Samaritans (; ; he, שומרונים, translit=Šōmrōnīm, lit=; ar, السامريون, translit=as-Sāmiriyyūn) are an

ethnoreligious group

An ethnoreligious group (or an ethno-religious group) is a grouping of people who are unified by a common religious and ethnic background.

Furthermore, the term ethno-religious group, along with ethno-regional and ethno-linguistic groups, is a ...

who originate from the ancient

Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

. They are native to the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

and adhere to

Samaritanism

Samaritanism is the Abrahamic, monotheistic, ethnic religion of the Samaritan people, an ethnoreligious group who, alongside Jews, originate from the ancient Israelites.

Its central holy text is the Samaritan Pentateuch, which Samaritans ...

, an

Abrahamic

The Abrahamic religions are a group of religions centered around worship of the God of Abraham. Abraham, a Hebrew patriarch, is extensively mentioned throughout Abrahamic religious scriptures such as the Bible and the Quran.

Jewish traditi ...

and

ethnic religion

In religious studies, an ethnic religion is a religion or belief associated with a particular ethnic group. Ethnic religions are often distinguished from universal religions, such as Christianity or Islam, in which gaining converts is a prima ...

.

Samaritan tradition claims the group descends from the northern

Israelite tribes who were not

deported by the

Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew ...

after the destruction of the

Kingdom of Israel

The Kingdom of Israel may refer to any of the historical kingdoms of ancient Israel, including:

Fully independent (c. 564 years)

*Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy) (1047–931 BCE), the legendary kingdom established by the Israelites and uniting ...

. They consider Samaritanism to be the true

religion of the ancient Israelites and regard

Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

as a closely related but altered religion. Samaritans also regard

Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim (; Samaritan Hebrew: ''ʾĀ̊rgā̊rīzēm''; Hebrew: ''Har Gərīzīm''; ar, جَبَل جَرِزِيم ''Jabal Jarizīm'' or جَبَلُ ٱلطُّورِ ''Jabal at-Ṭūr'') is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinit ...

(near both

Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

and biblical

Shechem

Shechem ( ), also spelled Sichem ( ; he, שְׁכֶם, ''Šəḵem''; ; grc, Συχέμ, Sykhém; Samaritan Hebrew: , ), was a Canaanite and Israelite city mentioned in the Amarna Letters, later appearing in the Hebrew Bible as the first c ...

), and not the

Temple Mount

The Temple Mount ( hbo, הַר הַבַּיִת, translit=Har haBayīt, label=Hebrew, lit=Mount of the House f the Holy}), also known as al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, lit. 'The Noble Sanctuary'), al-Aqsa Mosque compou ...

in

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, to be the holiest place on Earth.

They attribute the schism between Samaritanism and Judaism to have been caused by

Eli creating an alternate shrine at

Shiloh, in opposition to Mount Gerizim.

Once a large community, the Samaritan population shrank significantly in the wake of the brutal suppression of the

Samaritan revolts

The Samaritan revolts (c. 484–573) were a series of insurrections in Palaestina Prima province, launched by the Samaritans against the Eastern Roman Empire. The revolts were marked by great violence on both sides, and their brutal suppressio ...

against the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. Mass conversion to

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

under the Byzantines and later to

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

following the

Muslim conquest of the Levant

The Muslim conquest of the Levant ( ar, فَتْحُ الشَّام, translit=Feth eş-Şâm), also known as the Rashidun conquest of Syria, occurred in the first half of the 7th century, shortly after the rise of Islam."Syria." Encyclopædia Br ...

further reduced their numbers. In the 12th century, the Jewish traveler

Benjamin of Tudela

Benjamin of Tudela ( he, בִּנְיָמִין מִטּוּדֶלָה, ; ar, بنيامين التطيلي ''Binyamin al-Tutayli''; Tudela, Kingdom of Navarre, 1130 Castile, 1173) was a medieval Jewish traveler who visited Europe, Asia, an ...

estimated that only around 1,900 Samaritans remained in the regions of

Palestine and

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

. As of 2021, the community stood at around 840 individuals, divided between

Kiryat Luza

Kiryat Luza ( ar, قرية لوزة, he, קרית לוזה) is a Samaritan village situated on Mount Gerizim near the city of Nablus in the West Bank. It is under the joint control of Israel and the Palestinian National Authority, and ...

on Mount Gerizim and the Samaritan compound in

Holon

Holon ( he, חוֹלוֹן ) is a city on the central coastal strip of Israel, south of Tel Aviv. Holon is part of the metropolitan Gush Dan area. In it had a population of . Holon has the second-largest industrial zone in Israel, after Haifa ...

. There are also small populations in

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and elsewhere. The head of the Samaritan community is the

Samaritan High Priest. The Samaritans in Kiryat Luza speak

Levantine Arabic

Levantine Arabic, also called Shami ( autonym: or ), is a group of mutually intelligible vernacular Arabic varieties spoken in the Levant, in Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, and Turkey (historically in Adana, Mersin and Hatay on ...

, while those in Holon primarily speak

Israeli Hebrew. For the purposes of

liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

,

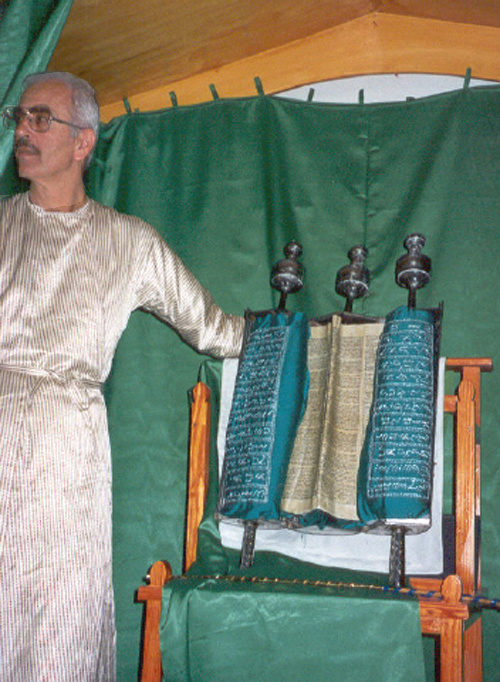

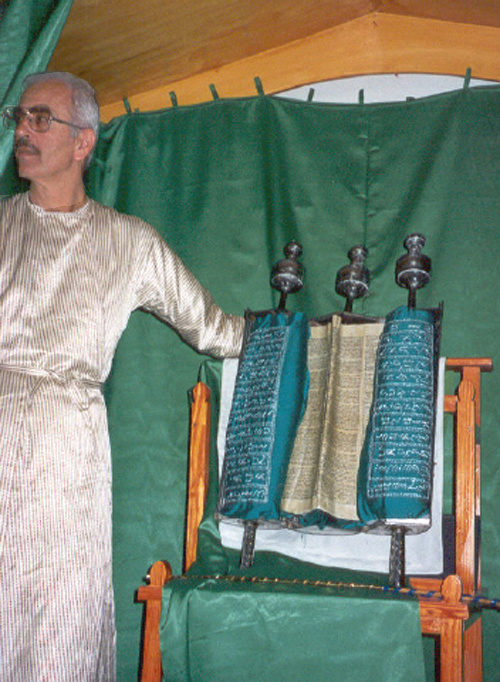

Samaritan Hebrew

Samaritan Hebrew () is a reading tradition used liturgically by the Samaritans for reading the Ancient Hebrew language of the Samaritan Pentateuch, in contrast to Tiberian Hebrew among the Jews.

For the Samaritans, Ancient Hebrew ceased to be ...

and

Samaritan Aramaic

Samaritan Aramaic, or Samaritan, was the dialect of Aramaic used by the Samaritans in their sacred and scholarly literature. This should not be confused with the Samaritan Hebrew language of the Scriptures. Samaritan Aramaic ceased to be ...

are used, both written in the

Samaritan script

The Samaritan script is used by the Samaritans for religious writings, including the Samaritan Pentateuch, writings in Samaritan Hebrew, and for commentaries and translations in Samaritan Aramaic and occasionally Arabic.

Samaritan is a direc ...

.

Samaritans have a standalone

religious status in Israel, and there are occasional conversions from Judaism to Samaritanism and vice versa, largely due to

interfaith marriages. While Israel's

rabbinic authorities came to consider Samaritanism to be a

sect of Judaism, the

Chief Rabbinate of Israel

The Chief Rabbinate of Israel ( he, הָרַבָּנוּת הָרָאשִׁית לְיִשְׂרָאֵל, ''Ha-Rabbanut Ha-Rashit Li-Yisra'el'') is recognized by law as the supreme rabbinic authority for Judaism in Israel. The Chief Rabbinate C ...

requires Samaritans to undergo a formal

conversion to Judaism

Conversion to Judaism ( he, גיור, ''giyur'') is the process by which non-Jews adopt the Jewish religion and become members of the Jewish ethnoreligious community. It thus resembles both conversion to other religions and naturalization. ...

in order to be officially recognized as

Halakhic Jews.

Rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire spectrum of rabbinic writings throughout Jewish history. However, the term often refers specifically to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic w ...

rejected Samaritans unless they renounced Mount Gerizim as the historical Israelite holy site. Samaritans possessing only Israeli citizenship in Holon

are drafted into the

Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

, while those holding dual Israeli and Palestinian citizenship in Kiryat Luza are exempted from mandatory military service.

Etymology and terminology

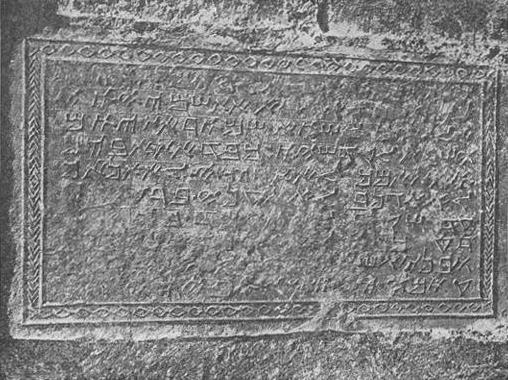

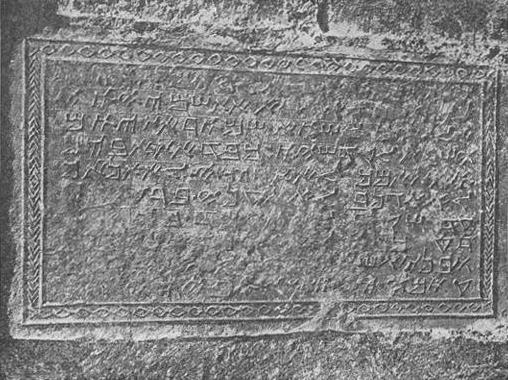

Inscriptions from the Samaritan diaspora in

Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island ar ...

, dating as early as 150-50 BCE, and perhaps slightly earlier, provide the "oldest known self-designation" for Samaritans, indicating that they called themselves "Israelites". Strictly speaking, the Samaritans now refer to themselves generally as 'Israelite Samaritans.'

In

their own language the Samaritans

call themselves ''Shamerim'' (שַמֶרִים), meaning 'Guardians/Keepers/Watchers', and in

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

( ar, السامريون, al-Sāmiriyyūn).

The term is

cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words in different languages that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language. Because language change can have radical ef ...

with the

Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew (, or , ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite branch of Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Israel, roughly west of t ...

term ''Šomerim'', and both terms reflect a

Semitic root

The roots of verbs and most nouns in the Semitic languages are characterized as a sequence of consonants or "radicals" (hence the term consonantal root). Such abstract consonantal roots are used in the formation of actual words by adding the vowels ...

שמר, which means "to watch, guard".

Historically, Samaritans were concentrated in

Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first ...

. In

Modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew ( he, עברית חדשה, ''ʿivrít ḥadašá ', , '' lit.'' "Modern Hebrew" or "New Hebrew"), also known as Israeli Hebrew or Israeli, and generally referred to by speakers simply as Hebrew ( ), is the standard form of the He ...

, the Samaritans are called ''Shomronim'' , which also means "inhabitants of Samaria", literally, "Samaritans".

That the meaning of their name signifies ''Guardians/Keepers/Watchers

Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

'', rather than being a toponym referring to the inhabitants of the region of Samaria, was remarked on by a number of Christian Church fathers, including Epiphanius of Salamis in the ''Panarion'', Jerome and Eusebius in the ''

Chronicon'' and

Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and the ...

in ''The Commentary on Saint John's Gospel.''

Josephus uses several terms for the Samaritans, which he appears to use interchangeably. Among them is reference to ''Khuthaioi'', a designation employed to denote peoples in Media and Persian putatively sent to Samaria to replace the exiled Israelite population. These Khouthaioi were in fact Hellenistic Phoenicians/Sidonians. ''Samareis'' (Σαμαρεῖς) may refer to inhabitants of the region of Samaria, or of the city of that name, though some texts use it to refer specifically to Samaritans.

Origins

The similarities between Samaritans and Jews was such that the rabbis of the

Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Tor ...

found it impossible to draw a clear distinction between the two groups. Attempts to date when the

schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

among Israelites took place, which engendered the division between Samaritans and Judaeans, vary greatly, from the time of

Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe ('' sofer'') and priest ('' kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρ ...

down to the

destruction of Jerusalem (70 CE) and the

Bar Kokhba revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt ( he, , links=yes, ''Mereḏ Bar Kōḵḇāʾ''), or the 'Jewish Expedition' as the Romans named it ( la, Expeditio Judaica), was a rebellion by the Jews of the Roman province of Judea, led by Simon bar Kokhba, ag ...

(132-136 CE). The emergence of a distinctive Samaritan identity, the outcome of a mutual estrangement between them and Jews, was something that developed over several centuries. Generally, a decisive rupture is believed to have taken place in the

Hasmonean period.

Ancestrally, Samaritans affirm that they descend from the tribes of

Ephraim

Ephraim (; he, ''ʾEp̄rayīm'', in pausa: ''ʾEp̄rāyīm'') was, according to the Book of Genesis, the second son of Joseph ben Jacob and Asenath. Asenath was an Ancient Egyptian woman whom Pharaoh gave to Joseph as wife, and the daughte ...

and

Manasseh in ancient

Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first ...

. Samaritan tradition associates the split between them and the

Judean-led Southern Israelites to the time of the biblical priest

Eli, described as a "false" high priest who usurped the priestly office from its occupant, Uzzi, and established a rival shrine at

Shiloh, and thereby prevented southern pilgrims from Judah and

the territory of Benjamin from attending the shrine at Gerizim. Eli is also held to have created a duplicate of the

Ark of the Covenant

The Ark of the Covenant,; Ge'ez: also known as the Ark of the Testimony or the Ark of God, is an alleged artifact believed to be the most sacred relic of the Israelites, which is described as a wooden chest, covered in pure gold, with an ...

, which eventually made its way to the Judahite sanctuary in Jerusalem.

A Jewish Orthodox tradition, based on material in the Bible,

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

and the

Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

, dates their presence much later, to the beginning of the Babylonian captivity. In

Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonia ...

, for example in the

Tosefta

The Tosefta ( Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: תוספתא "supplement, addition") is a compilation of the Jewish oral law from the late 2nd century, the period of the Mishnah.

Overview

In many ways, the Tosefta acts as a supplement to the Mishnah ( ...

Berakhot, the Samaritans are called ''

Cuthites

The Cuthites is a name describing a people said by the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament of Christianity) and the first century historian Josephus to be living in Samaria around 500 BCE. The name comes from the Assyrian city of Kutha, in line with the ...

'' or Cutheans ( he, כותים, ''Kutim''), referring to the ancient city of

Kutha

Kutha, Cuthah, Cuth or Cutha ( ar, كُوثَا, Sumerian: Gudua), modern Tell Ibrahim ( ar, تَلّ إِبْرَاهِيم), formerly known as Kutha Rabba ( ar, كُوثَىٰ رَبَّا), is an archaeological site in Babil Governorate, Iraq. ...

, geographically located in what is today

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

.

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

in both the ''

Wars of the Jews'' and the ''

Antiquities of the Jews

''Antiquities of the Jews'' ( la, Antiquitates Iudaicae; el, Ἰουδαϊκὴ ἀρχαιολογία, ''Ioudaikē archaiologia'') is a 20-volume historiographical work, written in Greek, by historian Flavius Josephus in the 13th year of the ...

'', in writing of the destruction of the temple on Mt. Gerizim by

John Hyrcanus 1, also refers to the Samaritans as the Cuthaeans. In the biblical account, however, Kuthah was one of several cities from which people were brought to Samaria.

The Israeli biblical scholar

Shemaryahu Talmon

Shemaryahu Talmon (Hebrew: שמריהו טלמון) (born Shemaryahu Zelmanowicz; 1920 in Skierniewice, Poland – December 15, 2010) was J. L. Magnes Professor of Bible at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, known particularly for his work in ...

has supported the Samaritan tradition that they are mainly descended from the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh who remained in Israel after the Assyrian conquest. He states that the description of them at as foreigners is tendentious and intended to ostracize the Samaritans from those Israelites who returned from the Babylonian exile in 520 BCE. He further states that could be interpreted as confirming that a large fraction of the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh (i.e., Samaritans) remained in Israel after the Assyrian exile.

Modern genetic studies support the Samaritan narrative that they descend from indigenous Israelites. Shen et al. (2004) formerly speculated that outmarriage with foreign women may have taken place. Most recently the same group came up with genetic evidence that Samaritans are closely linked to

Cohanim

Kohen ( he, , ''kōhēn'', , "priest", pl. , ''kōhănīm'', , "priests") is the Hebrew word for "priest", used in reference to the Aaronic priesthood, also called Aaronites or Aaronides. Levitical priests or ''kohanim'' are traditionally bel ...

, and therefore can be traced back to an Israelite population prior to the Assyrian invasion. This correlates with expectations from the fact that the Samaritans retained

endogamous

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting those from others as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships.

Endogamy is common in many cultu ...

and biblical

patrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritan ...

marriage customs, and that the Samaritans remained a genetically isolated population.

Samaritan version

The Samaritan traditions of their history are contained in the ''Kitab al-Ta'rikh'' compiled by

Abu'l-Fath in 1355. According to this, a text which Magnar Kartveit identifies as a "fictional"

apologia drawn from earlier sources, including

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

but perhaps also from ancient traditions, a

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

erupted among the Israelites when

Eli, son of Yafni, the treasurer of the sons of Israel, sought to usurp the

High Priesthood of Israel from the heirs of

Phinehas

According to the Hebrew Bible, Phinehas or Phineas (; , ''Phinees'', ) was a priest during the Israelites’ Exodus journey. The grandson of Aaron and son of Eleazar, the High Priests (), he distinguished himself as a youth at Shittim with h ...

. Gathering disciples and binding them by an oath of loyalty, he sacrificed on the stone altar, without using salt, a rite which made the then High Priest Ozzi rebuke and disown him. Eli and his acolytes revolted and shifted to

Shiloh, where he built an alternative Temple and an altar, a perfect replica of the original on Mt. Gerizim. Eli's sons

Hophni and Phinehas had intercourse with women and feasted on the meats of the sacrifice, inside the

Tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle ( he, מִשְׁכַּן, mīškān, residence, dwelling place), also known as the Tent of the Congregation ( he, link=no, אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד, ’ōhel mō‘ēḏ, also Tent of Meeting, etc.), ...

. Thereafter Israel was split into three factions: the original Mt. Gerizim community of loyalists, the breakaway group under Eli, and heretics worshipping idols associated with the latter's sons.

Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

emerged later with those who followed the example of Eli.

Mount Gerizim was the original Holy Place of the Israelites from the time that Joshua conquered Canaan and the tribes of Israel settled the land. The reference to Mount Gerizim derives from the biblical story of Moses ordering Joshua to take the

Twelve Tribes of Israel

The Twelve Tribes of Israel ( he, שִׁבְטֵי־יִשְׂרָאֵל, translit=Šīḇṭēy Yīsrāʾēl, lit=Tribes of Israel) are, according to Hebrew scriptures, the descendants of the biblical patriarch Jacob, also known as Israel, thro ...

to the mountains by Shechem (

Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

) and place half of the tribes, six in number, on Mount Gerizim, the Mount of the Blessing, and the other half on

Mount Ebal, the Mount of the Curse.

Biblical versions

Accounts of Samaritan origins in respectively

2 Kings 17:6,24 and

Chronicles, together with statements in both

Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe ('' sofer'') and priest ('' kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρ ...

and

Nehemiah

Nehemiah is the central figure of the Book of Nehemiah, which describes his work in rebuilding Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. He was governor of Persian Judea under Artaxerxes I of Persia (465–424 BC). The name is pronounced o ...

differ in important degrees, suppressing or highlighting narrative details according to the various intentions of their authors.

The emergence of the Samaritans as an ethnic and religious community distinct from other

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

peoples appears to have occurred at some point after the Assyrian conquest of the Israelite

Kingdom of Israel

The Kingdom of Israel may refer to any of the historical kingdoms of ancient Israel, including:

Fully independent (c. 564 years)

*Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy) (1047–931 BCE), the legendary kingdom established by the Israelites and uniting ...

in approximately 721 BCE. The records of

Sargon II

Sargon II ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is gener ...

of

Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

indicate that he deported 27,290 inhabitants of the former kingdom.

Jewish tradition affirms the Assyrian deportations and replacement of the previous inhabitants by forced resettlement by other peoples but claims a different ethnic origin for the Samaritans. The Talmud accounts for a people called

"Cuthim" on a number of occasions, mentioning their arrival by the hands of the Assyrians. According to

2 Kings 17:6, 24 and

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

, the people of Israel were removed by the king of the Assyrians (

Sargon II

Sargon II ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is gener ...

) to

Halah

Halah (; la, Hala) is a city that is mentioned in the Bible in 2 Kings 17:6 and in 1 Chronicles 5:26. It is noted when Tiglath Pileser III and later Sargon II invaded Israel, the Israelites were taken captive from Gilead and Samaria respectivel ...

, to

Gozan on the

Khabur River and to the towns of the

Medes

The Medes ( Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, ...

. The king of the Assyrians then brought people from

Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

,

Kutha

Kutha, Cuthah, Cuth or Cutha ( ar, كُوثَا, Sumerian: Gudua), modern Tell Ibrahim ( ar, تَلّ إِبْرَاهِيم), formerly known as Kutha Rabba ( ar, كُوثَىٰ رَبَّا), is an archaeological site in Babil Governorate, Iraq. ...

,

Avva

Avva (russian: А́вва) is an old and uncommon Russian male first name. Included into various, often handwritten, church calendars throughout the 17th–19th centuries, it was omitted from the official Synodal Menologium at the end of the 19 ...

,

Hama

Hama ( ar, حَمَاة ', ; syr, ܚܡܬ, ħ(ə)mɑθ, lit=fortress; Biblical Hebrew: ''Ḥamāṯ'') is a city on the banks of the Orontes River in west-central Syria. It is located north of Damascus and north of Homs. It is the provincial ...

th and

Sepharvaim to place in Samaria. Because God sent lions among them to kill them, the king of the Assyrians sent one of the priests from Bethel to teach the new settlers about God's ordinances. The eventual result was that the new settlers worshipped both the God of the land and their own gods from the countries from which they came.

In the

Chronicles, following Samaria's destruction, King

Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; hbo, , Ḥīzqīyyahū), or Ezekias); grc, Ἐζεκίας 'Ezekías; la, Ezechias; also transliterated as or ; meaning "Yahweh, Yah shall strengthen" (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the 13th king of Kingdom of Jud ...

is depicted as endeavouring to draw the

Ephraimites

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Tribe of Ephraim ( he, אֶפְרַיִם, ''ʾEp̄rayīm,'' in pausa: אֶפְרָיִם, ''ʾEp̄rāyīm'') was one of the tribes of Israel. The Tribe of Manasseh together with Ephraim formed the '' House of ...

,

Zebulonites,

Asherites and

Manassites closer to

Judah. Temple repairs at the time of

Josiah

Josiah ( or ) or Yoshiyahu; la, Iosias was the 16th king of Judah (–609 BCE) who, according to the Hebrew Bible, instituted major religious reforms by removing official worship of gods other than Yahweh. Josiah is credited by most biblical ...

were financed by money from all "the remnant of Israel" in Samaria, including from Manasseh, Ephraim, and Benjamin. Jeremiah likewise speaks of people from Shechem, Shiloh, and Samaria who brought offerings of frankincense and grain to the House of YHWH. Chronicles makes no mention of an Assyrian resettlement. Yitzakh Magen argues that the version of Chronicles is perhaps closer to the historical truth and that the Assyrian settlement was unsuccessful, a notable Israelite population remained in Samaria, part of which, following the conquest of Judah, fled south and settled there as refugees.

Adam Zertal dates the Assyrian onslaught at 721 BCE to 647 BCE, infers from a pottery type he identifies as Mesopotamian clustering around the Menasheh lands of Samaria, that they were three waves of imported settlers.

The ''

Encyclopaedia Judaica

The ''Encyclopaedia Judaica'' is a 22-volume English-language encyclopedia of the Jewish people, Judaism, and Israel. It covers diverse areas of the Jewish world and civilization, including Jewish history of all eras, culture, holidays, langu ...

'' (under "Samaritans") summarizes both past and present views on the Samaritans' origins. It says:

Furthermore, to this day the Samaritans claim descent from the tribe of Joseph.

Josephus's version

Josephus, a key source, has long been considered a prejudiced witness hostile to the Samaritans, He displays an ambiguous attitude, calling them both a distinct, opportunistic ethnos and, alternatively, a Jewish sect.

Dead Sea scrolls

The

Dead Sea scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the ...

' Proto-Esther fragment 4Q550

c has an obscure phrase about the possibility of a ''Kutha(ean)''(''Kuti'') man returning but the reference remains obscure. 4Q372 records hopes that the northern tribes will return to the land of Joseph. The current dwellers in the north are referred to as fools, an enemy people. However, they are not referred to as foreigners. It goes on to say that the Samaritans mocked Jerusalem and built a temple on a high place to provoke Israel.

History

Iron Age

The narratives in Genesis about the rivalries among the twelve sons of Jacob are viewed by some as describing tensions between north and south. According to the Hebrew Bible, they were temporarily united under a

United Monarchy, but after the death of Solomon, the kingdom split in two, the northern

Kingdom of Israel

The Kingdom of Israel may refer to any of the historical kingdoms of ancient Israel, including:

Fully independent (c. 564 years)

*Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy) (1047–931 BCE), the legendary kingdom established by the Israelites and uniting ...

with its last capital city

Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first ...

and the southern

Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah ( he, , ''Yəhūdā''; akk, 𒅀𒌑𒁕𒀀𒀀 ''Ya'údâ'' 'ia-ú-da-a-a'' arc, 𐤁𐤉𐤕𐤃𐤅𐤃 ''Bēyt Dāwīḏ'', " House of David") was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. C ...

with its capital,

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. The

Deuteronomistic history

The Deuteronomist, abbreviated as either Dtr or simply D, may refer either to the source document underlying the core chapters (12–26) of the Book of Deuteronomy, or to the broader "school" that produced all of Deuteronomy as well as the Deutero ...

, written in Judah, portrayed Israel as a sinful kingdom, divinely punished for its idolatry and iniquity by being destroyed by the

Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew ...

in 720 BCE. The tensions continued in the post-exilic period. The

Books of Kings

The Book of Kings (, '' Sēfer Məlāḵīm'') is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Kings) in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It concludes the Deuteronomistic history, a history of Israel also including the boo ...

are more inclusive than

Ezra–Nehemiah since the ideal is of one Israel with twelve tribes, whereas the

Books of Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( he, דִּבְרֵי־הַיָּמִים ) is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third sec ...

concentrate on the

Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah ( he, , ''Yəhūdā''; akk, 𒅀𒌑𒁕𒀀𒀀 ''Ya'údâ'' 'ia-ú-da-a-a'' arc, 𐤁𐤉𐤕𐤃𐤅𐤃 ''Bēyt Dāwīḏ'', " House of David") was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. C ...

and ignore the

Kingdom of Israel

The Kingdom of Israel may refer to any of the historical kingdoms of ancient Israel, including:

Fully independent (c. 564 years)

*Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy) (1047–931 BCE), the legendary kingdom established by the Israelites and uniting ...

.

Contemporary scholarship confirms that deportations did take place both before and after the Assyrian conquest of the Kingdom of Israel in 722-720 BCE. However, these deportations are thought to have been less severe than the Book of Kings portrays.

During the earlier Assyrian invasions, the

Transjordan did experience significant deportations, with entire tribes vanishing; the tribes of

Reuben

Reuben or Reuven is a Biblical male first name from Hebrew רְאוּבֵן (Re'uven), meaning "behold, a son". In the Bible, Reuben was the firstborn son of Jacob.

Variants include Rúben in European Portuguese; Rubens in Brazilian Portugu ...

,

Gad,

Dan

Dan or DAN may refer to:

People

* Dan (name), including a list of people with the name

** Dan (king), several kings of Denmark

* Dan people, an ethnic group located in West Africa

**Dan language, a Mande language spoken primarily in Côte d'Ivoir ...

, and

Naphtali

According to the Book of Genesis, Naphtali (; ) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Bilhah (Jacob's sixth son). He was the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Naphtali.

Some biblical commentators have suggested that the name ''Naphtali ...

are never again mentioned. However, Samaria was a larger and more populated area, and even if the Assyrians did deport 30,000 people as they claimed, many would have remained in the area. The cities of

Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first ...

and

Megiddo were mostly left intact, and the rural communities were generally left alone. Some scholars have claimed there's no evidence to support the settlement of foreigners in the area,

however, others disagree. Nevertheless, the

Book of Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( he, דִּבְרֵי־הַיָּמִים ) is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third se ...

records that King

Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; hbo, , Ḥīzqīyyahū), or Ezekias); grc, Ἐζεκίας 'Ezekías; la, Ezechias; also transliterated as or ; meaning "Yahweh, Yah shall strengthen" (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the 13th king of Kingdom of Jud ...

of Judah invited members of the tribes of

Ephraim

Ephraim (; he, ''ʾEp̄rayīm'', in pausa: ''ʾEp̄rāyīm'') was, according to the Book of Genesis, the second son of Joseph ben Jacob and Asenath. Asenath was an Ancient Egyptian woman whom Pharaoh gave to Joseph as wife, and the daughte ...

,

Zebulun

Zebulun (; also ''Zebulon'', ''Zabulon'', or ''Zaboules'') was, according to the Books of Genesis and Numbers,Genesis 46:14 the last of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's tenth son), and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Zebulun. Som ...

,

Asher

Asher ( he, אָשֵׁר ''’Āšēr''), in the Book of Genesis, was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Zilpah (Jacob's eighth son) and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Asher.

Name

The text of the Torah states that the name of ''As ...

,

Issachar

Issachar () was, according to the Book of Genesis, the fifth of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's ninth son), and the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Issachar. However, some Biblical scholars view this as an eponymous metaphor pro ...

and

Manasseh to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover after the destruction of Israel. In light of this, it has been suggested that the bulk of those who survived the Assyrian invasions remained in the region. The Samaritan community of today is thought to be predominantly descended from those who remained.

Samaritans claim to be descended from the

Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

of ancient Samaria who were not expelled by the Assyrian conquerors of the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE. They had their own sacred precinct on

Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim (; Samaritan Hebrew: ''ʾĀ̊rgā̊rīzēm''; Hebrew: ''Har Gərīzīm''; ar, جَبَل جَرِزِيم ''Jabal Jarizīm'' or جَبَلُ ٱلطُّورِ ''Jabal at-Ṭūr'') is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinit ...

and claimed that it was the original sanctuary. Moreover, they claimed that

their version of the Pentateuch was the original and that the Jews had a falsified text produced by

Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe ('' sofer'') and priest ('' kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρ ...

during the Babylonian exile. Both Jewish and Samaritan religious leaders taught that it was wrong to have any contact with the opposite group, and neither was to enter the other's territories or even to speak to the other. During the

New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chris ...

period, the tensions were exploited by Roman authorities as they likewise had done between rival tribal factions elsewhere, and

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

reports numerous violent confrontations between Jews and Samaritans throughout the first half of the first century.

Persian period

According to Chronicles 36:22–23, the Persian emperor,

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

(reigned 559–530 BCE), permitted the return of the exiles to their homeland and ordered the

rebuilding of the Temple (

Zion

Zion ( he, צִיּוֹן ''Ṣīyyōn'', LXX , also variously Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated ''Sion'', ''Tzion'', ''Tsion'', ''Tsiyyon'') is a placename in the Hebrew Bible used as a synonym for Jerusalem as well as for the Land of Isra ...

). The prophet Isaiah identified Cyrus as "the Lord's

Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

".

During the First Temple, it was possible for foreigners to help the Jewish people in an informal way until tension grew between the Samaritans and Judeans. This meant that foreigners could physically move into Judean land and abide by its laws and religion.

Ezra 4 says that the local inhabitants of the land offered to assist with the building of the new Temple during the time of

Zerubbabel

According to the biblical narrative, Zerubbabel, ; la, Zorobabel; Akkadian: 𒆰𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠 ''Zērubābili'' was a governor of the Achaemenid Empire's province Yehud Medinata and the grandson of Jeconiah, penultimate king of Judah. Zeru ...

, but their offer was rejected. According to Ezra, this rejection precipitated a further interference not only with the rebuilding of the Temple but also with the reconstruction of Jerusalem. The issue surrounding the Samaritans offer to help rebuild the temple was a complicated one that took a while for the Judeans to think over. There had always been a division between the north and the south and this instance perfectly illustrates that. Following Solomon's death, sectionalism formed and inevitably led to the division of the kingdom. This division led to the Judeans rejecting the offer made by the Samaritans to centralise worship at the Temple.

The text is not clear on this matter, but one possibility is that these "people of the land" were thought of as Samaritans. We do know that Samaritan and Jewish alienation increased and that the Samaritans eventually built their own temple on Mount Gerizim, near

Shechem

Shechem ( ), also spelled Sichem ( ; he, שְׁכֶם, ''Šəḵem''; ; grc, Συχέμ, Sykhém; Samaritan Hebrew: , ), was a Canaanite and Israelite city mentioned in the Amarna Letters, later appearing in the Hebrew Bible as the first c ...

.

The term "Cuthim" applied by Jews to the Samaritans had clear

pejorative

A pejorative or slur is a word or grammatical form expressing a negative or a disrespectful connotation, a low opinion, or a lack of respect toward someone or something. It is also used to express criticism, hostility, or disregard. Sometimes, a ...

connotations, and is regarded as an insult to Samaritanism, implying that they were interlopers brought in from

Kutha

Kutha, Cuthah, Cuth or Cutha ( ar, كُوثَا, Sumerian: Gudua), modern Tell Ibrahim ( ar, تَلّ إِبْرَاهِيم), formerly known as Kutha Rabba ( ar, كُوثَىٰ رَبَّا), is an archaeological site in Babil Governorate, Iraq. ...

in Mesopotamia and rejecting their claim of descent from the ancient Tribes of Israel.

The archaeological evidence can find no sign of habitation in the Assyrian and Babylonian periods at Mount Gerizim, but indicates the existence of a sacred precinct on the site in the Persian period, by the 5th century BCE. According to most modern scholars, the split between the Jews and Samaritans was a gradual historical process extending over several centuries rather than a single schism at a given point in time.

Hellenistic period

Antiochus IV Epiphanes and Hellenization

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes (; grc, Ἀντίοχος ὁ Ἐπιφανής, ''Antíochos ho Epiphanḗs'', "God Manifest"; c. 215 BC – November/December 164 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king who ruled the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his de ...

was on the throne of the

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

from 175 to 163 BCE. His policy was to

Hellenize

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the H ...

his entire kingdom and standardize religious observance. According to 1 Maccabees 1:41-50 he proclaimed himself the incarnation of the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

god

Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label= genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label= genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek relig ...

and mandated death to anyone who refused to worship him. In the 2nd century BCE, a series of events led to a revolution by a faction of Judeans against Antiochus IV.

The universal peril led the Samaritans, eager for safety, to repudiate all connection and kinship with the Jews. The request was granted. This was put forth as the final breach between the two groups. The breach was described at a much later date in the Christian Bible (John 4:9), "For Jews have no dealings with Samaritans."

Anderson notes that during the reign of Antiochus IV (175–164 BCE):

Josephus Book 12, Chapter 5 quotes the Samaritans as saying:

Destruction of the temple

During the

Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, Samaria was largely divided between a Hellenizing faction based in Samaria (

Sebastia) and a pious faction in

Shechem

Shechem ( ), also spelled Sichem ( ; he, שְׁכֶם, ''Šəḵem''; ; grc, Συχέμ, Sykhém; Samaritan Hebrew: , ), was a Canaanite and Israelite city mentioned in the Amarna Letters, later appearing in the Hebrew Bible as the first c ...

and surrounding rural areas, led by the High Priest. Samaria was a largely autonomous state nominally dependent on the

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

until around 110 BCE, when the

Hasmonean ruler

John Hyrcanus

John Hyrcanus (; ''Yōḥānān Hurqanōs''; grc, Ἰωάννης Ὑρκανός, Iōánnēs Hurkanós) was a Hasmonean ( Maccabean) leader and Jewish high priest of the 2nd century BCE (born 164 BCE, reigned from 134 BCE until his death in ...

destroyed the Samaritan temple and devastated Samaria. Only a few stone remnants of the temple exist today.

Roman period

Early Roman era

Under the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, Samaria became a part of the

Herodian Tetrarchy

The Herodian Tetrarchy was formed following the death of Herod the Great in 4 BCE, when his kingdom was divided between his sons Herod Archelaus as ethnarch, Herod Antipas and Philip as tetrarchs in inheritance, while Herod's sister Salome I ...

, and with the deposition of the Herodian

ethnarch

Ethnarch (pronounced , also ethnarches, el, ) is a term that refers generally to political leadership over a common ethnic group or homogeneous kingdom. The word is derived from the Greek words ('' ethnos'', "tribe/nation") and (''archon'', " ...

Herod Archelaus in the early 1st century CE, Samaria became a part of the province of

Judaea.

Samaritans appear briefly in the Christian gospels, most notably in the account of the

Samaritan woman at the well and the

parable of the Good Samaritan. In the former, it is noted that a substantial number of Samaritans accepted

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

through the woman's testimony to them, and Jesus stayed in Samaria for two days before returning to Cana. In the latter, it is only the Samaritan who helped the man stripped of clothing, beaten, and left on the road half dead, his Abrahamic covenantal circumcision implicitly evident. The priest and Levite walked past. But the Samaritan helped the naked man regardless of his nakedness (itself religiously offensive to the priest and Levite), his self-evident poverty, or to which Hebrew sect he belonged.

The Temple of Gerizim was rebuilt after the

Bar Kokhba revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt ( he, , links=yes, ''Mereḏ Bar Kōḵḇāʾ''), or the 'Jewish Expedition' as the Romans named it ( la, Expeditio Judaica), was a rebellion by the Jews of the Roman province of Judea, led by Simon bar Kokhba, ag ...

against the Romans, around 136 CE. A building dating to the second century BCE, the

Delos Synagogue, is commonly identified as a Samaritan synagogue, which would make it the oldest known Jewish or Samaritan synagogue.

Much of the Samaritan liturgy was set by the high priest

Baba Rabba in the 4th century.

Byzantine times

According to Samaritan sources,

Eastern Roman emperor Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

(who ruled 474–491 and whom the sources call "Zait the King of Edom") persecuted the Samaritans. The Emperor went to Neapolis (

Shechem

Shechem ( ), also spelled Sichem ( ; he, שְׁכֶם, ''Šəḵem''; ; grc, Συχέμ, Sykhém; Samaritan Hebrew: , ), was a Canaanite and Israelite city mentioned in the Amarna Letters, later appearing in the Hebrew Bible as the first c ...

), gathered the elders and asked them to convert to Christianity; when they refused, Zeno had many Samaritans killed, and re-built the synagogue as a church. Zeno then took for himself

Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim (; Samaritan Hebrew: ''ʾĀ̊rgā̊rīzēm''; Hebrew: ''Har Gərīzīm''; ar, جَبَل جَرِزِيم ''Jabal Jarizīm'' or جَبَلُ ٱلطُّورِ ''Jabal at-Ṭūr'') is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinit ...

, and built several edifices, among them a tomb for his recently deceased son, on which he put a cross, so that the Samaritans, worshiping God, would prostrate in front of the tomb. Later, in 484, the Samaritans revolted. The rebels attacked Sichem, burned five churches built on Samaritan holy places and cut the finger of bishop Terebinthus, who was officiating at the ceremony of

Pentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christian holiday which takes place on the 50th day (the seventh Sunday) after Easter Sunday. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers ...

. They elected a

Justa (or Justasa/Justasus) as their king and moved to

Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesar ...

, where a noteworthy Samaritan community lived. Here several Christians were killed and the church of St. Sebastian was destroyed. Justa celebrated the victory with games in the circus. According to the

Chronicon Paschale

''Chronicon Paschale'' (the ''Paschal'' or ''Easter Chronicle''), also called ''Chronicum Alexandrinum'', ''Constantinopolitanum'' or ''Fasti Siculi'', is the conventional name of a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. Its name com ...

, the ''dux Palaestinae'' Asclepiades, whose troops were reinforced by the Caesarea-based Arcadiani of Rheges, defeated Justa, killed him and sent his head to Zeno. According to

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

, Terebinthus went to Zeno to ask for revenge; the Emperor personally went to Samaria to quell the rebellion.

Some modern historians believe that the order of the facts preserved by Samaritan sources should be inverted, as the persecution of Zeno was a consequence of the rebellion rather than its cause, and should have happened after 484, around 489. Zeno rebuilt the church of St. Procopius in Neapolis (Sichem) and the Samaritans were banned from Mount Gerizim, on whose top a signaling tower was built to alert in case of civil unrest.

According to an anonymous biography of Mesopotamian monk named

Barsauma, whose pilgrimage to the region in the early 5th century was accompanied by clashes with locals and the forced conversion of non-Christians, Barsauma managed to convert Samaritans by conducting demonstrations of healing. Jacob, an ascetic healer living in a cave near Porphyreon,

Mount Carmel

Mount Carmel ( he, הַר הַכַּרְמֶל, Har haKarmel; ar, جبل الكرمل, Jabal al-Karmil), also known in Arabic as Mount Mar Elias ( ar, link=no, جبل مار إلياس, Jabal Mār Ilyās, lit=Mount Saint Elias/ Elijah), is a ...

in the 6th century CE, attracted admirers, including Samaritans who later converted to Christianity. Under growing government pressure, many Samaritans who refused to convert to Christianity in the sixth century may have preferred

paganism

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...

and even

Manicheism

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani (AD ...

.

Under a

charismatic

Charisma () is a personal quality of presence or charm that compels its subjects.

Scholars in sociology, political science, psychology, and management reserve the term for a type of leadership seen as extraordinary; in these fields, the term "ch ...

,

messianic figure named

Julianus ben Sabar

Julianus ben Sabar (also known as Julian or Julianus ben Sahir and Latinized as ''Iulianus Sabarides'') was a leader of the Samaritans, seen widely as being the Taheb who led a failed revolt against the Byzantine Empire during the early 6th ce ...

(or ben Sahir), the Samaritans launched a war to create their own independent state in 529. With the help of the

Ghassanids

The Ghassanids ( ar, الغساسنة, translit=al-Ġasāsina, also Banu Ghassān (, romanized as: ), also called the Jafnids, were an Arab tribe which founded a kingdom. They emigrated from southern Arabia in the early 3rd century to the Levan ...

, Emperor

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

crushed the revolt; tens of thousands of Samaritans died or were

enslaved. The Samaritan faith, which had previously enjoyed the status of ''

religio licita'', was virtually outlawed thereafter by the Christian

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

; from a population once at least in the hundreds of thousands, the Samaritan community dwindled to tens of thousands.

Middle Ages

The Samaritan community dropped in numbers during the various periods of Muslim rule in the region. The Samaritans could not rely on foreign assistance as much as the Christians did, nor on a large number of

diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

immigrants as did the Jews. The once-flourishing community declined over time, either through emigration or

conversion to Islam

Conversion to Islam is accepting Islam as a religion or faith and rejecting any other religion or irreligion. Requirements

Converting to Islam requires one to declare the '' shahādah'', the Muslim profession of faith ("there is no god but Allah ...

among those who remained.

By the time of the

Muslim conquest of the Levant

The Muslim conquest of the Levant ( ar, فَتْحُ الشَّام, translit=Feth eş-Şâm), also known as the Rashidun conquest of Syria, occurred in the first half of the 7th century, shortly after the rise of Islam."Syria." Encyclopædia Br ...

, apart from

Palestine, small dispersed communities of Samaritans were living also in

Arab Egypt,

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, and

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. Like other non-Muslims in the empire, such as Jews, Samaritans were often considered to be

People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ide ...

, and were guaranteed religious freedom. Their minority status was protected by the Muslim rulers, and they had the right to practice their religion, but, as

dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

, adult males had to pay the

jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

or "protection tax". This however changed during late Abbasid period, with increasing persecution targeting the Samaritan community and considering them infidels which must convert to Islam. The tradition of men wearing a red

tarboosh

The fez (, ), also called tarboosh ( ar, طربوش, translit=ṭarbūš, derived from fa, سرپوش, translit=sarpuš, lit=cap), is a felt headdress in the shape of a short cylindrical peakless hat, usually red, and sometimes with a black tas ...

may go back to an order by the

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

Caliph

al-Mutawakkil

Abū al-Faḍl Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad al-Muʿtaṣim bi-ʾllāh ( ar, جعفر بن محمد المعتصم بالله; March 822 – 11 December 861), better known by his regnal name Al-Mutawakkil ʿalā Allāh (, "He who relies on God") was ...

(847-861 CE) that required non-Muslims to be distinguished from Muslims.

According to Milka Levy-Rubin, many Samaritans converted under

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

and

Tulunid rule (878-905 CE), having been subjected to harsh hardships such as droughts, earthquakes, persecution by local governors, high taxes on religious minorities and anarchy.

During the

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

, the Frankish takeover of

Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

, where the majority of Samaritans lived, was relatively peaceful compared to the massacres elsewhere where one can assume that Samaritans shared the fate of Arabs and Jews generally in Palestine by being put to death or enslaved. Such acts took place in Samaritan maritime communities in

Arsuf,

Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesar ...

,

Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

and perhaps

Ascalon. During the initial

razzia in Nablus, nonetheless, the invading Franks destroyed Samaritan buildings and sometime latter tore down their

ritual bath and synagogue on Mt. Gerizim. Christians bearing crosses successfully pleaded for a calm transition. Like the non-Latin Christian inhabitants of the

Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establish ...

, came to be tolerated and perhaps favored because they were docile and had been mentioned positively in the

New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chris ...

. The calamities that befell them during the Frankish reign came from Muslims such as the commander of the Dasmascene army, Bazwȃdj, who raided Nablus in 1137 and abducted 500 Samaritan men, women and children back to Damascus.

Ottoman rule

While the majority of the Samaritan population in

Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

was massacred or converted during the reign of the Ottoman

Pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, generals, dignita ...

Mardam Beqin in the early 17th century, the remainder of the Samaritan community there, in particular, the Danafi family, which is still influential today, moved back to Nablus in the 17th century.

The Nablus community endured because most of the surviving diaspora returned, and they have maintained a tiny presence there to this day. In 1624, the last

Samaritan High Priest of the line of

Eleazar

Eleazar (; ) or Elʽazar was a priest in the Hebrew Bible, the second High Priest, succeeding his father Aaron after he died. He was a nephew of Moses.

Biblical narrative

Eleazar played a number of roles during the course of the Exodus, from cr ...

son of

Aaron

According to Abrahamic religions, Aaron ''′aharon'', ar, هارون, Hārūn, Greek (Septuagint): Ἀαρών; often called Aaron the priest ()., group="note" ( or ; ''’Ahărōn'') was a prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of ...

died without issue, but according to Samaritan tradition, descendants of Aaron's other son,

Ithamar, remained and took over the office.

By the late Ottoman period, the Samaritan community dwindled to its lowest. In the 19th century, with pressure of conversion and persecution from the local rulers and occasional natural disasters, the community fell to just over 100 persons.

British Mandate

The situation of the Samaritan community improved significantly during the

British Mandate of Palestine British Mandate of Palestine or Palestine Mandate most often refers to:

* Mandate for Palestine: a League of Nations mandate under which the British controlled an area which included Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan.

* Mandatory P ...

. At that time, they began to work in the public sector, like many other groups. The censuses of

1922

Events

January

* January 7 – Dáil Éireann (Irish Republic), Dáil Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic, ratifies the Anglo-Irish Treaty by 64–57 votes.

* January 10 – Arthur Griffith is elected President of Dáil Éirean ...

and

1931 recorded 163 and 182 Samaritans in Palestine, respectively. The majority of them lived in Nablus.

Israeli, Jordanian and Palestinian rule

After the end of the British Mandate of Palestine and the subsequent establishment of the State of Israel, some of the Samaritans who were living in

Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

emigrated to Samaria and lived in Nablus. By the late 1950s, around 100 Samaritans left the West Bank for Israel under an agreement with

the Jordanian authorities in the West Bank. In 1954,

Israeli President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi fostered a Samaritan enclave in Holon, Israel, located in 15a Ben Amram Street.

During Jordanian rule in the West Bank, Samaritans from Holon were permitted to visit Mount Gerizim only once a year, on Passover.

In 1967, Israel conquered the West Bank during the

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

, and the Samaritans there came under Israeli rule. Until the 1990s, most of the Samaritans in the West Bank resided in the West Bank city of

Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

below

Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim (; Samaritan Hebrew: ''ʾĀ̊rgā̊rīzēm''; Hebrew: ''Har Gərīzīm''; ar, جَبَل جَرِزِيم ''Jabal Jarizīm'' or جَبَلُ ٱلطُّورِ ''Jabal at-Ṭūr'') is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinit ...

. They relocated to the mountain itself near the

Israeli settlement

Israeli settlements, or Israeli colonies, are civilian communities inhabited by Israeli citizens, overwhelmingly of Jewish ethnicity, built on lands occupied by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. The international community considers Israeli se ...

of

Har Brakha as a result of violence during the

First Intifada

The First Intifada, or First Palestinian Intifada (also known simply as the intifada or intifadah),The word ''wikt:intifada, intifada'' () is an Arabic word meaning "wikt:uprising, uprising". Its strict Arabic transliteration is '. was a sus ...

(1987–1990). Consequently, all that is left of the Samaritan community in Nablus itself is an abandoned synagogue. The

Israeli army

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branch ...

maintains a presence in the area. The Samaritans of Nablus relocated to the village of

Kiryat Luza

Kiryat Luza ( ar, قرية لوزة, he, קרית לוזה) is a Samaritan village situated on Mount Gerizim near the city of Nablus in the West Bank. It is under the joint control of Israel and the Palestinian National Authority, and ...

. In the mid-1990s, the Samaritans of Kiryat Luza were granted Israeli citizenship. They also became citizens of the

Palestinian Authority

The Palestinian National Authority (PA or PNA; ar, السلطة الوطنية الفلسطينية '), commonly known as the Palestinian Authority and officially the State of Palestine, following the

Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords are a pair of agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): the Oslo I Accord, signed in Washington, D.C., in 1993; . As a result, they are the only people to possess dual Israeli-Palestinian citizenship.

Today, Samaritans in Israel are fully integrated into society and serve in the

Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

. The Samaritans of the West Bank seek good relations with their Palestinian neighbors while maintaining their Israeli citizenship, tend to be fluent in Hebrew and Arabic, and use both a Hebrew and Arab name.

Genetic studies

Demographic investigation

Demographic investigations of the Samaritan community were carried out in the 1960s. Detailed pedigrees of the last 13 generations show that the Samaritans comprise four lineages:

* The priestly

Cohen lineage from the tribe of Levi.

* The Tsedakah lineage, claiming descent from the tribe of Manasseh

* The Joshua-Marhiv lineage, claiming descent from the tribe of Ephraim

* The Danafi lineage, claiming descent from the tribe of Ephraim

Y-DNA and mtDNA comparisons

Recently several genetic studies on the Samaritan population were made using haplogroup comparisons as well as wide-genome genetic studies. Of the 12 Samaritan males used in the analysis, 10 (83%) had Y chromosomes belonging to

haplogroup J, which includes three of the four Samaritan families. The Joshua-Marhiv family belongs to

Haplogroup J-M267 (formerly "J1"), while the Danafi and Tsedakah families belong to

haplogroup J-M172

In human genetics, Haplogroup J-M172 or J2 is a Y-chromosome haplogroup which is a subclade (branch) of haplogroup J-M304. Haplogroup J-M172 is common in modern populations in Western Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, Europe, Northwestern Iran a ...

(formerly "J2"), and can be further distinguished by the M67 SNP—the derived allele of which has been found in the Danafi family—and the PF5169 SNP found in the Tsedakah family. However the biggest and most important Samaritan family, the Cohen family (Tradition: Tribe of Levi), was found to belong to

haplogroup E.

A 2004 article on the genetic ancestry of the Samaritans by Shen ''et al.'' concluded from a sample comparing Samaritans to several

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

populations, all currently living in Israel—representing the

Beta Israel

The Beta Israel ( he, בֵּיתֶא יִשְׂרָאֵל, ''Bēteʾ Yīsrāʾēl''; gez, ቤተ እስራኤል, , modern ''Bēte 'Isrā'ēl'', EAE: "Betä Ǝsraʾel", "House of Israel" or "Community of Israel"), also known as Ethiopian Jews ...

,

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

,

Iraqi Jews

The history of the Jews in Iraq ( he, יְהוּדִים בָּבְלִים, ', ; ar, اليهود العراقيون, ) is documented from the time of the Babylonian captivity c. 586 BC. Iraqi Jews constitute one of the world's oldest and mos ...

,

Libyan Jews,

Moroccan Jews