Slavery in Canada on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery in Canada includes both that practised by First Nations from earliest times and that under

Slavery in Canada includes both that practised by First Nations from earliest times and that under

While slavery was prohibited in France, it was permitted in its colonies as a means of providing the massive labour force needed to clear land, construct buildings and (in the Caribbean colonies) work on sugar, indigo and tobacco plantations. The 1685 ''

While slavery was prohibited in France, it was permitted in its colonies as a means of providing the massive labour force needed to clear land, construct buildings and (in the Caribbean colonies) work on sugar, indigo and tobacco plantations. The 1685 ''

While many black people who arrived in Nova Scotia during the American Revolution were free, others were not. Some blacks arrived in Nova Scotia as the property of

While many black people who arrived in Nova Scotia during the American Revolution were free, others were not. Some blacks arrived in Nova Scotia as the property of

During the early to mid-19th century, the

During the early to mid-19th century, the

Nova Scotia Historical Society

Runaway Slave advertisement 1772, Nova Scotia

History of Slavery in Canada Portal

{{North America topic, Slavery in Economic history of Canada Legal history of Canada History of Black people in Canada History of human rights in Canada Slavery in the British Empire

Slavery in Canada includes both that practised by First Nations from earliest times and that under

Slavery in Canada includes both that practised by First Nations from earliest times and that under European colonization

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense be ...

.

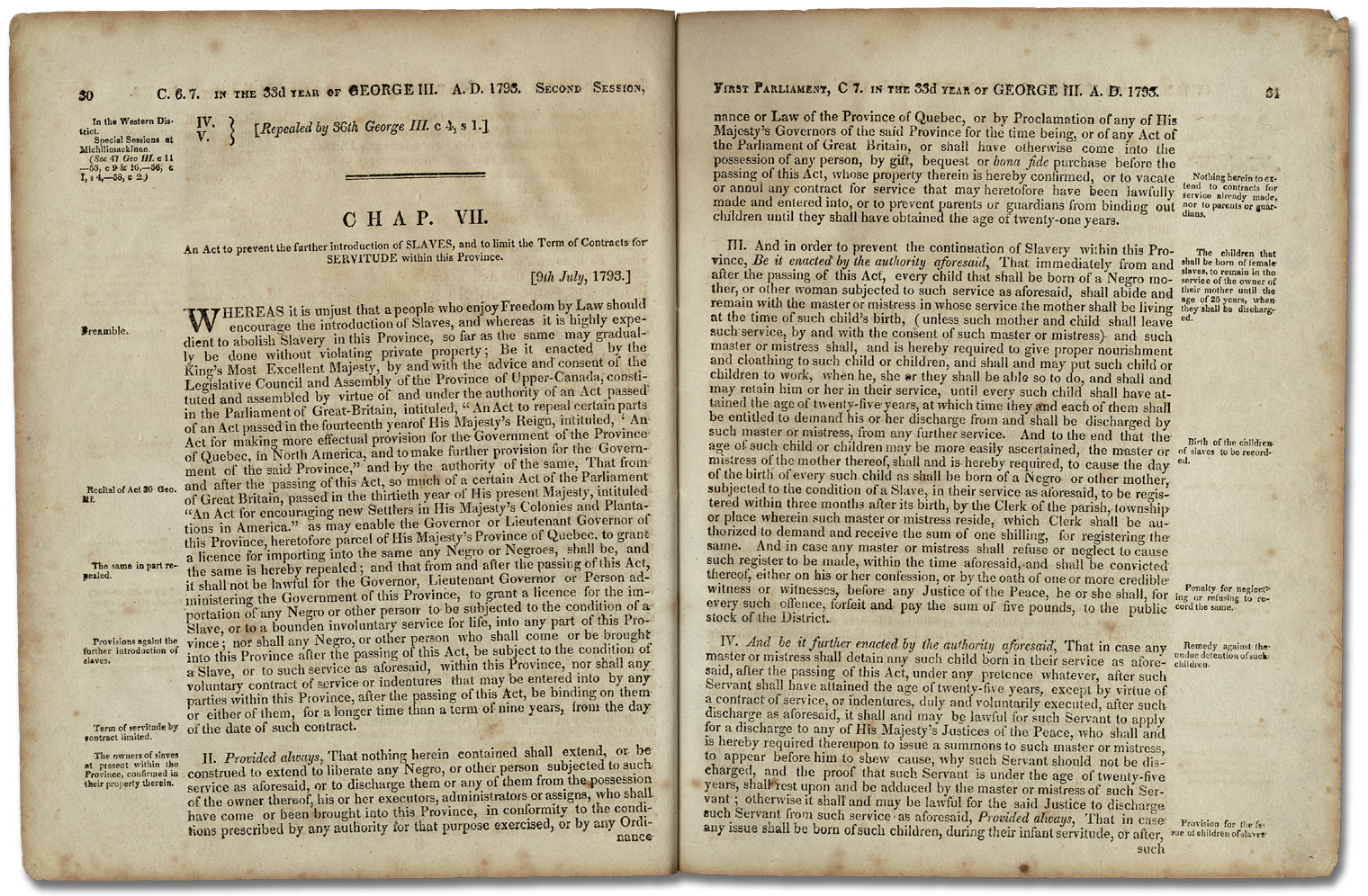

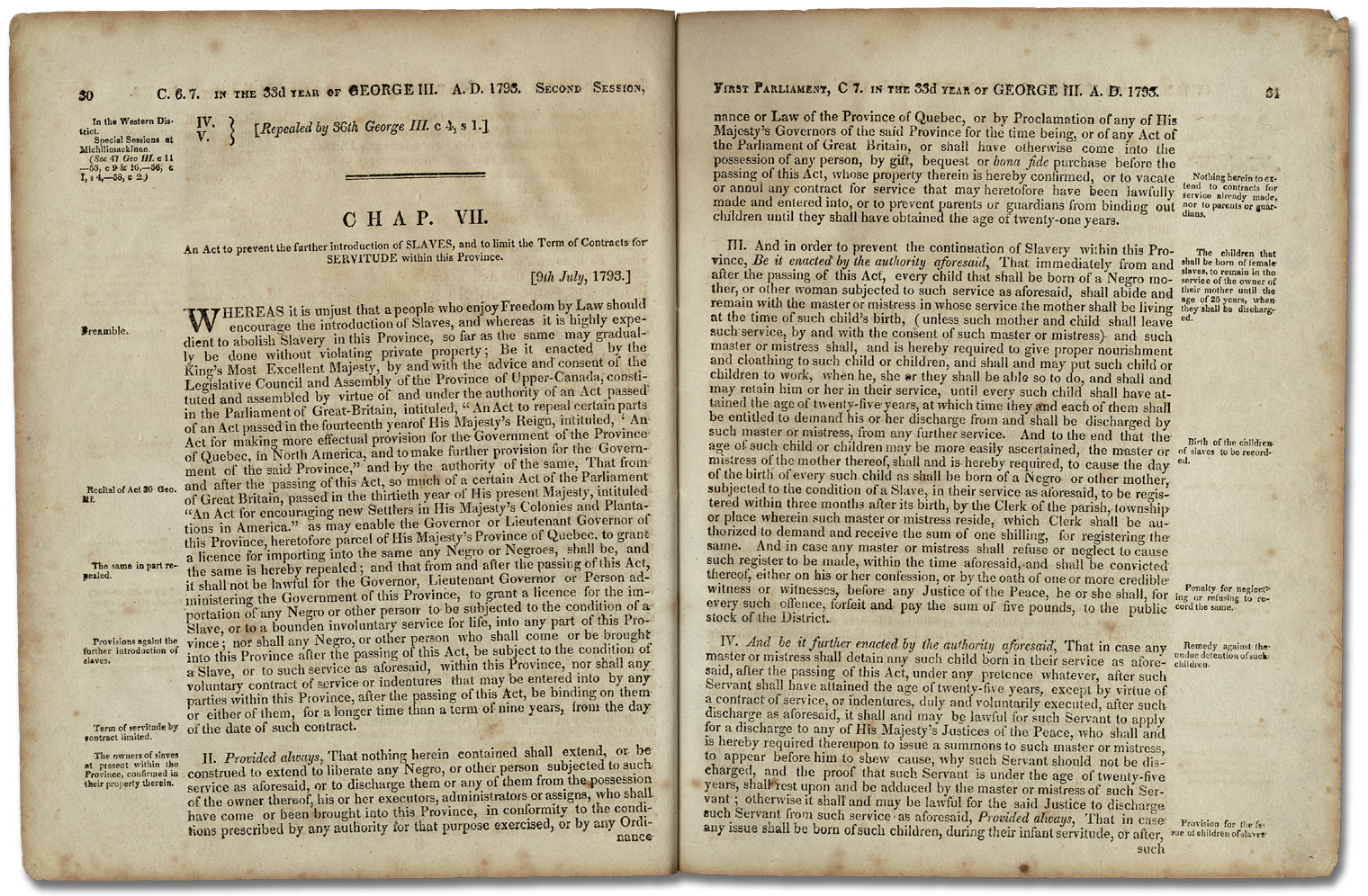

Britain banned the institution of slavery in present-day Canada (and British colonies) in 1833, though the practice of slavery in Canada had effectively ended already early in the 19th century through local statutes and court decisions resulting from litigation on behalf of enslaved people seeking manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

. The courts, to varying degrees, rendered slavery unenforceable in both Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec ...

and Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. In Lower Canada, for example, after court decisions in the late 1790s, the "slave could not be compelled to serve longer than he would, and ... might leave his master at will." Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North Americ ...

passed the Act Against Slavery in 1793, one of the earliest anti-slavery acts in the world.

As slavery in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

continued until 1865 with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, black people (free and enslaved) began immigrating to Canada from the United States after the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

and again after the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, many by way of the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

.

Because Canada's role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

was comparatively limited, the history of Black slavery in Canada is often overshadowed by the more tumultuous slavery practised elsewhere in the Americas.

Under indigenous rule

Slave-owning people of what became Canada were, for example, the fishing societies, such as the Yurok, that lived along the Pacific coast from Alaska to California, on what is sometimes described as the Pacific or Northern Northwest Coast. Some of theindigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast

The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast are composed of many nations and tribal affiliations, each with distinctive cultural and political identities. They share certain beliefs, traditions and practices, such as the centrality of sal ...

, such as the Haida

Haida may refer to:

Places

* Haida, an old name for Nový Bor

* Haida Gwaii, meaning "Islands of the People", formerly called the Queen Charlotte Islands

* Haida Islands, a different archipelago near Bella Bella, British Columbia

Ships

* , a ...

and Tlingit

The Tlingit ( or ; also spelled Tlinkit) are indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their language is the Tlingit language (natively , pronounced ),

, were traditionally known as fierce warriors and slave-traders, raiding as far as California. Slavery was hereditary, the slaves being prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

and their descendants were slaves. Some nations in British Columbia continued to segregate and ostracize the descendants of slaves as late as the 1970s.

Among a few Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Thou ...

nations about a quarter of the population were slaves. One slave narrative was composed by an Englishman, John R. Jewitt

John Rodgers Jewitt (21 May 1783 – 7 January 1821) was an English armourer who entered the historical record with his memoirs about the 28 months he spent as a captive of Maquinna of the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people on what is now the Britis ...

, who had been taken alive when his ship was captured in 1802; his memoir provides a detailed look at life as a slave, and asserts that a large number were held.

Under European colonization

The historian Marcel Trudel estimates that there were fewer than 4,200 slaves in the area ofCanada (New France)

The colony of Canada was a French colony within the larger territory of New France. It was claimed by France in 1535 during the second voyage of Jacques Cartier, in the name of the French king, Francis I. The colony remained a French territory u ...

and later The Canadas

The Canadas is the collective name for the provinces of Lower Canada and Upper Canada, two historical British colonies in present-day Canada. The two colonies were formed in 1791, when the British Parliament passed the '' Constitutional Act'', ...

between 1671 and 1831.

Around two-thirds of these slaves were of indigenous ancestry

(2,700 typically called '' panis'', from the French term for Pawnee) and one third were of African descent (1,443). They were house servants and farm workers. The number of Black slaves increased during British rule, especially with the arrival of United Empire Loyalists

United Empire Loyalists (or simply Loyalists) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec, and Governor General of The Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America dur ...

after 1783. The Maritimes

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of C ...

saw 1,200 to 2,000 slaves arrive prior to abolition, with 300 accounted for in Lower Canada, and between 500 and 700 in Upper Canada. A small portion of Black Canadians

Black Canadians (also known as Caribbean-Canadians or Afro-Canadians) are people of full or partial sub-Saharan African descent who are citizens or permanent residents of Canada. The majority of Black Canadians are of Caribbean origin, though ...

today are descended from these slaves.

People of African descent were forcibly captured by local chiefs as chattel slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and sold to traders bound for southern areas of the Americas. Those in what is now called Canada typically came from the American colonies, as no shiploads of human chattel went to Canada directly from Africa. There were no large plantations in Canada, and therefore no demand for a large slave work force of the sort that existed in most European colonies in the Americas. Nevertheless, slaves in Canada were subjected to the same physical, psychological, and sexual violence and punishments as their American counterparts.

Under French rule

Under French rule, enslaved First Nations people outnumbered enslaved individuals of African descent. According to Afua Cooper, author of "The Hanging of Angélique: The Untold Story of Canadian Slavery and the Burning of Old Montréal", this was due to the relative ease with which New France could acquire First Nations slaves. She noted that the mortality of slaves was high, with the average age of First Nations slaves only 17, and the average age of slaves of African descent, 25. One of the first recorded Black slaves in Canada was brought by a British convoy to New France in 1628. Olivier le Jeune was the name given to the boy, originally fromMadagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

.

By 1688, New France's population was 11,562 people, made up primarily of fur traders, missionaries, and farmers settled in the St. Lawrence Valley. To help overcome its severe shortage of servants and labourers, King Louis XIV granted New France's petition to import Black slaves from West Africa. Though no shipments ever arrived from Africa, colonists did acquire some Black slaves from other French and British colonies. From the late 1600s, they also acquired Indigenous slaves, mostly from what is now the US Midwestern states, through their western fur-trade networks. Slaves of Indigenous origin were called "Panis," but few came from the Pawnee tribe. More commonly, they were of Fox, Dakota, Iowa and Apache origin, captives taken in war by Indigenous allies and trading partners of the French.

While slavery was prohibited in France, it was permitted in its colonies as a means of providing the massive labour force needed to clear land, construct buildings and (in the Caribbean colonies) work on sugar, indigo and tobacco plantations. The 1685 ''

While slavery was prohibited in France, it was permitted in its colonies as a means of providing the massive labour force needed to clear land, construct buildings and (in the Caribbean colonies) work on sugar, indigo and tobacco plantations. The 1685 ''Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by the French King Louis XIV in 1685 defining the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire. The decree restricted the activities of free people of color, mandated the conversion of all e ...

'' set the pattern for policing slavery in the West Indies. It required that all slaves be instructed as Catholics and not as Protestants. It concentrated on defining the condition of slavery, and established harsh controls. Slaves had virtually no rights, though the Code did enjoin masters to take care of the sick and old. The ''Code noir'' does not seem to have applied to Canada and so, in 1709, the intendant Jacques Raudot

Jacques Raudot (1638 - 20 February 1728, Paris) was the co-Intendant of New France between 1705 and 1710 with his son Antoine-Denis Raudot.

In 1709 Raudot issued an ordinance to clarify whether individuals could legally own slaves, in New Fra ...

issued an ordinance officially recognizing slavery in New France; slavery existed before that date, but only as of 1709 was it instituted in law.

One slave is well-recorded in the history of Montreal: Marie-Joseph Angélique

Marie-Josèphe dite Angélique (died June 21, 1734) was the name given to a Portuguese-born black slave in New France (later the province of Quebec in Canada) by her last owners. She was tried and convicted of setting fire to her owner's home, bu ...

was held in slavery by a rich widow in that city. In 1734, after learning that she was going to be sold and separated from her lover, Angélique set fire to her owner's house and escaped. The fire raged out of control, destroying forty-six buildings. Captured two months later, Angélique was paraded through the city, then tortured until she confessed her crime. In the afternoon of the day of execution, Angélique was taken through the streets of Montreal and, after the stop at the church for her '' amende honorable'', made to climb a scaffold facing the ruins of the buildings destroyed by the fire. There she was hanged until dead, with her body flung into the fire and the ashes scattered in the wind.

Historian Marcel Trudel recorded approximately 4,000 slaves by the end of New France in 1759, of which 2,472 were Aboriginal people, and 1,132 Blacks. After the Conquest of New France

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, ...

by the British, slave ownership remained dominated by the French. Trudel identified 1,509 slave owners, of which only 181 were English. Trudel also noted 31 marriages took place between French colonists and Aboriginal slaves.

Under British rule

First Nations owned or traded in slaves, an institution that had existed for centuries or longer among certain groups. Shawnee, Potawatomi, and other western tribes imported slaves from Ohio and Kentucky and sold or gifted them to allies and Canadian settlers. Mohawk Chief Thayendenaga (a.k.a.Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York, who was closely associated with Great Britain during and after the American Revolution. Perhaps ...

) used black people he had captured during the American Revolution to build Brant House at Burlington Beach and a second home near Brantford. In all, Brant owned about forty black slaves.

Black slaves lived in the British regions of Canada in the 18th century—104 were listed in a 1767 census of Nova Scotia, but their numbers were small until the United Empire Loyalist

United Empire Loyalists (or simply Loyalists) is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec, and Governor General of The Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America ...

influx after 1783. As white Loyalists fled the new American Republic, they took with them about 2,000 black slaves: 1,200 to the Maritimes (Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

, and Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

), 300 to Lower Canada (Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

), and 500 to Upper Canada (Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

). In Ontario, the Imperial Act of 1790 assured prospective immigrants that their slaves would remain their property. As under French rule, Loyalist slaves were held in small numbers and were employed as domestic servants, farm hands, and skilled artisans.

Following the Battle of the Plains of Abraham

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille des Plaines d'Abraham, Première bataille de Québec), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe ...

and the British conquest of New France, the subject of slavery in Canada is unmentioned—neither banned nor permitted—in both the 1763 Treaty of Paris and the Quebec Act of 1774 or the Treaty of Paris of 1783.

The system of gang labour, and its consequent institutions of control and brutality, did not develop in Canada as it did in the USA. Because they did not appear to pose a threat to their masters, slaves were permitted to learn to read and write, Christian conversion was encouraged, and their marriages were recognized by law. Death rates among slaves were nevertheless high, confirming the brutal nature of the slave regime.

The ''Quebec Gazette'' of 12 July 1787 had an advertisement:

Abolition movement

Lower Canada (Quebec)

In Lower Canada, SirJames Monk

Sir James Monk (1745 – November 18, 1826) was Chief Justice of Lower Canada. Monk played a significant role in the abolition of slavery in British North America, when as Chief Justice he rendered a series of decisions regarding escaped ...

, the Chief Justice, rendered a series of decisions in the late 1790s that undermined the ability to compel slaves to serve their masters; while "not technically abolishing slavery, hey

Hey or Hey! may refer to:

Music

* Hey (band), a Polish rock band

Albums

* ''Hey'' (Andreas Bourani album) or the title song (see below), 2014

* ''Hey!'' (Julio Iglesias album) or the title song, 1980

* ''Hey!'' (Jullie album) or the title ...

rendered it innocuous." As a result, slaves began to flee their masters within the province, but also from other provinces and from the United States. This occurred several years before the legislature acted in Upper Canada to limit slavery. While the decision was founded upon a technicality (the extant law allowing committal of slaves not to jails, but only to houses of correction, of which there were none in the province), Monk went on to say that "slavery did not exist in the province and to warn owners that he would apply this interpretation of the law to all subsequent cases." In subsequent decisions, and in the absence of specific legislation, Monk's interpretation held (even once there had been houses of correction established). In a later test of this interpretation, the administrator of Lower Canada, Sir James Kempt, refused in 1829 a request from the U.S. government to return an escaped slave, informing that fugitives might be given up only when the crime in question was also a crime in Lower Canada: "The state of slavery is not recognized by the Law of Canada. ... Every Slave therefore who comes into the Province is immediately free whether he has been brought in by violence or has entered it of his own accord."

Nova Scotia

While many black people who arrived in Nova Scotia during the American Revolution were free, others were not. Some blacks arrived in Nova Scotia as the property of

While many black people who arrived in Nova Scotia during the American Revolution were free, others were not. Some blacks arrived in Nova Scotia as the property of white American

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

Loyalists. In 1772, prior to the American Revolution, Britain outlawed the slave trade in the British Isles followed by the Knight v. Wedderburn

Joseph Knight (''fl.'' 1769–1778) was a man born in Guinea (the general name of West Africa) and there seized into slavery. It appears that the captain of the ship which brought him to Jamaica there sold him to John Wedderburn of Ballindean, S ...

decision in Scotland in 1778. This decision, in turn, influenced the colony of Nova Scotia. In 1788, abolitionist James Drummond MacGregor

Rev. James Drummond MacGregor ( gd, an t-Urr. Seumas MacGriogar) (December 1759 – 3 March 1830) was an author of Christian poetry in both Scottish and Canadian Gaelic, an abolitionist and Presbyterian minister in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Life and ...

from Pictou published the first anti-slavery literature in Canada and began purchasing slaves' freedom and chastising his colleagues in the Presbyterian church who owned slaves. Historian Alan Wilson describes the document as "a landmark on the road to personal freedom in province and country". Historian Robin Winks writes it is "the sharpest attack to come from a Canadian pen even into the 1840s; he had also brought about a public debate which soon reached the courts". (Abolitionist lawyer Benjamin Kent was buried in Halifax in 1788.) In 1790 John Burbidge

John Burbidge (c.1718 – March 11, 1812) was a soldier, land owner, judge and political figure in Nova Scotia. He was a member of the 1st General Assembly of Nova Scotia in 1758 and represented Halifax Township from 1759 to 1765 and Cornwa ...

freed his slaves. Led by Richard John Uniacke

Richard John Uniacke (November 22, 1753 – October 11, 1830) was an abolitionist, lawyer, politician, member of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly and Attorney General of Nova Scotia. According to historian Brian Cutherburton, Uniacke was "t ...

, in 1787, 1789 and again on 11 January 1808 the Nova Scotian legislature refused to legalize slavery. Two chief justices, Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange

Sir Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange (30 November 1756 – 16 July 1841) was a chief justice in Nova Scotia, known for waging "judicial war" to free Black Nova Scotian slaves from their owners. From 1789 to 1797, he was the sixth Chief Justice ...

(1790–1796) and Sampson Salter Blowers

Sampson Salter Blowers (March 10, 1742 – October 25, 1842) was a noted North American lawyer, Loyalist and jurist from Nova Scotia who, along with Chief Justice Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange, waged "judicial war" in his efforts to free B ...

(1797–1832), were instrumental in freeing slaves from their owners in Nova Scotia. They were held in high regard in the colony. Justice Alexander Croke

Sir Alexander Croke (July 22, 1758 – December 27, 1842) was a British judge, colonial administrator and author influential in Nova Scotia of the early nineteenth century.

Life

Croke was born in Aylesbury, England, to a wealthy family and at ...

(1801–1815) also impounded American slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

s during this time period (the most famous being the Liverpool Packet

''Liverpool Packet'' was a privateer schooner from Liverpool, Nova Scotia, that captured 50 American vessels in the War of 1812. American privateers captured ''Liverpool Packet'' in 1813, but she failed to take any prizes during the four months bef ...

). During the war, Nova Scotian Sir William Winniett

Sir William Robert Wolseley Winniett (b. 2 March 1793, Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. - d. 4 Dec. 1850, Accra - Ghana) was the Governor General of Gold Coast at Cape Coast Castle (Ghana). He worked to abolish the slave trade on the Slave Coast of ...

served as a crew on board HMS Tonnant in the effort to free slaves from America. (As the Governor of the Gold Coast, Winniett would later also work to end the slave trade in Western Africa.) By the end of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

and the arrival of the Black Refugees, there were few slaves left in Nova Scotia. (The Slave Trade Act

Slave Trade Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States that relates to the slave trade.

The "See also" section lists other Slave Acts, laws, and international conventions which developed the c ...

outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 outlawed slavery altogether.)

The Sierra Leone Company

The Sierra Leone Company was the corporate body involved in founding the second British colony in Africa on 11 March 1792 through the resettlement of Black Loyalists who had initially been settled in Nova Scotia (the Nova Scotian Settlers) aft ...

was established to relocate groups of formerly enslaved Africans, nearly 1,200 black Nova Scotians, most of whom had escaped enslavement in the United States. Given the coastal environment of Nova Scotia, many had died from the harsh winters. They created a settlement in the existing colony in Sierra Leone (already established to make a home for the "poor blacks" of London) at Freetown in 1792. Many of the "black poor" included other African and Asian inhabitants of London. The Freetown settlement was joined, particularly after 1834, by other groups of freed Africans and became the first African-American haven in Africa for formerly enslaved Africans.

Upper Canada (Ontario)

By 1790 the abolition movement was gaining credence in Canada and the ill intent of slavery was evidenced by an incident involving a slave woman being violently abused by her slave owner on her way to being sold in the United States. In 1793 Chloe Cooley, in an act of defiance yelled out screams of resistance. The abuse committed by her slave owner and her violent resistance was witnessed by Peter Martin and William Grisely. Peter Martin, a former slave, brought the incident to the attention ofLieutenant Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. He founded Yor ...

. Under the auspices of Simcoe, the '' Act Against Slavery'' of 1793 was legislated. The elected members of the executive council, many of whom were merchants or farmers who depended on slave labour, saw no need for emancipation. Attorney-General John White later wrote that there was "much opposition but little argument" to his measure. Finally the Assembly passed the ''Act Against Slavery'' that legislated the gradual abolition of slavery: no slaves could be imported; slaves already in the province would remain enslaved until death, no new slaves could be brought into Upper Canada, and children born to female slaves would be slaves but must be freed at age 25. To discourage manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

, the Act required the master to provide security that the former slave would not become a public charge. The compromise ''Act Against Slavery'' stands as the only attempt by any Ontario legislature to act against slavery. This legal rule ensured the eventual end of slavery in Upper Canada, although as it diminished the sale value of slaves within the province it also resulted in slaves being sold to the United States. In 1798 there was an attempt by lobby groups to rectify the legislation and import more slaves. Slaves discovered they could gain freedom by escaping to Ohio and Michigan in the United States.

By 1800 the other provinces of British North America had effectively limited slavery through court decisions requiring the strictest proof of ownership, which was rarely available. In 1819, John Robinson John Robinson may refer to:

Academics

*John Thomas Romney Robinson (1792–1882), Irish astronomer and physicist

* John J. Robinson (1918–1996), historian and author of ''Born in Blood''

* John Talbot Robinson (1923–2001), paleontologist

*Joh ...

, Attorney General of Upper Canada, declared that by residing in Canada, black residents were set free, and that Canadian courts would protect their freedom.

Slavery remained legal, however, until the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

's Slavery Abolition Act finally abolished slavery in most parts of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

effective 1 August 1834.

Underground Railroad

During the early to mid-19th century, the

During the early to mid-19th century, the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

network was established in the United States to free slaves, by bringing them to locations where the slaves would be free from being re-captured. British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

, now known as Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, was a major destination of the Underground Railroad. The Canadian public's awareness of slavery in Canada is typically limited to the Underground Railroad, which is the only education relating to the history of slavery that school children typically receive.

In Nova Scotia, former slave Richard Preston

Richard Preston (born August 5, 1954) is a writer for ''The New Yorker'' and bestselling author who has written books about infectious disease, bioterrorism, redwoods and other subjects, as well as fiction.

Biography

Preston was born in Cambri ...

established the African Abolition Society in the fight to end slavery in America. Preston was trained as a minister in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

and met many of the leading voices in the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

movement that helped to get the Slavery Abolition Act passed by the British Parliament in 1833. When Preston returned to Nova Scotia, he became the president of the Abolitionist movement in Halifax.

Preston stated:

There are slave cemeteries in parts of Canada, in various states of condition, some neglected and abandoned. They include cemeteries in St-Armand, Quebec; Shelburne, Nova Scotia; and Priceville and Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

in Ontario.

Modern slavery

The ratifying of the Slavery Convention by Canada in 1953 began the country's international commitments to address modern slavery. Human trafficking in Canada is a legal and political issue, and Canadian legislators have been criticized for having failed to deal with the problem in a more systematic way.British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

's Office to Combat Trafficking in Persons

The Office to Combat Trafficking in Persons (OCTIP) is a government agency responsible for coordinating efforts to address human trafficking in British Columbia, Canada. The focus of OCTIP's mandate is human rights, specifically those of the vic ...

formed in 2007, making British Columbia the first province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

to address human trafficking in a formal manner. The biggest human trafficking case in Canadian history

The history of Canada covers the period from the arrival of the Paleo-Indians to North America thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day Canada were inhabited for millennia by ...

surrounded the dismantling of the Domotor-Kolompar criminal organization. On June 6, 2012, the Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown-i ...

established the National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking

The National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking is a four-year action plan that was established by the Government of Canada on June 6, 2012 to oppose human trafficking in Canada. In 2004, the government's Interdepartmental Working Group ...

in order to oppose human trafficking

Human trafficking is the trade of humans for the purpose of forced labour, sexual slavery, or commercial sexual exploitation for the trafficker or others. This may encompass providing a spouse in the context of forced marriage, or the extr ...

. The Human Trafficking Taskforce was established in June 2012 to replace the Interdepartmental Working Group on Trafficking in Persons as the body responsible for the development of public policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to solve or address relevant and real-world problems, guided by a conception and often implemented by programs. Public ...

related to human trafficking in Canada.

One current and highly publicized instance is the vast disappearances of Aboriginal women which has been linked to human trafficking by some sources. Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper

Stephen Joseph Harper (born April 30, 1959) is a Canadian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Canada from 2006 to 2015. Harper is the first and only prime minister to come from the modern-day Conservative Party of Canada, ...

had been reluctant to tackle the issue on the grounds that it is not a "sociological issue" and declined to create a national inquiry into the issue counter to United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

and Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (the IACHR or, in the three other official languages Spanish, French, and Portuguese CIDH, ''Comisión Interamericana de los Derechos Humanos'', ''Commission Interaméricaine des Droits de l'Homme'' ...

' opinions that the issue is significant and in need of higher inquiry.

See also

*Marie-Joseph Angélique

Marie-Josèphe dite Angélique (died June 21, 1734) was the name given to a Portuguese-born black slave in New France (later the province of Quebec in Canada) by her last owners. She was tried and convicted of setting fire to her owner's home, bu ...

* Marguerite Duplessis

* History of slavery

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and religions from ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The social, economic, and legal positions of e ...

* Human rights in Canada

Human rights in Canada have come under increasing public attention and legal protection since World War II. Prior to that time, there were few legal protections for human rights. The protections which did exist focused on specific issues, rather t ...

* History of slavery in Louisiana Following Robert Cavelier de La Salle establishing the French claim to the territory and the introduction of the name ''Louisiana'', the first settlements in the southernmost portion of Louisiana (New France) were developed at present-day Biloxi ( ...

* Turner Chapel, Oakville's Black church

* ''R v Jones'' (New Brunswick)

References

Further reading

* * * Clarke, George Elliott."'This Is No Hearsay': Reading the Canadian Slave Narratives," ''Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada / Cahiers De La Société Bibliographique du Canada'' 2005 43(1): 7–32, original narratives written by Canadian slaves * * * . Winner, 2007 Governor General's Literary Award for Nonfiction; Nominee (Nonfiction), National Books Critics Circle Award 2007. See, Governor General's Award for English language non-fiction. * Hajda, Yvonne P. "Slavery in the Greater Lower Columbia Region," '' Ethnohistory'' 2005 52(3): 563–588, * Henry, Natasha, Emancipation Day: Celebrating Freedom in Canada * inJSTOR

JSTOR (; short for ''Journal Storage'') is a digital library founded in 1995 in New York City. Originally containing digitized back issues of academic journals, it now encompasses books and other primary sources as well as current issues of j ...

*

*

* Whitfield, Harvey. "Black Loyalists and Black Slaves in Maritime Canada," ''History Compass

''History Compass'' is a peer-reviewed online-only academic journal published by Wiley-Blackwell. Originally launched in association with the Institute of Historical Research (London), it is unique in its purpose and structure, aiming to "solve th ...

'' 2007 5(6): 1980-1997,

Nova Scotia Historical Society

External links

Runaway Slave advertisement 1772, Nova Scotia

History of Slavery in Canada Portal

{{North America topic, Slavery in Economic history of Canada Legal history of Canada History of Black people in Canada History of human rights in Canada Slavery in the British Empire