Space Shuttle Challenger disaster on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

On January 28, 1986, the Space Shuttle ''Challenger'' broke apart 73 seconds into its flight, killing all seven crew members aboard. The spacecraft disintegrated above the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of

The

The

Evaluations of the proposed SRB design in the early 1970s and field joint testing showed that the wide tolerances between the mated parts allowed the O-rings to be

Evaluations of the proposed SRB design in the early 1970s and field joint testing showed that the wide tolerances between the mated parts allowed the O-rings to be

When the teleconference prepared to hold a recess to allow for private discussion amongst Morton Thiokol management, Allan J. McDonald, Morton Thiokol's Director of the Space Shuttle SRM Project who was sitting at the KSC end of the call, reminded his colleagues in Utah to examine the interaction between delays in the primary O-rings sealing relative to the ability of the secondary O-rings to provide redundant backup, believing this would add enough to the engineering analysis to get Mulloy to stop accusing the engineers of using inconclusive evidence to try and delay the launch. When the call resumed, Morton Thiokol leadership had changed their opinion and stated that the evidence presented on the failure of the O-rings was inconclusive and that there was a substantial margin in the event of a failure or erosion. They stated that their decision was to proceed with the launch. When McDonald told Mulloy that, as the onsite representative at KSC he would not sign off on the decision, Mulloy demanded that Morton Thiokol provide a signed recommendation to launch; Kilminster confirmed that he would sign it and

When the teleconference prepared to hold a recess to allow for private discussion amongst Morton Thiokol management, Allan J. McDonald, Morton Thiokol's Director of the Space Shuttle SRM Project who was sitting at the KSC end of the call, reminded his colleagues in Utah to examine the interaction between delays in the primary O-rings sealing relative to the ability of the secondary O-rings to provide redundant backup, believing this would add enough to the engineering analysis to get Mulloy to stop accusing the engineers of using inconclusive evidence to try and delay the launch. When the call resumed, Morton Thiokol leadership had changed their opinion and stated that the evidence presented on the failure of the O-rings was inconclusive and that there was a substantial margin in the event of a failure or erosion. They stated that their decision was to proceed with the launch. When McDonald told Mulloy that, as the onsite representative at KSC he would not sign off on the decision, Mulloy demanded that Morton Thiokol provide a signed recommendation to launch; Kilminster confirmed that he would sign it and

At T+0, ''Challenger'' launched from the

At T+0, ''Challenger'' launched from the

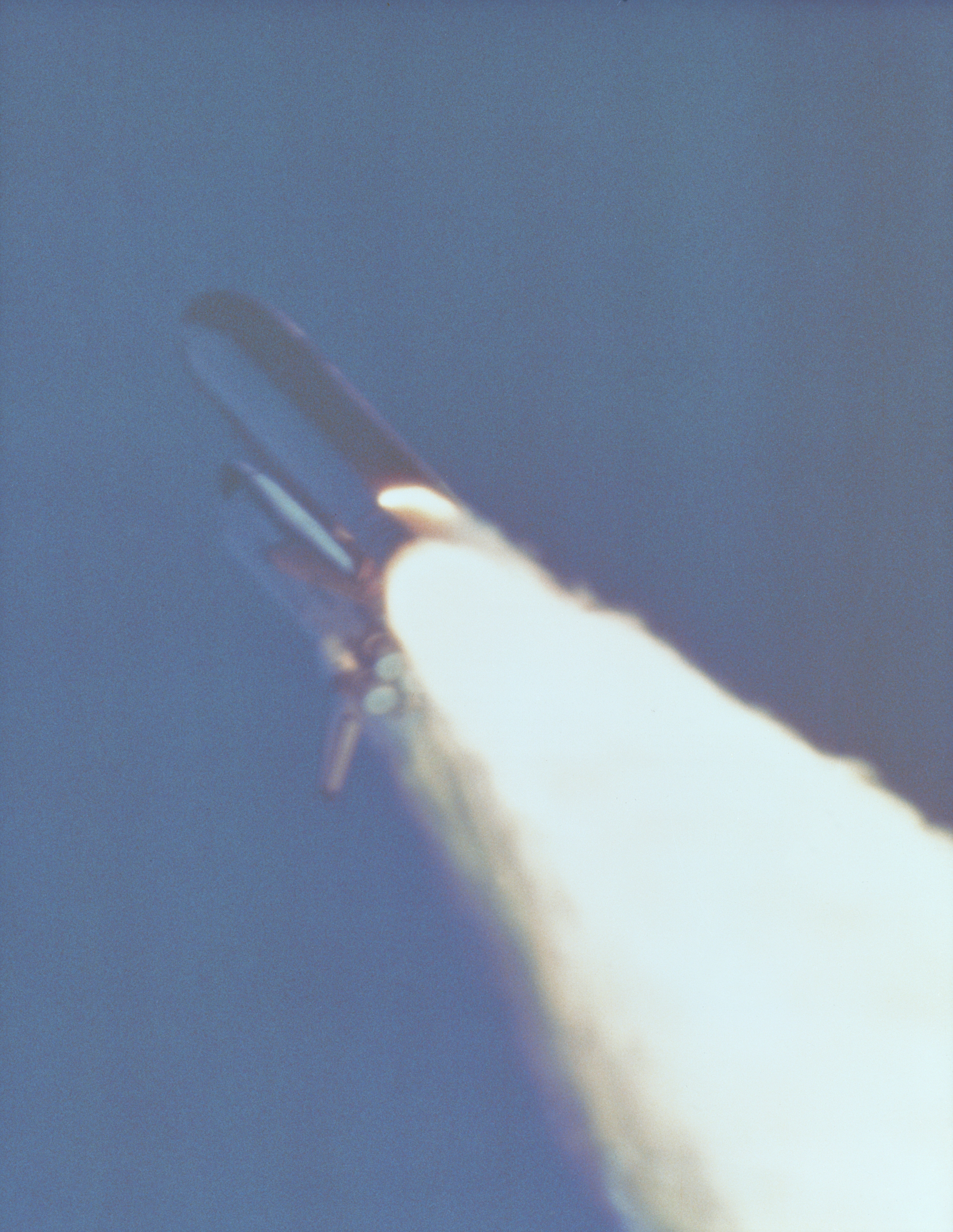

At , a tracking film camera captured the beginnings of a plume near the aft attach strut on the right SRB, right before the vehicle passed through max q at . The high aerodynamic forces and wind shear likely broke the unintentional aluminum oxide seal that had replaced eroded O-rings, allowing the flame to burn through the joint. Within one second from when it was first recorded, the plume became well-defined, and the enlarging hole caused a drop in internal pressure in the right SRB. A leak had begun in the

At , a tracking film camera captured the beginnings of a plume near the aft attach strut on the right SRB, right before the vehicle passed through max q at . The high aerodynamic forces and wind shear likely broke the unintentional aluminum oxide seal that had replaced eroded O-rings, allowing the flame to burn through the joint. Within one second from when it was first recorded, the plume became well-defined, and the enlarging hole caused a drop in internal pressure in the right SRB. A leak had begun in the

At , the right SRB pulled away from the aft strut that attached it to the ET, causing lateral acceleration that was felt by the crew. At the same time, pressure in the LH2 tank began dropping. Pilot Mike Smith said "Uh-oh," which was the last crew comment recorded. At , white vapor was seen flowing away from the ET, after which the aft dome of the LH2 tank fell off. The resulting release and ignition of all liquid hydrogen in the tank pushed the LH2 tank forward into the

At , the right SRB pulled away from the aft strut that attached it to the ET, causing lateral acceleration that was felt by the crew. At the same time, pressure in the LH2 tank began dropping. Pilot Mike Smith said "Uh-oh," which was the last crew comment recorded. At , white vapor was seen flowing away from the ET, after which the aft dome of the LH2 tank fell off. The resulting release and ignition of all liquid hydrogen in the tank pushed the LH2 tank forward into the

At , there was a burst of static on the air-to-ground loop as the vehicle broke up, which was later attributed to ground-based radios searching for a signal from the destroyed spacecraft. NASA Public Affairs Officer Steve Nesbitt was initially unaware of the explosion and continued to read out flight information. At , after video of the explosion was seen in Mission Control, the Ground Control Officer reported "negative contact (and) loss of

At , there was a burst of static on the air-to-ground loop as the vehicle broke up, which was later attributed to ground-based radios searching for a signal from the destroyed spacecraft. NASA Public Affairs Officer Steve Nesbitt was initially unaware of the explosion and continued to read out flight information. At , after video of the explosion was seen in Mission Control, the Ground Control Officer reported "negative contact (and) loss of

The crew cabin, which was made of reinforced aluminum, separated in one piece from the rest of the orbiter. It then traveled in a ballistic arc, reaching the

The crew cabin, which was made of reinforced aluminum, separated in one piece from the rest of the orbiter. It then traveled in a ballistic arc, reaching the

The commission determined that the cause of the accident was hot gas blowing past the O-rings in the field joint on the right SRB, and found no other potential causes for the disaster. It attributed the accident to a faulty design of the field joint that was unacceptably sensitive to changes in temperature, dynamic loading, and the character of its materials. The report was critical of NASA and Morton Thiokol, and emphasized that both organizations had overlooked evidence that indicated the potential danger with the SRB field joints. It noted that NASA accepted the risk of O-ring erosion without evaluating how it could potentially affect the safety of a mission. The commission concluded that the safety culture and management structure at NASA were insufficient to properly report, analyze, and prevent flight issues. It stated that the pressure to increase the rate of flights negatively affected the amount of training, quality control, and repair work that was available for each mission.

The commission published a series of recommendations to improve the safety of the Space Shuttle program. It proposed a redesign of the joints in the SRB that would prevent gas from blowing past the O-rings. It also recommended that the program's management be restructured to keep project managers from being pressured to adhere to unsafe organizational deadlines, and should include astronauts to address crew safety concerns better. It proposed that an office for safety be established reporting directly to the NASA administrator to oversee all safety, reliability, and quality assurance functions in NASA programs. Additionally, the commission addressed issues with overall safety and maintenance for the orbiter, and it recommended the addition of the means for the crew to escape during controlled gliding flight.

During a televised hearing on February11, Feynman demonstrated the loss of rubber's elasticity in cold temperatures using a glass of cold water and a piece of rubber, for which he received media attention. Feynman, a

The commission determined that the cause of the accident was hot gas blowing past the O-rings in the field joint on the right SRB, and found no other potential causes for the disaster. It attributed the accident to a faulty design of the field joint that was unacceptably sensitive to changes in temperature, dynamic loading, and the character of its materials. The report was critical of NASA and Morton Thiokol, and emphasized that both organizations had overlooked evidence that indicated the potential danger with the SRB field joints. It noted that NASA accepted the risk of O-ring erosion without evaluating how it could potentially affect the safety of a mission. The commission concluded that the safety culture and management structure at NASA were insufficient to properly report, analyze, and prevent flight issues. It stated that the pressure to increase the rate of flights negatively affected the amount of training, quality control, and repair work that was available for each mission.

The commission published a series of recommendations to improve the safety of the Space Shuttle program. It proposed a redesign of the joints in the SRB that would prevent gas from blowing past the O-rings. It also recommended that the program's management be restructured to keep project managers from being pressured to adhere to unsafe organizational deadlines, and should include astronauts to address crew safety concerns better. It proposed that an office for safety be established reporting directly to the NASA administrator to oversee all safety, reliability, and quality assurance functions in NASA programs. Additionally, the commission addressed issues with overall safety and maintenance for the orbiter, and it recommended the addition of the means for the crew to escape during controlled gliding flight.

During a televised hearing on February11, Feynman demonstrated the loss of rubber's elasticity in cold temperatures using a glass of cold water and a piece of rubber, for which he received media attention. Feynman, a

In 2004, President

In 2004, President  Several memorials have been established in honor of the ''Challenger'' disaster. The public Peers Park in

Several memorials have been established in honor of the ''Challenger'' disaster. The public Peers Park in

In the years immediately after the ''Challenger'' disaster, several books were published describing the factors and causes of the accident and the subsequent investigation and changes. In 1987, Malcolm McConnell, a journalist and a witness of the disaster, published ''Challenger–A Major Malfunction: A True Story of Politics, Greed, and the Wrong Stuff''. McConnell's book was criticized for arguing for a conspiracy involving NASA Administrator Fletcher awarding the contract to Morton Thiokol because it was from his home state of Utah. The book ''Prescription for Disaster: From the Glory of Apollo to the Betrayal of the Shuttle'' by Joseph Trento was also published in 1987, arguing that the Space Shuttle program had been a flawed and politicized program from its inception. In 1988, Feynman's memoir, ''"What Do You Care What Other People Think?": Further Adventures of a Curious Character'', was published. The latter half of the book discusses his involvement in the Rogers Commission and his relationship with Kutyna.

Books were published long after the disaster. In 1996, Diane Vaughan published ''The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA'', which argues that NASA's structure and mission, rather than just Space Shuttle program management, created a climate of risk acceptance that resulted in the disaster. Also in 1996, Claus Jensen published ''No Downlink: A Dramatic Narrative About the Challenger Accident and Our Time'' that primarily discusses the development of rocketry prior to the disaster, and was criticized for its reliance on secondary sources with little original research conducted for the book. In 2009, Allan McDonald published his memoir written with space historian James Hansen, ''Truth, Lies, and O-Rings: Inside the Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster'', which focuses on his personal involvement in the launch, disaster, investigation, and return to flight, and is critical of NASA and Morton Thiokol leadership for agreeing to launch ''Challenger'' despite engineers' warnings about the O-rings.Alt URL

In the years immediately after the ''Challenger'' disaster, several books were published describing the factors and causes of the accident and the subsequent investigation and changes. In 1987, Malcolm McConnell, a journalist and a witness of the disaster, published ''Challenger–A Major Malfunction: A True Story of Politics, Greed, and the Wrong Stuff''. McConnell's book was criticized for arguing for a conspiracy involving NASA Administrator Fletcher awarding the contract to Morton Thiokol because it was from his home state of Utah. The book ''Prescription for Disaster: From the Glory of Apollo to the Betrayal of the Shuttle'' by Joseph Trento was also published in 1987, arguing that the Space Shuttle program had been a flawed and politicized program from its inception. In 1988, Feynman's memoir, ''"What Do You Care What Other People Think?": Further Adventures of a Curious Character'', was published. The latter half of the book discusses his involvement in the Rogers Commission and his relationship with Kutyna.

Books were published long after the disaster. In 1996, Diane Vaughan published ''The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA'', which argues that NASA's structure and mission, rather than just Space Shuttle program management, created a climate of risk acceptance that resulted in the disaster. Also in 1996, Claus Jensen published ''No Downlink: A Dramatic Narrative About the Challenger Accident and Our Time'' that primarily discusses the development of rocketry prior to the disaster, and was criticized for its reliance on secondary sources with little original research conducted for the book. In 2009, Allan McDonald published his memoir written with space historian James Hansen, ''Truth, Lies, and O-Rings: Inside the Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster'', which focuses on his personal involvement in the launch, disaster, investigation, and return to flight, and is critical of NASA and Morton Thiokol leadership for agreeing to launch ''Challenger'' despite engineers' warnings about the O-rings.Alt URL

/ref>

Rogers Commission Report NASA webpage (crew tribute, five report volumes and appendices)

*

7 myths about the Challenger shuttle disaster: It didn't explode, the crew didn't die instantly and it wasn't inevitable

MSNBC.com

BBC World Service June 2017 documentary

* CBS Radio news bulletin of the ''Challenger'' disaster anchored by Christopher Glenn from January 28, 1986

Part 1Part 2Part 3

an

Part 4

{{Authority control 1986 disasters in the United States 1986 in Florida 1986 in spaceflight 1986 industrial disasters Accidental deaths in Florida Articles containing video clips Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States in 1986 Destroyed spacecraft Disasters in Florida Explosions in 1986 Gas explosions in the United States C Marine salvage operations History of Brevard County, Florida January 1986 in the United States Presidency of Ronald Reagan Space Shuttle program

Cape Canaveral

Cape Canaveral () is a cape (geography), cape in Brevard County, Florida, in the United States, near the center of the state's Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. Officially Cape Kennedy from 1963 to 1973, it lies east of Merritt Island, separated ...

, Florida, at 16:39:13UTC

Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) is the primary time standard globally used to regulate clocks and time. It establishes a reference for the current time, forming the basis for civil time and time zones. UTC facilitates international communica ...

(11:39:13a.m. EST, local time at the launch site). It was the first fatal accident involving an American spacecraft while in flight.

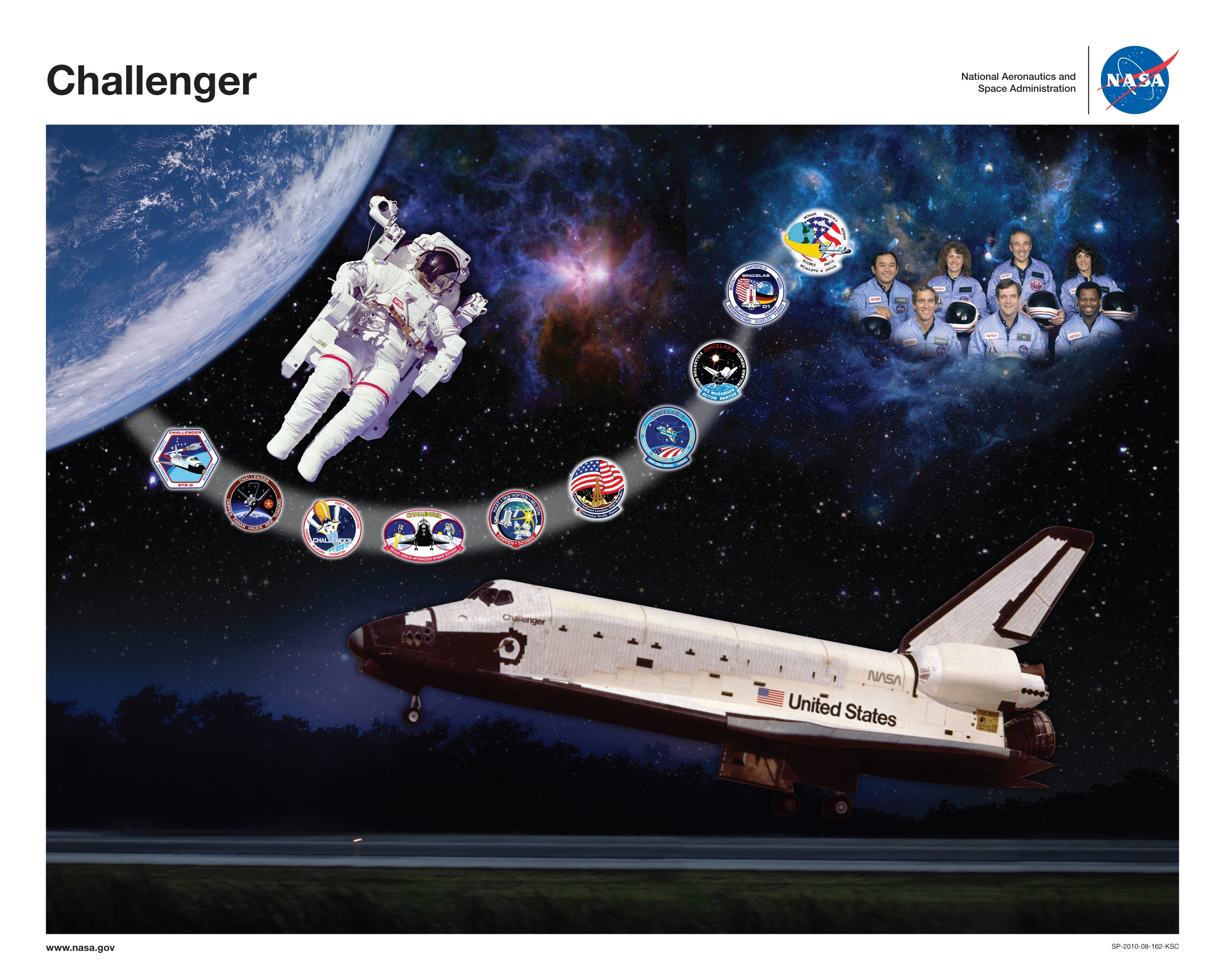

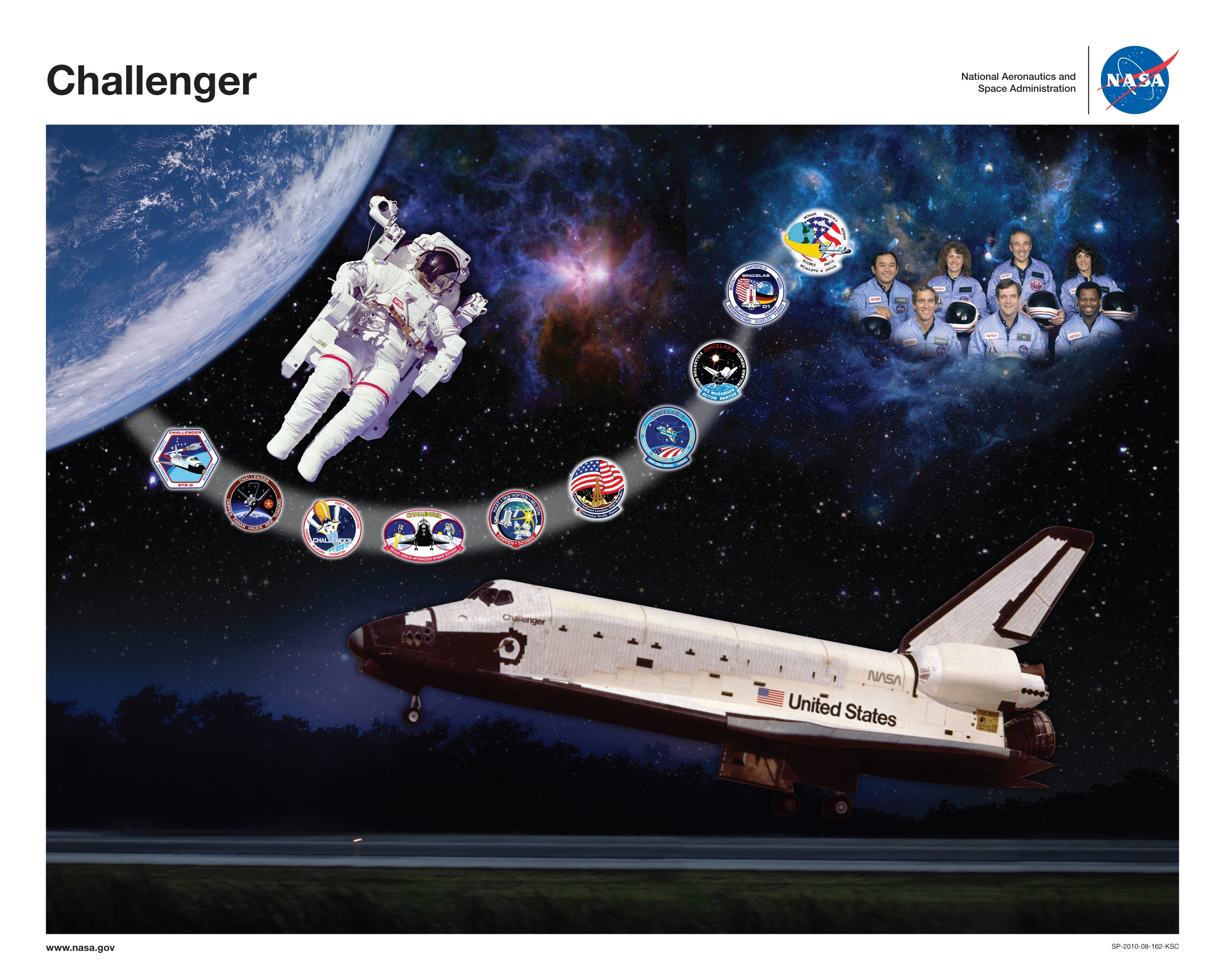

The mission, designated STS-51-L

STS-51-L was the disastrous 25th mission of NASA's Space Shuttle program and the final flight of Space Shuttle ''Challenger''.

It was planned as the first Teacher in Space Project flight in addition to observing Halley's Comet for six day ...

, was the 10th flight for the orbiter

A spacecraft is a vehicle that is designed to fly and operate in outer space. Spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, planetary exploration, ...

and the 25th flight of the Space Shuttle fleet. The crew was scheduled to deploy a commercial communications satellite and study Halley's Comet

Halley's Comet is the only known List of periodic comets, short-period comet that is consistently visible to the naked eye from Earth, appearing every 72–80 years, though with the majority of recorded apparitions (25 of 30) occurring after ...

while they were in orbit, in addition to taking schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe into space under the Teacher in Space Project. The latter task resulted in a higher-than-usual media interest in and coverage of the mission; the launch and subsequent disaster were seen live in many schools across the United States.

The cause of the disaster was the failure of the primary and secondary O-ring

An O-ring, also known as a packing or a toric joint, is a mechanical gasket in the shape of a torus; it is a loop of elastomer with a round cross section (geometry), cross-section, designed to be seated in a groove and compressed during assembl ...

seals in a joint in the right Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster

The Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) was the first solid-propellant rocket to be used for primary propulsion on a vehicle used for human spaceflight. A pair of them provided 85% of the Space Shuttle's thrust at liftoff and for the first ...

(SRB). The record-low temperatures on the morning of the launch had stiffened the rubber O-rings, reducing their ability to seal the joints. Shortly after liftoff, the seals were breached, and hot pressurized gas from within the SRB leaked through the joint and burned through the aft attachment strut connecting it to the external propellant tank (ET), then into the tank itself. The collapse of the ET's internal structures and the rotation of the SRB that followed propelled the shuttle stack, traveling at a speed of Mach

The Mach number (M or Ma), often only Mach, (; ) is a dimensionless quantity in fluid dynamics representing the ratio of flow velocity past a Boundary (thermodynamic), boundary to the local speed of sound.

It is named after the Austrian physi ...

1.92, into a direction that allowed aerodynamic force

In fluid mechanics, an aerodynamic force is a force exerted on a body by the air (or other gas) in which the body is immersed, and is due to the relative motion between the body and the gas.

Force

There are two causes of aerodynamic force:

* ...

s to tear the orbiter apart. Both SRBs detached from the now-destroyed ET and continued to fly uncontrollably until the range safety

In rocketry, range safety or flight safety is ensured by monitoring the flight paths of missiles and launch vehicles, and enforcing strict guidelines for rocket construction and ground-based operations. Various measures are implemented to protect ...

officer destroyed them.

The crew compartment, containing human remains, and many other fragments from the shuttle were recovered from the ocean floor after a three-month search and recovery operation. The exact timing of the deaths of the crew is unknown, but several crew members are thought to have survived the initial breakup of the spacecraft. The orbiter had no escape system, and the impact of the crew compartment at terminal velocity

Terminal velocity is the maximum speed attainable by an object as it falls through a fluid (air is the most common example). It is reached when the sum of the drag force (''Fd'') and the buoyancy is equal to the downward force of gravity (''FG ...

with the ocean surface was too violent to be survivable.

The disaster resulted in a 32-month hiatus in the Space Shuttle program

The Space Shuttle program was the fourth human spaceflight program carried out by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which accomplished routine transportation for Earth-to-orbit crew and cargo from 1981 to 2011. Its ...

. President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

created the Rogers Commission to investigate the accident. The commission criticized NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

's organizational culture and decision-making processes that had contributed to the accident. Test data since 1977 had demonstrated a potentially catastrophic flaw in the SRBs' O-rings, but neither NASA nor SRB manufacturer Morton Thiokol had addressed this known defect. NASA managers also disregarded engineers' warnings about the dangers of launching in low temperatures and did not report these technical concerns to their superiors.

As a result of this disaster, NASA established the Office of Safety, Reliability, and Quality Assurance, and arranged for deployment of commercial satellites from expendable launch vehicles rather than from a crewed orbiter. To replace ''Challenger'', the construction of a new Space Shuttle orbiter,, was approved in 1987, and the new orbiter first flew in 1992. Subsequent missions were launched with redesigned SRBs and their crews wore pressurized suits during ascent and reentry.

Background

Space Shuttle

The

The Space Shuttle

The Space Shuttle is a retired, partially reusable launch system, reusable low Earth orbital spacecraft system operated from 1981 to 2011 by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program. ...

was a partially reusable spacecraft operated by the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the United States's civil space program, aeronautics research and space research. Established in 1958, it su ...

(NASA). It flew for the first time in April 1981, and was used to conduct in-orbit research, and deploy commercial, military, and scientific payloads. At launch, it consisted of the orbiter

A spacecraft is a vehicle that is designed to fly and operate in outer space. Spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, planetary exploration, ...

, which contained the crew

A crew is a body or a group of people who work at a common activity, generally in a structured or hierarchy, hierarchical organization. A location in which a crew works is called a crewyard or a workyard. The word has nautical resonances: the ta ...

and payload, the external tank (ET), and the two solid rocket boosters (SRBs). The orbiter was a reusable, winged vehicle that launched vertically and landed as a glider. Five orbiters were built during the Space Shuttle program

The Space Shuttle program was the fourth human spaceflight program carried out by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which accomplished routine transportation for Earth-to-orbit crew and cargo from 1981 to 2011. Its ...

. ''Challenger'' (OV-099) was the second orbiter constructed after its conversion from a structural test article. The orbiter contained the crew compartment, where the crew predominantly lived and worked throughout a mission. Three Space Shuttle main engines

The RS-25, also known as the Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME), is a liquid-fuel cryogenic rocket engine that was used on NASA's Space Shuttle and is used on the Space Launch System.

Designed and manufactured in the United States by Rocketd ...

(SSMEs) were mounted at the aft end of the orbiter and provided thrust during launch. Once in space, the crew maneuvered using the two smaller, aft-mounted Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines.

When it launched, the orbiter was connected to the ET, which held the fuel for the SSMEs. The ET consisted of a larger tank for liquid hydrogen (LH2) and a smaller tank for liquid oxygen (LOX), both of which were required for the SSMEs to operate. After its fuel had been expended, the ET separated from the orbiter and reentered the atmosphere, where it would break apart during reentry and its pieces would land in the Indian or Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

.

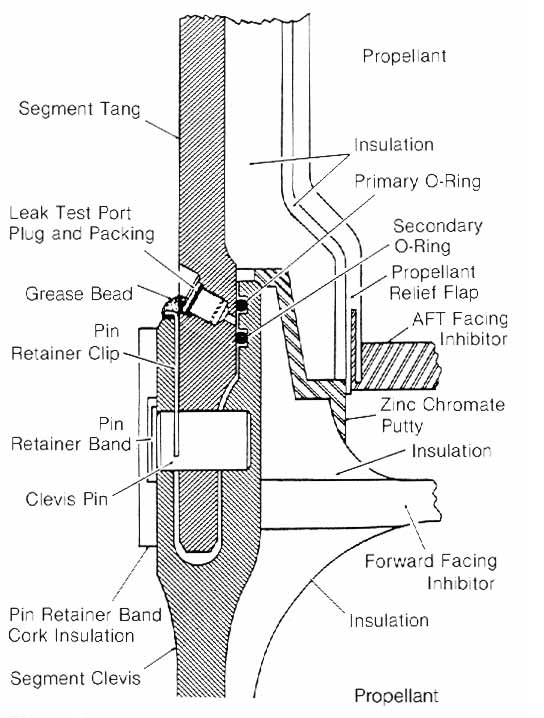

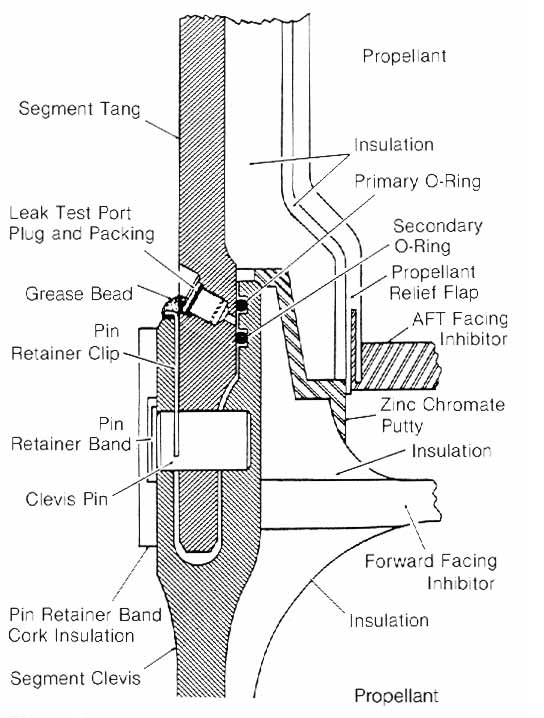

Two solid rocket boosters (SRBs), built by Morton Thiokol at the time of the disaster, provided the majority of thrust at liftoff. They were connected to the external tank, and burned for the first two minutes of flight. The SRBs separated from the orbiter once they had expended their fuel and fell into the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

under a parachute. NASA retrieval teams recovered the SRBs and returned them to the Kennedy Space Center

The John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC, originally known as the NASA Launch Operations Center), located on Merritt Island, Florida, is one of the NASA, National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) ten NASA facilities#List of field c ...

(KSC), where they were disassembled and their components were reused on future flights. Each SRB was constructed in four main sections at the factory in Utah and transported to KSC, then assembled in the Vehicle Assembly Building

The Vehicle Assembly Building (originally the Vertical Assembly Building), or VAB, is a large building at NASA's Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, designed to assemble large pre-manufactured space vehicle components, such as the massive Satu ...

at KSC with three tang-and-clevis field joints, each joint consisting of a tang from the upper segment fitting into the clevis of the lower segment. Each field joint was sealed with two ~20 foot (6 meter) diameter Viton-rubber O-rings around the circumference of the SRB and had a cross-section diameter of . The O-rings were required to contain the hot, high-pressure gases produced by the burning solid propellant and allowed for the SRBs to be rated for crewed missions. The two O-rings were configured to create a double bore seal, and the gap between segments was filled with putty. When the motor was running, this configuration was designed to compress air in the gap against the upper O-ring, pressing it against the sealing surfaces of its seat. On the SRB Critical Items List, the O-rings were listed as Criticality 1R, which indicated that an O-ring failure could result in the destruction of the vehicle and loss of life, but it was considered a redundant system due to the secondary O-ring.

O-ring concerns

Evaluations of the proposed SRB design in the early 1970s and field joint testing showed that the wide tolerances between the mated parts allowed the O-rings to be

Evaluations of the proposed SRB design in the early 1970s and field joint testing showed that the wide tolerances between the mated parts allowed the O-rings to be extruded

Extrusion is a process used to create objects of a fixed cross-sectional profile by pushing material through a die of the desired cross-section. Its two main advantages over other manufacturing processes are its ability to create very complex ...

from their seats rather than compressed. This extrusion was judged to be acceptable by NASA and Morton Thiokol despite concerns of NASA's engineers. A 1977 test showed that up to of joint rotation occurred during the simulated internal pressure of a launch. Joint rotation, which occurred when the tang and clevis bent away from each other, reduced the pressure on the O-rings, which weakened their seals and made it possible for combustion gases to erode the O-rings. NASA engineers suggested that the field joints should be redesigned to include shims around the O-rings, but they received no response. In 1980, the NASA Verification/Certification Committee requested further tests on joint integrity to include testing in the temperature range of and with only a single O-ring installed. The NASA program managers decided that their current level of testing was sufficient and further testing was not required. In December1982, the Critical Items List was updated to indicate that the secondary O-ring could not provide a backup to the primary O-ring, as it would not necessarily form a seal in the event of joint rotation. The O-rings were redesignated as Criticality1, removing the "R" to indicate it was no longer considered a redundant system.

The first occurrence of in-flight O-ring erosion occurred on the right SRB on in November1981. In August1984, a post-flight inspection of the left SRB on revealed that soot had blown past the primary O-ring and was found in between the O-rings. Although there was no damage to the secondary O-ring, this indicated that the primary O-ring was not creating a reliable seal and was allowing hot gas to pass. The amount of O-ring erosion was insufficient to prevent the O-ring from sealing, and investigators concluded that the soot between the O-rings resulted from non-uniform pressure at the time of ignition. The January1985 launch of was the coldest Space Shuttle launch to date. The air temperature was at the time of launch, and the calculated O-ring temperature was . Post-flight analysis revealed erosion in primary O-rings in both SRBs. Morton Thiokol engineers determined that the cold temperatures caused a loss of flexibility in the O-rings that decreased their ability to seal the field joints, which allowed hot gas and soot to flow past the primary O-ring. O-ring erosion occurred on all but one () of the Space Shuttle flights in 1985, and erosion of both the primary and secondary O-rings occurred on .

To correct the issues with O-ring erosion, engineers at Morton Thiokol, led by Allan McDonald and Roger Boisjoly, proposed a redesigned field joint that introduced a metal lip to limit movement in the joint. They also recommended adding a spacer to provide additional thermal protection and using an O-ring with a larger cross section. In July1985, Morton Thiokol ordered redesigned SRB casings, with the intention of using already-manufactured casings for the upcoming launches until the redesigned cases were available the following year.

Mission

The Space Shuttle mission, named , was the twenty-fifth Space Shuttle flight and the tenth flight of. The crew was announced on January27,1985, and was commanded by Dick Scobee. Michael Smith was assigned as the pilot, and themission specialist

Mission specialist (MS) is a term for a specific position held by astronauts who are tasked with conducting a range of scientific, medical, or engineering experiments during a spaceflight mission. These specialists were usually assigned to a s ...

s were Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, and Ronald McNair. The two payload specialist

A payload specialist (PS) was an individual selected and trained by commercial or research organizations for flights of a specific payload on a NASA Space Shuttle mission. People assigned as payload specialists included individuals selected by t ...

s were Gregory Jarvis, who was assigned to conduct research for the Hughes Aircraft Company

The Hughes Aircraft Company was a major American aerospace and defense contractor founded on February 14, 1934 by Howard Hughes in Glendale, California, as a division of the Hughes Tool Company. The company produced the Hughes H-4 Hercules air ...

, and Christa McAuliffe, who flew as part of the Teacher in Space Project.

The primary mission of the ''Challenger'' crew was to use an Inertial Upper Stage

The Inertial Upper Stage (IUS), originally designated the Interim Upper Stage, was a Multistage rocket, two-stage, Solid-propellant rocket, solid-fueled space launch system developed by Boeing for the United States Air Force beginning in 1976 for ...

(IUS) to deploy a Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS), named TDRS-B

TDRS-B was an American communications satellite, of first generation, which was to have formed part of the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System. It was destroyed in 1986 when the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, disintegrated 73 seconds a ...

, that would have been part of a constellation to enable constant communication with orbiting spacecraft. The crew also planned to study Halley's Comet

Halley's Comet is the only known List of periodic comets, short-period comet that is consistently visible to the naked eye from Earth, appearing every 72–80 years, though with the majority of recorded apparitions (25 of 30) occurring after ...

as it passed near the Sun, and deploy and retrieve a SPARTAN satellite.

The mission was originally scheduled for July1985, but was delayed to November and then to January1986. The mission was scheduled to launch on January22, but was delayed until January 28.

Decision to launch

The air temperature on January 28 was predicted to be a record low for a Space Shuttle launch. The air temperature was forecast to drop to overnight before rising to at 6:00a.m. and at the scheduled launch time of 9:38a.m. Based upon O-ring erosion that had occurred in warmer launches, Morton Thiokol engineers were concerned over the effect the record-cold temperatures would have on the seal provided by the SRB O-rings for the launch. Cecil Houston, the manager of the KSC office of theMarshall Space Flight Center

Marshall Space Flight Center (officially the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center; MSFC), located in Redstone Arsenal, Alabama (Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville postal address), is the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government's ...

in Alabama, set up a three-way conference call with Morton Thiokol in Utah and the KSC in Florida on the evening of January 27 to discuss the safety of the launch. Morton Thiokol engineers expressed their concerns about the effect of low temperatures on the resilience of the rubber O-rings. As the colder temperatures lowered the elasticity of the rubber O-rings, the engineers feared that the O-rings would not be extruded to form a seal at the time of launch. The engineers argued that they did not have enough data to determine whether the O-rings would seal at temperatures colder than , the coldest launch of the Space Shuttle to date. During this discussion, Lawrence Mulloy, the NASA SRB project manager, said that he did not accept the analysis behind this decision, and demanded to know if Morton Thiokol expected him to wait until April for warmer temperatures. Morton Thiokol employees Robert Lund, the Vice President of Engineering, and Joe Kilminster, the Vice President of the Space Booster Programs, recommended against launching until the temperature was above .

When the teleconference prepared to hold a recess to allow for private discussion amongst Morton Thiokol management, Allan J. McDonald, Morton Thiokol's Director of the Space Shuttle SRM Project who was sitting at the KSC end of the call, reminded his colleagues in Utah to examine the interaction between delays in the primary O-rings sealing relative to the ability of the secondary O-rings to provide redundant backup, believing this would add enough to the engineering analysis to get Mulloy to stop accusing the engineers of using inconclusive evidence to try and delay the launch. When the call resumed, Morton Thiokol leadership had changed their opinion and stated that the evidence presented on the failure of the O-rings was inconclusive and that there was a substantial margin in the event of a failure or erosion. They stated that their decision was to proceed with the launch. When McDonald told Mulloy that, as the onsite representative at KSC he would not sign off on the decision, Mulloy demanded that Morton Thiokol provide a signed recommendation to launch; Kilminster confirmed that he would sign it and

When the teleconference prepared to hold a recess to allow for private discussion amongst Morton Thiokol management, Allan J. McDonald, Morton Thiokol's Director of the Space Shuttle SRM Project who was sitting at the KSC end of the call, reminded his colleagues in Utah to examine the interaction between delays in the primary O-rings sealing relative to the ability of the secondary O-rings to provide redundant backup, believing this would add enough to the engineering analysis to get Mulloy to stop accusing the engineers of using inconclusive evidence to try and delay the launch. When the call resumed, Morton Thiokol leadership had changed their opinion and stated that the evidence presented on the failure of the O-rings was inconclusive and that there was a substantial margin in the event of a failure or erosion. They stated that their decision was to proceed with the launch. When McDonald told Mulloy that, as the onsite representative at KSC he would not sign off on the decision, Mulloy demanded that Morton Thiokol provide a signed recommendation to launch; Kilminster confirmed that he would sign it and fax

Fax (short for facsimile), sometimes called telecopying or telefax (short for telefacsimile), is the telephonic transmission of scanned printed material (both text and images), normally to a telephone number connected to a printer or other out ...

it from Utah immediately, and the teleconference ended. Mulloy called Arnold Aldrich, the NASA Mission Management Team Leader, to discuss the launch decision and weather concerns, but did not mention the O-ring discussion; the two agreed to proceed with the launch.

An overnight measurement taken by the KSC Ice Team recorded the left SRB was and the right SRB was . These measurements were recorded for engineering data and not reported, because the temperature of the SRBs was not part of the Launch Commit Criteria. In addition to its effect on the O-rings, the cold temperatures caused ice to form on the fixed service structure. To keep pipes from freezing, water was slowly run from the system; it could not be entirely drained because of the upcoming launch. As a result, ice formed from down in the freezing temperatures. Engineers at Rockwell International

Rockwell International was a major American manufacturing conglomerate (company), conglomerate. It was involved in aircraft, the space industry, defense and commercial electronics, components in the automotive industry, printing presses, avioni ...

, which manufactured the orbiter, were concerned that ice would be violently thrown during launch and could potentially damage the orbiter's thermal protection system or be aspirated into one of the engines. Rocco Petrone

Rocco Anthony Petrone (March 31, 1926 – August 24, 2006) was an American mechanical engineer, U.S. Army officer and NASA official. He served as director of launch operations at NASA's John F. Kennedy Space Center, Kennedy Space Center (KSC) ...

, the head of Rockwell's space transportation division, and his team determined that the potential damage from ice made the mission unsafe to fly. Arnold Aldrich consulted with engineers at KSC and the Johnson Space Center

The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) is NASA's center for human spaceflight in Houston, Texas (originally named the Manned Spacecraft Center), where human spaceflight training, research, and flight controller, flight control are conducted. ...

(JSC) who advised him that ice did not threaten the safety of the orbiter, and he decided to proceed with the launch. The launch was delayed for an additional hour to allow more ice to melt. The ice team performed an inspection at T–20 minutes which indicated that the ice was melting, and ''Challenger'' was cleared to launch at 11:38 a.m. EST, with an air temperature of .

Launch and failure

Liftoff and initial ascent

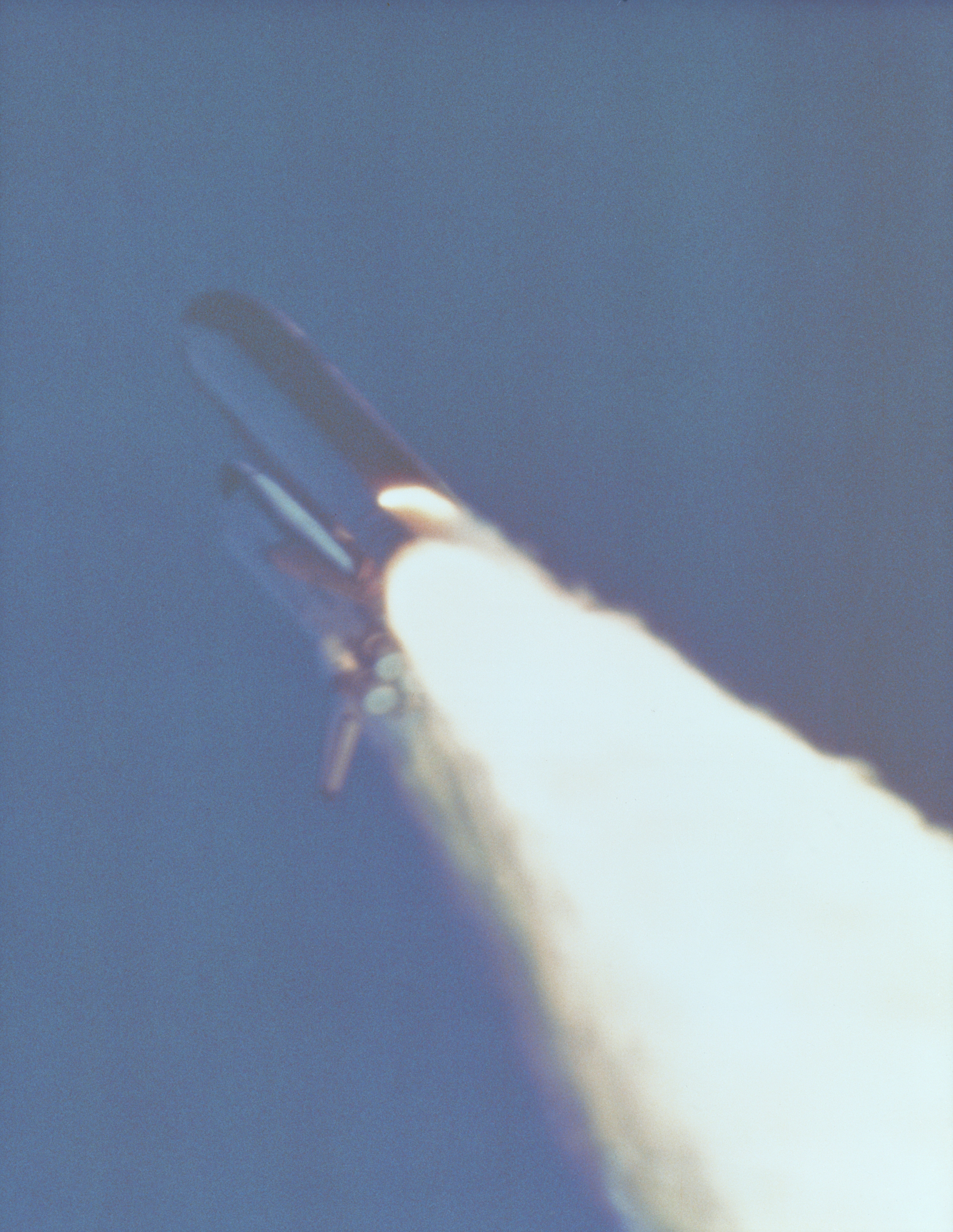

At T+0, ''Challenger'' launched from the

At T+0, ''Challenger'' launched from the Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39B

Launch Complex 39B (LC-39B) is the second of Launch Complex 39's three launch pads, located at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Merritt Island, Florida. The pad, along with Launch Complex 39A, was first designed for the Saturn V launch vehicle, ...

(LC-39B) at 11:38:00a.m. Beginning at T+0.678 until T+3.375 seconds, nine puffs of dark gray smoke were recorded escaping from the right-hand SRB near the aft strut that attached the booster to the ET. It was later determined that these smoke puffs were caused by joint rotation in the aft field joint of the right-hand SRB at ignition.

The cold temperature in the joint had prevented the O-rings from creating a seal. Rainfall from the preceding time on the launchpad had likely accumulated within the field joint, further compromising the sealing capability of the O-rings. As a result, hot gas was able to travel past the O-rings and erode them. Molten aluminum oxides from the burned propellant unintentionally resealed the joint and created a temporary barrier against further hot gas and flame escaping through the field joint. The Space Shuttle main engines

The RS-25, also known as the Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME), is a liquid-fuel cryogenic rocket engine that was used on NASA's Space Shuttle and is used on the Space Launch System.

Designed and manufactured in the United States by Rocketd ...

(SSMEs) were throttled down as scheduled for maximum dynamic pressure (max q). During its ascent, the Space Shuttle encountered wind shear

Wind shear (; also written windshear), sometimes referred to as wind gradient, is a difference in wind speed and/or direction over a relatively short distance in the atmosphere. Atmospheric wind shear is normally described as either vertical ...

conditions beginning at , but they were within design limits of the vehicle and were countered by the guidance system.

Plume

At , a tracking film camera captured the beginnings of a plume near the aft attach strut on the right SRB, right before the vehicle passed through max q at . The high aerodynamic forces and wind shear likely broke the unintentional aluminum oxide seal that had replaced eroded O-rings, allowing the flame to burn through the joint. Within one second from when it was first recorded, the plume became well-defined, and the enlarging hole caused a drop in internal pressure in the right SRB. A leak had begun in the

At , a tracking film camera captured the beginnings of a plume near the aft attach strut on the right SRB, right before the vehicle passed through max q at . The high aerodynamic forces and wind shear likely broke the unintentional aluminum oxide seal that had replaced eroded O-rings, allowing the flame to burn through the joint. Within one second from when it was first recorded, the plume became well-defined, and the enlarging hole caused a drop in internal pressure in the right SRB. A leak had begun in the liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen () is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecule, molecular H2 form.

To exist as a liquid, H2 must be cooled below its critical point (thermodynamics), critical point of 33 Kelvins, ...

(LH2) tank of the ET at , as indicated by the changing shape of the plume.

The SSMEs pivoted to compensate for the booster burn-through, which was creating an unexpected thrust on the vehicle. The pressure in the external LH2 tank began to drop at indicating that the flame had burned from the SRB into the tank. The crew and flight controllers made no indication they were aware of the vehicle and flight anomalies. At , the CAPCOM

is a Japanese video game company. It has created a number of critically acclaimed and List of best-selling video game franchises, multi-million-selling game franchises, with its most commercially successful being ''Resident Evil'', ''Monster ...

, Richard O. Covey

Richard Oswalt Covey (born August 1, 1946) is a retired United States Air Force officer, former NASA astronaut, and a member of the United States Astronaut Hall of Fame.

Early life

Born August 1, 1946, in Fayetteville, Arkansas, he considers ...

, told the crew, "''Challenger'', go at throttle up," indicating that the SSMEs had throttled up to 104% thrust. In response to Covey, Scobee said, "Roger, go at throttle up"; this was the last communication from ''Challenger'' on the air-to-ground loop.

Vehicle breakup

At , the right SRB pulled away from the aft strut that attached it to the ET, causing lateral acceleration that was felt by the crew. At the same time, pressure in the LH2 tank began dropping. Pilot Mike Smith said "Uh-oh," which was the last crew comment recorded. At , white vapor was seen flowing away from the ET, after which the aft dome of the LH2 tank fell off. The resulting release and ignition of all liquid hydrogen in the tank pushed the LH2 tank forward into the

At , the right SRB pulled away from the aft strut that attached it to the ET, causing lateral acceleration that was felt by the crew. At the same time, pressure in the LH2 tank began dropping. Pilot Mike Smith said "Uh-oh," which was the last crew comment recorded. At , white vapor was seen flowing away from the ET, after which the aft dome of the LH2 tank fell off. The resulting release and ignition of all liquid hydrogen in the tank pushed the LH2 tank forward into the liquid oxygen

Liquid oxygen, sometimes abbreviated as LOX or LOXygen, is a clear cyan liquid form of dioxygen . It was used as the oxidizer in the first liquid-fueled rocket invented in 1926 by Robert H. Goddard, an application which is ongoing.

Physical ...

(LOX) tank with a force equating to roughly , while the right SRB collided with the intertank structure. The failure of the LH2 and LOX tanks resulted in a type of explosion known as boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion

A boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE, ) is an explosion caused by the rupture of a Pressure vessel, vessel containing a Compressed fluid, pressurized liquid that has attained a temperature sufficiently higher than its boiling po ...

(BLEVE), one where a large part of the liquefied gas evaporates almost instantly.

These events resulted in an abrupt change to the shuttle stack's attitude and direction, which was shrouded from view by the vaporized contents of the now-destroyed ET. As it traveled at Mach

The Mach number (M or Ma), often only Mach, (; ) is a dimensionless quantity in fluid dynamics representing the ratio of flow velocity past a Boundary (thermodynamic), boundary to the local speed of sound.

It is named after the Austrian physi ...

1.92, ''Challenger'' took aerodynamic forces it was not designed to withstand and broke into several large pieces: a wing, the (still firing) main engines, the crew cabin and hypergolic fuel leaking from the ruptured reaction control system

A reaction control system (RCS) is a spacecraft system that uses Thrusters (spacecraft), thrusters to provide Spacecraft attitude control, attitude control and translation (physics), translation. Alternatively, reaction wheels can be used for at ...

were among the parts identified exiting the vapor cloud. The disaster unfolded at an altitude of . Both SRBs survived the breakup of the shuttle stack and continued flying, now unguided by the attitude and trajectory control of their mothership, until their flight termination systems were activated at .

Post-breakup flight controller dialogue

At , there was a burst of static on the air-to-ground loop as the vehicle broke up, which was later attributed to ground-based radios searching for a signal from the destroyed spacecraft. NASA Public Affairs Officer Steve Nesbitt was initially unaware of the explosion and continued to read out flight information. At , after video of the explosion was seen in Mission Control, the Ground Control Officer reported "negative contact (and) loss of

At , there was a burst of static on the air-to-ground loop as the vehicle broke up, which was later attributed to ground-based radios searching for a signal from the destroyed spacecraft. NASA Public Affairs Officer Steve Nesbitt was initially unaware of the explosion and continued to read out flight information. At , after video of the explosion was seen in Mission Control, the Ground Control Officer reported "negative contact (and) loss of downlink

In a telecommunications network, a link is a communication channel that connects two or more devices for the purpose of data transmission. The link may be a dedicated physical link or a virtual circuit that uses one or more physical links or shar ...

" as they were no longer receiving transmissions from ''Challenger''.

Nesbitt stated, "Flight controllers here are looking very carefully at the situation. Obviously a major malfunction. We have no downlink." Soon afterwards, he said, "We have a report from the Flight Dynamics Officer that the vehicle has exploded. The flight director confirms that. We are looking at checking with the recovery forces to see what can be done at this point."

In Mission Control, flight director Jay Greene ordered that contingency procedures be put into effect, which included locking the doors, shutting down telephone communications, and freezing computer terminals to collect data from them.Cause and time of death

The crew cabin, which was made of reinforced aluminum, separated in one piece from the rest of the orbiter. It then traveled in a ballistic arc, reaching the

The crew cabin, which was made of reinforced aluminum, separated in one piece from the rest of the orbiter. It then traveled in a ballistic arc, reaching the apogee

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. The line of apsides (also called apse line, or major axis of the orbit) is the line connecting the two extreme values.

Apsides perta ...

of approximately 25 seconds after the explosion. At the time of separation, the maximum acceleration is estimated to have been between 12 and 20 times that of gravity ( g). Within two seconds it had dropped below 4g, and within ten seconds the cabin was in free fall

In classical mechanics, free fall is any motion of a physical object, body where gravity is the only force acting upon it.

A freely falling object may not necessarily be falling down in the vertical direction. If the common definition of the word ...

. The forces involved at this stage were probably insufficient to cause major injury to the crew.

At least some of the crew were alive and conscious after the breakup, as Personal Egress Air Packs (PEAPs) were activated for Smith and two unidentified crewmembers, but not for Scobee. The PEAPs were not intended for in-flight use, and the astronauts never trained with them for an in-flight emergency. The location of Smith's activation switch, on the back side of his seat, indicated that either Resnik or Onizuka likely activated it for him. Investigators found their remaining unused air supply consistent with the expected consumption during the post-breakup trajectory.

While analyzing the wreckage, investigators discovered that several electrical system switches on Smith's right-hand panel had been moved from their usual launch positions. The switches had lever locks on top of them that must be pulled out before the switch could be moved. Later tests established that neither the force of the explosion nor the impact with the ocean could have moved them, indicating that Smith made the switch changes, presumably in a futile attempt to restore electrical power to the cockpit after the crew cabin detached from the rest of the orbiter.

On July 28, 1986, NASA's Associate Administrator for Space Flight, former astronaut Richard H. Truly, released a report on the deaths of the crew from physician and Skylab 2 astronaut Joseph P. Kerwin:

Pressurization could have enabled consciousness for the entire fall until impact. The crew cabin hit the ocean surface at approximately two minutes and 45 seconds after breakup. The estimated deceleration was , far exceeding structural limits of the crew compartment or crew survivability levels. The mid-deck floor had not suffered buckling or tearing, as would result from a rapid decompression, but stowed equipment showed damage consistent with decompression, and debris was embedded between the two forward windows that may have caused a loss of pressure. Impact damage to the crew cabin was severe enough that it could not be determined whether the crew cabin had previously been damaged enough to lose pressurization.

Prospect of crew escape

Unlike other spacecraft, the Space Shuttle did not allow for crew escape during powered flight. Launch escape systems had been considered during development, but NASA's conclusion was that the Space Shuttle's expected high reliability would preclude the need for one. Modified SR-71 Blackbird ejection seats and fullpressure suit

A pressure suit is a protective suit worn by high-altitude pilots who may fly at altitudes where the air pressure is too low for an unprotected person to survive, even when breathing pure oxygen at positive pressure. Such suits may be either fu ...

s were used for the two-person crews on the first four Space Shuttle orbital test flights, but they were disabled and later removed for the operational flights. Escape options for the operational flights were considered but not implemented due to their complexity, high cost, and heavy weight. After the disaster, a system was implemented to allow the crew to escape in gliding flight

Gliding flight is heavier-than-air flight without the use of thrust; the term volplaning also refers to this mode of flight in animals. It is employed by flying and gliding animals, gliding animals and by aircraft such as glider (aircraft), gl ...

, but this system would not have been usable to escape an explosion during ascent.

Recovery of debris and crew

Immediately after the disaster, the NASA Launch Recovery Director launched the two SRB recovery ships, MV ''Freedom Star'' and MV ''Liberty Star'', to proceed to the impact area to recover debris, and requested the support of US military aircraft and ships. Owing to falling debris from the explosion, the RSO kept recovery forces from the impact area until 12:37p.m. The size of the recovery operations increased to 12 aircraft and 8 ships by 7:00p.m. Surface operations recovered debris from the orbiter and external tank. The surface recovery operations ended on February7. On January31, theUS Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

was tasked with submarine recovery operations. The search efforts prioritized the recovery of the right SRB, followed by the crew compartment, and then the remaining payload, orbiter pieces, and ET. The search for debris formally began on February8 with the rescue and salvage ship , and eventually grew to sixteen ships, of which three were managed by NASA, four by the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, one by the US Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

and eight by independent contractors. The surface ships used side-scan sonar to make the initial search for debris and covered at water depths between and . The sonar operations discovered 881 potential locations for debris, of which 187 pieces were later confirmed to be from the orbiter.

The debris from the SRBs was widely distributed due to the detonation of their linear shaped charges. The identification of SRB material was primarily conducted by crewed submarines and submersibles. The vehicles were dispatched to investigate potential debris located during the search phase. Surface ships lifted the SRB debris with the help of technical divers and underwater remotely operated vehicles to attach the necessary slings to raise the debris with cranes. The solid propellant in the SRBs posed a risk, as it became more volatile after being submerged. Recovered portions of the SRBs were kept wet during recovery, and their unused propellant was ignited once they were brought ashore. The failed joint on the right SRB was first located on sonar on March1. Subsequent dives to by the submarine on April5 and the SEA-LINK I submersible on April12 confirmed that it was the damaged field joint, and it was successfully recovered on April13. Of the of both SRB shells, was recovered, another was found but not recovered, and was never found.

On March 7, Air Force divers identified potential crew compartment debris, which was confirmed the next day by divers from the USS ''Preserver''. The damage to the crew compartment indicated that it had remained largely intact during the initial explosion but was extensively damaged on impacting the ocean. The remains of the crew were badly damaged from impact and submersion, and were not intact bodies. The USS ''Preserver'' made multiple trips to return debris and remains to port, and continued crew compartment recovery until April4. During the recovery of the remains of the crew, Jarvis's body floated away and was not located until April15, several weeks after the other remains had been positively identified. Once remains were brought to port, pathologists from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology worked to identify the human remains, but could not determine the exact cause of death for any of them. Medical examiner

The medical examiner is an appointed official in some American jurisdictions who is trained in pathology and investigates deaths that occur under unusual or suspicious circumstances, to perform post-mortem examinations, and in some jurisdicti ...

s in Brevard County disputed the legality of transferring human remains to US military officials to conduct autopsies, and refused to issue the death certificates

A death certificate is either a legal document issued by a medical practitioner which states when a person died, or a document issued by a government civil registration office, that declares the date, location and cause of a person's death, as ...

; NASA officials ultimately released the death certificates of the crew members.

The IUS that would have been used to boost the orbit of the TDRS-B satellite was one of the first pieces of debris recovered. There was no indication that there had been premature ignition of the IUS, which had been one of the suspected causes for the disaster. Debris from the three SSMEs was recovered from February14 to28, and post-recovery analysis produced results consistent with functional engines suddenly losing their LH2 fuel supply. Deepwater recovery operations continued until April29, with smaller scale, shallow recovery operations continuing until August29. On December 17, 1996, two pieces of the orbiter were found at Cocoa Beach. On November 10, 2022, NASA announced that a piece of the shuttle had been found near the site of a destroyed World War II-era aircraft off the coast of Florida. The discovery was aired on the History Channel

History (formerly and commonly known as the History Channel) is an American pay television television broadcaster, network and the flagship channel of A&E Networks, a joint venture between Hearst Communications and the Disney General Entertainme ...

on November 22, 2022. Almost all recovered non-organic debris from ''Challenger'' is buried in Cape Canaveral Space Force Station

Cape Canaveral Space Force Station (CCSFS) is an installation of the United States Space Force's Space Launch Delta 45, located on Cape Canaveral in Brevard County, Florida.

Headquartered at the nearby Patrick Space Force Base, the sta ...

missile silo

A missile launch facility, also known as an underground missile silo, launch facility (LF), or nuclear silo, is a vertical cylindrical structure constructed underground, for the storage and launching of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM ...

s at LC-31 and LC-32.

Funeral ceremonies

On April 29, 1986, the astronauts' remains were transferred on a C-141 Starlifter aircraft from Kennedy Space Center to the military mortuary atDover Air Force Base

Dover Air Force Base or Dover AFB is a United States Air Force (USAF) base under the operational control of Air Mobility Command (AMC), located southeast of the city of Dover, Delaware. The 436th Airlift Wing is the host wing, and runs the bu ...

in Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

. Their caskets were each draped with an American flag and carried past an honor guard

A guard of honour (Commonwealth English), honor guard (American English) or ceremonial guard, is a group of people, typically drawn from the military, appointed to perform ceremonial duties – for example, to receive or guard a head of state ...

and followed by an astronaut escort. After the remains arrived at Dover Air Force Base, they were transferred to the families of the crew members. Scobee and Smith were buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

. Onizuka was buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

, Hawaii. McNair was buried in Rest Lawn Memorial Park in Lake City, South Carolina, but his remains were later moved within the town to the Dr. Ronald E. McNair Memorial Park. Resnik was cremated and her ashes were scattered over the water. McAuliffe was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Concord, New Hampshire

Concord () is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Hampshire and the county seat, seat of Merrimack County, New Hampshire, Merrimack County. As of the 2020 United States census the population was 43,976, making it the List of municipalities ...

. Jarvis was cremated, and his ashes were scattered in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

. Unidentified crew remains were buried at the Space Shuttle ''Challenger'' Memorial in Arlington on May 20, 1986.

Public response

White House response

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

had been scheduled to give the 1986 State of the Union Address on January28,1986, the evening of the ''Challenger'' disaster. After a discussion with his aides, Reagan postponed the State of the Union, and instead addressed the nation about the disaster from the Oval Office

The Oval Office is the formal working space of the president of the United States. Part of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, it is in the West Wing of the White House, in Washington, D.C.

The oval room has three lar ...

. On January31, Ronald and Nancy Reagan

Nancy Davis Reagan (; born Anne Frances Robbins; July 6, 1921 – March 6, 2016) was an American film actress who was the first lady of the United States from 1981 to 1989, as the second wife of President Ronald Reagan.

Reagan was born in ...

traveled to the Johnson Space Center to speak at a memorial service honoring the crew members. During the ceremony, an Air Force band sang "God Bless America

"God Bless America" is an American patriotic song written by Irving Berlin during World War I in 1918 and revised by him in the run-up to World War II in 1938. The later version was recorded by Kate Smith, becoming her signature song.

"Go ...

" as NASA T-38 Talon jets flew directly over the scene in the traditional missing-man formation.

Soon after the disaster, US politicians expressed concern that White House officials, including Chief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supportin ...

Donald Regan

Donald Thomas Regan (December 21, 1918 – June 10, 2003) was an American government official and business executive who served as the 66th United States secretary of the treasury from 1981 to 1985 and as the 11th White House chief of staff fr ...

and Communications Director

Director of communications is a position in both the private and public sectors. A director of communications is responsible for managing and directing an organization's internal and external communications. Directors of communications supervis ...

Pat Buchanan

Patrick Joseph Buchanan ( ; born November 2, 1938) is an American paleoconservative author, political commentator, and politician. He was an assistant and special consultant to U.S. presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan. He ...

, had pressured NASA to launch ''Challenger'' before the scheduled January 28 State of the Union address, because Reagan had planned to mention the launch in his remarks. In March 1986, the White House released a copy of the original State of the Union speech. In that speech, Reagan had intended to mention an X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

experiment launched on ''Challenger'' and designed by a guest he had invited to the address, but he did not further discuss the ''Challenger'' launch. In the rescheduled State of the Union address on February 4, Reagan mentioned the deceased ''Challenger'' crew members and modified his remarks about the X-ray experiment as "launched and lost". In April1986, the White House released a report that concluded there had been no pressure from the White House for NASA to launch ''Challenger'' prior to the State of the Union.

Media coverage

Nationally televised live coverage of the launch and explosion was provided byCNN

Cable News Network (CNN) is a multinational news organization operating, most notably, a website and a TV channel headquartered in Atlanta. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable ne ...

. To promote the Teacher in Space program with McAuliffe as a crewmember, NASA had arranged for many students in the US to view the launch live at school with their teachers. Other networks, such as CBS, soon cut in to their affiliate feeds to broadcast continuous coverage of the disaster and its aftermath. Press interest in the disaster increased in the following days; the number of reporters at KSC increased from 535 on the day of the launch to 1,467 reporters three days later. In the aftermath of the accident, NASA was criticized for not making key personnel available to the press. In the absence of information, the press published articles suggesting the external tank was the cause of the explosion. Archived by the Internet Archive on May 4, 2006. Until 2010, CNN's live broadcast was the only known footage filmed from the launch site. Additional amateur and professional recordings have since become publicly available. In the Soviet Union, footage of the disaster was played on the news, with coverage reflecting a tone that was described as being "somber and sympathetic" and "for the most part free of political overtones."

Engineering case study

The ''Challenger'' accident has been used as a case study for subjects such as engineering safety, the ethics ofwhistleblowing

Whistleblowing (also whistle-blowing or whistle blowing) is the activity of a person, often an employee, revealing information about activity within a private or public organization that is deemed illegal, immoral, illicit, unsafe, unethical or ...

, communications and group decision-making, and the dangers of groupthink

Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon that occurs within a group of people in which the desire for harmony or conformity in the group results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome. Cohesiveness, or the desire for cohesivenes ...

. Roger Boisjoly and Allan McDonald became speakers who advocated for responsible workplace decision making and engineering ethics. Information designer Edward Tufte

Edward Rolf Tufte (; born March 14, 1942), sometimes known as "ET",. is an American statistician and professor emeritus of political science, statistics, and computer science at Yale University. He is noted for his writings on information design ...

has argued that the ''Challenger'' accident was the result of poor communications and overly complicated explanations on the part of engineers, and stated that showing the correlation of ambient air temperature and O-ring erosion amounts would have been sufficient to communicate the potential dangers of the cold-weather launch. Boisjoly contested this assertion and stated that the data presented by Tufte were not as simple or available as Tufte stated.

Reports

Rogers Commission Report

The Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle ''Challenger'' Accident, also known as the Rogers Commission after its chairman, was formed on February6. Its members were Chairman William P. Rogers, Vice ChairmanNeil Armstrong

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an American astronaut and aerospace engineering, aeronautical engineer who, in 1969, became the Apollo 11#Lunar surface operations, first person to walk on the Moon. He was al ...

, David Acheson, Eugene Covert, Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of t ...

, Robert Hotz, Donald Kutyna, Sally Ride

Sally Kristen Ride (May 26, 1951 – July 23, 2012) was an American astronaut and physicist. Born in Los Angeles, she joined NASA in 1978, and in 1983 became the first American woman and the third woman to fly in space, after cosmonauts V ...

, Robert Rummel, Joseph Sutter, Arthur Walker, Albert Wheelon, and Chuck Yeager

Brigadier general (United States), Brigadier General Charles Elwood Yeager ( , February 13, 1923December 7, 2020) was a United States Air Force officer, flying ace, and record-setting test pilot who in October 1947 became the first pilot in his ...

.

The commission held hearings that discussed the NASA accident investigation, the Space Shuttle program, and the Morton Thiokol recommendation to launch despite O-ring safety issues. On February15, Rogers released a statement that established the commission's changing role to investigate the accident independent of NASA due to concerns of the failures of the internal processes at NASA. The commission created four investigative panels to research the different aspects of the mission. The Accident Analysis Panel, chaired by Kutyna, used data from salvage operations and testing to determine the exact cause behind the accident. The Development and Production Panel, chaired by Sutter, investigated the hardware contractors and how they interacted with NASA. The Pre-Launch Activities Panel, chaired by Acheson, focused on the final assembly processes and pre-launch activities conducted at KSC. The Mission Planning and Operations Panel, chaired by Ride, investigated the planning that went into mission development, along with potential concerns over crew safety and pressure to adhere to a schedule. Over a period of four months, the commission interviewed over 160 individuals, held at least 35 investigative sessions, and involved more than 6,000 NASA employees, contractors, and support personnel. The commission published its report on June 6, 1986.

The commission determined that the cause of the accident was hot gas blowing past the O-rings in the field joint on the right SRB, and found no other potential causes for the disaster. It attributed the accident to a faulty design of the field joint that was unacceptably sensitive to changes in temperature, dynamic loading, and the character of its materials. The report was critical of NASA and Morton Thiokol, and emphasized that both organizations had overlooked evidence that indicated the potential danger with the SRB field joints. It noted that NASA accepted the risk of O-ring erosion without evaluating how it could potentially affect the safety of a mission. The commission concluded that the safety culture and management structure at NASA were insufficient to properly report, analyze, and prevent flight issues. It stated that the pressure to increase the rate of flights negatively affected the amount of training, quality control, and repair work that was available for each mission.

The commission published a series of recommendations to improve the safety of the Space Shuttle program. It proposed a redesign of the joints in the SRB that would prevent gas from blowing past the O-rings. It also recommended that the program's management be restructured to keep project managers from being pressured to adhere to unsafe organizational deadlines, and should include astronauts to address crew safety concerns better. It proposed that an office for safety be established reporting directly to the NASA administrator to oversee all safety, reliability, and quality assurance functions in NASA programs. Additionally, the commission addressed issues with overall safety and maintenance for the orbiter, and it recommended the addition of the means for the crew to escape during controlled gliding flight.

During a televised hearing on February11, Feynman demonstrated the loss of rubber's elasticity in cold temperatures using a glass of cold water and a piece of rubber, for which he received media attention. Feynman, a

The commission determined that the cause of the accident was hot gas blowing past the O-rings in the field joint on the right SRB, and found no other potential causes for the disaster. It attributed the accident to a faulty design of the field joint that was unacceptably sensitive to changes in temperature, dynamic loading, and the character of its materials. The report was critical of NASA and Morton Thiokol, and emphasized that both organizations had overlooked evidence that indicated the potential danger with the SRB field joints. It noted that NASA accepted the risk of O-ring erosion without evaluating how it could potentially affect the safety of a mission. The commission concluded that the safety culture and management structure at NASA were insufficient to properly report, analyze, and prevent flight issues. It stated that the pressure to increase the rate of flights negatively affected the amount of training, quality control, and repair work that was available for each mission.

The commission published a series of recommendations to improve the safety of the Space Shuttle program. It proposed a redesign of the joints in the SRB that would prevent gas from blowing past the O-rings. It also recommended that the program's management be restructured to keep project managers from being pressured to adhere to unsafe organizational deadlines, and should include astronauts to address crew safety concerns better. It proposed that an office for safety be established reporting directly to the NASA administrator to oversee all safety, reliability, and quality assurance functions in NASA programs. Additionally, the commission addressed issues with overall safety and maintenance for the orbiter, and it recommended the addition of the means for the crew to escape during controlled gliding flight.

During a televised hearing on February11, Feynman demonstrated the loss of rubber's elasticity in cold temperatures using a glass of cold water and a piece of rubber, for which he received media attention. Feynman, a Nobel Prize