Slavery In Africa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery has historically been widespread in

Slavery has historically been widespread in

Military slavery involved the acquisition and training of conscripted military units which would retain the identity of military slaves even after their service. Slave soldier groups would be run by a ''Patron'', who could be the head of a government or an independent warlord, and who would send his troops out for money and his own political interests.

This was most significant in the Nile valley (primarily in

Military slavery involved the acquisition and training of conscripted military units which would retain the identity of military slaves even after their service. Slave soldier groups would be run by a ''Patron'', who could be the head of a government or an independent warlord, and who would send his troops out for money and his own political interests.

This was most significant in the Nile valley (primarily in

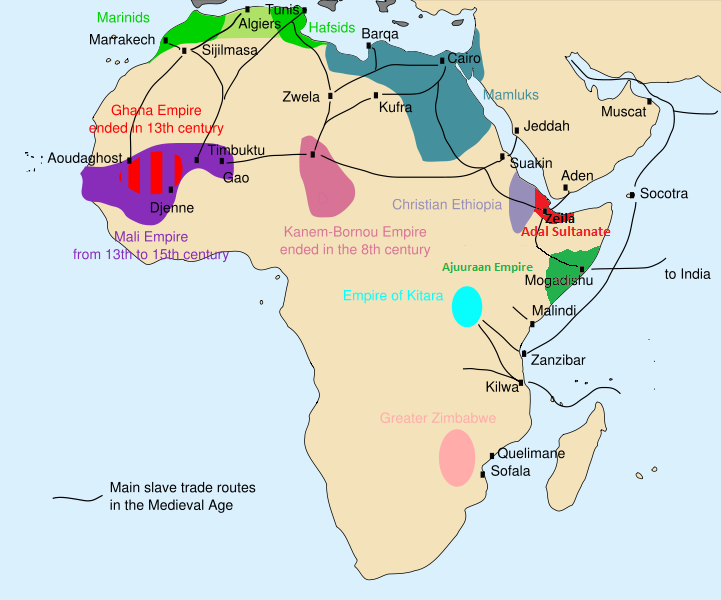

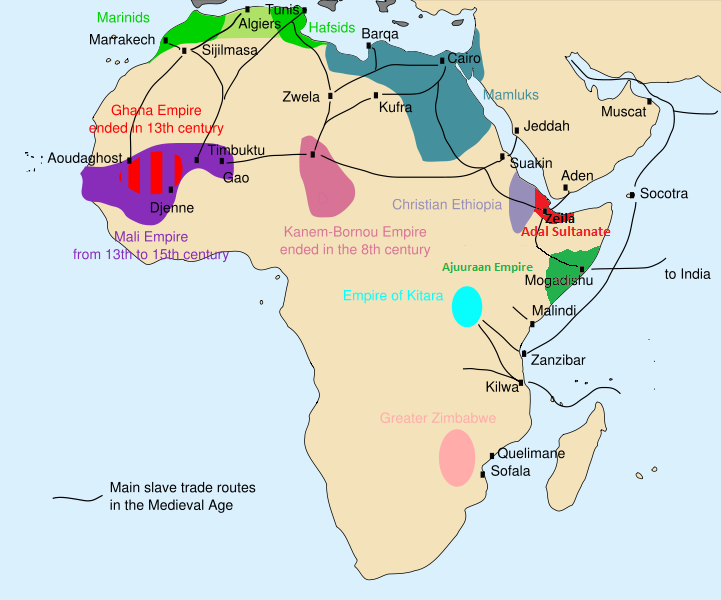

Like most other regions of the world, slavery and forced labour existed in many kingdoms and societies of Africa for hundreds of years. According to Ugo Kwokeji, early European reports of slavery throughout Africa in the 1600s are unreliable because they often conflated various forms of servitude as equal to chattel slavery.

The best evidence of slave practices in Africa come from the major kingdoms, particularly along the coast, and there is little evidence of widespread slavery practices in stateless societies. Slave trading was mostly secondary to other trade relationships; however, there is evidence of a trans- Saharan slave trade route from Roman times which persisted in the area after the fall of the

Like most other regions of the world, slavery and forced labour existed in many kingdoms and societies of Africa for hundreds of years. According to Ugo Kwokeji, early European reports of slavery throughout Africa in the 1600s are unreliable because they often conflated various forms of servitude as equal to chattel slavery.

The best evidence of slave practices in Africa come from the major kingdoms, particularly along the coast, and there is little evidence of widespread slavery practices in stateless societies. Slave trading was mostly secondary to other trade relationships; however, there is evidence of a trans- Saharan slave trade route from Roman times which persisted in the area after the fall of the

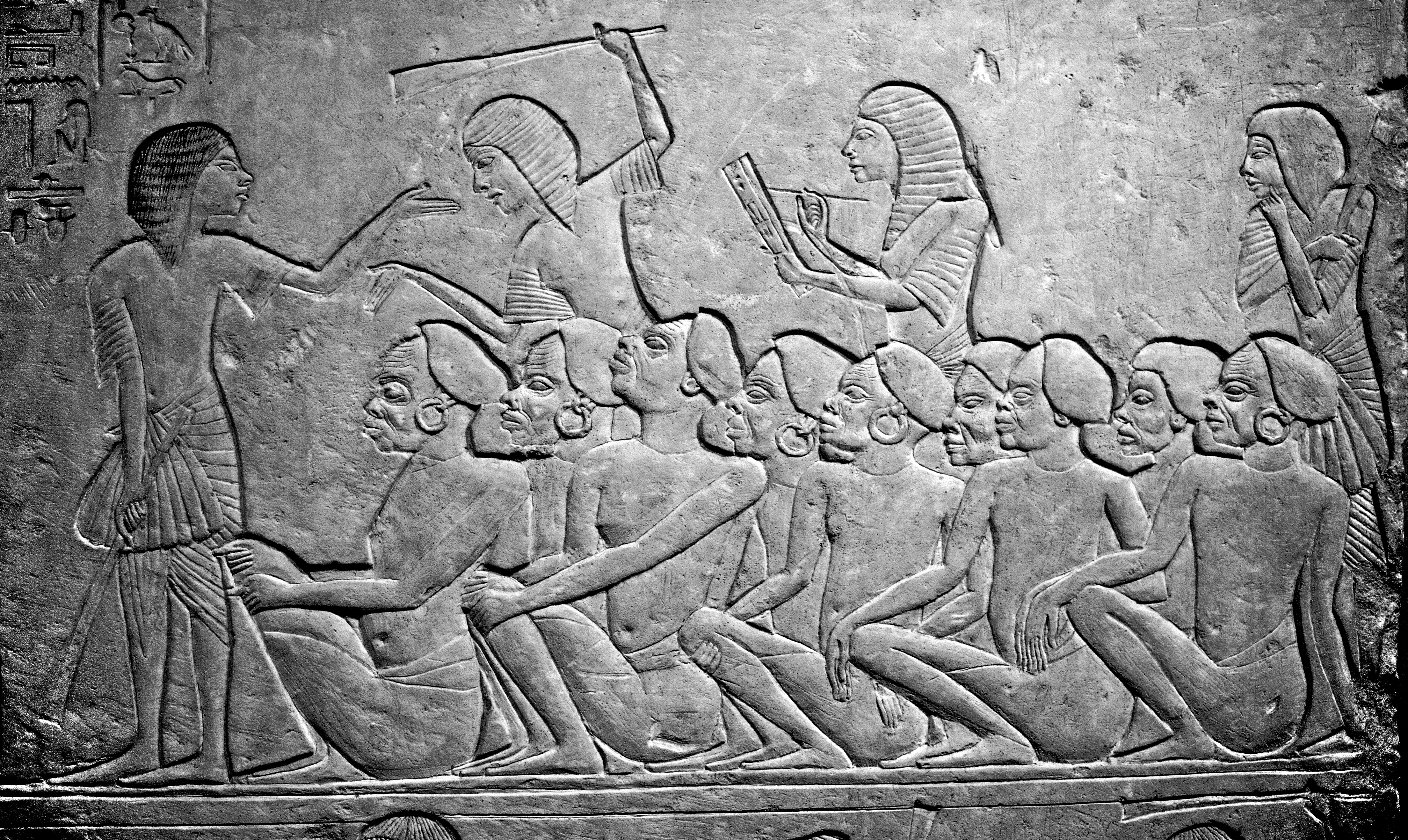

Slavery in northern Africa dates back to ancient Egypt. The

Slavery in northern Africa dates back to ancient Egypt. The

The

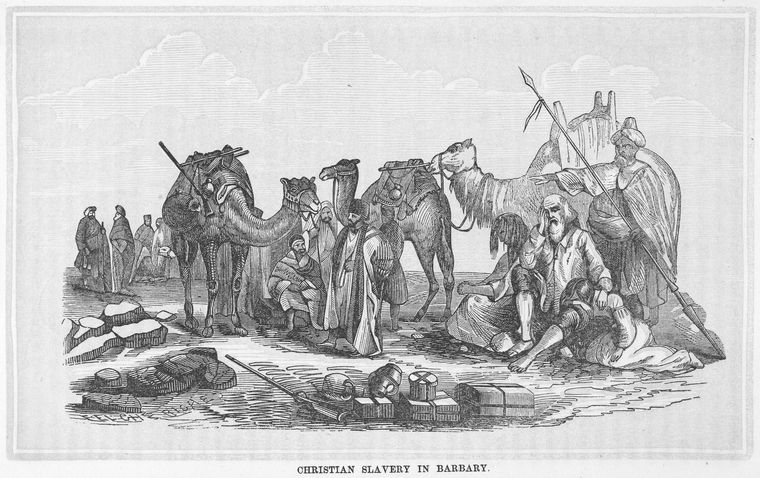

The  Early modern sources are full of descriptions of the sufferings of Christian galley slaves of the

Early modern sources are full of descriptions of the sufferings of Christian galley slaves of the

In the

In the  Slavery, as practiced in

Slavery, as practiced in

Slaves were transported since antiquity along trade routes crossing the Sahara.

Oral tradition recounts slavery existing in the

Slaves were transported since antiquity along trade routes crossing the Sahara.

Oral tradition recounts slavery existing in the

Slavery has historically been widespread in

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. Systems of servitude and slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

were common in parts of Africa in ancient times, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade

During the Trans-Saharan slave trade, slaves were transported across the Sahara desert. Most were moved from Sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa to be sold to Mediterranean and Middle eastern civilizations; a small percentage went the oth ...

, Indian Ocean slave trade and Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

(which started in the 16th century) began, many of the pre-existing local African slave systems began supplying captives for slave market

A slave market is a place where slaves are bought and sold. These markets became a key phenomenon in the history of slavery.

Slave markets in the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire during the mid-14th century, slaves were traded in special ...

s outside Africa. Slavery in contemporary Africa

The continent of Africa is one of the regions most rife with contemporary slavery. Slavery in Africa has a long history, within Africa since before historical records, but intensifying with the trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean slave trade and ag ...

is still practiced despite it being illegal.

In the relevant literature African slavery is categorized into indigenous slavery and export slavery, depending on whether or not slaves were traded beyond the continent.

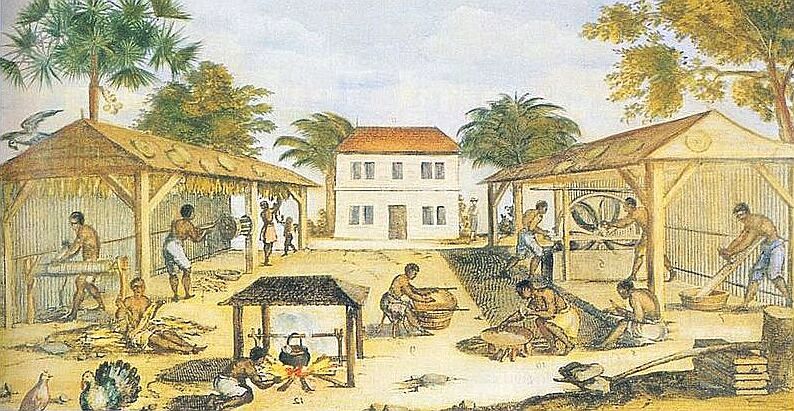

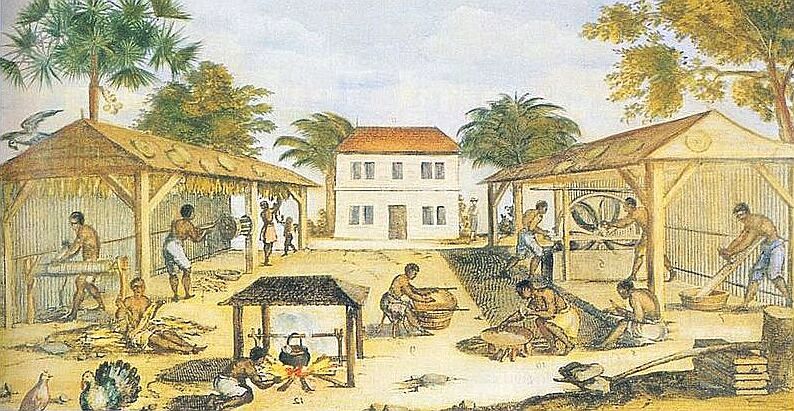

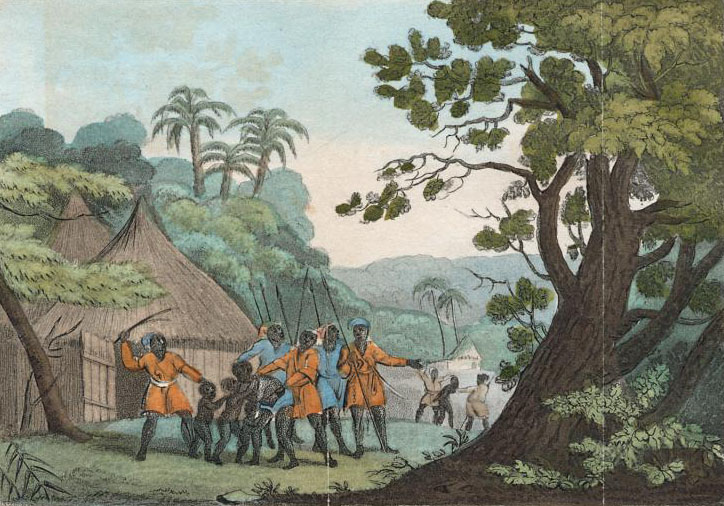

Slavery in historical Africa was practised in many different forms: Debt slavery, enslavement of war captives, military slavery, slavery for prostitution, and enslavement of criminals were all practised in various parts of Africa. Slavery for domestic and court purposes was widespread throughout Africa. Plantation slavery also occurred, primarily on the eastern coast of Africa and in parts of West Africa. The importance of domestic plantation slavery increased during the 19th century, due to the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade. Many African states dependent on the international slave trade reoriented their economies towards legitimate commerce worked by slave labour.

Forms of slavery

Multiple forms ofslavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and servitude have existed throughout African history, and were shaped by indigenous practices of slavery as well as the Roman institution of slavery (and the later Christian views on slavery), the Islamic institutions of slavery via the Muslim slave trade

The history of slavery in the Muslim world began with institutions inherited from pre-Islamic Arabia;Lewis 1994Ch.1 and the practice of keeping slavery, slaves subsequently developed in radically different ways, depending on social-political fac ...

, and eventually the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

. Slavery was a part of the economic structure of African societies for many centuries, although the extent varied. Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berber Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, largely in the Muslim ...

, who visited the ancient kingdom of Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Ma ...

in the mid-14th century, recounts that the local inhabitants vied with each other in the number of slaves and servants they had, and was himself given a slave boy as a "hospitality gift." In sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

, the slave relationships were often complex, with rights and freedoms given to individuals held in slavery and restrictions on sale and treatment by their masters. Many communities had hierarchies between different types of slaves: for example, differentiating between those who had been born into slavery and those who had been captured through war.

The forms of slavery in Africa were closely related to kinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

structures. In many African communities, where land could not be owned, enslavement of individuals was used as a means to increase the influence a person had and expand connections. This made slaves a permanent part of a master's lineage, and the children of slaves could become closely connected with the larger family ties. Children of slaves born into families could be integrated into the master's kinship group and rise to prominent positions within society, even to the level of chief in some instances. However, stigma often remained attached, and there could be strict separations between slave members of a kinship group and those related to the master.

Chattel slavery

Chattel slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to per ...

is a specific servitude relationship where the slave is treated as the property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

of the owner. As such, the owner is free to sell, trade, or treat the slave as he would other pieces of property, and the children of the slave often are retained as the property of the master. There is evidence of long histories of chattel slavery in the Nile River

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

valley, much of the Sahel and North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

. Evidence is incomplete about the extent and practices of chattel slavery throughout much of the rest of the continent prior to written records by Arab or European traders.

Domestic service

Many slave relationships in Africa revolved around domestic slavery, where slaves would work primarily in the house of the master, but retain some freedoms. Domestic slaves could be considered part of the master's household and would not be sold to others without extreme cause. The slaves could own the profits from their labour (whether in land or in products), and could marry and pass the land on to their children in many cases.Pawnship

Pawnship

Debt bondage, also known as debt slavery, bonded labour, or peonage, is the pledge of a person's services as security for the repayment for a debt or other obligation. Where the terms of the repayment are not clearly or reasonably stated, the pe ...

, or debt bondage slavery, involves the use of people as collateral to secure the repayment of debt

Debt is an obligation that requires one party, the debtor, to pay money or other agreed-upon value to another party, the creditor. Debt is a deferred payment, or series of payments, which differentiates it from an immediate purchase. The ...

. Slave labour is performed by the debtor

A debtor or debitor is a legal entity (legal person) that owes a debt to another entity. The entity may be an individual, a firm, a government, a company or other legal person. The counterparty is called a creditor. When the counterpart of this ...

, or a relative of the debtor (usually a child). Pawnship was a common form of collateral in West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

. It involved the pledge

Pledge may refer to:

Promises

* a solemn promise

* Abstinence pledge, a commitment to practice abstinence, usually teetotalism or chastity

* The Pledge (New Hampshire), a promise about taxes by New Hampshire politicians

* Pledge of Allegianc ...

of a person or a member of that person's family, to serve another person providing credit. Pawnship was related to, yet distinct from, slavery in most conceptualizations, because the arrangement could include limited, specific terms of service to be provided, and because kinship ties would protect the person from being sold into slavery. Pawnship was a common practice throughout West Africa prior to European contact, including among the Akan people

The Akan () people live primarily in present-day Ghana and Ivory Coast in West Africa. The Akan language (also known as ''Twi/Fante'') are a group of dialects within the Central Tano branch of the Potou–Tano subfamily of the Niger–Con ...

, the Ewe people

The Ewe people (; ee, Eʋeawó, lit. "Ewe people"; or ''Mono Kple Volta Tɔ́sisiwo Dome'', lit. "Ewe nation","Eʋenyigba" Eweland;) are a Gbe-speaking ethnic group. The largest population of Ewe people is in Ghana (6.0 million), and the second ...

, the Ga people, the Yoruba people

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitut ...

, and the Edo people

The Edo or Benin people are an Edoid ethnic group primarily found in Edo State, Southern part of Nigeria. They speak the Edo language and are the descendants of the founders of the Benin Empire. They are closely related to other ethnic gr ...

(in modified forms, it also existed among the Efik people, the Igbo people

The Igbo people ( , ; also spelled Ibo" and formerly also ''Iboe'', ''Ebo'', ''Eboe'',

*

*

* ''Eboans'', ''Heebo'';

natively ) are an ethnic group in Nigeria. They are primarily found in Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo States. A s ...

, the Ijaw people, and the Fon people

The Fon people, also called Fon nu, Agadja or Dahomey, are a Gbe ethnic group.Fon people

Encyclopædia Britan ...

).

Encyclopædia Britan ...

Military slavery

Military slavery involved the acquisition and training of conscripted military units which would retain the identity of military slaves even after their service. Slave soldier groups would be run by a ''Patron'', who could be the head of a government or an independent warlord, and who would send his troops out for money and his own political interests.

This was most significant in the Nile valley (primarily in

Military slavery involved the acquisition and training of conscripted military units which would retain the identity of military slaves even after their service. Slave soldier groups would be run by a ''Patron'', who could be the head of a government or an independent warlord, and who would send his troops out for money and his own political interests.

This was most significant in the Nile valley (primarily in Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

and Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The ...

), with slave military units organized by various Islamic authorities, and with the war chiefs of Western Africa. The military units in Sudan were formed in the 1800s through large-scale military raiding in the area which is currently the countries of Sudan and South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of th ...

.

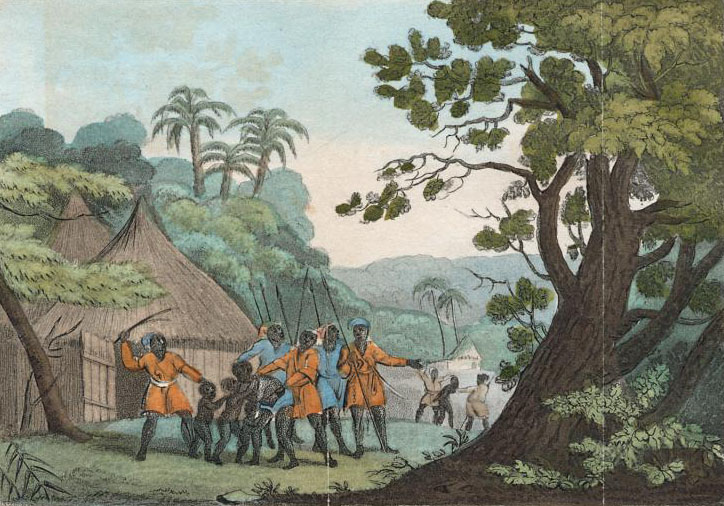

Slaves for sacrifice

Human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherei ...

was common in West African states up to and during the 19th century. Although archaeological evidence is not clear on the issue prior to European contact, in those societies that practiced human sacrifice, slaves became the most prominent victims.

The Annual customs of Dahomey were the most notorious example of human sacrifice of slaves, where 500 prisoners would be sacrificed. Sacrifices were carried out all along the West African coast and further inland. Sacrifices were common in the Benin Empire

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as the Edo Kingdom, or the Benin Empire ( Bini: ') was a kingdom within what is now southern Nigeria. It has no historical relation to the modern republic of Benin, which was known as Dahomey from the 17th c ...

, in what is now Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

, and in the small independent states in what is now southern Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

. In the Ashanti Region

The Ashanti Region is located in southern part of Ghana and it is the third largest of 16 administrative regions, occupying a total land surface of or 10.2 percent of the total land area of Ghana. In terms of population, however, it is the m ...

, human sacrifice was often combined with capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

.

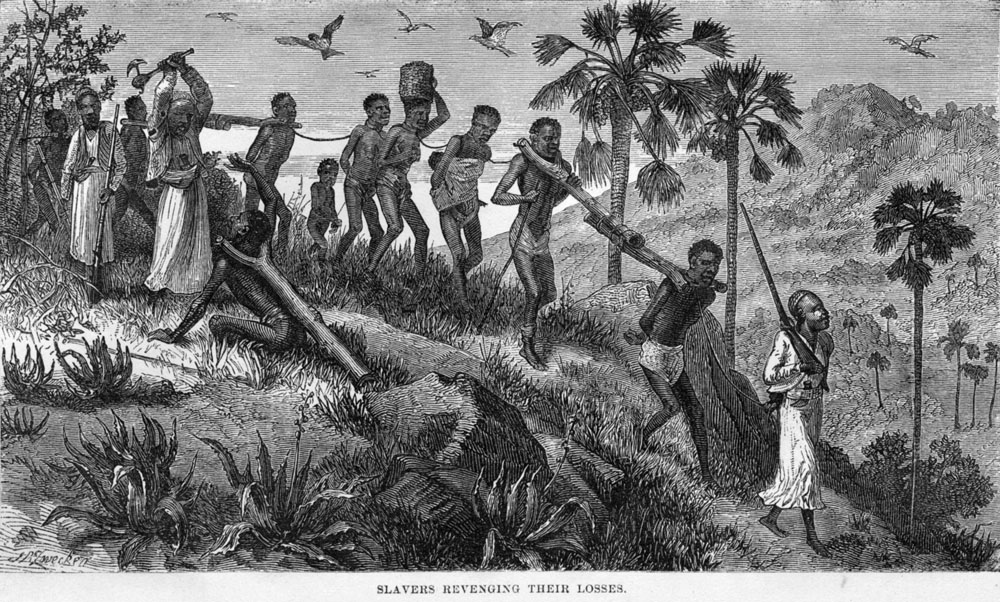

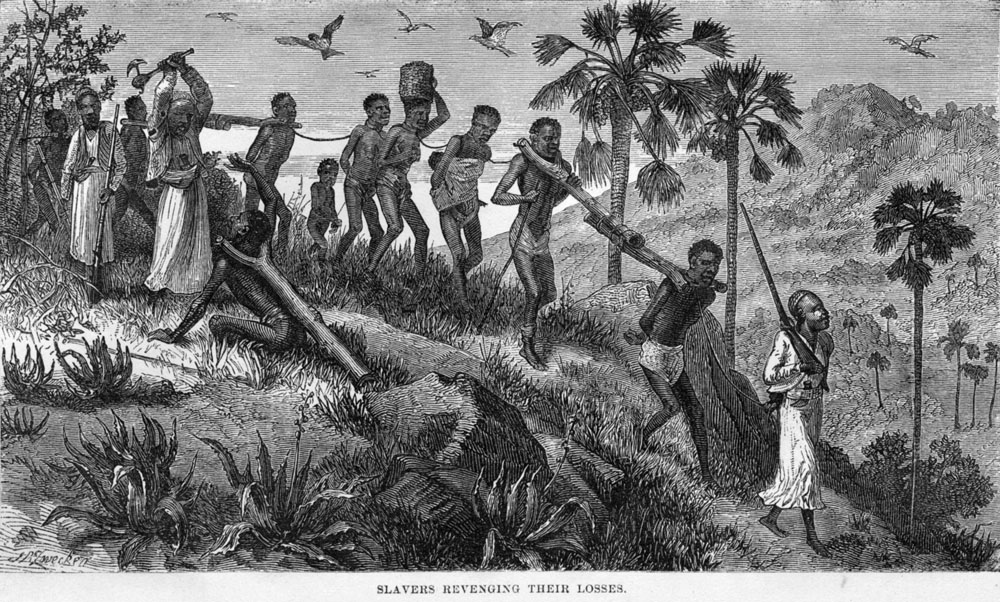

Local slave trade

Many nations such as the Bono State, Ashanti of present-day Ghana and theYoruba

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute ...

of present-day Nigeria were involved in slave-trading. Groups such as the Imbangala of Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

and the Nyamwezi of Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

would serve as intermediaries or roving bands, waging war on African states to capture people for export as slaves. Historians John Thornton and Linda Heywood

Linda Marinda Heywood (born 1945) is an American historian and professor of African American studies and history at Boston University.

Heywood has a BA from Brooklyn College and a PhD from Columbia University. In 2008, she shared the Herskovit ...

of Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. The university is nonsectarian, but has a historical affiliation with the United Methodist Church. It was founded in 1839 by Methodists with its original cam ...

have estimated that of the Africans captured and then sold as slaves to the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

in the Atlantic slave trade, around 90% were enslaved by fellow Africans who sold them to European traders. Henry Louis Gates, the Harvard Chair of African and African American Studies, has stated that "without complex business partnerships between African elites and European traders and commercial agents, the slave trade to the New World would have been impossible, at least on the scale it occurred."

The entire Bubi ethnic group descends from escaped intertribal slaves owned by various ancient West-central African ethnic groups.

Slavery practices throughout Africa

Like most other regions of the world, slavery and forced labour existed in many kingdoms and societies of Africa for hundreds of years. According to Ugo Kwokeji, early European reports of slavery throughout Africa in the 1600s are unreliable because they often conflated various forms of servitude as equal to chattel slavery.

The best evidence of slave practices in Africa come from the major kingdoms, particularly along the coast, and there is little evidence of widespread slavery practices in stateless societies. Slave trading was mostly secondary to other trade relationships; however, there is evidence of a trans- Saharan slave trade route from Roman times which persisted in the area after the fall of the

Like most other regions of the world, slavery and forced labour existed in many kingdoms and societies of Africa for hundreds of years. According to Ugo Kwokeji, early European reports of slavery throughout Africa in the 1600s are unreliable because they often conflated various forms of servitude as equal to chattel slavery.

The best evidence of slave practices in Africa come from the major kingdoms, particularly along the coast, and there is little evidence of widespread slavery practices in stateless societies. Slave trading was mostly secondary to other trade relationships; however, there is evidence of a trans- Saharan slave trade route from Roman times which persisted in the area after the fall of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. However, kinship structures and rights provided to slaves (except those captured in war) appears to have limited the scope of slave trading before the start of the trans-Saharan slave trade, Indian Ocean slave trade and the Atlantic slave trade.

North Africa

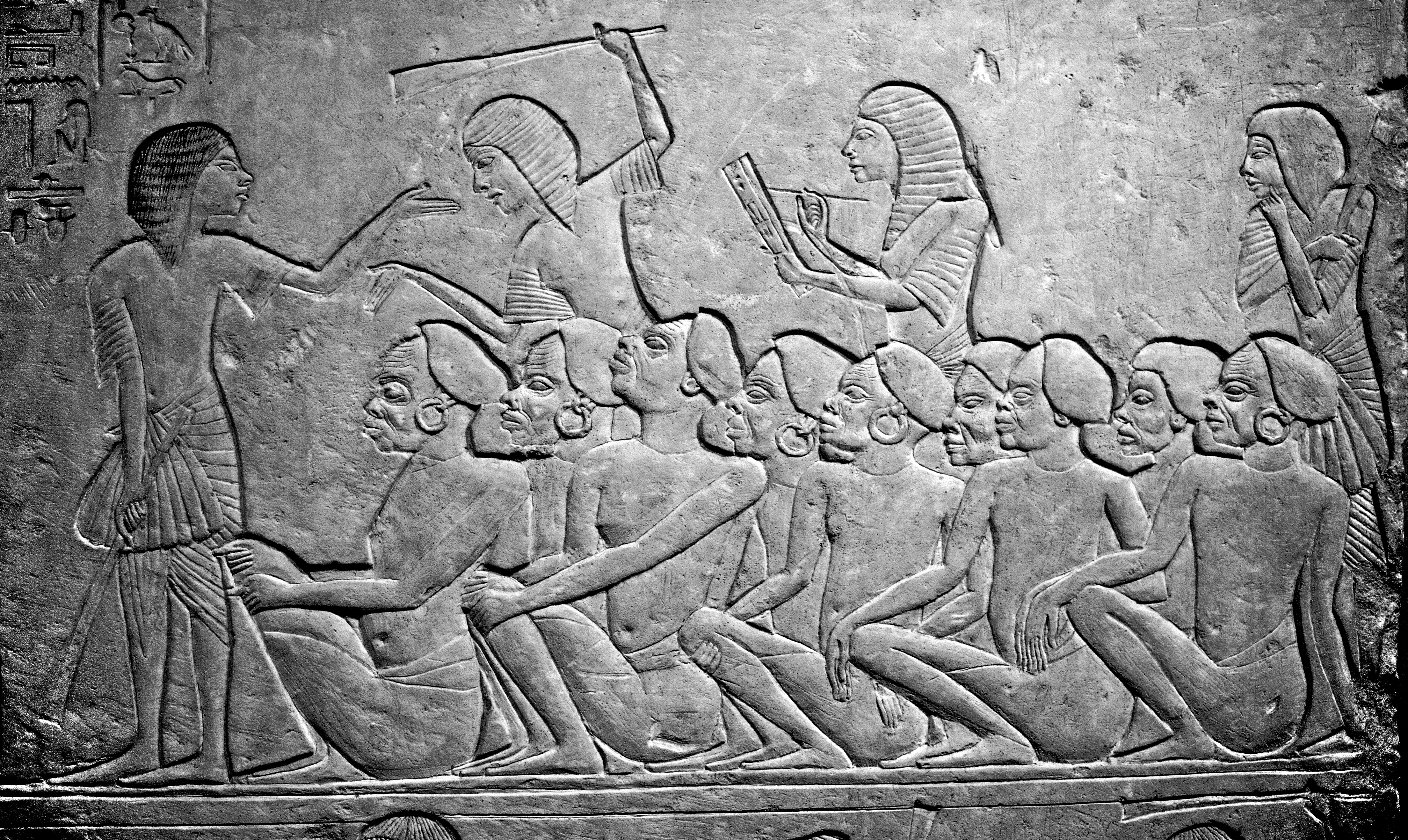

Slavery in northern Africa dates back to ancient Egypt. The

Slavery in northern Africa dates back to ancient Egypt. The New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

(1558–1080 BC) brought in large numbers of slaves as prisoners of war up the Nile valley

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

and used them for domestic and supervised labour. Ptolemaic Egypt (305 BC–30 BC) used both land and sea routes to bring slaves in.

Chattel slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to per ...

had been legal and widespread throughout North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

when the region was controlled by the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

(145 BC – ca. 430 AD), and by the Eastern Romans from 533 to 695). A slave trade bringing Saharans through the desert to North Africa, which existed in Roman times, continued and documentary evidence in the Nile Valley

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

shows it to have been regulated there by treaty. As the Roman republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

expanded, it enslaved defeated enemies and Roman conquests in Africa were no exception. For example, Orosius records that Rome enslaved 27,000 people from North Africa in 256 BC. Piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

became an important source of slaves for the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

and in the 5th century AD pirates would raid coastal North African villages and enslave the captured. Chattel slavery persisted after the fall of the Roman Empire in the largely Christian communities of the region. After the Islamic expansion into most of the region because of the trade expansion across the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, the practices continued and eventually, the assimilative form of slavery spread to major societies on the southern end of the Sahara (such as Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Ma ...

, Songhai, and Ghana). The medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

slave trade in Europe was mainly to the East and South: the Christian Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and the Muslim World

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

were the destinations, Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

an important source of slaves. Slavery in medieval Europe was so widespread that the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

repeatedly prohibited it—or at least the export of Christian slaves to non-Christian lands was prohibited at, for example, the Council of Koblenz in 922, the Council of London in 1102, and the Council of Armagh in 1171. The slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

was carried out in parts of Europe by Iberian Jews (known as Radhanites

The Radhanites or Radanites (; ar, الرذنية, ''ar-Raðaniyya'') were early medieval Jewish merchants, active in the trade between Christendom and the Muslim world during roughly the 8th to 10th centuries.

Many trade routes previously esta ...

) who were able to transfer slaves from pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...

Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

through Christian Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

to Muslim countries in Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

and Africa.

The

The Mamluks

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

were slave soldiers who converted to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

and served the Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

s and the Ayyubid

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin ...

Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

s during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. The first Mamluks served the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

caliphs in 9th century Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

. Over time, they became a powerful military caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultur ...

, and on more than one occasion they seized power for themselves, for example, ruling Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

from 1250 to 1517. From 1250 Egypt had been ruled by the Bahri dynasty

The Bahri dynasty or Bahriyya Mamluks ( ar, المماليك البحرية, translit=al-Mamalik al-Baḥariyya) was a Mamluk dynasty of mostly Turkic origin that ruled the Egyptian Mamluk Sultanate from 1250 to 1382. They followed the Ayyubid ...

of Kipchak Turk origin. White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

enslaved people from the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

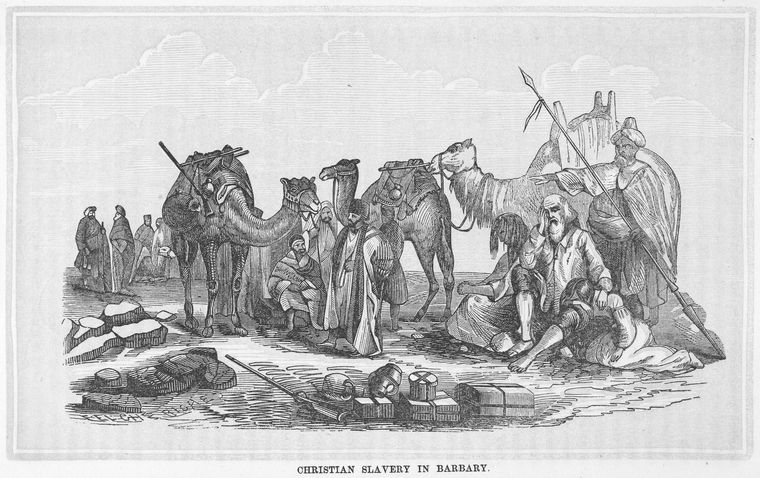

served in the army and formed an elite corps of troops, eventually revolting in Egypt to form the Burgi dynasty. According to Robert Davis between 1 million and 1.25 million Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe ...

and sold as slaves to North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

between the 16th and 19th centuries. However, to extrapolate his numbers, Davis assumes the number of European slaves captured by Barbary pirates were constant for a 250-year period, stating:

Davis' numbers have been disputed by other historians, such as David Earle, who cautions that the true picture of European slaves is clouded by the fact the corsairs also seized non-Christian whites from eastern Europe and black people from West Africa.

In addition, the number of slaves traded was hyperactive, with exaggerated estimates relying on peak years to calculate averages for entire centuries, or millennia. Hence, there were wide fluctuations year-to-year, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries, given slave imports, and also given the fact that, prior to the 1840s, there are no consistent records. Middle East expert John Wright cautions that modern estimates are based on back-calculations from human observation.

Such observations, across the late 1500s and early 1600s observers, estimate that around 35,000 European Christian slaves held throughout this period on the Barbary Coast, across Tripoli, Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, but mostly in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

. The majority were sailors (particularly those who were English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

), taken with their ships, but others were fishermen and coastal villagers. However, most of these captives were people from lands close to Africa, particularly Spain and Italy.

The coastal villages and towns of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, and Mediterranean islands

The following is a list of islands in the Mediterranean Sea. The two main island countries in the region are Malta and Cyprus, while other countries with islands in the Mediterranean Sea include Italy, France, Greece, Spain, Tunisia, Croatia, ...

were frequently attacked by the pirates, and long stretches of the Italian and Spanish coasts were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants; after 1600 Barbary pirates occasionally entered the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and struck as far north as Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

. The most famous corsairs were the Ottoman Barbarossa

Barbarossa, a name meaning "red beard" in Italian, primarily refers to:

* Frederick Barbarossa (1122–1190), Holy Roman Emperor

* Hayreddin Barbarossa (c. 1478–1546), Ottoman admiral

* Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Uni ...

("Redbeard"), and his older brother Oruç, Turgut Reis

Dragut ( tr, Turgut Reis) (1485 – 23 June 1565), known as "The Drawn Sword of Islam", was a Muslim Ottoman naval commander, governor, and noble, of Turkish or Greek descent. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extend ...

(known as Dragut in the West), Kurtoğlu (known as Curtogoli in the West), Kemal Reis, Salih Reis, and Koca Murat Reis.

In 1544, Hayreddin Barbarossa captured Ischia

Ischia ( , , ) is a volcanic island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It lies at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, about from Naples. It is the largest of the Phlegrean Islands. Roughly trapezoidal in shape, it measures approximately east to ...

, taking 4,000 prisoners in the process, and deported to slavery some 9,000 inhabitants of Lipari

Lipari (; scn, Lìpari) is the largest of the Aeolian Islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the northern coast of Sicily, southern Italy; it is also the name of the island's main town and ''comune'', which is administratively part of the Metropol ...

, almost the entire population. In 1551, Dragut enslaved the entire population of the Maltese island Gozo

Gozo (, ), Maltese: ''Għawdex'' () and in antiquity known as Gaulos ( xpu, 𐤂𐤅𐤋, ; grc, Γαῦλος, Gaúlos), is an island in the Maltese archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea. The island is part of the Republic of Malta. After ...

, between 5,000 and 6,000, sending them to Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

. When pirates sacked Vieste in southern Italy in 1554 they took an estimated 7,000 slaves. In 1555, Turgut Reis sailed to Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

and ransacked Bastia, taking 6,000 prisoners. In 1558 Barbary corsairs captured the town of Ciutadella, destroyed it, slaughtered the inhabitants, and carried off 3,000 survivors to Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

as slaves. In 1563 Turgut Reis landed at the shores of the province of Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

, Spain, and captured the coastal settlements in the area like Almuñécar

Almuñécar () is a Spanish city and municipality located in the southwestern part of the comarca of the Costa Granadina, in the province of Granada. It is located on the shores of the Mediterranean sea and borders the Granadin municipalities ...

, along with 4,000 prisoners. Barbary pirates frequently attacked the Balearic islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

, resulting in many coastal watchtowers and fortified churches being erected. The threat was so severe that Formentera became uninhabited.

Early modern sources are full of descriptions of the sufferings of Christian galley slaves of the

Early modern sources are full of descriptions of the sufferings of Christian galley slaves of the Barbary corsairs

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe a ...

:

As late as 1798, the islet near Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

was attacked by the Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

ns and over 900 inhabitants were taken away as slaves.

Sahrawi-Moorish

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or s ...

society in Northwest Africa was traditionally (and still is, to some extent) stratified into several tribal castes, with the Hassane

The Hassane is a name for the traditionally dominant warrior tribes of the Sahrawi-Moorish areas of present-day Mauritania, southern Morocco and Western Sahara. Although lines were blurred by intermarriage and tribal re-affiliation, the Hassane we ...

warrior tribes ruling and extracting tribute – horma

The horma was a tribute paid by subservient tribes to their protectors in traditional Sahrawi-Moorish society in today's Mauritania and Western Sahara in North Africa. The powerful Hassane warrior tribes would extract it from low- caste Znaga ...

– from the subservient Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–19 ...

-descended znaga tribes. Below them ranked servile groups known as Haratin, a black population.

Enslaved Sub-Saharan Africans were also transported across North Africa into Arabia to do agricultural work because of their resistance to malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

that plagued the Arabia and North Africa at the time of early enslavement. Sub-Saharan Africans were able to endure the malaria-infested lands they were transported to, which is why North Africans were not transported despite their close proximity to Arabia and its surrounding lands.

Horn of Africa

In the

In the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004 ...

, the Christian kings of the Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

often exported pagan Nilotic slaves from their western borderlands, or from newly conquered or reconquered lowland territories.Pankhurst. ''Ethiopian Borderlands'', p. 432. The Somali

Somali may refer to:

Horn of Africa

* Somalis, an inhabitant or ethnicity associated with Greater Somali Region

** Proto-Somali, the ancestors of modern Somalis

** Somali culture

** Somali cuisine

** Somali language, a Cushitic language

** Somali ...

and Afar Muslim sultanates, such as the medieval Adal Sultanate, through their ports also traded Zanj

Zanj ( ar, زَنْج, adj. , ''Zanjī''; fa, زنگی, Zangi) was a name used by medieval Muslim geographers to refer to both a certain portion of Southeast Africa (primarily the Swahili Coast) and to its Bantu inhabitants. This word is als ...

(Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Nationa ...

) slaves who were captured from the hinterland.

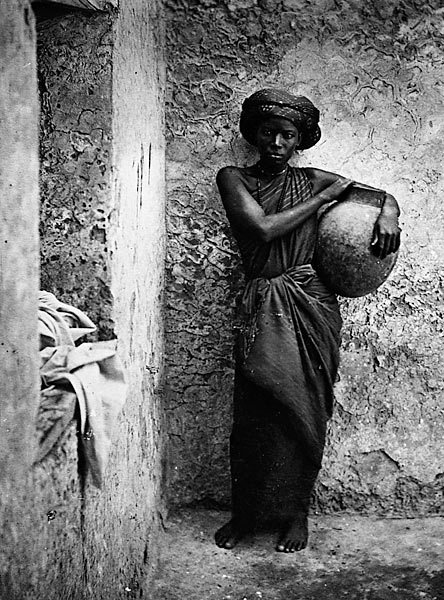

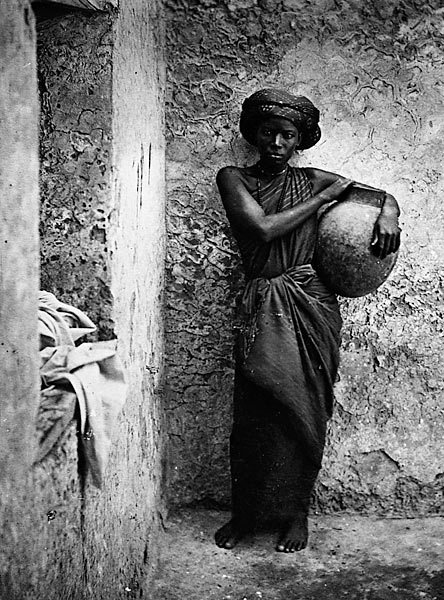

Slavery, as practiced in

Slavery, as practiced in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, was essentially domestic and was geared more towards women; this was the trend for most of Africa as well. Women were transported across the Sahara, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

trade more than men. Enslaved people served in the houses of their masters or mistresses, and were not employed to any significant extent for productive purpose. The enslaved were regarded as second-class members of their owners' family. The first attempt to abolish slavery in Ethiopia was made by Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855–68), although the slave trade was not abolished legally until 1923 with Ethiopia's ascension to the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

. Anti-Slavery Society estimated there were 2 million slaves in the early 1930s, out of an estimated population of between 8 and 16 million. Slavery continued in Ethiopia until the Italian invasion in October 1935, when the institution was abolished by order of the Italian occupying forces. In response to pressure by Western Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the Declaration by United Nations, United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during the World War II, Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis ...

, Ethiopia officially abolished slavery and involuntary servitude after having regained its independence in 1942. On 26 August 1942, Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

issued a proclamation outlawing slavery.

In Somali territories, slaves were purchased in the slave market exclusively to do work on plantation grounds. In terms of legal considerations, the customs regarding the treatment of Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Nationa ...

slaves were established by the decree of Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

s and local administrative delegates. Additionally, freedom for these plantation slaves was also often acquired through eventual emancipation, escape, and ransom.Catherine Lowe Besteman, ''Unraveling Somalia: Race, Class, and the Legacy of Slavery'' (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1999), pp. 83–84.

Central Africa

Slaves were transported since antiquity along trade routes crossing the Sahara.

Oral tradition recounts slavery existing in the

Slaves were transported since antiquity along trade routes crossing the Sahara.

Oral tradition recounts slavery existing in the Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo ( kg, Kongo dya Ntotila or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' pt, Reino do Congo) was a kingdom located in central Africa in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the ...

from the time of its formation with Lukeni lua Nimi enslaving the Mwene Kabunga whom he conquered to establish the kingdom. Early Portuguese writings show that the Kingdom did have slavery before contact, but that they were primarily war captives from the Kingdom of Ndongo.

Slavery was common along the Upper Congo River

The Congo River ( kg, Nzâdi Kôngo, french: Fleuve Congo, pt, Rio Congo), formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the second largest river in the world by discharg ...

, and in the second half of the 18th century the region became a major source of slaves for the Atlantic Slave Trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

, when high slave prices on the coast made long-distance slave trading profitable. When the Atlantic trade came to an end, the prices of slaves dropped dramatically, and the regional slave trade grew, dominated by Bobangi traders. The Bobangi also purchased a large number of slaves with profits from selling ivory, who they used to populate their villages. A distinction was made between two different types of slaves in this region; slaves who had been sold by their kin group, typically as a result of undesirable behavior such as adultery, were unlikely to attempt to flee. In addition to those considered socially undesirable, the sale of children was also common in times of famine. Slaves who were captured, however, were likely to attempt to escape and had to be moved hundreds of kilometers from their homes as a safeguard against this.

The slave trade had a profound impact on this region of Central Africa, completely reshaping various aspects of society. For instance, the slave trade helped to create a robust regional trade network for the foodstuffs and crafted goods of small producers along the river. As the transport of only a few slaves in a canoe was sufficient to cover the cost of a trip and still make a profit, traders could fill any unused space on their canoes with other goods and transport them long distances without a significant markup on price. While the large profits from the Congo River slave trade only went to a small number of traders, this aspect of the trade provided some benefit to local producers and consumers.

West Africa

Various forms of slavery were practiced in diverse ways in different communities of West Africa prior to European trade. According to Ghanaian historian Akosua Perbi, indigenous slavery in locations like Ghana had been established by the 1st century AD, with origins sometime in the ancient period. Even though slavery did exist, it was not nearly as prevalent within most West African societies that were not Islamic before the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. The prerequisites for slave societies to exist weren't present in West Africa prior to the Atlantic slave trade considering the small market sizes and the lack of adivision of labour

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (specialisation). Individuals, organizations, and nations are endowed with, or acquire specialised capabilities, an ...

. Most West African societies were formed in Kinship units which would make slavery a rather marginal part of the production process within them. Slaves within Kinship-based societies would have had almost the same roles that free members had. Martin Klein has said that before the Atlantic trade, slaves in Western Sudan "made up a small part of the population, lived within the household, worked alongside free members of the household, and participated in a network of face-to-face links." With the development of the trans-Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

n slave trade and the economies of gold in the western Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid cli ...

, a number of the major states became organized around the slave trade, including the Ghana Empire

The Ghana Empire, also known as Wagadou ( ar, غانا) or Awkar, was a West African empire based in the modern-day southeast of Mauritania and western Mali that existed from c. 300 until 1100. The Empire was founded by the Soninke people, a ...

, the Mali Empire

The Mali Empire (Manding: ''Mandé''Ki-Zerbo, Joseph: ''UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century'', p. 57. University of California Press, 1997. or Manden; ar, مالي, Māl� ...

, the Bono State and Songhai Empire. However, other communities in West Africa largely resisted the slave trade. The Jola refused to participate in the slave trade up into the end of the seventeenth century, and did not use slave labour within their own communities until the nineteenth century. The Kru

KRU was a Malaysian pop boy band formed in 1992. The group comprises three brothers, namely Datuk Norman Abdul Halim, Datuk Yusry Abdul Halim and Edry Abdul Halim'. Apart from revolutionising the Malaysian music scene with their blend of pop, ...

and Baga also fought against the slave trade. The Mossi Kingdoms tried to take over key sites in the trans-Saharan trade and, when these efforts failed, the Mossi became defenders against slave raiding by the powerful states of the western Sahel. The Mossi would eventually enter the slave trade in the 1800s with the Atlantic slave trade being the main market.

Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

was a catalyst for slave trade, and from the Homann Heirs map figure shown, shows a starting point for migration and a firm port of trade. The culture of the Gold Coast was based largely on the power that individuals held, rather than the land cultivated by a family. Western Africa, and specifically places like Senegal, were able to arrive at the development of slavery through analyzing the aristocratic advantages of slavery and what would best suit the region. This sort of governing that used "political tool" of discerning the different labours and methods of assimilative slavery. The domestic and agricultural labour became more evidently primary in Western Africa due to slaves being regarded as these "political tools" of access and status. Slaves often had more wives than their owners, and this boosted the class of their owners. Slaves were not all used for the same purpose. European colonizing countries were participating in the trade to suit the economic needs of their countries. The parallel of "Moorish" traders found in the desert compared to the Portuguese traders that were not as established pointed out the differences in uses of slaves at this point, and where they were headed in the trade.

Historian Walter Rodney identified no slavery or significant domestic servitude in early European accounts on the Upper Guinea Upper Guinea is a geographical term used in several contexts:

# Upper Guinea (french: Haute-Guinée) is one of the four geographic regions of the Republic of Guinea, being east of Futa Jalon, north of Forest Guinea, and bordering Mali. The popula ...

region and I. A. Akinjogbin contends that European accounts reveal that the slave trade was not a major activity along the coast controlled by the Yoruba people

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitut ...

and Aja people before Europeans arrived. In a paper read to the Ethnological Society of London in 1866, the viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

of Lokoja Mr T. Valentine Robins, who in 1864 accompanied an expedition up the River Niger aboard , described slavery in the region:

With the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade, demand for slaves in West Africa increased and a number of states became centered on the slave trade and domestic slavery increased dramatically. Hugh Clapperton in 1824 believed that half the population of Kano were enslaved people. Near the Gold Coast, many of those enslaved came from deep inside the interior of the continent as defeated people from numerous wars and were sold off quickly as part of a practice called "eating the country" that aimed to disperse fallen enemies to prevent regrouping. According to Ghanaian historian Akosua Perbi, from the 15th to 19th centuries in Ghana, major sources of slaves came from warfare, slave markets, pawning, raids, kidnapping and tributes while minor sources were from gifts, convicts, communal or private deals.

In the Senegambia

The Senegambia (other names: Senegambia region or Senegambian zone,Barry, Boubacar, ''Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade'', (Editors: David Anderson, Carolyn Brown; trans. Ayi Kwei Armah; contributors: David Anderson, American Council of Le ...

region, between 1300 and 1900, close to one-third of the population was enslaved. In early Islamic

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ma ...

states of the western Sahel, including Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

(750–1076), Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Ma ...

(1235–1645), Segou (1712–1861), and Songhai (1275–1591), about a third of the population were enslaved. In Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

in the 19th century about half of the population consisted of enslaved people. Among the Vai people, Vai people, during the 19th century, three quarters of people were slaves. In the 19th century at least half the population was enslaved among the Duala of the Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the ...

and other peoples of the lower Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesKongo, and the Kasanje kingdom and

With sea trade from the eastern African Great Lakes region to

With sea trade from the eastern African Great Lakes region to

Slave relationships in Africa have been transformed through four large-scale processes: the trans-Saharan slave trade, the Indian Ocean slave trade, the Atlantic slave trade, and the slave emancipation policies and movements in the 19th and 20th centuries. Each of these processes significantly changed the forms, level, and economics of slavery in Africa.

Slave practices in Africa were used during different periods to justify specific forms of European engagement with the peoples of Africa. Eighteenth century writers in Europe claimed that slavery in Africa was quite brutal in order to justify the Atlantic slave trade. Later writers used similar arguments to justify intervention and eventual colonization by European powers to end slavery in Africa.

Africans knew of the harsh slavery that awaited slaves in the New World. Many elite Africans visited Europe on slave ships following the prevailing winds through the New World. One example of this occurred when Antonio Manuel, Kongo’s ambassador to the Vatican, went to Europe in 1604, stopping first in

Slave relationships in Africa have been transformed through four large-scale processes: the trans-Saharan slave trade, the Indian Ocean slave trade, the Atlantic slave trade, and the slave emancipation policies and movements in the 19th and 20th centuries. Each of these processes significantly changed the forms, level, and economics of slavery in Africa.

Slave practices in Africa were used during different periods to justify specific forms of European engagement with the peoples of Africa. Eighteenth century writers in Europe claimed that slavery in Africa was quite brutal in order to justify the Atlantic slave trade. Later writers used similar arguments to justify intervention and eventual colonization by European powers to end slavery in Africa.

Africans knew of the harsh slavery that awaited slaves in the New World. Many elite Africans visited Europe on slave ships following the prevailing winds through the New World. One example of this occurred when Antonio Manuel, Kongo’s ambassador to the Vatican, went to Europe in 1604, stopping first in

Early records of

Early records of

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade took place across the

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade took place across the  It has been argued that a decrease in able-bodied people as a result of the Atlantic slave trade limited many societies ability to cultivate land and develop. Many scholars argue that the transatlantic slave trade, left Africa underdeveloped, demographically unbalanced, and vulnerable to future European colonization.

The first Europeans to arrive on the coast of

It has been argued that a decrease in able-bodied people as a result of the Atlantic slave trade limited many societies ability to cultivate land and develop. Many scholars argue that the transatlantic slave trade, left Africa underdeveloped, demographically unbalanced, and vulnerable to future European colonization.

The first Europeans to arrive on the coast of  The Spanish were the first Europeans to use enslaved Africans in America on islands such as

The Spanish were the first Europeans to use enslaved Africans in America on islands such as

According to Patrick Manning, internal slavery was most important to Africa in the second half of the 19th century, stating "if there is any time when one can speak of African societies being organized around a slave mode production, 850–1900was it". The abolition of the Atlantic slave trade resulted in the economies of African states dependent on the trade being reorganized towards domestic plantation slavery and legitimate commerce worked by slave labour. Slavery before this period was generally domestic.

The continuing anti-slavery movement in Europe became an excuse and a

According to Patrick Manning, internal slavery was most important to Africa in the second half of the 19th century, stating "if there is any time when one can speak of African societies being organized around a slave mode production, 850–1900was it". The abolition of the Atlantic slave trade resulted in the economies of African states dependent on the trade being reorganized towards domestic plantation slavery and legitimate commerce worked by slave labour. Slavery before this period was generally domestic.

The continuing anti-slavery movement in Europe became an excuse and a

Chokwe Chokwe may refer to:

*Chokwe people, a Central African ethnic group

** Chokwe language, a Bantu language

* Chokwe or Tshokwe, Botswana, a village

* Chokwe, Malawi

* Chókwè District, Mozambique

**Chokwe, Mozambique

Chokwé, and earlier known a ...

of Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

. Among the Ashanti and Yoruba

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute ...

a third of the population consisted of enslaved people. The population of the Kanem (1600–1800) was about one-third enslaved. It was perhaps 40% in Bornu (1580–1890). Between 1750 and 1900 from one- to two-thirds of the entire population of the Fulani jihad states consisted of enslaved people. The population of the largest Fulani state, Sokoto, was at least half-enslaved in the 19th century. Among the Adrar 15 percent of people were enslaved, and 75 percent of the Gurma

Gurma (also called Gourma or Gourmantché) is an ethnic group living mainly in northeastern Ghana, Burkina Faso, around Fada N'Gourma, and also in northern areas of Togo and Benin, as well as southwestern Niger. They number approximately 1,750 ...

were enslaved. Slavery was extremely common among the Tuareg people

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym: ''Imuhaɣ/Imušaɣ/Imašeɣăn/Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group that principally inhabit the Sahara in a vast area stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern Al ...

s and many still hold slaves today.

When British rule was first imposed on the Sokoto Caliphate

The Sokoto Caliphate (), also known as the Fulani Empire or the Sultanate of Sokoto, was a Sunni Muslim caliphate in West Africa. It was founded by Usman dan Fodio in 1804 during the Fulani jihads after defeating the Hausa Kingdoms in the F ...

and the surrounding areas in northern Nigeria at the turn of the 20th century, approximately 2 million to 2.5 million people there were enslaved. Slavery in northern Nigeria was finally outlawed in 1936.

African Great Lakes

With sea trade from the eastern African Great Lakes region to

With sea trade from the eastern African Great Lakes region to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, China, and India during the first millennium AD, slaves are mentioned as a commodity of secondary importance to gold and ivory. When mentioned, the slave trade appears to be of a small-scale and mostly involves slave raiding of women and children along the islands of Kilwa Kisiwani

Kilwa Kisiwani (English: ''Kilwa Island'') is an island, national historic site, and hamlet community located in the township of Kilwa Masoko, the district seat of Kilwa District in the Tanzanian region of Lindi Region in southern Tanzania. Ki ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

, and Pemba. In places such as Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The ...

, the experience for women in slavery was different than that of customary slavery practices at the time. The roles assumed were based on gender and position within the society First one must make the distinction in Ugandan slavery of peasants and slaves. Researchers Shane Doyle and Henri Médard assert the distinction with the following:

"Peasants were rewarded for valour in battle by the present of slaves by the lord or chief for whom they had fought. They could be given slaves by relatives who had been promoted to the rank of chiefs, and they could inherit slaves from their fathers. There were the abanyage (those pillaged or stolen in war) as well as the abagule (those bought). All these came under the category of abenvumu or true slaves, that is to say people not free in any sense. In a superior position were the young Ganda given by their maternal uncles into slavery (or pawnship), usually in lieu of debts... Besides such slaves both chiefs and king were served by sons of well to do men who wanted to please them and attract favour for themselves or their children. These were the abasige and formed a big addition to a noble household.... All these different classes of dependents in a household were classed as Medard & Doyle abaddu (male servants) or abazana (female servants) whether they were slave or free-born.(175)"

In the Great Lakes region of Africa (around present-day Uganda), linguistic evidence shows the existence of slavery through war capture, trade, and pawning going back hundreds of years; however, these forms, particularly pawning, appear to have increased significantly in the 18th and 19th centuries. These slaves were considered to be more trustworthy than those from the Gold Coast. They were regarded with more prestige because of the training they responded to.

The language for slaves in the Great Lakes region varied. This region of water made it easy for capture of slaves and transport. Captive, refugee, slave, peasant were all used in order to describe those in the trade. The distinction was made by where and for what purpose they would be utilized for. Methods like pillage, plunder

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

, and capture were all semantics common in this region to depict the trade.

Historians Campbell and Alpers argue that there were a host of different categories of labour in Southeast Africa and that the distinction between slave and free individuals was not particularly relevant in most societies. However, with increasing international trade in the 18th and 19th century, Southeast Africa began to be involved significantly in the Atlantic slave trade; for example, with the king of Kilwa island signing a treaty with a French merchant in 1776 for the delivery of 1,000 slaves per year.

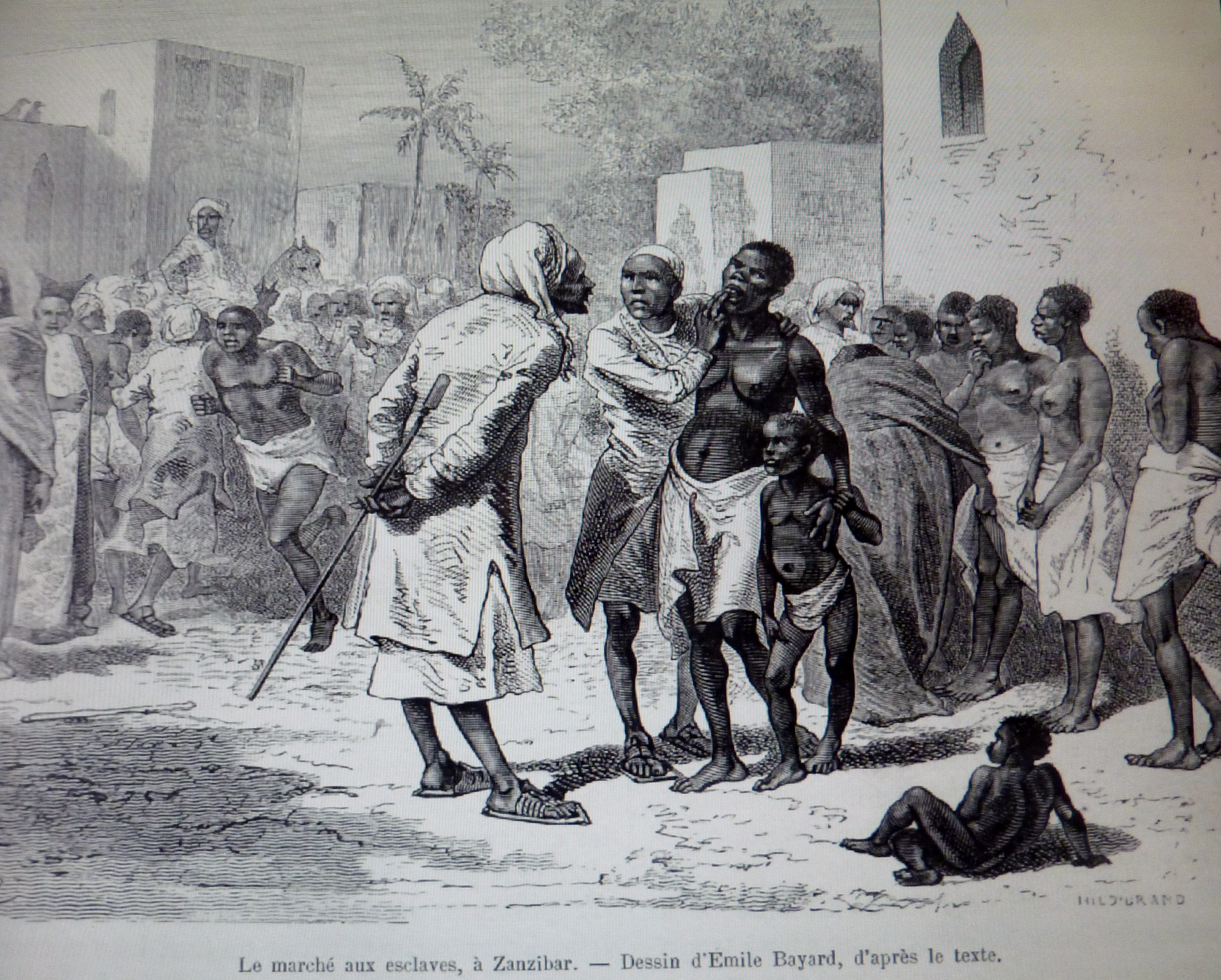

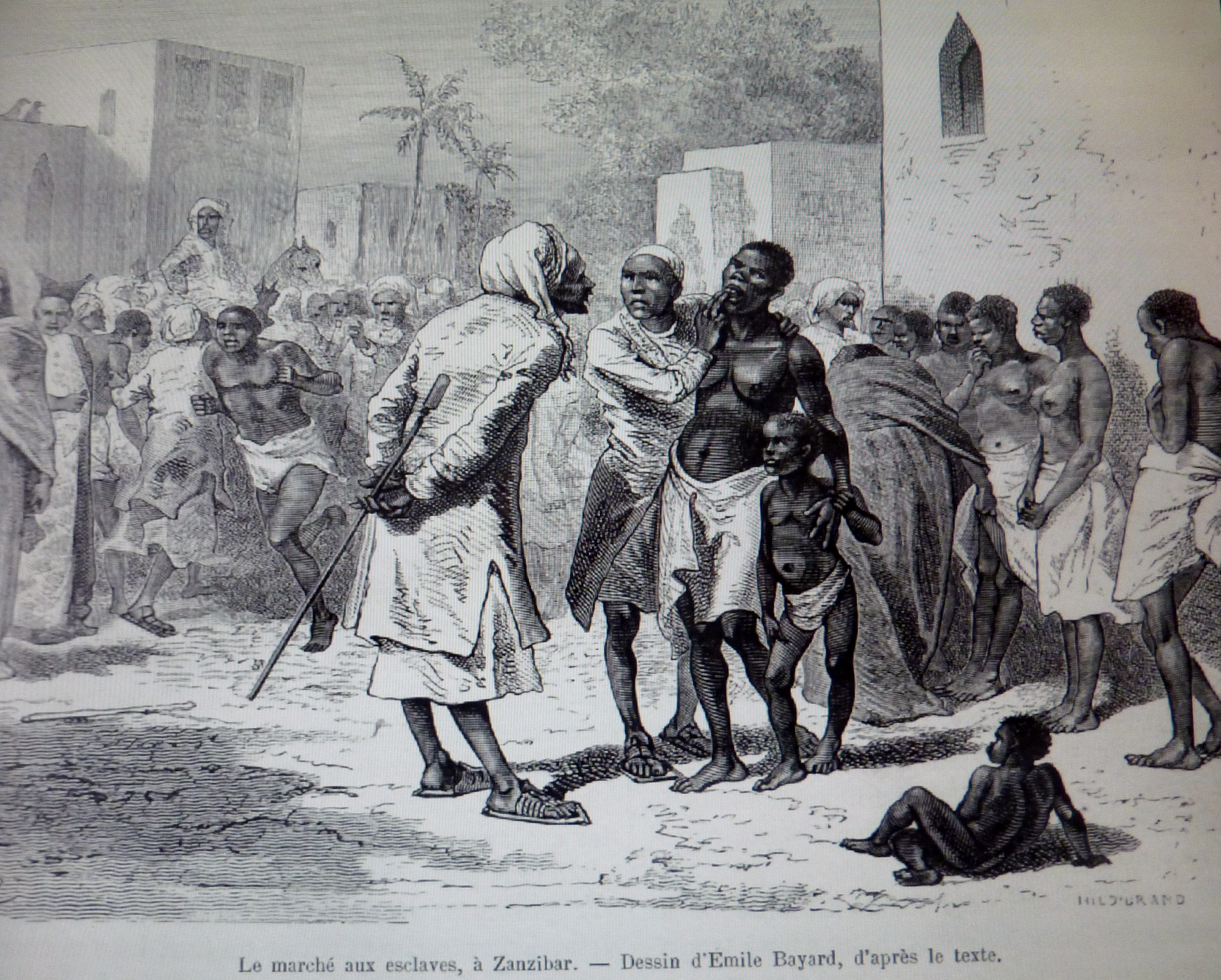

At about the same time, merchants from Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, and Southeast Africa began establishing plantations along the coasts and on the islands, To provide workers on these plantations, slave raiding and slave holding became increasingly important in the region and slave traders (most notably Tippu Tip) became prominent in the political environment of the region. The Southeast African trade reached its height in the early decades of the 1800s with up to 30,000 slaves sold per year. However, slavery never became a significant part of the domestic economies except in Sultanate of Zanzibar where plantations and agricultural slavery were maintained. Author and historian Timothy Insoll

Timothy Insoll (born 1967) is a British archaeologist and Africanist and Islamic Studies scholar. Since 2016 he has been Al-Qasimi Professor of African and Islamic Archaeology at the University of Exeter. He is also founder and director of the C ...

wrote: "Figures record the exporting of 718,000 slaves from the Swahili coast during the 19th century, and the retention of 769,000 on the coast." At various times, between 65 and 90 percent of Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

was enslaved. Along the Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

coast, 90 percent of the population was enslaved, while half of Madagascar