Scathophaga stercoraria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Scathophaga stercoraria'', commonly known as the yellow dung fly or the golden dung fly, is one of the most familiar and abundant

Yellow dung flies are

Yellow dung flies are

Jim Lindsey's page on yellow dung flies

{{Taxonbar, from=Q28120 Scathophagidae Coprophagous insects Diptera of Asia Diptera of North America Muscomorph flies of Europe Insects described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

flies

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced m ...

in many parts of the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

. As its common name suggests, it is often found on the feces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a rela ...

of large mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

s, such as horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

s, cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ...

, sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticate ...

, deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the re ...

, and wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The species i ...

, where it goes to breed. The distribution of ''S. stercoraria'' is likely influenced by human agriculture, especially in northern Europe and North America. The ''Scathophaga'' are integral in the animal kingdom due to their role in the natural decomposition of dung in fields. They are also very important in the scientific world due to their short life cycles and susceptibility to experimental manipulations; thus, they have contributed significant knowledge about animal behavior.

Description

''Scathophaga stercoraria'' issexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

, with an average lifespan of one to two months. The adult males are bright golden-yellow with orange-yellow fur on the front legs. Females are a little duller in color, with pronounced green-brown tinges, and no brightly colored fur on the front legs. The adults range from 5 to 11 mm in length, and the males are generally larger than the females. The physical features of separate ''S. stercoraria'' populations can vary greatly, due in part to the range of locations in which the species is found. Generally, they are located in cooler temperate regions, including North America, Asia, and Europe. They may also favor higher altitudes, such as the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

and Swiss Alps

The Alpine region of Switzerland, conventionally referred to as the Swiss Alps (german: Schweizer Alpen, french: Alpes suisses, it, Alpi svizzere, rm, Alps svizras), represents a major natural feature of the country and is, along with the Swis ...

.

Feeding

The adults mainlyprey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

on smaller insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three pa ...

s—mostly other Diptera

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced ...

. They can also consume nectar and dung as additional sources of energy. In a laboratory setting, adult ''S. stercoraria'' can live solely on ''Drosophila

''Drosophila'' () is a genus of flies, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or (less frequently) pomace flies, vinegar flies, or wine flies, a reference to the characteristic of many speci ...

'' and water. Females spend most of their time foraging in vegetation and only visit dung pats to mate and oviposit

The ovipositor is a tube-like organ used by some animals, especially insects, for the laying of eggs. In insects, an ovipositor consists of a maximum of three pairs of appendages. The details and morphology of the ovipositor vary, but typical ...

on the dung surface. Both males and females are attracted to dung by scent, and approach dung pats against the wind. Males spend most of their time on the dung, waiting for females and feeding on other insects that visit the dung, such as blow flies. In the absence of other prey, the yellow dung fly may turn to cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

. The larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

...

e are coprophagous

Coprophagia () or coprophagy () is the consumption of feces. The word is derived from the grc, κόπρος , "feces" and , "to eat". Coprophagy refers to many kinds of feces-eating, including eating feces of other species (heterospecifics), of ...

, relying on dung for nutrition.

Reproduction

''Scathophaga stercoraria'' breeds on the dung of many large mammals, but generally prefers fresh cattle dung. Theoperational sex ratio In the evolutionary biology of sexual reproduction, operational sex ratio (OSR) is the ratio of sexually competing males that are ready to mate to sexually competing females that are ready to mate, or alternatively the local ratio of fertilizable fe ...

on these pats is very male-biased and competition is high. Females are small and have limited precopulatory choice. Copulation

Sexual intercourse (or coitus or copulation) is a sexual activity typically involving the insertion and thrusting of the penis into the vagina for sexual pleasure or reproduction.Sexual intercourse most commonly means penile–vaginal penetra ...

lasts 20–50 minutes, after which the male attempts to guard the female from other males. Both males and females often mate with multiple partners. Reproductive success depends on a variety of factors, including sperm competition, nutrition, and environmental temperature.

Anatomy

Females have pairedaccessory glands

Male accessory glands (MAG) in humans are the seminal vesicles, prostate gland, and the bulbourethral glands (also called Cowper's glands).

In insects, male accessory glands produce products that mix with the sperm to protect and preserve them, in ...

, which supply lubricants to the reproductive system and secrete protein-rich egg shells. Sperm is received in a large structure called the bursa copulatrix, and is stored in a structure called the spermatheca. ''Scathophaga'' species have three spermathecae, (one pair and one singlet), each with its own narrow duct that connects it to the bursa. Sperm can be stored in the spermathecae for days, weeks, or even years, and sperm from several males can be stored simultaneously.

Males have two projections, the paralobes, which are used to hold onto a female during copulation. Between the paralobes is the intromittent organ

An intromittent organ is any external organ of a male organism that is specialized to deliver sperm during copulation. Intromittent organs are found most often in terrestrial species, as most non-mammalian aquatic species fertilize their eggs e ...

, the aedeagus

An aedeagus (plural aedeagi) is a reproductive organ of male arthropods through which they secrete sperm from the testes during copulation with a female. It can be thought of as the insect equivalent of a mammal's penis, though the comparison i ...

, which transfers sperm into the female's bursa copulatrix.

Behavior

During copulation,sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, ...

is not directly deposited into sperm-storing organs. Ejaculation occurs in the bursa copulatrix, and then females actively move sperm into the spermathecae using their muscular spermathecal invagination to pump sperm into transit. This gives females a level of control over which and how much sperm enters her system, an example of cryptic female choice. Although current results are inconclusive regarding whether or not females are cryptically selecting for a better phenotypic match, a female may benefit from having variable sperm fertilizing her offspring. Such adaptations are advantageous because females benefit from being able to control which sperm are successful in fertilizing eggs. The females may not be aware of which sperm are better suited for her offspring, but simply that being able to control the proportion of sperm from multiple mates can maximize the possibility of an optimal phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological pr ...

match. It is to her advantage to have multiple males’ sperm reach her eggs, rather than just one.

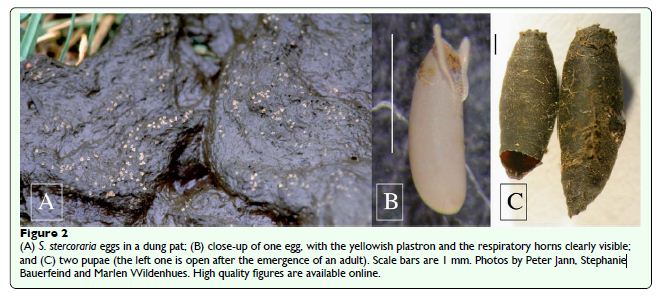

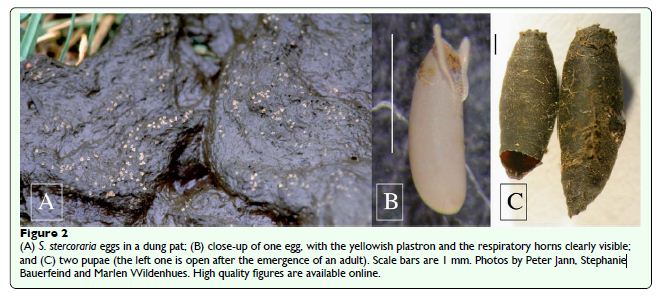

After copulation, females prefer to lay their eggs on the small hills of the dung surface, avoiding depressions and pointed areas. This survival strategy aims to prevent desiccation and drowning so the eggs are placed where they have the greatest chance of surviving.

Sexual conflict

Many studies have studied the many manifestations of sexual conflict, including post-mating sexual selection, in the yellow dung fly. Sperm competition occurs when a female mates with multiple males. Each male's sperm is then in direct competition to fertilize the eggs. Sperm mix quickly once they reach the female's stores. The goal of males is to displace the sperm of other males as much as possible. Larger males tend to have longer copulation times and greater rates of sperm displacement. The fertilization success of males that were secondary mates increased as their body size relative to the first male increased. Traits such as body size, testis size, and sperm length are variable, as well as heritable in ''S. stercoraria'' males. Larger sperm may be advantageous if they have greater propulsion along the female's spermathecal duct, resulting in higher fertilization success rates. When competition among males is high and females are mating with multiple males, those with the largest testes also have the most success in terms of proportion of sperm that fertilize a female's eggs. The resulting male offspring would then have a similar advantage. A positive correlation was found between sperm length of males and spermathecal duct length of females. The size of male testis was also positively correlated with female spermathecae size. Additionally, females with larger spermathecae are better able to producespermicidal

Spermicide is a contraceptive substance that destroys sperm, inserted vaginally prior to intercourse to prevent pregnancy. As a contraceptive, spermicide may be used alone. However, the pregnancy rate experienced by couples using only spermici ...

secretion. This cryptic female choice betters their ability to influence paternity over their offspring. These covariances are an example of an “evolutionary arms race

In evolutionary biology, an evolutionary arms race is an ongoing struggle between competing sets of co-evolving genes, phenotypic and behavioral traits that develop escalating adaptations and counter-adaptations against each other, resembling an ...

”. This suggests that each sex evolves certain traits to undermine the beneficial traits of the other, resulting in the coevolution

In biology, coevolution occurs when two or more species reciprocally affect each other's evolution through the process of natural selection. The term sometimes is used for two traits in the same species affecting each other's evolution, as well ...

of male and female reproductive systems of ''S. stercoraria.''

Life cycle

The eggs that the female lays on the dung hatch intolarvae

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

T ...

after 1–2 days, depending on temperature. The larvae quickly burrow into the dung for protection and feed on it. At 20 °C, larvae undergo three molts over five days, during which they grow exponentially. After growth, larvae spend another five days emptying their stomachs before pupation

A pupa ( la, pupa, "doll"; plural: ''pupae'') is the life stage of some insects undergoing transformation between immature and mature stages. Insects that go through a pupal stage are holometabolous: they go through four distinct stages in thei ...

, where no additional body mass is gained. After 10–20 days, the larvae burrow into the soil around and beneath the dung and pupate

A pupa ( la, pupa, "doll"; plural: ''pupae'') is the life stage of some insects undergoing transformation between immature and mature stages. Insects that go through a pupal stage are holometabolous: they go through four distinct stages in their ...

. The time needed for the juvenile flies to emerge can vary from 10 days at 25 °C to 80 days at 10 °C or less. The smaller females typically emerge a few days before the males. The fitness of the resulting juveniles is greatly dependent on the quality of the dung in which they were placed. Factors affecting dung quality include water content, nutritional quality, parasites, and drugs or other chemicals given to the animal.  Yellow dung flies are

Yellow dung flies are anautogenous

In entomology, anautogeny is a reproductive strategy in which an adult female insect must eat a particular sort of meal (generally vertebrate blood) before laying eggs in order for her eggs to mature. This behavior is most common among diptera ...

. To become sexually mature and produce viable eggs or sperm, they must feed on prey to acquire sufficient proteins and lipids. Females under nutritional stress will have higher rates of egg mortality and less survival of offspring to adult emergence. ''S. stercoraria'' females can then produce four to 10 clutches in their lifetimes. The adults are active throughout much of the year in most moderate climates.

Phenology

Yellow dung fly viability depends strongly on the environment. In warmer climates, a sharp population decline often occurs in the summer, when the temperatures increase above 25 °C. Meanwhile, no population decline is seen in colder climates, such asIceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

, Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

, and northern England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, and high elevations. Additionally, the number of generations per year varies with altitude

Altitude or height (also sometimes known as depth) is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context ...

and latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north ...

, typically between two and four overlapping generations. The end of winter synchronizes the first emergence in March, and the overwinter generations are produced in the fall. In northern Europe, where the mating season is shorter, only one or two generations can be expected.

Phenotypic plasticity

Yellow dung flies have extremely variablephenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (biology), morphology or physical form and structure, its Developmental biology, developmental proc ...

s - body size and development rate in particular. Proximate causes of variation include juvenile nutrition, temperature, predation

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

, and genetic variation

Genetic variation is the difference in DNA among individuals or the differences between populations. The multiple sources of genetic variation include mutation and genetic recombination. Mutations are the ultimate sources of genetic variation, b ...

. Much phenotypic plasticity

Phenotypic plasticity refers to some of the changes in an organism's behavior, morphology and physiology in response to a unique environment. Fundamental to the way in which organisms cope with environmental variation, phenotypic plasticity encompa ...

in yellow dung flies is a result of food (dung) availability in the larval stage, which is often mediated by conspecific

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organis ...

competition. Less dung results in more competitors, and more drying results in decreased growth rate and adult body size. Additionally, when exposed to constant temperatures in a laboratory setting, higher temperatures during growth yield smaller flies. Egg volume, but not clutch size, also decreases with increasing temperature. Giving merit to the hypothesis that constraints on physiological processes at the cellular level account for temperature-mediated body size, studies have also shown that ''S. stercoraria'' body size varies via gene-by-environment interactions. Different cell lines vary significantly in growth, development, and adult body size in response to food limitation.

Geographic variation

''Scathophaga stercoraria's'' phenotype has been shown to vary seasonally, latitudinally, and altitudinally as a result of an adaptive response to time constraints on development due to temperature changes. In the fall, as the temperature cools, the flies are able to increase development rate, so they can achieve the necessary, albeit smaller than average, size. Furthermore, ''S. stercoraria'' development rate increases with increasing latitude. This is likely an adaptive response to shorter mating seasons. Body size, but not development rate, vary with altitude. Dung flies are larger at higher altitudes as a result of colder temperatures.Reasons behind phenotypic plasticity

Larger yellow dung flies have a competitive advantage. Therefore, body size plasticity must be a survival mechanism. Offspring of large adults still survive under food limitations, despite needing more nutrients for a longer development. Thus, the observed growth plasticity is a result of altering body chemistry and not differing survival rates of offspring from small and large parents. Plastic development rate and body size are effective at avoiding premature death, meaning ''S. stercoraria'' adopts a strategy of being small and alive over large and dead. Smaller flies have an advantage in stressful environmental situations, due to larger dung flies needing more energy. Additionally, low genetic differentiation exists between yellow dung fly populations, likely due to extensive gene flow, as ''S. stercoraria'' is able to travel great distances. When species are unable to adapt through genetics, phenotypic plasticity is the most viable option to adjust to changing environments. Yellow dung flies develop in extremely variable environments, with pat drying, dung availability, and larval competition hindering survival. Therefore, phenotypic plasticity allows ''S. stercoraria'' to adjust development according to unpredictableecological

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overlaps wi ...

situations without genetic adaptation.

Parasites and diseases

Since ''S. stercoraria'' is asynanthropic

A synanthrope (from the Greek σύν ''syn'', "together with" + ἄνθρωπος ''anthropos'', "man") is a member of a species of wild animal or plant that lives near, and benefits from, an association with human beings and the somewhat artific ...

fly, it does carry the risk of passively contaminating human food with various pathogens, molds, or yeasts.

Some sexually transmitted disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and or ...

s of insects are known, particularly in Coleoptera

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describe ...

. Similar diseases have also been studied in ''S. stercoraria''. Many of these sexually transmitted diseases are from multicellular

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially ...

ectoparasites

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

(mites), protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the e ...

s, or the fungus

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately fr ...

''Entomophthora muscae

''Entomophthora muscae'' is a species of pathogenic fungus in the order Entomophthorales which causes a fatal disease in flies. It can cause epizootic outbreaks of disease in houseflies and has been investigated as a potential biological control ...

''. These are frequently responsible for either sterilizing or killing the host fly.

Predators

As well as being an easy meal for a great manybird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

and bat species, these flies are also preyed upon by other insects. Much competition exists between larvae of different species within a dung pat. Other insect species may also use the pats as hunting grounds. These include robber flies

The Asilidae are the robber fly family, also called assassin flies. They are powerfully built, bristly flies with a short, stout proboscis enclosing the sharp, sucking hypopharynx. The name "robber flies" reflects their notoriously aggressive pr ...

and clown beetles.

Use as a model organism

Like ''Drosophila melanogaster

''Drosophila melanogaster'' is a species of fly (the taxonomic order Diptera) in the family Drosophilidae. The species is often referred to as the fruit fly or lesser fruit fly, or less commonly the " vinegar fly" or "pomace fly". Starting with ...

'', the yellow dung fly is an ideal model organism

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workin ...

due to its short lifespan and susceptibility to various experimental manipulations. Initial interest in yellow dung flies came from their potential as biocontrol agents against pest flies around livestock. In the past 40 years alone, many studies have used ''S. stercoraria'' to research topics such as sperm competition, mating behavior, sexual conflict, reproductive physiology, thermal biology, and genetics. In particular, research on yellow dung flies has contributed greatly to understanding of multiple mating systems and sperm competition.

Recently, ''S. stercoraria'' was approved as a standard required test species for ecotoxicological testing. This includes evaluating the residues of veterinary drugs in livestock dung. Yellow dung flies are a key part of decomposing waste in pastures, which is key to preventing the spread of endoparasites and returning nutrients to the soil. The species’ diet also serves to reduce the abundance of pest flies. To test a chemical's toxicity, the chemical is mixed with bovine faeces, to which yellow dung fly eggs are added. Then, endpoints, such as sex and number of emerged adult flies, retardation of emergence, morphological change, and developmental rate, are measured and analyzed to determine toxicity. A great deal of research has been done on the effects of avermectin

The avermectins are a series of drugs and pesticides used to treat parasitic worms and insect pests. They are a group of 16-membered macrocyclic lactone derivatives with potent anthelmintic and insecticidal properties. These naturally occurring c ...

s on populations of ''S. stercoraria''. Avermectins are used to control endoparasites in livestock. The resulting dung contains drug residues that can have unintentional adverse effects on yellow dung fly populations, such as increased mutations and decreased offspring viability. If the use of such drugs in agriculture is not carefully monitored, considerable economic losses could occur.

References

External links

Jim Lindsey's page on yellow dung flies

{{Taxonbar, from=Q28120 Scathophagidae Coprophagous insects Diptera of Asia Diptera of North America Muscomorph flies of Europe Insects described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus