Sabaean language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sabaic, sometimes referred to as Sabaean, was a Sayhadic language that was spoken between c. 1000 BC and the 6th century AD by the

In the Late Sabaic period the ancient names of the gods are no longer mentioned and only one deity Raḥmānān is referred to. The last known inscription in Sabaic dates from 554 or 559 AD. The language's eventual extinction was brought about by the later rapid expansion of Islam, bringing with it

In the Late Sabaic period the ancient names of the gods are no longer mentioned and only one deity Raḥmānān is referred to. The last known inscription in Sabaic dates from 554 or 559 AD. The language's eventual extinction was brought about by the later rapid expansion of Islam, bringing with it

Sabaic Online Dictionary

* ttp://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Old_South_Arabian_inscriptions?uselang=de Wiki Commons: Old South Arabianbr>Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions

(Work is still in progress on Sabaic.) {{Authority control Languages attested from the 8th century BC Old South Arabian languages Extinct languages of Asia Sheba

Sabaeans

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdom that existed in Yemen from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself for much of the 1st millennium BCE. Modern historians agree th ...

. It was used as a written language by some other peoples of the ancient civilization of South Arabia

South Arabia (), or Greater Yemen, is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jazan, ...

, including the Ḥimyarites, Ḥashidites, Ṣirwāḥites, Humlanites, Ghaymānites, and Radmānites. Sabaic belongs to the South Arabian Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic language family. Sabaic is distinguished from the other members of the Sayhadic group by its use of ''h'' to mark the third person and as a causative

In linguistics, a causative (abbreviated ) is a valency-increasing operationPayne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 173–186. that indicates that a subject either ...

prefix; all of the other languages use ''s1'' in those cases. Therefore, Sabaic is called an ''h''-language and the others ''s''-languages. Numerous other Sabaic inscriptions have also been found dating back to the Sabean colonization of Africa.

Sabaic is very similar to Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

and the languages may have been mutually intelligible.

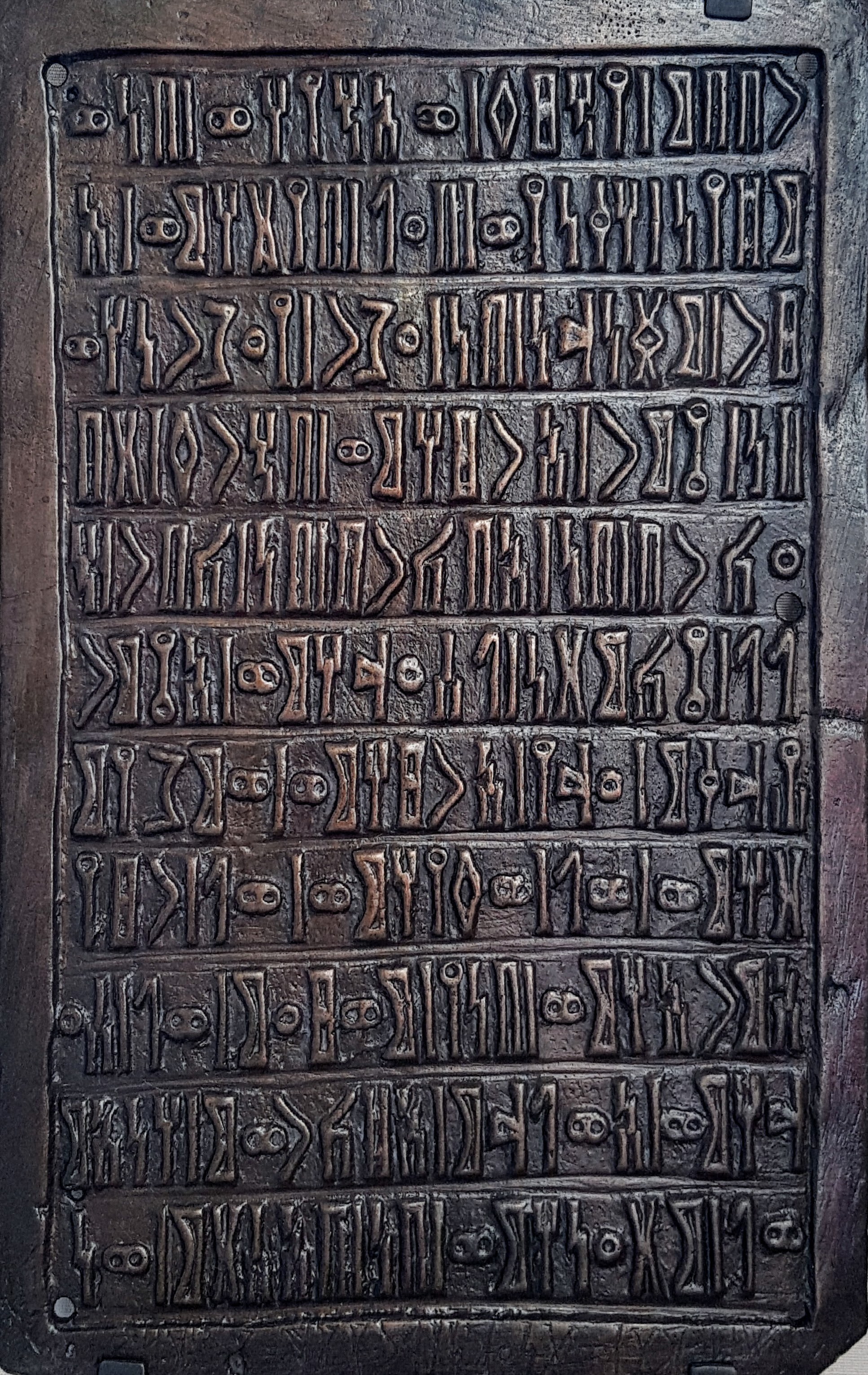

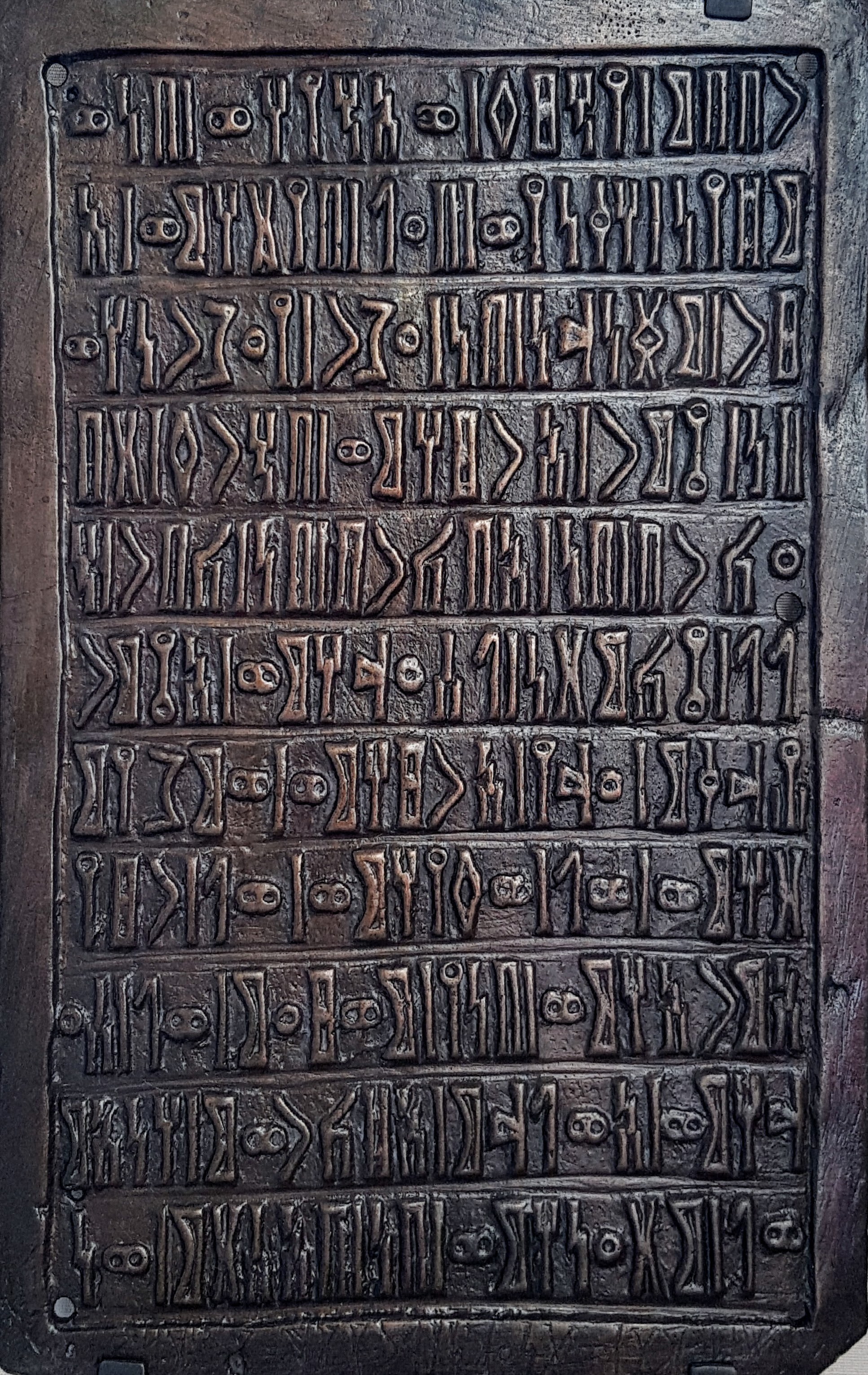

Script

Sabaic was written in theSouth Arabian alphabet

The Ancient South Arabian script (Old South Arabian: ; modern ) branched from the Proto-Sinaitic script in about the late 2nd millennium BCE, and remained in use through the late sixth century CE. It is an abjad, a writing system where only con ...

, and like Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

marked only consonants, the only indication of vowels being with matres lectionis. For many years the only texts discovered were inscriptions in the formal Masnad script (Sabaic ''ms3nd''), but in 1973 documents in another minuscule and cursive script were discovered, dating back to the second half of the 1st century BC; only a few of the latter have so far been published.

The South Arabian alphabet used in Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

, Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

, Djibouti

Djibouti, officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east. The country has an area ...

, and Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

beginning in the 8th century BC, in all three locations, later evolved into the still-in-use Geʽez script

Geʽez ( ; , ) is a script used as an abugida (alphasyllabary) for several Afroasiatic languages, Afro-Asiatic and Nilo-Saharan languages, Nilo-Saharan languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It originated as an abjad (consonantal alphabet) and was ...

. The Geʽez language however is no longer considered to be a descendant of Sabaic or of Sayhadic; and there is linguistic evidence that Semitic languages were concurrently in use, being spoken in Eritrea and Ethiopia as early as 2000 BC.

Sabaic is attested in some 1,040 dedicatory inscriptions, 850 building inscriptions, 200 legal texts, and 1300 short graffiti (containing only personal names).N. Nebes, P. Stein: Ancient South Arabian, in: Roger D. Woodard (Hrsg.): ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages''. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004 No literary texts of any length have yet been brought to light. This paucity of source material and the limited forms of the inscriptions has made it difficult to get a complete picture of Sabaic grammar. Thousands of inscriptions written in a cursive script (called ''Zabur'') incised into wooden sticks have been found and date to the Middle Sabaic period; these represent letters and legal documents and as such includes a much wider variety of grammatical forms.

Varieties

* * Sabaic: the language of the kingdom ofSaba

Saba may refer to:

Places

* Saba (island), an island of the Netherlands located in the Caribbean Sea

* Sabá, a municipality in the department of Colón, Honduras

* Șaba or Șaba-Târg, the Romanian name for Shabo, a village in Ukraine

* Saba, ...

and later also of Ḥimyar; also documented in the kingdom of Da'amot; very well documented, c. 6000 inscriptions

** Old Sabaic: mostly boustrophedon

Boustrophedon () is a style of writing in which alternate lines of writing are reversed, with letters also written in reverse, mirror-style. This is in contrast to modern European languages, where lines always begin on the same side, usually the l ...

inscriptions from the 9th until the 8th century BC and including further texts in the next two centuries from Ma'rib and the Highlands.

** Middle Sabaic: 3rd century BC until the end of the 3rd century AD. The best-documented language. The largest corpus of texts from this period comes from the Awwam Temple (otherwise known as Maḥrem Bilqīs) in Ma'rib.

*** Amiritic/Ḥaramitic: the language of the area to the north of Ma'īn

*** Central Sabaic: the language of the inscriptions from the Sabaean heartland

*** South Sabaic: the language of the inscriptions from Radmān and Ḥimyar

*** "Pseudo-Sabaic": the literary language of Arabian tribes in Najrān, Ḥaram and Qaryat al-Fāw

** Late Sabaic: 4th–6th centuries AD. This is the monotheistic period when Christianity and Judaism brought Aramaic and Greek influences.

In the Late Sabaic period the ancient names of the gods are no longer mentioned and only one deity Raḥmānān is referred to. The last known inscription in Sabaic dates from 554 or 559 AD. The language's eventual extinction was brought about by the later rapid expansion of Islam, bringing with it

In the Late Sabaic period the ancient names of the gods are no longer mentioned and only one deity Raḥmānān is referred to. The last known inscription in Sabaic dates from 554 or 559 AD. The language's eventual extinction was brought about by the later rapid expansion of Islam, bringing with it Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic () is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, e ...

(or '' Muḍarī'' Arabic), which became the language of culture and writing, totally supplanting Sabaic.

The dialect used in the western Yemeni highlands, known as Central Sabaic, is very homogeneous and generally used as the language of the inscriptions. Divergent dialects are usually found in the area surrounding the Central Highlands, such as the important dialect of the city of Ḥaram in the eastern al- Jawf. Inscriptions in the Ḥaramic dialect, which is heavily influenced by North Arabic, are also generally considered a form of Sabaic. The Himyarites, whose spoken language

A spoken language is a form of communication produced through articulate sounds or, in some cases, through manual gestures, as opposed to written language. Oral or vocal languages are those produced using the vocal tract, whereas sign languages ar ...

was Semitic but not South Arabian, used Sabaic as a written language.

Phonology

Vowels

Since Sabaic is written in anabjad

An abjad ( or abgad) is a writing system in which only consonants are represented, leaving the vowel sounds to be inferred by the reader. This contrasts with alphabets, which provide graphemes for both consonants and vowels. The term was introd ...

script leaving vowels unmarked, little can be said for certain about the vocalic system. However, based on other Semitic languages, it is generally presumed that it had at least the vowels ''a'', ''i'', and ''u'', which would have occurred both short and long ''ā'', ''ī'', and ''ū''. In Old Sabaic, the long vowels ''ū'' and ''ī'' are sometimes indicated using the letters for ''w'' and ''y'' as matres lectionis. In the Old period this is used mainly in word-final position, but in Middle and Late Sabaic it also commonly occurs medially. Sabaic has no way of writing the long vowel ''ā'', but in later inscriptions, in the Radmanite dialect the letter ''h'' is sometimes infixed in plurals where it is not etymologically expected: thus ''bnhy'' ('sons of'; constructive state) instead of the usual ''bny''; it is suspected that this ''h'' represents the vowel ''ā''. Long vowels ''ū'' and ''ī'' certainly seem to be indicated in forms such as the personal pronouns ''hmw'' ('them'), the verbal form ''ykwn'' (also written without the glide ''ykn''; 'he will be'), and in enclitic particles -''mw'', and -''my'' probably used for emphasis.

Diphthongs

In the Old Sabaic inscriptions the Proto-Semiticdiphthongs

A diphthong ( ), also known as a gliding vowel or a vowel glide, is a combination of two adjacent vowel sounds within the same syllable. Technically, a diphthong is a vowel with two different targets: that is, the tongue (and/or other parts of ...

''aw'' and ''ay'' seemed to have been retained, being written with the letters ''w'' and ''y''; in the later stages the same words are increasingly found without these letters, which leads some scholars (such as Stein) to the conclusion that they had by then contracted to ''ō'' and ''ē'' (though ''aw'' → ''ū'' and ''ay'' → ''ī'' would also be possible)

Consonants

Sabaic, likeProto-Semitic

Proto-Semitic is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Semitic languages. There is no consensus regarding the location of the linguistic homeland for Proto-Semitic: scholars hypothesize that it may have originated in the Levant, the Sahara, ...

, contains three sibilant

Sibilants (from 'hissing') are fricative and affricate consonants of higher amplitude and pitch, made by directing a stream of air with the tongue towards the teeth. Examples of sibilants are the consonants at the beginning of the English w ...

phonemes, represented by distinct letters; the exact phonetic nature of these sounds is still uncertain. In the early days of Sabaic studies, Sayhadic was transcribed using Hebrew letters. The transcriptions of the alveolars or postvelar fricatives remained controversial; after a great deal of uncertainty in the initial period the lead was taken by the transcription chosen by Nikolaus Rhodokanakis and others for the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum (''s'', ''š'', and ''ś''), until A. F. L. Beeston proposed replacing this with the representation with s followed by the subscripts 1–3. This latest version has largely taken over the English-speaking world, while in the German-speaking area, for example, the older transcription signs, which are also given in the table below, are more widespread. They were transcribed by Beeston as ''s1'', ''s2'', and ''s3''. Bearing in mind the latest reconstructions of the Proto-Semitic sibilants, we can postulate that ''s1'' was probably pronounced as a simple or � ''s2'' was probably a lateral

Lateral is a geometric term of location which may also refer to:

Biology and healthcare

* Lateral (anatomy), a term of location meaning "towards the side"

* Lateral cricoarytenoid muscle, an intrinsic muscle of the larynx

* Lateral release ( ...

fricative

A fricative is a consonant produced by forcing air through a narrow channel made by placing two articulators close together. These may be the lower lip against the upper teeth, in the case of ; the back of the tongue against the soft palate in ...

� and ''s3'' may have been realized as an affricate

An affricate is a consonant that begins as a stop and releases as a fricative, generally with the same place of articulation (most often coronal). It is often difficult to decide if a stop and fricative form a single phoneme or a consonant pai ...

͡s The difference between the three sounds is maintained throughout Old Sabaic and Middle Sabaic, but in the Late period ''s1'' and ''s3'' merge. The subscript n did not start appearing until after the Early Sabaic period. The Middle Sabaic Haramitic dialect often shows the change ''s3'' > ''s1'', for example: ''ˀks1wt'' ("clothes"), normal Sabaic ''ks3wy''.

The exact nature of the emphatic consonants ''q'', ''ṣ'', ''ṭ'', ''ẓ'' and ''ḍ'' also remains a matter for debate: were they pharyngealized as in Modern Arabic, or were they glottalized as in Ethiopic (and reconstructed Proto-Semitic)? There are arguments to support both possibilities. In any case, beginning with Middle Sabaic the letters representing ''ṣ'' and ''ẓ'' are increasingly interchanged, which seems to indicate that they have fallen together as one phoneme. The existence of bilabial fricative ''f'' as a reflex of the Proto-Semitic ''*p'' is partly proved by Latin transcriptions of names. In late Sabaic ''ḏ'' and ''z'' also merge. In Old Sabaic the sound ''n'' only occasionally assimilates to a following consonant, but in the later periods this assimilation is the norm. The minuscule ''Zabūr'' script does not seem to have a letter that represents the sound ''ẓ'', and replaces it with ''ḍ'' instead; for example ''mfḍr'' ("a measure of capacity"), written in the ''Musnad'' script as ''mfẓr''.

Sabaic consonants

Grammar

Personal pronouns

As in other Semitic languages Sabaic had both independent pronouns and pronominal suffixes. The attested pronouns, along with suffixes from Qatabanian and Hadramautic are as follows: No independent pronouns have been identified in any of the other South Arabian languages. First- and second-person independent pronouns are rarely attested in the monumental inscription, but possibly for cultural reasons; the likelihood was that these texts were neither composed nor written by the one who commissioned them: hence they use third-person pronouns to refer to the one who is paying for the building and dedication or whatever. The use of the pronouns in Sabaic corresponds to that in other Semitic languages. The pronominal suffixes are added to verbs and prepositions to denote the object; thus: ''qtl-hmw'' "he killed them"; ''ḫmr-hmy t'lb'' "Ta'lab poured for them both"; when the suffixes are added to nouns they indicate possession: bd-hw'' "his slave").The independent pronouns serve as the subject of nominal and verbal sentences: ''mr' 't'' "you are the Lord" (a nominal sentence); ''hmw f-ḥmdw'' "they thanked" (a verbal sentence).Nouns

Case, number and gender

Sayhadic nouns fall into two genders: masculine and feminine. The feminine is usually indicated in the singular by the ending –''t'' : ''bʿl'' "husband" (m.), ''bʿlt'' "wife" (f.), ''hgr'' "city" (m.), ''fnwt'' "canal" (f.). Sabaic nouns have forms for singular, dual and plural. The singular is formed without changing the stem, the plural can however be formed in a number of ways even in the very same word: * Inner ("Broken") Plurals: as in Classical Arabic they are frequent. ** ''ʾ''-Prefix

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the stem of a word. Particularly in the study of languages, a prefix is also called a preformative, because it alters the form of the word to which it is affixed.

Prefixes, like other affixes, can b ...

: ''ʾbyt'' "houses" from ''byt'' "house"

** ''t''-Suffix

In linguistics, a suffix is an affix which is placed after the stem of a word. Common examples are case endings, which indicate the grammatical case of nouns and adjectives, and verb endings, which form the conjugation of verbs. Suffixes can ca ...

: especially frequent in words having the ''m''-prefix: ''mḥfdt'' "towers" from ''mḥfd'' "tower".

** Combinations: for example ''ʾ''–prefix and ''t''-suffix: ''ʾḫrft'' "years" from ''ḫrf'' "year", ''ʾbytt'' "houses" from ''byt'' "house".

** without any external grammatical sign: ''fnw'' "canals" from ''fnwt'' (f.) "canal".

** w-/y-Infix

An infix is an affix inserted inside a word stem (an existing word or the core of a family of words). It contrasts with '' adfix,'' a rare term for an affix attached to the outside of a stem, such as a prefix or suffix.

When marking text for ...

: ''ḫrwf'' / ''ḫryf'' / ''ḫryft'' "years" from ''ḫrf'' "year".

** Reduplicational plurals are rarely attested in Sabaic: ''ʾlʾlt'' "gods" from''ʾl'' "god".

* External ("Sound") plurals: in the masculine the ending differs according to the grammatical state (see below); in the feminine the ending is -''(h)t'', which probably represents *-āt; this plural is rare and seems to be restricted to a few nouns.

The dual is already beginning to disappear in Old Sabaic; its endings vary according to the grammatical state: ''ḫrf-n'' "two years" (indeterminate state) from ''ḫrf'' "year".

Sabaic almost certainly had a case system formed by vocalic endings, but since vowels were involved they are not recognizable in the writings; nevertheless a few traces have been retained in the written texts, above all in the construct state

In Afro-Asiatic languages, the first noun in a genitive phrase that consists of a possessed noun followed by a possessor noun often takes on a special morphological form, which is termed the construct state (Latin ''status constructus''). For ex ...

.

Grammatical states

As in other Semitic languages Sabaic has a few grammatical states, which are indicated by various different endings according to the gender and the number. At the same time external plurals and duals have their own endings for grammatical state, while inner plurals are treated like singulars. Apart from theconstruct state

In Afro-Asiatic languages, the first noun in a genitive phrase that consists of a possessed noun followed by a possessor noun often takes on a special morphological form, which is termed the construct state (Latin ''status constructus''). For ex ...

known in other Semitic languages, there is also an indeterminate state and a determinate state, the functions of which are explained below. The following are the detailed state endings:

The three grammatical states have distinct syntactical and semantic functions:

* The Status indeterminatus: marks an indefinite, unspecified thing : ''ṣlm-m'' "any statue".

* The Status determinatus: marks a specific noun: ''ṣlm-n'' "the statue".

* The Status constructus: is introduced if the noun is bound to a genitive, a personal suffix or — contrary to other Semitic languages — with a relative sentence:

** With a pronominal suffix: ''ʿbd-hw'' "his slave".

** With a genitive noun: (Ḥaḑramite) ''gnʾhy myfʾt'' "both walls of Maifa'at", ''mlky s1bʾ'' "both kings of Saba"

** With a relative sentence: ''kl 1 s1bʾt 2 w-ḍbyʾ 3 w-tqdmt'' 4 s1bʾy5 w-ḍbʾ6 tqdmn7 mrʾy-hmw8 "all1 expeditions2, battles3 and raids4, their two lords 8 conducted5, struck6 and led7" (the nouns in the construct state are italicized here).

Verbs

Conjugation

As in other West Semitic languages Sabaic distinguishes between two types offinite verb

A finite verb is a verb that contextually complements a subject, which can be either explicit (like in the English indicative) or implicit (like in null subject languages or the English imperative). A finite transitive verb or a finite intra ...

forms: the perfect which is conjugated with suffixes and the imperfect which is conjugated with both prefixes and suffixes. In the imperfect two forms can be distinguished: a short form and a form constructed using the ''n'' (long form esp. the ''n-imperfect''), which in any case is missing in Qatabānian and Ḥaḍramite. In actual use it is hard to distinguish the two imperfect forms from each other. The conjugation of the perfect and imperfect may be summarized as follows (the active and the passive are not distinguished in their consonantal written form; the verbal example is ''fʿl'' "to do"):

Perfect

The perfect is mainly used to describe something that took place in the past, only before conditional phrases and in relative phrases with a conditional connotation does it describe an action in the present, as in Classical Arabic. For example: '' w-s3ḫly Hlkʾmr w-ḥmʿṯt'' "And Hlkʾmr and ḥmʿṯt have pleaded guilty (dual)".Imperfect

The imperfect usually expresses that something has occurred at the same time as an event previously mentioned, or it may simply express the present or future. Four moods can be distinguished: #Indicative

A realis mood ( abbreviated ) is a grammatical mood which is used principally to indicate that something is a statement of fact; in other words, to express what the speaker considers to be a known state of affairs, as in declarative sentence

Dec ...

: in Sabaic this has no special marker, though it has in some of the other languages: ''b-y-s2ṭ'' "he trades" (Qatabānian). With the meaning of the perfect: ''w-y-qr zydʾl b-wrḫh ḥtḥr'' "Zaid'il died in the month of Hathor

Hathor (, , , Meroitic language, Meroitic: ') was a major ancient Egyptian deities, goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky god Horus and the sun god R ...

" (Minaean).

# Precative is formed with ''l-'' and expresses wishes: ''w-l-y-ḫmrn-hw ʾlmqhw'' "may Almaqahu grant him".

# Jussive is also formed with ''l-'' and stands for an indirect order: ''l-yʾt'' "so should it come".

# Vetitive is formed with the negative ''ʾl". It serves to express negative wishes: ''w-ʾl y-hwfd ʿlbm'' "and no ʿilb-trees may be planted here“.

Imperative

The imperative is found in texts written in the ''zabūr'' script on wooden sticks, and has the form ''fˁl(-n)''. For example: ''w-'nt f-s3ḫln'' ("and you (sg.) look after").Derived stems

By changing the consonantal roots of verbs they can produce various derivational forms, which change their meaning. In Sabaic (and other Sahyadic languages) six such stems are attested. Examples: * ''qny'' "to receive" > ''hqny'' "to sacrifice; to donate" * ''qwm'' "to decree" > ''hqm'' "to decree", ''tqwmw'' "to bear witness"Syntax

Position of clauses

The arrangement of clauses is not consistent in Sabaic. The first clause in an inscription always has the order (particle - ) subject – predicate (SV), the other main clauses of an inscription are introduced by ''w''- "and" and always have – like subordinate clauses – the order predicate – subject (VS). At the same time the Predicate may be introduced by ''f''. Examples:Subordinate clauses

Sabaic is equipped with a number of means to form subordinate clauses using various conjunctions:Relative clauses

In Sabaic, relative clauses are marked by a Relativiser like ''ḏ-'', ''ʾl'', ''mn-''; in free relative clauses this marking is obligatory. Unlike other Semitic languages in Sabaic resumptive pronouns are only rarely found.Vocabulary

Although the Sabaic vocabulary is found in relatively diverse types of inscriptions (an example being that the south Semitic tribes derive their word ''wtb'' meaning "to sit" from the northwest tribe's word ''yashab/wtb'' meaning "to jump"), nevertheless it stands relatively isolated in the Semitic realm, something that makes it more difficult to analyze. Even given the existence of closely related languages such as Ge'ez and Classical Arabic, only part of the Sabaic vocabulary has proved able to be interpreted; a not inconsiderable part must be deduced from the context and some words remain incomprehensible. On the other hand, many words from agriculture and irrigation technology have been retrieved from the works of Yemeni scholars of the Middle Ages and partially also from the modern Yemeni dialects. Foreign loanwords are rare in Sabaic, a few Greek and Aramaic words are found in the Rahmanistic, Christian and Jewish period (5th–7th centuries AD) for example: ''qls1-n'' from the Greek ἐκκλησία "church", which still survives in the Arabic ''al-Qillīs'' referring to the church built by Abrahah inSana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

.The usual modern Arabic word for "church" is ''kanīsah'', from the same origin.

See also

*Old South Arabian

Ancient South Arabian (ASA; also known as Old South Arabian, Epigraphic South Arabian, Ṣayhadic, or Yemenite) is a group of four closely related extinct languages ( Sabaean/Sabaic, Qatabanic, Hadramitic, Minaic) spoken in the far southern ...

* Ancient South Arabian script

The Ancient South Arabian script (Old South Arabian: ; modern ) branched from the Proto-Sinaitic script in about the late 2nd millennium BCE, and remained in use through the late sixth century CE. It is an abjad, a writing system where only con ...

* Himyaritic language

* Geʽez

Geez ( or ; , and sometimes referred to in scholarly literature as Classical Ethiopic) is an ancient South Semitic language. The language originates from what is now Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Today, Geez is used as the main liturgical langu ...

* Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum, or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom in East Africa and South Arabia from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, based in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, and spanning present-day Djibouti and Sudan. Emerging ...

* Sabaeans

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdom that existed in Yemen from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself for much of the 1st millennium BCE. Modern historians agree th ...

* Himyarite Kingdom

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qataban, Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According ...

* Sheba

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdoms in pre-Islamic Arabia, South Arabian kingdom that existed in Yemen (region), Yemen from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself f ...

* Eduard Glaser

* Carl Rathjens

* Joseph Halévy

* Walter W. Müller

References

Bibliography

* A. F. L. Beeston: ''Sabaic Grammar'', Manchester 1984 . * A.F.L. Beeston, M.A. Ghul, W.W. Müller, J. Ryckmans: ''Sabaic Dictionary'' / Dictionnaire sabéen /al-Muʿdscham as-Sabaʾī (Englisch-Französisch-Arabisch) Louvain-la-Neuve, 1982 * Joan Copeland Biella: ''Dictionary of Old South Arabic. Sabaean dialect''. Eisenbrauns, 1982 * Maria Höfner: ''Altsüdarabische Grammatik'' (Porta linguarum Orientalium, Band 24) Leipzig, 1943 * * Anne Multhoff: ''Die sabäischen Inschriften aus Marib. Katalog, Übersetzung und Kommentar'' he Sabaean inscriptions from Marib. Catalogue, translation and commentary(Epigraphische Forschungen auf der Arabischen Halbinsel 9). Verlag Marie Leidorf, Rahden (Westfalen) 2021, . * N. Nebes, P. Stein: "Ancient South Arabian", in: Roger D. Woodard (Hrsg.): ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages'' (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004) S. 454–487 (grammatical sketch with Bibliography). * Jacques Ryckmans, Walter W. Müller, Yusuf M. Abdallah: Textes du Yémen antique inscrits sur bois exts from ancient Yemen inscribed on wood(Publications de l'Institut Orientaliste de Louvain 43). Institut Orientaliste, Louvain 1994. * Peter Stein, ''Untersuchungen zur Phonologie und Morphologie des Sabäischen'' tudies on the phonology and morphology of Sabaean(Epigraphische Forschungen auf der Arabischen Halbinsel 3). Rahden 2003, . * Peter Stein: Die altsüdarabischen Minuskelinschriften auf Holzstäbchen aus der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek in München 1: Die Inschriften der mittel- und spätsabäischen Periode he Old South Arabian minuscule inscriptions on wooden sticks from the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich 1: The inscriptions of the Middle and Late Sabaean period(Epigraphische Forschungen auf der Arabischen Halbinsel 5). Tübingen u.a. 2010. * Peter Stein: Die altsüdarabischen Minuskelinschriften auf Holzstäbchen aus der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek in München. Band 2: Die altsabäischen und minäaischen Inschriften he Old South Arabian minuscule inscriptions on wooden sticks from the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich 1: The Old Sabaean and Minaean inscriptions(Epigraphische Forschungen auf der Arabischen Halbinsel. Band 10). Wiesbaden, 2023. * Peter Stein, ''Lehrbuch der sabäischen Sprache'' abaean language textbook 2 volumes. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, (volume 1) and (volume 2).Sabaic Online Dictionary

External links

* ttp://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Old_South_Arabian_inscriptions?uselang=de Wiki Commons: Old South Arabianbr>Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions

(Work is still in progress on Sabaic.) {{Authority control Languages attested from the 8th century BC Old South Arabian languages Extinct languages of Asia Sheba