Sassafras albidum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Sassafras albidum'' (sassafras, white sassafras, red sassafras, or silky sassafras) is a species of ''

''Sassafras albidum''

/ref>U.S. Forest Service

''Sassafras albidum'' (pdf file)

/ref>Hope College, Michigan

/ref> It formerly also occurred in southern

All parts of the ''Sassafras albidum'' plant have been used for human purposes, including stems, leaves, bark, wood, roots, fruit, and flowers. ''Sassafras albidum'', while native to North America, is significant to the economic, medical, and cultural history of both Europe and North America. In North America, it has particular culinary significance, being featured in distinct national foods such as traditional

All parts of the ''Sassafras albidum'' plant have been used for human purposes, including stems, leaves, bark, wood, roots, fruit, and flowers. ''Sassafras albidum'', while native to North America, is significant to the economic, medical, and cultural history of both Europe and North America. In North America, it has particular culinary significance, being featured in distinct national foods such as traditional

''Sassafras albidum'' was a well-used plant by Native Americans in what is now the

''Sassafras albidum'' was a well-used plant by Native Americans in what is now the

''Sassafras albidum'' is used primarily in the United States as the key ingredient in home brewed root beer and as a thickener and flavouring in traditional

''Sassafras albidum'' is used primarily in the United States as the key ingredient in home brewed root beer and as a thickener and flavouring in traditional

Safrole can be obtained fairly easily from the root bark of ''Sassafras albidum'' via steam distillation. It has been used as a natural insect or pest deterrent. Godfrey's Cordial, as well as other tonics given to children that consisted of

Safrole can be obtained fairly easily from the root bark of ''Sassafras albidum'' via steam distillation. It has been used as a natural insect or pest deterrent. Godfrey's Cordial, as well as other tonics given to children that consisted of  Commercial "sassafras oil," which contains safrole, is generally a byproduct of

Commercial "sassafras oil," which contains safrole, is generally a byproduct of

''Sassafras albidum''

/ref>

Summary of his life and expeditions at American Journeys website, 2012, Wisconsin Historical Society Since the bark was the most commercially valued part of the sassafras plant due to large concentrations of the aromatic safrole oil, commercially valuable sassafras could only be gathered from each tree once. This meant that as significant amounts of sassafras bark were gathered, supplies quickly diminished and sassafras become more difficult to find. For example, while one of the earliest shipments of sassafras in 1602 weighed as much as a ton, by 1626, English colonists failed to meet their 30-pound quota. The gathering of sassafras bark brought European settlers and Native Americans into contact sometimes dangerous to both groups. Sassafras was such a desired commodity in England, that its importation was included in the Charter of the Colony of Virginia in 1610. Through modern times the sassafras plant, both wild and cultivated, has been harvested for the extraction of safrole, which is used in a variety of commercial products as well as in the manufacture of illegal drugs like MDMA; yet, sassafras plants in China and Brazil are more commonly used for these purposes than North American ''Sassafras albidum''.

File:Sassafras1979.jpg, Unilobed leaf

File:Sassafras1592.jpg, Bilobed leaf

File:Sassafras Sassafras albidum Leaf 2505px.jpg, Trilobed leaf

File:Sassafras9810.JPG, Flowers

File:Sassafras Flowers 4-24-2014.JPG, Flowers

File:Sassafras albidum Trunk Bark 3264px.jpg, Bark

File:Sassafras albidum seed.JPG, The fruit

File:SassafrasAutumncloseup.JPG, Autumn foliage closeup

File:Sassafras, Saxifras, Tea Tree, Mitten Tree, Cinnamonwood (Sassafras albidum) sapling.jpg, Seedling

Sassafras

''Sassafras'' is a genus of three extant and one extinct species of deciduous trees in the family Lauraceae, native to eastern North America and eastern Asia.Wolfe, Jack A. & Wehr, Wesley C. 1987. The sassafras is an ornamental tree. "Middle E ...

'' native to eastern North America, from southern Maine

Maine () is a U.S. state, state in the New England and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and territories of Canad ...

and southern Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

west to Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

, and south to central Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, a ...

and eastern Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

. It occurs throughout the eastern deciduous forest

In the fields of horticulture and Botany, the term ''deciduous'' () means "falling off at maturity" and "tending to fall off", in reference to trees and shrubs that seasonally shed leaves, usually in the autumn; to the shedding of petals, af ...

habitat type, at altitudes of up to above sea level.Flora of North America''Sassafras albidum''

/ref>U.S. Forest Service

''Sassafras albidum'' (pdf file)

/ref>Hope College, Michigan

/ref> It formerly also occurred in southern

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, but is extirpated there as a native tree.

Description

''Sassafras albidum'' is a medium-sizeddeciduous

In the fields of horticulture and Botany, the term ''deciduous'' () means "falling off at maturity" and "tending to fall off", in reference to trees and shrubs that seasonally shed leaves, usually in the autumn; to the shedding of petals, a ...

tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, including only woody plants with secondary growth, plants that are ...

growing to tall, with a canopy up to wide, with a trunk up to in diameter, and a crown with many slender sympodial

Sympodial growth is a bifurcating branching pattern where one branch develops more strongly than the other, resulting in the stronger branches forming the primary shoot and the weaker branches appearing laterally. A sympodium, also referred to a ...

branches. The bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, ...

on trunk of mature trees is thick, dark red-brown, and deeply furrowed. The shoots are bright yellow green at first with mucilaginous

Mucilage is a thick, gluey substance produced by nearly all plants and some microorganisms. These microorganisms include protists which use it for their locomotion. The direction of their movement is always opposite to that of the secretion of ...

bark, turning reddish brown, and in two or three years begin to show shallow fissures. The leaves are alternate, green to yellow-green, ovate or obovate, long and broad with a short, slender, slightly grooved petiole. They come in three different shapes, all of which can be on the same branch; three-lobed leaves, unlobed elliptical leaves, and two-lobed leaves; rarely, there can be more than three lobes. In fall, they turn to shades of yellow, tinged with red. The flower

A flower, sometimes known as a bloom or blossom, is the reproductive structure found in flowering plants (plants of the division Angiospermae). The biological function of a flower is to facilitate reproduction, usually by providing a mechanism ...

s are produced in loose, drooping, few-flowered raceme

A raceme ( or ) or racemoid is an unbranched, indeterminate type of inflorescence bearing flowers having short floral stalks along the shoots that bear the flowers. The oldest flowers grow close to the base and new flowers are produced as the sh ...

s up to long in early spring shortly before the leaves appear; they are yellow to greenish-yellow, with five or six tepal

A tepal is one of the outer parts of a flower (collectively the perianth). The term is used when these parts cannot easily be classified as either sepals or petals. This may be because the parts of the perianth are undifferentiated (i.e. of very ...

s. It is usually dioecious

Dioecy (; ; adj. dioecious , ) is a characteristic of a species, meaning that it has distinct individual organisms (unisexual) that produce male or female gametes, either directly (in animals) or indirectly (in seed plants). Dioecious reproducti ...

, with male and female flowers on separate trees; male flowers have nine stamens

The stamen (plural ''stamina'' or ''stamens'') is the pollen-producing reproductive organ of a flower. Collectively the stamens form the androecium., p. 10

Morphology and terminology

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filam ...

, female flowers with six staminodes (aborted stamens) and a 2–3 mm style on a superior ovary. Pollination

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther of a plant to the stigma of a plant, later enabling fertilisation and the production of seeds, most often by an animal or by wind. Pollinating agents can be animals such as insects, birds ...

is by insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s. The fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in partic ...

is a dark blue-black drupe

In botany, a drupe (or stone fruit) is an indehiscent fruit in which an outer fleshy part ( exocarp, or skin, and mesocarp, or flesh) surrounds a single shell (the ''pit'', ''stone'', or '' pyrena'') of hardened endocarp with a seed (''kerne ...

long containing a single seed

A seed is an embryonic plant enclosed in a protective outer covering, along with a food reserve. The formation of the seed is a part of the process of reproduction in seed plants, the spermatophytes, including the gymnosperm and angiosper ...

, borne on a red fleshy club-shaped pedicel long; it is ripe in late summer, with the seeds dispersed by bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s. The cotyledon

A cotyledon (; ; ; , gen. (), ) is a significant part of the embryo within the seed of a plant, and is defined as "the embryonic leaf in seed-bearing plants, one or more of which are the first to appear from a germinating seed." The num ...

s are thick and fleshy. All parts of the plant are aromatic and spicy. The root

In vascular plants, the roots are the organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often below the sur ...

s are thick and fleshy, and frequently produce root sprouts which can develop into new trees.

Ecology

It prefers rich, well-drained sandyloam

Loam (in geology and soil science) is soil composed mostly of sand ( particle size > ), silt (particle size > ), and a smaller amount of clay (particle size < ). By weight, its mineral composition is about 40–40–20% concentration of sand–si ...

with a pH of 6–7, but will grow in any loose, moist soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former ...

. Seedlings will tolerate shade, but saplings and older trees demand full sunlight for good growth; in forests it typically regenerates in gaps created by windblow. Growth is rapid, particularly with root sprouts, which can reach in the first year and in 4 years. Root sprouts often result in dense thickets, and a single tree, if allowed to spread unrestrained, will soon be surrounded by a sizable clonal colony

A clonal colony or genet is a group of genetically identical individuals, such as plants, fungi, or bacteria, that have grown in a given location, all originating vegetatively, not sexually, from a single ancestor. In plants, an individual in ...

, as its roots extend in every direction and send up multitudes of shoots.Keeler, H. L. (1900). ''Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them''. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

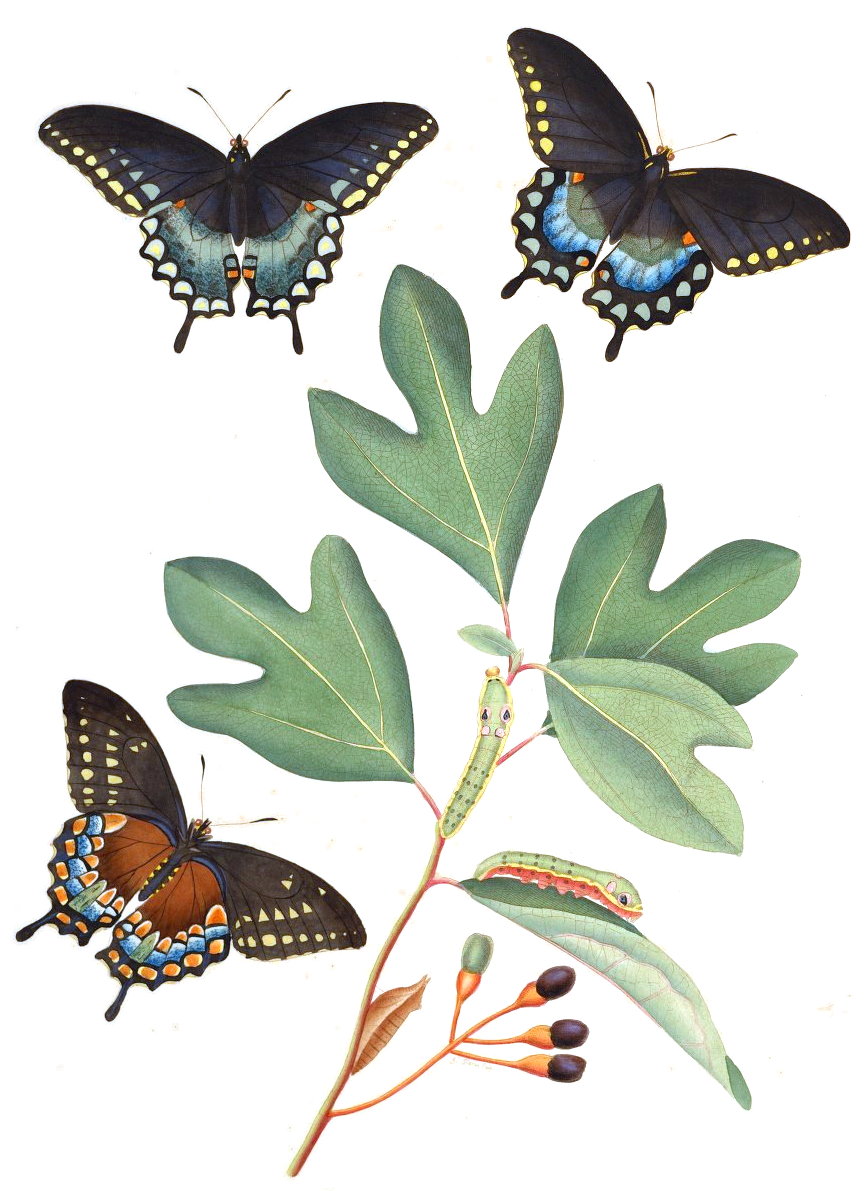

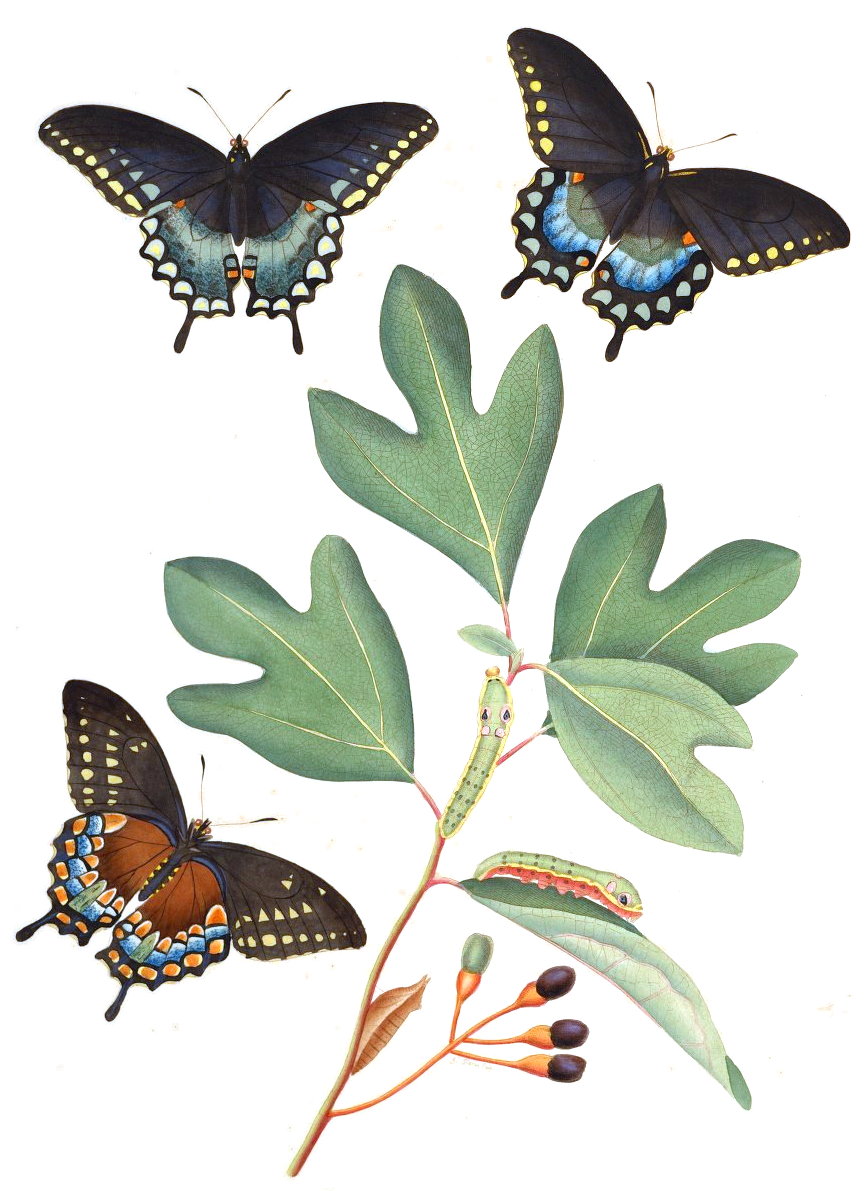

''S. albidum'' is a host plant for the caterpillar of the promethea silkmoth, '' Callosamia promethea''.

Laurel wilt

Laurel wilt

Laurel wilt, also called laurel wilt disease, is a vascular disease that is caused by the fungus ''Raffaelea lauricola'', which is transmitted by the invasive redbay ambrosia beetle, ''Xyleborus glabratus''. The disease affects and kills member ...

is a highly destructive disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

initiated when the invasive flying redbay ambrosia beetle (''Xyleborus glabratus'') introduces its highly virulent

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ...

fungal symbiont

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or paras ...

(''Raffaelea lauricola

Laurel wilt, also called laurel wilt disease, is a vascular disease that is caused by the fungus ''Raffaelea lauricola'', which is transmitted by the invasive redbay ambrosia beetle, ''Xyleborus glabratus''. The disease affects and kills member ...

'') into the sapwood

Wood is a porous and fibrous structural tissue found in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulose fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin t ...

of Lauraceae

Lauraceae, or the laurels, is a plant family that includes the true laurel and its closest relatives. This family comprises about 2850 known species in about 45 genera worldwide (Christenhusz & Byng 2016 ). They are dicotyledons, and occur m ...

host shrubs or trees. Sassafras's volatile terpenoids may attract ''X. glabratus''. Sassafras is susceptible to laurel wilt and capable of supporting broods of ''X. glabratus''. Underground transmission of the pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a ger ...

through roots and stolons of Sassafras without evidence of ''X. glabratus'' attack is suggested. Studies examining the insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

's cold tolerance

Psychrophiles or cryophiles (adj. ''psychrophilic'' or ''cryophilic'') are extremophile, extremophilic organisms that are capable of cell growth, growth and reproduction in low temperatures, ranging from to . They have an optimal growth temperat ...

showed that ''X. glabratus'' may be able to move

Move may refer to:

People

* Daniil Move (born 1985), a Russian auto racing driver

Brands and enterprises

* Move (company), an online real estate company

* Move (electronics store), a defunct Australian electronics retailer

* Daihatsu Move

...

to colder northern areas where sassafras would be the main host. The exotic

Exotic may refer to:

Mathematics and physics

* Exotic R4, a differentiable 4-manifold, homeomorphic but not diffeomorphic to the Euclidean space R4

*Exotic sphere, a differentiable ''n''-manifold, homeomorphic but not diffeomorphic to the ordinar ...

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

n insect is spreading

Spread may refer to:

Places

* Spread, West Virginia

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Spread'' (film), a 2009 film.

* ''$pread'', a quarterly magazine by and for sex workers

* "Spread", a song by OutKast from their 2003 album '' Speakerboxxx ...

the epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious d ...

from the Everglades

The Everglades is a natural region

A natural region (landscape unit) is a basic geographic unit. Usually, it is a region which is distinguished by its common natural features of geography, geology, and climate.

From the ecological point o ...

through the Carolinas

The Carolinas are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina, considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia to the southwest. The Atlantic Ocean is to the east.

Combining Nort ...

in perhaps less than 15 years by the end of 2014.

Uses

All parts of the ''Sassafras albidum'' plant have been used for human purposes, including stems, leaves, bark, wood, roots, fruit, and flowers. ''Sassafras albidum'', while native to North America, is significant to the economic, medical, and cultural history of both Europe and North America. In North America, it has particular culinary significance, being featured in distinct national foods such as traditional

All parts of the ''Sassafras albidum'' plant have been used for human purposes, including stems, leaves, bark, wood, roots, fruit, and flowers. ''Sassafras albidum'', while native to North America, is significant to the economic, medical, and cultural history of both Europe and North America. In North America, it has particular culinary significance, being featured in distinct national foods such as traditional root beer

Root beer is a sweet North American soft drink traditionally made using the root bark of the sassafras tree '' Sassafras albidum'' or the vine of ''Smilax ornata'' (known as sarsaparilla, also used to make a soft drink, sarsaparilla) as the ...

, filé powder

Filé powder, also called gumbo filé, is a spicy herb made from the dried and ground leaves of the North American sassafras tree ''( Sassafras albidum)''.

Culinary use

Filé powder is used in Louisiana Creole cuisine in the making of some ty ...

, and Louisiana Creole cuisine

Louisiana Creole cuisine (french: cuisine créole, lou, manjé kréyòl, es, cocina criolla) is a style of cooking originating in Louisiana, United States, which blends West African, French, Spanish, and Amerindian influences,

as well a ...

. ''Sassafras albidum'' was an important plant to many Native Americans of the southeastern United States and was used for many purposes, including culinary and medicinal purposes, before the European colonization of North America. Its significance for Native Americans is also magnified, as the European quest for sassafras as a commodity for export brought Europeans into closer contact with Native Americans during the early years of European settlement in the 16th and 17th centuries, in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, a ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

, and parts of the Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

.

Use by Native Americans

Southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also referred to as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical region of the United States. It is located broadly on the eastern portion of the southern United States and the southern po ...

prior to the European colonization. The Choctaw word for sassafras is "Kvfi," and it was by them principally as a soup thickener. It was known as "Winauk" in Delaware and Virginia and is called "Pauame" by the Timuca.

Some Native American tribes used the leaves of sassafras to treat wounds by rubbing the leaves directly into a wound, and used different parts of the plant for many medicinal purposes such as treating acne, urinary disorders, and sicknesses that increased body temperature, such as high fevers. They also used the bark as a dye, and as a flavoring.

Sassafras wood was also used by Native Americans in the Southeastern United States as a fire-starter because of the flammability of its natural oils.

In cooking, sassafras was used by some Native Americans to flavor bear fat, and to cure meats. Sassafras is still used today to cure meats. Use of filé powder by the Choctaw in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

in cooking is linked to the development of gumbo, a signature dish of Louisiana Creole cuisine

Louisiana Creole cuisine (french: cuisine créole, lou, manjé kréyòl, es, cocina criolla) is a style of cooking originating in Louisiana, United States, which blends West African, French, Spanish, and Amerindian influences,

as well a ...

.

Modern culinary use and legislation

''Sassafras albidum'' is used primarily in the United States as the key ingredient in home brewed root beer and as a thickener and flavouring in traditional

''Sassafras albidum'' is used primarily in the United States as the key ingredient in home brewed root beer and as a thickener and flavouring in traditional Louisiana Creole

Louisiana Creole ( lou, Kréyòl Lalwizyàn, links=no) is a French-based creole language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly in the state of Louisiana. It is spoken today by people who may racially identify as White, Black, mixed, and ...

gumbo.

Filé powder, also called gumbo filé, for its use in making gumbo, is a spicy herb made from the dried and ground leaves of the sassafras tree. It was traditionally used by Native Americans in the Southern United States, and was adopted into Louisiana Creole cuisine. Use of filé powder by the Choctaw in the Southern United States in cooking is linked to the development of gumbo, the signature dish of Louisiana Creole cuisine that features ground sassafras leaves. The leaves and root bark can be pulverized to flavor soup and gravy, and meat, respectively.

Sassafras roots are used to make traditional root beer, although they were banned for commercially mass-produced foods and drugs by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

in 1960. Laboratory animals that were given oral doses of sassafras tea or sassafras oil that contained large doses of safrole

Safrole is an organic compound with the formula CH2O2C6H3CH2CH=CH2. It is a colorless oily liquid, although impure samples can appear yellow. A member of the phenylpropanoid family of natural products, it is found in sassafras plants, among oth ...

developed permanent liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it ...

damage or various types of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal bl ...

. In humans, liver damage can take years to develop and it may not have obvious signs. Along with commercially available sarsaparilla, sassafras remains an ingredient in use among hobby or microbrew enthusiasts. While sassafras is no longer used in commercially produced root beer and is sometimes substituted with artificial flavors, natural extracts with the safrole distilled and removed are available. Most commercial root beers have replaced the sassafras extract with methyl salicylate, the ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ...

found in wintergreen

Wintergreen is a group of aromatic plants. The term "wintergreen" once commonly referred to plants that remain green (continue photosynthesis) throughout the winter. The term "evergreen" is now more commonly used for this characteristic.

Mos ...

and black birch (''Betula lenta'') bark.

Sassafras tea was also banned in the U.S. in 1977, but the ban was lifted with the passage of the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act

The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 ("DSHEA"), is a 1994 statute of United States Federal legislation which defines and regulates dietary supplements. Under the act, supplements are regulated by the FDA for Good Manufacturing P ...

in 1994.

Safrole oil, aromatic uses, MDMA

Safrole can be obtained fairly easily from the root bark of ''Sassafras albidum'' via steam distillation. It has been used as a natural insect or pest deterrent. Godfrey's Cordial, as well as other tonics given to children that consisted of

Safrole can be obtained fairly easily from the root bark of ''Sassafras albidum'' via steam distillation. It has been used as a natural insect or pest deterrent. Godfrey's Cordial, as well as other tonics given to children that consisted of opiates

An opiate, in classical pharmacology, is a substance derived from opium. In more modern usage, the term ''opioid'' is used to designate all substances, both natural and synthetic, that bind to opioid receptors in the brain (including antagonist ...

, used sassafras to disguise other strong smells and odours associated with the tonics. It was also used as an additional flavouring to mask the strong odours of homemade liquor in the United States.

camphor

Camphor () is a waxy, colorless solid with a strong aroma. It is classified as a terpenoid and a cyclic ketone. It is found in the wood of the camphor laurel ('' Cinnamomum camphora''), a large evergreen tree found in East Asia; and in the k ...

production in Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

or comes from related trees in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

. Safrole

Safrole is an organic compound with the formula CH2O2C6H3CH2CH=CH2. It is a colorless oily liquid, although impure samples can appear yellow. A member of the phenylpropanoid family of natural products, it is found in sassafras plants, among oth ...

is a precursor for the manufacture of the drug MDMA

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), commonly seen in tablet form (ecstasy) and crystal form (molly or mandy), is a potent empathogen–entactogen with stimulant properties primarily used for recreational purposes. The desired ...

, as well as the drug MDA (3-4 methylenedioxyamphetamine) and as such, its transport is monitored internationally. Safrole is a List I precursor chemical according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA; ) is a Federal law enforcement in the United States, United States federal law enforcement agency under the U.S. Department of Justice tasked with combating drug trafficking and distribution within th ...

.

The wood

Wood is a porous and fibrous structural tissue found in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulose fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of ligni ...

is dull orange brown, hard, and durable in contact with the soil; it was used in the past for posts and rails, small boats and ox-yokes, though scarcity and small size limits current use. Some is still used for making furniture

Furniture refers to movable objects intended to support various human activities such as seating (e.g., stools, chairs, and sofas), eating ( tables), storing items, eating and/or working with an item, and sleeping (e.g., beds and hammocks) ...

.Missouriplants''Sassafras albidum''

/ref>

History of commercial use

Europeans were first introduced to sassafras, along with other plants such as cranberries,tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ch ...

, and North American ginseng

Ginseng () is the root of plants in the genus '' Panax'', such as Korean ginseng ('' P. ginseng''), South China ginseng ('' P. notoginseng''), and American ginseng ('' P. quinquefolius''), typically characterized by the presence of ginsenosides ...

, when they arrived in North America.

The aromatic smell of sassafras was described by early European settlers arriving in North America. According to one legend, Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

found North America because he could smell the scent of sassafras. As early as the 1560s, French visitors to North America discovered the medicinal qualities of sassafras, which was also exploited by the Spanish who arrived in Florida. English settlers at Roanoke Island, Roanoke reported surviving on boiled sassafras leaves and dog meat during times of starvation.

Upon the arrival of the English on the Eastern coast of North America, sassafras trees were reported as plentiful. Sassafras was sold in England and in continental Europe, where it was sold as a dark beverage called "saloop" that had medicinal qualities and used as a medicinal cure for a variety of ailments. The discovery of sassafras occurred at the same time as a severe syphilis outbreak in Europe, when little about this terrible disease was understood, and sassafras was touted as a cure. Sir Francis Drake was one of the earliest to bring sassafras to England in 1586, and Sir Walter Raleigh was the first to export sassafras as a commodity in 1602. Sassafras became a major export commodity to England and other areas of Europe, as a medicinal root used to treat Fever, ague (fevers) and sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea, and as wood prized for its beauty and durability.Tiffany Leptuck, "Medical Attributes of 'Sassafras albidum' - Sassafras"], Kenneth M. Klemow, Ph.D., Wilkes-Barre University, 2003 Exploration for sassafras was the catalyst for the 1603 commercial expedition from Bristol of Captain Martin Pring to the coasts of present-day Maine

Maine () is a U.S. state, state in the New England and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and territories of Canad ...

, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. During a brief period in the early 17th century, sassafras was the second-largest export from the British colonies in North America behind tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ch ...

.Martin Pring, "The Voyage of Martin Pring, 1603"Summary of his life and expeditions at American Journeys website, 2012, Wisconsin Historical Society Since the bark was the most commercially valued part of the sassafras plant due to large concentrations of the aromatic safrole oil, commercially valuable sassafras could only be gathered from each tree once. This meant that as significant amounts of sassafras bark were gathered, supplies quickly diminished and sassafras become more difficult to find. For example, while one of the earliest shipments of sassafras in 1602 weighed as much as a ton, by 1626, English colonists failed to meet their 30-pound quota. The gathering of sassafras bark brought European settlers and Native Americans into contact sometimes dangerous to both groups. Sassafras was such a desired commodity in England, that its importation was included in the Charter of the Colony of Virginia in 1610. Through modern times the sassafras plant, both wild and cultivated, has been harvested for the extraction of safrole, which is used in a variety of commercial products as well as in the manufacture of illegal drugs like MDMA; yet, sassafras plants in China and Brazil are more commonly used for these purposes than North American ''Sassafras albidum''.

Gallery

See also

* Filé powder * Root beer * Sarsaparilla (soft drink), Sarsaparilla * Sassafras hesperia * Sassafras randaiense * Sassafras tzumuReferences

External links

{{Taxonbar, from=Q584469 Dioecious plants Lauraceae Medicinal plants Plants described in 1818 Trees of Ontario Trees of the Eastern United States Trees of North America Trees of the Southeastern United States Trees of the United States Trees of the Northeastern United States Trees of the Great Lakes region (North America) Trees of the North-Central United States Trees of the Southern United States