Sponges or sea sponges are primarily

marine invertebrates of the

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a

basal clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

and a

sister taxon of the

diploblasts.

They are

sessile filter feeders that are bound to the

seabed, and are one of the most ancient members of

macrobenthos, with many historical species being important

reef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral, or similar relatively stable material lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic component, abiotic (non-living) processes such as deposition (geol ...

-building organisms.

Sponges are

multicellular organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell (biology), cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, Embryophyte, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organism ...

s consisting of jelly-like

mesohyl sandwiched between two thin layers of

cells, and usually have tube-like bodies full of pores and channels that allow water to circulate through them. They have unspecialized cells that can

transform into other types and that often migrate between the main cell layers and the mesohyl in the process. They do not have complex

nervous,

or

circulatory system

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart ...

s. Instead, most rely on maintaining a constant water flow through their bodies to obtain food and

oxygen and to remove wastes, usually via

flagella movements of the so-called "

collar cells".

Sponges are believed to have been the first

outgroup to branch off the

evolutionary tree from the

last common ancestor of all animals,

with fossil evidence of primitive sponges such as ''

Otavia

''Otavia antiqua'' is an ancient sponge-like multicellular organism found in the Otavi Group (the generic name being the namesake) in the Etosha National Park, Namibia. It is claimed to be the oldest animal fossil, being found in rock aged ...

'' from as early as the

Tonian period (around 800

Mya). The branch of

zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

that studies sponges is spongiology.

Etymology

The term ''sponge'' derives from the

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

word . The

scientific name

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin gramm ...

''Porifera'' is a

neuter plural

In many languages, a plural (sometimes list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated as pl., pl, , or ), is one of the values of the grammatical number, grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than ...

of the

Modern Latin term ''porifer'', which comes from the

roots ''porus'' meaning "pore, opening", and ''-fer'' meaning "bearing or carrying".

Overview

Sponges are similar to other animals in that they are

multicellular,

heterotrophic, lack

cell walls and produce

sperm cells. Unlike other animals, they lack true

tissues and

organs. Some of them are radially symmetrical, but most are asymmetrical. The shapes of their bodies are adapted for maximal efficiency of water flow through the central cavity, where the water deposits nutrients and then leaves through a hole called the

osculum. The

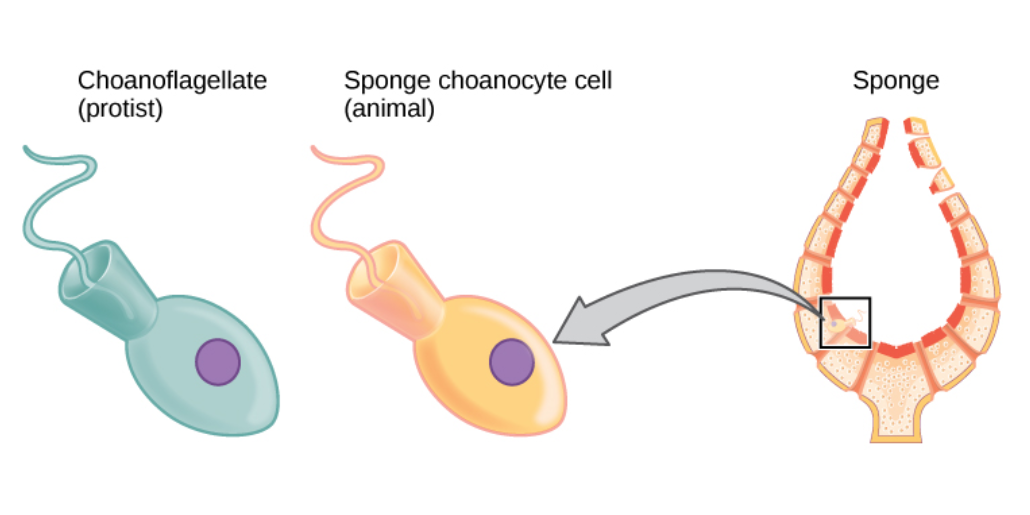

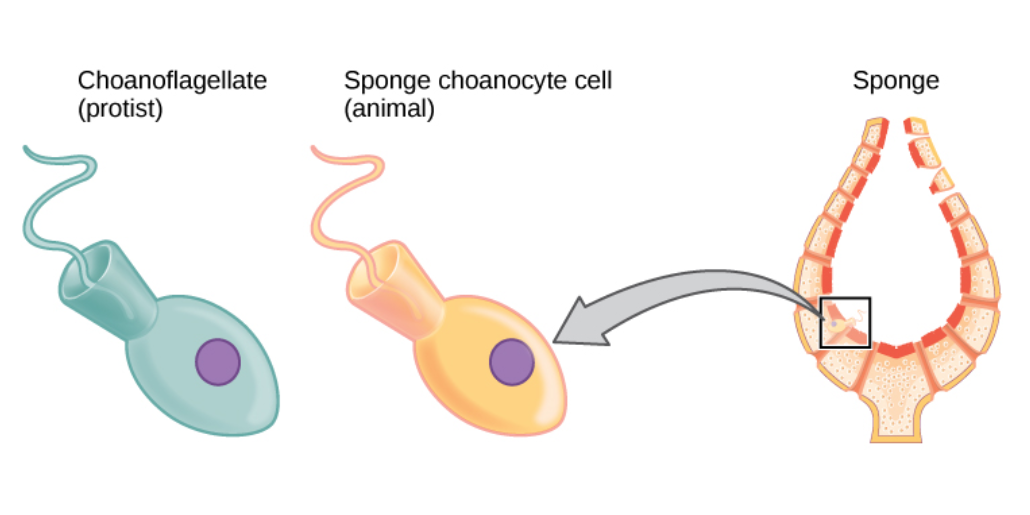

single-celled choanoflagellates resemble the

choanocyte cells of sponges which are used to drive their water flow systems and capture most of their food. This along with phylogenetic studies of ribosomal molecules have been used as morphological evidence to suggest sponges are the sister group to the rest of animals.

A great majority are marine (salt-water) species, ranging in habitat from tidal zones to depths exceeding , though there are freshwater species. All adult sponges are

sessile, meaning that they attach to an underwater surface and remain fixed in place (i.e., do not travel). While in their

larval stage of life, they are

motile.

Many sponges have internal skeletons of spicules (skeletal-like fragments of

calcium carbonate or

silicon dioxide

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundan ...

), and/or

spongin (a modified type of collagen protein).

An internal gelatinous

matrix called mesohyl functions as an

endoskeleton, and it is the only skeleton in soft sponges that encrust such hard surfaces as rocks. More commonly, the mesohyl is stiffened by

mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

spicules, by spongin fibers, or both. Most sponges (over 90% of all known species) are

demosponge

Demosponges or common sponges are sponges of the class Demospongiae (from + ), the most diverse group in the phylum Porifera which include greater than 90% of all extant sponges with nearly 8,800 species

A species () is often de ...

s, which have the widest range of habitats (including all freshwater ones); they use spongin,

silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

spicules, or both, and some species have calcium carbonate

exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

s.

Calcareans have calcium carbonate spicules and, in some species, calcium carbonate exoskeletons; they are restricted to relatively shallow marine waters where production of calcium carbonate is easiest.

The fragile

hexactinellids or glass sponges use "

scaffolding" of silica spicules and are restricted to polar regions or ocean depths where predators are rare. Fossils of all of these types have been found in rocks dated from . In addition

Archaeocyathids, whose fossils are common in rocks from , are now regarded as a type of sponge. The smallest class of extant sponges are

homoscleromorphs, which either have calcium carbonate spicules like the calcereans or are aspiculate, and found in shaded marine environments like caves and overhangs.

Although most of the approximately 5,000–10,000 known species of sponges feed on

bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and other microscopic food in the water, some host

photosynthesizing microorganisms as

endosymbiont

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

s, and these alliances often produce more food and oxygen than they consume. A few species of sponges that live in food-poor environments have evolved as

carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they ar ...

s that prey mainly on small

crustaceans.

Most sponges reproduce

sexually, but they can also reproduce asexually. Sexually reproducing species release

sperm

Sperm (: sperm or sperms) is the male reproductive Cell (biology), cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm ...

cells into the water to fertilize

ova released or retained by its mate or "mother"; the fertilized eggs develop into

larvae which swim off in search of places to settle.

Sponges are known for regenerating from fragments that are broken off, although this only works if the fragments include the right types of cells. Some species reproduce by budding. When environmental conditions become less hospitable to the sponges, for example as temperatures drop, many freshwater species and a few marine ones produce

gemmules, "survival pods" of unspecialized cells that remain dormant until conditions improve; they then either form completely new sponges or recolonize the skeletons of their parents.

The few species of demosponge that have entirely soft fibrous skeletons with no hard elements have been used by humans over thousands of years for several purposes, including as padding and as cleaning tools. By the 1950s, though, these had been

overfished so heavily that the industry almost collapsed, and most sponge-like materials are now synthetic. Sponges and their microscopic endosymbionts are now being researched as possible sources of medicines for treating a wide range of diseases.

Dolphins have been observed using sponges as tools while

foraging.

Distinguishing features

Sponges constitute the

phylum Porifera, and have been defined as

sessile metazoans (multicelled immobile animals) that have water intake and outlet openings connected by chambers lined with

choanocytes, cells with whip-like flagella.

However, a few carnivorous sponges have lost these water flow systems and the choanocytes.

All known living sponges can remold their bodies, as most types of their cells can move within their bodies and a few can change from one type to another.

Even if a few sponges are able to produce mucus – which acts as a microbial barrier in all other animals – no sponge with the ability to secrete a functional mucus layer has been recorded. Without such a mucus layer their living tissue is covered by a layer of microbial symbionts, which can contribute up to 40–50% of the sponge wet mass. This inability to prevent microbes from penetrating their porous tissue could be a major reason why they have never evolved a more complex anatomy.

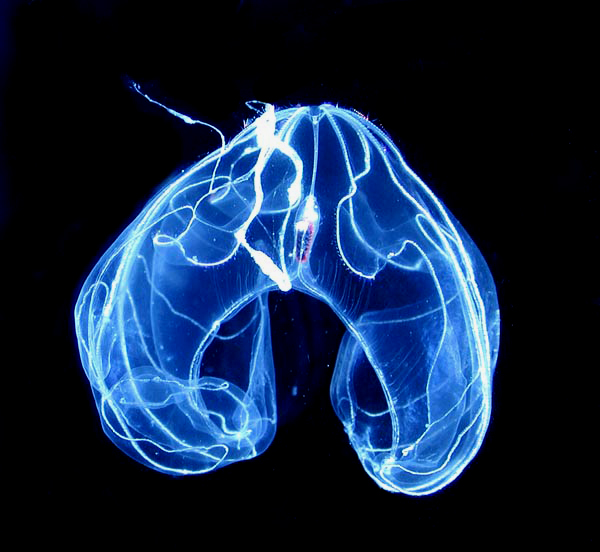

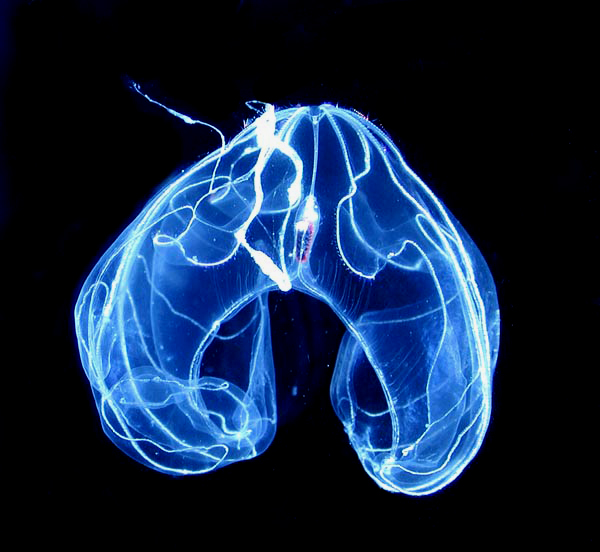

Like

cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

ns (jellyfish, etc.) and

ctenophores (comb jellies), and unlike all other known metazoans, sponges' bodies consist of a non-living jelly-like mass (

mesohyl) sandwiched between two main layers of cells.

Cnidarians and ctenophores have simple nervous systems, and their cell layers are bound by internal connections and by being mounted on a basement membrane (thin fibrous mat, also known as "

basal lamina").

Sponges do not have a nervous system similar to that of vertebrates but may have one that is quite different.

Their middle jelly-like layers have large and varied populations of cells, and some types of cells in their outer layers may move into the middle layer and change their functions.

Basic structure

Cell types

A sponge's body is hollow and is held in shape by the

mesohyl, a jelly-like substance made mainly of

collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

and reinforced by a dense network of fibers also made of collagen. 18 distinct cell types have been identified. The inner surface is covered with

choanocytes, cells with cylindrical or conical collars surrounding one

flagellum per choanocyte. The wave-like motion of the whip-like flagella drives water through the sponge's body. All sponges have ostia, channels leading to the interior through the mesohyl, and in most sponges these are controlled by tube-like

porocytes that form closable inlet valves.

Pinacocytes, plate-like cells, form a single-layered external skin over all other parts of the mesohyl that are not covered by choanocytes, and the pinacocytes also digest food particles that are too large to enter the ostia,

while those at the base of the animal are responsible for anchoring it.

Other types of cells live and move within the mesohyl:

*

Lophocytes are

amoeba-like cells that move slowly through the mesohyl and secrete collagen fibres.

*

Collencytes are another type of collagen-producing cell.

*

Rhabdiferous cells secrete

polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s that also form part of the mesohyl.

*

Oocytes and

spermatocytes are reproductive cells.

*

Sclerocytes secrete the mineralized

spicules ("little spines") that form the

skeletons of many sponges and in some species provide some defense against predators.

* In addition to or instead of sclerocytes,

demosponge

Demosponges or common sponges are sponges of the class Demospongiae (from + ), the most diverse group in the phylum Porifera which include greater than 90% of all extant sponges with nearly 8,800 species

A species () is often de ...

s have

spongocytes that secrete a form of collagen that

polymer

A polymer () is a chemical substance, substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeat unit, repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers. Due to their br ...

izes into

spongin, a thick fibrous material that stiffens the mesohyl.

*

Myocyte

A muscle cell, also known as a myocyte, is a mature contractile Cell (biology), cell in the muscle of an animal. In humans and other vertebrates there are three types: skeletal muscle, skeletal, smooth muscle, smooth, and Cardiac muscle, cardiac ...

s ("muscle cells") conduct signals and cause parts of the animal to contract.

* "Grey cells" act as sponges' equivalent of an

immune system.

*

Archaeocytes (or

amoebocytes) are

amoeba-like cells that are

totipotent, in other words, each is capable of transformation into any other type of cell. They also have important roles in feeding and in clearing debris that block the ostia.

Many larval sponges possess neuron-less

eyes that are based on

cryptochromes. They mediate phototaxic behavior.

Glass sponges present a distinctive variation on this basic plan. Their spicules, which are made of

silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

, form a

scaffolding-like framework between whose rods the living tissue is suspended like a

cobweb that contains most of the cell types.

This tissue is a

syncytium that in some ways behaves like many cells that share a single external

membrane, and in others like a single cell with multiple

nuclei.

Water flow and body structures

Most sponges work rather like

chimneys: they take in water at the bottom and eject it from the

osculum at the top. Since ambient currents are faster at the top, the suction effect that they produce by

Bernoulli's principle does some of the work for free. Sponges can control the water flow by various combinations of wholly or partially closing the osculum and ostia (the intake pores) and varying the beat of the flagella, and may shut it down if there is a lot of sand or silt in the water.

Although the layers of

pinacocytes and

choanocytes resemble the

epithelia of more complex animals, they are not bound tightly by cell-to-cell connections or a basal lamina (thin fibrous sheet underneath). The flexibility of these layers and re-modeling of the mesohyl by lophocytes allow the animals to adjust their shapes throughout their lives to take maximum advantage of local water currents.

The simplest body structure in sponges is a tube or vase shape known as "asconoid", but this severely limits the size of the animal. The body structure is characterized by a stalk-like spongocoel surrounded by a single layer of choanocytes. If it is simply scaled up, the ratio of its volume to surface area increases, because surface increases as the square of length or width while volume increases proportionally to the cube. The amount of tissue that needs food and

oxygen is determined by the volume, but the pumping capacity that supplies food and oxygen depends on the area covered by choanocytes. Asconoid sponges seldom exceed in diameter.

Some sponges overcome this limitation by adopting the "syconoid" structure, in which the body wall is

pleated. The inner pockets of the pleats are lined with choanocytes, which connect to the outer pockets of the pleats by ostia. This increase in the number of choanocytes and hence in pumping capacity enables syconoid sponges to grow up to a few centimeters in diameter.

The "leuconoid" pattern boosts pumping capacity further by filling the interior almost completely with mesohyl that contains a network of chambers lined with choanocytes and connected to each other and to the water intakes and outlet by tubes. Leuconid sponges grow to over in diameter, and the fact that growth in any direction increases the number of choanocyte chambers enables them to take a wider range of forms, for example, "encrusting" sponges whose shapes follow those of the surfaces to which they attach. All freshwater and most shallow-water marine sponges have leuconid bodies. The networks of water passages in

glass sponges are similar to the leuconid structure.

In all three types of structure, the cross-section area of the choanocyte-lined regions is much greater than that of the intake and outlet channels. This makes the flow slower near the choanocytes and thus makes it easier for them to trap food particles.

For example, in ''

Leuconia'', a small leuconoid sponge about tall and in diameter, water enters each of more than 80,000 intake canals at 6 cm per ''minute''. However, because ''Leuconia'' has more than 2 million flagellated chambers whose combined diameter is much greater than that of the canals, water flow through chambers slows to 3.6 cm per ''hour'', making it easy for choanocytes to capture food. All the water is expelled through a single

osculum at about 8.5 cm per ''second'', fast enough to carry waste products some distance away.

Skeleton

In zoology, a

skeleton is any fairly rigid structure of an animal, irrespective of whether it has joints and irrespective of whether it is

biomineralized. The mesohyl functions as an

endoskeleton in most sponges, and is the only skeleton in soft sponges that encrust hard surfaces such as rocks. More commonly the mesohyl is stiffened by mineral

spicules, by spongin fibers or both. Spicules, which are present in most but not all species, may be made of

silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

or calcium carbonate, and vary in shape from simple rods to three-dimensional "stars" with up to six rays. Spicules are produced by

sclerocyte cells,

and may be separate, connected by joints, or fused.

Some sponges also secrete

exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

s that lie completely outside their organic components. For example,

sclerosponges ("hard sponges") have massive calcium carbonate exoskeletons over which the organic matter forms a thin layer with

choanocyte chambers in pits in the mineral. These exoskeletons are secreted by the

pinacocytes that form the animals' skins.

Vital functions

Movement

Although adult sponges are fundamentally

sessile animals, some marine and freshwater species can move across the sea bed at speeds of per day, as a result of

amoeba-like movements of

pinacocytes and other cells. A few species can contract their whole bodies, and many can close their

oscula and

ostia. Juveniles drift or swim freely, while adults are stationary.

Respiration, feeding and excretion

Sponges do not have distinct

circulatory,

respiratory,

digestive, and

excretory systems – instead, the water flow system supports all these functions. They

filter food particles out of the water flowing through them. Particles larger than 50 micrometers cannot enter the

ostia and

pinacocytes consume them by

phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell (biology), cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs ph ...

(engulfing and intracellular digestion). Particles from 0.5 μm to 50 μm are trapped in the ostia, which taper from the outer to inner ends. These particles are consumed by pinacocytes or by

archaeocytes which partially extrude themselves through the walls of the ostia. Bacteria-sized particles, below 0.5 micrometers, pass through the ostia and are caught and consumed by

choanocytes.

Since the smallest particles are by far the most common, choanocytes typically capture 80% of a sponge's food supply.

Archaeocytes transport food packaged in

vesicles from cells that directly digest food to those that do not. At least one species of sponge has internal fibers that function as tracks for use by nutrient-carrying archaeocytes,

and these tracks also move inert objects.

It used to be claimed that

glass sponges could live on nutrients dissolved in sea water and were very averse to silt.

However, a study in 2007 found no evidence of this and concluded that they extract bacteria and other micro-organisms from water very efficiently (about 79%) and process suspended sediment grains to extract such prey. Collar bodies digest food and distribute it wrapped in vesicles that are transported by

dynein "motor" molecules along bundles of

microtubules that run throughout the

syncytium.

Sponges' cells absorb oxygen by

diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical p ...

from water into cells as water flows through body, into which

carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

and other soluble waste products such as

ammonia also diffuse. Archeocytes remove mineral particles that threaten to block the ostia, transport them through the mesohyl and generally dump them into the outgoing water current, although some species incorporate them into their skeletons.

Carnivorous sponges

In waters where the supply of food particles is very poor, some species prey on

crustaceans and other small animals. As of 2014, a total of 137 species had been discovered. Most belong to the

family Cladorhizidae, but a few members of the

Guitarridae and

Esperiopsidae are also carnivores.

In most cases, little is known about how they actually capture prey, although some species are thought to use either sticky threads or hooked

spicules.

Most carnivorous sponges live in deep waters, up to ,

and the development of deep-ocean exploration techniques is expected to lead to the discovery of several more.

However, one species has been found in

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

caves at depths of , alongside the more usual

filter-feeding sponges. The cave-dwelling predators capture crustaceans under long by entangling them with fine threads, digest them by enveloping them with further threads over the course of a few days, and then return to their normal shape; there is no evidence that they use

venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a sti ...

.

Most known carnivorous sponges have completely lost the water flow system and

choanocytes. However, the

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

''

Chondrocladia'' uses a highly modified water flow system to inflate balloon-like structures that are used for capturing prey.

Endosymbionts

Freshwater sponges often host

green algae

The green algae (: green alga) are a group of chlorophyll-containing autotrophic eukaryotes consisting of the phylum Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister group that contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/ Streptophyta. The land plants ...

as

endosymbiont

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

s within

archaeocytes and other cells and benefit from nutrients produced by the algae. Many marine species host other

photosynthesizing organisms, most commonly

cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

but in some cases

dinoflagellates. Symbiotic cyanobacteria may form a third of the total mass of living tissue in some sponges, and some sponges gain 48% to 80% of their energy supply from these micro-organisms.

In 2008, a

University of Stuttgart team reported that spicules made of

silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

conduct light into the

mesohyl, where the photosynthesizing endosymbionts live. Sponges that host photosynthesizing organisms are most common in waters with relatively poor supplies of food particles and often have leafy shapes that maximize the amount of sunlight they collect.

A recently discovered carnivorous sponge that lives near

hydrothermal vents hosts

methane-eating bacteria and digests some of them.

"Immune" system

Sponges do not have the complex

immune systems of most other animals. However, they reject

grafts from other species but accept them from other members of their own species. In a few marine species, gray cells play the leading role in rejection of foreign material. When invaded, they produce a chemical that stops movement of other cells in the affected area, thus preventing the intruder from using the sponge's internal transport systems. If the intrusion persists, the grey cells concentrate in the area and release toxins that kill all cells in the area. The "immune" system can stay in this activated state for up to three weeks.

Reproduction

Asexual

Sponges have three

asexual methods of reproduction: after fragmentation, by

budding, and by producing

gemmules. Fragments of sponges may be detached by currents or waves. They use the mobility of their

pinacocytes and

choanocytes and reshaping of the

mesohyl to re-attach themselves to a suitable surface and then rebuild themselves as small but functional sponges over the course of several days. The same capabilities enable sponges that have been squeezed through a fine cloth to regenerate.

A sponge fragment can only regenerate if it contains both

collencytes to produce

mesohyl and

archeocytes to produce all the other cell types.

A very few species reproduce by budding.

Gemmules are "survival pods" which a few marine sponges and many freshwater species produce by the thousands when dying and which some, mainly freshwater species, regularly produce in autumn.

Spongocytes make gemmules by wrapping shells of spongin, often reinforced with spicules, round clusters of

archeocytes that are full of nutrients.

Freshwater gemmules may also include photosynthesizing symbionts.

The gemmules then become dormant, and in this state can survive cold, drying out, lack of oxygen and extreme variations in

salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

.

Freshwater gemmules often do not revive until the temperature drops, stays cold for a few months and then reaches a near-"normal" level.

When a gemmule germinates, the archeocytes round the outside of the cluster transform into

pinacocytes, a membrane over a pore in the shell bursts, the cluster of cells slowly emerges, and most of the remaining archeocytes transform into other cell types needed to make a functioning sponge. Gemmules from the same species but different individuals can join forces to form one sponge.

Some gemmules are retained within the parent sponge, and in spring it can be difficult to tell whether an old sponge has revived or been "recolonized" by its own gemmules.

Sexual

Most sponges are

hermaphrodites (function as both sexes simultaneously), although sponges have no

gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a Heterocrine gland, mixed gland and sex organ that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gon ...

s (reproductive organs). Sperm are produced by

choanocytes or entire choanocyte chambers that sink into the

mesohyl and form spermatic

cysts while eggs are formed by transformation of

archeocytes, or of choanocytes in some species. Each egg generally acquires a

yolk

Among animals which produce eggs, the yolk (; also known as the vitellus) is the nutrient-bearing portion of the egg whose primary function is to supply food for the development of the embryo. Some types of egg contain no yolk, for example bec ...

by consuming "nurse cells". During spawning, sperm burst out of their cysts and are expelled via the

osculum. If they contact another sponge of the same species, the water flow carries them to choanocytes that engulf them but, instead of digesting them, metamorphose to an

ameboid form and carry the sperm through the mesohyl to eggs, which in most cases engulf the carrier and its cargo.

A few species release fertilized eggs into the water, but most retain the eggs until they hatch. By retaining the eggs, the parents can transfer symbiotic microorganisms directly to their offspring through

vertical transmission, while the species who release their eggs into the water has to acquire symbionts horizontally (a combination of both is probably most common, where larvae with vertically transmitted symbionts also acquire others horizontally). There are four types of larvae, but all are lecithotrophic (non-feeding) balls of cells with an outer layer of cells whose

flagella or

cilia enable the larvae to move. After swimming for a few days the larvae sink and crawl until they find a place to settle. Most of the cells transform into archeocytes and then into the types appropriate for their locations in a miniature adult sponge.

embryos start by dividing into separate cells, but once 32 cells have formed they rapidly transform into larvae that externally are

ovoid with a band of

cilia round the middle that they use for movement, but internally have the typical glass sponge structure of spicules with a cobweb-like main

syncitium draped around and between them and

choanosyncytia with multiple collar bodies in the center. The larvae then leave their parents' bodies.

Meiosis

The cytological progression of porifera

oogenesis and

spermatogenesis (

gametogenesis) is very similar to that of other metazoa.

Most of the genes from the classic set of

meiotic genes, including genes for DNA recombination and double-strand break repair, that are conserved in

eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s are expressed in the sponges (e.g. ''

Geodia hentscheli'' and ''Geodia phlegraei'').

Since porifera are considered to be the earliest divergent animals, these findings indicate that the basic toolkit of meiosis including capabilities for recombination and DNA repair were present early in eukaryote evolution.

Life cycle

Sponges in

temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ran ...

regions live for at most a few years, but some

tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

species and perhaps some deep-ocean ones may live for 200 years or more. Some calcified

demosponge

Demosponges or common sponges are sponges of the class Demospongiae (from + ), the most diverse group in the phylum Porifera which include greater than 90% of all extant sponges with nearly 8,800 species

A species () is often de ...

s grow by only per year and, if that rate is constant, specimens wide must be about 5,000 years old. Some sponges start sexual reproduction when only a few weeks old, while others wait until they are several years old.

Coordination of activities

Adult sponges lack

neurons or any other kind of

nervous tissue. However, most species have the ability to perform movements that are coordinated all over their bodies, mainly contractions of the

pinacocytes, squeezing the water channels and thus expelling excess sediment and other substances that may cause blockages. Some species can contract the

osculum independently of the rest of the body. Sponges may also contract in order to reduce the area that is vulnerable to attack by predators. In cases where two sponges are fused, for example if there is a large but still unseparated bud, these contraction waves slowly become coordinated in both of the "

Siamese twins". The coordinating mechanism is unknown, but may involve chemicals similar to

neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a Chemical synapse, synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotra ...

s. However,

glass sponges rapidly transmit electrical impulses through all parts of the

syncytium, and use this to halt the motion of their

flagella if the incoming water contains toxins or excessive sediment.

Myocyte

A muscle cell, also known as a myocyte, is a mature contractile Cell (biology), cell in the muscle of an animal. In humans and other vertebrates there are three types: skeletal muscle, skeletal, smooth muscle, smooth, and Cardiac muscle, cardiac ...

s are thought to be responsible for closing the osculum and for transmitting signals between different parts of the body.

Sponges contain

gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s very similar to those that contain the "recipe" for the post-

synaptic density, an important signal-receiving structure in the neurons of all other animals. However, in sponges these genes are only activated in "flask cells" that appear only in larvae and may provide some sensory capability while the larvae are swimming. This raises questions about whether flask cells represent the predecessors of true neurons or are evidence that sponges' ancestors had true neurons but lost them as they adapted to a sessile lifestyle.

Ecology

Habitats

Sponges are worldwide in their distribution, living in a wide range of ocean habitats, from the polar regions to the tropics.

Most live in quiet, clear waters, because sediment stirred up by waves or currents would block their pores, making it difficult for them to feed and breathe.

The greatest numbers of sponges are usually found on firm surfaces such as rocks, but some sponges can attach themselves to soft sediment by means of a root-like base.

Sponges are more abundant but less diverse in temperate waters than in tropical waters, possibly because organisms that prey on sponges are more abundant in tropical waters.

Glass sponges are the most common in polar waters and in the depths of temperate and tropical seas, as their very porous construction enables them to extract food from these resource-poor waters with the minimum of effort.

Demosponge

Demosponges or common sponges are sponges of the class Demospongiae (from + ), the most diverse group in the phylum Porifera which include greater than 90% of all extant sponges with nearly 8,800 species

A species () is often de ...

s and

calcareous sponges are abundant and diverse in shallower non-polar waters.

The different

classes of sponge live in different ranges of habitat:

:

As primary producers

Sponges with

photosynthesizing endosymbiont

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

s produce up to three times more

oxygen than they consume, as well as more organic matter than they consume. Such contributions to their habitats' resources are significant along Australia's

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system, composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

but relatively minor in the Caribbean.

Defenses

Many sponges shed

spicules, forming a dense carpet several meters deep that keeps away

echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any animal of the phylum Echinodermata (), which includes starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers, as well as the sessile sea lilies or "stone lilies". While bilaterally symmetrical as ...

s which would otherwise prey on the sponges.

They also produce toxins that prevent other sessile organisms such as

bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary Colony (biology), colonies. Typically about long, they have a spe ...

ns or

sea squirts from growing on or near them, making sponges very effective competitors for living space. One of many examples includes

ageliferin, which has antibacterial action and causes biofilms to dissolve.

A few species, including the

Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

fire sponge ''

Tedania ignis'', cause a severe rash in humans who handle them.

Turtles and some fish feed mainly on sponges. It is often said that sponges produce

chemical defenses against such predators.

However, experiments have been unable to establish a relationship between the toxicity of chemicals produced by sponges and how they taste to fish, which would diminish the usefulness of chemical defenses as deterrents. Predation by fish may even help to spread sponges by detaching fragments.

However, some studies have shown fish showing a preference for non-chemically-defended sponges, and another study found that high levels of coral predation did predict the presence of chemically defended species.

Glass sponges produce no toxic chemicals, and live in very deep water where predators are rare.

Predation

Spongeflies, also known as spongillaflies (

Neuroptera,

Sisyridae), are specialist predators of freshwater sponges. The female lays her eggs on vegetation overhanging water. The larvae hatch and drop into the water where they seek out sponges to feed on. They use their elongated mouthparts to pierce the sponge and suck the fluids within. The larvae of some species cling to the surface of the sponge while others take refuge in the sponge's internal cavities. The fully grown larvae leave the water and spin a cocoon in which to pupate.

Bioerosion

The Caribbean chicken-liver sponge ''

Chondrilla nucula'' secretes toxins that kill coral

polyps, allowing the sponges to grow over the coral skeletons.

Others, especially in the family

Clionaidae, use corrosive substances secreted by their archeocytes to tunnel into rocks, corals and the shells of dead

mollusk

Mollusca is a phylum of protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum after Arthropoda. The ...

s.

Sponges may remove up to per year from reefs, creating visible notches just below low-tide level.

Diseases

Caribbean sponges of the genus ''

Aplysina'' suffer from

Aplysina red band syndrome. This causes ''Aplysina'' to develop one or more rust-colored bands, sometimes with adjacent bands of

necrotic tissue. These lesions may completely encircle branches of the sponge. The disease appears to be

contagious and impacts approximately ten percent of ''A. cauliformis'' on Bahamian reefs.

The rust-colored bands are caused by a

cyanobacterium, but it is unknown whether this organism actually causes the disease.

Collaboration with other organisms

In addition to hosting photosynthesizing endosymbionts,

sponges are noted for their wide range of collaborations with other organisms. The relatively large encrusting sponge ''

Lissodendoryx colombiensis'' is most common on rocky surfaces, but has extended its range into

seagrass meadow

A seagrass meadow or seagrass bed is an underwater ecosystem formed by seagrasses. Seagrasses are marine (saltwater) plants found in shallow coastal waters and in the brackish waters of estuaries. Seagrasses are flowering plants with stems and ...

s by letting itself be surrounded or overgrown by seagrass sponges, which are distasteful to the local

starfish

Starfish or sea stars are Star polygon, star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class (biology), class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to brittle star, ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to ...

and therefore protect ''Lissodendoryx'' against them; in return, the seagrass sponges get higher positions away from the sea-floor sediment.

Shrimps of the genus ''

Synalpheus'' form colonies in sponges, and each shrimp species inhabits a different sponge species, making ''Synalpheus'' one of the most diverse

crustacean genera. Specifically,

Synalpheus regalis utilizes the sponge not only as a food source, but also as a defense against other shrimp and predators. As many as 16,000 individuals inhabit a single

loggerhead sponge, feeding off the larger particles that collect on the sponge as it filters the ocean to feed itself. Other crustaceans such as hermit crabs commonly have a specific species of sponge, ''

Pseudospongosorites'', grow on them as both the sponge and crab occupy gastropod shells until the crab and sponge outgrow the shell, eventually resulting in the crab using the sponge's body as protection instead of the shell until the crab finds a suitable replacement shell.

Sponge loop

Most sponges are

detritivores which filter

organic debris particles and

microscopic life forms from ocean water. In particular, sponges occupy an important role as detritivores in

coral reef food webs by recycling detritus to higher

trophic levels.

The hypothesis has been made that coral reef sponges facilitate the transfer of coral-derived organic matter to their associated detritivores via the production of sponge detritus, as shown in the diagram. Several sponge species are able to convert coral-derived DOM into sponge detritus,

and transfer organic matter produced by corals further up the reef food web. Corals release organic matter as both dissolved and particulate mucus,

as well as cellular material such as expelled ''

Symbiodinium''.

Organic matter could be transferred from corals to sponges by all these pathways, but DOM likely makes up the largest fraction, as the majority (56 to 80%) of coral mucus dissolves in the water column,

and coral loss of fixed carbon due to expulsion of ''Symbiodinium'' is typically negligible (0.01%)

compared with mucus release (up to ~40%).

Coral-derived organic matter could also be indirectly transferred to sponges via bacteria, which can also consume coral mucus.

Sponge microbiome

Besides a one to one

symbiotic relationship, it is possible for a host to become symbiotic with a

microbial consortium, resulting in a diverse

sponge microbiome. Sponges are able to host a wide range of

microbial communities that can also be very specific. The microbial communities that form a symbiotic relationship with the sponge can amount to as much as 35% of the

biomass of its host.

The term for this specific symbiotic relationship, where a microbial consortia pairs with a host is called a

holobiotic relationship. The sponge as well as the microbial community associated with it will produce a large range of secondary

metabolites that help protect it against predators through mechanisms such as

chemical defense.

The sponge holobiont is an example of the concept of nested ecosystems. Environmental factors act at multiple scales to alter microbiome, holobiont, community, and ecosystem scale processes. Thus, factors that alter microbiome functioning can lead to changes at the holobiont, community, or even ecosystem level and vice versa, illustrating the necessity of considering multiple scales when evaluating functioning in nested ecosystems.

Some of these relationships include endosymbionts within bacteriocyte cells, and cyanobacteria or microalgae found below the pinacoderm cell layer where they are able to receive the highest amount of light, used for phototrophy. They can host over 50 different microbial phyla and candidate phyla, including Alphaprotoebacteria,

Actinomycetota,

Chloroflexota,

Nitrospirota, "

Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

", the taxa Gamma-, the candidate phylum

Poribacteria, and

Thaumarchaea.

Systematics

Taxonomy

Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

, who classified most kinds of sessile animals as belonging to the order

Zoophyta in the class

Vermes, mistakenly identified the genus ''

Spongia'' as plants in the order

Algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

.

For a long time thereafter, sponges were assigned to subkingdom

Parazoa ("beside the animals") separated from the

Eumetazoa which formed the rest of the

kingdom Animalia

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

.

The phylum Porifera is further divided into

classes mainly according to the composition of their

skeletons:

*

Hexactinellida (glass sponges) have silicate spicules, the largest of which have six rays and may be individual or fused.

The main components of their bodies are

syncytia in which large numbers of cell share a single external

membrane.

*

Calcarea have skeletons made of

calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

, a form of

calcium carbonate, which may form separate spicules or large masses. All the cells have a single nucleus and membrane.

* Most

Demospongiae have silicate spicules or

spongin fibers or both within their soft tissues. However, a few also have massive external skeletons made of

aragonite, another form of calcium carbonate.

All the cells have a single nucleus and membrane.

*

Archeocyatha are known only as fossils from the

Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

period.

In the 1970s, sponges with massive calcium carbonate skeletons were assigned to a separate class,

Sclerospongiae, otherwise known as "coralline sponges". However, in the 1980s, it was found that these were all members of either the Calcarea or the Demospongiae.

So far scientific publications have identified about 9,000 poriferan species,

of which about 400 are glass sponges, about 500 are calcareous species, and the rest are demosponges.

However, some types of habitat, such as vertical rock and cave walls and galleries in rock and coral boulders, have been investigated very little, even in shallow seas, and may harbor many more species.

Classes

Sponges were traditionally distributed in three classes: calcareous sponges (Calcarea), glass sponges (Hexactinellida) and demosponges (Demospongiae). However, studies have now shown that the

Homoscleromorpha, a group thought to belong to the

Demospongiae, has a

genetic relationship well separated from other sponge classes.

Therefore, they have recently been recognized as the fourth class of sponges.

Sponges are divided into

classes mainly according to the composition of their

skeletons:

These are arranged in evolutionary order as shown below in ascending order of their evolution from top to bottom:

:

Phylogeny

The phylogeny of sponges has been debated heavily since the advent of

phylogenetics

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

. Originally thought to be the most basal animal phylum, there is now considerable evidence that

Ctenophora may hold that title instead. Additionally, the

monophyly of the phylum is now under question. Several studies have concluded that

all other animals emerged from within the sponges, and usually recover that the

calcareous sponges and

Homoscleromorpha are closer to other animals than to

demosponge

Demosponges or common sponges are sponges of the class Demospongiae (from + ), the most diverse group in the phylum Porifera which include greater than 90% of all extant sponges with nearly 8,800 species

A species () is often de ...

s.

The internal relationships of Porifera have proven to be less uncertain. A close relationship of Homoscleromorpha and Calcarea has been recovered in nearly all studies, whether or not they support sponge or eumetazoan monophyly.

The position of

glass sponges is also fairly certain, with a majority of studies recovering them as the sister of the demosponges.

Thus, the uncertainty at the base of the animal family tree is probably best represented by the below cladogram.

Evolutionary history

Fossil record

Although

molecular clocks and

biomarkers suggest sponges existed well before the

Cambrian explosion of life,

silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

spicules like those of demosponges are absent from the fossil record until the Cambrian. An unsubstantiated 2002 report exists of spicules in rocks dated around . Well-preserved

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

sponges from about in the

Ediacaran

The Ediacaran ( ) is a geological period of the Neoproterozoic geologic era, Era that spans 96 million years from the end of the Cryogenian Period at 635 Million years ago, Mya to the beginning of the Cambrian Period at 538.8 Mya. It is the last ...

period have been found in the

Doushantuo Formation. These fossils, which include: spicules;

pinacocytes;

porocytes;

archeocytes;

sclerocytes; and the internal cavity, have been classified as demosponges. The Ediacaran record of sponges also contains two other genera: the stem-hexactinellid ''

Helicolocellus'' from the

Dengying Formation and the possible stem-archaeocyathan ''

Arimasia'' from the

Nama Group.

These genera are both from the "Nama assemblage" of Ediacaran biota, although whether this is due to a genuine lack beforehand or preservational bias is uncertain. Fossils of

glass sponges have been found from around in rocks in Australia, China, and Mongolia.

Early Cambrian sponges from Mexico belonging to the genus ''Kiwetinokia'' show evidence of fusion of several smaller spicules to form a single large spicule.

Calcium carbonate spicules of

calcareous sponges have been found in Early Cambrian rocks from about in Australia. Other probable demosponges have been found in the Early

Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

Chengjiang fauna, from .

Fossils found in the Canadian Northwest Territories dating to may be sponges; if this finding is confirmed, it suggests the first animals appeared before the Neoproterozoic oxygenation event.

Freshwater sponges appear to be much younger, as the earliest known fossils date from the Mid-

Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

period about .

Although about 90% of modern sponges are

demosponges, fossilized remains of this type are less common than those of other types because their skeletons are composed of relatively soft spongin that does not fossilize well.

The earliest sponge symbionts are known from the

early Silurian.

A chemical tracer is

24-isopropyl cholestane, which is a stable derivative of 24-isopropyl

cholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

, which is said to be produced by

demosponge

Demosponges or common sponges are sponges of the class Demospongiae (from + ), the most diverse group in the phylum Porifera which include greater than 90% of all extant sponges with nearly 8,800 species

A species () is often de ...

s but not by

eumetazoans ("true animals", i.e.

cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

ns and

bilateria

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left� ...

ns). Since

choanoflagellates are thought to be animals' closest single-celled relatives, a team of scientists examined the

biochemistry

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, a ...

and

gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s of one

choanoflagellate species. They concluded that this species could not produce 24-isopropyl cholesterol but that investigation of a wider range of choanoflagellates would be necessary in order to prove that the fossil 24-isopropyl cholestane could only have been produced by demosponges.

Although a previous publication reported traces of the chemical 24-isopropyl cholestane in ancient rocks dating to , recent research using a much more accurately dated rock series has revealed that these biomarkers only appear before the end of the

Marinoan glaciation approximately , and that "Biomarker analysis has yet to reveal any convincing evidence for ancient sponges pre-dating the first globally extensive Neoproterozoic glacial episode (the Sturtian, ~ in Oman)". While it has been argued that this 'sponge biomarker' could have originated from marine algae, recent research suggests that the algae's ability to produce this biomarker evolved only in the

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

; as such, the biomarker remains strongly supportive of the presence of demosponges in the Cryogenian.

s, which some classify as a type of coralline sponge, are very common fossils in rocks from the Early

Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

about , but apparently died out by the end of the Cambrian .

It has been suggested that they were produced by: sponges;

cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

ns;

algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

;

foraminiferans; a completely separate

phylum of animals, Archaeocyatha; or even a completely separate

kingdom of life, labeled Archaeata or Inferibionta. Since the 1990s, archaeocyathids have been regarded as a distinctive group of sponges.

It is difficult to fit

chancelloriids into classifications of sponges or more complex animals. An analysis in 1996 concluded that they were closely related to sponges on the grounds that the detailed structure of chancellorid sclerites ("armor plates") is similar to that of fibers of spongin, a

collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

, in modern keratose (horny)

demosponge

Demosponges or common sponges are sponges of the class Demospongiae (from + ), the most diverse group in the phylum Porifera which include greater than 90% of all extant sponges with nearly 8,800 species

A species () is often de ...

s such as ''

Darwinella''. However, another analysis in 2002 concluded that chancelloriids are not sponges and may be intermediate between sponges and more complex animals, among other reasons because their skins were thicker and more tightly connected than those of sponges.

[ free text at ] In 2008, a detailed analysis of chancelloriids' sclerites concluded that they were very similar to those of

halkieriids, mobile

bilaterian

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left–r ...

animals that looked like

slug

Slug, or land slug, is a common name for any apparently shell-less Terrestrial mollusc, terrestrial gastropod mollusc. The word ''slug'' is also often used as part of the common name of any gastropod mollusc that has no shell, a very reduced ...

s in

chain mail

Mail (sometimes spelled maille and, since the 18th century, colloquially referred to as chain mail, chainmail or chain-mail) is a type of armour consisting of small metal rings linked together in a pattern to form a mesh. It was in common milita ...

and whose fossils are found in rocks from the very Early Cambrian to the Mid Cambrian. If this is correct, it would create a dilemma, as it is extremely unlikely that totally unrelated organisms could have developed such similar sclerites independently, but the huge difference in the structures of their bodies makes it hard to see how they could be closely related.

Relationships to other animal groups

In the 1990s, sponges were widely regarded as a

monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

group, all of them having descended from a

common ancestor that was itself a sponge, and as the "sister-group" to all other

metazoans (multi-celled animals), which themselves form a monophyletic group. On the other hand, some 1990s analyses also revived the idea that animals' nearest evolutionary relatives are

choanoflagellates, single-celled organisms very similar to sponges'

choanocytes – which would imply that most Metazoa evolved from very sponge-like ancestors and therefore that sponges may not be monophyletic, as the same sponge-like ancestors may have given rise both to modern sponges and to non-sponge members of Metazoa.

Analyses since 2001 have concluded that

Eumetazoa (more complex than sponges) are more closely related to particular groups of sponges than to other sponge groups. Such conclusions imply that sponges are not monophyletic, because the

last common ancestor of all sponges would also be a direct ancestor of the Eumetazoa, which are not sponges. A study in 2001 based on comparisons of

ribosome DNA concluded that the most fundamental division within sponges was between

glass sponges and the rest, and that Eumetazoa are more closely related to

calcareous sponges (those with calcium carbonate spicules) than to other types of sponge.

In 2007, one analysis based on comparisons of

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

and another based mainly on comparison of spicules concluded that demosponges and glass sponges are more closely related to each other than either is to the calcareous sponges, which in turn are more closely related to Eumetazoa.

Other anatomical and biochemical evidence links the Eumetazoa with

Homoscleromorpha, a sub-group of demosponges. A comparison in 2007 of

nuclear DNA, excluding glass sponges and

comb jellies, concluded that:

*

Homoscleromorpha are most closely related to Eumetazoa;

* calcareous sponges are the next closest;

* the other demosponges are evolutionary "aunts" of these groups; and

* the

chancelloriids, bag-like animals whose fossils are found in

Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

rocks, may be sponges.

The

sperm

Sperm (: sperm or sperms) is the male reproductive Cell (biology), cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm ...

of Homoscleromorpha share features with the sperm of Eumetazoa, that sperm of other sponges lack. In both Homoscleromorpha and Eumetazoa layers of cells are bound together by attachment to a carpet-like basal membrane composed mainly of "typ IV"

collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

, a form of collagen not found in other sponges – although the

spongin fibers that reinforce the mesohyl of all demosponges is similar to "type IV" collagen.

The analyses described above concluded that sponges are closest to the ancestors of all Metazoa, of all multi-celled animals including both sponges and more complex groups. However, another comparison in 2008 of 150 genes in each of 21 genera, ranging from fungi to humans but including only two species of sponge, suggested that

comb jellies (

ctenophora) are the most basal lineage of the Metazoa included in the sample.

If this is correct, either modern comb jellies developed their complex structures independently of other Metazoa, or sponges' ancestors were more complex and all known sponges are drastically simplified forms. The study recommended further analyses using a wider range of sponges and other simple Metazoa such as

Placozoa

Placozoa ( ; ) is a phylum of free-living (non-parasitic) marine invertebrates. They are blob-like animals composed of aggregations of cells. Moving in water by ciliary motion, eating food by Phagocytosis, engulfment, reproducing by Fission (biol ...

.

However, reanalysis of the data showed that the computer algorithms used for analysis were misled by the presence of specific ctenophore genes that were markedly different from those of other species, leaving sponges as either the sister group to all other animals, or an ancestral paraphyletic grade. 'Family trees' constructed using a combination of all available data – morphological, developmental and molecular – concluded that the sponges are in fact a monophyletic group, and with the

cnidarians form the sister group to the bilaterians.

A very large and internally consistent alignment of 1,719 proteins at the metazoan scale, published in 2017, showed that (i) sponges – represented by Homoscleromorpha, Calcarea, Hexactinellida, and Demospongiae – are monophyletic, (ii) sponges are sister-group to all other multicellular animals, (iii) ctenophores emerge as the second-earliest branching animal lineage, and (iv)

placozoans emerge as the third animal lineage, followed by

cnidarians sister-group to bilaterians.

In March 2021, scientists from Dublin found additional evidence that sponges are the sister group to all other animals, while in May 2023, Schultz et al. found patterns of irreversible change in genome synteny that provide strong evidence that

ctenophores are the sister group to all other animals instead.

Notable spongiologists

*

Céline Allewaert

*

Patricia Bergquist

*

James Scott Bowerbank

*

Maurice Burton

*

Henry John Carter

*

Max Walker de Laubenfels

*

Arthur Dendy

*

Édouard Placide Duchassaing de Fontbressin

*

Randolph Kirkpatrick

*

Robert J. Lendlmayer von Lendenfeld

*

Edward Alfred Minchin

*

Giovanni Domenico Nardo

*

Eduard Oscar Schmidt

*

Émile Topsent

Use

By dolphins

A report in 1997 described use of sponges

as a tool by

bottlenose dolphins in

Shark Bay in Western Australia. A dolphin will attach a marine sponge to its

rostrum, which is presumably then used to protect it when searching for food in the sandy

sea bottom.

The behavior, known as ''sponging'', has only been observed in this bay and is almost exclusively shown by females. A study in 2005 concluded that mothers teach the behavior to their daughters and that all the sponge users are closely related, suggesting that it is a fairly recent innovation.

By humans

Skeleton

The

calcium carbonate or

silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

spicules of most sponge

genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

make them too rough for most uses, but two genera, ''

Hippospongia'' and ''

Spongia'', have soft, entirely fibrous skeletons.

Early Europeans used soft sponges for many purposes, including padding for helmets, portable drinking utensils and municipal water filters. Until the invention of synthetic sponges, they were used as cleaning tools, applicators for paints and

ceramic glazes and discreet

contraceptives. However, by the mid-20th century, overfishing brought both the animals and the industry close to

extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

.

Many objects with sponge-like textures are now made of substances not derived from poriferans. Synthetic sponges include personal and household

cleaning tools,

breast implants, and

contraceptive sponges.

Typical materials used are

cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

foam,

polyurethane

Polyurethane (; often abbreviated PUR and PU) is a class of polymers composed of organic chemistry, organic units joined by carbamate (urethane) links. In contrast to other common polymers such as polyethylene and polystyrene, polyurethane term ...

foam, and less frequently,

silicone

In Organosilicon chemistry, organosilicon and polymer chemistry, a silicone or polysiloxane is a polymer composed of repeating units of siloxane (, where R = Organyl group, organic group). They are typically colorless oils or elastomer, rubber ...

foam.

The

luffa "sponge", also spelled ''loofah'', which is commonly sold for use in the kitchen or the shower, is not derived from an animal but mainly from the fibrous "skeleton" of the

sponge gourd (''Luffa aegyptiaca'',

Cucurbitaceae).

File:2008.09-331-196ap Sponge gourd,pd Spice Bazaar@Istanbul,TR mon29sep2008-1315h.jpg, Sponges made of sponge gourd for sale alongside sponges of animal origin, Spice Bazaar, Istanbul

File:SpongesTarponSprings.jpg, Natural sponges in Tarpon Springs, Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

Medicinal compounds

Sponges have