Scottish Americans or Scots Americans (; ) are

Americans

Americans are the Citizenship of the United States, citizens and United States nationality law, nationals of the United States, United States of America.; ; Law of the United States, U.S. federal law does not equate nationality with Race (hu ...

whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

.

Scottish Americans are closely related to

Scotch-Irish Americans

Scotch-Irish Americans are American descendants of primarily Ulster Scots people, who emigrated from Ulster (Ireland's northernmost province) to the United States between the 18th and 19th centuries, with their ancestors having originally mig ...

, descendants of

Ulster Scots Ulster Scots, may refer to:

* Ulster Scots people

* Ulster Scots dialect

Ulster Scots or Ulster-Scots (), also known as Ulster Scotch and Ullans, is the dialect (whose proponents assert is a dialect of Scots language, Scots) spoken in parts ...

, and communities emphasize and celebrate a common heritage.

[Celeste Ray, 'Introduction', p. 6, id., 'Scottish Immigration and Ethnic Organization in the United States', pp. 48-9, 62, 81, in id. (ed.), ''The Transatlantic Scots'' (Tuscaloosa, AL:]University of Alabama Press

The University of Alabama Press is a university press founded in 1945 and is the scholarly publishing arm of the University of Alabama. An editorial board composed of representatives from all doctoral degree granting public universities within Al ...

, 2005). The majority of Scotch-Irish Americans originally came from Lowland Scotland and Northern England before migrating to the province of

Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

in

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

(see ''

Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster (; Ulster Scots dialects, Ulster Scots: ) was the organised Settler colonialism, colonisation (''Plantation (settlement or colony), plantation'') of Ulstera Provinces of Ireland, province of Irelandby people from Great ...

'') and thence, beginning about five

generation

A generation is all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively. It also is "the average period, generally considered to be about 20–30 years, during which children are born and grow up, become adults, and b ...

s later, to North America in large numbers during the eighteenth century. The number of Scottish Americans is believed to be around 25 million, and celebrations of

Scottish identity can be seen through

Tartan Day

Tartan Day is a celebration of Scottish heritage and the cultural contributions of Scottish and Scottish-diaspora figures of history. The name refers to tartan, a patterned woollen cloth associated with Scotland. The event originated in Nova ...

parades,

Burns Night celebrations, and

Tartan Kirking ceremonies.

Significant emigration from Scotland to America began in the 1700s, accelerating after the

Jacobite rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745 was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the Monarchy of Great Britain, British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, when the bulk of t ...

, the steady degradation of clan structures, and the

Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances ( , the "eviction of the Gaels") were the evictions of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, mostly in two phases from 1750 to 1860.

The first phase resulted from Scottish Agricultural R ...

. Even higher rates of emigration occurred after these times of social upheaval. In the 1920s, Scotland experienced a reduction in total population of 0.8%, totally absorbing the natural population increase of 7.2%: the U.S. and Canada were the most common destinations of these emigrants. Despite emphasis on the struggles and 'forced exile' of Jacobites and Highland clansmen in popular media, Scottish migration was mostly from the Lowland regions and its pressures included poverty and land clearance but also the variety of positive economic opportunities believed to be available.

Numbers

The table shows the ethnic Scottish population in the British colonies from 1700 to 1775. In 1700 the total population of the colonies was 250,888, of whom 223,071 (89%) were white and 3.0% were ethnically Scottish.

1790 population of Scottish and Scotch-Irish origin by state

Population estimates are as follows.

Data results per census

The number of Americans of Scottish descent today is estimated to be 20 to 25 million

(up to 8.3% of the total U.S. population).

The majority of Scotch-Irish Americans originally came from Lowland Scotland and Northern England before migrating to the province of

Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

in

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

(see ''

Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster (; Ulster Scots dialects, Ulster Scots: ) was the organised Settler colonialism, colonisation (''Plantation (settlement or colony), plantation'') of Ulstera Provinces of Ireland, province of Irelandby people from Great ...

'') and thence, beginning about five

generation

A generation is all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively. It also is "the average period, generally considered to be about 20–30 years, during which children are born and grow up, become adults, and b ...

s later, to North America in large numbers during the eighteenth century.

In the 2000 census, 4.8 million Americans self-reported Scottish ancestry, 1.7% of the total U.S. population.

Over 4.3 million self-reported

Scotch-Irish ancestry, for a total of 9.2 million Americans self-reporting some kind of Scottish descent.

Self-reported numbers are regarded by demographers as massive under-counts, because Scottish ancestry is known to be disproportionately under-reported among the majority of mixed ancestry,

[Mary C. Walters, ''Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), pp. 31-6.] and because areas where people reported "American" ancestry were the places where, historically, Scottish and Scotch-Irish

Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

settled in North America (that is: along the North American coast,

Appalachia

Appalachia ( ) is a geographic region located in the Appalachian Mountains#Regions, central and southern sections of the Appalachian Mountains in the east of North America. In the north, its boundaries stretch from the western Catskill Mountai ...

, and the Southeastern

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

). Scottish Americans descended from nineteenth-century Scottish emigrants tend to be concentrated in the West, while many in

New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

are the descendants of emigrants, often Gaelic-speaking, from the

Maritime Provinces

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of ...

of

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, from the 1880s onward.

Americans of Scottish descent outnumber the population of Scotland, where 4,459,071 or 88.09% of people identified as ethnic Scottish in the 2001 Census.

Scottish origins by state

The states with the largest populations of either

Scottish or

Scotch Irish ancestral origin:

*

California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

- 677,055 (1.7% of state population)

*

Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

- 628,610 (2.8%)

*

North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

- 475,322 (4.5%)

*

Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

- 469,782 (2.3%)

*

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

- 325,588 (2.5%)

*

Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

- 314,214 (2.7%)

*

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

- 293,211 (2.8%)

*

Washington - 289,953 (3.0%)

The states with the top percentages of Scottish or Scotch-Irish residents:

*

Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

(6.0% of state population)

*

Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...

(5.5%)

*

New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

(5.3%)

*

Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

(5.0%)

*

Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

and

North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

(4.5% each)

*

South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

(4.4%)

*

Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

and

Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

(4.2% each)

*

Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

(4.0%)

The

metropolitan and

micropolitan areas with the top percentage of Scottish or Scotch-Irish residents:

*

Boone, NC (9.1% of micropolitan area population)

*

Barre, VT and

Sevierville, TN (8.3% each)

*

Asheville, NC (8.1%)

*

Marion, NC and

Pinehurst-Southern Pines, NC (7.7% each)

*

Jackson, WY and

Lebanon, NH (7.0%)

*

Cullowhee, NC (6.8%)

*

Craig, CO (6.5% each)

*

Morehead City, NC,

Morristown, TN and

Sandpoint, ID

Sandpoint is the largest city in, and the county seat of, Bonner County, Idaho, Bonner County, Idaho, United States. Its population was 9,777 as of the 2022 United States census, census.

Sandpoint's major economic contributors include forest pr ...

(6.4% each)

2020 population of Scottish ancestry by state

As of 2020, the distribution of Scottish Americans across the 50 states and DC is as presented in the following table.

Historical contributions

Explorers

The first Scots in

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

came with the

Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

s. A Christian

bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is an oral repository and professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's a ...

from the

Hebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

accompanied

Bjarni Herjolfsson on his voyage around

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

in 985/6 which sighted the mainland to the west.

[Michael Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'' (New York: Thomas Dunne, 2005), p. 7.]

The first Scots recorded as having set foot in the

New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

were a man named Haki and a woman named Hekja, slaves owned by

Leif Eiriksson. The Scottish couple were runners who scouted for

Thorfinn Karlsefni's expedition in c. 1010, gathering

wheat

Wheat is a group of wild and crop domestication, domesticated Poaceae, grasses of the genus ''Triticum'' (). They are Agriculture, cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known Taxonomy of wheat, whe ...

and the

grapes

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of grapes began approximately 8,0 ...

for which

Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland () was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. The name appears in the V ...

was named.

[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 8-9.]

The controversial

Zeno letters have been cited in support of a claim that

Henry Sinclair, earl of Orkney, visited

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

in 1398.

[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 10.]

In the early years of

Spanish colonization of the Americas

The Spanish colonization of the Americas began in 1493 on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) after the initial 1492 voyage of Genoa, Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus under license from Queen Isabella ...

, a Scot named Tam Blake spent 20 years in

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

and

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

. He took part in the conquest of

New Granada in 1532 with

Alonso de Heredia. He arrived in Mexico in 1534–5, and joined

Coronado Coronado may refer to:

People

* Coronado (surname) Coronado is a Spanish surname derived from the village of Cornado, near A Coruña, Galicia.

People with the name

* Francisco Vásquez de Coronado (1510–1554), Spanish explorer often referred t ...

's 1540 expedition to the

American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

.

[Jim Hewitson, ''Tam Blake & Co.: The Story of the Scots in America'' (Edinburgh: Orion, 1993), pp. 12-13.][Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 11.]

Traders

After the

Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns (; ) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas diplomacy) of the two separate realms under a single ...

of

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

and

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

in 1603,

King James VI, a Scot, promoted joint expeditions overseas, and became the founder of

British America

British America collectively refers to various British colonization of the Americas, colonies of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and its predecessors states in the Americas prior to the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War in 1 ...

.

[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 12.] The first permanent English settlement in the Americas,

Jamestown, was thus named for a Scot.

The earliest Scottish communities in America were formed by traders and

planters rather than farmer settlers.

[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 19.] The hub of Scottish commercial activity in the colonial period was

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. Regular contacts began with the

transportation

Transport (in British English) or transportation (in American English) is the intentional Motion, movement of humans, animals, and cargo, goods from one location to another. Mode of transport, Modes of transport include aviation, air, land tr ...

of

indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or ser ...

to the colony from Scotland, including prisoners taken in the

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities in a personal union un ...

.

[Alex Murdoch, "USA", Michael Lynch (ed), ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 629-633.]

By the 1670s

Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

was the main outlet for Virginian

tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

, in open defiance of English

restrictions on colonial trade; in return the colony received Scottish manufactured goods, emigrants and ideas.

[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 18, 19.] In the 1670s and 1680s Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

Dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

s fled persecution by the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

privy council in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

to settle in South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

and New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

, where they maintained their distinctive religious culture.[

Trade between Scotland and the American colonies was finally regularized by the ]Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union refer to two acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of Scotland in March 1707, followed shortly thereafter by an equivalent act of the Parliament of England. They put into effect the international Treaty of Union agree ...

that combined Scotland and England into the single kingdom of Great Britain. Population growth

Population growth is the increase in the number of people in a population or dispersed group. The World population, global population has grown from 1 billion in 1800 to 8.2 billion in 2025. Actual global human population growth amounts to aroun ...

and the commercialization of agriculture in Scotland encouraged mass emigration to America after the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

,[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 20.] a conflict which had also seen the first use of Scottish Highland regiments as Indian fighters.[

More than 50,000 Scots, principally from the west coast,][ settled in the ]Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

between 1763 and 1776, the majority of these in their own communities in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

,North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, although Scottish individuals and families also began to appear as professionals and artisans in every American town.[ Scots arriving in ]Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

and the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South or the South Coast, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The coastal states that have a shoreline on the Gulf of Mexico are Tex ...

traded extensively with Native Americans.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 41.]

Settlers

Highland Scots started arriving in North America in the 1730s. Unlike their Lowland and Ulster counterparts, the Highlanders tended to cluster together in self-contained communities, where they maintained their distinctive cultural features such as the Gaelic language and piobaireachd music. Groups of Highlanders existed in coastal Georgia (mainly immigrants from Inverness-shire) and the Mohawk Valley in New York (from the West Highlands). By far the largest Highland community was centered on the Cape Fear River

The Cape Fear River is a blackwater river in east-central North Carolina. It flows into the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Fear, from which it takes its name. The river is formed at the confluence of the Haw River and the Deep River in the town of ...

, which saw a stream of immigrants from Argyllshire, and, later, other regions such as the Isle of Skye

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye, is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated by the Cuillin, the rocky slopes of which provide some of ...

. Highland Scots were overwhelmingly loyalist in the Revolution. Distinctly Highland cultural traits persisted in the region until the 19th century, at which point they were assimilated into Anglo-American culture.

The Ulster Scots Ulster Scots, may refer to:

* Ulster Scots people

* Ulster Scots dialect

Ulster Scots or Ulster-Scots (), also known as Ulster Scotch and Ullans, is the dialect (whose proponents assert is a dialect of Scots language, Scots) spoken in parts ...

, known as the Scots-Irish (or Scotch-Irish) in North America, were descended from people originally from (mainly Lowland) Scotland, as well as the north of England and other regions, who colonized the province of Ulster in Ireland in the seventeenth century. After several generations, their descendants left for America, and struck out for the frontier, in particular the Appalachian mountains, providing an effective "buffer" for attacks from Native Americans. In the colonial era, they were usually simply referred to as "Irish," with the "Scots-" or "Scotch-" prefixes becoming popular when the descendants of the Ulster emigrants wanted to differentiate themselves from the Catholic Irish who were flocking to many American cities in the nineteenth century. Unlike the Highlanders and Lowlanders, the Scots-Irish were usually patriots in the Revolution. They have been noted for their tenacity and their cultural contributions to the United States.

Folk and gospel music

American bluegrass and country music

Country (also called country and western) is a popular music, music genre originating in the southern regions of the United States, both the American South and American southwest, the Southwest. First produced in the 1920s, country music is p ...

styles have some of their roots in the Appalachian ballad culture of Scotch-Irish Americans (predominantly originating from the "Border Ballad" tradition of southern Scotland and northern England). Fiddle tunes from the Scottish repertoire, as they developed in the eighteenth century, spread rapidly into British colonies. However, in many cases, this occurred through the medium of print rather than aurally, explaining the presence of Highland-origin tunes in regions like Appalachia where there was essentially no Highland settlement. Outside of Gaelic-speaking communities, however, characteristic Highland musical idioms, such as the “Scotch-snap,” were flattened out and assimilated into anglophone musical styles.

Some African American communities were influenced musically by the Scottish American communities in which they were embedded. Psalm-singing and gospel music have become central musical experiences for African American churchgoers and it has been posited that some elements of these styles were introduced, in these communities, by Scots. Psalm-singing, or " precenting the line" as it is technically known, in which the psalms are called out and the congregation sings a response, was a form of musical worship initially developed for non-literate congregations and Africans in America were exposed to this by Scottish Gaelic settlers as well as immigrants of other origins. However, the theory that the African-American practice was influenced mainly by the Gaels has been criticized by ethnomusicologist Terry Miller, who notes that the practice of "lining out

Lining out or hymn lining, called precenting the line in Scotland, is a form of ''a cappella'' hymn-singing or hymnody in which a leader, often called the clerk or precentor, gives each line of a hymn tune as it is to be sung, usually in a cha ...

" hymns and psalms was common all over Protestant Britain in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and that it is far more likely that Gospel music originated with English psalm singing.

The first foreign tongue spoken by some slaves in America was Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

picked up from Gaelic-speaking immigrants from the Scottish Highlands and Western Isles.

Patriots and Loyalists

The civic tradition of the Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment (, ) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century, Scotland had a network of parish schools in the Sco ...

contributed to the intellectual ferment of the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

.[ In 1740, the Glasgow philosopher Francis Hutcheson argued for a right of colonial resistance to tyranny.][Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 28-29.] Scotland's leading thinkers of the revolutionary age, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, opposed the use of force against the rebellious colonies.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 29-32.] According to the historian Arthur L. Herman: "Americans built their world around the principles of Adam Smith and Thomas Reid

Thomas Reid (; 7 May (Julian calendar, O.S. 26 April) 1710 – 7 October 1796) was a religiously trained Scotland, Scottish philosophy, philosopher best known for his philosophical method, his #Thomas_Reid's_theory_of_common_sense, theory of ...

, of individual interest governed by common sense and a limited need for government."[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 154.]

John Witherspoon and James Wilson were the two Scots to sign the Declaration of Independence, and several other signers had ancestors there. Other Founding Father

The following is a list of national founders of sovereign states who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e., political system ...

like James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

had no ancestral connection but were imbued with ideas drawn from Scottish moral philosophy.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 38-40.] Scottish Americans who made major contributions to the revolutionary war included Commodore John Paul Jones

John Paul Jones (born John Paul; July 6, 1747 – July 18, 1792) was a Scottish-born naval officer who served in the Continental Navy during the American Revolutionary War. Often referred to as the "Father of the American Navy", Jones is regard ...

, the "Father of the American Navy", and Generals Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806) was an American military officer, politician, bookseller, and a Founding Father of the United States. Knox, born in Boston, became a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionar ...

and William Alexander. Another person of note was a personal friend of George Washington, General Hugh Mercer

Hugh Mercer (January 16, 1726 – January 12, 1777) was a Scottish brigadier general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He fought in the New York and New Jersey campaign and was mortally wounded at the Battle of Pri ...

, who fought for Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart (31 December 1720 – 30 January 1788) was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart, making him the grandson of James VII and II, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, ...

at the Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Culloden took place on 16 April 1746, near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands. A Jacobite army under Charles Edward Stuart was decisively defeated by a British government force commanded by the Duke of Cumberland, thereby endi ...

.

The Scotch-Irish, who had already begun to settle beyond the Proclamation Line in the Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

and Tennessee Valley

The Tennessee Valley is the drainage basin of the Tennessee River and is largely within the U.S. state of Tennessee. It stretches from southwest Kentucky to north Alabama and from northeast Mississippi to the mountains of Virginia and North C ...

s, were drawn into rebellion as war spread to the frontier.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 13, 23.] Tobacco plantations and independent farms in the backcountry of Virginia, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

and the Carolinas

The Carolinas, also known simply as Carolina, are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the southwes ...

had been financed with Scottish credit, and indebtedness was an additional incentive for separation.clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

allegiances and stayed true to the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 13, 24-26.] The Scottish Highland communities of upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region of New York (state), New York that lies north and northwest of the New York metropolitan area, New York City metropolitan area of downstate New York. Upstate includes the middle and upper Hudson Valley, ...

and the Cape Fear valley of North Carolina were centers of Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

resistance.[ A small force of Loyalist Highlanders fell at the ]Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge

The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge was a minor conflict of the American Revolutionary War fought near Wilmington, North Carolina, Wilmington (present-day Pender County, North Carolina, Pender County), North Carolina, on February 27, 1776. The v ...

in 1776. Scotch-Irish Patriots

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

defeated Scottish American Loyalists in the Battle of Kings Mountain in 1780.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 28.] Many Scottish American Loyalists, particularly Highlanders, emigrated to Canada after the war.[

]

Uncle Sam

Uncle Sam

Uncle Sam (with the same initials as ''United States'') is a common national personification of the United States, depicting the federal government of the United States, federal government or the country as a whole. Since the early 19th centu ...

is the national personification

A national personification is an anthropomorphic personification of a state or the people(s) it inhabits. It may appear in political cartoons and propaganda. In the first personifications in the Western World, warrior deities or figures symboliz ...

of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, and sometimes more specifically of the American government, with the first usage of the term dating from the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

.

The American icon Uncle Sam, who is known for embodying the American spirit, was based on a businessman from Troy, New York

Troy is a city in and the county seat of Rensselaer County, New York, United States. It is located on the western edge of the county, on the eastern bank of the Hudson River just northeast of the capital city of Albany, New York, Albany. At the ...

, Samuel Wilson, whose parents sailed to America from Greenock

Greenock (; ; , ) is a town in Inverclyde, Scotland, located in the west central Lowlands of Scotland. The town is the administrative centre of Inverclyde Council. It is a former burgh within the historic county of Renfrewshire, and forms ...

, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, has been officially recognized as the original Uncle Sam. He provided the army with beef and pork in barrels during the War of 1812. The barrels were prominently labeled "U.S." for the United States, but it was jokingly said that the letters stood for "Uncle Sam." Soon, Uncle Sam was used as shorthand for the federal government.

Emigrants and free traders

Trade with Scotland continued to flourish after U.S. independence. The tobacco trade was overtaken in the nineteenth century by the cotton

Cotton (), first recorded in ancient India, is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure ...

trade, with Glasgow factories exporting the finished textiles back to the United States on an industrial scale.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 19, 41.]

Emigration from Scotland peaked in the nineteenth century, when more than a million Scots left for the United States,[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 193.] taking advantage of the regular Atlantic steam-age shipping industry which was itself largely a Scottish creation,[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 194.] contributing to a revolution in transatlantic communication.[

Scottish emigration to the United States followed, to a lesser extent, during the twentieth century, when Scottish heavy industry declined.][Evans, Nicholas J., 'The Emigration of Skilled Male Workers from Clydeside during the Interwar Period', ''International Journal of Maritime History'', Volume XVIII, Number 1 (2006), pp. 255-280.] This new wave peaked in the first decade of the twentieth century, contributing to a hard life for many who remained behind. Many qualified workers emigrated overseas, a part of which, established in Canada, later went on to the United States.[Everyculture:Scottish American]

Posted by Mary A. Hess. Retrieved January 3, 2012, to 1:25 pm.

Writers

In the nineteenth century, American authors and educators adopted Scotland as a model for cultural independence.[ In the world of letters, Scottish literary icons James Macpherson, ]Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

, Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

, and Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

had a mass following in the United States, and Scottish Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

exerted a seminal influence on the development of American literature.[ The works of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne bear its powerful impression. Among the most notable Scottish American writers of the nineteenth century were Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, Edgar Allan Poe and Herman Melville. Poet James Mackintosh Kennedy was called to Scotland to deliver the official poem for the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn in 1914.

In the twentieth century, Margaret Mitchell's ''Gone with the Wind (novel), Gone With the Wind'' exemplified popular literature. William Faulkner won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949.

There have been a number of notable ]Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

poets active in the United States since the eighteenth century, including Aonghas MacAoidh and Domhnall Aonghas Stiùbhart. One of the few relics of Gaelic literature composed in the United States is a lullaby composed by an anonymous woman in the Carolinas during the American Revolutionary War. It remains popular to this day in Scotland.

Soldiers and statesmen

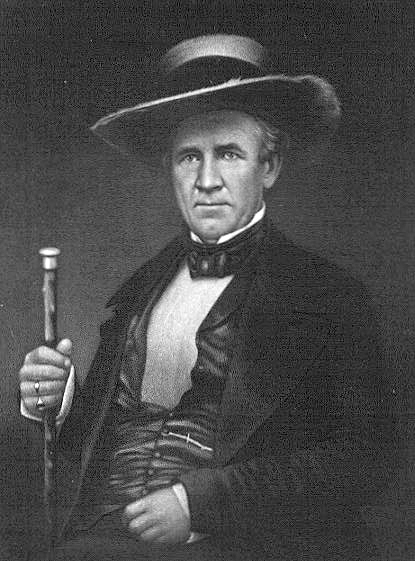

More than 160,000 Scottish emigrants migrated to the U.S., American statesmen of Scottish descent in the early Republic included United States Secretary of the Treasury, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, United States Secretary of War, Secretary of War Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806) was an American military officer, politician, bookseller, and a Founding Father of the United States. Knox, born in Boston, became a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionar ...

, and President of the United States, President James Monroe. Andrew Jackson and James K. Polk were Scotch-Irish presidents and products of the frontier in the period of History of the United States (1789–1849)#Westward expansion, Westward expansion. Among the most famous Scottish American soldier frontiersmen was Sam Houston, founding father of Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

.

Other Scotch-Irish presidents included James Buchanan, Chester Alan Arthur, William McKinley and Richard M. Nixon, Theodore Roosevelt (through his mother), Woodrow Wilson, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Ronald Reagan were of Scottish descent.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 53.] By one estimate, 75% of U.S. presidents could claim some Scottish ancestry.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 60-61.]

Scottish Americans fought on both sides of the American Civil War, Civil War, and a monument to their memory was erected in

Scottish Americans fought on both sides of the American Civil War, Civil War, and a monument to their memory was erected in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, Scotland, in 1893. Winfield Scott, Ulysses S. Grant, Joseph E. Johnston, Irvin McDowell, James B. McPherson, Jeb Stuart and John B. Gordon were of Scottish descent, George B. McClellan and Stonewall Jackson Scotch-Irish.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 53, 72.]

Douglas MacArthur and George Marshall upheld the martial tradition in the twentieth century. Grace Murray Hopper, a rear admiral and computer scientist, was the oldest officer and highest-ranking woman in the U.S. armed forces on her retirement at the age of 80 in 1986.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 219-220.] Isabella Cannon, the former Raleigh, North Carolina, Mayor of Raleigh, North Carolina, served as the first female mayor of a U.S. state capital.

Automakers

The Scottish-born Alexander Winton built one of the first American automobiles in 1896, and specialized in motor racing. He broke the world speed record in 1900.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', p. 221.] In 1903, he became the first man to drive across the United States.[ David Dunbar Buick, another Scottish emigrant, founded Buick in 1903.][ The Scottish-born William Blackie transformed the Caterpillar Inc., Caterpillar Tractor Company into a multinational corporation.][

]

Motorcycle manufacturer

Harley-Davidson Inc

Harley-Davidson Inc

Aviation

Scottish Americans have made a major contribution to the U.S. aircraft industry. Alexander Graham Bell, in partnership with Samuel Pierpont Langley, built the first machine capable of flight, the Aviation history#Langley, Bell-Langley airplane, in 1903.[Fry, ''How the Scots Made America'', pp. 221-223.] Lockheed Corporation, Lockheed was started by two brothers, Allan Loughead, Allan and Malcolm Loughead, in 1926.[ Douglas Aircraft Company, Douglas was founded by Donald Wills Douglas Sr. in 1921; he launched the world's first commercial passenger plane, the DC-3, in 1935.][ McDonnell Aircraft was founded by James Smith McDonnell, in 1939, and became famous for its military Jet aircraft, jets.][ In 1967, McDonnell and Douglas McDonnell Douglas, merged and jointly developed jet aircraft, missiles and spacecraft.][

]

Spaceflight

Scottish Americans were pioneers in human spaceflight. The Project Mercury, Mercury and Project Gemini, Gemini capsules were built by McDonnell.[ The first American in space, Alan Shepard, the first American in orbit, John Glenn, and the first man to fly free in space, Bruce McCandless II, were Scottish Americans.][

The first men on the Moon, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, were also of Scottish descent; Armstrong wore a kilt in a parade through his ancestral home of Langholm in the Scottish Borders in 1972.][ Armstrong's ancestry can be traced back to his eighth paternal great-grandfather Adam Armstrong from the Scottish Borders. His son Adam II and grandson Adam Abraham (b. Cumberland, England) left for the colonies in the 1730s settling in Pennsylvania.

Other Scottish American moonwalkers were the fourth, Alan Bean, the fifth, Alan Shepard, the seventh, David Scott (also the first to drive on the Moon), and the eighth, James Irwin.][

]

Computing

Scottish Americans Howard Aiken and Grace Murray Hopper created the first automatic sequence computer in 1939.[ Hopper was also the co-inventor of the computer language COBOL.][

Ross Perot, another Scottish American entrepreneur, made his fortune from Electronic Data Systems, an outsourcing company he established in 1962.][

Software giant Microsoft was co-founded in 1975 by Bill Gates, who owed his start in part to his mother, the Scottish American businesswoman Mary Maxwell Gates, who helped her son to get his first software contract with IBM.][ Glasgow-born Microsoft employee Richard Tait helped develop the ''Encarta'' encyclopedia and co-created the popular board game Cranium (board game), Cranium.][

]

Cuisine

Scottish Americans have helped to define the modern American diet by introducing many distinctive foods.

Philip Danforth Armour founded Armour and Company, Armour Meats in 1867, revolutionizing the American meatpacking industry and becoming famous for hot dogs. Campbell Soups was founded in 1869 by Joseph A. Campbell and rapidly grew into a major manufacturer of canned soups. Will Keith Kellogg, W. K. Kellogg transformed American eating habits from 1906 by popularizing breakfast cereal. Glen Bell, founder of Taco Bell in 1962, introduced Tex-Mex food to a mainstream audience. Marketing executive Arch West, born to Scottish emigrant parents, developed Doritos.

Community activities

Some of the following aspects of Scottish culture can still be found in some parts of the United States.

* Bagpipes, Bagpiping and pipe bands

* Burns Supper

Tartan Day

Tartan Day, National Tartan Day, held each year on April 6 in the

Tartan Day, National Tartan Day, held each year on April 6 in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, celebrates the historical links between Scotland and North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

and the contributions Scottish Americans and Canadians have made to U.S. and Canadian democracy, industry and society. The date of April 6 was chosen as "the anniversary of the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320—the inspirational document, according to U.S. Senate Resolution 155, 1999, upon which the American Declaration of Independence was modeled".[Edward J. Cowan, "Tartan Day in America", in Celeste Ray (ed.), ''The Transatlantic Scots'' (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2005), p. 318.]

The Annual Tartan Week celebrations come to life every April with the largest celebration taking place in New York City. Thousands descend onto the streets of the Big Apple to celebrate their heritage, culture and the impact of the Scottish people, Scottish Americans in America today.

Hundreds of pipers, drummers, Highland dancers, Scottie Dogs and celebrities march down the streets drowned in their family tartans and Saltire flags whilst interacting with the thousands of onlookers.

Scottish Heritage Month is also promoted by community groups around the United States and Canada.[National Scots, Scots-Irish Heritage Month in the USA](_blank)

ElectricScotland.com

Scottish Festivals

Scottish culture, food, and athletics are celebrated at Highland Games and Scottish festivals throughout North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

. The largest of these occurs yearly at Pleasanton, California, Grandfather Mountain, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

and Estes Park, Colorado. There are also other notable Scottish Festivals in cities like Tulsa, Oklahoma, Ventura, California at the Seaside Highland Games, Atlanta, Georgia (at Stone Mountain Park), San Antonio, Texas and St. Louis, Missouri. In addition to traditional Scottish sports such as caber toss, tossing the caber and the hammer throw, there are whisky tastings, traditional foods such as haggis, Bagpipes and Drums competitions, Celtic rock musical acts and traditional Scottish dance.

Scottish Gaelic language in the United States

Although Scottish Gaelic language, Scottish Gaelic had been spoken in most of Scotland at one time or another, by the time of large-scale migrations to North America – the eighteenth century – it had only managed to survive in the Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland. Unlike other ethnic groups in Scotland, Scottish Highlanders preferred to migrate in communities, and remaining in larger, denser concentrations aided in the maintenance of their language and culture. The first communities of Scottish Gaels began migrating in the 1730s to Georgia, New York and the Carolinas. Only in the Carolinas were these settlements enduring. Although their numbers were small, the immigrants formed a beach-head for later migrations, which accelerated in the 1760s.

The American Revolutionary War effectively stopped direct migration to the newly formed United States, most people going instead to British North America (now Canada). The Canadian Maritimes were a favored destination from the 1770s to the 1840s. Sizable concentrations of Gaelic communities existed in Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island, with smaller clusters in Newfoundland, Quebec, and New Brunswick. Those who left these communities for opportunities in the United States, especially in New England, were usually fluent Gaelic speakers into the mid-twentieth century.

Of the many communities founded by Scottish Highland immigrants, the language and culture only survives at a community level in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

. According to the 2000 census, 1,199 people speak Scottish Gaelic at home.

The direct descendants of Scottish Highlanders were not the only people in the United States to speak the language, however. Gaelic was one of the languages spoken by fur traders in many parts of North America. In some parts of the Carolinas and Alabama, African-American communities spoke Scottish Gaelic, particularly (but not solely) due to the influence of Gaelic-speaking slave-owners.

Notable people

Presidents of Scottish or Scotch-Irish descent

Several President of the United States, presidents of the United States have had some Scottish or Scotch-Irish ancestry, although the extent of this varies. For example, Donald Trump's mother was Scottish and Woodrow Wilson's maternal grandparents were both Scottish. Ronald Reagan, Gerald Ford, Chester A. Arthur and William McKinley have less direct Scottish or Scotch-Irish ancestry.

;James Monroe (Scottish and Welsh)

: 5th President, 1817-1825: His paternal great-great-grandfather, Andrew Monroe, emigrated to America from Ross-shire, Scotland in the mid-17th century.

;Andrew Jackson (Scotch-Irish)

: 7th President, 1829-1837: : He was born in the predominantly Ulster-Scots Waxhaws area of South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

two years after his parents left Boneybefore, near Carrickfergus in County Antrim.North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

.[Northern Ireland Tourist Board]

''discovernorthernireland - explore more: Arthur Cottage''

Accessed 03/03/2010. "Arthur Cottage, situated in the heart of County Antrim, only a short walk from the village of Cullybackey is the ancestral home of Chester Alan Arthur, the 21st President of the USA."

;Grover Cleveland (Scotch-Irish and English)

:22nd and 24th President, 1885-1889 and 1893-1897: Born in New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

, he was the maternal grandson of merchant Abner Neal, who emigrated from County Antrim in the 1790s. He was the first president to have served non-consecutive terms.

Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

.

Vice Presidents of Scottish or Scotch-Irish descent

;John C. Calhoun (Scotch-Irish)

:10th Vice President, 1825-1832

;George M. Dallas (Scottish)

:15th Vice President, 1845-1849; former Secretary of War

;Adlai Stevenson I (Scottish and Scotch-Irish)

:23rd Vice President, 1893-1897: The Stevensons (Stephensons) are first recorded in Roxburghshire in the 18th century.

;Charles Curtis (Scottish)

Other American presidents of Scottish or Scotch-Irish descent

;Sam Houston (Scotch-Irish)

:President of Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, 1836-1838 and 1841-1844 [

;Jefferson Davis (Scotch-Irish)

:President of Confederate States of America, 1861-1865

;Arthur St. Clair (Scottish)

:President under the List of Presidents of the Congress under the Articles of Confederation, Articles of Confederation, 1788

]

Scottish placenames

Some place names of Scottish origin (either named after Scottish places or Scottish immigrants) in the U.S. include:

*California

**Albion, California, Albion

**Ben Lomond, California, Ben Lomond

**Bonny Doon, California, Bonny Doon

**Inverness, California, Inverness

**Irvine, California, Irvine, named for the historic Irvine Ranch, and Irvine Subdivision of Orange County, California

*Colorado

**Montrose, Colorado, Montrose

*Connecticut

**Scotland, Connecticut, Scotland

*Delaware

**Glasgow, Delaware, Glasgow

**Perth, Delaware, Perth

*Florida

**Paisley, Florida, Paisley

**Dundee, Florida, Dundee

**Dunedin, Florida, Dunedin, from ''Dùn Èideann'', Scottish Gaelic for Edinburgh

**Inverness, Florida, Inverness

*Illinois

**Dundee, Illinois, Dundee

**Elgin, Illinois, Elgin

**Inverness, Illinois, Inverness

**Midlothian, Illinois, Midlothian

**Bannockburn, Illinois, Bannockburn

**Glencoe, Illinois, Glencoe

*Indiana

**Perth, Indiana, Perth

**Edinburgh, Indiana, Edinburgh

*Kansas

**Dundee, Kansas, Dundee

*Kentucky

**Glasgow, Kentucky, Glasgow

*Louisiana

**Gretna, Louisiana, Gretna

**Scotlandville, Louisiana, Scotlandville

*Maine

**Argyle, Maine, Argyle

* Maryland

**Aberdeen, Maryland, Aberdeen

**Glencoe, Maryland, Glencoe

**Glenelg, Maryland, Glenelg

**Lochearn, Maryland, Lochearn

**Lothian, Maryland, Lothian

**Midlothian, Maryland, Midlothian

**Muirkirk, Maryland, Muirkirk

* Massachusetts

**Melrose, Massachusetts, Melrose

*Mississippi

**Aberdeen, Mississippi, Aberdeen

* Montana

**Glasgow, Montana, Glasgow

**Aberdeen, Montana

**Inverness, Montana

**Drummond, Montana

* New Jersey

**Aberdeen

**Perth Amboy, New Jersey, Perth Amboy

**Scotch Plains, New Jersey, Scotch Plains

*New York

**Albany, New York, Albany

**Argyle

**Dundee, New York, Dundee

**Perth, New York, Perth

*North Carolina

**Aberdeen, North Carolina, Aberdeen

**Clyde, North Carolina, Clyde

**Cumnock, North Carolina, Cumnock

**Dundarrach, North Carolina, Dundarrach

**Glencoe, North Carolina, Glencoe

**Highlands, North Carolina, Highlands

**Inverness

**Roxboro, North Carolina, Roxboro - a variant spelling of Roxburgh

**Scotland County, North Carolina, Scotland County

*North Dakota

**Perth, North Dakota, Perth

**Perth Township, Walsh County, North Dakota, Perth Township

*Oklahoma

**Glencoe, Oklahoma, Glencoe

**Guthrie, Oklahoma, Guthrie

*Oregon

**Albany, Oregon, Albany

**Burns, Oregon, Burns - after Scottish poet Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

**Dundee, Oregon, Dundee

**Elgin, Oregon, Elgin

**Glencoe, Oregon, Glencoe

**Hermiston, Oregon, Hermiston

**Macleay, Oregon, Macleay

**McDonald, Oregon, McDonald

**McEwen, Oregon, McEwen

**Melrose, Oregon, Melrose

**Nibley, Oregon, Nibley

**Sutherlin, Oregon, Sutherlin - a variant spelling of Sutherland

**Paisley, Oregon, Paisley

**Wedderburn, Oregon, Wedderburn

*Pennsylvania

**Edinboro, Pennsylvania, Edinboro - a variant spelling of Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

**Glasgow, Beaver County, Pennsylvania, Glasgow

**Scotland, Pennsylvania, Scotland - Franklin County town, fictional site of the motion picture Scotland, PA

*South Carolina

**Elgin, Kershaw County, South Carolina, Elgin

**Lake Murray (South Carolina), Lake Murray

*Texas

**Argyle, Texas, Argyle - a variant spelling of Argyll

**Dallas, Texas, Dallas

**Edinburg, Texas, Edinburg - a variant spelling of Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

**Houston, Texas, Houston - suburbs include Neartown Houston, Montrose

**Midlothian, Texas, Midlothian

**Scotland, Texas, Scotland

*Utah

**Argyle, Utah, Argyle (now a ghost town)

**Ben Lomond Mountain (Utah), Ben Lomond

**Logan, Utah, Logan

*Virginia

**Dumfries, Virginia, Dumfries

**Glasgow, Virginia, Glasgow

**Gretna, Virginia, Gretna

**Hamilton, Loudoun County, Virginia, Hamilton

**Kilmarnock, Virginia, Kilmarnock

**McDowell, Virginia, McDowell

**Midlothian, Virginia, Midlothian

* Washington state

**Aberdeen, Washington, Aberdeen

**Fife, Washington, Fife

* Wisconsin

** Argyle, Wisconsin, Argyle

** Dunbar, Wisconsin, Dunbar

See also

*Scottish diaspora

*Americans

**British American

**Cornish Americans

**English American

**Irish American

**Scotch-Irish American

**Welsh American

*Celtic music in the United States

*Scots by country

**Scots-Quebecer

**Scottish Canadian

**Scottish Australian

**Scottish New Zealanders

**Scottish Brazilians

**Scottish Argentine

Notes

References

Further reading

* Bell, Whitfield J. “Scottish Emigration to America: A Letter of Dr. Charles Nisbet to Dr. John Witherspoon, 1784.” ''William and Mary Quarterly'' 11#2 1954, pp. 276–289

online

a primary source

* Berthoff, Rowland Tappan. ''British Immigrants in Industrial America, 1790-1950.'' (Harvard University Press, 1953).

* Bumsted, Jack M. "The Scottish Diaspora: Emigration to British North America, 1763–1815." in Ned C. Landsman, ed., ''Nation and Province in the First British Empire: Scotland and the Americas, 1600–1800'' (2001) pp 127–5

online

* Bueltmann, Tanja, Andrew Hinson, and Graeme Morton. ''The Scottish Diaspora.'' Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press, 2013.

* Calder, Jenni. ''Lost in the Backwoods: Scots and the North American Wilderness'' Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press, 2013.

* Calder, Jenni. ''Scots in the USA.'' Luath Press Ltd, 2014.

* Dobson, David. ''Scottish emigration to colonial America, 1607-1785.'' Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

* Dziennik, Matthew P. ''The Fatal Land: War, Empire, and the Highland Soldier in British America.'' (Yale University Press, 2015).

* Erickson, Charlotte. ''Invisible Immigrants: the Adaptation of English and Scottish Immigrants in 19th Century America'' (Weidenfeld and Nicolson; 1972)

* Hess, Mary A. "Scottish Americans." in ''Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America,'' edited by Thomas Riggs, *3rd ed., vol. 4, Gale, 2014), pp. 101–112

Online

* Hunter, James. ''Scottish exodus: travels among a worldwide clan'' (Random House, 2011); interviews with Clan MacLeod members

* Landsman, Ned C. ''Scotland and Its First American Colony, 1683-1765.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014.

* McCarthy, James, and Euan Hague. "Race, nation, and nature: The cultural politics of 'Celtic' identification in the American West." ''Annals of the Association of American Geographers'' 94#2 (2004): 387–408.

* McWhiney, Grady, and Forrest McDonald. "Celtic origins of southern herding practices." ''Journal of Southern History'' (1985): 165–182

in JSTOR

* Newton, Michael. ''“We’re Indians Sure Enough”: The Legacy of the Scottish Highlanders in the United States.'' Richmond: Saorsa Media, 2001.

* Parker, Anthony W. ''Scottish Highlanders in Colonial Georgia: The Recruitment, Emigration, and Settlement at Darien, 1735-1748.'' Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2002.

* Ray, R. Celeste. ''Highland Heritage: Scottish Americans in the American South.'' Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

* Szasz, Ferenc Morton. ''Scots in the North American West, 1790-1917.'' Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000.

* Thernstrom, Stephan, ed. ''Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups.'' New Haven, CT: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Historiography

* Berthoff, Rowland. "Under the kilt: Variations on the Scottish-American ground." ''Journal of American Ethnic History'' 1#2 (1982): 5-34

in JSTOR

* Berthoff, Rowland. "Celtic mist over the South." ''Journal of Southern History'' (1986) pp: 523–546

in JSTOR

Highly critical of theories of Forrest McDonald and Grady McWhiney regarding profound Celtic influences

** McDonald, Forrest, and Grady McWhiney. "Celtic Mist over the South: A Response." ''Journal of Southern History'' (1986): 547–548.

* Shepperson, George. “Writings in Scottish-American History: A Brief Survey.” ''William and Mary Quarterly'' 11#2 1954, pp. 164–178

online

* Zumkhawala-Cook, Richard. "The Mark of Scottish America: Heritage Identity and the Tartan Monster." ''Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies'' 14#1 (2005) pp: 109–136.

External links

*

Scottish Emigration DatabaseScotlands People - Official government source for Scottish rootsUS Scots: includes extensive listing of Highland games eventsWebsite of ''An Comunn Gàidhealach Ameireaganach''

{{Demographics of the United States

American people of Scottish descent, *

British-American history, Scottish

British diaspora in the United States

Scottish-American history, Scottish

After the

After the

Scottish Americans fought on both sides of the American Civil War, Civil War, and a monument to their memory was erected in

Scottish Americans fought on both sides of the American Civil War, Civil War, and a monument to their memory was erected in  Harley-Davidson Inc (formerly HDI), often abbreviated "H-D" or "Harley", is an American motorcycle manufacturer. The Davidson brothers were the sons of William C Davidson (1846–1923) who was born and grew up in Angus, Scotland, and Margaret Adams McFarlane (1843–1933) of Scottish descent from the small Scottish settlement of Cambridge, Wisconsin. They raised five children together: Janet May, William A., Arthur Davidson (motorcycling), Walter, Arthur and Elizabeth.

Harley-Davidson Inc (formerly HDI), often abbreviated "H-D" or "Harley", is an American motorcycle manufacturer. The Davidson brothers were the sons of William C Davidson (1846–1923) who was born and grew up in Angus, Scotland, and Margaret Adams McFarlane (1843–1933) of Scottish descent from the small Scottish settlement of Cambridge, Wisconsin. They raised five children together: Janet May, William A., Arthur Davidson (motorcycling), Walter, Arthur and Elizabeth.

Tartan Day, National Tartan Day, held each year on April 6 in the

Tartan Day, National Tartan Day, held each year on April 6 in the