Shankar Dayal Sharma on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

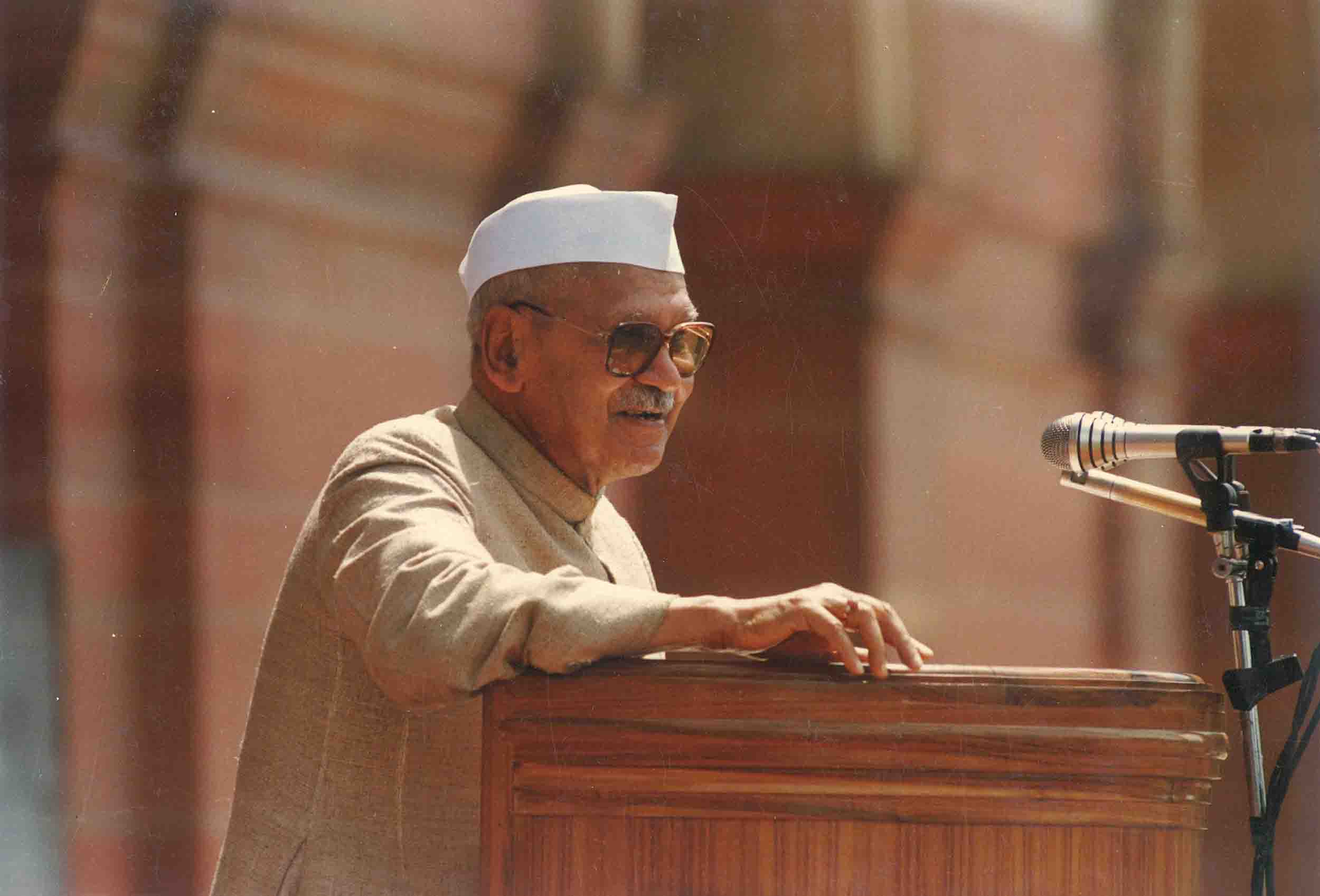

Shankar Dayal Sharma (; 19 August 1918 – 26 December 1999) was an Indian

In June 1992, Sharma was chosen by the Congress party as its candidate for the presidential election of 1992 to succeed R. Venkataraman. His nomination was also supported by the communist parties. The election was held on 13 July 1992 and votes counted three days later. Sharma won 675,804 votes against the 346,485 votes polled by his main opponent George Gilbert Swell, who was the nominee of the opposition

In June 1992, Sharma was chosen by the Congress party as its candidate for the presidential election of 1992 to succeed R. Venkataraman. His nomination was also supported by the communist parties. The election was held on 13 July 1992 and votes counted three days later. Sharma won 675,804 votes against the 346,485 votes polled by his main opponent George Gilbert Swell, who was the nominee of the opposition

On 6 December 1992, the

On 6 December 1992, the

''Dr. Shankar Dayal Sharma'', a 1999 short documentary feature by A. K. Goorha covers his life and presidency. It was produced by the

''Dr. Shankar Dayal Sharma'', a 1999 short documentary feature by A. K. Goorha covers his life and presidency. It was produced by the

Shankar Dayal Sharma

at ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Shankar Dayal Sharma 1918 births 1999 deaths University of Allahabad alumni University of Lucknow alumni Alumni of the University of Cambridge Alumni of the University of London Alumni of the Inns of Court School of Law Harvard Law School alumni Governors of Andhra Pradesh Governors of Maharashtra Governors of Punjab, India Politicians from Lucknow Politicians from Bhopal Presidents of India Presidents of the Indian National Congress Vice presidents of India India MPs 1971–1977 India MPs 1980–1984 Lok Sabha members from Madhya Pradesh Chief ministers from Indian National Congress Indian National Congress politicians from Madhya Pradesh People from Bhopal State Shankar Dayal Sharma

lawyer

A lawyer is a person who is qualified to offer advice about the law, draft legal documents, or represent individuals in legal matters.

The exact nature of a lawyer's work varies depending on the legal jurisdiction and the legal system, as w ...

and politician who served as the President of India

The president of India (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the head of state of the Republic of India. The president is the nominal head of the executive, the first citizen of the country, and the commander-in-chief, supreme commander of the Indian Armed ...

from 1992 to 1997.

Born in Bhopal

Bhopal (; ISO 15919, ISO: Bhōpāl, ) is the capital (political), capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes,'' due to ...

, Sharma studied at Agra

Agra ( ) is a city on the banks of the Yamuna river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, about south-east of the national capital Delhi and 330 km west of the state capital Lucknow. With a population of roughly 1.6 million, Agra is the ...

, Allahabad

Prayagraj (, ; ISO 15919, ISO: ), formerly and colloquially known as Allahabad, is a metropolis in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.The other five cities were: Agra, Kanpur, Kanpur (Cawnpore), Lucknow, Meerut, and Varanasi, Varanasi (Benar ...

and Lucknow

Lucknow () is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and the largest city of the List of state and union territory capitals in India, Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and it is the administrative headquarters of the epon ...

and received a doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''doctor'', meaning "teacher") or doctoral degree is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism '' licentia docendi'' ("licence to teach ...

in constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in ...

from the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

and was a bar-at-law from Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

and a Brandeis Fellow at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

. During 1948–49, Sharma was one of the leaders of the movement for the merger of Bhopal State

Bhopal State (pronounced ) was founded by the Maharaja of Parmar Rajputs. In the beginning of the 18th-century, Bhopal State was converted into an Islamic principality, in the invasion of the Afghan Mughal noble Dost Muhammad Khan. It was ...

with India, a cause for which he served eight months' imprisonment

Imprisonment or incarceration is the restraint of a person's liberty for any cause whatsoever, whether by authority of the government, or by a person acting without such authority. In the latter case it is considered " false imprisonment". Impri ...

.

A member of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

party, Sharma was chief minister

A chief minister is an elected or appointed head of government of – in most instances – a sub-national entity, for instance an administrative subdivision or federal constituent entity. Examples include a state (and sometimes a union ter ...

(1952–56) of Bhopal State

Bhopal State (pronounced ) was founded by the Maharaja of Parmar Rajputs. In the beginning of the 18th-century, Bhopal State was converted into an Islamic principality, in the invasion of the Afghan Mughal noble Dost Muhammad Khan. It was ...

and served as a cabinet minister (1956–1971) in the government of Madhya Pradesh holding several portfolios. Sharma was president of the Bhopal State Congress Committee (1950–52), Madhya Pradesh Congress Committee (1966–68) and of the All India Congress Committee

The All India Congress Committee (AICC) is the presidium or the central decision-making assembly of the Indian National Congress. It is composed of members elected from States and union territories of India, state-level Pradesh Congress Commit ...

(1972–74). He served as Union Minister for Communications (1974–77) under prime minister Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

. Twice elected to the Lok Sabha

The Lok Sabha, also known as the House of the People, is the lower house of Parliament of India which is Bicameralism, bicameral, where the upper house is Rajya Sabha. Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha, Members of the Lok Sabha are elected by a ...

, Sharma served as governor of Andhra Pradesh (1984–85), Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

(1985–86) and Maharashtra

Maharashtra () is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. It is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, the Indian states of Karnataka and Goa to the south, Telangana to th ...

(1986–87) before being elected unopposed as the vice president of India

The vice president of India (ISO: ) is the deputy to the head of state of the Republic of India, i.e. the president of India. The office of vice president is the second-highest constitutional office after the president and ranks second in t ...

in 1987.

Sharma was elected president of India in 1992 and served till 1997 during which period he dealt with four prime ministers

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but rat ...

, three of whom he appointed in the last year of his presidency. He was assertive with the P. V. Narasimha Rao ministry, forcing his government to sack a governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

, instigating a strong response to the demolition of the Babri Masjid

The Babri Masjid, a 16th-century mosque in the Indian city of Ayodhya, was destroyed on 6 December 1992 by a large group of activists of the Vishva Hindu Parishad and allied organisations. The mosque had been the subject of a lengthy socio ...

and refusing to sign ordinances presented to him on the eve of elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

. His appointment of Atal Bihari Vajpayee

Atal Bihari Vajpayee (25 December 1924 – 16 August 2018) was an Indian poet, writer and statesman who served as the prime minister of India, first for a term of 13 days in 1996, then for a period of 13 months from 1998 ...

as prime minister on the grounds of him being the leader of the largest party in the Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

attracted widespread criticism especially as Vajpayee was forced to resign in only thirteen days without facing a vote of confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fit ...

. Sharma's appointment of H. D. Deve Gowda and I. K. Gujral as prime ministers followed the assurance of support to their candidature by the Congress party but neither government lasted more than a year. Sharma chose not to seek a second term in office and was succeeded to the presidency by K. R. Narayanan

Kocheril Raman "K. R." Narayanan (27 October 1920 – 9 November 2005) was an Indian statesman, diplomat, academic, and politician who served as the vice president of India from 1992 to 1997 and president of India from 1997 to 2002.

Naray ...

.

Sharma died in 1999 and was accorded a state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements o ...

. His samadhi

Statue of a meditating Rishikesh.html" ;"title="Shiva, Rishikesh">Shiva, Rishikesh

''Samādhi'' (Pali and ), in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, is a state of meditative consciousness. In many Indian religious traditions, the cultivati ...

lies at Karma Bhumi in Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, but spread chiefly to the west, or beyond its Bank (geography ...

.

Early life and education

Shankar Dayal Sharma was born on 19 August 1918 inBhopal

Bhopal (; ISO 15919, ISO: Bhōpāl, ) is the capital (political), capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes,'' due to ...

, then the capital of the princely state of Bhopal

Bhopal (; ISO 15919, ISO: Bhōpāl, ) is the capital (political), capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes,'' due to ...

, in a Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

Gaur Brahmin family. Sharma completed his schooling in Bhopal and then studied at St. John's College, Agra and at the Allahabad

Prayagraj (, ; ISO 15919, ISO: ), formerly and colloquially known as Allahabad, is a metropolis in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.The other five cities were: Agra, Kanpur, Kanpur (Cawnpore), Lucknow, Meerut, and Varanasi, Varanasi (Benar ...

and Lucknow

Lucknow () is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and the largest city of the List of state and union territory capitals in India, Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and it is the administrative headquarters of the epon ...

universities obtaining a MA in English, Hindi

Modern Standard Hindi (, ), commonly referred to as Hindi, is the Standard language, standardised variety of the Hindustani language written in the Devanagari script. It is an official language of India, official language of the Government ...

and Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

and an L.L.M. He topped both the courses, was awarded the Chakravarty Gold Medal for social service, and was a thrice swimming champion at Lucknow University and cross country running

Cross country running is a sport in which teams and individuals run a race on open-air courses over natural terrain such as dirt or grass. The course, typically long, may include surfaces of grass and soil, earth, pass through woodlands and ope ...

champion at Allahabad

Prayagraj (, ; ISO 15919, ISO: ), formerly and colloquially known as Allahabad, is a metropolis in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.The other five cities were: Agra, Kanpur, Kanpur (Cawnpore), Lucknow, Meerut, and Varanasi, Varanasi (Benar ...

.

He obtained a doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''doctor'', meaning "teacher") or doctoral degree is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism '' licentia docendi'' ("licence to teach ...

in constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in ...

from University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

for his thesis on ''Interpretation of Legislative Powers under Federal Constitutions'' and received a diploma

A diploma is a document awarded by an educational institution (such as a college or university) testifying the recipient has graduated by successfully completing their courses of studies. Historically, it has also referred to a charter or offi ...

in public administration

Public administration, or public policy and administration refers to "the management of public programs", or the "translation of politics into the reality that citizens see every day",Kettl, Donald and James Fessler. 2009. ''The Politics of the ...

from the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a collegiate university, federal Public university, public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The ...

.

Sharma began practicing law at Lucknow

Lucknow () is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and the largest city of the List of state and union territory capitals in India, Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and it is the administrative headquarters of the epon ...

from 1940 where he taught law at the university and soon joined the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

. In 1946, he was admitted to the Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

and taught at Cambridge University during 1946–47. The following year, he was appointed a Brandeis Fellow at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

.

Political career in Madhya Pradesh

During 1948–49, Sharma underwent eight months' imprisonment for his leadership of the popular movement for merging the princely state of Bhopal with India. Although theNawab of Bhopal

The Nawabs of Bhopal were the Muslim rulers of Bhopal, now part of Madhya Pradesh, India. The nawabs first ruled under the Mughal Empire from 1707 to 1737, under the Maratha Confederacy from 1737 to 1818, then under British rule from 1818 to 19 ...

had acceded his state to the Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,

*

* was an independent dominion in the British Commonwealth of Nations existing between 15 August 1947 and 26 January 1950. Until its Indian independence movement, independence, India had be ...

, he had held out against signing the Instrument of Accession

The Instrument of Accession was a legal document first introduced by the Government of India Act 1935 and used in 1947 to enable each of the rulers of the princely states under British paramountcy to join one of the new dominions of Dominion ...

. The popular movement had the support of the Praja Mandal and an interim government with Chatur Narain Malviya as its head was constituted by the Nawab in 1948. However, as the movement gained support, the Nawab dismissed this government. Public pressure and the intervention of V. P. Menon led the Nawab to merge his state with the Indian Union in 1949 with the princely state reconstituted as Bhopal State

Bhopal State (pronounced ) was founded by the Maharaja of Parmar Rajputs. In the beginning of the 18th-century, Bhopal State was converted into an Islamic principality, in the invasion of the Afghan Mughal noble Dost Muhammad Khan. It was ...

.

Sharma was president of the Bhopal State Congress during 1950 to 1952. He was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Bhopal from Berasia

Berasia is a town and a nagar palika (municipality) in Bhopal district in the state of Madhya Pradesh, India.

History

In the early 18th century, Berasia was a small ''mustajiri'' (rented estate) under the authority of the Delhi-based Mug ...

in the elections of 1952 and became chief minister

A chief minister is an elected or appointed head of government of – in most instances – a sub-national entity, for instance an administrative subdivision or federal constituent entity. Examples include a state (and sometimes a union ter ...

of Bhopal State in 1952. In 1956, following the reorganization of states, Bhopal State was merged with the new state of Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (; ; ) is a state in central India. Its capital is Bhopal and the largest city is Indore, Indore. Other major cities includes Gwalior, Jabalpur, and Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, Sagar. Madhya Pradesh is the List of states and union te ...

. Sharma played an important role in retaining Bhopal as the capital of this new state. In the elections of 1957

Events January

* January 1 – The Saarland joins West Germany.

* January 3 – Hamilton Watch Company introduces the first electric watch.

* January 5 – South African player Russell Endean becomes the first batsman to be Dismissal (cricke ...

, 1962

The year saw the Cuban Missile Crisis, which is often considered the closest the world came to a Nuclear warfare, nuclear confrontation during the Cold War.

Events January

* January 1 – Samoa, Western Samoa becomes independent from Ne ...

and 1967

Events January

* January 1 – Canada begins a year-long celebration of the 100th anniversary of Canadian Confederation, Confederation, featuring the Expo 67 World's Fair.

* January 6 – Vietnam War: United States Marine Corps and Army of ...

, Sharma was elected to the Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly

The Madhya Pradesh Vidhan Sabha or the Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly is the unicameral state legislature of Madhya Pradesh state in India.

The seat of the Vidhan Sabha is at Bhopal, the capital of the state. It is housed in the ''Vidh ...

from Udaipura as a candidate of the Congress party. During this time he was a cabinet minister

A minister is a politician who heads a ministry, making and implementing decisions on policies in conjunction with the other ministers. In some jurisdictions the head of government is also a minister and is designated the ' prime minister', ' p ...

in the Madhya Pradesh government and variously held portfolios of education, law, public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and procured by a government body for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, ...

, industry and commerce and revenue. As minister for education, he emphasized secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

pedagogy

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken ...

in schools and textbooks were revised to avoid religious bias.

During 1967–68, he was president of the Madhya Pradesh Congress Committee and served as general secretary of the party from 1968 to 1972. During the split in 1969, Sharma sided with Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

and was removed from party posts by the president S. Nijalingappa but reappointed by Gandhi in her faction of the party.

Parliamentary career

Sharma was elected to the Lok Sabha fromBhopal

Bhopal (; ISO 15919, ISO: Bhōpāl, ) is the capital (political), capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes,'' due to ...

in the general elections of 1971. The following year, he was made the president of the Indian National Congress

The national president of the Indian National Congress is the chief executive of the Indian National Congress (INC), one of the principal political parties in India. Constitutionally, the president is elected by an electoral college composed of ...

by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

. Prior to his appointment as president, Sharma had been a member of the Congress Working Committee

The Congress Working Committee (CWC) is the executive committee of the Indian National Congress. It was formed in December 1920 at Nagpur session of INC which was headed by C. Vijayaraghavachariar. It is composed of senior party leaders and is r ...

since 1967 and general secretary of the Congress party from 1968. As president, Sharma launched a public campaign against the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

accusing it of being actively involved in fomenting violence in India.

In October 1974, Sharma was appointed Minister of Communications in the Indira Gandhi ministry and was succeeded as president of the Congress by D. K. Barooah. He remained in that post until his defeat in the general election of 1977 by Arif Baig. Sharma was reelected from Bhopal in the general election of 1980.

Gubernatorial tenures (1984–1987)

Governor of Andhra Pradesh (1984–1985)

On 15 August 1984, N. T. Rama Rao, thechief minister of Andhra Pradesh

The chief minister of Andhra Pradesh is the chief executive of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. In accordance with the Constitution of India, the governor is a state's ''de jure'' head, but '' de facto'' executive authority rests with the ch ...

who led the Telugu Desam Party

The Telugu Desam Party (TDP; ) is an Indian regional political party primarily active in the Federated state, states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. It was founded by Telugu cinema, Telugu matinée idol N. T. Rama Rao (NTR) on 29 March 1982 a ...

(TDP) to victory in the state assembly election of 1983, was dismissed from that post by the governor of Andhra Pradesh, Thakur Ram Lal. He appointed N. Bhaskara Rao, who had been the finance minister

A ministry of finance is a ministry or other government agency in charge of government finance, fiscal policy, and financial regulation. It is headed by a finance minister, an executive or cabinet position .

A ministry of finance's portfoli ...

under Rama Rao, as the new chief minister and gave him a month's time to prove his majority in the Assembly despite the ousted chief minister's claim of being able to prove his own majority in two days' time and evidence that he had the support of the majority of legislators in the assembly. Following widespread protests, Ram Lal resigned on 24 August 1984 and was replaced by Sharma.

Sharma convened a session of the Assembly on 11 September 1984 but as Bhaskara Rao failed to prove his majority within the period of one month stipulated by Ram Lal, Sharma suggested that he resign with effect from 16 September. Bhaskar Rao refused to do so seeking the reconvening of the Assembly a few days later. Sharma then dismissed him and reappointed Rama Rao as chief minister. Rama Rao won the vote of confidence when the Assembly reconvened on 20 September 1984. Soon after, the Rama Rao government called for fresh elections and Sharma dissolved the Assembly in November 1984.

In the Assembly election of 1985, TDP was returned to power with a two-thirds majority with Rama Rao returning as the chief minister. A few months later, Sharma refused to repromulgate three ordinances sent to him by the Rama Rao's government stating that ordinances are required to be ratified by the legislature and that their repromulgation would be a constitutional impropriety. His refusal to repromulgate these ordinances, pertaining to the abolition of offices of part-time village officers, formation of districts and payment of salaries and removal of disqualifications of government employees, a fourth time soured his relation with the state government.

On 31 July 1985, Sharma's daughter Gitanjali and his son-in-law, the Congress politician Lalit Maken, were killed by Sikh militants in retaliation for Maken's alleged role in the anti-Sikh riots of 1984. Lalit Maken was among the most promising young parliamentarian. Outspoken and a firebrand trade unionist, he will be remembered for his valiant struggle for the downtrodden. Sharma was thereafter transferred to Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

as governor and was succeeded in Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh (ISO 15919, ISO: , , AP) is a States and union territories of India, state on the East Coast of India, east coast of southern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, seventh-largest state and th ...

by Kumudben Joshi.

Governor of Punjab (1985–1986)

Sharma succeeded Hokishe Sema as governor of Punjab in November 1985. His appointment came after the assembly elections in that state and in the backdrop of the Rajiv–Longowal Accord which sought to resolve the insurgency in Punjab.Governor of Maharashtra (1986–1987)

Sharma was sworn in asgovernor of Maharashtra

The governor of Maharashtra is the ceremonial head of the Indian state of Maharashtra. The Constitution of India confers the executive powers of the state to the governor; however, the de facto executive powers lie with the Council of Minister ...

in April 1986 and served until September 1987 when he was elected vice president of India

The vice president of India (ISO: ) is the deputy to the head of state of the Republic of India, i.e. the president of India. The office of vice president is the second-highest constitutional office after the president and ranks second in t ...

.

Vice President of India (1987–1992)

Sharma was nominated by the Congress party for the vice-presidential election of 1987. Although 27 candidates had filed nominations, only the nomination filed by Sharma was found valid by the returning officer. After the last date of withdrawal of candidates was over, Sharma was declared elected unanimously on 21 August 1987. Sharma was sworn in as thevice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

on 3 September 1987. He was only the third person to be elected unopposed to the vice-presidency.

Sharma, who was also the ex-officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, or council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term ''List of Latin phrases (E)#ex officio, ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the off ...

chairman of the Rajya Sabha

Rajya Sabha (Council of States) is the upper house of the Parliament of India and functions as the institutional representation of India’s federal units — the states and union territories.https://rajyasabha.nic.in/ It is a key component o ...

, offered to quit in February 1988 after his ruling admitting a discussion in the house of the purported extravagance of the then governor of Andhra Pradesh was vociferously objected to by members of the government. Several ministers of the council of ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

led the protests against Sharma's ruling even as Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi

Rajiv Gandhi (20 August 1944 – 21 May 1991) was an Indian statesman and pilot who served as the prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989. He took office after the Assassination of Indira Gandhi, assassination of his mother, then–prime ...

, who was present in the house, chose not to intervene or restrain the members of his party. Sharma's response chastened the protesting members but their request to have the proceedings expunged from Parliament records was turned down by Sharma.

In 1991, following the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi

The assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, former prime minister of India, occurred as a result of a suicide bombing in Sriperumbudur in Tamil Nadu, India on 21 May 1991. At least 14 others, in addition to Gandhi and the assassin, were killed. It w ...

, Sharma was first offered the presidentship of the Congress party and the post of prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

by Sonia Gandhi

Sonia Gandhi (, ; ; born 9 December 1946) is an Indian politician. She is the longest-serving president of the Indian National Congress, a big-tent liberal political party, which has governed India for most of its post-independence history. ...

. He however refused citing ill health and advanced age. Thereafter, P. V. Narasimha Rao

Pamulaparthi Venkata Narasimha Rao (28 June 1921 – 23 December 2004) was an Indian independence activist, lawyer, and statesman from the Indian National Congress who served as the prime minister of India from 1991 to 1996. He was the first p ...

was chosen to lead the Congress party.

President of India (1992–1997)

In June 1992, Sharma was chosen by the Congress party as its candidate for the presidential election of 1992 to succeed R. Venkataraman. His nomination was also supported by the communist parties. The election was held on 13 July 1992 and votes counted three days later. Sharma won 675,804 votes against the 346,485 votes polled by his main opponent George Gilbert Swell, who was the nominee of the opposition

In June 1992, Sharma was chosen by the Congress party as its candidate for the presidential election of 1992 to succeed R. Venkataraman. His nomination was also supported by the communist parties. The election was held on 13 July 1992 and votes counted three days later. Sharma won 675,804 votes against the 346,485 votes polled by his main opponent George Gilbert Swell, who was the nominee of the opposition Bharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; , ) is a political party in India and one of the two major List of political parties in India, Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. BJP emerged out from Syama Prasad Mukherjee's ...

. Two other candidates – Ram Jethmalani

Ram Boolchand Jethmalani (14 September 1923 – 8 September 2019) was an Indian lawyer and politician. He served as India's Union Minister of Law and Justice, as chairman of the Indian Bar Council, and as the president of the Supreme Court B ...

and Kaka Joginder Singh – won a small number of votes. Sharma was declared elected on 16 July 1992 and was sworn in as president on 25 July 1992. In his inaugural address, Sharma stated that "Freedom

Freedom is the power or right to speak, act, and change as one wants without hindrance or restraint. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving oneself one's own laws".

In one definition, something is "free" i ...

has little meaning without equality

Equality generally refers to the fact of being equal, of having the same value.

In specific contexts, equality may refer to:

Society

* Egalitarianism, a trend of thought that favors equality for all people

** Political egalitarianism, in which ...

and equality has little meaning without social justice

Social justice is justice in relation to the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society where individuals' rights are recognized and protected. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has of ...

" and committed himself to combating terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

, poverty

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse Biophysical environmen ...

, disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

and communalism in India. The validity of the election was challenged unsuccessfully before the Supreme Court of India

The Supreme Court of India is the supreme judiciary of India, judicial authority and the supreme court, highest court of the Republic of India. It is the final Appellate court, court of appeal for all civil and criminal cases in India. It also ...

.

Narasimha Rao government (1992–1996)

Sharma's victory was seen as a victory for the Congress party and Prime MinisterP. V. Narasimha Rao

Pamulaparthi Venkata Narasimha Rao (28 June 1921 – 23 December 2004) was an Indian independence activist, lawyer, and statesman from the Indian National Congress who served as the prime minister of India from 1991 to 1996. He was the first p ...

who headed a minority government

A minority government, minority cabinet, minority administration, or a minority parliament is a government and cabinet formed in a parliamentary system when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in ...

. Although seen as a largely ceremonial post, the office of the president is key since the incumbent gets to nominate a head of government in the event of no party gaining a majority in Parliament after national elections or after a government had lost a vote of confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fit ...

. The Rao ministry faced three no-confidence motions during its tenure the third of which, held in July 1993, was marred by allegations of bribery

Bribery is the corrupt solicitation, payment, or Offer and acceptance, acceptance of a private favor (a bribe) in exchange for official action. The purpose of a bribe is to influence the actions of the recipient, a person in charge of an official ...

and subsequent criminal indictment against Rao himself. On 6 December 1992, the

On 6 December 1992, the Babri Masjid

The Babri Masjid (ISO: Bābarī Masjida; meaning ''Mosque of Babur'') was a mosque located in Ayodhya, in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. It was claimed that the mosque was built upon the site of Ram Janmabhoomi, the legendary birthplace ...

in Ayodhya

Ayodhya () is a city situated on the banks of the Sarayu river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is the administrative headquarters of the Ayodhya district as well as the Ayodhya division of Uttar Pradesh, India. Ayodhya became th ...

was demolished

Demolition (also known as razing and wrecking) is the science and engineering in safely and efficiently tearing down buildings and other artificial structures. Demolition contrasts with deconstruction, which involves taking a building apa ...

by a fanatic Hindu mob which led to widespread rioting across India. Sharma expressed his deep anguish and pain at the demolition and condemned the action as being contrary to the traditional ethos of India of respecting all religions and as opposed to the precepts of Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for a range of Indian religions, Indian List of religions and spiritual traditions#Indian religions, religious and spiritual traditions (Sampradaya, ''sampradaya''s) that are unified ...

. Sharma's strong condemnation of the incident forced the Rao government to dismiss the state government

A state government is the government that controls a subdivision of a country in a federal form of government, which shares political power with the federal or national government. A state government may have some level of political autonom ...

and impose President's rule in Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh ( ; UP) is a States and union territories of India, state in North India, northern India. With over 241 million inhabitants, it is the List of states and union territories of India by population, most populated state in In ...

, the state in which Ayodhya is located, the same evening. The following day, the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO 15919, ISO: Bhārata Sarakāra, legally the Union Government or Union of India or the Central Government) is the national authority of the Republic of India, located in South Asia, consisting of States and union t ...

, by way of a presidential ordinance, acquired of land in and around the spot where the mosque had stood and provided that all litigation relating to the disputed area would stand dissolved following the acquisition. In January 1993, a reference was made by Sharma to India's Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

as to whether a Hindu temple

A Hindu temple, also known as Mandir, Devasthanam, Pura, or Kovil, is a sacred place where Hindus worship and show their devotion to Hindu deities, deities through worship, sacrifice, and prayers. It is considered the house of the god to who ...

or religious structure had existed prior to the construction of the Babri Masjid at the disputed area where the mosque stood. In 1994, by a majority decision, the Court refused to answer the reference as it held it to be contrary to the spirit of secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on naturalistic considerations, uninvolved with religion. It is most commonly thought of as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state and may be broadened ...

and likely to favour a religious community.

In 1995, Sharma dedicated to the Indian people

Indian people or Indians are the Indian nationality law, citizens and nationals of the India, Republic of India or people who trace their ancestry to India. While the demonym "Indian" applies to people originating from the present-day India, ...

the reconstructed Somnath temple in Gujarat

Gujarat () is a States of India, state along the Western India, western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the List of states and union territories ...

. At the dedication ceremony, Sharma stated that all religions taught the same lesson of unity and placed humanism above all else. The construction of the temple had lasted for fifty years. Questions about its financing, the role of the state in its reconstruction and the presence of constitutional functionaries during the installation of the idol had been marked by debates on secularism in the years following India's independence

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic movement t ...

. The same year, even as the Narasimha Rao government dithered on acting against Sheila Kaul, the governor of Himachal Pradesh

The governor of Himachal Pradesh (ISO: Himachal Pradēśa kē Rājyapāla) is the constitutional head of the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. Shiv Pratap Shukla is the 22nd governor (31st if governors with additional charge also counted) of H ...

, after the Supreme Court expressed its concern that she was using her gubernatorial immunity to avoid criminal proceedings, Sharma forced the government to get her to resign immediately.

Sharma largely enjoyed cordial ties with Narasimha Rao government. In 1996, however, two ordinances sent to him by the Rao government seeking to extend the benefits of reservations in state employment and education for Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

and Muslim Dalits and to reduce the time allowed for campaigning in elections, were returned by Sharma on the grounds that elections were imminent and therefore such decisions should be left to the incoming government.

Vajpayee government (16 May 1996 – 28 May 1996)

In the general elections of 1996, no party got a majority in Parliament but theBharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; , ) is a political party in India and one of the two major List of political parties in India, Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. BJP emerged out from Syama Prasad Mukherjee's ...

emerged the largest party winning 160 seats out of 543. The ruling Congress party came second with 139 seats. On 15 May 1996, Sharma invited Atal Bihari Vajpayee, as the leader of the single largest party, to be the prime minister on the condition that he prove his majority on the floor of the house before 31 May. Vajpayee and a cabinet of 11 ministers were sworn in the following day. President Sharma addressed the new parliament on 24 May. The motion for vote of confidence was taken up and discussed on 27 and 28 May. However, before the motion could be put to vote, Vajpayee announced his resignation. The government lasted only 13 days, the shortest in India's history.

President Sharma's decision of selecting Vajpayee as prime minister drew criticism from several quarters. Unlike presidents Ramaswamy Venkataraman or Neelam Sanjiva Reddy

Neelam Sanjiva Reddy (19 May 1913 – 1 June 1996) was an Indian politician who served as the president of India, serving from 1977 to 1982. Beginning a long political career with the Indian National Congress Party in the independence movem ...

who had asked prime ministerial candidates to produce lists of their supporting MPs, thus satisfying themselves that the prime ministers appointed would be able to win a vote of confidence, Sharma had made no such demands of Vajpayee and had appointed him solely by the principle of inviting the leader of the largest party in Parliament. Also, unlike President Venkataraman, Sharma issued no press communiqués outlining the rationale for his decision. The Communist parties criticized Sharma's decision as he had been elected president with their backing but had chosen to invite their ideological opponent to be the prime minister.

Sharma's decision to invite Vajpayee has been attributed to the fact that no party had staked their claim to form the government and the United Front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political and/ ...

, a coalition of thirteen parties, took time to decide on their leader and in getting the Congress party to extend its support to them. Sharma's deadline of two weeks given to Vajpayee to prove his majority was much shorter than the time given to prime ministers in previous instances and was a move to discourage horse trading

Horse trading, in its literal sense, is the buying and selling of horses, also called "horse dealing". Due to the difficulties in evaluating the merits of a horse offered for sale, the sale of horses offered great opportunities for dishonesty, l ...

.

Deve Gowda government (1996–1997)

Following Vajpayee's resignation, Sharma asked him to continue as caretaker prime minister and appointed H. D. Deve Gowda as prime minister on 28 May 1996 after being assured of the support of the Congress party for his candidature. Gowda and a 21 membercouncil of ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

sworn in on 1 June and won a vote of confidence within the deadline of twelve days set by Sharma. Gowda, a former chief minister of Karnataka

The Chief minister (India), chief minister of Karnataka is the Head of government, chief executive officer of the Government of Karnataka, government of the Indian state of Karnataka. As per the Constitution of India, the governor of Karnatak ...

, was India's third prime minister in as many weeks and headed a diverse coalition comprising regional parties, leftists and lower caste Hindu politicians. He was also India's first prime minister not conversant in its official language

An official language is defined by the Cambridge English Dictionary as, "the language or one of the languages that is accepted by a country's government, is taught in schools, used in the courts of law, etc." Depending on the decree, establishmen ...

, Hindi

Modern Standard Hindi (, ), commonly referred to as Hindi, is the Standard language, standardised variety of the Hindustani language written in the Devanagari script. It is an official language of India, official language of the Government ...

. The government lasted ten months and was dependent on the Congress party which, under its new president Sitaram Kesri

Sitaram Kesri (15 November 1919 – 24 October 2000) was an Indian politician and parliamentarian. He became a union minister and served as President of the Indian National Congress from 1996 to 1998.

__TOC__

Political career

Pre-Independenc ...

, withdrew support in April 1997 alleging failure on the part of the prime minister in preventing the growth of Hindu nationalist political parties in North India

North India is a geographical region, loosely defined as a cultural region comprising the northern part of India (or historically, the Indian subcontinent) wherein Indo-Aryans (speaking Indo-Aryan languages) form the prominent majority populati ...

. Sharma then directed Gowda to seek a vote of confidence in Parliament. Gowda lost the vote of confidence on 11 April 1997 and continued to head a caretaker government as President Sharma considered a further course of action.

I. K. Gujral government

On 21 April 1997, Inder Kumar Gujral, who had been theforeign minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

under Deve Gowda, was sworn in as prime minister and was given two days time win a vote of confidence in Parliament. He was the third prime minister to be sworn in by Sharma and his government would last 322 days when the Congress party again withdrew support to the United Front ministry.

State visits

As president, Sharma led state visits toBulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

, Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, Namibia

Namibia, officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country on the west coast of Southern Africa. Its borders include the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south; in the no ...

, Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

, Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago, officially the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, is the southernmost island country in the Caribbean, comprising the main islands of Trinidad and Tobago, along with several List of islands of Trinidad and Tobago, smaller i ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, and Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

. At the end of his tenure, he chose not to seek a second term in office and was succeeded to the presidency by Vice President K. R. Narayanan

Kocheril Raman "K. R." Narayanan (27 October 1920 – 9 November 2005) was an Indian statesman, diplomat, academic, and politician who served as the vice president of India from 1992 to 1997 and president of India from 1997 to 2002.

Naray ...

.

Death

Sharma died due to heart attack at the Escorts Heart Institute, Delhi on 26 December 1999. He was married to Vimala and had two sons and a daughter. The Government of India declared seven days of national mourning in his honour. Astate funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements o ...

was accorded to him and he was cremated

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a corpse through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India, Nepal, and ...

on 27 December 1999. His samadhi

Statue of a meditating Rishikesh.html" ;"title="Shiva, Rishikesh">Shiva, Rishikesh

''Samādhi'' (Pali and ), in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, is a state of meditative consciousness. In many Indian religious traditions, the cultivati ...

lies at Karma Bhumi, Delhi.

Honours

Sharma was made an honorary bencher and Master ofLincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

in 1993. He was conferred an honorary degree of doctor of law

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

by the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. He was also conferred with honorary doctorates from the Sofia University

Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridski" () is a public university, public research university in Sofia, Bulgaria. It is the oldest institution of higher education in Bulgaria.

Founded on 1 October 1888, the edifice of the university was constr ...

, University of Bucharest

The University of Bucharest (UB) () is a public university, public research university in Bucharest, Romania. It was founded in its current form on by a decree of Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza to convert the former Princely Academy of Bucharest, P ...

, the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv

The Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (; also known as Kyiv University, Shevchenko University, or KNU) is a public university in Kyiv, Ukraine.

The university is the third-oldest university in Ukraine after the University of Lviv and ...

and several Indian universities.

Bibliography

Sharma was the author of several books in English and Hindi. These include ''The Congress Approach to International Affairs'', ''Studies in Indo-Soviet cooperation'', ''Rule of Law and Role of Police'', ''Jawaharlal Nehru: The Maker of Modern Commonwealth'', ''Eminent Indians'', ''Chetna Ke Strot'' and ''Hindi Bhasha Aur Sanskriti''. He was also editor of the ''Lucknow Law Journal'', ''Socialist India'', ''Jyoti'' and the ''Ilm-o-Nur''.Commemoration

''Dr. Shankar Dayal Sharma'', a 1999 short documentary feature by A. K. Goorha covers his life and presidency. It was produced by the

''Dr. Shankar Dayal Sharma'', a 1999 short documentary feature by A. K. Goorha covers his life and presidency. It was produced by the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO 15919, ISO: Bhārata Sarakāra, legally the Union Government or Union of India or the Central Government) is the national authority of the Republic of India, located in South Asia, consisting of States and union t ...

's Films Division. In 2000, a commemorative postage stamp was issued in his honour by India Post

The Department of Posts, d/b/a India Post, is an Indian Public Sector Undertakings in India, public sector postal system statutory body headquartered in New Delhi, India. It is an organisation under the Ministry of Communications (India), Minist ...

. In Bhopal, the Dr. Shankar Dayal Sharma Ayurvedic College & Hospital and the Dr. Shankar Dayal Sharma College are named after him. Dr. Shankar Dayal Sharma Institute of Democracy under the University of Lucknow was inaugurated in 2009.

The Shankar Dayal Sharma Gold Medal, awarded annually at several universities in India, was instituted in 1994 from endowments made by Sharma.

Notes

References

External links

Shankar Dayal Sharma

at ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Shankar Dayal Sharma 1918 births 1999 deaths University of Allahabad alumni University of Lucknow alumni Alumni of the University of Cambridge Alumni of the University of London Alumni of the Inns of Court School of Law Harvard Law School alumni Governors of Andhra Pradesh Governors of Maharashtra Governors of Punjab, India Politicians from Lucknow Politicians from Bhopal Presidents of India Presidents of the Indian National Congress Vice presidents of India India MPs 1971–1977 India MPs 1980–1984 Lok Sabha members from Madhya Pradesh Chief ministers from Indian National Congress Indian National Congress politicians from Madhya Pradesh People from Bhopal State Shankar Dayal Sharma