Sir Philip Sidney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Philip Sidney (30 November 1554 – 17 October 1586) was an English poet,

Sidney had returned to court by the middle of 1581. In the latter year he was elected to fill vacant seats in the

Sidney had returned to court by the middle of 1581. In the latter year he was elected to fill vacant seats in the

Later that year, he joined Sir John Norris in the

Later that year, he joined Sir John Norris in the

p. 216

/ref> This became possibly the most famous story about Sir Philip, intended to illustrate his noble and gallant character. Sidney's body was returned to London and interred in

Sidney's body was returned to London and interred in

*'' The Lady of May'' – This is one of Sidney's lesser-known works, a

*'' The Lady of May'' – This is one of Sidney's lesser-known works, a

The Poems of Sir Philip Sidney

ed. William A. Ringler. Oxford University Press, 1962. *'' The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia'', ed. Maurice Evans. Penguin Books, 1997. *'' The Sidney Psalms'', completed by Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, ed. R.E. Pritchard. Fyfield Books. Books *Alexander, Gavin. ''Writing After Sidney: the literary response to Sir Philip Sidney 1586–1640.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. *Allen, M. J. B. et al. ''Sir Philip Sidney's Achievements''. New York: AMS Press, 1990. *Craig, D. H. "A Hybrid Growth: Sidney's Theory of Poetry in ''An Apology for Poetry''." ''Essential Articles for the Study of Sir Philip Sidney.'' Ed. Arthur F. Kinney. Hamden: Archon Books, 1986. *Davies, Norman. '' Europe: A History''. London: Pimlico, 1997. *Duncan-Jones, Katherine. ''Sir Philip Sidney: Courtier Poet.'' New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1991. * Frye, Northrup. ''Words With Power: Being a Second Study of the Bible and Literature.'' Toronto: Penguin Books, 1992. *Garrett, Martin. Ed. ''Sidney: the Critical Heritage.'' London: Routledge, 1996. *Greville, Fulke.''Life of the Renowned Sir Philip Sidney''. London, 1652. *Hale, John. ''The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance''. New York: Atheeum, 1994. * Howell, Roger. ''Sir Philip Sidney: The Shepherd Knight''. London: Hutchinson, 1968. *Jasinski, James. ''Sourcebook on Rhetoric: Key Concepts in Contemporary Rhetorical Studies''. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2001. *Kimbrough, Robert. ''Sir Philip Sidney''. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1971. *Kuin, Roger (ed.), "The Correspondence of Sir Philip Sidney". 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. *Leitch, Vincent B., Ed. ''The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism''. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2001. *Lewis, C. S. ''English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Excluding Drama''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954. *Robertson, Jean. "Philip Sidney." In ''The Spenser Encyclopedia''. eds. A. C. Hamilton ''et al.'' Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990. *Shelley, Percy Bysshe. "A Defence of Poetry." In ''Shelley’s Poetry and Prose: A Norton Critical Edition''. 2nd ed. Eds. Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002. *Sidney, Philip. ''A Defence of Poesie and Poems''. London: Cassell and Company, 1891. *Van Dorsten, Jan, et al. ''Sir Philip Sidney: 1586 and the Creation of a Legend.'' Leiden: Brill, 1986. * Woudhuysen, H. R., ''Sir Philip Sidney and the Circulation of Manuscripts, 1558-1640'', Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996 *''The Cambridge History of English and American Literature''. Volume 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. *Pears, Steuart A.,

The Correspondence of Sir Philip Sidney and Hubert Languet

', subtitled ''now first collected and translated from the latin with notes and a memoir of Sidney'', Wiliam Pickering, London, 1845; Gregg International Publishers, Ltd., Farnborough, 1971: (Pears, Steuart Adolphus). *Bradley, William Aspenwall, Ed.

The Correspondence of Philip Sidney and Hubert Languet

' (The Humanist's Library V, Einstein, Lewis, Ed.), The Merrymount Press, Boston, 1912. (also includes two letters from Sidney to his brother Robert and biographical notes) Articles *Acheson, Kathy.

: Anti-Theatricality and Gender in Early Modern Closet Drama by Women." ''Early Modern Literary Studies'' 6.3 (January, 2001): 7.1–16. 21 October 2005. *Bear, R. S.

In ''Renascence Editions.'' 21 October 2005. *Griffiths, Matthew

25 November 2005. *Harvey, Elizabeth D

. In ''The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory & Criticism''. 25 November 2005. *Knauss, Daniel, Philip

, Master's Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the

Cultural Materialism and New Historicism.

8 November 2005 *Mitsi, Efterpi

In ''Early Modern Literary Studies''. 9 November 2004. *Pask, Kevin

25 November 2005. *Staff. ttp://www.poetsgraves.co.uk/sidney.htm Sir Philip Sidney 1554–1586 Poets' Graves. Accessed 26 May 2008 Other *Stump, Donald (ed)

"Sir Philip Sidney: World Bibliography

The Correspondence of Philip Sidney

i

EMLO

* * * Audio

Robert Pinsky reads "My True Love Hath My Heart and I Have His"

by Philip Sidney (vi

poemsoutloud.net

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sidney, Philip 16th-century English knights 16th-century English poets

courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the officia ...

, scholar and soldier who is remembered as one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan age.

His works include a sonnet sequence, '' Astrophil and Stella'', a treatise

A treatise is a Formality, formal and systematic written discourse on some subject concerned with investigating or exposing the main principles of the subject and its conclusions."mwod:treatise, Treatise." Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Acc ...

, '' The Defence of Poesy'' (also known as ''The Defence of Poesie'' or ''An Apology for Poetrie'') and a pastoral romance, '' The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia''. He died fighting the Spanish in the Netherlands, age 31, and his funeral procession in London was one of the most lavish ever seen.

Biography

Early life

Born at Penshurst Place,Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, of an aristocratic family, he was educated at Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by royal charter, to replace the town's Saxon collegiate foundations which were disestablished in the sixteenth century, Shrewsb ...

and Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

. He was the eldest son of Sir Henry Sidney and Lady Mary Dudley. His mother was the eldest daughter of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, and the sister of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Dudley's youth was ove ...

.

His sister, Mary, was a writer, translator and literary patron, and married Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke. Sidney dedicated his longest work, the '' Arcadia'', to her. After her brother's death, Mary reworked the ''Arcadia'', which became known as ''The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia''.

His brother Robert Sidney was a statesman and patron of the arts, and was created Earl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester is a title that has been created seven times. The first title was granted during the 12th century in the Peerage of England. The current title is in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and was created in 1837.

History

Earl ...

in 1618.

Politics and marriage

In 1572, at the age of 18, he travelled to France as part of the embassy to negotiate a marriage betweenElizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

and the Duc D'Alençon. He spent the next several years in mainland Europe, moving through Germany, Italy, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

and Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

. On these travels, he met a number of prominent European intellectuals and politicians.

Returning to England in 1575, Sidney met Penelope Devereux (who would later marry Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick). Although much younger, she inspired his famous sonnet sequence of the 1580s, '' Astrophel and Stella.'' Her father, Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex (16 September 1539 – 22 September 1576), was an English nobleman and general. From 1573 until his death he fought in Ireland in connection with the Plantations of Ireland, most notably the Rathlin Island ...

, was said to have planned to marry his daughter to Sidney, but Walter died in 1576 and this did not occur. In England, Sidney occupied himself with politics and art. He defended his father's administration of Ireland in a lengthy document.

More seriously, he quarrelled with Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (; 12 April 155024 June 1604), was an English peerage, peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after ...

, probably because of Sidney's opposition to the French marriage of Elizabeth to the much younger Alençon, which de Vere championed. In the aftermath of this episode, Sidney challenged de Vere to a duel, which Elizabeth forbade. He then wrote a lengthy letter to the Queen detailing the foolishness of the French marriage. Characteristically, Elizabeth bristled at his presumption, and Sidney prudently retired from court.

During a 1577 diplomatic visit to Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, Sidney secretly visited the exiled Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priest Edmund Campion.

Sidney had returned to court by the middle of 1581. In the latter year he was elected to fill vacant seats in the

Sidney had returned to court by the middle of 1581. In the latter year he was elected to fill vacant seats in the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the Great Council of England, great council of Lords Spi ...

for both Ludlow

Ludlow ( ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is located south of Shrewsbury and north of Hereford, on the A49 road (Great Britain), A49 road which bypasses the town. The town is near the conf ...

and Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is sited on the River Severn, northwest of Wolverhampton, west of Telford, southeast of Wrexham and north of Hereford. At the 2021 United ...

, choosing to sit for the latter, and in 1584 was MP for Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

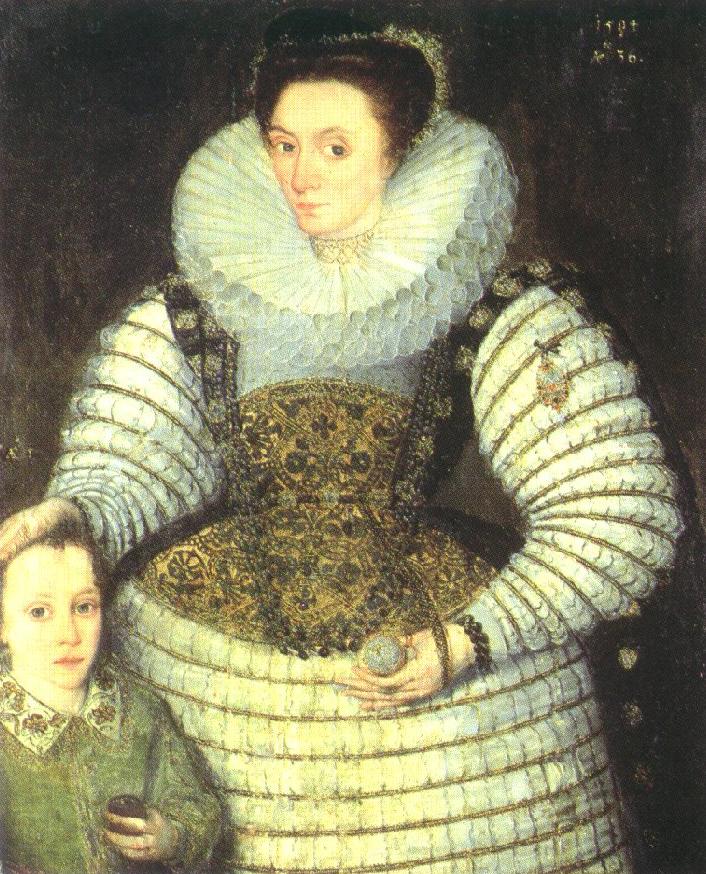

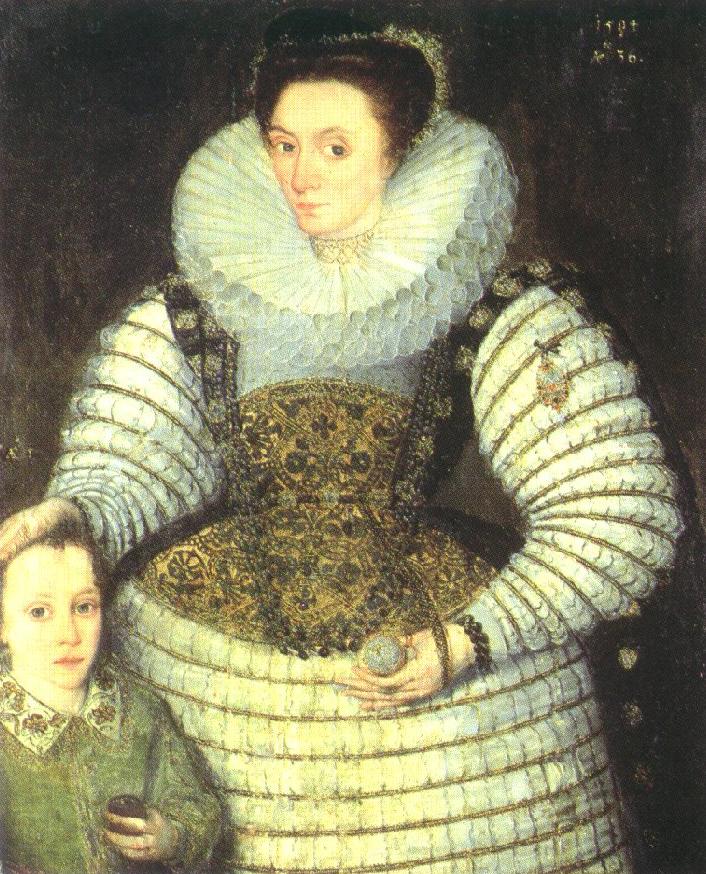

. That same year Penelope Devereux was married, apparently against her will, to Lord Rich. Sidney was knighted in 1583. An early arrangement to marry Anne Cecil, daughter of Sir William Cecil and eventual wife of de Vere, had fallen through in 1571. In 1583, he married Frances

Frances is an English given name or last name of Latin origin. In Latin the meaning of the name Frances is 'from France' or 'the French.' The male version of the name in English is Francis (given name), Francis. The original Franciscus, meaning "F ...

, the 16-year-old daughter of Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her " spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wa ...

. In the same year, he made a visit to Oxford University with Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno ( , ; ; born Filippo Bruno; January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which concep ...

, the polymath known for his cosmological theories, who subsequently dedicated two books to Sidney.

In 1585 the couple had one daughter, Elizabeth, who later married Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland, in March 1599 and died without issue in 1612.

Literary writings

Like the best of the Elizabethans, Sidney was successful in more than one branch of literature, but none of his work was published during his lifetime. However, it circulated in manuscript. His finest achievement was a sequence of 108 love sonnets. These owe much toPetrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

and Pierre de Ronsard

Pierre de Ronsard (; 11 September 1524 – 27 December 1585) was a French poet known in his generation as a "Prince des poètes, prince of poets". His works include ''Les Amours de Cassandre'' (1552)'','' ''Les Hymnes'' (1555-1556)'', Les Disco ...

in tone and style, and place Sidney as the greatest Elizabethan sonneteer after Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

. Written to his mistress, Lady Penelope Rich, though dedicated to his wife, they reveal true lyric emotion couched in a language delicately archaic. In form Sidney usually adopts the Petrarchan octave

In music, an octave (: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is an interval between two notes, one having twice the frequency of vibration of the other. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been referr ...

(ABBAABBA), with variations in the sestet that include the English final couplet. His artistic contacts were more peaceful and significant for his lasting fame. During his absence from court, he wrote '' Astrophel and Stella'' (1591) and the first draft of ''The Arcadia'' and '' The Defence of Poesy''. Somewhat earlier, he had met Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; – 13 January 1599 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the House of Tudor, Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is re ...

, who dedicated '' The Shepheardes Calender'' to him. Other literary contacts included membership, along with his friends and fellow poets Fulke Greville, Edward Dyer, Edmund Spenser and Gabriel Harvey, of the (possibly fictitious) "Areopagus

The Areopagus () is a prominent rock outcropping located northwest of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. Its English name is the Late Latin composite form of the Greek name Areios Pagos, translated "Hill of Ares" (). The name ''Areopagus'' also r ...

", a humanist endeavour to classicise English verse.

Military activity

Sidney played a brilliant part in the military/literary/courtly life common to the young nobles of the time. Both his family heritage and his personal experience (he was in Walsingham's house in Paris during the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre), confirmed him as a keenly militant Protestant. In the 1570s, he persuaded John Casimir to consider proposals for a united Protestant effort against the Catholic Church and Spain. In the winter of 1575-76 he fought in Ireland while his father was Lord Deputy there. In the early 1580s, he argued fruitlessly for an assault on Spain itself. Promoted General of Horse in 1583, his enthusiasm for the Protestant struggle was given free rein when he was appointed governor of Flushing in the Netherlands in 1585. Whilst in the Netherlands, he consistently urged boldness on his superior, his uncle theEarl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester is a title that has been created seven times. The first title was granted during the 12th century in the Peerage of England. The current title is in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and was created in 1837.

History

Earl ...

. He carried out a successful raid on Spanish forces near Axel in July 1586.

Injury and death

Battle of Zutphen

The Battle of Zutphen was fought on 22 September 1586, near the village of Warnsveld and the town of Zutphen, the Netherlands, during the Eighty Years' War. It was fought between the forces of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, aided ...

, fighting for the Protestant cause against the Spanish.The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Sixteenth/Early Seventeenth Century, Volume B, 2012, pg. 1037 During the battle, he was shot in the thigh and died of gangrene 26 days later, at the age of 31. One account says this death was avoidable and heroic. Sidney noticed that one of his men was not fully armoured. He took off his thigh armour on the grounds that it would be wrong to be better armored than his men. As he lay dying, Sidney composed a song to be sung by his deathbed. According to the story, while lying wounded he gave his water to another wounded soldier, saying, "Thy necessity is yet greater than mine".Charles Carlton (1992). ''Going to the Wars: The Experience of the British Civil Wars, 1638–1651'', Routledge, p. 216

/ref> This became possibly the most famous story about Sir Philip, intended to illustrate his noble and gallant character.

Sidney's body was returned to London and interred in

Sidney's body was returned to London and interred in Old St Paul's Cathedral

Old St Paul's Cathedral was the cathedral of the City of London that, until the Great Fire of London, Great Fire of 1666, stood on the site of the present St Paul's Cathedral. Built from 1087 to 1314 and dedicated to Paul of Tarsus, Saint Paul ...

on 16 February 1587. The grave and monument were destroyed in the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Wednesday 5 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old London Wall, Roman city wall, while also extendi ...

in 1666. A modern monument in the crypt lists his among the important graves lost.

Already during his own lifetime, but even more after his death, he had become for many English people the very epitome of a Castiglione courtier: learned and politic, but at the same time generous, brave, and impulsive. The funeral procession was one of the most elaborate ever staged, so much so that his father-in-law, Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her " spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wa ...

, almost went bankrupt. As Sidney was a brother of the Worshipful Company of Grocers, the procession included 120 of his company brethren.

Never more than a marginal figure in the politics of his time, he was memorialised as the flower of English manhood in Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; – 13 January 1599 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the House of Tudor, Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is re ...

's '' Astrophel'', one of the greatest English Renaissance elegies.

An early biography of Sidney was written by his devoted friend and schoolfellow, Fulke Greville. While Sidney was traditionally depicted as a staunch and unwavering Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

, recent biographers such as Katherine Duncan-Jones

Katherine Dorothea Duncan-Jones (13 May 1941 – 16 October 2022) was an English literature and Shakespeare scholar and was also a Fellow of New Hall, Cambridge (1965–1966), and then Somerville College, Oxford (1966–2001). She was also Prof ...

have suggested that his religious loyalties were more ambiguous. He was known to be friendly and sympathetic towards individual Catholics.

Works

*'' The Lady of May'' – This is one of Sidney's lesser-known works, a

*'' The Lady of May'' – This is one of Sidney's lesser-known works, a masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A mas ...

written and performed for Queen Elizabeth in 1578 or 1579.

*'' Astrophil and Stella'' – The first of the famous English sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

sequences, ''Astrophil and Stella'' was probably composed in the early 1580s. The sonnets were well-circulated in manuscript before the first (apparently pirated) edition was printed in 1591; only in 1598 did an authorised edition reach the press. The sequence was a watershed in English Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

poetry. In it, Sidney partially nativised the key features of his Italian model, Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

: variation of emotion from poem to poem, with the attendant sense of an ongoing, but partly obscure, narrative; the philosophical trappings; the musings on the act of poetic creation itself. His experiments with rhyme scheme

A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes at the end of each line of a poem or song. It is usually referred to by using letters to indicate which lines rhyme; lines designated with the same letter all rhyme with each other.

An example of the ABAB rh ...

were no less notable; they served to free the English sonnet from the strict rhyming requirements of the Italian form.

*'' The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia'' – The ''Arcadia'', by far Sidney's most ambitious work, was as significant in its own way as his sonnets. The work is a romance that combines pastoral

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target au ...

elements with a mood derived from the Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

model of Heliodorus. In the work, that is, a highly idealised version of the shepherd's life adjoins (not always naturally) with stories of joust

Jousting is a medieval and renaissance martial game or hastilude between two combatants either on horse or on foot. The joust became an iconic characteristic of the knight in Romantic medievalism.

The term is derived from Old French , ultim ...

s, political treachery, kidnapping

Kidnapping or abduction is the unlawful abduction and confinement of a person against their will, and is a crime in many jurisdictions. Kidnapping may be accomplished by use of force or fear, or a victim may be enticed into confinement by frau ...

s, battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force co ...

s, and rapes. As published in the sixteenth century, the narrative follows the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

model: stories are nested within each other, and different storylines are intertwined. The work enjoyed great popularity for more than a century after its publication. William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

borrowed from it for the Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city, non-metropolitan district and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West England, South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean ...

subplot of ''King Lear

''The Tragedy of King Lear'', often shortened to ''King Lear'', is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare. It is loosely based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his ...

''; parts of it were also dramatised by John Day and James Shirley

James Shirley (or Sherley) (September 1596 – October 1666) was an English dramatist.

He belonged to the great period of English dramatic literature, but, in Charles Lamb (writer), Charles Lamb's words, he "claims a place among the worthies of ...

. According to a widely told story, King Charles I quoted lines from the book as he mounted the scaffold to be executed; Samuel Richardson named the heroine of his first novel '' Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' after Sidney's Pamela. ''Arcadia'' exists in two significantly different versions. Sidney wrote an early version (the ''Old Arcadia'') during a stay at Mary Herbert's house; this version is narrated in a straightforward, sequential manner. Later, Sidney began to revise the work on a more ambitious plan, with much more backstory about the princes, and a much more complicated story-line, with many more characters. He completed most of the first three books, but the project was unfinished at the time of his death – the third book breaks off in the middle of a sword fight. There were several early editions of the book. Fulke Greville published the revised version alone, in 1590. The Countess of Pembroke, Sidney's sister, published a version in 1593, which pasted the last two books of the first version onto the first three books of the revision. In the 1621 version, Sir William Alexander provided a bridge to bring the two stories back into agreement. It was known in this cobbled-together fashion until the discovery, in the early twentieth century, of the earlier version.

*''An Apology for Poetry

''An Apology for Poetry'' (or ''The Defence of Poesy'') is a work of literary criticism by Elizabethan poetry, Elizabethan poet Philip Sidney. It was written in approximately 1580 and first published in 1595, after his death.

It is generally b ...

'' (also known as ''A Defence of Poesie'' and ''The Defence of Poetry'') – Sidney wrote ''Defence of Poetry'' before 1583. It has taken its place among the great critical essays in English. It is generally believed that he was at least partly motivated by Stephen Gosson, a former playwright who dedicated his attack on the English stage, ''The School of Abuse'', to Sidney in 1579, but Sidney primarily addresses more general objections to poetry, such as those of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

. In his essay, Sidney integrates a number of classical and Italian precepts on fiction. The essence of his defence is that poetry, by combining the liveliness of history with the ethical focus of philosophy, is more effective than either history or philosophy in rousing its readers to virtue. The work also offers important comments on Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; – 13 January 1599 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the House of Tudor, Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is re ...

and the Elizabethan stage.

*'' The Sidney Psalms'' – These English translations of the Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( , ; ; ; ; , in Islam also called Zabur, ), also known as the Psalter, is the first book of the third section of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) called ('Writings'), and a book of the Old Testament.

The book is an anthology of B ...

were completed in 1599 by Philip Sidney's sister Mary.

In popular culture

A memorial, erected in 1986 at the location in Zutphen where he was mortally wounded by the Spanish, can be found at the entrance of a footpath (" 't Gallee") located in front of the petrol station at the Warnsveldseweg 170. InArnhem

Arnhem ( ; ; Central Dutch dialects, Ernems: ''Èrnem'') is a Cities of the Netherlands, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands, near the German border. It is the capita ...

, in front of the house in the Bakkerstraat 68, an inscription on the ground reads: "IN THIS HOUSE DIED ON THE 17 OCTOBER 1586 * SIR PHILIP SIDNEY * ENGLISH POET, DIPLOMAT AND SOLDIER, FROM HIS WOUNDS SUFFERED AT THE BATTLE OF ZUTPHEN. HE GAVE HIS LIFE FOR OUR FREEDOM". The inscription was unveiled on 17 October 2011, exactly 425 years after his death, in the presence of Philip Sidney, 2nd Viscount De L'Isle, a descendant of the brother of Philip Sidney.

The city of Sidney, Ohio

Sidney is a city in Shelby County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. The population was 20,421 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is approximately north of Dayton, Ohio, Dayton and south of Toledo, Ohio, Toledo, and is a ...

, in the United States and a street in Zutphen, Netherlands, have been named after Sir Philip. A statue of him can be found in the park at the Coehoornsingel where, in the harsh winter of 1795, English and Hanoverian soldiers were buried who had died while retreating from advancing French troops.

Another statue of Sidney, by Arthur George Walker, forms the centrepiece of the Old Salopians Memorial at Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by royal charter, to replace the town's Saxon collegiate foundations which were disestablished in the sixteenth century, Shrewsb ...

to alumni who died serving in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

(unveiled 1924).

Philip Sidney appears as a young man in Elizabeth Goudge's third novel, ''Towers in the Mist'' (Duckworth, 1937), visiting Oxford around the time Queen Elizabeth also visited Oxford. (Goudge admitted to slightly advancing the time of Sidney's arrival in Oxford, for the sake of her larger story.)

In the ''Monty Python's Flying Circus

''Monty Python's Flying Circus'' (also known as simply ''Monty Python'') is a British surreal humour, surreal sketch comedy series created by and starring Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, Michael Palin, and Terry Gilliam, w ...

'' sketches "Tudor Jobs Agency", "Pornographic Bookshop" and "Elizabethan Pornography Smugglers" (Season 3, episode 10), Superintendent Gaskell, a vice squad

Vice Squad are an English punk rock band formed in 1979 in Bristol. The band was formed from two other local punk bands, The Contingent and TV Brakes. The songwriter and vocalist Beki Bondage (born Rebecca Bond) was a founding member of the b ...

policeman, is transported back to the Elizabethan age and assumes Sir Philip Sidney's identity.

An epitaph of Sir Philip Sidney:

"England has his body, for she it fed;

Netherlands his blood, in her defence shed;

The Heavens have his soul,

The Arts have his fame,

The soldier his grief,

The world his good name."The Wayfarer's Book(1952) . By E.Mansell (2011 reprint "The Rambler's Countryside Companion") p. 172

References

Further reading

WorksThe Poems of Sir Philip Sidney

ed. William A. Ringler. Oxford University Press, 1962. *'' The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia'', ed. Maurice Evans. Penguin Books, 1997. *'' The Sidney Psalms'', completed by Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, ed. R.E. Pritchard. Fyfield Books. Books *Alexander, Gavin. ''Writing After Sidney: the literary response to Sir Philip Sidney 1586–1640.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. *Allen, M. J. B. et al. ''Sir Philip Sidney's Achievements''. New York: AMS Press, 1990. *Craig, D. H. "A Hybrid Growth: Sidney's Theory of Poetry in ''An Apology for Poetry''." ''Essential Articles for the Study of Sir Philip Sidney.'' Ed. Arthur F. Kinney. Hamden: Archon Books, 1986. *Davies, Norman. '' Europe: A History''. London: Pimlico, 1997. *Duncan-Jones, Katherine. ''Sir Philip Sidney: Courtier Poet.'' New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1991. * Frye, Northrup. ''Words With Power: Being a Second Study of the Bible and Literature.'' Toronto: Penguin Books, 1992. *Garrett, Martin. Ed. ''Sidney: the Critical Heritage.'' London: Routledge, 1996. *Greville, Fulke.''Life of the Renowned Sir Philip Sidney''. London, 1652. *Hale, John. ''The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance''. New York: Atheeum, 1994. * Howell, Roger. ''Sir Philip Sidney: The Shepherd Knight''. London: Hutchinson, 1968. *Jasinski, James. ''Sourcebook on Rhetoric: Key Concepts in Contemporary Rhetorical Studies''. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2001. *Kimbrough, Robert. ''Sir Philip Sidney''. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1971. *Kuin, Roger (ed.), "The Correspondence of Sir Philip Sidney". 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. *Leitch, Vincent B., Ed. ''The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism''. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2001. *Lewis, C. S. ''English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Excluding Drama''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954. *Robertson, Jean. "Philip Sidney." In ''The Spenser Encyclopedia''. eds. A. C. Hamilton ''et al.'' Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990. *Shelley, Percy Bysshe. "A Defence of Poetry." In ''Shelley’s Poetry and Prose: A Norton Critical Edition''. 2nd ed. Eds. Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002. *Sidney, Philip. ''A Defence of Poesie and Poems''. London: Cassell and Company, 1891. *Van Dorsten, Jan, et al. ''Sir Philip Sidney: 1586 and the Creation of a Legend.'' Leiden: Brill, 1986. * Woudhuysen, H. R., ''Sir Philip Sidney and the Circulation of Manuscripts, 1558-1640'', Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996 *''The Cambridge History of English and American Literature''. Volume 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. *Pears, Steuart A.,

The Correspondence of Sir Philip Sidney and Hubert Languet

', subtitled ''now first collected and translated from the latin with notes and a memoir of Sidney'', Wiliam Pickering, London, 1845; Gregg International Publishers, Ltd., Farnborough, 1971: (Pears, Steuart Adolphus). *Bradley, William Aspenwall, Ed.

The Correspondence of Philip Sidney and Hubert Languet

' (The Humanist's Library V, Einstein, Lewis, Ed.), The Merrymount Press, Boston, 1912. (also includes two letters from Sidney to his brother Robert and biographical notes) Articles *Acheson, Kathy.

: Anti-Theatricality and Gender in Early Modern Closet Drama by Women." ''Early Modern Literary Studies'' 6.3 (January, 2001): 7.1–16. 21 October 2005. *Bear, R. S.

In ''Renascence Editions.'' 21 October 2005. *Griffiths, Matthew

25 November 2005. *Harvey, Elizabeth D

. In ''The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory & Criticism''. 25 November 2005. *Knauss, Daniel, Philip

, Master's Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the

North Carolina State University

North Carolina State University (NC State, North Carolina State, NC State University, or NCSU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Raleigh, North Carolina, United States. Founded in 1887 and p ...

. 25 November 2005.

* Maley, WillyCultural Materialism and New Historicism.

8 November 2005 *Mitsi, Efterpi

In ''Early Modern Literary Studies''. 9 November 2004. *Pask, Kevin

25 November 2005. *Staff. ttp://www.poetsgraves.co.uk/sidney.htm Sir Philip Sidney 1554–1586 Poets' Graves. Accessed 26 May 2008 Other *Stump, Donald (ed)

"Sir Philip Sidney: World Bibliography

Saint Louis University

Saint Louis University (SLU) is a private university, private Society of Jesus, Jesuit research university in St. Louis, Missouri, United States. Founded in 1818 by Louis William Valentine DuBourg, it is the oldest university west of the Missi ...

. Accessed 26 May 2008. "This site is the largest collection of bibliographic references on Sidney in existence. It includes all the items originally published in ''Sir Philip Sidney: An Annotated Bibliography of Texts and Criticism, 1554–1984'' (New York: G.K. Hall, Macmillan 1994) as well updates from 1985 to the present."

External links

*The Correspondence of Philip Sidney

i

EMLO

* * * Audio

Robert Pinsky reads "My True Love Hath My Heart and I Have His"

by Philip Sidney (vi

poemsoutloud.net

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sidney, Philip 16th-century English knights 16th-century English poets

Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male name derived from the Macedonian Old Koine language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominen ...

Sonneteers

1554 births

1586 deaths

English courtiers

16th-century English diplomats

16th-century English soldiers

16th-century English novelists

16th-century English male writers

People of the Elizabethan era

People educated at Shrewsbury School

People from Penshurst

English military personnel killed in action

English people of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604)

Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford

Ambassadors of England to the Dutch Republic

Deaths from gangrene

English MPs 1572–1583

English MPs 1584–1585

English male poets

English male novelists

Burials at St Paul's Cathedral

Court of Elizabeth I

Knights Bachelor

English LGBTQ politicians