attained, the Second Class was called, but it was hardly ever necessary to consult the lowest classes." Also in its legislative capacity, the popular assembly offered little scope for democratic action. For this purpose, the ''comitia'' could only meet when summoned by a Magistrate. Participants could only vote (by ''centuria'') for or against propositions ('' rogationes'') put before them by the convening Magistrate. No amendments or motions from the floor were admissible. In modern terms, the legislative activity of the ''comitia'' amounted to no more than a series of referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

s, and in no sense resembled the role of a parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

.

Further, the period of the Samnite wars saw the emergence of the Senate as the predominant political organ at Rome. In the early Republic, the Senate had been an ''ad hoc'' advisory council whose members served at the pleasure of the Consuls. While no doubt influential as a group of friends and confidants of the Consuls, as well as experienced ex-Magistrates, the Senate had no formal or independent existence. Power rested with the Consuls, acting with the ratification of the ''comitia'', a system described as "plebiscitary" by Cornell. This situation changed with the ''Lex Ovinia

The Plebiscitum Ovinium (often called the ''Lex Ovinia'') was an initiative by the Plebeian Council that transferred the power to revise the list of members of the Roman Senate (the ''lectio senatus'') from consuls to censors.

Date

Since Appius C ...

'' (promulgated sometime in the period from 339 to 318 BC), which transferred authority to appoint (and remove) members of the Senate from the Consuls to the Censors, two new Magistrates elected at 5-yearly intervals, whose specific job was to hold a census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses inc ...

of Roman citizens and their property. The ''Lex Ovinia'' set specific criteria for such appointments or removals (although these are not precisely known). The result was that the Senate now became a formal constitutional entity. Its members now held office for life (or until expelled by the Censors), and were thus freed from control by the Consuls.

In the period following the ''Lex Ovinia'', the Consuls were gradually reduced to executive servants of the Senate. The concentration of power in the hands of the Senate is exemplified by its assumption of the power of '' prorogatio'', the extension of the ''imperium'' (mandate) of Consuls and other Magistrates beyond its single year. It appears that ''prorogatio'' could previously be granted only by the ''comitia'' e.g. in 326 BC. By the end of the Samnite Wars in 290, the Senate enjoyed complete control over virtually all aspects of political life: finance, war, diplomacy, public order and the state religion. The rise of the Senate's role was the inevitable consequence of the increasing complexity of the Roman state due to its expansion, which made government by short-term officers such as the Consuls and by plebiscite impractical.

The Senate's monopoly of power in turn entrenched the political supremacy of the wealthiest echelon. The 300 members of the Senate were mostly a narrow, self-perpetuating ''clique'' of ex-Consuls (''consulares'') and other ex-Magistrates, virtually all members of the wealthy classes. Within this elite, charismatic personalities, who might challenge senatorial supremacy by allying with the commoners, were neutralised by various devices, such as the virtual abolition of "iteration", the re-election of consuls for several successive terms, a practice common before 300 BC. (In the period from 366 to 291, eight individuals held the consulship four or more times, while from 289 to 255, none did, and few were even elected twice. Iteration was temporarily resorted to again during the emergency conditions of the Second Punic War). The Roman polity exhibited, in the words of T. J. Cornell, an historian of early Rome, "the classic symptoms of oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate ...

, a system of government that depends on rotation of office within a competitive elite, and the suppression of charismatic individuals by peer-group pressure, usually exercised by a council of elders."

External relations of early Rome

Because of the poverty of the sources, only the bare outline of Rome's external relations in the early period can be reliably discerned. It appears likely that Rome in the period 550–500, conventionally known as the period it was ruled by the Tarquin dynasty, established its hegemony over its Latin neighbours. The fall of the Roman monarchy was followed by a war with the Latins, who probably took advantage of the political turmoil in Rome to attempt to regain their independence. This war was brought to an end in 493 BC by the conclusion of a treaty called ''Foedus Cassianum

According to Roman tradition, the ''Foedus Cassianum'' ( in English) or the Treaty of Cassius was a treaty which formed an alliance between the Roman Republic and the Latin League in 493 BC after the Battle of Lake Regillus. It ended the war betw ...

'', which lay the foundations for the Roman military alliance. According to the sources, this was a bilateral treaty between the Romans and the Latins. It provided for a perpetual peace between the two parties; a defensive alliance by which the parties pledged mutual assistance in case of attack; a promise not to aid or allow passage to each other's enemies; the equal division of spoils of war (half to Rome, half to the other Latins) and provisions to regulate trade between the parties. In addition, the treaty may have provided for the Latin armed forces levied under the treaty to be led by a Roman commander. These terms served as the basic template for Rome's treaties with all the other Italian ''socii'' acquired over the succeeding two centuries.

As we do not know the nature of the Tarquinian hegemony over the Latins, we cannot tell how the terms of the Cassian treaty differed from those imposed by the Tarquins. But it is likely that Tarquin rule was more onerous, involving the payment of tribute, while the Republican terms simply involved a military alliance. The impetus to form such an alliance was probably provided by the acute insecurity caused by a phase of migration and invasion of the lowland areas by Italic mountain tribes in the period after 500 BC. The Sabines, Aequi and Volsci neighbours of Latium assailed the Latins, the Samnites invaded and subjugated the Greco-Etruscan cities of Campania, while the Messapii, Lucani and Bruttii in the South attacked the Greek coastal cities, crippling Tarentum and reducing the independent Greek cities on the Tyrrhenian coast to just Neapolis and Velia.

The new Romano-Latin military alliance proved strong enough to repel the incursions of the Italic mountain tribes, but it was a very tough struggle. Intermittent wars, with mixed fortunes, continued until c. 395 BC. The Sabines disappear from the record in 449 (presumably subjugated by the Romans), while campaigns against the Aequi and Volsci seem to have reached a turning point with the major Roman victory on Mount Algidus in 431. In the same period, the Romans fought three wars against their nearest neighbouring Etruscan city-state, Veii

Veii (also Veius; it, Veio) was an important ancient Etruscan civilization, Etruscan city situated on the southern limits of Etruria and north-northwest of Rome, Italy. It now lies in Isola Farnese, in the Comuni of the Province of Rome, comune ...

, finally reducing the city in 396. Although the annexation of Veii's territory probably increased the ''ager Romanus'' by c. 65%, this seems a modest gain for a century of warfare.

At this juncture, Rome was crushed by an invasion of central Italy by the Senones Gallic tribe. Routed at the river Allia in 390 BC, the Roman army fled to Veii, leaving their city at the mercy of the Gauls, who proceeded to ransack it and then demand a huge ransom in gold to leave. The effects of this disaster on Roman power are a matter of controversy between scholars. The ancient authors emphasize the catastrophic nature of the damage, claiming that it took a long time for Rome to recover. Cornell, however, argues that the ancients greatly exaggerated the effects and cites the lack of archaeological evidence for major destruction, the early resumption of an aggressive expansionist policy and the building of the "Servian" Wall as evidence that Rome recovered swiftly. The Wall, whose 11 km-circuit enclosed 427 hectares (an increase of 50% over the Tarquinian city) was a massive project which would have required an estimated five million man-hours to complete, implying plentiful financial and labour resources. Against this, Eckstein argues that the history of Rome in the 50 years subsequent to 390 appears a virtual replay of the previous century. There were wars against the same enemies except Veii (i.e. the Volsci, Aequi and Etruscans) in the same geographical area, and indeed against other Latin city-states, such as Praeneste and Tibur

Tivoli ( , ; la, Tibur) is a town and in Lazio, central Italy, north-east of Rome, at the falls of the Aniene river where it issues from the Sabine hills. The city offers a wide view over the Roman Campagna.

History

Gaius Julius Solin ...

, just 30 miles away. In addition, a treaty concluded with Carthage c. 348 seems to describe Rome's sphere of control as much the same area as in a previous treaty signed in the first years of the Republic 150 years earlier: just the Latium Vetus, and not even all of that.

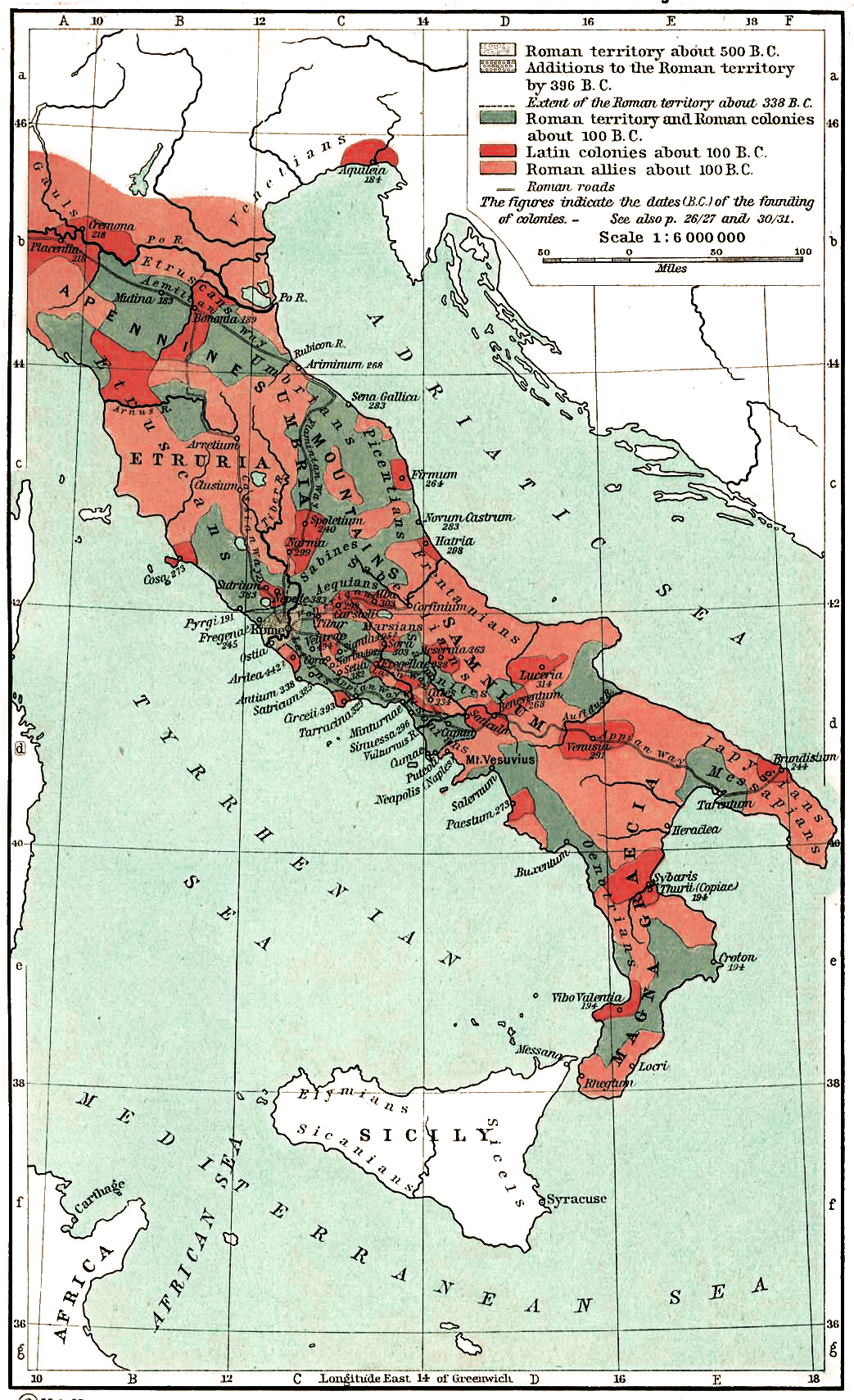

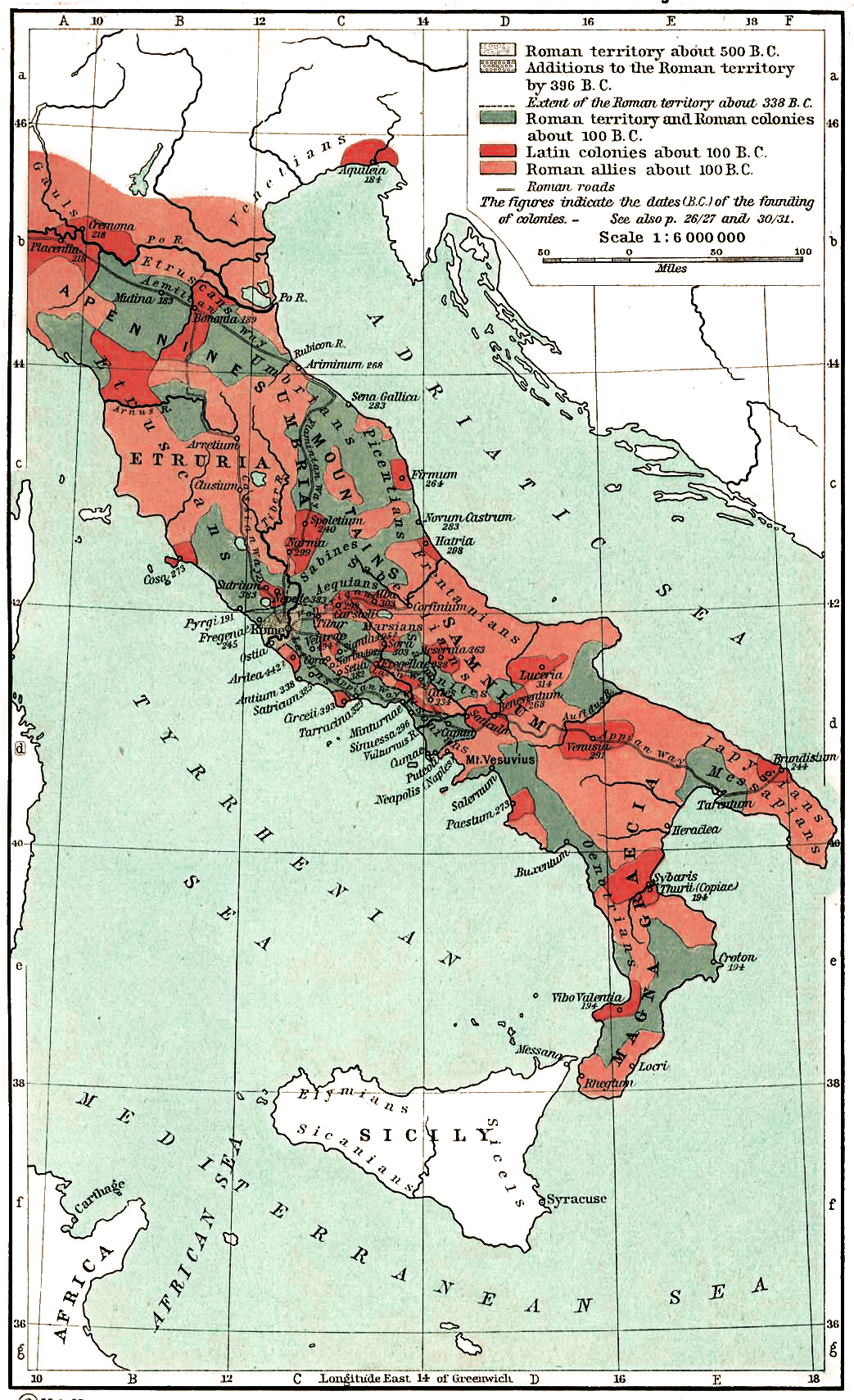

Roman conquest of Italy 338–264 BC

The 75-year period between 338 BC and the outbreak of the First Punic War in 264 saw an explosion of Roman expansion and the subjugation of the entire peninsula to Roman political hegemony, achieved by virtually incessant warfare. Roman territory (''ager Romanus'') grew enormously in size, from c. 5,500 to 27,000 km2, c. 20% of peninsular Italy. The Roman citizen population nearly tripled, from c. 350,000 to c. 900,000, c. 30% of the peninsular population.Cornell (1995) 380 Latin colonies probably comprised a further 10% of the peninsula (about 12,500 km2). The remaining 60% of the peninsula remained in the hands of other Italian ''socii'' who were, however, forced to accept Roman supremacy. The expansion phase started with the defeat of the Latin League (338 BC) and the annexation of most of Latium Vetus. Subsequently, the main thrusts of expansion were southwards towards theVolturno

The Volturno (ancient Latin name Volturnus, from ''volvere'', to roll) is a river in south-central Italy.

Geography

It rises in the Abruzzese central Apennines of Samnium near Castel San Vincenzo (province of Isernia, Molise) and flows sout ...

river, annexing the territories of the Aurunci

The Aurunci were an Italic tribe that lived in southern Italy from around the 1st millennium BC. They were eventually defeated by Rome and subsumed into the Roman Republic during the second half of the 4th century BC.

Identity

Aurunci is the n ...

, Volsci, Sidicini and the Campanians themselves; and eastwards across the centre of the peninsula towards the Adriatic coast, incorporating the Hernici, Sabini, Aequi and Picentes. The years after the departure of Pyrrhus in 275 saw a further round of annexation, of substantial territories in southern Italy at the expense of the Lucani and Bruttii. The Bruttii lost large forest lands, whose timber was needed to build ships and the Lucani lost their most fertile land, the coastal plain on which the Latin colony of Paestum was established in 273. In the North, the Romans annexed the ''ager Gallicus'', a large stretch of plain on the Adriatic coast from the Senones Gallic tribe, with a Latin colony at Ariminum

Rimini ( , ; rgn, Rémin; la, Ariminum) is a city in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy and capital city of the Province of Rimini. It sprawls along the Adriatic Sea, on the coast between the rivers Marecchia (the ancient ''Ariminus ...

in 268. By 264, Rome controlled the entire Italian peninsula, either directly as Roman territory or indirectly through the ''socii''.

The prevailing explanation for this explosive expansion, as proposed in W. V. Harris' ''War and Imperialism in Republican Rome'' (1979), is that the Roman state was an exceptionally martial society, whose every class from the aristocracy downwards was militarised and whose economy was based on the spoils of annual warfare. Rome's neighbouring peoples, on the other hand, were seen as essentially passive victims who strove, ultimately unsuccessfully, to defend themselves against Roman aggression. More recently, however, Harris' theory of Roman "exceptionalism" has been challenged by A. M. Eckstein, who points out that Rome's neighbours were equally militaristic and aggressive and that Rome was just one competitor for territory and hegemony in a peninsula whose interstate relations were largely anarchic and lacking effective mechanisms for resolution of interstate disputes. It was a world of continuous struggle for survival, of ''terrores multi'' for the Romans, a phrase from Livy that Eckstein uses to describe the politico-military situation in the peninsula before the imposition of the ''pax Romana''. The reasons for the Romans' ultimate triumph was their superior manpower and political and military organisation.

Eckstein points out that it took 200 years of warfare for Rome to subdue just its Latin neighbours, as the Latin War did not end until 338 BC. This demonstrates that the other Latin cities were as martial as Rome itself. Before ''pax Romana'', the Etruscan city-states to the north existed, like the Latin states, in a state of "militarised anarchy", with chronic and fierce competition for territory and hegemony. The evidence is that every Etruscan city until 500 BC was sited on virtually impregnable hilltops and cliff edges. Despite these natural defences, they all acquired walls by 400. Etruscan culture was highly militaristic. Graves with weapons and armour were common and captured enemies were often offered as human sacrifice and their severed heads displayed in public, as happened to 300 Roman prisoners at Tarquinii in 358. It took the Romans a century and four wars (480–390) just to reduce Veii

Veii (also Veius; it, Veio) was an important ancient Etruscan civilization, Etruscan city situated on the southern limits of Etruria and north-northwest of Rome, Italy. It now lies in Isola Farnese, in the Comuni of the Province of Rome, comune ...

, a single neighbouring Etruscan city.

To the South, the Samnites had a reputation for martial ferocity unrivalled in the peninsula. Tough mountain-dwelling pastoralists, they are believed to have invented the manipular fighting unit adopted by the Romans. Like the Romans, their national symbol was a wolf, but a male wolf on the prowl, not a she-wolf suckling babies. All graves of male Samnites contain weapons. Livy several times describes the barbarity of their raids into Campania. Their military effectiveness was greatly enhanced by the formation of the Samnite League by the four Samnite tribal cantons (the Caudini, Hirpini, Caraceni and Pentri). This brought their forces under the unified command of a single general in times of crisis. It took the Romans three gruelling wars (the Samnite wars

The First, Second, and Third Samnite Wars (343–341 BC, 326–304 BC, and 298–290 BC) were fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites, who lived on a stretch of the Apennine Mountains south of Rome and north of the Lucanian tribe ...

, 343–290 BC), during which they suffered many severe reverses, to subjugate the Samnites. Even after this, the Samnites remained implacable enemies of Rome, seizing every opportunity to throw off the Roman yoke. They rebelled and joined both Pyrrhus and Hannibal when these invaded Italy (275 and 218 BC respectively). In the Social War (91–88 BC), the Samnites were the core of the rebel coalition, and Samnite generals led the Italian forces.

The southern Greek city of Taras (Tarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Camp ...

) had been founded by colonists from Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

. They retained some of their founders' martial culture. With the best natural harbour in Italy and a fertile hinterland, it was faced from the start with fierce competition from the other Greek colonies and resistance from the indigenous Messapii, an Illyrian-speaking people that occupied what the Romans called ''Calabria'' (the heel of Italy). By around 350 BC, the Tarentine statesman Archytas had established the city's hegemony over both sets of rivals. The city's army of 30,000 foot and 4,000 cavalry was then the largest in the peninsula. Tarentine cavalry was renowned for its quality and celebrated in the city's coins, which often showed youths on horseback placing wreaths over their mount's head. The Tarentines' most important cult was to Nike, the Greek goddess of Victory. A famous status of Nike which stood in the city centre was ultimately transferred to the Senate House in Rome by the emperor Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

.

Pattern of Roman expansion

The rise of Roman hegemony by three main means: (a) direct annexation of territory and incorporation of the existing inhabitants; (b) the foundation of Latin colonies on territory confiscated from defeated peoples; and (c) the binding of defeated peoples to Rome by treaties of perpetual alliance. (a) Since the inhabitants of Latium Vetus were the Romans' fellow-tribesmen, there was no reluctance to grant them full citizenship. But annexations outside Latium Vetus soon gathered pace. The Romans then encountered the problem that their new subjects could, if granted full Roman citizenship, outnumber original Latins in the citizen body, threatening Rome's ethnic and cultural integrity. The problem as solved by introducing ''civitas sine suffragio'' ("non-voting citizenship"), a second-class status which carried all the rights and obligations of full citizenship except the right to vote. By this device, the Roman republic could enlarge its territory without losing its character as a Latin city-state. The most important use of this device was the incorporation of the Campanian city-states into the ''ager Romanus'', bringing the most fertile agricultural land in the peninsula and a large population under Roman control. Also incorporated ''sine suffragio'' were several tribes on the fringes of Latium Vetus that had until that time been long-time enemies of Rome: the Aurunci, Volsci, Sabini and Aequi. (b) Alongside direct annexation, the second vehicle of Roman expansion was the ''colonia'' (colony), both Roman and Latin. Under Roman law, the lands of a surrendering enemy (''dediticii'') became the property of the Roman state. Some would be allocated to the members of a new Roman or Latin colony. Some would be held as '' ager publicus'' (state-owned land) and rented out to Roman tenant-farmers. The rest would be returned to the defeated enemy in return for the latter's adherence to the Roman military alliance. The 19 Latin colonies founded in the period 338–263 outnumbered the Roman ones by four to one. This is because they involved a mixed Roman/original Latin/Italian allied population, and so could more easily attract the necessary number of settlers. But because of the mix, the settlers did not hold citizenship (the Romans among them lost their full citizenship). Instead, they were granted the ''iura Latina'' ("Latin rights") held by original Latins before their incorporation into the citizen body. In essence, these rights were similar to the ''civitates sine suffragio'', except that the Latin colonists were technically not citizens, but ''peregrini

In the early Roman Empire, from 30 BC to AD 212, a ''peregrinus'' (Latin: ) was a free provincial subject of the Empire who was not a Roman citizen. ''Peregrini'' constituted the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants in the 1st and 2nd centur ...

'' ("foreigners"), although they could recover their citizenship by returning to Roman territory. The question arises as to why the Latin colonists were not simply accorded citizenship ''sine suffragio''. The answer is probably for reasons of military security. Classified as non-citizens, the Latins served in the allied ''alae'', not the legions. There they could act as loyal "watchdogs" on potentially treacherous Italian ''socii'', while the Romans/original Latins performed the same function in the legions on their ''sine suffragio'' colleagues.

The post-338 Latin colonies comprised 2,500–6,000 adult male settlers (average 3,700) based on an urban centre with a ''territorium'' of an average size of 370 km2. The ''territorium'' would frequently consist of some of the defeated people's best agricultural land, since the social function of colonies was to satisfy the Romans' land-hungry peasantry. But the choice of site for a ''colonia'' was primarily dictated by strategic considerations. ''Coloniae'' were situated at key geographical points: the coasts (e.g. Antium, Ariminum

Rimini ( , ; rgn, Rémin; la, Ariminum) is a city in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy and capital city of the Province of Rimini. It sprawls along the Adriatic Sea, on the coast between the rivers Marecchia (the ancient ''Ariminus ...

), the exits to mountain passes ( Alba Fucens), major road intersections ( Venusia) and river fords ( Interamna). Also colonies would be sited to provide a defensive barrier between Rome and her allies and potential enemies, as well as to separate those enemies from each other and keep watch on their activity: a divide-and-rule strategy. Thus Rome's string of colonies and eventual annexation of a belt of territory across the centre of the Italian peninsula was driven by the strategic aim of separating the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

from the Samnites and interdicting a potential coalition of these powerful nations.

(c) However, the Romans generally did not annex the whole of the conquered enemy territory, but only selected portions. The defeated peoples generally retained the major part of their territory and their political autonomy. Their sovereignty was only limited in the fields of military and foreign policy, by a treaty with Rome which often varied in detail but always required them to provide troops to serve under Roman command and to "have the same friends and enemies as Rome" (in effect prohibiting them from waging war on other ''socii'' and from conducting independent diplomacy). In some cases, no territory was annexed. For example, after the defeat of Pyrrhus in 275 BC, the Greek city-states of the South were accepted as Roman allies without any loss of territory regardless of whether they had backed Pyrrhus. This was due to the Romans' admiration of Greek culture and the fact that most of the cities contained pro-Roman aristocracies whose interests coincided with the Romans'. By the brutal standards of pre-hegemonic Italy, therefore, the Romans were relatively generous to their defeated foes, a further reason for their success.

A good case-study of how the Romans employed sophisticated divide-and-rule strategies in order to control potentially dangerous enemies is the political settlement imposed on the Samnites after three gruelling wars. The central aim was to prevent a restoration of the Samnite League, a confederation of these warlike tribes which had proved hugely dangerous. After 275 BC, the League's territory was split into three independent cantons: Samnium, Hirpinum and Caudium. A broad belt of Samnite territory was annexed, separating the Samnites from their neighbours to the north - the Marsi

The Marsi were an Italic people of ancient Italy, whose chief centre was Marruvium, on the eastern shore of Lake Fucinus (which was drained for agricultural land in the late 19th century). The area in which they lived is now called Marsica. D ...

and Paeligni. Two Latin colonies were founded in the heart of Samnite territory to act as "watchdogs".

The final feature of Roman hegemony was the construction of a number of paved highways all over the peninsula, revolutionising communication and trade. The most famous and important was the Via Appia, from Rome to Brundisium via Campania (opened 312 BC). Others were the Via Salaria to Picenum, the Via Flaminia from Rome to Arretium (Arezzo), and the Via Cassia into Etruria.

Benefits of Roman hegemony

Incorporation into the Roman military confederation thus entailed significant burdens for the ''socius'': the loss of substantial territory, the loss of freedom of action in foreign relations, heavy military obligations and a complete lack of say in how those military contributions were used. Against these, however, must be set the very important advantages of the system for the ''socii''. By far the most important was the liberation of the ''socii'' from the perpetual intertribal warfare of the pre-hegemonic peninsula. Endemic chaos was replaced by the ''pax Romana''. Each socius' remaining territory was secure from aggression by neighbours. As warfare between ''socii'' was now prohibited, inter-social disputes were settled by negotiation or, ever more frequently, by Roman arbitration. The confederation also acted as the peninsula's defender against external invasion and domination. Gallic invasions from the North were, from 390 BC when the Senones destroyed Rome, seen as the most serious danger and continued into the first century BC. Many were so large that they could only realistically be turned back by a common effort of all Italians, organised by the confederation. The Romans even coined a specific term for such a mobilisation: the ''tumultus Gallicus'', an emergency levy of all able-bodied men, even men over 46 years of age (who were normally exempt from military service). During the third century BC, the confederation successfully repulsed the invasion of Pyrrhus and of Hannibal, which threatened to subject the whole peninsula to Greek and Punic domination respectively. The last such levy was as late as 60 BC, on the eve of Julius Caesar's conquest of Gaul itself. At the same time, the military burden on the ''socii'', though heavy, amounted to only around half that on Roman citizens, since the ''socii'' population outnumbered the Romans by roughly two to one, but normally provided roughly the same number of troops to the confederate levy. During the Samnite Wars, the burden on Romans was extremely onerous. The standard levy was raised from two to four legions and military operations took place every single year. This implies that c. 16% of all Roman adult males spent every campaigning season under arms in this period, rising to 25% during emergencies. Nevertheless, the ''socii'' were allowed to share the spoils of war, the main remuneration of Republican levy soldiers (since pay was minimal), on an equal basis with Roman citizens. This allowed ''socii'' soldiers to return home at the end of each campaigning season with substantial capital and was important in reconciling the ''socii'' to service outside Italy, especially in the second century BC. The Italian allies enjoyed complete autonomy outside the fields of military and foreign policy. They maintained their traditional forms of government, language, laws, taxation and coinage. None were even required to accept a Roman garrison on their territory (except for the special cases of the Greek cities ofTarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Camp ...

, Metapontum and Rhegium

Reggio di Calabria ( scn, label= Southern Calabrian, Riggiu; el, label=Calabrian Greek, Ρήγι, Rìji), usually referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria. It has an estimated popul ...

) at the start of the Second Punic War).

Thus the costs and benefits of membership of the confederation were finely balanced. For some ''socii'', at some periods, primarily the more powerful or aggressive nations that could aspire to Italian hegemony themselves (Samnites, Capua, Tarentum), the costs appeared too high, and these repeatedly took the opportunity to rebel. Others, for whom the benefits of security from aggressive neighbours and external invaders outweighed the burdens, remained loyal.

Military organisation of the Roman alliance

The modern term "Roman confederation" used by some historians to describe the Roman military alliance is misleading, as it implies some form of common political structure, but Rome did it in a way and made it a federation. with a common forum for policy-making, with each constituent of the alliance sending delegates to that forum. Instead, there were no federal political institutions, and indeed not even formal procedures for effective consultation.Staveley (1989) 426 Any ''socius'' that wished to make representations about policy could do so only by despatching an ''ad hoc'' delegation to theRoman Senate

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

. Military and foreign policy lay entirely in the hands of the Roman executive authorities, the Consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

and the policy-making body, the Senate. There existed Italian precedents for a federal political structure e.g. the Latin League and the Samnite League

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they f ...

. But the idea of sharing power with the Latin colonists, let alone the other ''socii'', was anathema to the Roman senatorial elite. Livy relates how after Cannae, as the Senate ranks were depleted by the deaths of 80 senators in the battle, a proposal was put forward that the vacancies should be filled by leaders of the Latin colonies. It was indignantly rejected quasi-unanimously. Livy adds that a similar proposal had been made previously by the Latin colonists themselves, with the same result.

The Roman consular army brought together both Roman and ''socii'' units. For the 250 years between 338 BC and the Social War, legions were always accompanied by allied ''alae'' on campaign. Usually, a consular army would contain an equal number of legions and ''alae'', although, because of variations in the size of the respective units, the ratio of ''socii'' to Romans in a consular army could vary from 2:1 to 1:1, though it was normally closer to the latter.

In most cases, the ''socius sole treaty obligation to Rome was to supply to the confederate army, on demand, a number of fully equipped troops up to a specified maximum each year. The vast majority of ''socii'' were required to supply land troops (both infantry and cavalry), although most of the coastal Greek colonies were '' socii navales'' ("naval allies"), whose obligation was to provide either partly or fully crewed warships to the Roman fleet. Little is known about the size of contingent each ''socius'' was bound to provide, and whether it was proportional to population or wealth.

The confederation did not maintain standing or professional military forces, but levied them, by compulsory conscription, as required for each campaigning season. They would then be disbanded at the end of a conflict. To spread the burden, no man was required to serve more than 16 campaign seasons.

The Roman and allied levies were kept in separate formations. Roman citizens were assigned to the legions, while the Latin and Italian allies were organised into ''alae'' (literally: "wings", because they were always posted on the flanks of the Roman line of battle). A normal consular army would contain two legions and two ''alae'', or about 20,000 men (17,500 infantry and 2,400 cavalry). In times of emergency, a Consul might be authorised to raise a double-strength army of four legions and four ''alae'' e.g. at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC, where each Consul commanded an army of about 40,000 men.

Manpower

Polybius states that the Romans and their allies could draw on a grand total of 770,000 men fit to bear arms (of which 70,000 met the property requirement for cavalry) in 225 BC, shortly before the start of the Second Punic War. The Romans reportedly asked their allies for an urgent register of all "men fit to bear arms" for a ''tumultus Gallicus''. Polybius' subtotals, however, are garbled, as he divides them into two sections, troops actually deployed and those registered as available. It is mostly believed that Polybius' figures refer to adult male ''iuniores'' i.e. persons of military age (16–46 years of age). There are a number of difficulties with Polybius' figures, which are discussed in detail in P. A. Brunt's seminal study, ''Italian Manpower'' (1971): On the basis of Brunt's comments, Polybius' figures may be revised and reorganised as follows: * Campanians were technically Roman citizens ''sine suffragio'', not ''socii''.Historical cohesion of the Roman alliance

This section deals with how successfully the Rome's alliance with the ''socii'' withstood the military challenges it faced in the two and a half centuries of its existence (338–88 BC). The challenges may be divided into three broad periods: (1) 338 to 281 BC, when the confederation was tested mainly by challenges from other Italian powers, especially the Samnites; (2) 281 to 201 BC, when the main threat to the confederation was intervention in Italy by non-Italian powers i.e. Pyrrhus' invasion (281 to 275 BC) and Hannibal's invasion (218 to 203 BC); (3) 201 to 290 when the ''socii'' were called upon to support the Rome's imperialist expansion outside Italy. Elements of all three phases overlap: for example, Gallic invasions of the peninsula from the North recurred throughout the period.Samnite Wars

Phase I (338–281 BC) was dominated by the threeSamnite Wars

The First, Second, and Third Samnite Wars (343–341 BC, 326–304 BC, and 298–290 BC) were fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites, who lived on a stretch of the Apennine Mountains south of Rome and north of the Lucanian tribe ...

, the result of which was the subjugation of the Romans' main military rival on the peninsula, the Samnite league

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they f ...

. The loyalty of the then ''socii'' during this period appears to have remained largely solid. There were sporadic revolts: in 315, 306, 269, and 264 BC by some Campanian cities, the Aurunci

The Aurunci were an Italic tribe that lived in southern Italy from around the 1st millennium BC. They were eventually defeated by Rome and subsumed into the Roman Republic during the second half of the 4th century BC.

Identity

Aurunci is the n ...

, Hernici, and Piceni, respectively. But these were isolated cases and never turned into a general revolt of the ''socii''. Most importantly, when in 297–3 Rome faced its gravest threat in this period, a coalition of Samnites and Gauls, the ''socii'' of the time did not abandon Rome. At the Battle of Sentinum (295), where a huge combined army of Samnites and Gauls suffered a crushing defeat, the ''socii'' contingents actually outnumbered the 18,000 Romans (4 legions deployed).

Pyrrhic War

Phase II (281–203 BC) saw even greater trials of the confederation's cohesion by external invaders with large and sophisticated armies. The intervention in southern Italy of the Epirote king Pyrrhus (281–275 BC), with 25,000 troops, brought the Romans into conflict with a Hellenistic professional army for the first time. Pyrrhus had been invited by Tarentum, which had been alarmed by Roman encroachment in Lucania. The arrival of Pyrrhus triggered a widespread revolt by the southern ''socii'', the Samnites, Lucani and Bruttii. But the revolt was far from universal. The Campanians and Apulians largely remained loyal to Rome. This was probably due to their long-standing antagonism to the Samnites and Tarentines respectively. Neapolis, the key Greek city on the Tyrrhenian, also refused to join Pyrrhus, due to its rivalry with Tarentum. This demonstrates a critical element in the success of Rome's military confederation: the ''socii'' were so divided by mutual antagonisms, often regarding their neighbours as far greater threats than the Romans, that they were never able to stage a universal revolt. The pattern is similar to that of the next great foreign challenge, Hannibal's invasion of Italy (see below). The central Italians (Etruscans and Umbrians) remained loyal, while the southern Italians, with significant exceptions, rebelled. The exceptions were also the similar, save for the Campanians, who joined Hannibal in the later episode. In the event, the Roman forces surprised Pyrrhus by proving a good match for his own, which was unexpected, given that the Romans were temporary levies pitted against professionals. The Romans won one major battle ( Beneventum) and lost two ( Heraclea and Asculum), although in these they inflicted such heavy casualties on the enemy that the term "Pyrrhic victory" was coined. The defeat at Beneventum forced Pyrrhus to withdraw in 275, but it was not until 272 that the rebel ''socii'' were reduced. The surviving accounts for this later phase of the war are thin, but its scale is clear from Rome's celebration of 10 triumphs, each implying the slaughter of at least 5,000 enemy.Second Punic War