Siege of Naxos (499 BC) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The siege of Naxos (499 BC) was a failed attempt by the Milesian tyrant Aristagoras, operating with support from, and in the name of the

I, 142–151

/ref> The Ionians had settled about the coasts of

I, 142

/ref> The cities of Ionia had remained independent until they were conquered by the famous Lydian king

I, 26

/ref> The Ionian cities then remained under Lydian rule until Lydia was in turn conquered by the nascent

I, 141

/ref> The Persians found the Ionians difficult to rule. Elsewhere in the empire, Cyrus was able to identify elite native groups to help him rule his new subjects—such as the priesthood of Judea. No such group existed in Greek cities at this time; while there was usually an aristocracy, this was inevitably divided into feuding factions.Holland, pp. 147–151. The Persians thus settled for the sponsoring a About 40 years after the Persian conquest of Ionia, and in the reign of the fourth Persian king,

About 40 years after the Persian conquest of Ionia, and in the reign of the fourth Persian king,

pp. 269–277.

/ref> The island of

V, 28

/ref> Despite its success, Naxos was not immune to class tensions and internal strife, and shortly before 500 BC, the population seized power, expelling the aristocrats and establishing a democracy.Lloyd, p. 143. In 500 BC, Aristagoras was approached by some of the exiles from

V, 30

/ref> Seeing an opportunity to strengthen his position in Miletus by conquering Naxos, Aristagoras approached the

V, 31

/ref> Furthermore, Aristagoras suggested that once Naxos fell, the other Cyclades would also quickly follow, and he even suggested that

V, 32

/ref>

V, 33

/ref> Herodotus recounts that Megabates made inspections of the ships (probably whilst beached for the night), and came across one ship from Myndus which had not posted any sentries. Megabates ordered his guard to find the captain of the ship, Scylax, and then had the captain thrust into one of the ship's oar holes with his head outside and his body inside the ship. News reached Aristagoras of the treatment of his friend and he went to Megabates and asked him to reconsider his decision. When Megabates refused to grant Aristagoras's wishes, Aristagoras simply cut the captain loose himself. Predictably, Megabates was furious with Aristagoras, who in turn retorted "But you, what have you to do with these matters? Did not Artaphernes send you to obey me and to sail wherever I bid you? Why are you so meddlesome?". According to Herodotus, Megabates was so enraged by this that he sent messengers to the Naxians to warn them of the approach of the Persian force.

Modern historians, doubting that a Persian commander would have sabotaged his own invasion, have suggested several other possible scenarios. It is, however, impossible to know exactly how the Naxians became aware of the invasion, but undoubtedly they were aware, and began to make preparations.Keaveney, p. 76. Herodotus tells us that the Naxians had previously had no inkling of the expedition, but that when news arrived they brought everything in from the fields, gathered enough food with which to survive a siege and reinforced their walls.Herodotu

Herodotus recounts that Megabates made inspections of the ships (probably whilst beached for the night), and came across one ship from Myndus which had not posted any sentries. Megabates ordered his guard to find the captain of the ship, Scylax, and then had the captain thrust into one of the ship's oar holes with his head outside and his body inside the ship. News reached Aristagoras of the treatment of his friend and he went to Megabates and asked him to reconsider his decision. When Megabates refused to grant Aristagoras's wishes, Aristagoras simply cut the captain loose himself. Predictably, Megabates was furious with Aristagoras, who in turn retorted "But you, what have you to do with these matters? Did not Artaphernes send you to obey me and to sail wherever I bid you? Why are you so meddlesome?". According to Herodotus, Megabates was so enraged by this that he sent messengers to the Naxians to warn them of the approach of the Persian force.

Modern historians, doubting that a Persian commander would have sabotaged his own invasion, have suggested several other possible scenarios. It is, however, impossible to know exactly how the Naxians became aware of the invasion, but undoubtedly they were aware, and began to make preparations.Keaveney, p. 76. Herodotus tells us that the Naxians had previously had no inkling of the expedition, but that when news arrived they brought everything in from the fields, gathered enough food with which to survive a siege and reinforced their walls.Herodotu

V, 34

/ref>

VII, 184

/ref> and this was probably also true in the first invasion when the whole invasion force was apparently carried in triremes. Furthermore, the Chian ships at the

When the Ionians and Persians arrived at Naxos, they were faced by a well-fortified and supplied city. Herodotus does not explicitly say, but this was presumably the eponymous capital of Naxos. He provides few details of the military actions that ensued, although there is a suggestion that there was an initial assault on the city, which was repelled. The Ionians and Persians thus settled down to besiege the city. However, after four months, the Persians had run out of money, with Aristagoras also spending a great deal. Thoroughly demoralised, the expedition prepared to return to Asia Minor empty handed. Before leaving, they built a stronghold for the exiled Naxian aristocrats on the island. This was a typical strategy in the Greek world for those exiled by internal strife, giving them a base from which to quickly return, as events permitted.

When the Ionians and Persians arrived at Naxos, they were faced by a well-fortified and supplied city. Herodotus does not explicitly say, but this was presumably the eponymous capital of Naxos. He provides few details of the military actions that ensued, although there is a suggestion that there was an initial assault on the city, which was repelled. The Ionians and Persians thus settled down to besiege the city. However, after four months, the Persians had run out of money, with Aristagoras also spending a great deal. Thoroughly demoralised, the expedition prepared to return to Asia Minor empty handed. Before leaving, they built a stronghold for the exiled Naxian aristocrats on the island. This was a typical strategy in the Greek world for those exiled by internal strife, giving them a base from which to quickly return, as events permitted.

V, 35

/ref> Although Herodotus presents the revolt as a consequence of Aristagoras' personal motives, it is clear that Ionia must have been ripe for rebellion anyway, the primary grievance being the tyrants installed by the Persians. Aristagoras's actions have thus been likened to tossing a flame into a kindling box; they incited rebellion across Ionia (and

V, 100

/ref> This force was then guided by the Ephesians through mountains to

V, 101

/ref> The Persian troops in Asia Minor followed the Greek force, catching them outside Ephesus. It is clear that the demoralised and tired Greeks were no match for the Persians, and were completely routed in the battle which ensued at Ephesus. The Ionians who escaped the battle made for their own cities, while the remaining Athenians and Eretrians managed to return to their ships, and sailed back to Greece.Herodotu

V, 102

/ref> Despite these setbacks, the revolt spread further. The Ionians sent men to the

Despite these setbacks, the revolt spread further. The Ionians sent men to the

V, 103

/ref> Furthermore, seeing the spread of the rebellion, the kingdoms of

V, 104

/ref> For the next three years, the Persian army and navy were fully occupied with fighting the rebellions in Caria and Cyprus, and Ionia seems to have had an uneasy peace during these years.Boardman ''et al''

pp. 481–490.

/ref> At the height of the Persian counter-offensive, Aristagoras, sensing the untenability of his position, decided to abandon his position as leader of Miletus, and of the revolt, and he left Miletus. Herodotus, who evidently has a rather negative view of him, suggests that Aristagoras simply lost his nerve and fled.Herodotu

V, 124–126

/ref> By the sixth year of the revolt (494 BC), the Persian forces had regrouped. The available land forces were gathered into one army, and were accompanied by a fleet supplied by the re-subjugated Cypriots, and the

VI, 6

/ref> The Persians were uncertain of victory at Lade, so attempted to persuade some of the Ionian contingents to defect.Herodotu

VI, 9

/ref> Although this was unsuccessful at first, when the Persians finally attacked the Ionians, the Samian contingent accepted the Persian offer. As the Persian and Ionian fleets met, the Samians sailed away from the battle, causing the collapse of the Ionian battle line.Herodotu

VI, 13

/ref> Although the Chian contingent and a few other ships remained, and fought bravely against the Persians, the battle was lost.Herodotu

VI, 14

/ref> With defeat at Lade, the Ionian Revolt was all but ended. The next year, the Persians reduced the last rebel strongholds, and began the process of bringing peace to the region.Herodotu

VI, 31–33

/ref> The Ionian Revolt constituted the first major conflict between

Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest emp ...

of Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

, to conquer the island of Naxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best ab ...

. It was the opening act of the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

, which would ultimately last for 50 years.

Aristagoras had been approached by exiled Naxian aristocrats, who were seeking to return to their island. Seeing an opportunity to bolster his position in Miletus, Aristagoras sought the help of his overlord, the Persian king Darius the Great, and the local satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with cons ...

, Artaphernes

Artaphernes ( el, Ἀρταφέρνης, Old Persian: Artafarna, from Median ''Rtafarnah''), flourished circa 513–492 BC, was a brother of the Achaemenid king of Persia, Darius I, satrap of Lydia from the capital of Sardis, and a Persian gener ...

to conquer Naxos. Consenting to the expedition, the Persians assembled a force of 200 triremes under the command of Megabates.

The expedition quickly descended into a debacle. Aristagoras and Megabates quarreled on the journey to Naxos, and someone (possibly Megabates) informed the Naxians of the imminent arrival of the force. When they arrived, the Persians and Ionians were thus faced with a city well prepared to undergo siege. The expeditionary force duly settled down to besiege the defenders, but after four months without success, ran out of money and were forced to return to Asia Minor.

In the aftermath of this disastrous expedition, and sensing his imminent removal as tyrant, Aristagoras chose to incite the whole of Ionia into rebellion against Darius the Great. The revolt then spread to Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid- Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joine ...

and Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

. Three years of Persian campaigning across Asia Minor followed, with no decisive effect, before the Persians regrouped and made straight for the epicentre of the rebellion at Miletus. At the Battle of Lade

The Battle of Lade ( grc, Ναυμαχία τῆς Λάδης, translit=Naumachia tēs Ladēs) was a naval battle which occurred during the Ionian Revolt, in 494 BC. It was fought between an alliance of the Ionian cities (joined by the Lesbi ...

, the Persians decisively defeated the Ionian fleet and effectively ended the rebellion. Although Asia Minor had been brought back into the Persian fold, Darius vowed to punish Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

and Eretria

Eretria (; el, Ερέτρια, , grc, Ἐρέτρια, , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th centur ...

, who had supported the revolt. In 492 BC therefore the first Persian invasion of Greece

The first Persian invasion of Greece, during the Greco-Persian Wars, began in 492 BC, and ended with the decisive Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The invasion, consisting of two distinct campaigns, was ordered by ...

would begin as a consequence of the failed attack on Naxos, and the Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisf ...

.

Background

In theGreek Dark Ages

The term Greek Dark Ages refers to the period of History of Greece, Greek history from the end of the Mycenaean civilization, Mycenaean palatial civilization, around 1100 BC, to the beginning of the Archaic Greece, Archaic age, around 750 ...

that followed the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland ...

, significant numbers of Greeks had emigrated to Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and settled there. These settlers were from three tribal groups: the Aeolians

The Aeolians (; el, Αἰολεῖς) were one of the four major tribes in which Greeks divided themselves in the ancient period (along with the Achaeans, Dorians and Ionians)..

Name

Their name mythologically derives from Aeolus, the mythical a ...

, Dorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ioni ...

and Ionians

The Ionians (; el, Ἴωνες, ''Íōnes'', singular , ''Íōn'') were one of the four major tribes that the Greeks considered themselves to be divided into during the ancient period; the other three being the Dorians, Aeolians, and Achaea ...

.HerodotuI, 142–151

/ref> The Ionians had settled about the coasts of

Lydia

Lydia ( Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the modern western Turkish pro ...

and Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid- Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joine ...

, founding the twelve cities which made up Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionia ...

. These cities were Miletus

Miletus (; gr, Μῑ́λητος, Mī́lētos; Hittite transcription ''Millawanda'' or ''Milawata'' ( exonyms); la, Mīlētus; tr, Milet) was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in ...

, Myus

Myus ( grc, Μυοῦς), sometimes Myous or Myos, was an ancient Greek city in Caria. It was one of twelve major settlements of the Ionian League. The city was said to have been founded by Cyaretus ( grc, Κυάρητος) (sometimes called C ...

and Priene

Priene ( grc, Πριήνη, Priēnē; tr, Prien) was an ancient Greek city of Ionia (and member of the Ionian League) located at the base of an escarpment of Mycale, about north of what was then the course of the Maeander River (now called th ...

in Caria; Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built i ...

, Colophon, Lebedos

Lebedus or Lebedos ( grc, Λέβεδος) was one of the twelve cities of the Ionian League, located south of Smyrna, Klazomenai and neighboring Teos and before Ephesus, which is further south. It was on the coast, ninety stadia (16.65 km) ...

, Teos

Teos ( grc, Τέως) or Teo was an ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, on a peninsula between Chytrium and Myonnesus. It was founded by Minyans from Orchomenus, Ionians and Boeotians, but the date of its foundation is unknown. Teos was ...

, Clazomenae

Klazomenai ( grc, Κλαζομεναί) or Clazomenae was an ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia and a member of the Ionian League. It was one of the first cities to issue silver coinage. Its ruins are now located in the modern town Urla ...

, Phocaea

Phocaea or Phokaia (Ancient Greek: Φώκαια, ''Phókaia''; modern-day Foça in Turkey) was an ancient Ionian Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia. Greek colonists from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, in ...

and Erythrae

Erythrae or Erythrai ( el, Ἐρυθραί) later Litri, was one of the twelve Ionian cities of Asia Minor, situated 22 km north-east of the port of Cyssus (modern name: Çeşme), on a small peninsula stretching into the Bay of Erythra ...

in Lydia; and the islands of Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a sepa ...

and Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mast ...

.HerodotuI, 142

/ref> The cities of Ionia had remained independent until they were conquered by the famous Lydian king

Croesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was r ...

, in around 560 BC.HerodotuI, 26

/ref> The Ionian cities then remained under Lydian rule until Lydia was in turn conquered by the nascent

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

.HerodotuI, 141

/ref> The Persians found the Ionians difficult to rule. Elsewhere in the empire, Cyrus was able to identify elite native groups to help him rule his new subjects—such as the priesthood of Judea. No such group existed in Greek cities at this time; while there was usually an aristocracy, this was inevitably divided into feuding factions.Holland, pp. 147–151. The Persians thus settled for the sponsoring a

tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

in each Ionian city, even though this drew them into the Ionians' internal conflicts. Furthermore, a tyrant might develop an independent streak, and have to be replaced. The tyrants themselves faced a difficult task; they had to deflect the worst of their fellow citizens' hatred, while staying in the favour of the Persians.

About 40 years after the Persian conquest of Ionia, and in the reign of the fourth Persian king,

About 40 years after the Persian conquest of Ionia, and in the reign of the fourth Persian king, Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

, the stand-in Milesian tyrant Aristagoras found himself in this familiar predicament.Holland, pp. 153–154. Aristagoras's uncle Histiaeus had accompanied Darius on campaign in 513 BC, and when offered a reward, had asked for part of the conquered Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

territory. Although this was granted, Histiaeus's ambition alarmed Darius's advisors, and Histiaeus was thus further 'rewarded' by being compelled to remain in Susa

Susa ( ; Middle elx, 𒀸𒋗𒊺𒂗, translit=Šušen; Middle and Neo- elx, 𒋢𒋢𒌦, translit=Šušun; Neo- Elamite and Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼𒀭, translit=Šušán; Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼, translit=Šušá; fa, شوش ...

as Darius's "Royal Table-Companion". Taking over from Histiaeus, Aristagoras was faced with bubbling discontent in Miletus.

Indeed, this period in Greek history is remarkable for the social and political upheaval in many Greek cities, particularly the establishment of the first democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

.Finepp. 269–277.

/ref> The island of

Naxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best ab ...

, part of the Cyclades

The Cyclades (; el, Κυκλάδες, ) are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The name ...

group in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

, was also in this period affected by political turmoil. Naxos had been ruled by the tyrant Lygdamis, a protege of the Athenian tyrant Peisistratos

Pisistratus or Peisistratus ( grc-gre, Πεισίστρατος ; 600 – 527 BC) was a politician in ancient Athens, ruling as tyrant in the late 560s, the early 550s and from 546 BC until his death. His unification of Attica, the triangular ...

, until around 524 BC, when he was overthrown by the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

ns. After this, a native aristocracy seems to have flourished, and Naxos became one of the most prosperous and powerful of the Aegean islands.HerodotuV, 28

/ref> Despite its success, Naxos was not immune to class tensions and internal strife, and shortly before 500 BC, the population seized power, expelling the aristocrats and establishing a democracy.Lloyd, p. 143. In 500 BC, Aristagoras was approached by some of the exiles from

Naxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best ab ...

, who asked him to help restore them to the control of the island.HerodotuV, 30

/ref> Seeing an opportunity to strengthen his position in Miletus by conquering Naxos, Aristagoras approached the

satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with cons ...

of Lydia, Artaphernes

Artaphernes ( el, Ἀρταφέρνης, Old Persian: Artafarna, from Median ''Rtafarnah''), flourished circa 513–492 BC, was a brother of the Achaemenid king of Persia, Darius I, satrap of Lydia from the capital of Sardis, and a Persian gener ...

, with a proposal. If Artaphernes provided an army, Aristagoras would conquer the island in Darius's name, and he would then give Artaphernes a share of the spoils to cover the cost of raising the army.HerodotuV, 31

/ref> Furthermore, Aristagoras suggested that once Naxos fell, the other Cyclades would also quickly follow, and he even suggested that

Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poi ...

could be attacked on the same expedition. Artaphernes agreed in principle, and asked Darius for permission to launch the expedition. Darius assented to this, and a force of 200 triremes was assembled in order to attack Naxos the following year.HerodotuV, 32

/ref>

Prelude

The Persian fleet was duly assembled in the spring of 499 BC, and sailed to Ionia. Artaphernes put his (and Darius's) cousin Megabates in charge of the expedition, and dispatched him to Miletus with the Persian army. They were joined there by Aristagoras and the Milesian forces, and then embarked and set sail. In order to avoid warning the Naxians, the fleet initially sailed north, towards theHellespont

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

, but when they arrived at Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mast ...

they doubled back and headed south for Naxos.HerodotuV, 33

/ref>

Herodotus recounts that Megabates made inspections of the ships (probably whilst beached for the night), and came across one ship from Myndus which had not posted any sentries. Megabates ordered his guard to find the captain of the ship, Scylax, and then had the captain thrust into one of the ship's oar holes with his head outside and his body inside the ship. News reached Aristagoras of the treatment of his friend and he went to Megabates and asked him to reconsider his decision. When Megabates refused to grant Aristagoras's wishes, Aristagoras simply cut the captain loose himself. Predictably, Megabates was furious with Aristagoras, who in turn retorted "But you, what have you to do with these matters? Did not Artaphernes send you to obey me and to sail wherever I bid you? Why are you so meddlesome?". According to Herodotus, Megabates was so enraged by this that he sent messengers to the Naxians to warn them of the approach of the Persian force.

Modern historians, doubting that a Persian commander would have sabotaged his own invasion, have suggested several other possible scenarios. It is, however, impossible to know exactly how the Naxians became aware of the invasion, but undoubtedly they were aware, and began to make preparations.Keaveney, p. 76. Herodotus tells us that the Naxians had previously had no inkling of the expedition, but that when news arrived they brought everything in from the fields, gathered enough food with which to survive a siege and reinforced their walls.Herodotu

Herodotus recounts that Megabates made inspections of the ships (probably whilst beached for the night), and came across one ship from Myndus which had not posted any sentries. Megabates ordered his guard to find the captain of the ship, Scylax, and then had the captain thrust into one of the ship's oar holes with his head outside and his body inside the ship. News reached Aristagoras of the treatment of his friend and he went to Megabates and asked him to reconsider his decision. When Megabates refused to grant Aristagoras's wishes, Aristagoras simply cut the captain loose himself. Predictably, Megabates was furious with Aristagoras, who in turn retorted "But you, what have you to do with these matters? Did not Artaphernes send you to obey me and to sail wherever I bid you? Why are you so meddlesome?". According to Herodotus, Megabates was so enraged by this that he sent messengers to the Naxians to warn them of the approach of the Persian force.

Modern historians, doubting that a Persian commander would have sabotaged his own invasion, have suggested several other possible scenarios. It is, however, impossible to know exactly how the Naxians became aware of the invasion, but undoubtedly they were aware, and began to make preparations.Keaveney, p. 76. Herodotus tells us that the Naxians had previously had no inkling of the expedition, but that when news arrived they brought everything in from the fields, gathered enough food with which to survive a siege and reinforced their walls.HerodotuV, 34

/ref>

Opposing forces

Herodotus does not provide complete numbers for either side, but gives some idea of the strength of the two forces. Clearly, since they were fighting on home territory, the Naxian forces could theoretically have included the whole population. Herodotus says in his narrative that the "Naxians have eight thousand men that bear shields", which suggests that there were 8,000 men capable of equipping themselves ashoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The ...

s. These men would have formed a strong backbone to the Naxian resistance.

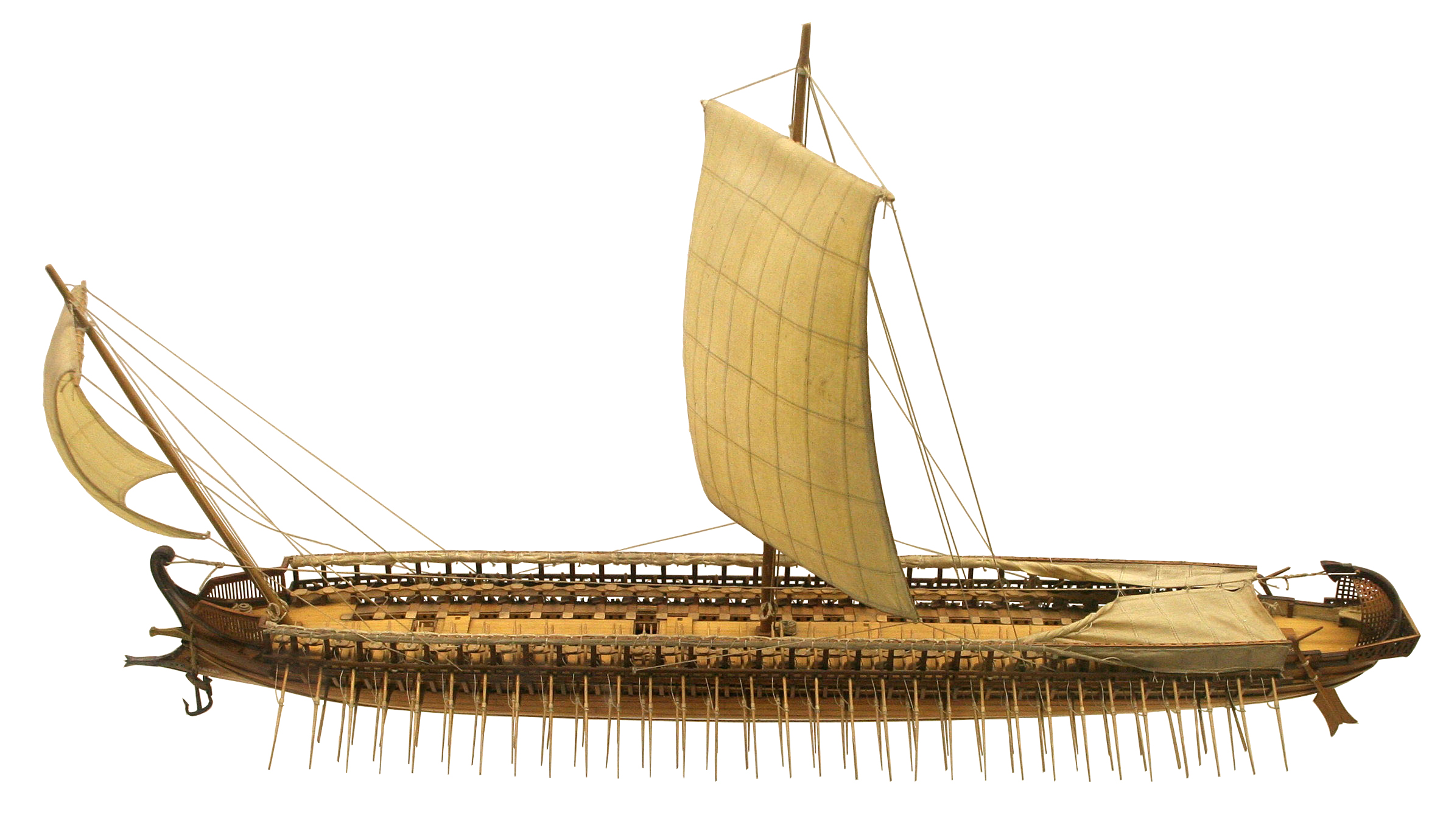

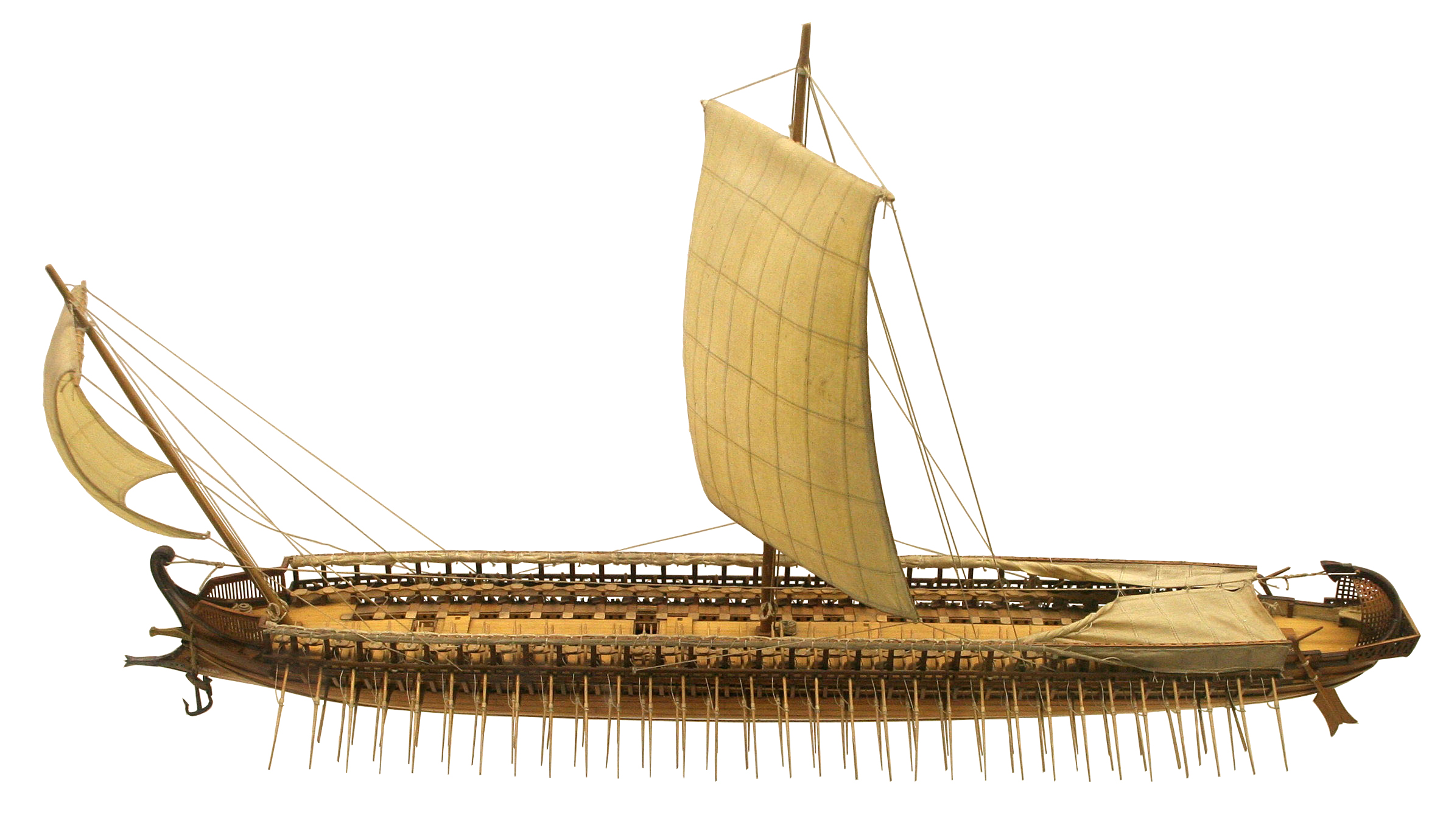

The Persian force was primarily based around 200 trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizat ...

s. It is not clear whether there were additional transport ships. The standard complement of a trireme was 200 men, including 14 marines.Lazenby, p. 46. In the second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasio ...

, each Persian ship had carried thirty extra marines,HerodotuVII, 184

/ref> and this was probably also true in the first invasion when the whole invasion force was apparently carried in triremes. Furthermore, the Chian ships at the

Battle of Lade

The Battle of Lade ( grc, Ναυμαχία τῆς Λάδης, translit=Naumachia tēs Ladēs) was a naval battle which occurred during the Ionian Revolt, in 494 BC. It was fought between an alliance of the Ionian cities (joined by the Lesbi ...

also carried 40 marines each. This suggests that a trireme could probably carry a maximum of 40–45 soldiers—triremes seem to have been easily destabilised by extra weight.Goldsworthy, p. 103. If the Persian force at Naxos was similarly made up, then it would have contained somewhere in the region of 8,000 to 9,000 soldiers (in addition to many unarmed rowers).

Siege

When the Ionians and Persians arrived at Naxos, they were faced by a well-fortified and supplied city. Herodotus does not explicitly say, but this was presumably the eponymous capital of Naxos. He provides few details of the military actions that ensued, although there is a suggestion that there was an initial assault on the city, which was repelled. The Ionians and Persians thus settled down to besiege the city. However, after four months, the Persians had run out of money, with Aristagoras also spending a great deal. Thoroughly demoralised, the expedition prepared to return to Asia Minor empty handed. Before leaving, they built a stronghold for the exiled Naxian aristocrats on the island. This was a typical strategy in the Greek world for those exiled by internal strife, giving them a base from which to quickly return, as events permitted.

When the Ionians and Persians arrived at Naxos, they were faced by a well-fortified and supplied city. Herodotus does not explicitly say, but this was presumably the eponymous capital of Naxos. He provides few details of the military actions that ensued, although there is a suggestion that there was an initial assault on the city, which was repelled. The Ionians and Persians thus settled down to besiege the city. However, after four months, the Persians had run out of money, with Aristagoras also spending a great deal. Thoroughly demoralised, the expedition prepared to return to Asia Minor empty handed. Before leaving, they built a stronghold for the exiled Naxian aristocrats on the island. This was a typical strategy in the Greek world for those exiled by internal strife, giving them a base from which to quickly return, as events permitted.

Aftermath

With the failure of his attempt to conquer Naxos, Aristagoras found himself in dire straits; he was unable to repay Artaphernes the costs of the expedition, and had moreover alienated himself from the Persian royal family. He fully expected to be stripped of his position by Artaphernes. In a desperate attempt to save himself, Aristagoras chose to incite his own subjects, the Milesians, to revolt against their Persian masters, thereby beginning the Ionian Revolt.HerodotuV, 35

/ref> Although Herodotus presents the revolt as a consequence of Aristagoras' personal motives, it is clear that Ionia must have been ripe for rebellion anyway, the primary grievance being the tyrants installed by the Persians. Aristagoras's actions have thus been likened to tossing a flame into a kindling box; they incited rebellion across Ionia (and

Aeolis

Aeolis (; grc, Αἰολίς, Aiolís), or Aeolia (; grc, Αἰολία, Aiolía, link=no), was an area that comprised the west and northwestern region of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), mostly along the coast, and also several offshore islan ...

and Doris), and tyrannies were everywhere abolished, and democracies established in their place.Holland, pp. 155–157.

Having brought all of Hellenic Asia Minor into revolt, Aristagoras evidently realised that the Greeks would need other allies in order to fight the Persians.Holland, pp. 157–159. In the winter of 499 BC, he sailed to mainland Greece to try to recruit allies. He failed to persuade the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

ns, but the cities of Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

and Eretria

Eretria (; el, Ερέτρια, , grc, Ἐρέτρια, , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th centur ...

agreed to support the rebellion. In the spring of 498 BC, an Athenian force of twenty triremes, accompanied by five from Eretria, for a total of twenty-five triremes, set sail for Ionia.Holland, pp. 160–162. They joined up with the main Ionian force near Ephesus.HerodotuV, 100

/ref> This force was then guided by the Ephesians through mountains to

Sardis

Sardis () or Sardes (; Lydian: 𐤳𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣 ''Sfard''; el, Σάρδεις ''Sardeis''; peo, Sparda; hbo, ספרד ''Sfarad'') was an ancient city at the location of modern ''Sart'' (Sartmahmut before 19 October 2005), near Salihli, ...

, Artaphernes's satrapal capital. The Greeks caught the Persians unawares, and were able to capture the lower city. However, the lower city then caught on fire, and the Greeks, demoralised, then retreated from the city, and began to make their way back to Ephesus.HerodotuV, 101

/ref> The Persian troops in Asia Minor followed the Greek force, catching them outside Ephesus. It is clear that the demoralised and tired Greeks were no match for the Persians, and were completely routed in the battle which ensued at Ephesus. The Ionians who escaped the battle made for their own cities, while the remaining Athenians and Eretrians managed to return to their ships, and sailed back to Greece.Herodotu

V, 102

/ref>

Despite these setbacks, the revolt spread further. The Ionians sent men to the

Despite these setbacks, the revolt spread further. The Ionians sent men to the Hellespont

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

and Propontis, and captured Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium' ...

and the other nearby cities. They also persuaded the Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid- Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joine ...

ns to join the rebellion.HerodotuV, 103

/ref> Furthermore, seeing the spread of the rebellion, the kingdoms of

Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

also revolted against Persian rule without any outside persuasion.HerodotuV, 104

/ref> For the next three years, the Persian army and navy were fully occupied with fighting the rebellions in Caria and Cyprus, and Ionia seems to have had an uneasy peace during these years.Boardman ''et al''

pp. 481–490.

/ref> At the height of the Persian counter-offensive, Aristagoras, sensing the untenability of his position, decided to abandon his position as leader of Miletus, and of the revolt, and he left Miletus. Herodotus, who evidently has a rather negative view of him, suggests that Aristagoras simply lost his nerve and fled.Herodotu

V, 124–126

/ref> By the sixth year of the revolt (494 BC), the Persian forces had regrouped. The available land forces were gathered into one army, and were accompanied by a fleet supplied by the re-subjugated Cypriots, and the

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

ians, Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern co ...

ns and Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns. The Persians headed directly to Miletus, paying little attention to other strongholds, presumably intending to tackle the revolt at its centre. The Ionians sought to defend Miletus by sea, leaving the defense of Miletus to the Milesians. The Ionian fleet gathered at the island of Lade, off the coast of Miletus

Miletus (; gr, Μῑ́λητος, Mī́lētos; Hittite transcription ''Millawanda'' or ''Milawata'' ( exonyms); la, Mīlētus; tr, Milet) was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in ...

.HerodotuVI, 6

/ref> The Persians were uncertain of victory at Lade, so attempted to persuade some of the Ionian contingents to defect.Herodotu

VI, 9

/ref> Although this was unsuccessful at first, when the Persians finally attacked the Ionians, the Samian contingent accepted the Persian offer. As the Persian and Ionian fleets met, the Samians sailed away from the battle, causing the collapse of the Ionian battle line.Herodotu

VI, 13

/ref> Although the Chian contingent and a few other ships remained, and fought bravely against the Persians, the battle was lost.Herodotu

VI, 14

/ref> With defeat at Lade, the Ionian Revolt was all but ended. The next year, the Persians reduced the last rebel strongholds, and began the process of bringing peace to the region.Herodotu

VI, 31–33

/ref> The Ionian Revolt constituted the first major conflict between

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

and the Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest emp ...

, and as such represents the first phase of the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

. Although Asia Minor had been brought back into the Persian fold, Darius vowed to punish Athens and Eretria for their support for the revolt. Moreover, seeing that the myriad city states of Greece posed a continued threat to the stability of his empire, he decided to conquer the whole of Greece. In 492 BC, the first Persian invasion of Greece

The first Persian invasion of Greece, during the Greco-Persian Wars, began in 492 BC, and ended with the decisive Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The invasion, consisting of two distinct campaigns, was ordered by ...

, the next phase of the Greco-Persian Wars, would begin as a direct consequence of the Ionian Revolt.Holland, pp. 175–177.

References

Bibliography

Ancient sources

*Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

, '' The Histories'' (Godley translation, 1920)

*Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

, ''History of The Peloponnesian Wars''

*Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

, ''Library''

*Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

, ''On the Laws''

Modern Sources

* * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Naxos 499 BC Ionian Revolt Battles involving ancient GreeceNaxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best ab ...

Battles of the Greco-Persian Wars

490s BC conflicts

S

499 BC