Sabbath (witchcraft) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Witches' Sabbath is a purported gathering of those believed to practice

The most infamous and influential work of witch-hunting lore, ''

The most infamous and influential work of witch-hunting lore, '' Lea and Hansen's influence may have led to a much broader use of the shorthand phrase, including in English. Prior to Hansen, use of the term by German historians also seems to have been relatively rare. A compilation of German folklore by Jakob Grimm in the 1800s () seems to contain no mention of ''hexensabbat'' or any other form of the term ''sabbat'' relative to fairies or magical acts. The contemporary of Grimm and early historian of witchcraft, W.G. Soldan also does not seem to use the term in his history (1843).

Lea and Hansen's influence may have led to a much broader use of the shorthand phrase, including in English. Prior to Hansen, use of the term by German historians also seems to have been relatively rare. A compilation of German folklore by Jakob Grimm in the 1800s () seems to contain no mention of ''hexensabbat'' or any other form of the term ''sabbat'' relative to fairies or magical acts. The contemporary of Grimm and early historian of witchcraft, W.G. Soldan also does not seem to use the term in his history (1843).

In 1668, a late date relative to the major European witch trials, German writer Johannes Praetorius published "Blockes-Berges Verrichtung", with the subtitle "Oder Ausführlicher Geographischer Bericht/ von den hohen trefflich alt- und berühmten Blockes-Berge: ingleichen von der Hexenfahrt/ und Zauber-Sabbathe/ so auff solchen Berge die Unholden aus gantz Teutschland/ Jährlich den 1. Maij in Sanct-Walpurgis Nachte anstellen sollen". As indicated by the subtitle, Praetorius attempted to give a "Detailed Geographical Account of the highly admirable ancient and famous Blockula, also about the witches' journey and magic sabbaths".

Writing more than two hundred years after Pierre de Lancre, another French writer, Lamothe-Langon (whose character and scholarship was questioned in the 1970s), uses the term in (presumably) translating into French a handful of documents from the inquisition in Southern France. Joseph Hansen cited Lamothe-Langon as one of many sources.

In 1668, a late date relative to the major European witch trials, German writer Johannes Praetorius published "Blockes-Berges Verrichtung", with the subtitle "Oder Ausführlicher Geographischer Bericht/ von den hohen trefflich alt- und berühmten Blockes-Berge: ingleichen von der Hexenfahrt/ und Zauber-Sabbathe/ so auff solchen Berge die Unholden aus gantz Teutschland/ Jährlich den 1. Maij in Sanct-Walpurgis Nachte anstellen sollen". As indicated by the subtitle, Praetorius attempted to give a "Detailed Geographical Account of the highly admirable ancient and famous Blockula, also about the witches' journey and magic sabbaths".

Writing more than two hundred years after Pierre de Lancre, another French writer, Lamothe-Langon (whose character and scholarship was questioned in the 1970s), uses the term in (presumably) translating into French a handful of documents from the inquisition in Southern France. Joseph Hansen cited Lamothe-Langon as one of many sources.

In

In

Carlo Ginzburg's researches have highlighted shamanic elements in European witchcraft compatible with (although not invariably inclusive of) drug-induced altered states of consciousness. In this context, a persistent theme in European witchcraft, stretching back to the time of classical authors such as

Carlo Ginzburg's researches have highlighted shamanic elements in European witchcraft compatible with (although not invariably inclusive of) drug-induced altered states of consciousness. In this context, a persistent theme in European witchcraft, stretching back to the time of classical authors such as

witchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

and other ritual

A ritual is a repeated, structured sequence of actions or behaviors that alters the internal or external state of an individual, group, or environment, regardless of conscious understanding, emotional context, or symbolic meaning. Traditionally ...

s. The phrase became especially popular in the 20th century.

Origin of the phrase

The most infamous and influential work of witch-hunting lore, ''

The most infamous and influential work of witch-hunting lore, ''Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise about witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic Church, Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinisation of names, Latini ...

'' (1486) does not contain the word sabbath ().

The first recorded English use of ''sabbath'' referring to sorcery was in 1660, in Francis Brooke's translation of Vincent Le Blanc's book ''The World Surveyed'': "Divers Sorcerers ��have confessed that in their Sabbaths ��they feed on such fare." The phrase "Witches' Sabbath" appeared in a 1613 translation by "W.B." of Sébastien Michaëlis's ''Admirable History of Possession and Conversion of a Penitent Woman'': "He also said to Magdalene, Art not thou an accursed woman, that the Witches Sabbath ( French: ''le Sabath''] is kept here?"

The phrase is used by Henry Charles Lea in his ''History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages'' (1888). Writing in 1900, German historian Joseph Hansen, who was a correspondent and a German translator of Lea's work, frequently uses the shorthand phrase ''hexensabbat'' to interpret medieval trial records, though any consistently recurring term is noticeably rare in the copious Latin sources Hansen also provides (see more on various Latin synonyms, below).

Lea and Hansen's influence may have led to a much broader use of the shorthand phrase, including in English. Prior to Hansen, use of the term by German historians also seems to have been relatively rare. A compilation of German folklore by Jakob Grimm in the 1800s () seems to contain no mention of ''hexensabbat'' or any other form of the term ''sabbat'' relative to fairies or magical acts. The contemporary of Grimm and early historian of witchcraft, W.G. Soldan also does not seem to use the term in his history (1843).

Lea and Hansen's influence may have led to a much broader use of the shorthand phrase, including in English. Prior to Hansen, use of the term by German historians also seems to have been relatively rare. A compilation of German folklore by Jakob Grimm in the 1800s () seems to contain no mention of ''hexensabbat'' or any other form of the term ''sabbat'' relative to fairies or magical acts. The contemporary of Grimm and early historian of witchcraft, W.G. Soldan also does not seem to use the term in his history (1843).

A French connection

In contrast to German and English counterparts, French writers (including Francophone authors writing in Latin) used the term more frequently, albeit still relatively rarely. There seems to be deep roots to inquisitorial persecution of theWaldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

. In 1124, the term ''inzabbatos'' is used to describe the Waldensians in Northern Spain. In 1438 and 1460, seemingly related terms ''synagogam'' and ''synagogue of Sathan'' are used to describe Waldensians by inquisitors in France. These terms could be a reference to Revelation 2:9 ("I know the blasphemy of them which say they are Jews and are not, but are the synagogue of Satan.") Writing in Latin in 1458, Francophone author Nicolas Jacquier applies ''synagogam fasciniorum'' to what he considers a gathering of witches.

About 150 years later, near the peak of the witch-phobia and the persecutions which led to the execution of an estimated 40,000-100,000 persons, with roughly 80% being women, the Francophone

The Francophonie or Francophone world is the whole body of people and organisations around the world who use the French language regularly for private or public purposes. The term was coined by Onésime Reclus in 1880 and became important a ...

writers still seem to be the main ones using these related terms, although still infrequently and sporadically in most cases. Lambert Daneau uses ''sabbatha'' one time (1581) as ''Synagogas quas Satanica sabbatha''. Nicholas Remi uses the term occasionally as well as ''synagoga'' (1588). Jean Bodin

Jean Bodin (; ; – 1596) was a French jurist and political philosopher, member of the Parlement of Paris and professor of law in Toulouse. Bodin lived during the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and wrote against the background of reli ...

uses the term three times (1580) and, across the channel, the Englishman Reginald Scot

Reginald Scot (or Scott) ( – 9 October 1599) was an Englishman and Member of Parliament, the author of '' The Discoverie of Witchcraft'', which was published in 1584. It was written against the belief in witches, to show that witchcraft ...

(1585) writing a book in opposition to witch-phobia, uses the term but only once in quoting Bodin.

In 1611, Jacques Fontaine uses ''sabat'' five times writing in French and in a way that would seem to correspond with modern usage. The following year (1612), Pierre de Lancre

Pierre de Rosteguy de Lancre or Pierre de l'Ancre, Lord of De Lancre (1553–1631), was the French judge of Bordeaux who conducted the massive Labourd witch-hunt of 1609. In 1582 he was named judge in Bordeaux, and in 1608 Henry IV of France, Kin ...

seems to use the term more frequently than anyone before.

In 1668, a late date relative to the major European witch trials, German writer Johannes Praetorius published "Blockes-Berges Verrichtung", with the subtitle "Oder Ausführlicher Geographischer Bericht/ von den hohen trefflich alt- und berühmten Blockes-Berge: ingleichen von der Hexenfahrt/ und Zauber-Sabbathe/ so auff solchen Berge die Unholden aus gantz Teutschland/ Jährlich den 1. Maij in Sanct-Walpurgis Nachte anstellen sollen". As indicated by the subtitle, Praetorius attempted to give a "Detailed Geographical Account of the highly admirable ancient and famous Blockula, also about the witches' journey and magic sabbaths".

Writing more than two hundred years after Pierre de Lancre, another French writer, Lamothe-Langon (whose character and scholarship was questioned in the 1970s), uses the term in (presumably) translating into French a handful of documents from the inquisition in Southern France. Joseph Hansen cited Lamothe-Langon as one of many sources.

In 1668, a late date relative to the major European witch trials, German writer Johannes Praetorius published "Blockes-Berges Verrichtung", with the subtitle "Oder Ausführlicher Geographischer Bericht/ von den hohen trefflich alt- und berühmten Blockes-Berge: ingleichen von der Hexenfahrt/ und Zauber-Sabbathe/ so auff solchen Berge die Unholden aus gantz Teutschland/ Jährlich den 1. Maij in Sanct-Walpurgis Nachte anstellen sollen". As indicated by the subtitle, Praetorius attempted to give a "Detailed Geographical Account of the highly admirable ancient and famous Blockula, also about the witches' journey and magic sabbaths".

Writing more than two hundred years after Pierre de Lancre, another French writer, Lamothe-Langon (whose character and scholarship was questioned in the 1970s), uses the term in (presumably) translating into French a handful of documents from the inquisition in Southern France. Joseph Hansen cited Lamothe-Langon as one of many sources.

A term favored by recent translators

Despite the infrequency of the use of the word ''sabbath'' to denote any such gatherings in the historical record, it became increasingly popular during the 20th century.Cautio Criminalis

In a 2003 translation of Friedrich Spee's ''Cautio Criminalis'' (1631) the word ''sabbaths'' is listed in the index with a large number of entries. However, unlike some of Spee's contemporaries in France (mentioned above), who occasionally, if rarely, use the term ''sabbatha'', Friedrich Spee does not ever use words derived from ''sabbatha'' or ''synagoga''. Spee was German-speaking, and like his contemporaries, wrote in Latin. ''Conventibus'' is the word Spee uses most frequently to denote a gathering of witches, whether supposed or real, physical or spectral, as seen in the first paragraph of question one of his book. This is the same word from which English words ''convention'', ''convent'', and ''coven'' are derived. ''Cautio Criminalis'' (1631) was written as a passionate innocence project. As a Jesuit, Spee was often in a position of witnessing the torture of those accused of witchcraft.Malleus Maleficarum

In a 2009 translation of Dominican inquisitor Heinrich Kramer's ''Malleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise about witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic Church, Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinisation of names, Latini ...

'' (1486), the word ''sabbath'' does not occur. There is a line describing a supposed gathering that uses the word ''concionem''; it is accurately translated as an ''assembly''. However in the accompanying footnote, the translator seems to apologize for the lack of both the term ''sabbath'' and a general scarcity of other gatherings that would seem to fit the bill for what he refers to as a "black sabbath".

Fine art

The phrase is also popular in recent translations of the titles of artworks, including: * ''The Witches' Sabbath'' by Hans Baldung (1510) * ''Witches' Sabbath'' by Frans Francken (1606) * ''Witches' Sabbath in Roman Ruins'' by Jacob van Swanenburgh (1608) * As a recent translation from the original Spanish ''El aquelarre'' to the English title '' Witches' Sabbath'' (1798) and ''Witches' Sabbath'' or ''The Great He-Goat'' (1823) both works byFrancisco Goya

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (; ; 30 March 1746 – 16 April 1828) was a Spanish Romanticism, romantic painter and Printmaking, printmaker. He is considered the most important Spanish artist of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Hi ...

* '' Muse of the Night (Witches' Sabbath)'' by Luis Ricardo Falero

Luis Ricardo Falero (23 May 1851 – 7 December 1896) was a Spanish painter. He specialized in female nudes and mythological, orientalist and fantasy settings.

In 1896, the year of his death, Maud Harvey sued Falero for paternity. The s ...

(1880)

Music

In

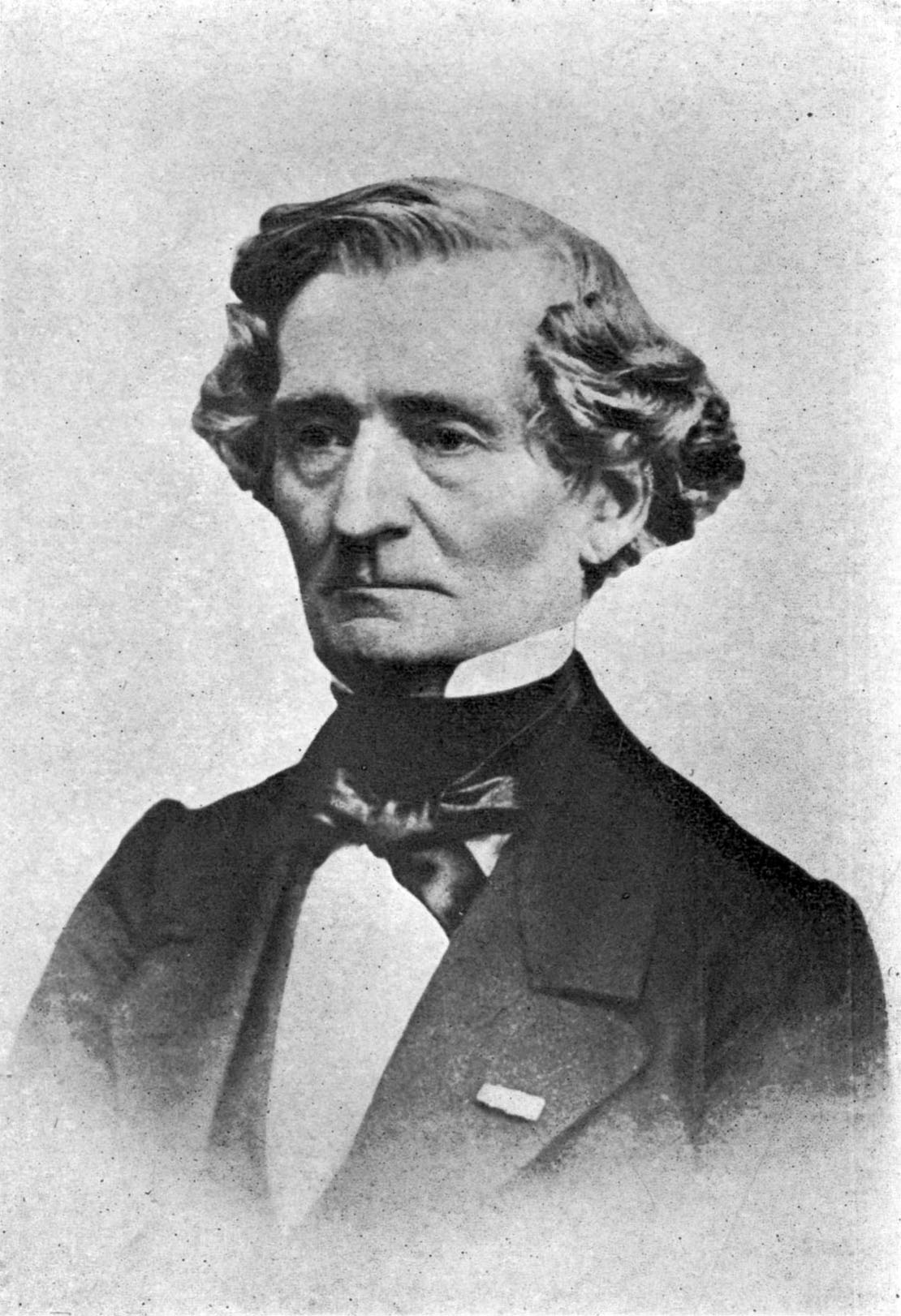

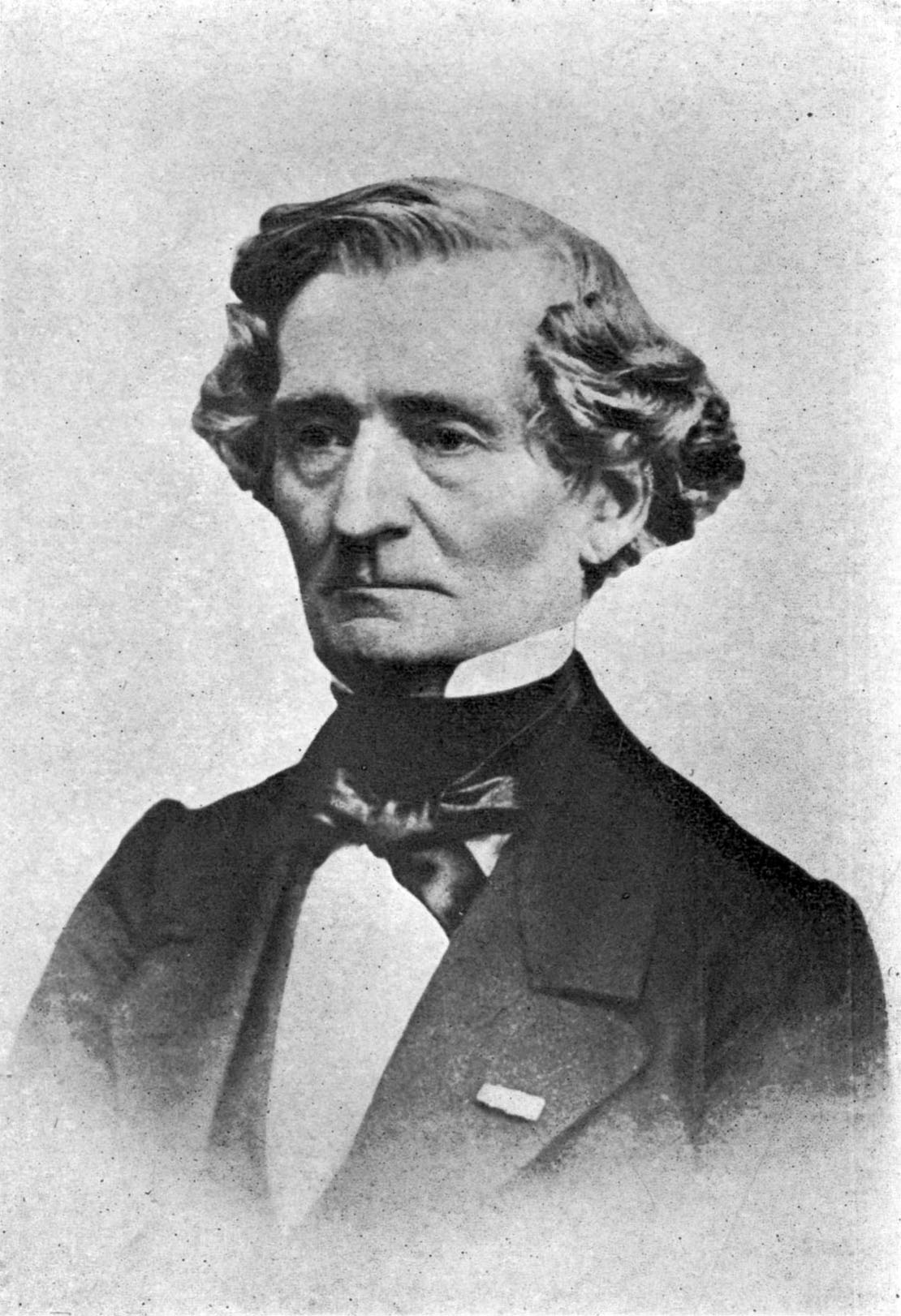

In Hector Berlioz

Louis-Hector Berlioz (11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) was a French Romantic music, Romantic composer and conductor. His output includes orchestral works such as the ''Symphonie fantastique'' and ''Harold en Italie, Harold in Italy'' ...

's ''Symphonie Fantastique

' (''Fantastic Symphony: Episode in the Life of an Artist … in Five Sections'') Opus number, Op. 14, is a program music, programmatic symphony written by Hector Berlioz in 1830. The first performance was at the Paris Conservatoire on 5 December ...

'', the fifth and final movement of the composition is titled ''"Hexensabbath"'' in German and ''"Songe d'une nuit du Sabbat"'' in French, strangely having two different meanings. In the popular English editions of the symphony, the title of the movement is ''"Dream of a Witches' Sabbath"'', a mixture of the two translations. The setting of the movement is in a satanic dream depicting the protagonist's own funeral. Crowds of sorcerers and monsters stand around him, laughing, shouting, and screeching. The protagonist's beloved appears as a witch, distorted from her previous beauty.

Disputed accuracy of the accounts of gatherings

Modern researchers have been unable to find any corroboration with the notion that physical gatherings of practitioners of witchcraft occurred. In his study "The Pursuit of Witches and the Sexual Discourse of the Sabbat", the historian Scott E. Hendrix presents a two-fold explanation for why these stories were so commonly told in spite of the fact that sabbats likely never actually occurred. First, belief in the real power of witchcraft grew during the late medieval and early-modern Europe as a doctrinal view in opposition to the canon Episcopi gained ground in certain communities. This fueled a paranoia among certain religious authorities that there was a vast underground conspiracy of witches determined to overthrow Christianity. Women beyond child-bearing years provided an easy target and were scapegoated and blamed for famines, plague, warfare, and other problems. Having prurient and orgiastic elements helped ensure that these stories would be relayed to others.Ritual elements

Bristol University

The University of Bristol is a public research university in Bristol, England. It received its royal charter in 1909, although it can trace its roots to a Merchant Venturers' school founded in 1595 and University College, Bristol, which had ...

's Ronald Hutton has encapsulated the witches' sabbath as an essentially modern construction, saying:

The book '' Compendium Maleficarum'' (1608), by Francesco Maria Guazzo, illustrates a typical view of gathering of witches as "the attendants riding flying goats, trampling the cross, and being re-baptised in the name of the Devil while giving their clothes to him, kissing his behind, and dancing back to back forming a round."

In effect, the sabbat acted as an effective 'advertising' gimmick, causing knowledge of what these authorities believed to be the very real threat of witchcraft to be spread more rapidly across the continent. That also meant that stories of the sabbat promoted the hunting, prosecution, and execution of supposed witches.

The descriptions of Sabbats were made or published by priests, jurists and judges who never took part in these gatherings, or were transcribed during the process of the witchcraft trials. That these testimonies reflect actual events is for most of the accounts considered doubtful. Norman Cohn argued that they were determined largely by the expectations of the interrogators and free association on the part of the accused, and reflect only popular imagination of the times, influenced by ignorance

Ignorance is a lack of knowledge or understanding. Deliberate ignorance is a culturally-induced phenomenon, the study of which is called agnotology.

The word "ignorant" is an adjective that describes a person in the state of being unaware, or ...

, fear

Fear is an unpleasant emotion that arises in response to perception, perceived dangers or threats. Fear causes physiological and psychological changes. It may produce behavioral reactions such as mounting an aggressive response or fleeing the ...

and religious intolerance towards minority groups.

Some of the existing accounts of the Sabbat were given when the person recounting them was being torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

d, and so motivated to agree with suggestions put to them.

Christopher F. Black claimed that the Roman Inquisition's sparse employment of torture allowed accused witches to not feel pressured into mass accusation. This in turn means there were fewer alleged groups of witches in Italy and places under inquisitorial influence. Because the Sabbath is a gathering of collective witch groups, the lack of mass accusation means Italian popular culture was less inclined to believe in the existence of Black Sabbath. The Inquisition itself also held a skeptical view toward the legitimacy of Sabbath Assemblies.

Many of the diabolical elements of the Witches' Sabbath stereotype, such as the eating of babies, poisoning of wells, desecration of hosts or kissing of the devil's anus, were also made about heretical Christian sects, leper

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria '' Mycobacterium leprae'' or '' Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve da ...

s, Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s and Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

s. The term is the same as the normal English word "Sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, Ten Commandments, commanded by God to be kept as a Holid ...

" (itself a transliteration of Hebrew "Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; , , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazi Hebrew, Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the seven-day week, week—i.e., Friday prayer, Friday–Saturday. On this day, religious Jews ...

", the seventh day, on which the Creator rested after creation of the world), referring to the witches' equivalent to the Christian day of rest; a more common term was "synagogue" or " synagogue of Satan" possibly reflecting anti-Jewish sentiment, although the acts attributed to witches bear little resemblance to the Sabbath in Christianity

Many Christians observe a weekly day set apart for rest and worship called a Sabbath in obedience to God's commandment to remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.

Early Christians, at first mainly Jewish, observed the seventh-day (Saturday) S ...

or Jewish Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; , , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazi Hebrew, Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the seven-day week, week—i.e., Friday prayer, Friday–Saturday. On this day, religious Jews ...

customs. The ''Errores Gazariorum'' ("''Errors of the Cathars"''), which mentions the Sabbat, while not discussing the actual behavior of the Cathars, is named after them, in an attempt to link these stories to an heretical Christian group.

More recently, scholars such as Emma Wilby

Emma Wilby is a British historian and author specialising in the magic (paranormal), magical beliefs of Early Modern period, Early Modern Britain.

Work

An honorary fellow in history at the University of Exeter, England, and a Fellow of the Royal ...

have argued that although the more diabolical elements of the witches' sabbath stereotype were invented by inquisitors, the witchcraft suspects themselves may have encouraged these ideas to circulate by drawing on popular beliefs and experiences around liturgical misrule, cursing rites, magical conjuration and confraternal gatherings to flesh-out their descriptions of the sabbath during interrogations.

Christian missionaries' attitude to African cults was not much different in principle to their attitude to the Witches' Sabbath in Europe; some accounts viewed them as a kind of Witches' Sabbath, but they are not. Some African communities believe in witchcraft, but as in the European witch trials, people they believe to be "witches" are condemned rather than embraced.

Possible connections to real groups

Other historians, including Carlo Ginzburg, Éva Pócs, Bengt Ankarloo and Gustav Henningsen hold that these testimonies can give insights into the belief systems of the accused. Ginzburg famously discovered records of a group of individuals inNorthern Italy

Northern Italy (, , ) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. The Italian National Institute of Statistics defines the region as encompassing the four Northwest Italy, northwestern Regions of Italy, regions of Piedmo ...

, calling themselves ''benandanti

The () were members of an agrarian visionary tradition in the Friuli district of Northeastern Italy during the 16th and 17th centuries. The claimed to travel out of their bodies while asleep to struggle against malevolent sorcerers (; ) in order ...

'', who believed that they went out of their bodies in spirit and fought amongst the clouds against evil spirits to secure prosperity for their villages, or congregated at large feasts presided over by a goddess, where she taught them magic and performed divinations. Ginzburg links these beliefs with similar testimonies recorded across Europe, from the ''armiers'' of the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

, from the followers of Signora Oriente Madonna Oriente or Signora Oriente (Lady of the East), also known as La Signora del Gioco (The Lady of the Game), are names of an alleged religious figure, as described by two Italian women who were executed by the Inquisition in 1390 as witches.

T ...

in fourteenth century Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

and the followers of Richella and 'the wise Sibillia' in fifteenth century northern Italy, and much further afield, from Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

n werewolves

In folklore, a werewolf (), or occasionally lycanthrope (from Ancient Greek ), is an individual who can shapeshift into a wolf, or especially in modern film, a therianthropic hybrid wolf–humanlike creature, either purposely or after bei ...

, Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

n '' kresniki'', Hungarian ''táltos

The táltos (; also "tátos") is a figure in Hungarian mythology, a person with supernatural power similar to a shaman.

Description

The most reliable account of the táltos is given by Roman Catholic priest Arnold Ipolyi in his collection of fol ...

'', Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

n '' căluşari'' and Ossetian ''burkudzauta''. In many testimonies, these meetings were described as out-of-body, rather than physical, occurrences.

Role of topically-applied hallucinogens

Carlo Ginzburg's researches have highlighted shamanic elements in European witchcraft compatible with (although not invariably inclusive of) drug-induced altered states of consciousness. In this context, a persistent theme in European witchcraft, stretching back to the time of classical authors such as

Carlo Ginzburg's researches have highlighted shamanic elements in European witchcraft compatible with (although not invariably inclusive of) drug-induced altered states of consciousness. In this context, a persistent theme in European witchcraft, stretching back to the time of classical authors such as Apuleius

Apuleius ( ), also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis (c. 124 – after 170), was a Numidians, Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He was born in the Roman Empire, Roman Numidia (Roman province), province ...

,

is the use of unguents conferring the power of "flight" and "shape-shifting." Recipes for such "flying ointments" have survived from early modern times, permitting not only an assessment of their likely pharmacological effects – based on their various plant (and to a lesser extent animal) ingredients – but also the actual recreation of and experimentation with such fat or oil-based preparations. Ginzburg makes brief reference to the use of entheogens in European witchcraft at the end of his analysis of the Witches Sabbath, mentioning only the fungi Claviceps purpurea

''Claviceps purpurea'' is an ergot fungus that grows on the ear (botany), ears of rye and related cereal and forage plants. Consumption of Cereal, grains or seeds contaminated with the survival structure of this fungus, the ergot sclerotium, can ...

and Amanita muscaria

''Amanita muscaria'', commonly known as the fly agaric or fly amanita, is a basidiomycete fungus of the genus ''Amanita''. It is a large white-lamella (mycology), gilled, white-spotted mushroom typically featuring a bright red cap covered with ...

by name, and stating about the "flying ointment" on page 303 of 'Ecstasies...' :

In the Sabbath the judges more and more frequently saw the accounts of real, physical events. For a long time the only dissenting voices were those of the people who, referring back to the ''– in short, a substrate of shamanic myth could, when catalysed by a drug experience (or simple starvation), give rise to a 'journey to the Sabbath', not of the body, but of the mind. Ergot and the Fly Agaric mushroom, while hallucinogenic, were not among the ingredients listed in recipes for the flying ointment. The active ingredients in such unguents were primarily, not fungi, but plants in the nightshade familyCanon episcopi The title canon ''Episcopi'' (or ''capitulum Episcopi'') is conventionally given to a certain passage found in medieval canon law. The text possibly originates in an early 10th-century penitential, recorded by Regino of Prüm; it was included in ...'', saw witches and sorcerers as the victims of demonic illusion. In the sixteenth century scientists like Cardano or Della Porta formulated a different opinion : animal metamorphoses, flights, apparitions of the devil were the effect of malnutrition or the use of hallucinogenic substances contained in vegetable concoctions or ointments...But no form of privation, no substance, no '' ecstatic technique'' can, by itself, cause the recurrence of such complex experiences...the deliberate use of psychotropic or hallucinogenic substances, while not explaining the ecstasies of the followers of the nocturnal goddess, thewerewolf In folklore, a werewolf (), or occasionally lycanthrope (from Ancient Greek ), is an individual who can shapeshifting, shapeshift into a wolf, or especially in modern film, a Shapeshifting, therianthropic Hybrid beasts in folklore, hybrid wol ..., and so on, would place them in a not exclusively mythical dimension.

Solanaceae

Solanaceae (), commonly known as the nightshades, is a family of flowering plants in the order Solanales. It contains approximately 2,700 species, several of which are used as agricultural crops, medicinal plants, and ornamental plants. Many me ...

, most commonly Atropa belladonna

''Atropa bella-donna'', commonly known as deadly nightshade or belladonna, is a toxic perennial herbaceous plant in the nightshade family Solanaceae, which also includes tomatoes, potatoes and eggplant. It is native to Europe and Western Asia, i ...

(Deadly Nightshade) and Hyoscyamus niger

Henbane (''Hyoscyamus niger'', also black henbane and stinking nightshade) is a poisonous plant belonging to tribe Hyoscyameae of the nightshade family ''Solanaceae''. Henbane is native to temperate Europe and Siberia, and naturalised in Great B ...

(Henbane), belonging to the tropane

Tropane is a nitrogenous bicyclic organic compound. It is mainly known for the other alkaloids derived from it, which include atropine and cocaine, among others. Tropane alkaloids occur in plants of the families Erythroxylaceae (including coca) ...

alkaloid-rich tribe Hyoscyameae

Hyoscyameae is an Old World Tribe (biology), tribe of the subfamily Solanoideae of the flowering plant family Solanaceae. It comprises seven genera: ''Anisodus'', ''Atropa'', ''Atropanthe'', ''Hyoscyamus'', ''Physochlaina'', ''Przewalskia'' and ' ...

. Other tropane-containing, nightshade ingredients included the Mandrake Mandragora officinarum, Scopolia carniolica and Datura stramonium

''Datura stramonium'', known by the common names thornapple, jimsonweed (jimson weed), or devil's trumpet, is a poisonous flowering plant in the ''Datureae, Daturae'' Tribe (botany), tribe of the nightshade family Solanaceae. Its likely origi ...

, the Thornapple.

The alkaloids Atropine

Atropine is a tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic medication used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. It is typically give ...

, Hyoscyamine

Hyoscyamine (also known as daturine or duboisine) is a naturally occurring tropane alkaloid and plant toxin. It is a secondary metabolite found in certain plants of the family Solanaceae, including Hyoscyamus niger, henbane, Mandragora officina ...

and Scopolamine present in these Solanaceous plants are not only potent and highly toxic hallucinogens, but are also fat-soluble and capable of being absorbed through unbroken human skin.Sollmann, Torald, A Manual of Pharmacology and Its Applications to Therapeutics and Toxicology. 8th edition. Pub. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia and London 1957.

See also

* * * * * * '' Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath'' – 1989 book by Carlo Ginzburg * * * * * Shabbat Chazon - Sabbath of Vision, aka "Black Sabbath" * *References

Further reading

* – See the chapter "The Role of Hallucinogenic Plants in European Witchcraft" * The first modern attempt to outline the details of the medieval Witches' Sabbath. * Chapter IV, ''The Sabbat'' has detailed description of Witches' Sabbath, with complete citations of sources. * See also the extensive topic bibliography to the primary literature on pg. 560. *Musgrave, James Brent and James Houran. (1999). "The Witches' Sabbat in Legend and Literature." ''Lore and Language'' 17, no. 1-2. pg 157–174. *Wilby, Emma. (2013) "Burchard's Strigae, the Witches' Sabbath, and Shamnistic Cannibalism in Early Modern Europe." ''Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft'' 8, no.1: 18–49. * *Sharpe, James. (2013) "In Search of the English Sabbat: Popular Conceptions of Witches' Meetings in Early Modern England. ''Journal of Early Modern Studies''. 2: 161–183. *Hutton, Ronald. (2014) "The Wild Hunt and the Witches' Sabbath." ''Folklore''. 125, no. 2: 161–178. *Roper, Lyndal. (2004) Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany. -''See Part II: Fantasy Chapter 5: Sabbaths *Thompson, R.L. (1929) ''The History of the Devil- The Horned God of the West- Magic and Worship.'' *Murray, Margaret A. (1962)''The Witch-Cult in Western Europe.'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press) *Black, Christopher F. (2009) ''The Italian Inquisition''. (New Haven: Yale University Press). See Chapter 9- The World of Witchcraft, Superstition and Magic *Ankarloo, Bengt and Gustav Henningsen. (1990) ''Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press). see the following essays- pg 121 Ginzburg, Carlo "Deciphering the Sabbath," pg 139 Muchembled, Robert "Satanic Myths and Cultural Reality," pg 161 Rowland, Robert. "Fantastically and Devilishe Person's: European Witch-Beliefs in Comparative Perspective," pg 191 Henningsen, Gustav "'The Ladies from outside': An Archaic Pattern of Witches' Sabbath." *Wilby, Emma. (2005) ''Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic visionary traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic''. (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press) *Garrett, Julia M. (2013) "Witchcraft and Sexual Knowledge in Early Modern England," ''Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies'' 13, no. 1. pg 32–72. *Roper, Lyndal. (2006) "Witchcraft and the Western Imagination," ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'' 6, no. 16. pg 117–141. {{Witchcraft European witchcraft Sabbath