Strepsirrhines on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Strepsirrhini or Strepsirhini (; ) is a

The divergence between strepsirrhines, simians, and tarsiers likely followed almost immediately after primates first evolved. Although few fossils of

The divergence between strepsirrhines, simians, and tarsiers likely followed almost immediately after primates first evolved. Although few fossils of ] ) in Europe, North America, and Asia. They disappeared from most of the Northern Hemisphere as the climate cooled: The last of the adapiforms died out at the end of the

Adapiform primates are extinct strepsirrhines that shared many anatomical similarities with lemurs. They are sometimes referred to as lemur-like primates, although the diversity of both lemurs and adapiforms do not support this analogy.

Like the living strepsirrhines, adapiforms were extremely diverse, with at least 30 genera and 80 species known from the fossil record as of the early 2000s. They diversified across

Adapiform primates are extinct strepsirrhines that shared many anatomical similarities with lemurs. They are sometimes referred to as lemur-like primates, although the diversity of both lemurs and adapiforms do not support this analogy.

Like the living strepsirrhines, adapiforms were extremely diverse, with at least 30 genera and 80 species known from the fossil record as of the early 2000s. They diversified across

The taxonomy of strepsirrhines is controversial and has a complicated history. Confused taxonomic terminology and oversimplified anatomical comparisons have created misconceptions about primate and strepsirrhine

The taxonomy of strepsirrhines is controversial and has a complicated history. Confused taxonomic terminology and oversimplified anatomical comparisons have created misconceptions about primate and strepsirrhine

Within Strepsirrhini, two common classifications include either two infraorders (Adapiformes and Lemuriformes) or three infraorders (Adapiformes, Lemuriformes, Lorisiformes). A less common taxonomy places the aye-aye (Daubentoniidae) in its own infraorder, Chiromyiformes. In some cases, plesiadapiforms are included within the order Primates, in which case Euprimates is sometimes treated as a suborder, with Strepsirrhini becoming an infraorder, and the Lemuriformes and others become parvorders. Regardless of the infraordinal taxonomy, Strepsirrhini is composed of three ranked superfamilies and 14 families, seven of which are extinct. Three of these extinct families included the recently extinct

Within Strepsirrhini, two common classifications include either two infraorders (Adapiformes and Lemuriformes) or three infraorders (Adapiformes, Lemuriformes, Lorisiformes). A less common taxonomy places the aye-aye (Daubentoniidae) in its own infraorder, Chiromyiformes. In some cases, plesiadapiforms are included within the order Primates, in which case Euprimates is sometimes treated as a suborder, with Strepsirrhini becoming an infraorder, and the Lemuriformes and others become parvorders. Regardless of the infraordinal taxonomy, Strepsirrhini is composed of three ranked superfamilies and 14 families, seven of which are extinct. Three of these extinct families included the recently extinct

All lemuriforms possess a specialized dental structure called a "toothcomb", with the exception of the aye-aye, in which the structure has been modified into two continually growing (hypselodont)

All lemuriforms possess a specialized dental structure called a "toothcomb", with the exception of the aye-aye, in which the structure has been modified into two continually growing (hypselodont)

Strepsirrhine primates have a brain relatively comparable to or slightly larger in size than most mammals. Compared to simians, however, they have a relatively small brain-to-body size ratio. Strepsirrhines are also traditionally noted for their unfused

Strepsirrhine primates have a brain relatively comparable to or slightly larger in size than most mammals. Compared to simians, however, they have a relatively small brain-to-body size ratio. Strepsirrhines are also traditionally noted for their unfused

Approximately three-quarters of all extant strepsirrhine species are nocturnal, sleeping in nests made from dead leaves or tree hollows during the day. All of the lorisoids from continental Africa and Asia are nocturnal, a circumstance that minimizes their competition with the simian primates of the region, which are diurnal. The lemurs of Madagascar, living in the absence of simians, are more variable in their activity cycles. The aye-aye,

Approximately three-quarters of all extant strepsirrhine species are nocturnal, sleeping in nests made from dead leaves or tree hollows during the day. All of the lorisoids from continental Africa and Asia are nocturnal, a circumstance that minimizes their competition with the simian primates of the region, which are diurnal. The lemurs of Madagascar, living in the absence of simians, are more variable in their activity cycles. The aye-aye,

Like all other non-human primates, strepsirrhines face an elevated risk of extinction due to human activity, particularly deforestation in tropical regions. Much of their habitat has been converted for human use, such as agriculture and pasture. The threats facing strepsirrhine primates fall into three main categories:

Like all other non-human primates, strepsirrhines face an elevated risk of extinction due to human activity, particularly deforestation in tropical regions. Much of their habitat has been converted for human use, such as agriculture and pasture. The threats facing strepsirrhine primates fall into three main categories:

suborder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

of primate

Primates are a diverse order (biology), order of mammals. They are divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include the Tarsiiformes, tarsiers and ...

s that includes the lemuriform primates, which consist of the lemur

Lemurs ( ) (from Latin ''lemures'' – ghosts or spirits) are wet-nosed primates of the superfamily Lemuroidea (), divided into 8 families and consisting of 15 genera and around 100 existing species. They are endemic to the island of Madaga ...

s of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, galago

Galagos , also known as bush babies, or ''nagapies'' (meaning "night monkeys" in Afrikaans), are small nocturnal primates native to continental, sub-Sahara Africa, and make up the family Galagidae (also sometimes called Galagonidae). They are ...

s ("bushbabies") and potto

The pottos are three species of strepsirrhine primate in the genus ''Perodicticus'' of the family Lorisidae. In some English-speaking parts of Africa, they are called "softly-softlys".

Etymology

The common name "potto" may be from Wolof (a t ...

s from Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and the loris

Loris is the common name for the strepsirrhine mammals of the subfamily Lorinae (sometimes spelled Lorisinae) in the family Lorisidae. ''Loris'' is one genus in this subfamily and includes the slender lorises, ''Nycticebus'' is the genus con ...

es from India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

and southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

. Collectively they are referred to as strepsirrhines. Also belonging to the suborder are the extinct adapiform

Adapiformes is a group of early primates. Adapiforms radiated throughout much of the northern continental mass (now Europe, Asia and North America), reaching as far south as northern Africa and tropical Asia. They existed from the Eocene to the ...

primates which thrived during the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''ēṓs'', " ...

in Europe, North America, and Asia, but disappeared from most of the Northern Hemisphere as the climate cooled. Adapiforms are sometimes referred to as being "lemur-like", although the diversity of both lemurs and adapiforms does not support this comparison.

Strepsirrhines are defined by their "wet" (moist) rhinarium

The rhinarium (New Latin, "belonging to the nose"; plural: rhinaria) is the furless skin surface surrounding the external openings of the nostrils in many mammals. Commonly it is referred to as the tip of the ''snout'', and breeders of cats and ...

(the tip of the snout) – hence the colloquial but inaccurate term "wet-nosed" – similar to the rhinaria of canines and felines. They also have a smaller brain than comparably sized simian

The simians, anthropoids, or higher primates are an infraorder (Simiiformes ) of primates containing all animals traditionally called monkeys and apes. More precisely, they consist of the parvorders New World monkeys (Platyrrhini) and Cat ...

s, large olfactory lobes

The olfactory bulb (Latin: ''bulbus olfactorius'') is a neural structure of the vertebrate forebrain involved in olfaction, the sense of smell. It sends olfactory information to be further processed in the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex (OF ...

for smell, a vomeronasal organ

The vomeronasal organ (VNO), or Jacobson's organ, is the paired auxiliary olfactory (smell) sense organ located in the soft tissue of the nasal septum, in the nasal cavity just above the roof of the mouth (the hard palate) in various tetrapo ...

to detect pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

s, and a bicornuate uterus

A bicornuate uterus or bicornate uterus (from the Latin ''cornū'', meaning "horn"), is a type of mullerian anomaly in the human uterus, where there is a deep indentation at the fundus (top) of the uterus.

Pathophysiology

A bicornuate uterus ...

with an epitheliochorial placenta. Their eyes contain a reflective layer to improve their night vision

Night vision is the ability to see in low-light conditions, either naturally with scotopic vision or through a night-vision device. Night vision requires both sufficient spectral range and sufficient intensity range. Humans have poor night ...

, and their eye sockets

In anatomy, the orbit is the cavity or socket of the skull in which the eye and its appendages are situated. "Orbit" can refer to the bony socket, or it can also be used to imply the contents. In the adult human, the volume of the orbit is , of ...

include a ring of bone around the eye, but they lack a wall of thin bone behind it. Strepsirrhine primates produce their own vitamin C

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits and vegetables, also sold as a dietary supplement and as a topical 'serum' ingredient to treat melasma (dark pigment spots) a ...

, whereas haplorhine

Haplorhini (), the haplorhines (Greek for "simple-nosed") or the "dry-nosed" primates, is a suborder of primates containing the tarsiers and the simians (Simiiformes or anthropoids), as sister of the Strepsirrhini ("moist-nosed"). The name is som ...

primates must obtain it from their diets. Lemuriform primates are characterized by a toothcomb

A toothcomb (also tooth comb or dental comb) is a dental structure found in some mammals, comprising a group of front teeth arranged in a manner that facilitates grooming, similar to a hair comb. The toothcomb occurs in lemuriform primates ...

, a specialized set of teeth in the front, lower part of the mouth mostly used for combing fur during grooming.

Many of today's living strepsirrhines are endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inv ...

due to habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

, hunting for bushmeat

Bushmeat is meat from wildlife species that are hunted for human consumption, most often referring to the meat of game in Africa. Bushmeat represents

a primary source of animal protein and a cash-earning commodity for inhabitants of humid tro ...

, and live capture for the exotic pet

An exotic pet is a pet which is relatively rare or unusual to keep, or is generally thought of as a wild species rather than as a domesticated pet. The definition varies by culture, location, and over time—as animals become firmly enough est ...

trade. Both living and extinct strepsirrhines are behaviorally diverse, although all are primarily arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally, but others are exclusively arboreal. The habitats pose num ...

(tree-dwelling). Most living lemuriforms are nocturnal

Nocturnality is an ethology, animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnality, diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have ...

, while most adapiforms were diurnal

Diurnal ("daily") may refer to:

General

* Diurnal cycle, any pattern that recurs daily

** Diurnality, the behavior of animals and plants that are active in the daytime

* Diurnal phase shift, a phase shift of electromagnetic signals

* Diurnal tem ...

. Both living and extinct groups primarily fed on fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in partic ...

, leaves, and insects

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

.

Etymology

Thetaxonomic

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. A ...

name Strepsirrhini derives from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''strepsis'' "a turning round" and ''rhis'' "nose, snout, (in pl.) nostrils" (GEN

Gen may refer to:

* ''Gen'' (film), 2006 Turkish horror film directed by Togan Gökbakar

* Gen (Street Fighter), a video game character from the ''Street Fighter'' series

* Gen Fu, a video game character from the ''Dead or Alive'' series

* Gen l ...

''rhinos''), which refers to the appearance of the sinuous (comma-shaped) nostrils on the rhinarium

The rhinarium (New Latin, "belonging to the nose"; plural: rhinaria) is the furless skin surface surrounding the external openings of the nostrils in many mammals. Commonly it is referred to as the tip of the ''snout'', and breeders of cats and ...

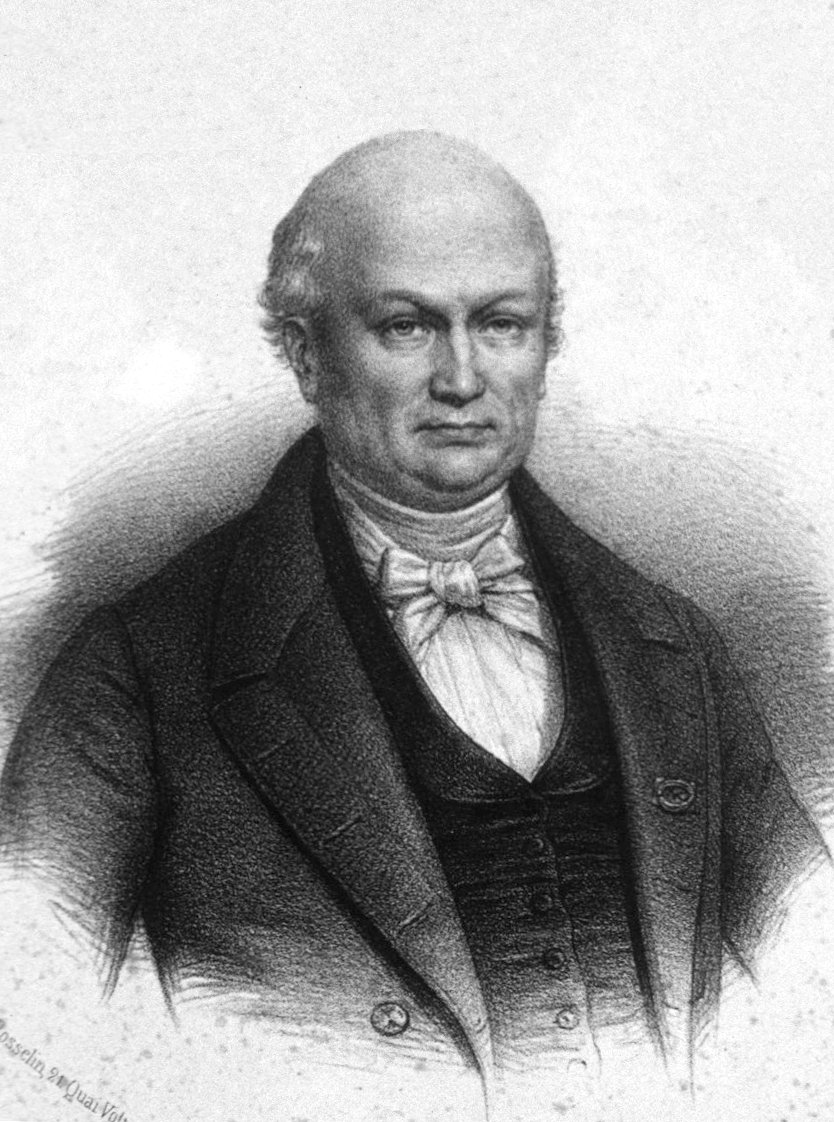

or wet nose. The name was first used by French naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theories. ...

in 1812 as a subordinal rank comparable to Platyrrhini (New World monkey

New World monkeys are the five families of primates that are found in the tropical regions of Mexico, Central and South America: Callitrichidae, Cebidae, Aotidae, Pitheciidae, and Atelidae. The five families are ranked together as the Ceboid ...

s) and Catarrhini (Old World monkey

Old World monkey is the common English name for a family of primates known taxonomically as the Cercopithecidae (). Twenty-four genera and 138 species are recognized, making it the largest primate family. Old World monkey genera include baboons ...

s). In his description

Description is the pattern of narrative development that aims to make vivid a place, object, character, or group. Description is one of four rhetorical modes (also known as ''modes of discourse''), along with exposition, argumentation, and na ...

, he mentioned "''Les narines terminales et sinueuses''" ("Nostrils terminal and winding").

When British zoologist

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

Reginald Innes Pocock

Reginald Innes Pocock F.R.S. (4 March 1863 – 9 August 1947) was a British zoologist.

Pocock was born in Clifton, Bristol, the fourth son of Rev. Nicholas Pocock and Edith Prichard. He began showing interest in natural history at St. Edwar ...

revived Strepsirrhini and defined Haplorhini

Haplorhini (), the haplorhines (Greek for "simple-nosed") or the "dry-nosed" primates, is a suborder of primates containing the tarsiers and the simians (Simiiformes or anthropoids), as sister of the Strepsirrhini ("moist-nosed"). The name is som ...

in 1918, he omitted the second "r" from both ("Strepsirhini" and "Haplorhini" instead of "Strepsirrhini" and "Haplorrhini"), although he did not remove the second "r" from Platyrrhini or Catarrhini, both of which were also named by É. Geoffroy in 1812. Following Pocock, many researchers continued to spell Strepsirrhini with a single "r" until primatologists

Primatology is the scientific study of primates. It is a diverse Academic discipline, discipline at the boundary between mammalogy and anthropology, and researchers can be found in academic departments of anatomy, anthropology, biology, medici ...

Paulina Jenkins and Prue Napier pointed out the error in 1987.

Evolutionary history

Strepsirrhines include the extinct adapiforms and the lemuriform primates, which include lemurs and lorisoids (loris

Loris is the common name for the strepsirrhine mammals of the subfamily Lorinae (sometimes spelled Lorisinae) in the family Lorisidae. ''Loris'' is one genus in this subfamily and includes the slender lorises, ''Nycticebus'' is the genus con ...

es, potto

The pottos are three species of strepsirrhine primate in the genus ''Perodicticus'' of the family Lorisidae. In some English-speaking parts of Africa, they are called "softly-softlys".

Etymology

The common name "potto" may be from Wolof (a t ...

s, and galago

Galagos , also known as bush babies, or ''nagapies'' (meaning "night monkeys" in Afrikaans), are small nocturnal primates native to continental, sub-Sahara Africa, and make up the family Galagidae (also sometimes called Galagonidae). They are ...

s). Strepsirrhines diverged from the haplorhine primates near the beginning of the primate radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, vi ...

between 55 and 90 mya. Older divergence dates are based on genetic analysis

Genetic analysis is the overall process of studying and researching in fields of science that involve genetics and molecular biology. There are a number of applications that are developed from this research, and these are also considered parts of ...

estimates, while younger dates are based on the scarce fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

. Lemuriform primates may have evolved from either cercamoniines or sivaladapids, both of which were adapiforms that may have originated in Asia. They were once thought to have evolved from adapids, a more specialized and younger branch of adapiform primarily from Europe.

Lemurs rafted from Africa to Madagascar between 47 and 54 mya, whereas the lorises split from the African galagos around 40 mya and later colonized Asia. The lemuriforms, and particularly the lemurs of Madagascar, are often portrayed inappropriately as "living fossil

A living fossil is an extant taxon that cosmetically resembles related species known only from the fossil record. To be considered a living fossil, the fossil species must be old relative to the time of origin of the extant clade. Living foss ...

s" or as examples of "basal

Basal or basilar is a term meaning ''base'', ''bottom'', or ''minimum''.

Science

* Basal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location for features associated with the base of an organism or structure

* Basal (medicine), a minimal level that is nec ...

", or "inferior" primates. These views have historically hindered the understanding of mammalian evolution

The evolution of mammals has passed through many stages since the first appearance of their synapsid ancestors in the Pennsylvanian sub-period of the late Carboniferous period. By the mid-Triassic, there were many synapsid species that looked ...

and the evolution of strepsirrhine traits, such as their reliance on smell ( olfaction), characteristics of their skeletal anatomy, and their brain size, which is relatively small. In the case of lemurs, natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

has driven this isolated population of primates to diversify significantly and fill a rich variety of ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (fo ...

s, despite their smaller and less complex brains compared to simians.

Unclear origin

The divergence between strepsirrhines, simians, and tarsiers likely followed almost immediately after primates first evolved. Although few fossils of

The divergence between strepsirrhines, simians, and tarsiers likely followed almost immediately after primates first evolved. Although few fossils of living

Living or The Living may refer to:

Common meanings

*Life, a condition that distinguishes organisms from inorganic objects and dead organisms

** Living species, one that is not extinct

*Personal life, the course of an individual human's life

* ...

primate groups – lemuriforms, tarsiers, and simians – are known from the Early to Middle Eocene, evidence from genetics and recent fossil finds both suggest they may have been present during the early adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic int ...

.

The origin of the earliest primates that the simians and tarsiers both evolved from is a mystery. Both their place of origin and the group from which they emerged are uncertain. Although the fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

demonstrating their initial radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, vi ...

across the Northern Hemisphere is very detailed, the fossil record from the tropics (where primates most likely first developed) is very sparse, particularly around the time that primates and other major clades of eutheria

Eutheria (; from Greek , 'good, right' and , 'beast'; ) is the clade consisting of all therian mammals that are more closely related to placentals than to marsupials.

Eutherians are distinguished from noneutherians by various phenotypic t ...

n mammals first appeared.

Lacking detailed tropical fossils, geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic processes ...

s and primatologists have used genetic analyses to determine the relatedness between primate lineages and the amount of time since they diverged. Using this molecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleo ...

, divergence dates for the major primate lineages have suggested that primates evolved more than 80–90 mya, nearly 40 million years before the first examples appear in the fossil record.

The early primates include both nocturnal

Nocturnality is an ethology, animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnality, diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have ...

and diurnal

Diurnal ("daily") may refer to:

General

* Diurnal cycle, any pattern that recurs daily

** Diurnality, the behavior of animals and plants that are active in the daytime

* Diurnal phase shift, a phase shift of electromagnetic signals

* Diurnal tem ...

small-bodied species, and all were arboreal, with hands and feet specially adapted for maneuvering on small branches. Plesiadapiforms

Plesiadapiformes ("Adapid-like" or "near Adapiformes") is a group of Primates, a sister of the Dermoptera. While none of the groups normally directly assigned to this group survived, the group appears actually not to be literally extinct (in th ...

from the early Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name is a combination of the Ancient Greek ''pal ...

are sometimes considered "archaic primates", because their teeth resembled those of early primates and because they possessed adaptations to living in trees, such as a divergent big toe (hallux

Toes are the digits (fingers) of the foot of a tetrapod. Animal species such as cats that walk on their toes are described as being ''digitigrade''. Humans, and other animals that walk on the soles of their feet, are described as being ''pla ...

). Although plesiadapiforms were closely related to primates, they may represent a paraphyletic

In taxonomy (general), taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's most recent common ancestor, last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few Monophyly, monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be pa ...

group from which primates may or may not have directly evolved, and some genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial ...

may have been more closely related to colugo

Colugos () are arboreal gliding mammals that are native to Southeast Asia. Their closest evolutionary relatives are primates. There are just two living species of colugos: the Sunda flying lemur (''Galeopterus variegatus'') and the Philippine f ...

s, which are thought to be more closely related to primates.

The first true primates (euprimates) do not appear in the fossil record until the early Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''ēṓs'', " ...

(~55 mya), at which point they radiated across the Northern Hemisphere during a brief period of rapid global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in a broader sense also includes ...

known as the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum

The Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum (PETM), alternatively (ETM1), and formerly known as the "Initial Eocene" or "", was a time period with a more than 5–8 °C global average temperature rise across the event. This climate event o ...

. These first primates included ''Cantius

''Cantius'' is a genus of adapiform primates from the early Eocene of North America and Europe. It is extremely well represented in the fossil record in North America and has been hypothesized to be the direct ancestor of Notharctus in North Amer ...

'', ''Donrussellia

''Donrussellia'' is a genus of adapiform primate that lived in Europe during the early Eocene. It is considered one of the earliest adapiforms, with ''D. magna'' sharing features with ''Cantius

''Cantius'' is a genus of adapiform primates ...

'', ''Altanius

''Altanius'' is a genus of extinct primates found in the early Eocene of Mongolia. Though its phylogenetic relationship is questionable, many have placed it as either a primitive omomyid or as a member of the sister group to both adapoids and o ...

'', and ''Teilhardina

''Teilhardina'' (, ) was an early marmoset-like primate that lived in Europe, North America and Asia during the Early Eocene epoch, about 56-47 million years ago. The paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson is credited with naming it after the Fr ...

'' on the northern continents, as well as the more questionable (and fragmentary) fossil ''Altiatlasius

''Altiatlasius'' ("High Atlas" from Latin altus, "high" + Atlas, "Atlas") is an extinct genus of mammal, which may have been the oldest known primate, dating to the Late Paleocene (c.57 ma) from Morocco. The only species, ''Altiatlasius koulchii ...

'' from Paleocene Africa. These earliest fossil primates are often divided into two groups, adapiforms and omomyiforms. Both appeared suddenly in the fossil record without transitional forms

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross a ...

to indicate ancestry, and both groups were rich in diversity and were widespread throughout the Eocene.

The last branch to develop were the adapiforms, a diverse and widespread group that thrived during the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''ēṓs'', " ...

(56 to 34 million years ago mya

Mya may refer to:

Brands and product names

* Mya (program), an intelligent personal assistant created by Motorola

* Mya (TV channel), an Italian Television channel

* Midwest Young Artists, a comprehensive youth music program

Codes

* Burmese ...

Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recent" ...

(~7 mya).

Adapiform evolution

Adapiform primates are extinct strepsirrhines that shared many anatomical similarities with lemurs. They are sometimes referred to as lemur-like primates, although the diversity of both lemurs and adapiforms do not support this analogy.

Like the living strepsirrhines, adapiforms were extremely diverse, with at least 30 genera and 80 species known from the fossil record as of the early 2000s. They diversified across

Adapiform primates are extinct strepsirrhines that shared many anatomical similarities with lemurs. They are sometimes referred to as lemur-like primates, although the diversity of both lemurs and adapiforms do not support this analogy.

Like the living strepsirrhines, adapiforms were extremely diverse, with at least 30 genera and 80 species known from the fossil record as of the early 2000s. They diversified across Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pan ...

during the Eocene, some reaching North America via a land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea ...

.They were among the most common mammals found in the fossil beds from that time. A few rare species have also been found in northern Africa. The most basal of the adapiforms include the genera ''Cantius'' from North America and Europe and ''Donrussellia'' from Europe. The latter bears the most ancestral traits, so it is often considered a sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

or stem group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor ...

of the other adapiforms.

Adapiforms are often divided into three major groups:

* Adapids were most commonly found in Europe, although the oldest specimens (''Adapoides

''Adapoides'' is a genus of adapiform primate dating to the Middle Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenoz ...

'' from middle Eocene China) indicate that they most likely evolved in Asia and immigrated. They died out in Europe during the Grande Coupure

Grande means "large" or "great" in many of the Romance languages. It may also refer to:

Places

*Grande, Germany, a municipality in Germany

* Grande Communications, a telecommunications firm based in Texas

* Grande-Rivière (disambiguation)

* Arr ...

, part of a significant extinction event at the end of the Eocene.

* Notharctids, which most closely resembled some of Madagascar's lemurs, come from Europe and North America. The European branch is often referred to as cercamoniines. The North American branch thrived during the Eocene, but did not survive into the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but ...

. Like the adapids, the European branch were also extinct by the end of the Eocene.

* Sivaladapids of southern and eastern Asia are best known from the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recent" ...

, and the only adapiforms to survive past the Eocene/Oligocene boundary (~34 mya). Their relationship to the other adapiforms remains unclear. They had vanished before the end of the Miocene (~7 mya).

The relationship between adapiform and lemuriform primates has not been clearly demonstrated, so the position of adapiforms as a paraphyletic stem group is questionable. Both molecular clock data and new fossil finds suggest that the lemuriform divergence from the other primates and the subsequent lemur-lorisoid split both predate the appearance of adapiforms in the early Eocene. New calibration methods may reconcile the discrepancies between the molecular clock and the fossil record, favoring more recent divergence dates. The fossil record suggests that the strepsirrhine adapiforms and the haplorhine omomyiforms had been evolving independently before the early Eocene, although their most basal members share enough dental similarities to suggest that they diverged during the Paleocene (66–55 mya).

Lemuriform evolution

Lemuriform origins are unclear and debated. Americanpaleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of foss ...

Philip Gingerich

Philip Dean Gingerich (born March 23, 1946) is a paleontologist and educator. He is Professor Emeritus of Geology, Biology, and Anthropology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He directed the Museum of Paleontology at the University ...

proposed that lemuriform primates evolved from one of several genera of European adapids based on similarities between the front lower teeth of adapids and the toothcomb

A toothcomb (also tooth comb or dental comb) is a dental structure found in some mammals, comprising a group of front teeth arranged in a manner that facilitates grooming, similar to a hair comb. The toothcomb occurs in lemuriform primates ...

of extant lemuriforms; however, this view is not strongly supported due to a lack of clear transitional fossils. Instead, lemuriforms may be descended from a very early branch of Asian cercamoniines or sivaladapids that migrated to northern Africa.

Until discoveries of three 40 million-year-old fossil lorisoids (''Karanisia

''Karanisia'' is an extinct genus of Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhine primate from middle Eocene deposits in Egypt.

Classification

Two species are known, ''K. clarki'' and ''K. arenula''. Originally considered a Crown group, crown Lorisidae, loris ...

'', '' Saharagalago'', and '' Wadilemur'') in the El Fayum deposits of Egypt between 1997 and 2005, the oldest known lemuriforms had come from the early Miocene (~20 mya) of Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

and Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The south ...

. These newer finds demonstrate that lemuriform primates were present during the middle Eocene in Afro-Arabia and that the lemuriform lineage and all other strepsirrhine taxa had diverged before then. ''Djebelemur

''Djebelemur'' is an extinct genus of early strepsirrhine primate from the late early or early middle Eocene period from the Chambi locality in Tunisia. Although they probably lacked a toothcomb, a specialized dental structure found in living ...

'' from Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

dates to the late early or early middle Eocene (52 to 46 mya) and has been considered a cercamoniine, but also may have been a stem lemuriform. Azibiids from Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, religi ...

date to roughly the same time and may be a sister group of the djebelemurid

Djebelemuridae is an extinct family of early strepsirrhine primates from Africa. It consists of five genera. The organisms in this family were exceptionally small, and were insectivores. This family dates to the early to late Eocene

The Eoce ...

s. Together with ''Plesiopithecus

''Plesiopithecus '' is an extinct genus of early strepsirrhine primate from the late Eocene.

Anatomy

Originally described from the right mandible (lower jaw), its confusing anatomy resulted in it being classified as an ape—its name tra ...

'' from the late Eocene Egypt, the three may qualify as the stem lemuriforms from Africa.

Molecular clock estimates indicate that lemurs and the lorisoids diverged in Africa during the Paleocene, approximately 62 mya. Between 47 and 54 mya, lemurs dispersed to Madagascar by rafting

Rafting and whitewater rafting are recreational outdoor activities which use an inflatable raft to navigate a river or other body of water. This is often done on whitewater or different degrees of rough water. Dealing with risk is often a ...

. In isolation, the lemurs diversified and filled the niches often filled by monkeys and apes today. In Africa, the lorises and galagos diverged during the Eocene, approximately 40 mya. Unlike the lemurs in Madagascar, they have had to compete with monkeys and apes, as well as other mammals.

History of classification

The taxonomy of strepsirrhines is controversial and has a complicated history. Confused taxonomic terminology and oversimplified anatomical comparisons have created misconceptions about primate and strepsirrhine

The taxonomy of strepsirrhines is controversial and has a complicated history. Confused taxonomic terminology and oversimplified anatomical comparisons have created misconceptions about primate and strepsirrhine phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spe ...

, illustrated by the media attention surrounding the single "Ida" fossil in 2009.

Strepsirrhine primates were first grouped under the genus ''Lemur'' by Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

in the 10th edition of ''Systema Naturae'' published in 1758. At the time, only three species were recognized, one of which (the colugo) is no longer recognized as a primate. In 1785, Dutch naturalist Pieter Boddaert

Pieter Boddaert (1730 – 6 May 1795) was a Dutch physician and naturalist.

Early life, family and education

Boddaert was the son of a Middelburg jurist and poet by the same name (1694–1760). The younger Pieter obtained his M.D. at the Univers ...

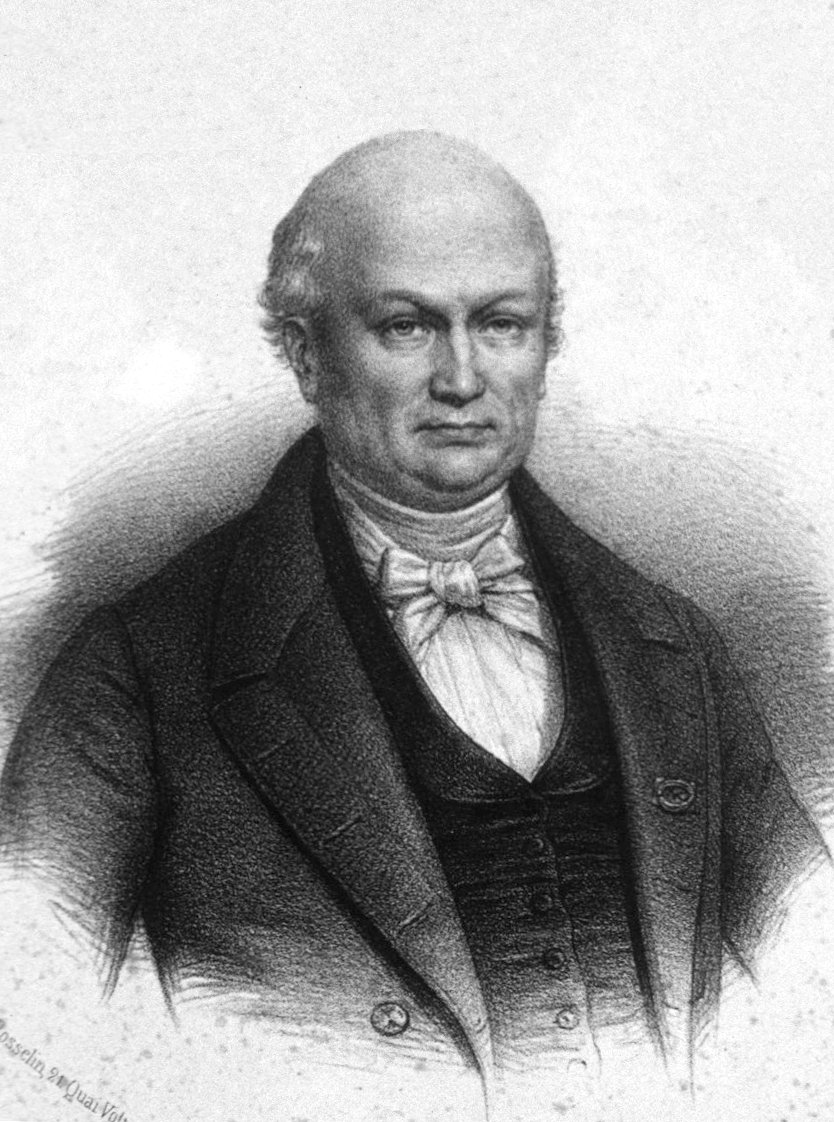

divided the genus ''Lemur'' into two genera: ''Prosimia'' for the lemurs, colugos, and tarsiers and ''Tardigradus'' for the lorises. Ten years later, É. Geoffroy and Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

grouped the tarsiers and galagos due to similarities in their hindlimb morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

, a view supported by German zoologist Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger

Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger (19 November 1775 – 10 May 1813) was a German entomologist and zoologist.

Illiger was the son of a merchant in Braunschweig. He studied under the entomologist Johann Hellwig, and later worked on the zoological colle ...

, who placed them in the family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

Macrotarsi while placing the lemurs and tarsiers in the family Prosimia (Prosimii) in 1811. The use of the tarsier-galago classification continued for many years until 1898, when Dutch zoologist Ambrosius Hubrecht

Ambrosius Arnold Willem Hubrecht (2 March 1853, in Rotterdam – 21 March 1915, in Utrecht) was a Dutch zoologist.

Hubrecht studied zoology at Utrecht University with Harting and Donders, for periods joining Selenka in Leiden and later ...

demonstrated two different types of placentation

Placentation refers to the formation, type and structure, or arrangement of the placenta. The function of placentation is to transfer nutrients, respiratory gases, and water from maternal tissue to a growing embryo, and in some instances to remov ...

(formation of a placenta

The placenta is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ (anatomy), organ that begins embryonic development, developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation (embryology), implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrien ...

) in the two groups.

English comparative anatomist

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

William Henry Flower

Sir William Henry Flower (30 November 18311 July 1899) was an English surgeon, museum curator and comparative anatomist, who became a leading authority on mammals and especially on the primate brain. He supported Thomas Henry Huxley in an im ...

created the suborder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

Lemuroidea in 1883 to distinguish these primates from the simians, which were grouped under English biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual cell, a multicellular organism, or a community of interacting populations. They usually speciali ...

St. George Jackson Mivart

St. George Jackson Mivart (30 November 1827 – 1 April 1900) was an English biologist. He is famous for starting as an ardent believer in natural selection who later became one of its fiercest critics. Mivart attempted to reconcile Da ...

's suborder Anthropoidea (=Simiiformes). According to Flower, the suborder Lemuroidea contained the families Lemuridae (lemurs, lorises, and galagos), Chiromyidae (aye-aye

The aye-aye (''Daubentonia madagascariensis'') is a long-fingered lemur, a strepsirrhine primate native to Madagascar with rodent-like teeth that perpetually grow and a special thin middle finger.

It is the world's largest nocturnal primate. ...

), and Tarsiidae (tarsiers). Lemuroidea was later replaced by Illiger's suborder Prosimii. Many years earlier, in 1812, É. Geoffroy first named the suborder Strepsirrhini, in which he included the tarsiers. This taxonomy went unnoticed until 1918, when Pocock compared the structure of the nose and reinstated the use of the suborder Strepsirrhini, while also moving the tarsiers and the simians into a new suborder, Haplorhini. It was not until 1953, when British anatomist William Charles Osman Hill

Dr William Charles Osman Hill FRSE FZS FLS FRAI (13 July 1901 – 25 January 1975) was a British anatomist, primatologist, and a leading authority on primate anatomy during the 20th century. He is best known for his nearly completed eight-vol ...

wrote an entire volume on strepsirrhine anatomy, that Pocock's taxonomic suggestion became noticed and more widely used. Since then, primate taxonomy has shifted between Strepsirrhini-Haplorhini and Prosimii-Anthropoidea multiple times.

Most of the academic literature provides a basic framework for primate taxonomy, usually including several potential taxonomic schemes. Although most experts agree upon phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spe ...

, many disagree about nearly every level of primate classification.

Controversies

The most commonly recurring debate in primatology during the 1970s, 1980s, and early 2000s concerned the phylogenetic position of tarsiers compared to both simians and the other prosimians. Tarsiers are most often placed in either the suborder Haplorhini with the simians or in the suborder Prosimii with the strepsirrhines. Prosimii is one of the two traditional primate suborders and is based onevolutionary grade

A grade is a taxon united by a level of morphological or physiological complexity. The term was coined by British biologist Julian Huxley, to contrast with clade, a strictly phylogenetic unit.

Definition

An evolutionary grade is a group of s ...

s (groups united by anatomical traits) rather than phylogenetic clades, while the Strepsirrhini-Haplorrhini taxonomy was based on evolutionary relationships. Yet both systems persist because the Prosimii-Anthropoidea taxonomy is familiar and frequently seen in the research literature and textbooks.

Strepsirrhines are traditionally characterized by several symplesiomorphic

In phylogenetics, a plesiomorphy ("near form") and symplesiomorphy are synonyms for an ancestral character shared by all members of a clade, which does not distinguish the clade from other clades.

Plesiomorphy, symplesiomorphy, apomorphy, an ...

(ancestral) traits not shared with the simians, particularly the rhinarium. Other symplesiomorphies include long snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, rostrum, or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the nose of many mammals is ...

s, convoluted maxilloturbinals, relatively large olfactory bulb

The olfactory bulb (Latin: ''bulbus olfactorius'') is a neural structure of the vertebrate forebrain involved in olfaction, the sense of smell. It sends olfactory information to be further processed in the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex (O ...

s, and smaller brains. The toothcomb is a synapomorphy

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to hav ...

(shared, derived trait) seen among lemuriforms, although it is frequently and incorrectly used to define the strepsirrhine clade. Strepsirrhine primates are also united in possessing an epitheliochorial placenta. Unlike the tarsiers and simians, strepsirrhines are capable of producing their own and do not need it supplied in their diet. Further genetic evidence for the relationship between tarsiers and simians as a haplorhine clade is the shared possession of three SINE markers.

Because of their historically mixed assemblages which included tarsiers and close relatives of primates, both Prosimii and Strepsirrhini have been considered wastebasket taxa

Wastebasket taxon (also called a wastebin taxon, dustbin taxon or catch-all taxon) is a term used by some taxonomists to refer to a taxon that has the sole purpose of classifying organisms that do not fit anywhere else. They are typically defined ...

for "lower primates". Regardless, the strepsirrhine and haplorrhine clades are generally accepted and viewed as the preferred taxonomic division. Yet tarsiers still closely resemble both strepsirrhines and simians in different ways, and since the early split between strepsirrhines, tarsiers and simians is ancient and hard to resolve, a third taxonomic arrangement with three suborders is sometimes used: Prosimii, Tarsiiformes, and Anthropoidea. More often, the term "prosimian" is no longer used in official taxonomy, but is still used to illustrate the behavioral ecology of tarsiers relative to the other primates.

In addition to the controversy over tarsiers, the debate over the origins of simians once called the strepsirrhine clade into question. Arguments for an evolutionary link between adapiforms and simians made by paleontologists Gingerich, Elwyn L. Simons

Elwyn LaVerne Simons (July 14, 1930 – March 6, 2016) was an American paleontologist, paleozoologist, and a wildlife conservationist for primates. He was known as the father of modern primate paleontology for his discovery of some of humankind' ...

, Tab Rasmussen

David Tab Rasmussen (June 17, 1958 – August 7, 2014), also known as D. Tab Rasmussen, was an American biological anthropologist. Specializing in both paleontology and behavioral ecology with interests in Paleogene mammals, early primate evoluti ...

, and others could have potentially excluded adapiforms from Strepsirrhini. In 1975, Gingerich proposed a new suborder, Simiolemuriformes, to suggest that strepsirrhines are more closely related to simians than tarsiers. However, no clear relationship between the two had been demonstrated by the early 2000s. The idea reemerged briefly in 2009 during the media attention surrounding ''Darwinius masillae

''Darwinius'' is a genus within the infraorder Adapiformes, a group of Basal (phylogenetics), basal Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhine primates from the middle Eocene geologic time scale, epoch. Its only known species, ''Darwinius masillae'', lived app ...

'' (dubbed "Ida"), a cercamoniine from Germany that was touted as a " missing link between humans and earlier primates" (simians and adapiforms). However, the cladistic analysis was flawed and the phylogenetic inferences and terminology were vague. Although the authors noted that ''Darwinius'' was not a "fossil lemur", they did emphasize the absence of a toothcomb, which adapiforms did not possess.

Infraordinal classification and clade terminology

Within Strepsirrhini, two common classifications include either two infraorders (Adapiformes and Lemuriformes) or three infraorders (Adapiformes, Lemuriformes, Lorisiformes). A less common taxonomy places the aye-aye (Daubentoniidae) in its own infraorder, Chiromyiformes. In some cases, plesiadapiforms are included within the order Primates, in which case Euprimates is sometimes treated as a suborder, with Strepsirrhini becoming an infraorder, and the Lemuriformes and others become parvorders. Regardless of the infraordinal taxonomy, Strepsirrhini is composed of three ranked superfamilies and 14 families, seven of which are extinct. Three of these extinct families included the recently extinct

Within Strepsirrhini, two common classifications include either two infraorders (Adapiformes and Lemuriformes) or three infraorders (Adapiformes, Lemuriformes, Lorisiformes). A less common taxonomy places the aye-aye (Daubentoniidae) in its own infraorder, Chiromyiformes. In some cases, plesiadapiforms are included within the order Primates, in which case Euprimates is sometimes treated as a suborder, with Strepsirrhini becoming an infraorder, and the Lemuriformes and others become parvorders. Regardless of the infraordinal taxonomy, Strepsirrhini is composed of three ranked superfamilies and 14 families, seven of which are extinct. Three of these extinct families included the recently extinct giant lemurs

Subfossil lemurs are lemurs from Madagascar that are represented by recent (subfossil) remains dating from nearly 26,000 years ago to approximately 560 years ago (from the late Pleistocene until the Holocene). They include both extant ...

of Madagascar, many of which died out within the last 1,000 years following human arrival on the island.

When Strepsirrhini is divided into two infraorders, the clade containing all toothcombed primates can be called "lemuriforms". When it is divided into three infraorders, the term "lemuriforms" refers only to Madagascar's lemurs, and the toothcombed primates are referred to as either "crown strepsirrhines" or "extant strepsirrhines". Confusion of this specific terminology with the general term "strepsirrhine", along with oversimplified anatomical comparisons and vague phylogenetic inferences, can lead to misconceptions about primate phylogeny and misunderstandings about primates from the Eocene, as seen with the media coverage of ''Darwinius''. Because the skeletons of adapiforms share strong similarities with those of lemurs and lorises, researchers have often referred to them as "primitive" strepsirrhines, lemur ancestors, or a sister group to the living strepsirrhines. They are included in Strepsirrhini, and are considered basal members of the clade. Although their status as true primates is not questioned, the questionable relationship between adapiforms and other living and fossil primates leads to multiple classifications within Strepsirrhini. Often, adapiforms are placed in their own infraorder due to anatomical differences with lemuriforms and their unclear relationship. When shared traits with lemuriforms (which may or may not be synapomorphic) are emphasized, they are sometimes reduced to families within the infraorder Lemuriformes (or superfamily Lemuroidea).

The first fossil primate described was the adapiform '' Adapis parisiensis'' by French naturalist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

in 1821, who compared it to a hyrax

Hyraxes (), also called dassies, are small, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails. Typically, they measure between long and weigh between . They are superficially simil ...

("''le Daman''"), then considered a member of a now obsolete group called pachyderms

Pachydermata (meaning 'thick skin', from the Greek grc, παχύς, pachys, thick, label=none, and grc, δέρμα, derma, skin, label=none) is an obsolete order of mammals described by Gottlieb Storr, Georges Cuvier, and others, at one time r ...

. It was not recognized as a primate until it was reevaluated in the early 1870s. Originally, adapiforms were all included under the family Adapidae, which was divided into two or three subfamilies: Adapinae, Notharctinae, and sometimes Sivaladapinae. All North American adapiforms were lumped under Notharctinae, while the Old World forms were usually assigned to Adapinae. Around the 1990s, two distinct groups of European "adapids" began to emerge, based on differences in the postcranial skeleton Postcrania (postcranium, adjective: postcranial) in zoology and vertebrate paleontology is all or part of the skeleton apart from the skull. Frequently, fossil remains, e.g. of dinosaurs or other extinct tetrapods, consist of partial or isolated sk ...

and the teeth. One of these two European forms was identified as cercamoniines, which were allied with the notharctids found mostly in North America, while the other group falls into the traditional adapid classification. The three major adapiform divisions are now typically regarded as three families within Adapiformes (Notharctidae, Adapidae and Sivaladapidae), but other divisions ranging from one to five families are used as well.

Anatomy and physiology

Grooming apparatus

All lemuriforms possess a specialized dental structure called a "toothcomb", with the exception of the aye-aye, in which the structure has been modified into two continually growing (hypselodont)

All lemuriforms possess a specialized dental structure called a "toothcomb", with the exception of the aye-aye, in which the structure has been modified into two continually growing (hypselodont) incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, w ...

s (or canine teeth

In mammalian oral anatomy, the canine teeth, also called cuspids, dog teeth, or (in the context of the upper jaw) fangs, eye teeth, vampire teeth, or vampire fangs, are the relatively long, pointed teeth. They can appear more flattened however ...

), similar to those of rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are roden ...

s. Often, the toothcomb is incorrectly used to characterize all strepsirrhines. Instead, it is unique to lemuriforms and is not seen among adapiforms.

Lemuriforms groom orally, and also possess a grooming claw

A grooming claw (or toilet claw) is the specialized claw or nail on the foot of certain primates, used for personal grooming. All prosimians have a grooming claw, but the digit that is specialized in this manner varies. Tarsiers have a groom ...

on the second toe of each foot for scratching in areas that are inaccessible to the mouth and tongue. It is unclear whether adapiforms possessed grooming claws. The toothcomb consists of either two or four procumbent

This page provides a glossary of plant morphology. Botanists and other biologists who study plant morphology use a number of different terms to classify and identify plant organs and parts that can be observed using no more than a handheld magni ...

lower incisors and procumbent lower canine teeth followed by a canine-shaped premolar

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

. It is used to comb the fur during oral grooming. Shed hairs that accumulate between the teeth of the toothcomb are removed by the sublingua

The sublingua ("under-tongue") is a muscular secondary tongue found below the primary tongue in tarsiers and living strepsirrhine primates, which includes lemurs and lorisoids (collectively called " lemuriforms"). Although it is most fully devel ...

or "under-tongue". Lemuriforms also possess a grooming claw

A grooming claw (or toilet claw) is the specialized claw or nail on the foot of certain primates, used for personal grooming. All prosimians have a grooming claw, but the digit that is specialized in this manner varies. Tarsiers have a groom ...

on the second digit of each foot for scratching. Adapiforms did not possess a toothcomb. Instead, their lower incisors varied in orientation – from somewhat procumbent to somewhat vertical – and the lower canines were projected upwards and were often prominent. Adapiforms may have had a grooming claw, but there is little evidence of this.

Eyes

Like all primates, strepsirrhine orbits (eye sockets) have apostorbital bar The postorbital bar (or postorbital bone) is a bony arched structure that connects the frontal bone of the skull to the zygomatic arch, which runs laterally around the eye socket. It is a trait that only occurs in mammalian taxa, such as most strep ...

, a protective ring of bone created by a connection between the frontal

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* ''The Front'', 1976 film

Music

*The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and ea ...

and zygomatic bone

In the human skull, the zygomatic bone (from grc, ζῠγόν, zugón, yoke), also called cheekbone or malar bone, is a paired irregular bone which articulates with the maxilla, the temporal bone, the sphenoid bone and the frontal bone. It is ...

s. Both living and extinct strepsirrhines lack a thin wall of bone behind the eye, referred to as postorbital closure, which is only seen in haplorhine primates. Although the eyes of strepsirrhines point forward, giving stereoscopic vision

Stereopsis () is the component of depth perception retrieved through binocular vision.

Stereopsis is not the only contributor to depth perception, but it is a major one. Binocular vision happens because each eye receives a different image beca ...

, the orbits do not face fully forward. Among living strepsirrhines, most or all species are thought to possess a reflective layer behind the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

of the eye, called a tapetum lucidum

The ''tapetum lucidum'' ( ; ; ) is a layer of tissue in the eye of many vertebrates and some other animals. Lying immediately behind the retina, it is a retroreflector. It reflects visible light back through the retina, increasing the light av ...

(consisting of riboflavin

Riboflavin, also known as vitamin B2, is a vitamin found in food and sold as a dietary supplement. It is essential to the formation of two major coenzymes, flavin mononucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide. These coenzymes are involved in e ...

crystals), which improves vision in low light, but they lack a fovea

Fovea () (Latin for "pit"; plural foveae ) is a term in anatomy. It refers to a pit or depression in a structure.

Human anatomy

* Fovea centralis of the retina

* Fovea buccalis or Dimple

* Fovea of the femoral head

*Trochlear fovea of the f ...

, which improves day vision. This differs from tarsiers, which lack a tapetum lucidum but possess a fovea.

Skull

Strepsirrhine primates have a brain relatively comparable to or slightly larger in size than most mammals. Compared to simians, however, they have a relatively small brain-to-body size ratio. Strepsirrhines are also traditionally noted for their unfused

Strepsirrhine primates have a brain relatively comparable to or slightly larger in size than most mammals. Compared to simians, however, they have a relatively small brain-to-body size ratio. Strepsirrhines are also traditionally noted for their unfused mandibular symphysis

In human anatomy, the facial skeleton of the skull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more p ...

(two halves of the lower jaw), however, fusion of the mandibular symphysis was common in adapiforms, notably ''Notharctus''. Also, several extinct giant lemurs exhibited a fused mandibular symphysis.

Ears

Many nocturnal species have large, independently movable ears, although there are significant differences in sizes and shapes of the ear between species. The structure of themiddle

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek (d ...

and inner ear

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance. In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in t ...

of strepsirrhines differs between the lemurs and lorisoids. In lemurs, the tympanic cavity

The tympanic cavity is a small cavity surrounding the bones of the middle ear. Within it sit the ossicles, three small bones that transmit vibrations used in the detection of sound.

Structure

On its lateral surface, it abuts the external auditor ...

, which surrounds the middle ear, is expanded. This leaves the ectotympanic ring The ectotympanic, or tympanicum, is a bony structure found in all mammals, located on the tympanic part of the temporal bone, which holds the tympanic membrane (eardrum) in place. In catarrhine primates (including humans), it takes a tube-shape. ...

, which supports the eardrum

In the anatomy of humans and various other tetrapods, the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane or myringa, is a thin, cone-shaped membrane that separates the external ear from the middle ear. Its function is to transmit sound from the air ...

, free within the auditory bulla

The tympanic part of the temporal bone is a curved plate of bone lying below the squamous part of the temporal bone, in front of the mastoid process, and surrounding the external part of the ear canal.

It originates as a separate bone (tympani ...

. This trait is also seen in adapiforms. In lorisoids, however, the tympanic cavity is smaller and the ectotympanic ring becomes attached to the edge of the auditory bulla. The tympanic cavity in lorisoids also has two accessory air spaces, which are not present in lemurs.

Neck arteries

Both lorisoids andcheirogaleid

The Cheirogaleidae are the family of strepsirrhine primates containing the various dwarf and mouse lemurs. Like all other lemurs, cheirogaleids live exclusively on the island of Madagascar.

Characteristics

Cheirogaleids are smaller than the othe ...

lemurs have replaced the internal carotid artery with an enlarged ascending pharyngeal artery

The ascending pharyngeal artery is an artery in the neck that supplies the pharynx, developing from the proximal part of the embryonic second aortic arch.

It is the smallest branch of the external carotid and is a long, slender vessel, deeply se ...

.

Ankle bones

Strepsirrhines also possess distinctive features in theirtarsus

Tarsus may refer to:

Biology

*Tarsus (skeleton), a cluster of articulating bones in each foot

*Tarsus (eyelids), elongated plate of dense connective tissue in each eyelid

*The distal segment of an arthropod leg see Arthropod tarsus

*The lower le ...

(ankle bones) that differentiate them from haplorhines, such as a sloping talo-fibular facet (the face where the talus bone

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known as the tarsus. The tarsus forms the lower part of the ankle joint. It transmits the entire weight of the body from the ...

and fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a human leg, leg bone on the Lateral (anatomy), lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long ...

meet) and a difference in the location of the position of the flexor fibularis tendon on the talus. These differences give strepsirrhines the ability to make more complex rotations of the ankle and indicate that their feet are habitually inverted, or turned inward, an adaptation for grasping vertical supports.

Sex characteristics

Sexual dichromatism (different coloration patterns between males and females) can be seen in most brown lemur species, but otherwise lemurs show very little if any difference in body size or weight between sexes. This lack ofsexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

is not characteristic of all strepsirrhines. Some adapiforms were sexually dimorphic, with males bearing a larger sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are exceptiona ...

(a ridge of bone on the top of the skull to which jaw muscles attach) and canine teeth. Lorisoids exhibit some sexual dimorphism, but males are typically no more than 20 percent larger than females.

Rhinarium and olfaction

Strepsirrhines have a long snout that ends in a moist and touch-sensitiverhinarium

The rhinarium (New Latin, "belonging to the nose"; plural: rhinaria) is the furless skin surface surrounding the external openings of the nostrils in many mammals. Commonly it is referred to as the tip of the ''snout'', and breeders of cats and ...

, similar to that of dogs and many other mammals. The rhinarium is surrounded by vibrissae

Vibrissae (; singular: vibrissa; ), more generally called Whiskers, are a type of stiff, functional hair used by mammals to sense their environment. These hairs are finely specialised for this purpose, whereas other types of hair are coarse ...

that are also sensitive to touch. Convoluted maxilloturbinals on the inside of their nose filter, warm, and moisten the incoming air, while olfactory receptor

Olfactory receptors (ORs), also known as odorant receptors, are chemoreceptors expressed in the cell membranes of olfactory receptor neurons and are responsible for the detection of odorants (for example, compounds that have an odor) which give ri ...

s of the main olfactory system

The olfactory system, or sense of smell, is the sensory system used for smelling (olfaction). Olfaction is one of the special senses, that have directly associated specific organs. Most mammals and reptiles have a main olfactory system and an ...

lining the ethmoturbinals detect airborne smells. The olfactory bulbs of lemurs are comparable in size to those of other arboreal mammals.

The surface of the rhinarium does not have any olfactory receptors, so it is not used for smell in terms of detecting volatile

Volatility or volatile may refer to:

Chemistry

* Volatility (chemistry), a measuring tendency of a substance or liquid to vaporize easily

* Relative volatility, a measure of vapor pressures of the components in a liquid mixture

* Volatiles, a gr ...

substances. Instead, it has sensitive touch receptors (Merkel cell

Merkel cells, also known as Merkel-Ranvier cells or tactile epithelial cells, are oval-shaped mechanoreceptors essential for light touch sensation and found in the skin of vertebrates. They are abundant in highly sensitive skin like that of the f ...

s). The rhinarium, upper lip, and gums are tightly connected by a fold of mucous membrane

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It i ...

called the philtrum

The philtrum ( la, philtrum from Ancient Greek ''phíltron,'' lit. "love charm"), or medial cleft, is a vertical indentation in the middle area of the upper lip, common to therian mammals, extending in humans from the nasal septum to the tuber ...