Price discrimination is a

microeconomic

Microeconomics is a branch of mainstream economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. Microeconomics foc ...

pricing strategy

A business can use a variety of pricing strategies when selling a product or service. To determine the most effective pricing strategy for a company, senior executives need to first identify the company's pricing position, pricing segment, pricin ...

where identical or largely similar goods or services are sold at different

price

A price is the (usually not negative) quantity of payment or compensation given by one party to another in return for goods or services. In some situations, the price of production has a different name. If the product is a "good" in t ...

s by the same provider in

different markets.

Price discrimination is distinguished from

product differentiation

In economics and marketing, product differentiation (or simply differentiation) is the process of distinguishing a product or service from others to make it more attractive to a particular target market. This involves differentiating it from co ...

by the more substantial difference in

production cost

Cost of goods sold (COGS) is the carrying value of goods sold during a particular period.

Costs are associated with particular goods using one of the several formulas, including specific identification, first-in first-out (FIFO), or average cost. ...

for the differently priced products involved in the latter strategy.

Price differentiation essentially relies on the variation in the customers'

willingness to pay

In behavioral economics, willingness to pay (WTP) is the maximum price at or below which a consumer

A consumer is a person or a group who intends to order, or uses purchased goods, products, or services primarily for personal, social, famil ...

[Apollo, M. (2014). Dual Pricing–Two Points of View (Citizen and Non-citizen) Case of Entrance Fees in Tourist Facilities in Nepal. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 120, 414-422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.119] and in the

elasticity of their demand. For price discrimination to succeed, a firm must have market power, such as a dominant market share, product uniqueness, sole pricing power, etc. All prices under price discrimination are higher than the equilibrium price in a perfectly-competitive market. However, some prices under price discrimination may be lower than the price charged by a single-price monopolist.

The term ''differential pricing'' is also used to describe the practice of charging different prices to different buyers for the same quality and quantity of a product,

but it can also refer to a combination of price differentiation and product differentiation.

Other terms used to refer to price discrimination include "equity pricing", "preferential pricing",

"dual pricing"

and "tiered pricing".

Within the broader domain of price differentiation, a commonly accepted classification dating to the 1920s is:

* "Personalized pricing" (or first-degree price differentiation) — selling to each customer at a different price; this is also called

one-to-one marketing

Personalized marketing, also known as one-to-one marketing or individual marketing, is a marketing strategy by which companies leverage data analysis and digital technology to deliver individualized messages and product offerings to current or pr ...

.

The optimal incarnation of this is called "perfect price discrimination" and maximizes the price that each customer is willing to pay.

* "Product versioning"

or simply "versioning" (or second-degree price differentiation) — offering a

product line

Product may refer to:

Business

* Product (business), an item that serves as a solution to a specific consumer problem.

* Product (project management), a deliverable or set of deliverables that contribute to a business solution

Mathematics

* Prod ...

by creating slightly different products for the purpose of price differentiation,

i.e. a ''vertical'' product line.

Another name given to versioning is "menu pricing".

* "Group pricing" (or third-degree price differentiation) — dividing the market into segments and charging a different price to each segment (but the same price to each member of that segment).

This is essentially a heuristic approximation that simplifies the problem in face of the difficulties with personalized

pricing

Pricing is the process whereby a business sets the price at which it will sell its products and services, and may be part of the business's marketing plan. In setting prices, the business will take into account the price at which it could acq ...

.

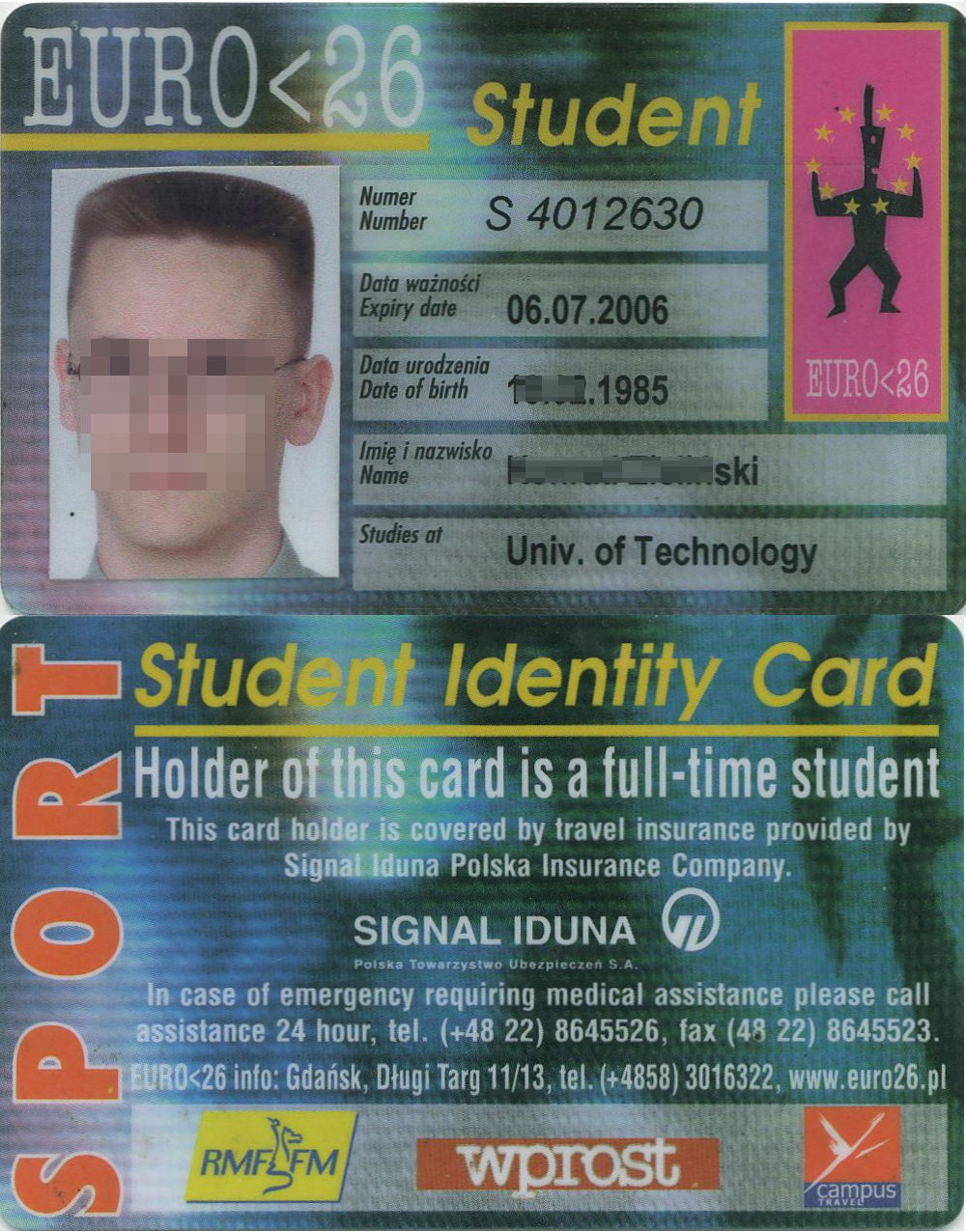

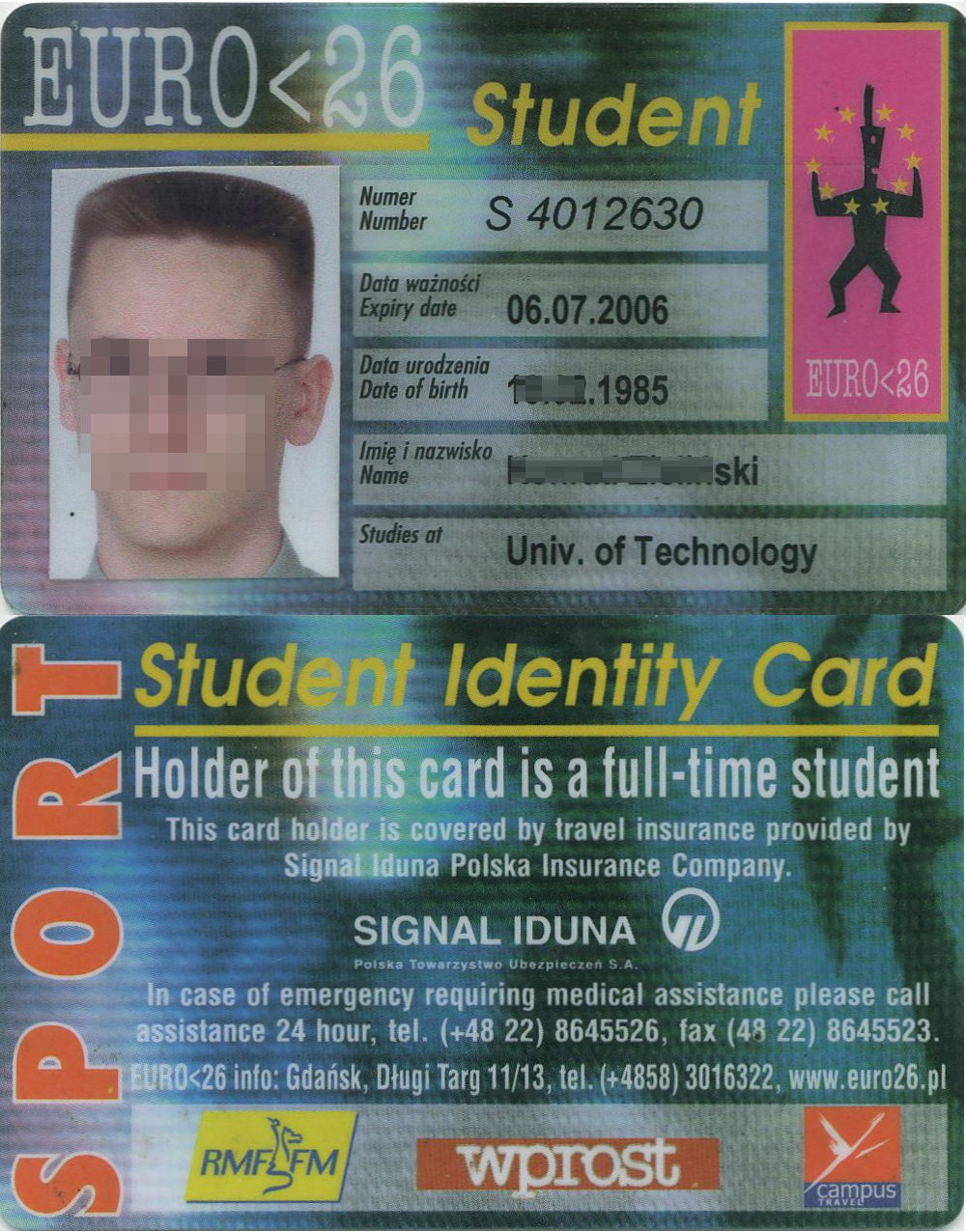

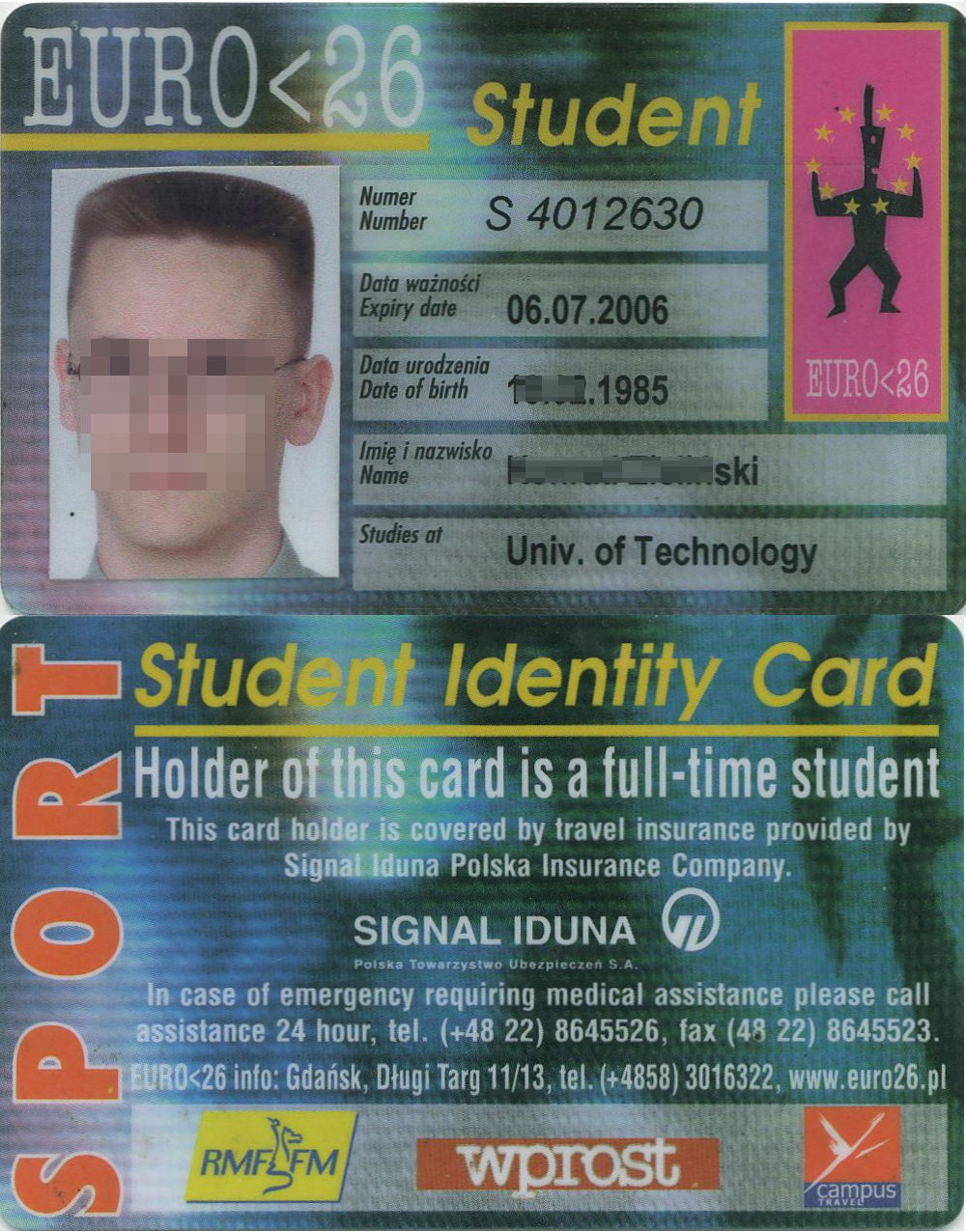

Typical examples include

student discount

Discounts and allowances are reductions to a basic price of goods or services.

They can occur anywhere in the distribution channel, modifying either the manufacturer's list price (determined by the manufacturer and often printed on the package ...

s

and seniors' discounts.

Theoretical basis

In a theoretical market with

perfect information

In economics, perfect information (sometimes referred to as "no hidden information") is a feature of perfect competition. With perfect information in a market, all consumers and producers have complete and instantaneous knowledge of all market pr ...

,

perfect substitutes, and no

transaction cost

In economics and related disciplines, a transaction cost is a cost in making any economic trade when participating in a market. Oliver E. Williamson defines transaction costs as the costs of running an economic system of companies, and unlike pro ...

s or prohibition on secondary exchange (or re-selling) to prevent

arbitrage

In economics and finance, arbitrage (, ) is the practice of taking advantage of a difference in prices in two or more markets; striking a combination of matching deals to capitalise on the difference, the profit being the difference between t ...

, price discrimination can only be a feature of

monopolistic

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

and

oligopolistic

An oligopoly (from Greek ὀλίγος, ''oligos'' "few" and πωλεῖν, ''polein'' "to sell") is a market structure in which a market or industry is dominated by a small number of large sellers or producers. Oligopolies often result fro ...

markets, where

market power

In economics, market power refers to the ability of a firm to influence the price at which it sells a product or service by manipulating either the supply or demand of the product or service to increase economic profit. In other words, market pow ...

can be exercised. Otherwise, the moment the seller tries to sell the same good at different prices, the buyer at the lower price can arbitrage by selling to the consumer buying at the higher price but with a tiny discount. However, product heterogeneity,

market frictions or high fixed costs (which make marginal-cost pricing unsustainable in the long run) can allow for some degree of differential pricing to different consumers, even in fully competitive retail or industrial markets.

The effects of price discrimination on

social efficiency

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

are unclear. Output can be expanded when price discrimination is very efficient. Even if output remains constant, price discrimination can reduce efficiency by misallocating output among consumers.

Price discrimination requires

market segmentation

In marketing, market segmentation is the process of dividing a broad consumer or business market, normally consisting of existing and potential customers, into sub-groups of consumers (known as ''segments'') based on some type of shared charact ...

and some means to discourage discount customers from becoming resellers and, by extension, competitors. This usually entails using one or more means of preventing any resale: keeping the different price groups separate, making price comparisons difficult, or restricting pricing information. The boundary set up by the marketer to keep segments separate is referred to as a ''rate fence''. Price discrimination is thus very common in services where resale is not possible; an example is student discounts at museums: In theory, students, for their condition as students, may get lower prices than the rest of the population for a certain product or service, and later will not become resellers, since what they received, may only be used or consumed by them. Another example of price discrimination is

intellectual property

Intellectual property (IP) is a category of property that includes intangible creations of the human intellect. There are many types of intellectual property, and some countries recognize more than others. The best-known types are patents, cop ...

, enforced by law and by technology. In the market for DVDs, laws require DVD players to be designed and produced with hardware or software that prevents inexpensive copying or playing of content purchased legally elsewhere in the world at a lower price. In the US the

Digital Millennium Copyright Act

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) is a 1998 United States copyright law that implements two 1996 treaties of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). It criminalizes production and dissemination of technology, devices, or ...

has provisions to outlaw circumventing of such devices to protect the enhanced monopoly profits that copyright holders can obtain from price discrimination against higher price market segments.

Price discrimination can also be seen where the requirement that goods be identical is relaxed. For example, so-called "premium products" (including relatively simple products, such as cappuccino compared to regular coffee with cream) have a price differential that is not explained by the cost of production. Some economists have argued that this is a form of price discrimination exercised by providing a means for consumers to reveal their willingness to pay.

Price discrimination differentiates the willingness to pay of the customers, in order to eliminate as much consumer surplus as possible. By understanding the elasticity of the customer's demand, a business could use its market power to identify the customers' willingness to pay. Different people would pay a different price for the same product when price discrimination exists in the market. When a company recognized a consumer that has a lower willingness to pay, the company could use the price discrimination strategy in order to maximized the firm's profit.

First degree

Exercising first degree (or perfect or primary) price discrimination requires the monopoly seller of a good or service to know the absolute maximum price (or

reservation price

In economics, a reservation (or reserve) price is a limit on the price of a good or a service. On the demand side, it is the highest price that a buyer is willing to pay; on the supply side, it is the lowest price a seller is willing to accept ...

) that every consumer is willing to pay. By knowing the reservation price, the seller is able to sell the good or service to each consumer at the maximum price they are willing to pay, and thus transform the

consumer surplus

In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or total social welfare or Marshallian surplus (after Alfred Marshall), is either of two related quantities:

* Consumer surplus, or consumers' surplus, is the monetary gain ...

into revenues, leading it to be the most profitable form of price discrimination. So the profit is equal to the sum of consumer surplus and

producer surplus

In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or total social welfare or Marshallian surplus (after Alfred Marshall), is either of two related quantities:

* Consumer surplus, or consumers' surplus, is the monetary gain ...

. First-degree price discrimination is the most profitable as it obtains all of the consumer surplus and each consumer buys the good at the highest price they are willing to pay. The marginal consumer is the one whose reservation price equals the marginal cost of the product, meaning that the social surplus comes entirely from producer surplus, which is obviously beneficial for the firm. The seller produces more of their product than they would achieve monopoly profits with no price discrimination, which means that there is no

deadweight loss

In economics, deadweight loss is the difference in production and consumption of any given product or service including government tax. The presence of deadweight loss is most commonly identified when the quantity produced ''relative'' to the amoun ...

. During first-degree price discrimination, the firm produces the amount where marginal benefit equals marginal cost, and fully maximizes producer surplus. Examples of this might be observed in markets where consumers bid for tenders, though, in this case, the practice of collusive tendering could reduce the market efficiency.

Second degree

In second-degree price discrimination, price varies according to quantity demanded. Larger quantities are available at a lower unit price. This is particularly widespread in sales to industrial customers, where bulk buyers enjoy discounts.

Additionally to second-degree price discrimination, sellers are not able to differentiate between different types of consumers. Thus, the suppliers will provide incentives for the consumers to differentiate themselves according to preference, which is done by quantity "discounts", or non-linear pricing. This allows the supplier to set different prices to the different groups and capture a larger portion of the total market surplus.

In reality, different pricing may apply to differences in product quality as well as quantity. For example, airlines often offer multiple classes of seats on flights, such as first-class and economy class, with the first-class passengers receiving wine, beer and spirits with their ticket and the economy passengers offered only juice, pop, and water. This is a way to differentiate consumers based on preference, and therefore allows the airline to capture more consumer's surplus.

Third degree

Third-degree price discrimination means charging a different price to different consumers in a given number of groups and being able to distinguish between the groups to charge a separate monopoly price. For example, rail and tube (subway) travelers can be subdivided into commuters and casual travelers, and cinema goers can be subdivided into adults and children, with some theatres also offering discounts to full-time students and seniors. Splitting the market into peak and off-peak use of service is very common and occurs with gas, electricity, and telephone supply, as well as gym membership and parking charges. Some parking lots charge less for "early bird" customers who arrive at the parking lot before a certain time.

(Some of these examples are not pure "price discrimination", in that the differential price is related to production costs: the marginal cost of providing electricity or car parking spaces is very low outside peak hours. Incentivizing consumers to switch to off-peak usage is done as much to minimize costs as to maximize revenue.)

There are limits for price discrimination as well. When price discrimination exists in a market, the consumer surplus and producer surplus will be affected by its existence. In order to offer different prices for different groups of people in the aggregate market, the business has to use additional information to identify its consumers. Consequently, they will be involved in third-degree price discrimination. With third-degree price discrimination, the firms try to generate sales by identifying different market segments, such as domestic and industrial users, with different price elasticities. Markets must be kept separate by time, physical distance, and nature of use. For example, Microsoft Office Schools edition is available for a lower price to educational institutions than to other users. The markets cannot overlap so that consumers who purchase at a lower price in the elastic sub-market could resell at a higher price in the inelastic sub-market. The company must also have monopoly power to make price discrimination more effective.

Two-part tariff

The

two-part tariff is another form of price discrimination where the producer charges an initial fee and a secondary fee for the use of the product. This pricing strategy yields a result similar to second-degree price discrimination. An example of two-part tariff pricing is in the market for

shaving razors. The customer pays an initial cost for the razor and then pays again for the replacement blades. This pricing strategy works because it shifts the demand curve to the right: since the customer has already paid for the initial blade holder and will continue to buy the blades which are cheaper than buying disposable razors.

Combination

These types are not mutually exclusive. Thus a company may vary pricing by location, but then offer bulk discounts as well. Airlines use several different types of price discrimination, including:

* Bulk discounts to wholesalers, consolidators, and tour operators

* Incentive discounts for higher sales volumes to travel agents and corporate buyers

* Seasonal discounts, incentive discounts, and even general prices that vary by location. The price of a flight from say, Singapore to Beijing can vary widely if one buys the ticket in Singapore compared to Beijing (or New York or Tokyo or elsewhere).

* Discounted tickets requiring advance purchase and/or Saturday stays. Both restrictions have the effect of excluding business travelers, who typically travel during the workweek and arrange trips on shorter notice.

* First degree price discrimination based on customer. Hotel or car rental firms may quote higher prices to their loyalty program's top tier members than to the general public.

Modern taxonomy

The first/second/third degree taxonomy of price discrimination is due to Pigou (''Economics of Welfare'', 3rd edition, 1929). However, these categories are not mutually exclusive or exhaustive. Ivan Png (''Managerial Economics'', 1998: 301-315) suggests an alternative taxonomy:

;Complete discrimination: where the seller prices each unit at a different price, so that each user purchases up to the point where the user's marginal benefit equals the marginal cost of the item;

;Direct segmentation: where the seller can condition price on some attribute (like age or gender) that ''directly'' segments the buyers;

;Indirect segmentation: where the seller relies on some proxy (e.g., package size, usage quantity, coupon) to structure a choice that ''indirectly'' segments the buyers;

;Uniform pricing: where the seller sets the same price for each unit of the product.

The hierarchy—complete/direct/indirect/uniform pricing—is in decreasing order of profitability and information requirement. Complete price discrimination is most profitable, and requires the seller to have the most information about buyers. Next most profitable and in information requirement is direct segmentation, followed by indirect segmentation. Finally, uniform pricing is the least profitable and requires the seller to have the least information about buyers is.

Explanation

The purpose of price discrimination is generally to capture the market's

consumer surplus

In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or total social welfare or Marshallian surplus (after Alfred Marshall), is either of two related quantities:

* Consumer surplus, or consumers' surplus, is the monetary gain ...

. This surplus arises because, in a market with a single clearing price, some customers (the very low price elasticity segment) would have been prepared to pay more than the single market price. Price discrimination transfers some of this surplus from the consumer to the producer/marketer. It is a way of increasing

monopoly profit

Monopoly profit is an inflated level of profit due to the monopolistic practices of an enterprise.Bradley R. Chiller, "Essentials of Economics", New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1991.

Basic classical and neoclassical theory

Traditional economics sta ...

. In a perfectly-competitive market, manufacturers make

normal profit

In economics, profit is the difference between the revenue that an economic entity has received from its outputs and the total cost of its inputs. It is equal to total revenue minus total cost, including both explicit and implicit costs.

It ...

, but not

monopoly profit

Monopoly profit is an inflated level of profit due to the monopolistic practices of an enterprise.Bradley R. Chiller, "Essentials of Economics", New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1991.

Basic classical and neoclassical theory

Traditional economics sta ...

, so they cannot engage in price discrimination.

It can be argued that strictly, a consumer surplus need not exist, for example where fixed costs or

economies of scale

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of output produced per unit of time. A decrease in cost per unit of output enables a ...

mean that the

marginal cost

In economics, the marginal cost is the change in the total cost that arises when the quantity produced is incremented, the cost of producing additional quantity. In some contexts, it refers to an increment of one unit of output, and in others it r ...

of adding more consumers is less than the

marginal profit

In microeconomics, marginal profit is the increment to profit resulting from a unit or infinitesimal increment to the quantity of a product produced. Under the marginal approach to profit maximization, to maximize profits, a firm should contin ...

from selling more product. This means that charging some consumers less than an even share of costs can be beneficial. An example is a high-speed internet connection shared by two consumers in a single building; if one is willing to pay less than half the cost of connecting the building, and the other willing to make up the rest but not to pay the entire cost, then price discrimination can allow the purchase to take place. However, this will cost the consumers as much or more than if they pooled their money to pay a non-discriminating price. If the consumer is considered to be the building, then a consumer surplus goes to the inhabitants.

It can be proved mathematically that a firm facing a downward sloping demand curve that is convex to the origin will always obtain higher revenues under price discrimination than under a single price strategy. This can also be shown geometrically.

In the top diagram, a single price

is available to all customers. The amount of revenue is represented by area

. The consumer surplus is the area above line segment

but below the demand curve

.

With price discrimination, (the bottom diagram), the demand curve is divided into two segments (

and

). A higher price

is charged to the low elasticity segment, and a lower price

is charged to the high elasticity segment. The total revenue from the first segment is equal to the area

. The total revenue from the second segment is equal to the area

. The sum of these areas will always be greater than the area without discrimination assuming the demand curve resembles a rectangular hyperbola with unitary elasticity. The more prices that are introduced, the greater the sum of the revenue areas, and the more of the consumer surplus is captured by the producer.

The above requires both first and second degree price discrimination: the right segment corresponds partly to different people than the left segment, partly to the same people, willing to buy more if the product is cheaper.

It is very useful for the price discriminator to determine the optimum prices in each market segment. This is done in the next diagram where each segment is considered as a separate market with its own demand curve. As usual, the profit maximizing output (Qt) is determined by the intersection of the marginal cost curve (MC) with the marginal revenue curve for the total market (MRt).

The firm decides what amount of the total output to sell in each market by looking at the intersection of marginal cost with marginal revenue (

profit maximization

In economics, profit maximization is the short run or long run process by which a firm may determine the price, input and output levels that will lead to the highest possible total profit (or just profit in short). In neoclassical economic ...

). This output is then divided between the two markets, at the equilibrium marginal revenue level. Therefore, the optimum outputs are

and

. From the demand curve in each market the profit can be determined maximizing prices of

and

.

The marginal revenue in both markets at the optimal output levels must be equal, otherwise the firm could profit from transferring output over to whichever market is offering higher marginal revenue.

Given that Market 1 has a

price elasticity of demand

A good's price elasticity of demand (E_d, PED) is a measure of how sensitive the quantity demanded is to its price. When the price rises, quantity demanded falls for almost any good, but it falls more for some than for others. The price elastici ...

of

and Market 2 of

, the optimal pricing ration in Market 1 versus Market 2 is

Price discrimination is a

Price discrimination is a  The firm decides what amount of the total output to sell in each market by looking at the intersection of marginal cost with marginal revenue (

The firm decides what amount of the total output to sell in each market by looking at the intersection of marginal cost with marginal revenue (

Price discrimination is a

Price discrimination is a