Silbannacus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Silbannacus was an obscure Roman emperor or usurper during the

It is not clear from the coins alone when Silbannacus would have been active. In 1940, the British

It is not clear from the coins alone when Silbannacus would have been active. In 1940, the British

The style of the second coin of Silbannacus appears to copy the design used on the coins of the emperor Aemilian (253), which suggests that Silbannacus ruled later than the time of Philip, possibly around the time of Aemilian's short reign. In particular, both the bust of Silbannacus on the coin, as well as the legend MARTI PROPVGT appears very similar to Aemilian's coins. The similarity might suggest that the coins were made in the same mint, which would mean that Silbannacus held brief control of the mint in the imperial capital.

253 was a turbulent year and many of the events that took place are obscure due to a lack of surviving sources. Aemilian's predecessor was

The style of the second coin of Silbannacus appears to copy the design used on the coins of the emperor Aemilian (253), which suggests that Silbannacus ruled later than the time of Philip, possibly around the time of Aemilian's short reign. In particular, both the bust of Silbannacus on the coin, as well as the legend MARTI PROPVGT appears very similar to Aemilian's coins. The similarity might suggest that the coins were made in the same mint, which would mean that Silbannacus held brief control of the mint in the imperial capital.

253 was a turbulent year and many of the events that took place are obscure due to a lack of surviving sources. Aemilian's predecessor was

Philip the Arab and Rival Claimants of the later 240s

. Retrieved 2021-04-11. * * {{Roman Emperors 3rd-century deaths 3rd-century Roman usurpers 3rd-century Roman emperors Year of birth unknown Year of death unknown Ancient Romans from unknown gentes Crisis of the Third Century

Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis, was a period in History of Rome, Roman history during which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressure of repeated Barbarian invasions ...

. Silbannacus is not mentioned in any contemporary documents and his existence was forgotten until the 20th century, when two coins bearing his name were discovered, the first in the 1930s and the second in the 1980s. His unusual name suggests that he might have been of Gallic descent.

As the only known evidence for his existence is the two coins, the exact time and extent of Silbannacus's rule is not known. Based on the design of the coin and its silver content, Silbannacus was most likely concurrent with the reigns of Philip the Arab

Philip I (; – September 249), commonly known as Philip the Arab, was Roman emperor from 244 to 249. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Philip, who had been Praetorian prefect, rose to power. He quickly negotiated peace with the S ...

(244–249), Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Trajanus Decius ( 201June 251), known as Trajan Decius or simply Decius (), was Roman emperor from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was proclaimed emperor by his troops a ...

(249–251), Trebonianus Gallus

Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus ( 206 – August 253) was Roman emperor from June 251 to August 253, in a joint rule with his son Volusianus.

Early life

Gallus was born in Italy, in a respected senatorial family with Etruscan ancestry, cer ...

(251–253), Aemilian (253), or Valerian (253–260). The two most prevalent ideas are the older hypothesis, that Silbannacus was a usurper in Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

during the reign of Philip the Arab, at some point between 248 and 250, and the newer hypothesis, based on the design of the second coin, that Silbannacus was a briefly reigning legitimate emperor, holding Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

between the death of Aemilian and the arrival of Valerian.

Name

The coins of Silbannacus give him the style ''Imperator Mar. Silbannacus Augustus''. Per the German historian Felix Hartmann, writing in 1982, and the English historian Maxwell Craven, writing in 2019, the unusual name Silbannacus appears to be of Celtic origin, due to the suffix "-acus", suggesting that Silbannacus might have been of Gallic, or perhaps evenBritish

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

, descent. Another possibility is that Silbannacus is a misspelling of Silvannacus or Silvaniacus, names derived from the Roman forest god Silvanus. Silvanus might have been based on the Etruscan god Selvans, which could suggest Silbannacus as originating from central Italy (the homeland of the Etruscans). Otherwise, northern Italy had Celto-Gallic influences, an alternate explanation of the suffix "-acus", which suggest a northern Italian origin. The name being misspelled is possible, as there exist known examples of misspellings on coins of other emperors: some of the coins of Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (; Ancient Greek, Greek: Λικίνιος; c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign, he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan that ...

(308–324) refer to him as "Licinnius" and some of the coins of Vetranio (350) refer to him as "Vertanio".

As there were several common Roman names that began with Mar., the correct reading of his '' nomen'' is not certain. Though some modern reference works refer to him as "Marcus Silbannacus", Marcus was typically a ''praenomen

The praenomen (; plural: praenomina) was a first name chosen by the parents of a Ancient Rome, Roman child. It was first bestowed on the ''dies lustricus'' (day of lustration), the eighth day after the birth of a girl, or the ninth day after the ...

'', unlikely to be featured on coins in this period. More likely readings, according to Craven "the only likely alternatives", are either Marcius or Marius. Additionally, the German historian Christian Körner suggested the name Marinus as a third possibility in 2002. If his ''nomen'' was Marcius, Craven considers it possible that he could have been related to Marcia Otacilia Severa, the wife and empress of Emperor Philip the Arab

Philip I (; – September 249), commonly known as Philip the Arab, was Roman emperor from 244 to 249. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Philip, who had been Praetorian prefect, rose to power. He quickly negotiated peace with the S ...

(244–249).

Interpretations and speculation

Both coins of Silbannacus were found in what was onceGaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

; the first coin was discovered in the 1930s, reputedly in Lorraine and the second coin was found in the 1980s somewhere near Paris. The Lorraine coin was acquired by the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

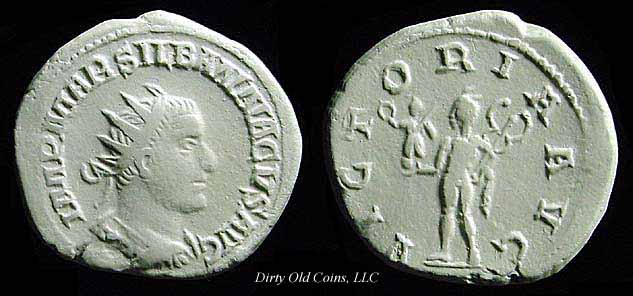

in 1937 from a Swiss coin dealer. The unique coin baffled the researchers and raised many questions. Romans minted coins in large numbers, meaning that there only being a single known example made its authenticity, and the existence of Silbannacus, uncertain. The British Museum did not doubt the coin as being genuine, as it resembled other coins of the third century in design and composition, but there were questions as to whether Silbannacus was a real figure. Further evidence taken to confidently establish the coin as genuine was the fact that the portrait of Silbannacus did not completely match that of any other emperor, that there was no evidence of retouching on the letters, and that the image on the reverse of the coin was otherwise more or less unknown. The design and the silver content of the coin confidently places it in the middle of the third century, minted at some point between AD 238 and 260. This makes Silbannacus an emperor or usurper during the turbulent Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis, was a period in History of Rome, Roman history during which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressure of repeated Barbarian invasions ...

when the Roman Empire was plagued by both internal instability and external threats.

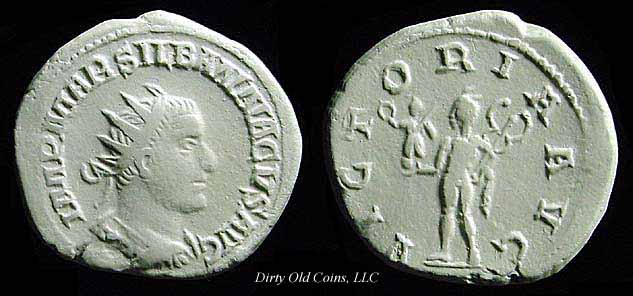

The second coin was held in a private collection for many years after its discovery and its existence was not widely known until it was published by the French historian Sylviane Estiot in 1996. It was only with Estiot's paper that Silbannacus became widely accepted as a real historical figure, his existence now supported by two coins, rather than a single one. Though the coins share the same inscription on the obverse side, they differ on the reverse side. The first coin contains the inscription VICTORIA AVG. and the second coin contains MARTI PROPVGT ("To Mars the defender"). As the only evidence for his existence is two coins, the reign or usurpation of Silbannacus might have been very brief, perhaps lasting just a few weeks, or perhaps just a few days. Considering the period and his obscurity, it is likely that his reign, or usurpation, ended in Silbannacus' death.

Based on the depiction on his coins, Silbannacus was relatively young, had a small head and slightly elongated face, with a slightly aquiline nose. In contrast to the many fully-bearded contemporary emperors, Silbannacus apparently did not have a full beard, but whiskers descending alongside the jawbone, and a beardless chin.

As usurper in Gaul

It is not clear from the coins alone when Silbannacus would have been active. In 1940, the British

It is not clear from the coins alone when Silbannacus would have been active. In 1940, the British numismatist

A numismatist is a specialist, researcher, and/or well-informed collector of numismatics, numismatics/coins ("of coins"; from Late Latin , genitive of ). Numismatists can include collectors, specialist dealers, and scholar-researchers who use coi ...

Harold Mattingly dated the 1937 coin, based on its style, to 249/250. Most later authors have agreed with this approximate mid-3rd century date, and he is most often placed as a usurper in the turbulent reign of Philip the Arab. Craven suggests 248 as the most likely year, placing a revolt by Silbannacus shortly prior to the uprisings of the subsequent usurpers Sponsian, Pacatian and Jotapian. Though it is the most common suggestion, the coin being from the time of Philip is an educated guess, and far from certain. Some historians place Silbannacus in the reign of Philip's successor Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Trajanus Decius ( 201June 251), known as Trajan Decius or simply Decius (), was Roman emperor from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was proclaimed emperor by his troops a ...

(249–251) instead, and others place him as directly preceding Postumus (260–269), who founded the breakaway Gallic Empire, an idea first proposed by the French historian J. M. Doyen in 1989.

In addition to the location of discovery of the coins, another point that might also connect Silbannacus to Gaul is the reverse side of the 1937 coin depicting Mercury holding a Victoria; Mercury being a pre-eminent god in Gaul who would later be used on the coins of Postumus. The inclusion of Mercury is one of the features that makes dating the coin precisely difficult, the deity only being found infrequently on coins before the late third century.

In a 1982 study on usurpers in the third century, Hartmann offered a speculative reconstruction of a revolt by Silbannacus, writing that he might have revolted against Philip in Germania Superior, near the Rhine frontier. Hartmann speculates that Silbannacus might have commanded Germanic auxiliaries in the Roman army. The speculative revolt may have lasted until the beginning of Decius, who is mentioned by the 4th-century historian Eutropius as suppressing an uprising in Gaul. It is possible that Eutropius actually refers to an uprising in Galatia (in Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

), and that reading it as "Gaul" is an error.

In 2019, Craven offered a speculative reconstruction similar to that of Hartmann, writing that Silbannacus might have begun as governor of either Germania Superior

Germania Superior ("Upper Germania") was an imperial province of the Roman Empire. It comprised an area of today's western Switzerland, the French Jura and Alsace regions, and southwestern Germany. Important cities were Besançon ('' Vesont ...

or Germania Inferior

''Germania Inferior'' ("Lower Germania") was a Roman province from AD 85 until the province was renamed ''Germania Secunda'' in the 4th century AD, on the west bank of the Rhine bordering the North Sea. The capital of the province was Colonia Cl ...

, elevated by his troops to emperor after dealing with some forgotten crisis on the Rhine frontier. As the 1937 coin depicts Victoria, and the 1996 coin depicts Mars, deities associated with success in battle, Craven speculated that Silbannacus might have inflicted some surprise defeat on a Germanic invasion. These reconstructions are highly speculative: there are no known records of Germanic tribes threatening the Rhine frontier during the reign of Philip, and the ideas that Silbannacus was a commander or governor are as of yet baseless.

As emperor in Rome

The style of the second coin of Silbannacus appears to copy the design used on the coins of the emperor Aemilian (253), which suggests that Silbannacus ruled later than the time of Philip, possibly around the time of Aemilian's short reign. In particular, both the bust of Silbannacus on the coin, as well as the legend MARTI PROPVGT appears very similar to Aemilian's coins. The similarity might suggest that the coins were made in the same mint, which would mean that Silbannacus held brief control of the mint in the imperial capital.

253 was a turbulent year and many of the events that took place are obscure due to a lack of surviving sources. Aemilian's predecessor was

The style of the second coin of Silbannacus appears to copy the design used on the coins of the emperor Aemilian (253), which suggests that Silbannacus ruled later than the time of Philip, possibly around the time of Aemilian's short reign. In particular, both the bust of Silbannacus on the coin, as well as the legend MARTI PROPVGT appears very similar to Aemilian's coins. The similarity might suggest that the coins were made in the same mint, which would mean that Silbannacus held brief control of the mint in the imperial capital.

253 was a turbulent year and many of the events that took place are obscure due to a lack of surviving sources. Aemilian's predecessor was Trebonianus Gallus

Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus ( 206 – August 253) was Roman emperor from June 251 to August 253, in a joint rule with his son Volusianus.

Early life

Gallus was born in Italy, in a respected senatorial family with Etruscan ancestry, cer ...

(251–253) and Aemilian had been proclaimed emperor by his troops after winning a victory against the Goths

The Goths were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe. They were first reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 3rd century AD, living north of the Danube in what is ...

by the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

. Gallus ordered the general Valerian to defeat the usurper, but Aemilian quickly reached Italy and overthrew Gallus. Aemilian's reign would be cut short when Valerian rebelled against him within weeks. Aemilian departed Rome to battle Valerian but was assassinated by his soldiers before a battle could take place. As features of the second coin are similar to features of coins minted at Rome, it is possible that Silbannacus was not an usurper in Gaul, but a briefly reigning ruler of the Roman capital.

Per the British historian Kevin Butcher, one possibility is that Silbannacus was an officer of Aemilian, who in the aftermath of Aemilian's death secured Rome and tried to rally against Valerian. If this is true, Silbannacus would have been unsuccessful, as Valerian took control of Rome shortly after Aemilian's death. That the coins of Silbannacus have both been found in Gaul does not discredit the idea that he ruled in Rome: currency moved around in the empire and there exists a traceable line of movement of coins from the capital to the Rhine frontier. Before the suggestion that the first coin was minted in Gaul was made, Mattingly had initially written that it was similar to the coins produced for Philip the Arab at Rome. If he ruled the capital, which would require support from the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

, Silbannacus may be counted as a legitimate, albeit ephemeral, emperor, rather than a failed usurper. Silbannacus as a ruler in Rome is supported as the most likely option by some historians, such as Estiot, who published the second coin, and the German historian Udo Hartmann.

See also

* Jotapian * Pacatian * SponsianusReferences

Bibliography

* * * *Web sources

* * ''DIR'' – , Meckler, M. L.; Körner, C.Philip the Arab and Rival Claimants of the later 240s

. Retrieved 2021-04-11. * * {{Roman Emperors 3rd-century deaths 3rd-century Roman usurpers 3rd-century Roman emperors Year of birth unknown Year of death unknown Ancient Romans from unknown gentes Crisis of the Third Century