St. Anselm on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

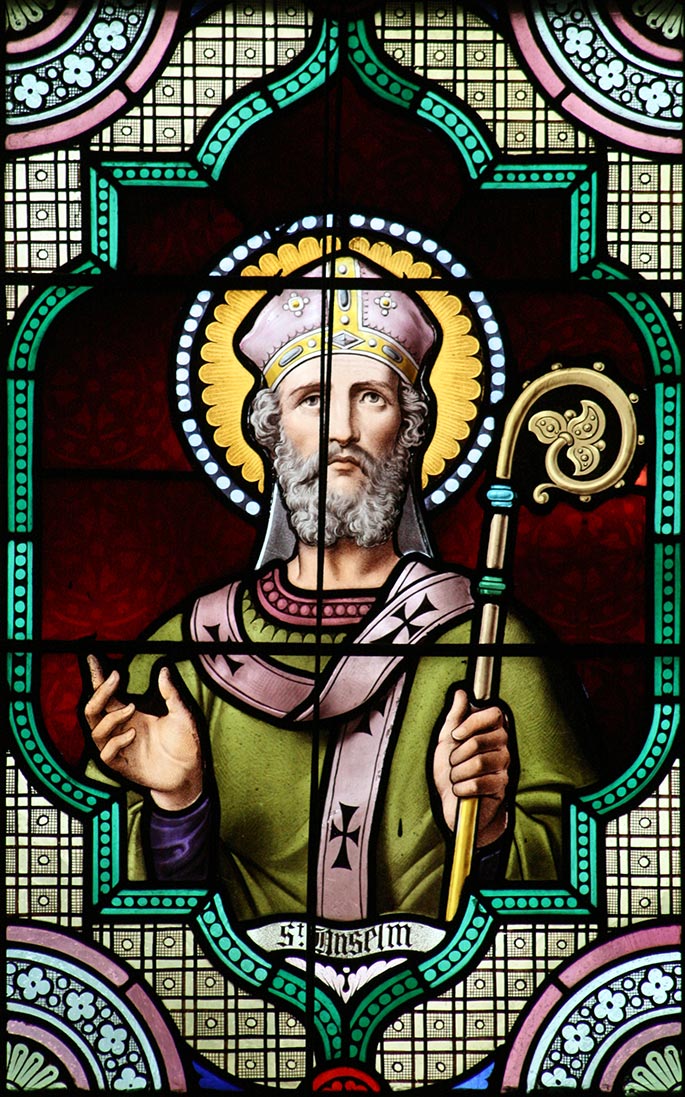

Anselm of Canterbury OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also known as (, ) after his birthplace and () after his

Following the

Following the  At Christmas, William II pledged by the Holy Face of Lucca that neither Anselm nor any other would sit at Canterbury while he lived but in March he fell seriously ill at Alveston. Believing his

At Christmas, William II pledged by the Holy Face of Lucca that neither Anselm nor any other would sit at Canterbury while he lived but in March he fell seriously ill at Alveston. Believing his

Although the work was largely handled by Christ Church's priors Ernulf (1096–1107) and Conrad (1108–1126), Anselm's episcopate also saw the expansion of

Although the work was largely handled by Christ Church's priors Ernulf (1096–1107) and Conrad (1108–1126), Anselm's episcopate also saw the expansion of

Upon William's return, Anselm insisted that he travel to the court of Urban II to secure the pallium that legitimized his office. On 25 February 1095, the

Upon William's return, Anselm insisted that he travel to the court of Urban II to secure the pallium that legitimized his office. On 25 February 1095, the

Anselm chose to depart in October 1097. Although Anselm retained his nominal title, William immediately seized the revenues of his bishopric and retained them til death. From

Anselm chose to depart in October 1097. Although Anselm retained his nominal title, William immediately seized the revenues of his bishopric and retained them til death. From

In 1107, the Concordat of London formalized the agreements between the king and archbishop, Henry formally renounced the right of English kings to invest the bishops of the church. The remaining two years of Anselm's life were spent in the duties of his archbishopric. He succeeded in getting Paschal to send the pallium for the

In 1107, the Concordat of London formalized the agreements between the king and archbishop, Henry formally renounced the right of English kings to invest the bishops of the church. The remaining two years of Anselm's life were spent in the duties of his archbishopric. He succeeded in getting Paschal to send the pallium for the

More probably, Anselm intended his "single argument" to include most of the rest of the work as well, wherein he establishes the attributes of God and their compatibility with one another. Continuing to construct a being greater than which nothing else can be conceived, Anselm proposes such a being must be "just, truthful, happy, and whatever it is better to be than not to be". Chapter 6 specifically enumerates the additional qualities of awareness, omnipotence, mercifulness, impassibility (inability to suffer), and immateriality; Chapter 11, self-existent, wisdom, goodness, happiness, and permanence; and Chapter 18, unity. Anselm addresses the question-begging nature of "greatness" in this formula partially by appeal to intuition and partially by independent consideration of the attributes being examined. The incompatibility of, e.g., omnipotence, justness, and mercifulness are addressed in the abstract by reason, although Anselm concedes that specific acts of God are a matter of revelation beyond the scope of reasoning. At one point during the 15th chapter, he reaches the conclusion that God is "not only that than which nothing greater can be thought but something greater than can be thought". In any case, God's unity is such that all of his attributes are to be understood as facets of a single nature: "all of them are one and each of them is entirely what od isand what the other are". This is then used to argue for the triune nature of the God,

More probably, Anselm intended his "single argument" to include most of the rest of the work as well, wherein he establishes the attributes of God and their compatibility with one another. Continuing to construct a being greater than which nothing else can be conceived, Anselm proposes such a being must be "just, truthful, happy, and whatever it is better to be than not to be". Chapter 6 specifically enumerates the additional qualities of awareness, omnipotence, mercifulness, impassibility (inability to suffer), and immateriality; Chapter 11, self-existent, wisdom, goodness, happiness, and permanence; and Chapter 18, unity. Anselm addresses the question-begging nature of "greatness" in this formula partially by appeal to intuition and partially by independent consideration of the attributes being examined. The incompatibility of, e.g., omnipotence, justness, and mercifulness are addressed in the abstract by reason, although Anselm concedes that specific acts of God are a matter of revelation beyond the scope of reasoning. At one point during the 15th chapter, he reaches the conclusion that God is "not only that than which nothing greater can be thought but something greater than can be thought". In any case, God's unity is such that all of his attributes are to be understood as facets of a single nature: "all of them are one and each of them is entirely what od isand what the other are". This is then used to argue for the triune nature of the God,

All of Anselm's

All of Anselm's

Two biographies of Anselm were written shortly after his death by his chaplain and secretary

Two biographies of Anselm were written shortly after his death by his chaplain and secretary

Anselm's

Anselm's  Anselm was proclaimed a

Anselm was proclaimed a

Vols. CLVIII

nbsp;

of the 2nd series of his ''

) * * *

Vicifons

and th

* St Anselm's works a

Wikisource

th

Christian Classics Ethereal Library

and th

Online Library of Liberty

St Anselm's works and related essays

at Prof. Jasper Hopkin's homepage. * *

* ttps://www.academiestanselme.eu/ Académie Saint Anselme d'Aoste {{DEFAULTSORT:Anselm of Canterbury 1030s births 1109 deaths 11th-century Christian abbots 11th-century Christian mystics 11th-century English Roman Catholic archbishops 11th-century English Roman Catholic theologians 11th-century Italian philosophers 11th-century Italian writers 11th-century people from the Savoyard State 11th-century writers in Latin 12th-century Christian mystics 12th-century English Roman Catholic archbishops 12th-century English Roman Catholic theologians 12th-century Italian philosophers Anglican saints Archbishops of Canterbury Augustinian philosophers Benedictine abbots Benedictine mystics Benedictine philosophers Benedictine saints Benedictine theologians British critics of atheism Burgundian monks Burials at Canterbury Cathedral Catholic philosophers Christian apologists Doctors of the Church Italian abbots Italian Benedictines Italian male non-fiction writers Italian religious writers Italian Roman Catholic saints Italian Roman Catholic writers Lombard monks Lutheran saints Ontologists People from Aosta Valley Pre-Reformation Anglican saints Pre-Reformation saints of the Lutheran liturgical calendar Scholastic philosophers Year of birth uncertain

monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Monasticism, monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in Cenobitic monasticism, communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a ...

, was an Italian Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

monk, abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

, philosopher, and theologian of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, who served as Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

from 1093 to 1109.

As Archbishop of Canterbury, he defended the church's interests in England amid the Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy or Investiture Contest (, , ) was a conflict between church and state in medieval Europe, the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture), abbots of monasteri ...

. For his resistance to the English kings William II and Henry I, he was exiled twice: once from 1097 to 1100 and then from 1105 to 1107. While in exile, he helped guide the Greek Catholic Greek Catholic Church or Byzantine-Catholic Church may refer to:

* The Catholic Church in Greece

* The Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Ea ...

bishops of southern Italy to adopt Roman Rite

The Roman Rite () is the most common ritual family for performing the ecclesiastical services of the Latin Church, the largest of the ''sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. The Roman Rite governs Rite (Christianity) ...

s at the Council of Bari. He worked for the primacy of Canterbury over the Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

and over the bishops of Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, and at his death he appeared to have been successful; however, Pope Paschal II later reversed the papal decisions on the matter and restored York's earlier status.

Beginning at Bec, Anselm composed dialogues and treatises with a rational and philosophical

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

approach, which have sometimes caused him to be credited as the founder of Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

. Despite his lack of recognition in this field in his own time, Anselm is now famous as the originator of the ontological argument

In the philosophy of religion, an ontological argument is a deductive philosophical argument, made from an ontological basis, that is advanced in support of the existence of God. Such arguments tend to refer to the state of being or existing. ...

for the existence of God

The existence of God is a subject of debate in the philosophy of religion and theology. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God (with the same or similar arguments also generally being used when talking about the exis ...

and of the satisfaction theory of atonement

Atonement, atoning, or making amends is the concept of a person taking action to correct previous wrongdoing on their part, either through direct action to undo the consequences of that act, equivalent action to do good for others, or some othe ...

.

After his death, Anselm was canonized as a saint; his feast day is 21 April. He was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church

Doctor of the Church (Latin: ''doctor'' "teacher"), also referred to as Doctor of the Universal Church (Latin: ''Doctor Ecclesiae Universalis''), is a title given by the Catholic Church to saints recognized as having made a significant contribut ...

by a papal bull of Pope Clement XI

Pope Clement XI (; ; ; 23 July 1649 – 19 March 1721), born Giovanni Francesco Albani, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 23 November 1700 to his death in March 1721.

Clement XI was a patron of the arts an ...

in 1720.

Biography

Family

Anselm was born in or aroundAosta

Aosta ( , , ; ; , or ; or ) is the principal city of the Aosta Valley, a bilingual Regions of Italy, region in the Italy, Italian Alps, north-northwest of Turin. It is situated near the Italian entrance of the Mont Blanc Tunnel and the G ...

in Upper Burgundy

Upper Burgundy (; ) was a historical region in the early medieval Burgundy, and a distinctive realm known as the ''Kingdom of Upper Burgundy'', that existed from 888 to 933, when it was incorporated into the reunited Kingdom of Burgundy, that ...

sometime between April 1033 and April 1034. The area now forms part of the Republic of Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, but Aosta had been part of the post-Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty ( ; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Arnulfing and Pippinid c ...

Kingdom of Burgundy

Kingdom of Burgundy was a name given to various successive Monarchy, kingdoms centered in the historical region of Burgundy during the Middle Ages. The heartland of historical Burgundy correlates with the border area between France and Switze ...

until the death of the childless Rudolph III in 1032. The Emperor Conrad II and Odo II, Count of Blois then went to war over the succession. Humbert the White-Handed, Count of Maurienne, so distinguished himself that he was granted a new county carved out of the secular holdings of the bishop of Aosta. Humbert's son Otto

Otto is a masculine German given name and a surname. It originates as an Old High German short form (variants '' Audo'', '' Odo'', '' Udo'') of Germanic names beginning in ''aud-'', an element meaning "wealth, prosperity".

The name is recorded fr ...

was subsequently permitted to inherit the extensive March of Susa through his wife Adelaide

Adelaide ( , ; ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital and most populous city of South Australia, as well as the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. The name "Adelaide" may refer to ei ...

in preference to her uncle's families, who had supported the effort to establish an independent Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

under William V, Duke of Aquitaine. Otto and Adelaide's unified lands then controlled the most important passes in the Western Alps

The Western Alps are the western part of the Alps, Alpine Range including the southeastern part of France (e.g. Savoie), the whole of Monaco, the northwestern part of Italy (i.e. Piedmont and the Aosta Valley) and the southwestern part of Switzer ...

and formed the county of Savoy whose dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family, usually in the context of a monarchy, monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A dynasty may also be referred to as a "house", "family" or "clan", among others.

H ...

would later rule the kingdoms of Sardinia and Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

.

Records during this period are scanty, but both sides of Anselm's immediate family appear to have been dispossessed by these decisions in favour of their extended relations. His father Gundulph or Gundulf or Gondulphe was a Lombard noble, probably one of Adelaide's Arduinici

The Arduinici were a nobility, noble Franks, Frankish family that immigrated to Italy in the early tenth century, possibly from Neustria. They were descended from and take their name after one Arduin (Hardouin).

The first of the Arduinici to ente ...

uncles or cousins; his mother Ermenberge was almost certainly the granddaughter of Conrad the Peaceful, related both to the Anselmid bishops of Aosta and to the heirs of Henry II who had been passed over in favour of Conrad. The marriage was thus probably arranged for political reasons but proved ineffective in opposing Conrad after his successful annexation of Burgundy on 1 August 1034. ( Bishop Burchard subsequently revolted against imperial control but was defeated and was ultimately translated to the diocese of Lyon

The Archdiocese of Lyon (; ), formerly the Archdiocese of Lyon–Vienne–Embrun, is a Latin Church metropolis (religious jurisdiction), metropolitan archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. The archbishops of Lyon are also called Primate o ...

.) Ermenberge appears to have been the wealthier partner in the marriage. Gundulph moved to his wife's town, where she held a palace, most likely near the cathedral, along with a villa in the valley

A valley is an elongated low area often running between hills or mountains and typically containing a river or stream running from one end to the other. Most valleys are formed by erosion of the land surface by rivers or streams over ...

. Anselm's father is sometimes described as having a harsh and violent temper but contemporary accounts merely portray him as having been overgenerous or careless with his wealth; Meanwhile, Anselm's mother Ermenberge, patient and devoutly religious, made up for her husband's faults by her prudent management of the family estates. In later life, there are records of three relations who visited Bec: Folceraldus, Haimo, and Rainaldus. The first repeatedly attempted to exploit Anselm's renown, but was rebuffed since he already had his ties to another monastery, whereas Anselm's attempts to persuade the other two to join the Bec community were unsuccessful.

Early life

At the age of fifteen, Anselm felt the call to enter a monastery but, failing to obtain his father's consent, he was refused by the abbot. The illness he then suffered has been considered by some apsychosomatic

Somatic symptom disorder, also known as somatoform disorder or somatization disorder, is chronic somatization. One or more chronic physical symptoms coincide with excessive and maladaptive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors connected to those symp ...

effect of his disappointment, but upon his recovery he gave up his studies and for a time lived a carefree life.

Following the death of his mother, probably at the birth of his sister Richera, Anselm's father repented his own earlier lifestyle but professed his new faith with a severity that the boy found likewise unbearable. When Gundulph entered a monastery, Anselm, at age 23, left home with a single attendant, crossed the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

, and wandered through Burgundy

Burgundy ( ; ; Burgundian: ''Bregogne'') is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

for three years. His countryman Lanfranc of Pavia

Pavia ( , ; ; ; ; ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy, in Northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino (river), Ticino near its confluence with the Po (river), Po. It has a population of c. 73,086.

The city was a major polit ...

was then prior

The term prior may refer to:

* Prior (ecclesiastical), the head of a priory (monastery)

* Prior convictions, the life history and previous convictions of a suspect or defendant in a criminal case

* Prior probability, in Bayesian statistics

* Prio ...

of the Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

abbey of Bec in Normandy. Attracted by Lanfranc's reputation, Anselm reached Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

in 1059. After spending some time in Avranches

Avranches (; ) is a commune in the Manche department, and the region of Normandy, northwestern France. It is a subprefecture of the department. The inhabitants are called ''Avranchinais''.

History Middle Ages

By the end of the Roman period, th ...

, he returned the next year. His father having died, he consulted with Lanfranc as to whether to return to his estates and employ their income in providing alms for the poor or to renounce them, becoming a hermit

A hermit, also known as an eremite (adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a Chr ...

or a monk at Bec or Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in ...

. Given what he saw as his own conflict of interest, Lanfranc sent Anselm to Maurilius, the archbishop of Rouen

The Archdiocese of Rouen (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Rothomagensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Rouen'') is a Latin Church archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. As one of the fifteen Archbishops of France, the Archbishop of Rouen's ecclesi ...

, who convinced him to enter Bec as a novice

A novice is a person who has entered a religious order and is under probation, before taking vows. A ''novice'' can also refer to a person (or animal e.g. racehorse) who is entering a profession with no prior experience.

Religion Buddhism

...

at the age of 27. Probably in his first year, he wrote his first work on philosophy, a treatment of Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

paradoxes called the '' Grammarian''. Over the next decade, the Rule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' () is a book of precepts written in Latin by St. Benedict of Nursia (c. AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Rule is summed up in the motto of th ...

reshaped his thought.

Abbot of Bec

Early years

Three years later, in 1063, Duke William II summoned Lanfranc to serve as the abbot of his new abbey of St Stephen atCaen

Caen (; ; ) is a Communes of France, commune inland from the northwestern coast of France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Calvados (department), Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inha ...

and the monks of Bec, despite the initial hesitation of some on account of his youth, elected Anselm prior. A notable opponent was a young monk named Osborne. Anselm overcame his hostility first by praising, indulging, and privileging him in all things despite his hostility and then, when his affection and trust were gained, gradually withdrawing all preference until he upheld the strictest obedience. Along similar lines, he remonstrated with a neighbouring abbot who complained that his charges were incorrigible despite being beaten "night and day". After fifteen years, in 1078, Anselm was unanimously elected as Bec's abbot following the death of its founder, the warrior-monk Herluin. He was blessed as abbot by Gilbert d'Arques, Bishop of Évreux, on 22 February 1079.

Under Anselm's direction, Bec became the foremost seat of learning in Europe, attracting students from France, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, and elsewhere. During this time, he wrote the '' Monologion'' and ''Proslogion

The ''Proslogion'' () is a prayer (or meditation) written by the medieval cleric Saint Anselm of Canterbury between 1077 and 1078. In each chapter, Anselm juxtaposes contrasting attributes of God to resolve apparent contradictions in Christian ...

''. He then composed a series of dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

s on the nature of truth

Truth or verity is the Property (philosophy), property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth, 2005 In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise cor ...

, free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

, and the fall of Satan. When the nominalist

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

Roscelin attempted to appeal to the authority of Lanfranc and Anselm at his trial for the heresy of tritheism at Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital ...

in 1092, Anselm composed the first draft of '' De Fide Trinitatis'' as a rebuttal and as a defence of Trinitarianism

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, three ...

and universals

In metaphysics, a universal is what particular things have in common, namely characteristics or qualities. In other words, universals are repeatable or recurrent entities that can be instantiated or exemplified by many particular things. For exa ...

. The fame of the monastery grew not only from his intellectual achievements, however, but also from his good example and his loving, kindly method of discipline, particularly with the younger monks. There was also admiration for his spirited defence of the abbey's independence from lay and archiepiscopal control, especially in the face of Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester and the new Archbishop of Rouen, William Bona Anima __NOTOC__

William Bona Anima or Bonne-Âme (died 1110) was a medieval archbishop of Rouen, archbishop of archdiocese of Rouen, Rouen. He served from 1079 to 1110.

William was the son of Radbod, the bishop of Sées and was a canon at Rouen as well ...

.

In England

Following the

Following the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

in 1066, devoted lords had given the abbey extensive lands across the Channel. Anselm occasionally visited to oversee the monastery's property, to wait upon his sovereign William I of England

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was ...

(formerly Duke William II of Normandy), and to visit Lanfranc, who had been installed as archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

in 1070. He was respected by William I and the good impression he made while in Canterbury made him the favourite of its cathedral chapter as a future successor to Lanfranc. Instead, upon the archbishop's death in 1089, King William II—William Rufus or William the Red—refused the appointment of any successor and appropriated the see's lands and revenues for himself. Fearing the difficulties that would attend being named to the position in opposition to the king, Anselm avoided journeying to England during this time. The gravely ill Hugh, Earl of Chester, finally lured him over with three pressing messages in 1092, seeking advice on how best to handle the establishment of the new monastery of St Werburgh at Chester. Hugh had recovered by the time of Anselm's arrival, and Anselm was occupied four or five months organizing the new community. He then travelled to his former pupil Gilbert Crispin, abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

of Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, and waited, apparently delayed by the need to assemble the donors of Bec's new lands in order to obtain royal approval of the grants.

At Christmas, William II pledged by the Holy Face of Lucca that neither Anselm nor any other would sit at Canterbury while he lived but in March he fell seriously ill at Alveston. Believing his

At Christmas, William II pledged by the Holy Face of Lucca that neither Anselm nor any other would sit at Canterbury while he lived but in March he fell seriously ill at Alveston. Believing his sin

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered ...

ful behavior was responsible, he summoned Anselm to hear his confession

A confession is a statement – made by a person or by a group of people – acknowledging some personal fact that the person (or the group) would ostensibly prefer to keep hidden. The term presumes that the speaker is providing information that ...

and administer last rites

The last rites, also known as the Commendation of the Dying, are the last prayers and ministrations given to an individual of Christian faith, when possible, shortly before death. The Commendation of the Dying is practiced in liturgical Chri ...

. He published a proclamation releasing his captives, discharging his debts, and promising to henceforth govern according to the law. On 6 March 1093, he further nominated Anselm to fill the vacancy at Canterbury; the clerics gathered at court acclaiming him, forcing the crozier

A crozier or crosier (also known as a paterissa, pastoral staff, or bishop's staff) is a stylized staff that is a symbol of the governing office of a bishop or abbot and is carried by high-ranking prelates of Roman Catholic, Eastern Catholi ...

into his hands, and bodily carrying him to a nearby church amid a ''Te Deum

The ( or , ; from its incipit, ) is a Latin Christian hymn traditionally ascribed to a date before AD 500, but perhaps with antecedents that place it much earlier. It is central to the Ambrosian hymnal, which spread throughout the Latin ...

''. Anselm tried to refuse on the grounds of age and ill-health for months and the monks of Bec refused to give him permission to leave them. Negotiations were handled by the recently restored Bishop William of Durham and Robert, count of Meulan. On 24 August, Anselm gave King William the conditions under which he would accept the position, which amounted to the agenda of the Gregorian Reform

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–1080, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be na ...

: the king would have to return the Catholic Church lands which had been seized, accept his spiritual counsel, and forswear Antipope Clement III

Guibert or Wibert of Ravenna (8 September 1100) was an Italian prelate, archbishop of Ravenna, who was elected pope in 1080 in opposition to Pope Gregory VII and took the name Clement III. Gregory was the leader of the movement in the church w ...

in favour of Urban II. William Rufus was exceedingly reluctant to accept these conditions: he consented only to the first and, a few days afterwards, reneged on that, suspending preparations for Anselm's investiture

Investiture (from the Latin preposition ''in'' and verb ''vestire'', "dress" from ''vestis'' "robe") is a formal installation or ceremony that a person undergoes, often related to membership in Christian religious institutes as well as Christian kn ...

. Public pressure forced William to return to Anselm and in the end they settled on a partial return of Canterbury's lands as his own concession. Anselm received dispensation from his duties in Normandy, did homage to William, and—on 25 September 1093—was enthroned at Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the spiritual leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christianity, Ch ...

. The same day, William II finally returned the lands of the see.

From the mid-8th century, it had become the custom that metropolitan bishop

In Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan (alternative obsolete form: metropolite), is held by the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a Metropolis (reli ...

s could not be consecrated

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects (a ...

without a woollen pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : pallia) is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropolitan bish ...

given or sent by the pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

himself. Anselm insisted that he journey to Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

for this purpose but William would not permit it. Amid the Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy or Investiture Contest (, , ) was a conflict between church and state in medieval Europe, the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture), abbots of monasteri ...

, Pope Gregory VII and Emperor Henry IV had deposed each other twice; bishops loyal to Henry finally elected Guibert, archbishop of Ravenna, as a second pope. In France, Philip I had recognized Gregory and his successors Victor III and Urban II, but Guibert (as "Clement III") held Rome after 1084. William had not chosen a side and maintained his right to prevent the acknowledgement of either pope by an English subject prior to his choice. In the end, a ceremony was held to consecrate

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects ( ...

Anselm as archbishop on 4 December, without the pallium.

Archbishop of Canterbury

As archbishop, Anselm maintained his monastic ideals, including stewardship, prudence, and proper instruction, prayer and contemplation. Anselm advocated forreform

Reform refers to the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The modern usage of the word emerged in the late 18th century and is believed to have originated from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement, which ...

and interests of Canterbury. As such, he repeatedly pressed the English monarchy for support of the reform agenda. His principled opposition to royal prerogatives over the Catholic Church, meanwhile, twice led to his exile from England.

The traditional view of historians has been to see Anselm as aligned with the papacy against lay authority and Anselm's term in office as the English theatre of the Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy or Investiture Contest (, , ) was a conflict between church and state in medieval Europe, the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture), abbots of monasteri ...

begun by Pope Gregory VII and the emperor Henry IV. By the end of his life, he had proven successful, having freed Canterbury from submission to the English king, received papal recognition of the submission of wayward York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

and the Welsh bishops, and gained strong authority over the Irish bishops. He died before the Canterbury–York dispute was definitively settled, however, and Pope Honorius II finally found in favour of York instead.

Although the work was largely handled by Christ Church's priors Ernulf (1096–1107) and Conrad (1108–1126), Anselm's episcopate also saw the expansion of

Although the work was largely handled by Christ Church's priors Ernulf (1096–1107) and Conrad (1108–1126), Anselm's episcopate also saw the expansion of Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the spiritual leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christianity, Ch ...

from Lanfranc's initial plans. The eastern end was demolished and an expanded choir

A choir ( ), also known as a chorale or chorus (from Latin ''chorus'', meaning 'a dance in a circle') is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform or in other words ...

placed over a large and well-decorated crypt

A crypt (from Greek κρύπτη (kryptē) ''wikt:crypta#Latin, crypta'' "Burial vault (tomb), vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, Sarcophagus, sarcophagi, or Relic, religiou ...

, doubling the cathedral's length. The new choir formed a church unto itself with its own transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

s and a semicircular ambulatory

The ambulatory ( 'walking place') is the covered passage around a cloister or the processional way around the east end of a cathedral or large church and behind the high altar. The first ambulatory was in France in the 11th century but by the 13t ...

opening into three chapels.

Conflicts with William Rufus

Anselm's vision was of a Catholic Church with its own internal authority, which clashed with William II's desire for royal control over both church and State. One of Anselm's first conflicts with William came in the month he was consecrated. William II was preparing to wrestNormandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

from his elder brother, Robert II, and needed funds. Anselm was among those expected to pay him. He offered £500 but William refused, encouraged by his courtiers to insist on £1000 as a kind of annates

Annates ( or ; , from ', "year") were a payment from the recipient of an ecclesiastical benefice to the collating authorities. Eventually, they consisted of half or the whole of the first year's profits of a benefice; after the appropriation of th ...

for Anselm's elevation to archbishop. Anselm not only refused, he further pressed the king to fill England's other vacant positions, permit bishops to meet freely in councils, and to allow Anselm to resume enforcement of canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

, particularly against incestuous marriages, until he was ordered to silence. When a group of bishops subsequently suggested that William might now settle for the original sum, Anselm replied that he had already given the money to the poor and "that he disdained to purchase his master's favour as he would a horse or ass". The king being told this, he replied Anselm's blessing for his invasion would not be needed as "I hated him before, I hate him now, and shall hate him still more hereafter". Withdrawing to Canterbury, Anselm began work on the ''Cur Deus Homo

''Cur Deus Homo?'' (Latin for "Why asGod a Human?"), usually translated ''Why God Became a Man'', is a book written by Anselm of Canterbury in the period of 1094–1098. In this work he proposes the satisfaction view of the atonement

Atone ...

''.

Upon William's return, Anselm insisted that he travel to the court of Urban II to secure the pallium that legitimized his office. On 25 February 1095, the

Upon William's return, Anselm insisted that he travel to the court of Urban II to secure the pallium that legitimized his office. On 25 February 1095, the Lords Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual are the bishops of the Church of England who sit in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom. Up to 26 of the 42 diocesan bishops and archbishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual (not including retired bish ...

and Temporal of England met in a council at Rockingham to discuss the issue. The next day, William ordered the bishops not to treat Anselm as their primate or as Canterbury's archbishop, as he openly adhered to Urban. The bishops sided with the king, the Bishop of Durham

The bishop of Durham is head of the diocese of Durham in the province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler (bishop), Paul Butler was the most recent bishop of Durham u ...

presenting his case and even advising William to depose and exile Anselm. The nobles siding with Anselm, the conference ended in deadlock and the matter was postponed. Immediately following this, William secretly sent William Warelwast

William Warelwast (died 1137) was a medieval Norman cleric and Bishop of Exeter in England. Warelwast was a native of Normandy, but little is known about his background before 1087, when he appears as a royal clerk for King William II. Most o ...

and Gerard

Gerard is a masculine forename of Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic origin, variations of which exist in many Germanic and Romance languages. Like many other Germanic name, early Germanic names, it is dithematic, consisting of two meaningful ...

to Italy, prevailing on Urban to send a legate bearing Canterbury's pallium. Walter, bishop of Albano, was chosen and negotiated in secret with William's representative, the Bishop of Durham. The king agreed to publicly support Urban's cause in exchange for acknowledgement of his rights to accept no legates without invitation and to block clerics from receiving or obeying papal letters without his approval. William's greatest desire was for Anselm to be removed from office. Walter said that "there was good reason to expect a successful issue in accordance with the king's wishes" but, upon William's open acknowledgement of Urban as pope, Walter refused to depose the archbishop. William then tried to sell the pallium to others, failed, tried to extract a payment from Anselm for the pallium, but was again refused. William then tried to personally bestow the pallium to Anselm, an act connoting the church's subservience to the throne, and was again refused. In the end, the pallium was laid on the altar at Canterbury, whence Anselm took it on 10 June 1095.

The First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

was declared at the Council of Clermont

The Council of Clermont was a mixed synod of ecclesiastics and laymen of the Catholic Church, called by Pope Urban II and held from 17 to 27 November 1095 at Clermont, Auvergne, at the time part of the Duchy of Aquitaine.

While the council ...

in November. Despite his service for the king which earned him rough treatment from Anselm's biographer Eadmer

Eadmer or Edmer ( – ) was an English historian, theologian, and ecclesiastic. He is known for being a contemporary biographer of his archbishop and companion, Saint Anselm, in his ''Vita Anselmi'', and for his ''Historia novorum i ...

, upon the grave illness of the Bishop of Durham

The bishop of Durham is head of the diocese of Durham in the province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler (bishop), Paul Butler was the most recent bishop of Durham u ...

in December, Anselm journeyed to console and bless him on his deathbed. Over the next two years, William opposed several of Anselm's efforts at reform—including his right to convene a council—but no overt dispute is known. However, in 1094, the Welsh had begun to recover their lands from the Marcher Lords

A marcher lord () was a noble appointed by the king of England to guard the border (known as the Welsh Marches) between England and Wales.

A marcher lord was the English equivalent of a margrave (in the Holy Roman Empire) or a marquis (in France ...

and William's 1095 invasion had accomplished little; two larger forays were made in 1097 against Cadwgan in Powys

Powys ( , ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It borders Gwynedd, Denbighshire, and Wrexham County Borough, Wrexham to the north; the English Ceremonial counties of England, ceremo ...

and Gruffudd in Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

. These were also unsuccessful and William was compelled to erect a series of border fortresses. He charged Anselm with having given him insufficient knights for the campaign and tried to fine him. In the face of William's refusal to fulfill his promise of church reform, Anselm resolved to proceed to Rome—where an army of French crusaders had finally installed Urban—in order to seek the counsel of the pope. William again denied him permission. The negotiations ended with Anselm being "given the choice of exile or total submission": if he left, William declared he would seize Canterbury and never again receive Anselm as archbishop; if he were to stay, William would impose his fine and force him to swear never again to appeal to the papacy.

First exile

Anselm chose to depart in October 1097. Although Anselm retained his nominal title, William immediately seized the revenues of his bishopric and retained them til death. From

Anselm chose to depart in October 1097. Although Anselm retained his nominal title, William immediately seized the revenues of his bishopric and retained them til death. From Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, Anselm wrote to Urban, requesting that he be permitted to resign his office. Urban refused but commissioned him to prepare a defence of the Western doctrine of the procession of the Holy Spirit against representatives from the Greek Church. Anselm arrived in Rome by April and, according to his biographer Eadmer

Eadmer or Edmer ( – ) was an English historian, theologian, and ecclesiastic. He is known for being a contemporary biographer of his archbishop and companion, Saint Anselm, in his ''Vita Anselmi'', and for his ''Historia novorum i ...

, lived beside the pope during the Siege of Capua in May. Count Roger's Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Rom ...

troops supposedly offered him food and other gifts but the count actively resisted the clerics' attempts to convert them to Catholicism.

At the Council of Bari in October, Anselm delivered his defence of the ''Filioque

( ; ), a Latin term meaning "and from the Son", was added to the original Nicene Creed, and has been the subject of great controversy between Eastern and Western Christianity. The term refers to the Son, Jesus Christ, with the Father, as th ...

'' and the use of unleavened bread

Unleavened bread is any of a wide variety of breads which are prepared without using rising agents such as yeast or sodium bicarbonate. The preparation of bread-like non-leavened cooked grain foods appeared in prehistoric times.

Unleavened br ...

in the Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

before 185 bishops. Although this is sometimes portrayed as a failed ecumenical dialogue, it is more likely that the "Greeks" present were the local bishops of Southern Italy, some of whom had been ruled by Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

as recently as 1071. The formal acts of the council have been lost and Eadmer's account of Anselm's speech principally consists of descriptions of the bishops' vestments

Vestments are liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christian religion, especially by Eastern Churches, Catholics (of all rites), Lutherans, and Anglicans. Many other groups also make use of liturgical garments; amo ...

, but Anselm later collected his arguments on the topic as . Under pressure from their Norman lords, the Italian Greeks seem to have accepted papal supremacy and Anselm's theology. The council also condemned William II. Eadmer credited Anselm with restraining the pope from excommunicating him, although others attribute Urban's politic nature.

Anselm was present in a seat of honour at the Easter Council The Easter Council was a church council held at Rome by Pope Urban II on Easter, Easter Day, 1099.

St Anselm, then in exile from his see at Diocese of Canterbury, Canterbury, was in attendance at the request of the Pope.

Among other acts, it st ...

at St Peter's in Rome the next year. There, amid an outcry to address Anselm's situation, Urban renewed bans on lay investiture and on clerics doing homage. Anselm departed the next day, first for Schiavi—where he completed his work ''Cur Deus Homo

''Cur Deus Homo?'' (Latin for "Why asGod a Human?"), usually translated ''Why God Became a Man'', is a book written by Anselm of Canterbury in the period of 1094–1098. In this work he proposes the satisfaction view of the atonement

Atone ...

''—and then for Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

.

Conflicts with Henry I

William Rufus was killed hunting in the New Forest on 2 August 1100. His brotherHenry

Henry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Henry (given name), including lists of people and fictional characters

* Henry (surname)

* Henry, a stage name of François-Louis Henry (1786–1855), French baritone

Arts and entertainmen ...

was present and moved quickly to secure the throne before the return of his elder brother Robert, Duke of Normandy, from the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

. Henry invited Anselm to return, pledging in his letter to submit himself to the archbishop's counsel. The cleric's support of Robert would have caused great trouble but Anselm returned before establishing any other terms than those offered by Henry. Once in England, Anselm was ordered by Henry to do homage for his Canterbury estates and to receive his investiture by ring

(The) Ring(s) may refer to:

* Ring (jewellery), a round band, usually made of metal, worn as ornamental jewelry

* To make a sound with a bell, and the sound made by a bell

Arts, entertainment, and media Film and TV

* ''The Ring'' (franchise), a ...

and crozier

A crozier or crosier (also known as a paterissa, pastoral staff, or bishop's staff) is a stylized staff that is a symbol of the governing office of a bishop or abbot and is carried by high-ranking prelates of Roman Catholic, Eastern Catholi ...

anew. Despite having done so under William, the bishop now refused to violate canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

. Henry for his part refused to relinquish a right possessed by his predecessors and even sent an embassy to Pope Paschal II to present his case. Paschal reaffirmed Urban's bans to that mission and the one that followed it.

Meanwhile, Anselm publicly supported Henry against the claims and threatened invasion of his brother Robert Curthose

Robert Curthose ( – February 1134, ), the eldest son of William the Conqueror, was Duke of Normandy as Robert II from 1087 to 1106.

Robert was also an unsuccessful pretender to the throne of the Kingdom of England. The epithet "Curthose" ...

. Anselm wooed wavering barons to the king's cause, emphasizing the religious nature of their oaths and duty of loyalty; he supported the deposition of Ranulf Flambard

Ranulf Flambard ( c. 1060 – 5 September 1128) was a medieval Norman Bishop of Durham and an influential government official of King William Rufus of England. Ranulf was the son of a priest of Bayeux, Normandy, and his nickname Flamba ...

, the disloyal new bishop of Durham

The bishop of Durham is head of the diocese of Durham in the province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler (bishop), Paul Butler was the most recent bishop of Durham u ...

; and he threatened Robert with excommunication. The lack of popular support greeting his invasion near Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

compelled Robert to accept the Treaty of Alton instead, renouncing his claims for an annual payment of 3000 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks

A collective trademark, collective trade mark, or collective mark is a trademark owned by an organization (such ...

.

Anselm held a council at Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament of the United King ...

which found that Henry's beloved Matilda had not technically become a nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service and contemplation, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 5 ...

and was thus eligible to wed and become queen. On Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in many Western Christian liturgical calendars on 29 Se ...

in 1102, Anselm was finally able to convene a general church council at London, establishing the Gregorian Reform

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–1080, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be na ...

within England. The council prohibited marriage, concubinage

Concubinage is an interpersonal relationship, interpersonal and Intimate relationship, sexual relationship between two people in which the couple does not want to, or cannot, enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarde ...

, and drunkenness to all those in holy orders, condemned sodomy

Sodomy (), also called buggery in British English, principally refers to either anal sex (but occasionally also oral sex) between people, or any Human sexual activity, sexual activity between a human and another animal (Zoophilia, bestiality). I ...

and simony

Simony () is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus, who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to imp ...

, and regulated clerical dress

Clerical clothing is non-liturgical clothing worn exclusively by clergy. It is distinct from vestments in that it is not reserved specifically for use in the liturgy. Practices vary: clerical clothing is sometimes worn under vestments, and someti ...

. Anselm also obtained a resolution against the British slave trade. Henry supported Anselm's reforms and his authority over the English Church but continued to assert his own authority over Anselm. Upon their return, the three bishops he had dispatched on his second delegation to the pope claimed—in defiance of Paschal's sealed letter to Anselm, his public acts, and the testimony of the two monks who had accompanied them—that the pontiff had been receptive to Henry's counsel and secretly approved of Anselm's submission to the crown. In 1103, then, Anselm consented to journey himself to Rome, along with the king's envoy William Warelwast

William Warelwast (died 1137) was a medieval Norman cleric and Bishop of Exeter in England. Warelwast was a native of Normandy, but little is known about his background before 1087, when he appears as a royal clerk for King William II. Most o ...

. Anselm supposedly travelled in order to argue the king's case for a dispensation but, in response to this third mission, Paschal fully excommunicated the bishops who had accepted investment from Henry, though sparing the king himself.

Second exile

After this ruling, Anselm received a letter forbidding his return and withdrew to Lyon to await Paschal's response. On 26 March 1105, Paschal again excommunicated prelates who had accepted investment from Henry and the advisors responsible, this time including Robert de Beaumont, Henry's chief advisor. He further finally threatened Henry with the same; in April, Anselm sent messages to the king directly and through his sister Adela expressing his own willingness to excommunicate Henry. This was probably a negotiation tactic but it came at a critical period in Henry's reign and it worked: a meeting was arranged and a compromise concluded atL'Aigle

L'Aigle is a commune in the Orne department in Normandy in northwestern France. Before 1961, the commune was known as ''Laigle''. According to Orderic Vitalis, the nest of an eagle (''aigle'' in French) was discovered during the construction ...

on 22 July 1105. Henry would forsake lay investiture if Anselm obtained Paschal's permission for clerics to do homage for their lands; Henry's bishops' and counsellors' excommunications were to be lifted provided they advise him to obey the papacy (Anselm performed this act on his own authority and later had to answer for it to Paschal); the revenues of Canterbury would be returned to the archbishop; and priests would no longer be permitted to marry. Anselm insisted on the agreement's ratification by the pope before he would consent to return to England, but wrote to Paschal in favour of the deal, arguing that Henry's forsaking of lay investiture was a greater victory than the matter of homage. On 23 March 1106, Paschal wrote Anselm accepting the terms established at L'Aigle, although both clerics saw this as a temporary compromise and intended to continue pressing for reforms, including the ending of homage to lay authorities.

Even after this, Anselm refused to return to England. Henry travelled to Bec and met with him on 15 August 1106. Henry was forced to make further concessions. He restored to Canterbury all the churches that had been seized by William or during Anselm's exile, promising that nothing more would be taken from them and even providing Anselm with a security payment. Henry had initially taxed married clergy and, when their situation had been outlawed, had made up the lost revenue by controversially extending the tax over all Churchmen. He now agreed that any prelate who had paid this would be exempt from taxation for three years. These compromises on Henry's part strengthened the rights of the church against the king. Anselm returned to England before the new year.

Final years

In 1107, the Concordat of London formalized the agreements between the king and archbishop, Henry formally renounced the right of English kings to invest the bishops of the church. The remaining two years of Anselm's life were spent in the duties of his archbishopric. He succeeded in getting Paschal to send the pallium for the

In 1107, the Concordat of London formalized the agreements between the king and archbishop, Henry formally renounced the right of English kings to invest the bishops of the church. The remaining two years of Anselm's life were spent in the duties of his archbishopric. He succeeded in getting Paschal to send the pallium for the archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

to Canterbury so that future archbishops-elect would have to profess obedience before receiving it. The incumbent archbishop Thomas II had received his own pallium directly and insisted on York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

's independence. From his deathbed, Anselm anathema

The word anathema has two main meanings. One is to describe that something or someone is being hated or avoided. The other refers to a formal excommunication by a Christian denomination, church. These meanings come from the New Testament, where a ...

tized all who failed to recognize Canterbury's primacy over all the English Church. This ultimately forced Henry to order Thomas to confess his obedience to Anselm's successor. On his deathbed, he announced himself content, except that he had a treatise in mind on the origin of the soul

The soul is the purported Mind–body dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

and did not know, once he was gone, if another was likely to compose it.

He died on Holy Wednesday

In Christianity, Holy Wednesday commemorates the Bargain of Judas as a clandestine spy among the disciples. It is also called Spy Wednesday, or Good Wednesday (in Western Christianity), and Great and Holy Wednesday (in Eastern Christianity).

In ...

, 21 April 1109. His remains were translated to Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the spiritual leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christianity, Ch ...

and laid at the head of Lanfranc at his initial resting place to the south of the Altar of the Holy Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, three ...

(now St Thomas's Chapel). During the church's reconstruction after the disastrous fire of the 1170s, his remains were relocated, although it is now uncertain where.

On 23 December 1752, Archbishop Herring was contacted by Count Perron, the Sardinian ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or so ...

, on behalf of King Charles Emmanuel, who requested permission to translate Anselm's relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains or personal effects of a saint or other person preserved for the purpose of veneration as a tangible memorial. Reli ...

s to Italy. (Charles had been duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobi ...

of Aosta

Aosta ( , , ; ; , or ; or ) is the principal city of the Aosta Valley, a bilingual Regions of Italy, region in the Italy, Italian Alps, north-northwest of Turin. It is situated near the Italian entrance of the Mont Blanc Tunnel and the G ...

during his minority.) Herring ordered his dean to look into the matter, saying that while "the parting with the rotten Remains of a Rebel to his King, a Slave to the Popedom, and an Enemy to the married Clergy (all this Anselm was)" would be no great matter, he likewise "should make no Conscience of palming on the Simpletons any other old Bishop with the Name of Anselm". The ambassador insisted on witnessing the excavation, however, and resistance on the part of the prebendaries seems to have quieted the matter. They considered the state of the cathedral's crypts would have offended the sensibilities of a Catholic and that it was probable that Anselm had been removed to near the altar of SS Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a su ...

and Paul

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo ...

, whose side chapel to the right (i.e., south) of the high altar took Anselm's name following his canonization. At that time, his relics would presumably have been placed in a shrine

A shrine ( "case or chest for books or papers"; Old French: ''escrin'' "box or case") is a sacred space">-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ...: ''escri ...

and its contents "disposed of" during the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

. The ambassador's own investigation was of the opinion that Anselm's body had been confused with Archbishop Theobald's and likely remained entombed near the altar of the Virgin Mary

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

, but in the uncertainty nothing further seems to have been done then or when inquiries were renewed in 1841.

Writings

Anselm has been called "the most luminous and penetrating intellect between St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas" and "the father ofscholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

", Scotus Erigena having employed more mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute (philosophy), Absolute, but may refer to any kind of Religious ecstasy, ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or Spirituality, spiritual meani ...

in his arguments. Anselm's works are considered philosophical as well as theological since they endeavour to render Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

tenets of faith, traditionally taken as a revealed truth, as a rational

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reason. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do, or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ...

system. Anselm also studiously analyzed the language used in his subjects, carefully distinguishing the meaning of the terms employed from the verbal forms, which he found at times wholly inadequate. His worldview was broadly Neoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

, as it was reconciled with Christianity in the works of St Augustine and Pseudo-Dionysius

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (or Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite) was a Greek author, Christian theologian and Neoplatonic philosopher of the late 5th to early 6th century, who wrote a set of works known as the ''Corpus Areopagiticum'' or ...

, with his understanding of Aristotelian logic

In logic and formal semantics, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly b ...

gathered from the works of Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known simply as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480–524 AD), was a Roman Roman Senate, senator, Roman consul, consul, ''magister officiorum'', polymath, historian, and philosopher of the Early Middl ...

. He or the thinkers in northern France who shortly followed him—including Abelard

Peter Abelard (12 February 1079 – 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, teacher, musician, composer, and poet. This source has a detailed description of his philosophical work.

In philo ...

, William of Conches, and Gilbert of Poitiers—inaugurated "one of the most brilliant periods of Western philosophy

Western philosophy refers to the Philosophy, philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre ...

", innovating logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, semantics

Semantics is the study of linguistic Meaning (philosophy), meaning. It examines what meaning is, how words get their meaning, and how the meaning of a complex expression depends on its parts. Part of this process involves the distinction betwee ...

, ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

, and other areas of philosophical theology

Philosophical theology is both a branch and form of theology in which philosophical methods are used in developing or analyzing theological concepts. It therefore includes natural theology as well as philosophical treatments of orthodox and het ...

.