straight-tusked elephant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The straight-tusked elephant (''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'') is an extinct species of

The body, including the pelvis, of ''P. antiquus'' was broad relative to extant

The body, including the pelvis, of ''P. antiquus'' was broad relative to extant

The species was

The species was

The straight-tusked elephant (''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'') in Pleistocene Europe

Doctoral thesis (Ph.D), UCL (University College London).40 The straight-tusked elephant was scientifically named in 1847 by British palaeontologists

During the late 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century, ''Palaeoloxodon'' species were thought to share a close common ancestry with Asian elephants and other species of ''Elephas'', which was based on a number of morphological similarities between the two groups. In 2016, a

During the late 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century, ''Palaeoloxodon'' species were thought to share a close common ancestry with Asian elephants and other species of ''Elephas'', which was based on a number of morphological similarities between the two groups. In 2016, a

''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' is known from abundant finds across Europe, reaching its widest distribution on the continent during warm

''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' is known from abundant finds across Europe, reaching its widest distribution on the continent during warm

During interglacial periods, ''P. antiquus'' existed as part of the ''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' large-mammal assemblage, along with other temperate adapted

During interglacial periods, ''P. antiquus'' existed as part of the ''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' large-mammal assemblage, along with other temperate adapted

At the Lehringen site in north Germany, dating to the Eemian/Last Interglacial (around 130–115,000 years ago) a skeleton of a mature adult ''P. antiquus'', around 45 years of age, was found with a complete (though currently fractured) spear/lance between its ribs, with flint artifacts found close by, providing unequivocal evidence that this specimen was hunted,H. Thieme, S. Veil, Neue Untersuchungen zum eemzeitlichen Elefanten-Jagdplatz Lehringen, Ldkr. Verden. ''Kunde'' 36, 11–58 (1985). though it has been suggested the elephant may have already been mired prior to being killed. The spear/lance, which is around long, is made of yew wood, specifically of the species ''

At the Lehringen site in north Germany, dating to the Eemian/Last Interglacial (around 130–115,000 years ago) a skeleton of a mature adult ''P. antiquus'', around 45 years of age, was found with a complete (though currently fractured) spear/lance between its ribs, with flint artifacts found close by, providing unequivocal evidence that this specimen was hunted,H. Thieme, S. Veil, Neue Untersuchungen zum eemzeitlichen Elefanten-Jagdplatz Lehringen, Ldkr. Verden. ''Kunde'' 36, 11–58 (1985). though it has been suggested the elephant may have already been mired prior to being killed. The spear/lance, which is around long, is made of yew wood, specifically of the species ''

Yew wood, would you? An exploration of the selection of wood for Pleistocene spears

'' In: Berihuete-Azorin, M., Martin Seijo, M., Lopez-Bulto, O. and Pique, R. (eds.) The Missing Woodland Resources: Archaeobotanical studies of the use of plant raw materials. Advances in Archaeobotany, 6 (6). Barkhuis Publishing, Groningen, pp. 5-22. The Lehringen spear/lance is one of the oldest known wooden weapons after the Clacton spearhead (also made of yew wood) and the

elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

that inhabited Europe and Western Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

during the Middle and Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as the Upper Pleistocene from a Stratigraphy, stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division ...

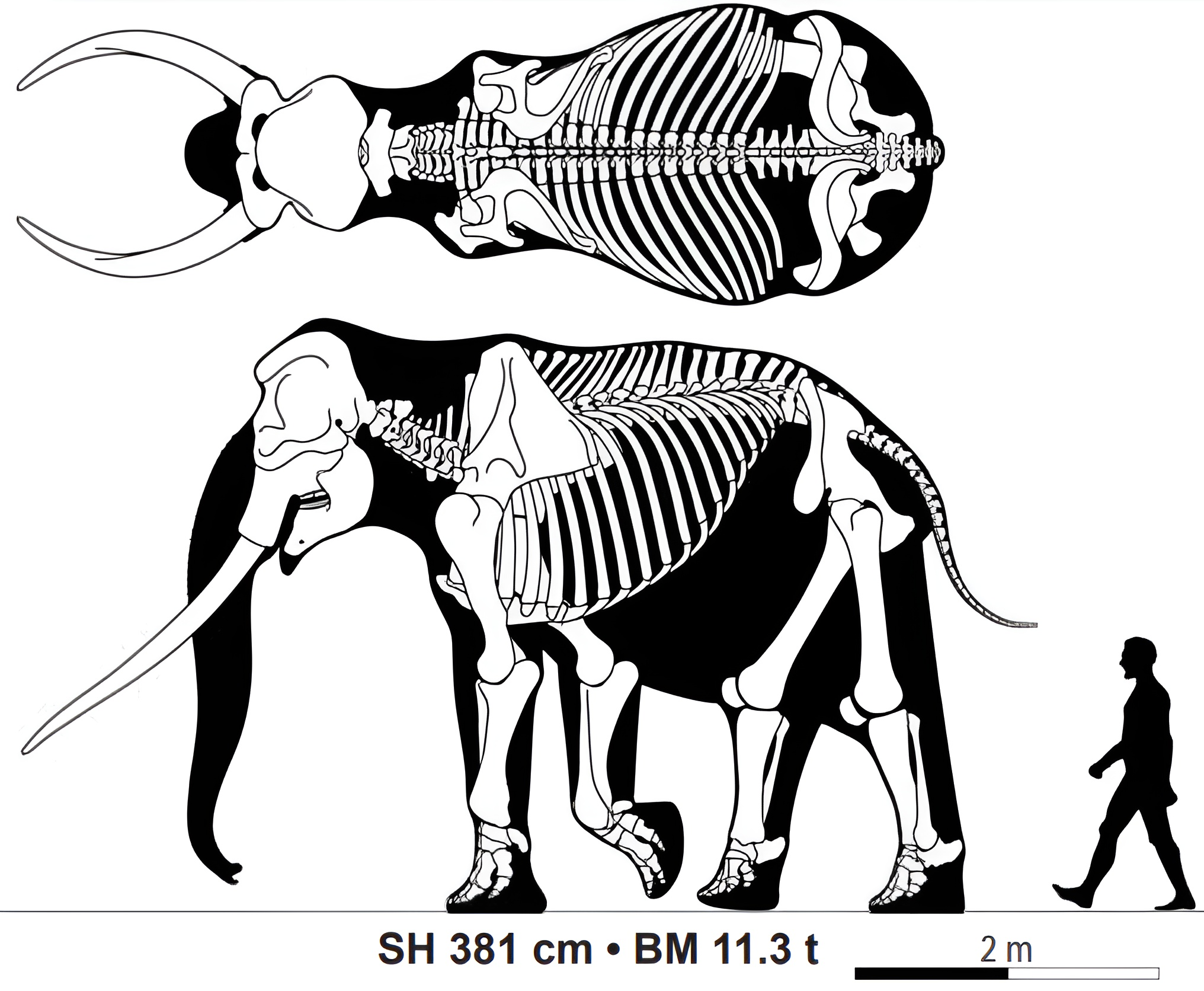

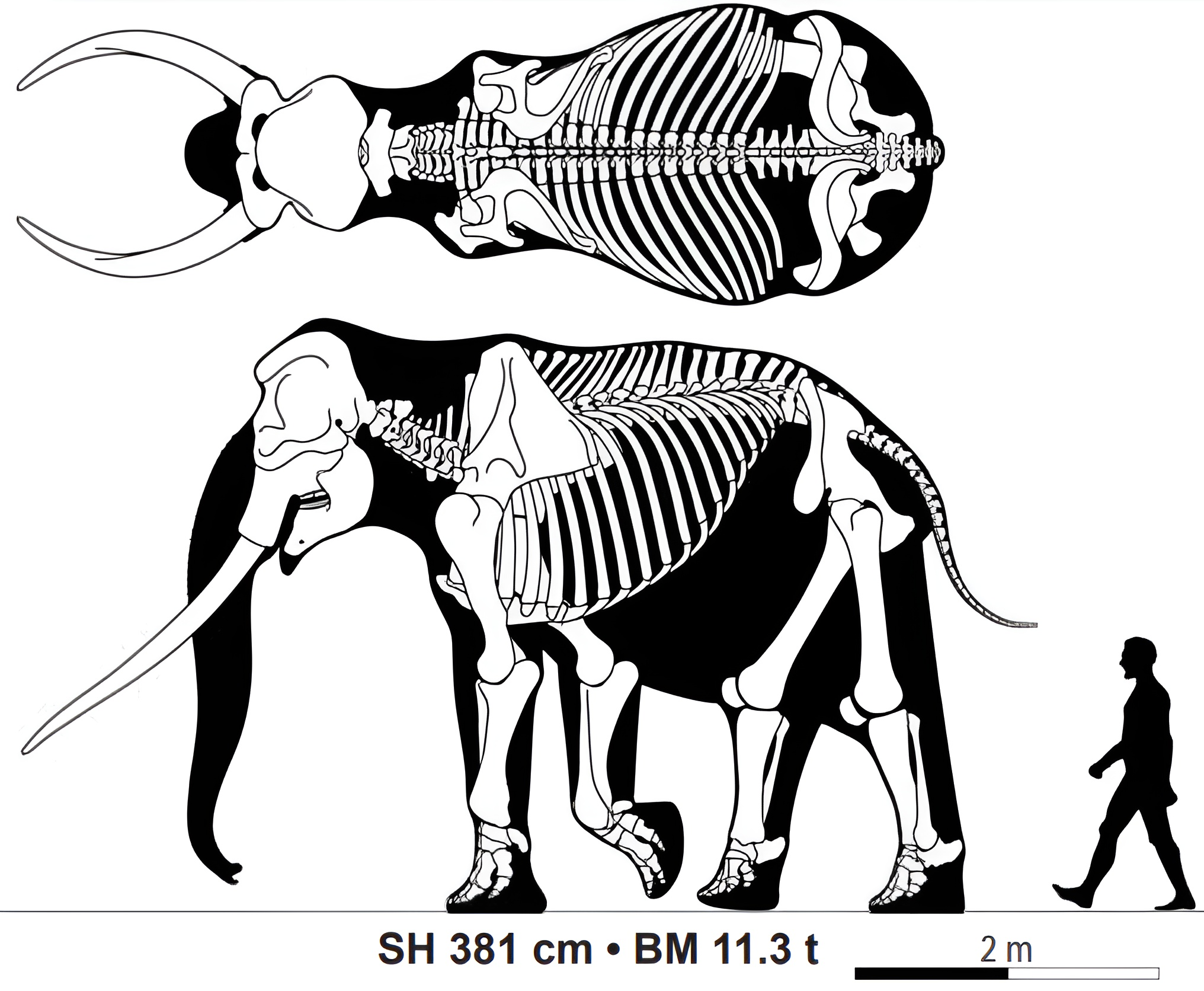

. One of the largest known elephant species, mature fully grown bulls on average had a shoulder height of and a weight of . Straight-tusked elephants likely lived very similarly to modern elephants, with herds of adult females and juveniles and solitary adult males. The species was primarily associated with temperate and Mediterranean woodland and forest habitats, flourishing during interglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene i ...

periods, when its range would extend across Europe as far north as Great Britain and Denmark and eastwards into Russia, while persisting in southern Europe during glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

s, when northern Europe was occupied by steppe mammoths and later woolly mammoths. Skeletons found in association with stone tools and in one case, a wooden spear, suggest they were scavenged and hunted by early humans, including ''Homo heidelbergensis

''Homo heidelbergensis'' is a species of archaic human from the Middle Pleistocene of Europe and Africa, as well as potentially Asia depending on the taxonomic convention used. The species-level classification of ''Homo'' during the Middle Pleis ...

'' and their Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

successors.

The species is part of the genus ''Palaeoloxodon

''Palaeoloxodon'' is an extinct genus of elephant. The genus originated in Africa during the Early Pleistocene, and expanded into Eurasia at the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene. The genus contains the largest known species of elephants, with ...

'' (whose other members are also sometimes called straight-tusked elephants), which emerged in Africa during the Early Pleistocene

The Early Pleistocene is an unofficial epoch (geology), sub-epoch in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, representing the earliest division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently esti ...

, before dispersing across Eurasia at the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene, with the earliest record of ''Palaeoloxodon'' in Europe dated to around 800–700,000 years ago, around the time of the extinction of the previously dominant mammoth species ''Mammuthus meridionalis

''Mammuthus meridionalis'', sometimes called the southern mammoth, is an extinct species of mammoth native to Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene. Reaching a size exceeding modern elephants, unlike later Eurasian mammoth species, it was largely ...

''. The straight-tusked elephant is the ancestor of over half a dozen named (and several more unnamed) species of dwarf elephant

Dwarf elephants are prehistoric members of the order Proboscidea which, through the process of allopatric speciation on islands, evolved much smaller body sizes (around shoulder height) in comparison with their immediate ancestors. Dwarf elephant ...

s that inhabited islands in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

. The species became extinct during the latter half of the Last Glacial Period, with the youngest remains found in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, dating to around 44,000 years ago. Possible even younger records include a single tooth from the Netherlands that has been dated to around 37,000 years ago, and footprints from the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula dated to 28,000 years ago.

Description

Anatomy

The body, including the pelvis, of ''P. antiquus'' was broad relative to extant

The body, including the pelvis, of ''P. antiquus'' was broad relative to extant elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

s. The forelimbs, particularly the humerus, and the scapula are proportionally longer than those of living elephants, resulting in a high position of the shoulder. The head represents the highest point of the animal, with the back being somewhat sloped though irregular in shape. The spines of the back vertebrae are noticeably elongate. The tail was relatively long. Although not preserved, the body was probably only sparsely covered in hair, similar to extant elephants, and probably had relatively large ears.

The skull is proportionally both very wide and tall. Like many other members of the genus ''Palaeoloxodon

''Palaeoloxodon'' is an extinct genus of elephant. The genus originated in Africa during the Early Pleistocene, and expanded into Eurasia at the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene. The genus contains the largest known species of elephants, with ...

'', ''P. antiquus'' possesses a well-developed growth of bone at the top of the cranium above the nasal opening called the parieto-occipital crest, originating from the occipital bone

The occipital bone () is a neurocranium, cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lob ...

of the skull roof which projects forwards and overhangs the rest of the skull. The crest was probably an anchor for muscles, including the splenius

The splenius muscles are:

*Splenius capitis muscle

*Splenius cervicis muscle

Their origins are in the upper thoracic and lower cervical spinous process

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bo ...

, as well as an additional muscle layer that wrapped around the top of the head, called the "extra splenius". The latter was likely similar to the "splenius superficialis" found in Asian elephant

The Asian elephant (''Elephas maximus''), also known as the Asiatic elephant, is the only living ''Elephas'' species. It is the largest living land animal in Asia and the second largest living Elephantidae, elephantid in the world. It is char ...

s. The crest likely developed to support the very large size of the head, as the skulls of ''Palaeoloxodon'' are the largest proportionally and in absolute size among proboscideans. Two morphs of ''P. antiquus'' were previously thought to exist in Europe on the basis of differences in the parieto-occipital crest, one more similar to the South Asian '' Palaeoloxodon namadicus''. These differences were shown to be age-related (ontogenetic

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the stu ...

variation), with the crest being more pronounced in older individuals, as well as due to distortion during fossilisation ( taphonomic variation). ''P. antiquus'' differs from ''P. namadicus'' in having a less stout cranium and more robust limb bones, and in lacking a teardrop-shaped indentation behind the eye socket (infraorbital depression). The premaxillary bones (which contain the tusks) are fan-shaped and very broad in front view. The tusks are very long relative to the size of the body and vary from straight to slightly curved. The teeth are high crowned (hypsodont

Hypsodont is a pattern of dentition characterized by with high crowns, providing extra material for wear and tear. Some examples of animals with hypsodont dentition are cows and horses; all animals that feed on gritty, fibrous material. The oppos ...

), with each third molar having approximately 16–21 lamellae (ridges).

Size

sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, with males being substantially larger than females; this size dimorphism was more pronounced than in living elephants. ''P. antiquus'' was on average considerably larger than any living elephant, and among the largest known land mammals to have ever lived. Under optimal conditions where individuals were capable of reaching full growth potential, 90% of mature fully grown straight-tusked elephant bulls are estimated to have had shoulder heights in the region of and a weight between . For comparison, 90% of mature fully grown bulls of the largest living elephant species, the African bush elephant

The African bush elephant (''Loxodonta africana''), also known as the African savanna elephant, is a species of elephant native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is one of three extant elephant species and, along with the African forest elephant, one ...

under optimal growth conditions have heights between and masses between . Extremely large bulls, such as those represented by a now lost pelvis and tibia collected from the Iberian Peninsula (including the San Isidro del Campo site in Spain) in the 19th century, may have reached shoulder heights of and body masses of over . Adult males had tusks typically around long, with masses comfortably exceeding . The preserved portion of one particularly large and thick tusk from Aniene, Italy, is in length, has a circumference of around where it would have exited the skull, and is estimated to have weighed over in life.

Females were considerably larger than living female elephants and comparable in size with African bush elephant bulls, with female individuals from the Neumark Nord population in Germany reaching shoulder heights and weights rarely exceeding and respectively (though several relatively young females at the site would likely have exceeded this size when fully grown). A particularly large female known from a pelvis found near Binsfeld in Germany has been estimated to have had a shoulder height of and a weight of . For comparison, 90% of fully grown female African bush elephants reach an shoulder height of and body mass of under optimal growth conditions. Newborn and young calves were likely around the same size as those of modern elephants. A largely complete 5 year old calf from Cova del Rinoceront in Spain was estimated to have a shoulder height of and a body mass of , which is comparable to a similarly aged African bush elephant.

History of discovery, taxonomy and evolution

Early finds and research history

In the second century AD, the Greek geographer Pausanias remarked that theMegalopolis

A megalopolis () or a supercity, also called a megaregion, is a group of metropolitan areas which are perceived as a continuous urban area through common systems of transport, economy, resources, ecology, and so on. They are integrated enough ...

region in the central part of the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

peninsula in southern Greece was known for its enormous bones, which Pausanias reported were considered to be those of giants

A giant is a being of human appearance, sometimes of prodigious size and strength, common in folklore.

Giant(s) or The Giant(s) may also refer to:

Mythology and religion

*Giants (Greek mythology)

* Jötunn, a Germanic term often translated as 'g ...

who died during the Gigantomachy

In Greek and Roman mythology, the Giants, also called Gigantes (Greek: Γίγαντες, '' Gígantes'', Γίγας, '' Gígas''), were a race of great strength and aggression, though not necessarily of great size. They were known for the Gigant ...

, a mythic climactic battle between the giants and the Greek gods. Given that this region is today known for its straight-tusked elephant fossils, it is plausible that at least some of the giant bones to which Pausanias referred were those of straight-tusked elephants.

In 1695, remains of a straight-tusked elephant were collected from travertine

Travertine ( ) is a form of terrestrial limestone deposited around mineral springs, especially hot springs. It often has a fibrous or concentric appearance and exists in white, tan, cream-colored, and rusty varieties. It is formed by a process ...

deposits near Burgtonna in what is now Thuringia

Thuringia (; officially the Free State of Thuringia, ) is one of Germany, Germany's 16 States of Germany, states. With 2.1 million people, it is 12th-largest by population, and with 16,171 square kilometers, it is 11th-largest in area.

Er ...

, Germany. While these remains were originally declared to be purely mineral in nature by the ''Collegium Medicum'' in the nearby city of Gotha

Gotha () is the fifth-largest city in Thuringia, Germany, west of Erfurt and east of Eisenach with a population of 44,000. The city is the capital of the district of Gotha and was also a residence of the Ernestine Wettins from 1640 until the ...

, Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel, a polymath in the employ of the ducal court of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg

Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg () was a duchy ruled by the Ernestine branch of the House of Wettin in today's Thuringia, Germany. The extinction of the line in 1825 led to a major re-organisation of the Thuringian states.

History

In 1640 the sons of the ...

, correctly identified them as elephant remains. The Burgtonna skeleton was one of the specimens that Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He has be ...

described in his publication naming the woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived from the Middle Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with the African ...

(''Mammuthus primigenius'', originally ''Elephas primigenius'') in 1799. The remains of straight-tusked elephants continued to be attributed to woolly mammoths until the 1840s.Davies, Paul; (2002The straight-tusked elephant (''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'') in Pleistocene Europe

Doctoral thesis (Ph.D), UCL (University College London).40 The straight-tusked elephant was scientifically named in 1847 by British palaeontologists

Hugh Falconer

Hugh Falconer MD FRS (29 February 1808 – 31 January 1865) was a Scottish geologist, botanist, palaeontologist, and paleoanthropologist. He studied the flora, fauna, and geology of India, Assam, Burma, and most of the Mediterranean island ...

and Proby Cautley as ''Elephas'' (''Euelephas'') ''antiquus''.40-41 The type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wikt:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to ancho ...

is a mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

(lower jaw) with a second molar (M2006). The exact provenance of the specimen is unknown, though it probably originates from Britain, and possibly the site of Grays in Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, southeast England. This specimen was originally considered to be that of a mammoth, and the attribution to ''E. antiquus'' was made in a hand-written correction.40 The common name "straight-tusked elephant" was used for the species as early as 1873 by William Boyd Dawkins. In 1924, the Japanese paleontologist Matsumoto Hikoshichirō assigned ''E. antiquus'' to his new taxon ''Palaeoloxodon

''Palaeoloxodon'' is an extinct genus of elephant. The genus originated in Africa during the Early Pleistocene, and expanded into Eurasia at the beginning of the Middle Pleistocene. The genus contains the largest known species of elephants, with ...

'', which he classified as a subgenus of '' Loxodonta'' (which includes the living African elephants).40 The species has a confused taxonomic history, with at least 21 named synonyms

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

.41 In publications in the 1930s and 1940s (the latter published posthumously), Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was professor of anatomy at Columbia University, president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 y ...

assigned the species to its own genus ''Hesperoloxodon,'' which was followed by some later authors, but is now rejected.42 In his widely cited 1973 work, ''Origin and evolution of the Elephantidae'', Vincent J. Maglio sunk ''P. antiquus'' into the South Asian ''P. namadicus'', as well as ''Palaeoloxodon'' back into ''Elephas

''Elephas'' is a genus of elephants and one of two surviving genera in the Family (biology), family Elephantidae, comprising one extant species, the Asian elephant (''E. maximus''). Several extinct species have been identified as belonging to t ...

'' (which contains the living Asian elephant

The Asian elephant (''Elephas maximus''), also known as the Asiatic elephant, is the only living ''Elephas'' species. It is the largest living land animal in Asia and the second largest living Elephantidae, elephantid in the world. It is char ...

). While the sinking of ''Palaeoloxodon'' into ''Elephas'' (with ''Palaeoloxodon'' sometimes being treated as a subgenus

In biology, a subgenus ( subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the ge ...

of ''Elephas'') gained considerable traction in the following decades, today both ''P. antiquus'' and ''Palaeoloxodon'' are considered distinct.

DNA analysis

mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

sequence analysis instead found that the mitochondrial genome of ''P. antiquus'' was nested within those of the African forest elephant

The African forest elephant (''Loxodonta cyclotis'') is one of the two living species of African elephant, along with the African bush elephant. It is native to humid tropical forests in West Africa and the Congo Basin. It is the smallest of the ...

(''Loxodonta cyclotis''), with analysis of a partial nuclear genome supporting a closer relationship to ''L. cyclotis'' than to the African bush elephant (''L. africana''). A subsequent study published in 2018 that includes some of the same authors presented a complete nuclear genome sequence, indicating a more complicated relationship between straight-tusked elephants and other species of elephants. According to this study, the lineage of ''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' was the result of reticulate evolution

Reticulate evolution, or network evolution is the origination of a lineage through the partial merging of two ancestor lineages, leading to relationships better described by a phylogenetic network than a bifurcating tree. Reticulate patterns can ...

, with the majority of the genome of straight-tusked elephants deriving from a lineage of elephants that was most closely related but basal to the common ancestor of forest and bush elephants (~60% of total genomic contribution), which had significant introgressed ancestry from African forest elephants (>33%) and to a lesser extent from mammoths

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

(~5%). The African forest elephant ancestry was more closely related to modern West African forest elephants than to other African forest elephant populations. This hybridisation likely occurred in Africa, prior to migration of ''Palaeoloxodon'' into Eurasia, and appears to be shared with other ''Palaeoloxodon'' species.

Evolution

Like other Eurasian ''Palaeoloxodon'' species'', P. antiquus'' is believed to derive from the migration of a population of '' Palaeoloxodon recki'' out of Africa, suggested to have occurred around 800,000 years ago, approximately at the boundary between theEarly Pleistocene

The Early Pleistocene is an unofficial epoch (geology), sub-epoch in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, representing the earliest division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently esti ...

and Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, more widely known as the Middle Pleistocene (its previous informal name), is an Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale or a Stage (stratigraphy), stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocen ...

. ''P. antiquus'' first appeared during the Middle Pleistocene, with the earliest record of ''Palaeoloxodon'' in Europe being from the Slivia site in Italy, dating to around 800–700,000 years ago. Its earliest known appearance in northern Europe is in England around 600,000 years ago. The arrival of ''Palaeoloxodon'' in Europe coincided with the extinction of the temperate-adapted European mammoth species ''Mammuthus meridionalis

''Mammuthus meridionalis'', sometimes called the southern mammoth, is an extinct species of mammoth native to Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene. Reaching a size exceeding modern elephants, unlike later Eurasian mammoth species, it was largely ...

'' and the migration of ''Mammuthus trogontherii

''Mammuthus trogontherii'', sometimes called the steppe mammoth, is an extinct species of mammoth that ranged over most of northern Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene, Early and Middle Pleistocene, approximately 1.7 million to 200,000 years ag ...

'' (the steppe mammoth) into Europe from Asia. The arrival of ''Palaeoloxodon'' in Europe was part of a larger faunal turnover event around the transition between the Early and Middle Pleistocene, where many European mammal species that characterised the preceding late Villafranchian became extinct, along with the dispersal of immigrant species into Europe from Asia and Africa.

There appears to be no overlap between ''M. meridionalis'' and ''P. antiquus'', which suggests that the latter might have outcompeted the former. During ''P. antiquus''dwarf elephant

Dwarf elephants are prehistoric members of the order Proboscidea which, through the process of allopatric speciation on islands, evolved much smaller body sizes (around shoulder height) in comparison with their immediate ancestors. Dwarf elephant ...

s that are thought to have evolved from the straight-tusked elephant are known from many Mediterranean islands, spanning from Sicily and Malta in the west to Cyprus in the east. The responsible factors for the dwarfing of animals on islands are thought to include the reduction in food availability, predation and competition from other herbivores.

Distribution and habitat

''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' is known from abundant finds across Europe, reaching its widest distribution on the continent during warm

''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' is known from abundant finds across Europe, reaching its widest distribution on the continent during warm interglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene i ...

periods. Fossils are also known from Israel, western Iran and probably Turkey in West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

. Some remains of the species have also been reported from Central Asia in northeastern Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

and Tajikistan

Tajikistan, officially the Republic of Tajikistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Dushanbe is the capital city, capital and most populous city. Tajikistan borders Afghanistan to the Afghanistan–Tajikistan border, south, Uzbekistan to ...

. Outside of Eastern Europe, the northernmost records of the species are known from Great Britain, Denmark and Poland, around the 55th parallel north. Some of the northernmost reported fossils of the species are from the banks of the Kolva river in the Russian Urals at around the 60th parallel north

The 60th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 60 degrees north of Earth's equator. It crosses Europe, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

Although it lies approximately twice as far away from the Equator as ...

. During glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

s ''P. antiquus'' permanently resided in the Mediterranean region. Many of the West Asian remains have been assigned to the species primarily on the basis of geography, and it has been suggested that some of these, such as those from Israel, actually belong to ''P. recki''. A 2004 study attributed the holotype of ''Palaeoloxodon turkmenicus

''Palaeoloxodon turkmenicus'' is an extinct species of elephant belonging to the genus ''Palaeoloxodon,'' known from the Middle Pleistocene of Central Asia and South Asia.

Taxonomy

The species was described in 1955 based on a partial adult sku ...

,'' a skull found in western Turkmenistan, to ''P. antiquus'', but later analysis found that ''P. turkmenicus'' represented a morphologically distinct and valid species. During the 2020s, some authors began to suggest that ''Palaeoloxodon'' remains from China (otherwise assigned to, among others, the species '' Palaeoloxodon huaihoensis'') may represent ''P. antiquus''. The straight-tusked elephant is primarily associated with temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ran ...

and Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

forest and woodland habitats, as opposed to the colder open steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without closed forests except near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the tropical and subtropica ...

environments inhabited by contemporary mammoths, though the species is also known to have inhabited open grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominance (ecology), dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes such as clover, and other Herbaceo ...

s, and is thought to have been tolerant of a range of environmental conditions.

Behaviour and paleoecology

As with modern elephants, female and juvenile straight-tusked elephants are thought to have lived inmatriarchal

Matriarchy is a social system in which positions of power and privilege are held by women. In a broader sense it can also extend to moral authority, social privilege, and control of property. While those definitions apply in general English, ...

(female-led) herds of related individuals, with males leaving these groups to live solitarily upon reaching adolescence around 14–15 years of age. Adult males likely engaged in combat with each other during musth

Musth or must (from Persian, ) is a periodic condition in bull (male) elephants characterized by aggressive behavior in animals, aggressive behavior and accompanied by a large rise in reproductive hormones. It has been known in Asian elephan ...

similar to living elephants. Some straight-tusked elephant specimens appear to document injuries obtained in fights with conspecifics; particularly notable specimens include a large male specimen from Neumark Nord that has a deep puncture hole wound in its forehead with surrounding bone growth indicating that it had healed, as well as another large male from the same locality with a healed puncture hole wound in its scapula.

Like modern elephants, the herds would have been restricted to areas with available fresh water due to the greater hydration needs and lower mobility of the juveniles. Fossil tracks of newborns, calves and adults, which are likely of a herd of ''P. antiquus'', have been found in dune deposits in southern Spain, dating to the early Late Pleistocene ( Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5, around 130–80,000 years ago). Some straight-tusked elephant populations may have engaged in seasonal migrations, as occurs in living elephants. Due to their larger size, straight-tusked elephants are thought to have finished growing 10 to 15 years later than living elephants, continuing to grow after 50 years of age in males, and to around 40 years of age in females, the latter comparable to the growth period of African bush elephant bulls. They may also have lived longer than extant elephants, with lifespans perhaps in excess of 80 years.

Dental microwear Dental microwear analysis is a method to infer diet and behavior in extinct animals, especially in fossil specimens. It has been used on a variety of taxa, including hominids, victoriapithecids, amphicyonids, canids, ursids, hyaenids, hyaenodont ...

studies suggest that the diet of ''P. antiquus'' was highly variable, ranging from almost completely grazing

In agriculture, grazing is a method of animal husbandry whereby domestic livestock are allowed outdoors to free range (roam around) and consume wild vegetations in order to feed conversion ratio, convert the otherwise indigestible (by human diges ...

to almost completely browsing

Browsing is a kind of orienting strategy. It is supposed to identify something of relevance for the browsing organism. In context of humans, it is a metaphor taken from the animal kingdom. It is used, for example, about people browsing open sh ...

(feeding on leaves, stems and fruits of high-growing plants). However, microwear only reflects the diet in the last few days or weeks before death, so the observed dietary variation may be seasonal, as is the case with living elephants. Isotopic analysis of a specimen from Greece suggests that it was primarily browsing during the dry (presumably summer) months and consumed more grass during the wet (presumably winter) months. Dental mesowear analysis suggests that the diet also varied according to local environmental conditions, with individuals occupying more grass-dominated open environments having a greater grazing-related wear signal. Preserved stomach contents of German specimens found at Neumark Nord suggests that in temperate Europe, its diet included trees such as maple

''Acer'' is a genus of trees and shrubs commonly known as maples. The genus is placed in the soapberry family Sapindaceae.Stevens, P. F. (2001 onwards). Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 9, June 2008 nd more or less continuously updated si ...

, linden/lime, hornbeam

Hornbeams are hardwood trees in the plant genus ''Carpinus'' in the family Betulaceae. Its species occur across much of the temperateness, temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

Common names

The common English name ''hornbeam'' derives ...

, hazel

Hazels are plants of the genus ''Corylus'' of deciduous trees and large shrubs native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. The genus is usually placed in the birch family, Betulaceae,Germplasmgobills Information Network''Corylus''Rushforth, K ...

, alder

Alders are trees of the genus ''Alnus'' in the birch family Betulaceae. The genus includes about 35 species of monoecious trees and shrubs, a few reaching a large size, distributed throughout the north temperate zone with a few species ex ...

, beech

Beech (genus ''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to subtropical (accessory forest element) and temperate (as dominant element of Mesophyte, mesophytic forests) Eurasia and North America. There are 14 accepted ...

, ash, oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

, elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus ''Ulmus'' in the family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical- montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ...

, spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' ( ), a genus of about 40 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal ecosystem, boreal (taiga) regions of the Northern hemisphere. ''Picea'' ...

and possibly juniper

Junipers are coniferous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Juniperus'' ( ) of the cypress family Cupressaceae. Depending on the taxonomy, between 50 and 67 species of junipers are widely distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere as far south ...

, as well as other plants like ivy, '' Pyracantha'', '' Artemisia,'' mistletoe

Mistletoe is the common name for obligate parasite, obligate parasitic plant, hemiparasitic plants in the Order (biology), order Santalales. They are attached to their host tree or shrub by a structure called the haustorium, through which they ...

('' Viscum''), thistle

Thistle is the common name of a group of flowering plants characterized by leaves with sharp spikes on the margins, mostly in the family Asteraceae. Prickles can also occur all over the planton the stem and on the flat parts of the leaves. T ...

s ('' Carduus'' and ''Cirsium

''Cirsium'' is a genus of Perennial plant, perennial and Biennial plant, biennial flowering plants in the Asteraceae, one of several genera known commonly as thistles. They are more precisely known as plume thistles. These differ from other thist ...

''), grass and sedges

The Cyperaceae () are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large; botanists have described some 5,500 known species in about 90 generathe largest being the "true sedges" (genu ...

(''Carex

''Carex'' is a vast genus of over 2,000 species of grass-like plants in the family (biology), family Cyperaceae, commonly known as sedges (or seg, in older books). Other members of the family Cyperaceae are also called sedges, however those of ge ...

''), as well as members of Apiaceae

Apiaceae () or Umbelliferae is a family of mostly aromatic flowering plants named after the type genus ''Apium,'' and commonly known as the celery, carrot, or parsley family, or simply as umbellifers. It is the 16th-largest family of flowering p ...

, Lauraceae

Lauraceae, or the laurels, is a plant Family (biology), family that includes the bay laurel, true laurel and its closest relatives. This family comprises about 2850 known species in about 45 genus (biology), genera worldwide. They are dicotyled ...

, Rosaceae

Rosaceae (), the rose family, is a family of flowering plants that includes 4,828 known species in 91 genera.

The name is derived from the type genus '' Rosa''. The family includes herbs, shrubs, and trees. Most species are deciduous, but som ...

, Caryophyllaceae

Caryophyllaceae, commonly called the pink family or carnation family, is a family (biology), family of flowering plants. It is included in the dicotyledon order Caryophyllales in the APG III system, alongside 33 other families, including Amaranth ...

and Asteraceae

Asteraceae () is a large family (biology), family of flowering plants that consists of over 32,000 known species in over 1,900 genera within the Order (biology), order Asterales. The number of species in Asteraceae is rivaled only by the Orchi ...

(including the subfamily Lactuceae).

Straight-tusked elephants rarely coexisted alongside mammoths, although they occasionally did so, like at the Ilford locality in Britain that dates to the Marine Isotope Stage

Marine isotope stages (MIS), marine oxygen-isotope stages, or oxygen isotope stages (OIS), are alternating warm and cool periods in the Earth's paleoclimate, deduced from Oxygen isotope ratio cycle, oxygen isotope data derived from deep sea core ...

(MIS) 7 interglacial (~200,000 years ago) and where both steppe mammoths and ''P. antiquus'' are found. At this locality, the two species appear to have engaged in dietary niche partitioning

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for e ...

.

During interglacial periods, ''P. antiquus'' existed as part of the ''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' large-mammal assemblage, along with other temperate adapted

During interglacial periods, ''P. antiquus'' existed as part of the ''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' large-mammal assemblage, along with other temperate adapted megafauna

In zoology, megafauna (from Ancient Greek, Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and Neo-Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") are large animals. The precise definition of the term varies widely, though a common threshold is approximately , this lower en ...

species, including the hippopotamus

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Sahar ...

(''Hippopotamus amphibius''), rhinoceroses belonging to the genus ''Stephanorhinus

''Stephanorhinus'' is an extinct genus of two-horned rhinoceros native to Eurasia and North Africa that lived during the Late Pliocene to Late Pleistocene. Species of ''Stephanorhinus'' were the predominant and often only species of rhinoceros in ...

'' (Merck's rhinoceros

''Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis'', also known as Merck's rhinoceros (or the less commonly, the forest rhinoceros) is an extinct species of rhinoceros belonging to the genus ''Stephanorhinus'' that lived from the end of the Early Pleistocene (arou ...

''S. kirchbergensis'' and the narrow-nosed rhinoceros

The narrow-nosed rhinoceros (''Stephanorhinus hemitoechus''), also known as the steppe rhinoceros is an extinct species of rhinoceros belonging to the genus '' Stephanorhinus'' that lived in western Eurasia, including Europe, and West Asia, as ...

''S. hemitoechus''), the European water buffalo (''Bubalus murrensis''), bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

(''Bison'' spp.), Irish elk (''Megaloceros giganteus''), aurochs

The aurochs (''Bos primigenius''; or ; pl.: aurochs or aurochsen) is an extinct species of Bovini, bovine, considered to be the wild ancestor of modern domestic cattle. With a shoulder height of up to in bulls and in cows, it was one of t ...

(''Bos primigenius''), fallow deer

Fallow deer is the common name for species of deer in the genus ''Dama'' of subfamily Cervinae. There are two living species, the European fallow deer (''Dama dama''), native to Europe and Anatolia, and the Persian fallow deer (''Dama mesopotamic ...

(''Dama'' spp.), roe deer (''Capreolus capreolus),'' red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

(''Cervus elaphus''), moose

The moose (: 'moose'; used in North America) or elk (: 'elk' or 'elks'; used in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is the world's tallest, largest and heaviest extant species of deer and the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is also the tal ...

(''Alces alces''), wild horse

The wild horse (''Equus ferus'') is a species of the genus Equus (genus), ''Equus'', which includes as subspecies the modern domestication of the horse, domesticated horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') as well as the Endangered species, endangered ...

(''Equus ferus'') and wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

(''Sus scrofa''). Carnivores included Eurasian lynx

The Eurasian lynx (''Lynx lynx'') is one of the four wikt:extant, extant species within the medium-sized wild Felidae, cat genus ''Lynx''. It is widely distributed from Northern Europe, Northern, Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe to Cent ...

(''Lynx lynx'') European leopards (''Panthera pardus spelaea''), cave hyenas (''Crocuta spelaea''), cave lions (''Panthera spelaea''), wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the grey wolf or gray wolf, is a canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, including the dog and dingo, though gr ...

(''Canis lupus'') and brown bear

The brown bear (''Ursus arctos'') is a large bear native to Eurasia and North America. Of the land carnivorans, it is rivaled in size only by its closest relative, the polar bear, which is much less variable in size and slightly bigger on av ...

s (''Ursus arctos''). Some authors have argued, in accordance with the Vera/wood-pasture hypothesis, that the effects of straight-tusked elephants and other extinct megafauna on vegetation likely resulted in increased openness of woodland habitats, though this conclusion has been disputed by other authors.

Potential gnaw marks suggested to have been made by cave hyenas and cave lions on the bones of straight-tusked elephants have been reported at some localities, which suggests that these species likely at least scavenged on the remains of straight-tusked elephants like lions and spotted hyenas do on elephants in Africa today. Remains of juvenile straight-tusked elephants are also known from Kirkdale Cave in northern England, a well known cave hyena den.

Relationship with humans

Remains of straight-tusked elephants at numerous sites are associated with stone tools and/or bear cut and percussion marks indicative of butchery by archaic humans. At most sites it is unclear whether the elephants were hunted or scavenged, though both scavenging of already dead elephants and active hunting are likely to have occurred. Straight-tusked elephant butchery sites have been found in Israel, Spain, Italy, Greece, Britain, and Germany. These sites are likely attributable to ''Homo heidelbergensis

''Homo heidelbergensis'' is a species of archaic human from the Middle Pleistocene of Europe and Africa, as well as potentially Asia depending on the taxonomic convention used. The species-level classification of ''Homo'' during the Middle Pleis ...

'' and Neanderthals

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

. Stone tools used at these sites include flakes, choppers, bifacial tools like handaxes

A hand axe (or handaxe or Acheulean hand axe) is a prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history. It is made from stone, usually flint or chert that has been "reduced" and shaped from a larger piece by kn ...

, as well as cores''.'' At some sites, the bones of straight-tusked elephants and in at least one case their ivory were used to make tools. There is evidence that exploitation of straight-tusked elephants in Europe increased and became more systematic from the mid-Middle Pleistocene (around 500,000 years ago) onwards. Based on analysis of sites of straight-tusked elephants with cut marks and/or artifacts, it has been argued that there is little evidence that straight-tusked elephants were targeted preferentially over smaller animals. Most individuals at these sites are subadult to adult and primarily male in sex. The male sex bias likely both represents the fact that adult males, despite their larger size, were more vulnerable targets due to their solitary nature, as well as the tendency of adult male elephants to engage in risky behavior causing them to more frequently die in natural traps, as well as being weakened or killed by injuries caused by combat with other male elephants during musth.

At the Lehringen site in north Germany, dating to the Eemian/Last Interglacial (around 130–115,000 years ago) a skeleton of a mature adult ''P. antiquus'', around 45 years of age, was found with a complete (though currently fractured) spear/lance between its ribs, with flint artifacts found close by, providing unequivocal evidence that this specimen was hunted,H. Thieme, S. Veil, Neue Untersuchungen zum eemzeitlichen Elefanten-Jagdplatz Lehringen, Ldkr. Verden. ''Kunde'' 36, 11–58 (1985). though it has been suggested the elephant may have already been mired prior to being killed. The spear/lance, which is around long, is made of yew wood, specifically of the species ''

At the Lehringen site in north Germany, dating to the Eemian/Last Interglacial (around 130–115,000 years ago) a skeleton of a mature adult ''P. antiquus'', around 45 years of age, was found with a complete (though currently fractured) spear/lance between its ribs, with flint artifacts found close by, providing unequivocal evidence that this specimen was hunted,H. Thieme, S. Veil, Neue Untersuchungen zum eemzeitlichen Elefanten-Jagdplatz Lehringen, Ldkr. Verden. ''Kunde'' 36, 11–58 (1985). though it has been suggested the elephant may have already been mired prior to being killed. The spear/lance, which is around long, is made of yew wood, specifically of the species ''Taxus baccata

''Taxus baccata'' is a species of evergreen tree in the family (botany), family Taxaceae, native to Western Europe, Central Europe and Southern Europe, as well as Northwest Africa, and parts of Southwest Asia.Rushforth, K. (1999). ''Trees of Bri ...

,'' which has both a durable and elastic wood, properties that may have been deliberately selected for.Milks, A. (2020) Yew wood, would you? An exploration of the selection of wood for Pleistocene spears

'' In: Berihuete-Azorin, M., Martin Seijo, M., Lopez-Bulto, O. and Pique, R. (eds.) The Missing Woodland Resources: Archaeobotanical studies of the use of plant raw materials. Advances in Archaeobotany, 6 (6). Barkhuis Publishing, Groningen, pp. 5-22. The Lehringen spear/lance is one of the oldest known wooden weapons after the Clacton spearhead (also made of yew wood) and the

Schöningen spears

The Schöningen spears are a set of ten Palaeolithic wooden weapons that were excavated between 1994 and 1999 from the 'Schöningen site, Spear Horizon' in the Open-pit mining, open-cast lignite mine in Schöningen, Helmstedt (district), Helmstedt ...

, has been suggested to have served as a handheld thrusting spear rather than as a throwing weapon. The current c-curved bent shape of the spear suggests that the spear was thrust upwards into the elephants abdomen, and may have been deformed by the elephant falling on it (the current fractured state of the spear is thought to have been due to much later sediment compaction).

Studies in 2023 proposed that in addition to Lehringen, the Neumark Nord, Taubach and Gröbern sites, which show evidence of systematic butchery, provided evidence of widespread hunting of straight-tusked elephants by Neanderthals during the Eemian in Germany. The remains of at least 57 elephants were found at Neumark Nord; the study authors estimated that they accumulated over a time span of around 300 years and that one elephant was hunted once every 5–6 years at the site.At the Lower Palaeolithic

The Lower Paleolithic (or Lower Palaeolithic) is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3.3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears ...

Bilzingsleben site in Germany and Stránská Skála 1 site in the Czech Republic, bones of straight-tusked elephants have been found engraved with multiple nearly straight lines, either parallel or converging, of unclear purpose.

There are no cave painting

In archaeology, cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric art, prehistoric origin. These paintings were often c ...

s that unambiguously depict ''P. antiquus''. An outline drawing of an elephant in El Castillo cave in Cantabria, Spain, as well as a drawing from Vermelhosa in Portugal have been suggested to possibly depict it, but these could also potentially depict woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived from the Middle Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with the African ...

s.

Extinction

''Palaeoloxodon antiquus'' retreated from northern Europe after the end of the Eemian interglacial around 115,000 years ago due to climatic conditions becoming unfavourable, and fossils after that time during the Last Glacial Period are rare. In Britain, the species may have persisted until around 87,000 years ago based on remains found in Bacon Hole in Wales. A molar from the cave deposits of Grotta Guattari in central Italy has been suggested to date to around 57,000 years ago, though other studies have found it to have an older early Late Pleistocene age, and later dating done in 2023 suggested an age of deposition in the cave of around 66–65,000 years ago. Another late Italian record has been reported fromMousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an Industry (archaeology), archaeological industry of Lithic technology, stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and with the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and We ...

layers in Barma Grande cave in northwest Italy, probably dating to around the same time as Grotta Guattari, which has been suggested to display evidence of butchery by Neanderthals. Other late remains have been reported from several sites in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, including El Castillo cave in northern Spain, which were initially radiocarbon dated to 43,000 years ago, with later calibration

In measurement technology and metrology, calibration is the comparison of measurement values delivered by a device under test with those of a calibration standard of known accuracy. Such a standard could be another measurement device of known ...

suggesting an age of around 49,570–44,250 years Before Present

Before Present (BP) or "years before present (YBP)" is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology, and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred relative to the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Because ...

, and Foz do Enxarrique (a sequence of terrace deposits of the Tagus river) in central-eastern Portugal, originally dated to around 34–33,000 years ago, but later revised to around 44,000 years ago. A late date of around 37,400 years ago has been reported from a single molar found in the North Sea off the coast of the Netherlands, but it has been suggested that this date needs independent confirmation, due to only representing a single sample. Some authors have suggested that ''P. antiquus'' likely survived until around 28,000 years ago in the southern Iberian Peninsula based on footprints found in Southwest Portugal and Gibraltar. While some authors have argued that climate change was primarily responsible for the extinction of the straight-tusked elephant, others have argued that climate change alone cannot account for the species extinction. Human hunting may have played a contributory role, but the importance of this is uncertain.

Some island dwarf elephant

Dwarf elephants are prehistoric members of the order Proboscidea which, through the process of allopatric speciation on islands, evolved much smaller body sizes (around shoulder height) in comparison with their immediate ancestors. Dwarf elephant ...

descendants survived considerably later than the youngest confirmed straight tusked elephant records, with the Sicilian ''Palaeoloxodon cf. mnaidriensis'' surviving until sometime after 32,000 years ago, with one record perhaps as late as 20,000-19,000 years ago, while '' Palaeoloxodon cypriotes'' on Cyprus survived until at least around 12–11,000 years ago.

The extinction was part of the Late Pleistocene megafauna extinctions, which resulted in the extinction of most large terrestrial mammals globally. The extinction of ''P. antiquus'' and other temperate adapted European megafauna has resulted in a severe loss of functional diversity in European ecosystems.

Notes

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q1377999 Palaeoloxodon Pleistocene proboscideans Pleistocene species Pleistocene mammals of Europe Pleistocene mammals of Asia Fossil taxa described in 1847