Seymouria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Seymouria'' is an

In 1966, Peter Paul Vaughn described an assortment of ''Seymouria'' skulls from the

In 1966, Peter Paul Vaughn described an assortment of ''Seymouria'' skulls from the  A block of sediment containing six ''S. sanjuanensis'' skeletons was found in the

A block of sediment containing six ''S. sanjuanensis'' skeletons was found in the

''Seymouria'' individuals were robustly-built animals, with a large head, short neck, stocky limbs, and broad feet. Even the largest specimens were fairly small, only about 2 ft (60 cm) long. The skull was boxy and roughly triangular when seen from above, but it was lower and longer than that of most other seymouriamorphs. The vertebrae had broad, swollen neural arches (the portion above the spinal cord). As a whole the body shape was similar to that of contemporary reptiles and reptile-like tetrapods such as

''Seymouria'' individuals were robustly-built animals, with a large head, short neck, stocky limbs, and broad feet. Even the largest specimens were fairly small, only about 2 ft (60 cm) long. The skull was boxy and roughly triangular when seen from above, but it was lower and longer than that of most other seymouriamorphs. The vertebrae had broad, swollen neural arches (the portion above the spinal cord). As a whole the body shape was similar to that of contemporary reptiles and reptile-like tetrapods such as

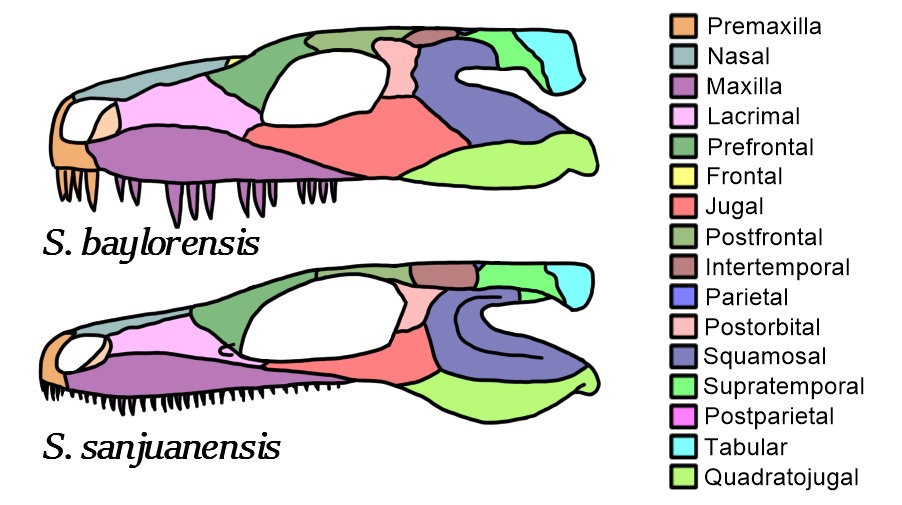

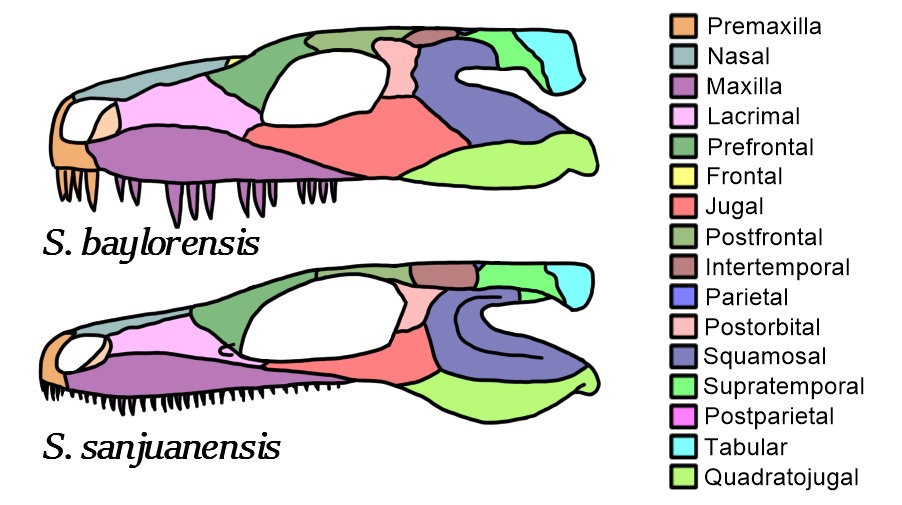

The skull was composed of many smaller plate-like bones. The configuration of skull bones present in ''Seymouria'' was very similar to that of far more ancient tetrapods and tetrapod relatives. For example, it retains an

The skull was composed of many smaller plate-like bones. The configuration of skull bones present in ''Seymouria'' was very similar to that of far more ancient tetrapods and tetrapod relatives. For example, it retains an

The

The

Some authors have argued that the postparietals of ''S. baylorensis'' were smaller than those of ''S. sanjuanensis'', but some specimens of ''S. sanjuanensis'' (for example, the "Tambach lovers") also had small postparietals. In addition, the "Tambach lovers" have a

Some authors have argued that the postparietals of ''S. baylorensis'' were smaller than those of ''S. sanjuanensis'', but some specimens of ''S. sanjuanensis'' (for example, the "Tambach lovers") also had small postparietals. In addition, the "Tambach lovers" have a

A photograph of the "Tambach lovers" specimen, published by Mark MacDougall's twitter accountAnother photograph of the "Tambach lovers", published by "Geology Page"A photograph of the Cutler Formation block, published by "mskvarla36"'s twitter accountTranslated DW documentary on Tambach fossils, including ''Seymouria''

{{Taxonbar, from=Q131455 Seymouriamorpha Cisuralian tetrapods of Europe Cisuralian tetrapods of North America Fossil taxa described in 1904

extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of seymouriamorph from the Early Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

and Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

. Although they were amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s (in a biological sense), ''Seymouria'' were well-adapted to life on land, with many reptilian features—so many, in fact, that ''Seymouria'' was first thought to be a primitive reptile. It is primarily known from two species, ''Seymouria baylorensis'' and ''Seymouria sanjuanensis''. The type species, ''S. baylorensis'', is more robust and specialized, though its fossils have only been found in Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

. On the other hand, ''S. sanjuanensis'' is more abundant and widespread. This smaller species is known from multiple well-preserved fossils, including a block of six skeletons found in the Cutler Formation

The Cutler Formation or Cutler Group is a stratigraphic unit exposed across the U.S. states of Arizona, northwest New Mexico, southeast Utah and southwest Colorado. It was laid down in the Early Permian during the Wolfcampian epoch.

Desc ...

of New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

, and a pair of fully grown skeletons from the Tambach Formation of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, which were fossilized lying next to each other.

For the first half of the 20th century, ''Seymouria'' was considered one of the oldest and most "primitive" known reptiles. Paleontologists noted how the general body shape resembled that of early reptiles such as captorhinids

Captorhinidae is an extinct family of tetrapods, traditionally considered primitive reptiles, known from the late Carboniferous to the Late Permian. They had a cosmopolitan distribution across Pangea.

Description

Captorhinids are a clade of sm ...

, and that certain adaptations of the limbs, hip, and skull were also similar to that of early reptiles, rather than any species of modern or extinct amphibians known at the time. The strongly-built limbs and backbone also supported the idea that ''Seymouria'' was primarily terrestrial, spending very little time in the water. However, in the 1950s, fossilized tadpole

A tadpole or polliwog (also spelled pollywog) is the Larva, larval stage in the biological life cycle of an amphibian. Most tadpoles are fully Aquatic animal, aquatic, though some species of amphibians have tadpoles that are terrestrial animal, ...

s were discovered in '' Discosauriscus'', which was a close relative of ''Seymouria'' in the group Seymouriamorpha

Seymouriamorpha were a small but widespread group of limbed vertebrates (tetrapods). They have long been considered stem group, stem-amniotes (reptiliomorphs), and most paleontologists still accept this point of view, but some analyses suggest th ...

. This shows that seymouriamorphs (including ''Seymouria'') had a larval stage which lived in the water, therefore making ''Seymouria'' not a true reptile, but rather an amphibian (in the traditional, paraphyletic sense of the term). At that time, it was still thought to be closely related to reptiles, and many recent studies still support this hypothesis. If this hypothesis is correct, ''Seymouria'' is still an important transitional fossil

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross ...

documenting the acquisition of reptile-like skeletal features prior to the evolution of the amniotic egg, which characterizes amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s (reptiles, mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, and bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s). However, under the alternative hypothesis that ''Seymouria'' is a stem-tetrapod, it has little relevance to the origin of amniotes.

History

Early history as a putative reptile

Fossils of ''Seymouria'' were first found near the town of Seymour, in Baylor County,Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

(hence the name of the type species, ''Seymouria baylorensis'', referring to both the town and county). The earliest fossils of the species to be collected were a cluster of individuals acquired by C.H. Sternberg in 1882. However, these fossils would not be properly prepared and identified as ''Seymouria'' until 1930.

Various paleontologists from around the world recovered their own ''Seymouria baylorensis'' fossils in the late 19th century and early 20th century. ''Seymouria'' was formally named and described in 1904 based on a pair of incomplete skulls, one of which was associated with a few pectoral and vertebral elements. These fossils were described by German paleontologist Ferdinand Broili, and are now stored in Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

. American paleontologist S.W. Williston later described a nearly complete skeleton in 1911, and noted that "''Desmospondylus anomalus''", a taxon he had recently named from fragmentary limbs and vertebrae, likely represented juvenile or even embryonic individuals of ''Seymouria''.

Likewise, English paleontologist D.M.S. Watson noted in 1918 that ''Conodectes'', a dubious genera named by Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

back in 1896, was likely synonymous with ''Seymouria''. Robert Broom

Robert Broom Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE (30 November 1866 6 April 1951) was a British- South African medical doctor and palaeontologist. He qualified as a medical practitioner in 1895 and received his DSc in 1905 from the University ...

(1922) argued that the genus should be referred to as ''Conodectes'' since that name was published first, but Alfred Romer (1928) objected, noting that the name ''Seymouria'' was too popular within the scientific community to be replaced. During this time, ''Seymouria'' was generally seen as a very early reptile, part of an evolutionary grade

A grade is a taxon united by a level of morphological or physiological complexity. The term was coined by British biologist Julian Huxley, to contrast with clade, a strictly phylogenetic unit.

Phylogenetics

The concept of evolutionary grades ...

known as "cotylosaurs", which also included many other stout-bodied Permian reptiles or reptile-like tetrapods.

Proposed amphibian affinities

Many paleontologists were uncertain about ''Seymouria''labyrinthodont

"Labyrinthodontia" (Greek, 'maze-toothed') is an informal grouping of extinct predatory amphibians which were major components of ecosystems in the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras (about 390 to 150 million years ago). Traditionally conside ...

" amphibians. This combination of features from reptiles (i.e. other "cotylosaurs") and amphibians (i.e. embolomeres) was evidence that ''Seymouria'' was central to the evolutionary transition between the two groups. Regardless, not enough was known about its biology to conclude which group it was truly part of. Broom (1922) and Russian paleontologist Peter Sushkin (1925) supported a placement among the Amphibia, but most studies around this time tentatively considered it an extremely "primitive" reptile; these included a comprehensive redescription of material referred to the species, published by Theodore E. White in 1939.

However, indirect evidence that ''Seymouria'' was not biologically reptilian started to emerge by the 1940s. Around this time, several newly described genera were linked to ''Seymouria'' as part of the group Seymouriamorpha

Seymouriamorpha were a small but widespread group of limbed vertebrates (tetrapods). They have long been considered stem group, stem-amniotes (reptiliomorphs), and most paleontologists still accept this point of view, but some analyses suggest th ...

. Some seymouriamorphs, such as '' Kotlassia'', had evidence of aquatic habits, and even ''Seymouria'' itself had occasionally been argued to possess lateral lines, sensory structures only usable underwater. Watson (1942) and Romer (1947) each reversed their stance on ''Seymouria''Zdeněk Špinar

Zdeněk Špinar (4 April 1916 – 14 August 1995) was a Czechoslovak paleontologist and author. He was renowned in the field for popularising vertebrate paleontology. He specialised in the paleontology of amphibians, especially anurans. Many of ...

reported gills preserved in juvenile fossils of the seymouriamorph '' Discosauriscus''. This unequivocally proved that seymouriamorphs had an aquatic larval stage, and thus were amphibians, biologically speaking. Nevertheless, the numerous similarities between ''Seymouria'' and reptiles supported the idea that seymouriamorphs were close to the ancestry of amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s.

Additional species and fossils

In 1966, Peter Paul Vaughn described an assortment of ''Seymouria'' skulls from the

In 1966, Peter Paul Vaughn described an assortment of ''Seymouria'' skulls from the Organ Rock Shale

The Organ Rock Formation or Organ Rock Shale is a formation within the late Pennsylvanian to early Permian Cutler Group and is deposited across southeastern Utah, northwestern New Mexico, and northeastern Arizona. This formation notably outcrops ar ...

of Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

. These remains represented a new species, ''Seymouria sanjuanensis''. Fossils of this species are now understood to be more abundant and widespread than those of ''Seymouria baylorensis''. Several more species were later named by Paul E. Olson, although their validity has been more questionable than that of ''S. sanjuanensis''. For example, ''Seymouria agilis'' (Olson, 1980), known from a nearly complete skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

from the Chickasha Formation of Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, was reassigned by Michel Laurin

Michel Laurin is a Canadian-born French vertebrate paleontologist whose specialities include the emergence of a land-based lifestyle among vertebrates, the evolution of body size and the origin and phylogeny of lissamphibians. He has also made impo ...

and Robert R. Reisz to the parareptile

Parareptilia ("near-reptiles") is an extinct group of Basal (phylogenetics), basal Sauropsida, sauropsids ("Reptile, reptiles"), traditionally considered the sister taxon to Eureptilia (the group that likely contains all living reptiles and birds ...

'' Macroleter'' in 2001. ''Seymouria grandis'', described a year earlier from a braincase found in Texas, has not been re-referred to any other tetrapod, but it remains poorly known. Langston (1963) reported a femur indistinguishable from that of ''S. baylorensis'' in Permian sediments at Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island is an island Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. While it is the smallest province by land area and population, it is the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

on the Eastern coast of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

. ''Seymouria''-like skeletal remains are also known from the Richards Spur

Richards Spur is a Permian fossil locality located at the Dolese Brothers Limestone Quarry north of Lawton, Oklahoma. The locality preserves clay and mudstone fissure fills of a karst system eroded out of Ordovician limestone and dolomite, with t ...

Quarry in Oklahoma, as first described by Sullivan & Reisz (1999). A block of sediment containing six ''S. sanjuanensis'' skeletons was found in the

A block of sediment containing six ''S. sanjuanensis'' skeletons was found in the Cutler Formation

The Cutler Formation or Cutler Group is a stratigraphic unit exposed across the U.S. states of Arizona, northwest New Mexico, southeast Utah and southwest Colorado. It was laid down in the Early Permian during the Wolfcampian epoch.

Desc ...

of New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

, as described by Berman, Reisz, & Eberth (1987). In 1993, Berman & Martens reported the first ''Seymouria'' remains outside of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

, when they described ''S. sanjuanensis'' fossils from the Tambach Formation of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. The Tambach Formation has produced ''S. sanjuanensi''s fossils of a similar quality to those of the Cutler Formation. For example, in 2000 Berman and his colleagues described the "Tambach Lovers", two complete and fully articulated skeletons of ''S. sanjuanensis'' fossilized lying next to each other (though it cannot be determined whether they were a couple killed during courtship). The Tambach Formation has also produced the developmentally youngest known fossils of ''Seymouria'', assisting comparisons to ''Discosauriscus'', which is known primarily from juveniles.

Description

''Seymouria'' individuals were robustly-built animals, with a large head, short neck, stocky limbs, and broad feet. Even the largest specimens were fairly small, only about 2 ft (60 cm) long. The skull was boxy and roughly triangular when seen from above, but it was lower and longer than that of most other seymouriamorphs. The vertebrae had broad, swollen neural arches (the portion above the spinal cord). As a whole the body shape was similar to that of contemporary reptiles and reptile-like tetrapods such as

''Seymouria'' individuals were robustly-built animals, with a large head, short neck, stocky limbs, and broad feet. Even the largest specimens were fairly small, only about 2 ft (60 cm) long. The skull was boxy and roughly triangular when seen from above, but it was lower and longer than that of most other seymouriamorphs. The vertebrae had broad, swollen neural arches (the portion above the spinal cord). As a whole the body shape was similar to that of contemporary reptiles and reptile-like tetrapods such as captorhinids

Captorhinidae is an extinct family of tetrapods, traditionally considered primitive reptiles, known from the late Carboniferous to the Late Permian. They had a cosmopolitan distribution across Pangea.

Description

Captorhinids are a clade of sm ...

, diadectomorphs, and parareptiles. Collectively these types of animals have been referred to as "cotylosaurs" in the past, although they do not form a clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

(a natural, relations-based grouping).

Skull

The skull was composed of many smaller plate-like bones. The configuration of skull bones present in ''Seymouria'' was very similar to that of far more ancient tetrapods and tetrapod relatives. For example, it retains an

The skull was composed of many smaller plate-like bones. The configuration of skull bones present in ''Seymouria'' was very similar to that of far more ancient tetrapods and tetrapod relatives. For example, it retains an intertemporal bone

The intertemporal bone is a paired Skull, cranial bone present in certain Sarcopterygii, sarcopterygians (lobe-finned fish) and extinct amphibian-Evolutionary grade, grade tetrapods. It lies in the rear part of the skull, behind the eyes.

Many lin ...

, which is the plesiomorphic

In phylogenetics, a plesiomorphy ("near form") and symplesiomorphy are synonyms for an ancestral character shared by all members of a clade, which does not distinguish the clade from other clades.

Plesiomorphy, symplesiomorphy, apomorphy, an ...

("primitive") condition present in animals like '' Ventastega'' and embolomeres. The skull bones were heavily textured, as was typical for ancient amphibians and captorhinid

Captorhinidae is an extinct family of tetrapods, traditionally considered primitive reptiles, known from the late Carboniferous to the Late Permian. They had a cosmopolitan distribution across Pangea.

Description

Captorhinids are a clade of ...

reptiles. In addition, the rear part of the skull had a large incision stretching along its side. This incision is termed an otic notch

Otic notches are invaginations in the posterior margin of the skull roof, one behind each orbit. Otic notches are one of the features lost in the evolution of amniotes from their tetrapod ancestors.

The notches have been interpreted as part of an ...

, and a similar incision in the same general area is common to most Paleozoic amphibians ("labyrinthodonts", as they are sometimes called), but unknown in amniotes. The lower edge of the otic notch was formed by the squamosal bone

The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestral ...

, while the upper edge was formed by downturned flange

A flange is a protruded ridge, lip or rim (wheel), rim, either external or internal, that serves to increase shear strength, strength (as the flange of a steel beam (structure), beam such as an I-beam or a T-beam); for easy attachment/transfer o ...

s of the supratemporal The supratemporal bone is a paired Skull, cranial bone present in many Tetrapod, tetrapods and Tetrapodomorpha, tetrapodomorph fish. It is part of the temporal region (the portion of the skull roof behind the eyes), usually lying medial (inwards) re ...

and tabular bones (known as otic flanges). The tabular also has a second downturned flange visible from the rear of the skull; this flange (known as an occipital flange) connected to the braincase and partially obscured the space between the braincase and the side of the skull. The development of the otic and occipital flanges is greater in ''Seymouria'' (particularly ''S. baylorensis'') than in any other seymouriamorph.

The sensory apparatus of the skull also deserves mention for an array of unique features. The orbits

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an physical body, object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an satellite, artificia ...

(eye sockets) were about midway down the length of the skull, although they were a bit closer to the snout in juveniles. They were more rhomboidal than the circular orbits of other seymouriamorphs, with an acute front edge. Several authors have noted that a few specimens of ''Seymouria'' possessed indistinct grooves present in bones surrounding the orbits and in front of the otic notch. These grooves were likely remnants of a lateral line

The lateral line, also called the lateral line organ (LLO), is a system of sensory organs found in fish, used to detect movement, vibration, and pressure gradients in the surrounding water. The sensory ability is achieved via modified epithelia ...

system, a web of pressure-sensing organs useful for aquatic animals, including the presumed larval stage of ''Seymouria''. Many specimens do not retain any remnant of their lateral lines, not even juveniles. Near the middle of the parietal bone

The parietal bones ( ) are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint known as a cranial suture, form the sides and roof of the neurocranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four bord ...

s was a small hole known as a pineal foramen, which held a sensory organ known as a parietal eye

A parietal eye (third eye, pineal eye) is a part of the epithalamus in some vertebrates. The eye is at the top of the head; is photoreceptive; and is associated with the pineal gland, which regulates circadian rhythmicity and hormone production ...

. The pineal foramen is smaller in ''Seymouria'' than in other seymouriamorphs.

The stapes

The ''stapes'' or stirrup is a bone in the middle ear of humans and other tetrapods which is involved in the conduction of sound vibrations to the inner ear. This bone is connected to the oval window by its annular ligament, which allows the f ...

, a rod-like bone which lies between the braincase and the wall of the skull, was tapered. It connected the braincase to the upper edge of the otic notch, and likely served as a conduit of vibrations received by a tympanum (eardrum) which presumably lay within the otic notch. In this way it could transmit sound from the outside world to the brain. The configuration of the stapes is intermediate between non-amniote tetrapods and amniotes. On the one hand, its connection to the otic notch is unusual, since true reptiles and other amniotes have lost an otic notch, forcing the tympanum and stapes to shift downwards towards the quadrate bone

The quadrate bone is a skull bone in most tetrapods, including amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, birds), and early synapsids.

In most tetrapods, the quadrate bone connects to the quadratojugal and squamosal bones in the skull, and forms up ...

of the jaw joint. On the other hand, the thin, sensitive structure of ''Seymouria''anterior semicircular canal

The semicircular canals are three semicircular interconnected tubes located in the innermost part of each ear, the inner ear. The three canals are the lateral, anterior and posterior semicircular canals. They are the part of the bony labyrinth, ...

was likely encompassed by a cartilaginous (rather than bony) supraoccipital. These features are more primitive than those of true reptiles and synapsids.

The palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sep ...

(roof of the mouth) had some similarities with both amniote and non-amniote tetrapods. On the one hand, it retained a few isolated large fangs with maze-like internal enamel folding, as is characteristic for "labyrinthodont" amphibians. On the other hand, the vomer

The vomer (; ) is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right maxillary bones. The vomer forms ...

bones at the front of the mouth were fairly narrow, and the adjacent choana

The choanae (: choana), posterior nasal apertures or internal nostrils are two openings found at the back of the nasal passage between the nasal cavity and the pharynx, in humans and other mammals (as well as crocodilians and most skinks). They ...

e (holes leading from the nasal cavity to the mouth) were large and close together, as in amniotes. The palate is generally solid bone, with only vestigial interpteryoid vacuities (a pair of holes adjacent to the midline) separated by a long and thin cultriform process (the front blade of the base of the braincase). Apart from the fangs, the palate is also covered with small denticles radiating out from the rear part of the pterygoid bone

The pterygoid is a paired bone forming part of the palate of many vertebrates, behind the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones (; derived from the Latin ''palatum'') are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal specie ...

s. ''Seymouria'' has a few amniote-like characteristics of the palate, such as the presence of a prong-like outer rear branch of the pterygoid (formally known as a transverse flange) as well as an epipterygoid bone which is separate from the pterygoid. However, these characteristics have been observed in various non-amniote tetrapods, so they do not signify its status as an amniote.

The lower jaw retained a few plesiomorphic characteristics. For example, the inner edge of the mandible possessed three coronoid bones. The mandible also retained at least one large hole along its inner edge known as a meckelian fenestra, although this feature was only confirmed during a 2005 re-investigation of one of the Cutler Formation specimens. Neither of these traits are the standard in amniotes. The braincase had a mosaic of features in common with various tetrapodomorphs. The system of grooves and nerve openings on the side of the braincase were unusually similar to those of the fish '' Megalichthys,'' and the cartilaginous base is another plesiomorphic feature. However, the internal carotid arteries perforate the braincase near the rear of the bone complex, a derived feature similar to amniotes.

Postcranial skeleton

The

The vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

is fairly short, with a total of 24 vertebra

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spina ...

e between the hip and skull. The vertebrae are gastrocentrous, meaning that each vertebra has a larger, somewhat spool-shaped component known as a pleurocentrum, and a smaller, wedge-shaped (or crescent-shaped from the front) component known as an intercentrum. The neural arches, which lie above the pleurocentra, are swollen into broad structures with table-like zygapophyses (joint plates) about three times as wide as the pleurocentrum itself. Some vertebrae have neural spines which are partially subdivided down the middle, while others are oval-shaped in horizontal cross-section. The ribs of the dorsal vertebrae extend horizontally and attach to the vertebrae at two places: the intercentrum and the side of the neural arch. The neck is practically absent, only a few vertebrae long. The first neck vertebra, the atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

, had a small intercentrum as well as a reduced pleurocentrum which was only present in mature individuals. Although the atlantal pleurocentrum (when present) was wedged between the intercentrum of the atlas and intercentrum of the succeeding axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

vertebra (as in amniotes), the low bone development in this area of the neck contrasts with the characteristic atlas-axis complex of amniotes. In addition, later studies found that the atlas intercentrum was divided into a left and right portion, more like that of amphibian-grade tetrapods. Unlike almost all other Paleozoic tetrapods (amniote or otherwise), ''Seymouria'' completely lacks any bony remnants of scales or scutes, not even the thin, circular belly scales of other seymouriamorphs.

The pectoral (shoulder) girdle has several reptile-like features. For example, the scapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

and coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

(bony plates which lie above and below the shoulder socket, respectively) are separate bones, rather than one large shoulder blade. Likewise, the interclavicle was flat and mushroom-shaped, with a long and thin "stem". The humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

(forearm bone) was shaped like a boxy and slightly twisted L, with large areas for muscle attachment. This form, which has been described as "tetrahedral", is plesiomorphic for tetrapods and contrasts with the slender hourglass-shaped humerus of amniotes. On the other hand, the lower part of the humerus also has a reptile-like adaptation: a hole known as an entepicondylar foramen

The entepicondylar foramen is an opening in the distal (far) end of the humerus (upper arm bone) present in some mammals. It is often present in primitive placentals, such as the enigmatic Madagascan '' Plesiorycteropus''. In most Neotominae and a ...

. The radius

In classical geometry, a radius (: radii or radiuses) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The radius of a regular polygon is th ...

was narrowest at mid-length. The ulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

is similar, but longer due to the possession of a pronounced olecranon process

The olecranon (, ), is a large, thick, curved bony process on the proximal, posterior end of the ulna. It forms the protruding part of the elbow and is opposite to the cubital fossa or elbow pit (trochlear notch). The olecranon serves as a lever ...

, as is common in terrestrial tetrapods but rare in amphibious or aquatic ones. The carpus (wrist) has ten bones, and the hand has five stout fingers. The carpal bones are fully developed and closely contact each other, another indication of terrestriality. The phalanges (finger bones) decrease in size towards the tip of the fingers, where they each end in a tiny, rounded segment, without a claw. The phalangeal formula (number of phalanges per finger, from thumb to little finger) is 2-3-4-4-3.

Two sacral (hip) vertebrae were present, though only the first one possessed a large, robust rib which contacted the ilium (upper blade of the hip). Some studies have argued that there was only one sacral vertebra, with the supposed second sacral actually being the first caudal due to having a shorter, more curved rib than the first sacral. Each ilium is low and teardrop-shaped when seen from the side, while the underside of the hip as a whole is formed by a single robust puboischiadic plate, which is rectangular when seen from below. Both the hip and shoulder sockets were directed at 45 degrees below the horizontal. The femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

is equally stout as the humerus, and the tibia

The tibia (; : tibiae or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two Leg bones, bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outsi ...

and fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

are robust, hourglass-shaped bones similar to the radius and ulna. The tarsus (ankle) incorporates 11 bones, intermediate between earlier tetrapods (which have 12) and amniotes (which have 8 or fewer). The five-toed feet are quite similar to the hands, with phalangeal formula 2-3-4-5-3.

There were only about 20 caudal (tail) vertebrae at most. Past the base of the tail, the caudals start to acquire bony spines along their underside, known as chevrons. These begin to appear in the vicinity of the third to sixth caudal, depending on the specimen. Ribs are only present within the first five or six caudals; they are long at the base of the tail but diminish soon afterwards and typically disappear around the same area the chevrons appear.

Differences between species

''Seymouria baylorensis'' and ''Seymouria sanjuanensis'' can be distinguished from each other based on several differences in the shape and connections between the different bones of the skull. For example, the downturned flange of bone above the otic notch (sometimes termed the "tabular horn" or "otic process") is much more well-developed in ''S. baylorensis'' than in ''S. sanjuanensis''. In the former species, it acquires a triangular shape (when seen from the side) as it extends downwards more extensively towards the rear of the skull. In ''S. sanjuanensis'', the postfrontal bone contacts theparietal bone

The parietal bones ( ) are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint known as a cranial suture, form the sides and roof of the neurocranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four bord ...

by means of an obtuse, wedge-like suture, while the connection between the two bones is completely straight in ''S. baylorensis''.  Some authors have argued that the postparietals of ''S. baylorensis'' were smaller than those of ''S. sanjuanensis'', but some specimens of ''S. sanjuanensis'' (for example, the "Tambach lovers") also had small postparietals. In addition, the "Tambach lovers" have a

Some authors have argued that the postparietals of ''S. baylorensis'' were smaller than those of ''S. sanjuanensis'', but some specimens of ''S. sanjuanensis'' (for example, the "Tambach lovers") also had small postparietals. In addition, the "Tambach lovers" have a quadratojugal bone The quadratojugal is a skull bone present in many vertebrates, including some living reptiles and amphibians.

Anatomy and function

In animals with a quadratojugal bone, it is typically found connected to the jugal (cheek) bone from the front and ...

which is more similar to that of ''S. baylorensis'' rather than ''S. sanjuanensis''. The combination of features from both species in these specimens may indicate that the two species are part of a continuous lineage, rather than two divergent evolutionary paths. Likewise, some differences relating to the proportions of the rear of the skull may be considered to be an artifact of the fact that most ''S. sanjuanensis'' specimens were not fully grown prior to the discovery of the "Tambach lovers", which were adult members of the species.

Nevertheless, several traits are still clearly differentiated between the two species. The lacrimal bone

The lacrimal bones are two small and fragile bones of the facial skeleton; they are roughly the size of the little fingernail and situated at the front part of the medial wall of the orbit. They each have two surfaces and four borders. Several bon ...

, in front of the eyes, only occupies the front edge of the orbit in ''S. baylorensis''. Conversely, specimens of ''S. sanjuanensis'' have a branch of the lacrimal which extends a small distance under the orbit. In ''S. sanjuanensis'', much of the rear edge of the orbit is formed by the chevron-shaped postorbital bone

The ''postorbital'' is one of the bones in vertebrate skulls which forms a portion of the dermal skull roof and, sometimes, a ring about the orbit. Generally, it is located behind the postfrontal and posteriorly to the orbital fenestra. In some ...

, which is more rectangular in ''S. baylorensis''. The shape of the lacrimal and postorbital of ''S. sanjuanensis'' closely corresponds to the condition in other seymouriamorphs, while the condition in ''S. baylorensis'' is more unique and derived.

The tooth-bearing maxilla bone, which forms the side of the snout, is also distinctively unique in ''S. baylorensis''. In ''S. sanjuanensis'', the maxilla was low, with many sharp, closely spaced teeth extending along its length. This condition is similar to other seymouriamorphs. However, ''S. baylorensis'' has a taller snout, and its teeth are generally much larger, less numerous, and less homogenous in size. The palate is generally similar between the two species, although the ectopterygoids are more triangular in ''S. baylorensis'' and rectangular in ''S. sanjuanensis''.

Paleobiology

Lifestyle

Romer (1928) was among the first authors to discuss the biological implications of ''Seymouria''amnion

The amnion (: amnions or amnia) is a membrane that closely covers human and various other embryos when they first form. It fills with amniotic fluid, which causes the amnion to expand and become the amniotic sac that provides a protective envir ...

membrane.

White (1939) elaborated on biological implications. He noted that the presence of an otic notch reduces jaw strength by lowering the amount of surface area jaw muscles can attach to within the cranium. In addition, the skull would have been more fragile due to the presence of such a large incision. As a whole, he found it unlikely that ''Seymouria'' was capable of tackling large, active prey. Nevertheless, the sites for muscle attachment on the palate were more well-developed than those of contemporaneous amphibians. White extrapolated that ''Seymouria'' was a mostly carnivorous generalist and omnivore, feeding on invertebrates, small fish, and perhaps even some plant material. It may have even been cannibalistic according to his reckoning.

White also drew attention to the unusual swollen vertebrae, which would have facilitated lateral (side-to-side) movement but prohibit any torsion (twisting) of the backbone. This would have been beneficial, since ''Seymouria'' had low-slung limbs and a wide, top-heavy body that would have otherwise been vulnerable to torsion when it was walking. This may also explain the presence of this trait in captorhinids, diadectomorphs, and other "cotylosaurs". Perhaps swollen vertebrae were an interim strategy to prevent torsion, which would later be supplanted by strong hip muscles in later reptiles. The rather undeveloped hip muscles of ''Seymouria'' are in line with this hypothesis. Nevertheless, these vertebrae were inefficient at defending against torsion at any speed faster than a brisk walk, so ''Seymouria'' was probably not a quick-moving animal.

Although White considered ''Seymoria'' to be quite competent on land, he also discussed a few other lifestyles. He supposed that ''Seymouria'' was also a good swimmer, since he (erroneously) estimated that the animal had a deep and powerful tail similar to that of modern crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

ns. However, he also noted that it would have been vulnerable to semiaquatic or aquatic predators, and that ''Seymouria'' fossils were more common in terrestrial deposits as a result of its habitat preferences. Berman ''et al''. (2000) supported this hypothesis, as the Tambach Formation preserved ''Seymouria'' fossils while also completely lacking aquatic animals. They also pointed out the well-developed wrist and ankle bones of the "Tambach lovers" as supportive of terrestrial affinities. Despite the strong musculature of the forelimbs, Romer (1928) and White (1939) found little evidence for burrowing adaptations in ''Seymouria''.

Sexual dimorphism

Some authors have argued in favor ofsexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

existing in ''Seymouria'', but others are unconvinced by this hypothesis. White (1939) argued that some specimens of ''Seymouria baylorensis'' had chevrons (bony spines on the underside of the tail vertebrae) which first appeared on the third tail vertebra, while other specimens had them first appear on the sixth. He postulated that the later appearance of the chevrons in some specimens was indicative that they were males in need of more space to store their internal genitalia. This type of sexual differentiation has been reported in both turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s and crocodilians. Based on this, he also supported the idea that ''Seymouria'' females gave birth to large-yolked eggs on land, as with turtles and crocodilians. Vaughn (1966) later found a correlation between chevron acquisition and certain skull proportions in ''Seymouria sanjuanensis'', and proposed that they too were examples of sexual dimorphism.

However, Berman, Reisz, & Elberth (1987) criticized the methodologies of White (1939) and Vaughn (1966). They argued that White's observations were probably unrelated to the sex of the animals. This was supported by the fact that some of the Cutler Formation specimens had chevrons which first appeared on their fifth tail vertebra. Although it was possible that genital size was variable among males to the extent of impacting the skeleton, the more likely explanation was that the differences White had observed were caused by individual skeletal variation, evolutionary divergence, or some other factor unrelated to sexual dimorphism. Likewise, they agreed that skull proportions supported Vaughn (1966)'s proposal that dimorphism was present in ''Seymouria'' fossils, though they disagreed with how he linked it to sex using a fossil which was considered "female" under White's criteria. The discovery of fossilized larval seymouriamorphs has shown that ''Seymouria'' likely had an aquatic larval stage, debunking earlier hypotheses that ''Seymouria'' laid eggs on land.

Histology and development

Histological

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology that studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissue (biology), tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at large ...

evidence from specimens found in Richards Spur

Richards Spur is a Permian fossil locality located at the Dolese Brothers Limestone Quarry north of Lawton, Oklahoma. The locality preserves clay and mudstone fissure fills of a karst system eroded out of Ordovician limestone and dolomite, with t ...

s, Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

has provided additional information on ''Seymouria''lissamphibia

The Lissamphibia (from Greek λισσός (lissós, "smooth") + ἀμφίβια (amphíbia), meaning "smooth amphibians") is a group of tetrapods that includes all modern amphibians. Lissamphibians consist of three living groups: the Salientia ( ...

ns, the medullary cavity

The medullary cavity (''medulla'', innermost part) is the central cavity of bone shafts where red bone marrow and/or yellow bone marrow (adipose tissue) is stored; hence, the medullary cavity is also known as the marrow cavity.

Located in the ma ...

is open and has a small amount of spongiosa bone. The development of spongiosa bone is slightly higher that of '' Acheloma'' (a terrestrial amphibian), but is much less extensive than aquatic amphibians such as '' Rhinesuchus'' and '' Trimerorhachis''. ''Seymouria''References

External links

A photograph of the "Tambach lovers" specimen, published by Mark MacDougall's twitter account

{{Taxonbar, from=Q131455 Seymouriamorpha Cisuralian tetrapods of Europe Cisuralian tetrapods of North America Fossil taxa described in 1904