SMS Gazelle (1859) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS ''Gazelle'' was an screw-driven

''Gazelle'' remained out of service for the next few years. At the outbreak of the

''Gazelle'' remained out of service for the next few years. At the outbreak of the

''Gazelle'' was next recommissioned on 2 June 1874, under the command of KzS Georg von Schleinitz. Beginning in 1869, the Royal Saxon Society for the Sciences had requested the navy send ships to observe the next

''Gazelle'' was next recommissioned on 2 June 1874, under the command of KzS Georg von Schleinitz. Beginning in 1869, the Royal Saxon Society for the Sciences had requested the navy send ships to observe the next

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

of the Prussian Navy

The Prussian Navy (German language, German: ''Preußische Marine''), officially the Royal Prussian Navy (German Language, German: ''Königlich Preußische Marine''), was the naval force of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1701 to 1867.

The Prussian N ...

built in the 1850s. The class comprised five ships, and were the first major steam-powered warships ordered for the Prussian Navy. The ships were ordered as part of a major construction program to strengthen the nascent Prussian fleet, under the direction of Prince Adalbert, and were intended to provide defense against the Royal Danish Navy

The Royal Danish Navy (, ) is the Naval warfare, sea-based branch of the Danish Armed Forces force. The RDN is mainly responsible for maritime defence and maintaining the sovereignty of Denmark, Danish territorial waters (incl. Faroe Islands and ...

. ''Gazelle'' was armed with a battery

Battery or batterie most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

* Battery indicator, a device whic ...

of twenty-six guns, and was capable of steaming at a speed of . ''Gazelle'' was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

in 1855, launched in 1859, and commissioned in 1862.

The ship's first major operation began in late 1862, when she was chosen to carry the ratified treaties with Japan and China that had been concluded by the Eulenburg expedition The Eulenburg expedition was a diplomatic mission conducted by Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg on behalf of Prussia and the German Customs Union in 1859–1862. Its aim was to establish diplomatic and commercial relations with China, Japan and Siam. ...

. While in the latter country in early 1864, the Second Schleswig War

The Second Schleswig War (; or German Danish War), also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War, was the second military conflict over the Schleswig–Holstein question of the nineteenth century. The war began on 1 Februar ...

against Denmark had broken out, and ''Gazelle'' attacked Danish merchant shipping in Asia, capturing four prizes

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

before the war ended. She eventually arrived home in 1865. ''Gazelle'' was mobilized

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

during the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

of 1866, but saw no action during the short conflict that resulted in the creation of the Prussian-dominated North German Confederation

The North German Confederation () was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated state (a ''de facto'' feder ...

. She cruised in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

on a training voyage for naval cadet

Officer cadet is a rank held by military personnel during their training to become commissioned officers. In the United Kingdom, the rank is also used by personnel of University Service Units such as the University Officers' Training Corps.

Th ...

s in 1866–1867, now a warship of the North German Federal Navy

The North German Federal Navy (''Norddeutsche Bundesmarine'' or ''Marine des Norddeutschen Bundes''), was the Navy of the North German Confederation, formed out of the Prussian Navy in 1867. It was eventually succeeded by the Imperial German Navy ...

.

''Gazelle'' was not recommissioned during the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

, owing to the vast superiority of the French fleet. Now in the service of the (Imperial Navy) of unified Germany, ''Gazelle'' made a cruise to the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

from 1871 to 1873, sailing alone, at times with her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same Ship class, class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They o ...

, and ending the voyage with a larger squadron. From 1874 to 1876, ''Gazelle'' embarked on a major overseas voyage for scientific purposes, including part of Germany's observation of the 1874 transit of Venus

The 1874 transit of Venus, which took place on 9 December 1874 (01:49 to 06:26 UTC), was the first of the pair of transits of Venus that took place in the 19th century, with the second transit occurring eight years later in 1882. The previous ...

. The scientific team aboard the ship also conducted ethnographic

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

, zoological

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

, and oceanographic

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of top ...

research during the cruise. ''Gazelle'' was sent to the Mediterranean in 1877 in response to heightened tensions that eventually resulted in the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

in 1878. The ship saw limited service in the late 1870s and early 1880s, primarily as a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house class ...

, before being struck from the naval register

A Navy Directory, Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval authorities of a co ...

in 1884. She was used as a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

until 1906, when she was sold to ship breakers

Ship breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship scrapping, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships either as a source of parts, which can be sold for re-use, or for t ...

.

Design

In the immediate aftermath of theFirst Schleswig War

The First Schleswig War (), also known as the Schleswig-Holstein uprising () and the Three Years' War (), was a military conflict in southern Denmark and northern Germany rooted in the Schleswig–Holstein question: who should control the Du ...

against Denmark, Prince Adalbert began drawing up plans for the future of the Prussian Navy

The Prussian Navy (German language, German: ''Preußische Marine''), officially the Royal Prussian Navy (German Language, German: ''Königlich Preußische Marine''), was the naval force of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1701 to 1867.

The Prussian N ...

; he also secured the Jade Treaty

The Jade Treaty () of 20 July 1853 between the Kingdom of Prussia and the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg provided for the handover of 340 hectares of Oldenburg territory at what is now Wilhelmshaven, Germany, on the western shore of the Jade Bight, a bay ...

that saw the port of Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsha ...

transferred to Prussia from the Duchy of Oldenburg

The Duchy of Oldenburg (), named for its capital, the town of Oldenburg, was a state in the north-west of present-day Germany. The counts of Oldenburg died out in 1667, after which it became a duchy until 1810, when it was annexed by the First ...

, and which provided the Prussian fleet with an outlet on the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

. Adalbert called for a force of three screw frigate

Steam frigates (including screw frigates) and the smaller steam corvettes, steam sloops, steam gunboats and steam schooners, were steam-powered warships that were not meant to stand in the line of battle. The first such ships were paddle stea ...

s and six screw corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the sloo ...

s to protect Prussian maritime trade in the event of another war with Denmark. Design work was carried out between 1854 and 1855, and the first two ships were authorized in November 1855; a further pair was ordered in June 1860, and the final member of the class was ordered in February 1866.

''Gazelle'' was long overall

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and is also u ...

and had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Radio beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially lo ...

of and a draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

of forward. She displaced as designed and at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into weig ...

. The ship had short forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck (ship), deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is t ...

and sterncastle

The aftercastle (or sterncastle, sometimes aftcastle) is the stern structure behind the mizzenmast and above the transom on large sailing ships, such as carracks, caravels, galleons and galleasses. It usually houses the captain's cabin and per ...

decks. Her superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

consisted primarily of a small deckhouse

A cabin or berthing is an enclosed space generally on a ship or an aircraft. A cabin which protrudes above the level of a ship's deck may be referred to as a deckhouse.

Sailing ships

In sailing ships, the officers and paying passengers wou ...

aft. She had a crew of 35 officers and 345 enlisted men.

Her propulsion system consisted of a single horizontal single-expansion steam engine driving a single screw propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

, with steam supplied by four coal-burning fire-tube boiler

A fire-tube boiler is a type of boiler invented in 1828 by Marc Seguin, in which hot gases pass from a fire through one or more tubes running through a sealed container of water. The heat of the gases is transferred through the walls of the tube ...

s. Exhaust was vented through a single funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its constructi ...

located amidships. ''Gazelle'' was rated to steam at a top speed of , but she significantly exceeded this speed, reaching from . The ship had a cruising radius of about at a speed of . To supplement the steam engine on long voyages abroad, she carried a full-ship rig with a total surface area of . The screw could be retracted while cruising under sail.

''Gazelle'' was armed with a battery

Battery or batterie most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

* Battery indicator, a device whic ...

of six 68-pounder guns and twenty 36-pounder guns. By 1870, she had been rearmed with a uniform battery of seventeen RK L/22 guns; later in her career, the number of these guns was reduced to eight.

Service history

Construction and initial operations

After being ordered on 2 November 1855, the ship waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

on 3 December at the Royal Dockyard

Royal Navy Dockyards (more usually termed Royal Dockyards) were state-owned harbour facilities where ships of the Royal Navy were built, based, repaired and refitted. Until the mid-19th century the Royal Dockyards were the largest industrial c ...

in Danzig. Work on the ship, which was named for the species of antelope, proceeded slowly owing to the very limited naval budgets of the period, along with delays in the delivery of her propulsion system. The lengthy construction time had the positive effect of allowing the ship's timbers to properly season before the hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

was completed. She was launched without ceremony on 19 December 1859, and despite the pressing need for a warship to be sent to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

in response to the unrest in Italy during the unification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century Political movement, political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, annexation of List of historic states of ...

, work continued slowly. The ship's first officer arrived on 5 June 1860 to oversee completion of the ship, including her rigging. Further delays were caused by the unreliable engines manufactured by AG Vulcan

Aktien-Gesellschaft Vulcan Stettin (short AG Vulcan Stettin) was a German shipbuilding and locomotive building company. Founded in 1851, it was located near the former eastern German city of Szczecin, Stettin, today Polish Szczecin. Because of th ...

, which had only been founded in 1857. The originally planned training cruise scheduled for 1861 had to be cancelled, and the sail frigate was sent instead.

''Gazelle'' was eventually completed on 22 May 1861, and commissioned into the Navy almost a year later on 15 May 1862. Her first commander was (KK—Corvette Captain) Eduard Heldt, who captained the ship during her initial sea trials

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on o ...

and maiden voyage. Her full complement of sailors arrived by 3 July, along with the naval cadet

Officer cadet is a rank held by military personnel during their training to become commissioned officers. In the United Kingdom, the rank is also used by personnel of University Service Units such as the University Officers' Training Corps.

Th ...

s of the 1860 and 1861 crew years. In early August, ''Gazelle'' departed on her first overseas trip, a training cruise to Brest, France

Brest (; ) is a port, port city in the Finistère department, Brittany (administrative region), Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of a peninsula and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an impor ...

, which she reached on 31 August. After a two-week stay, the ship departed Brest on 15 September, bound for Neufahrwasser, Prussia. ''Gazelle'' was intended to be deployed to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

in 1863—a right extended to several European powers after the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

on 1853–1856—diplomatic events in East Asia

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

saw these plans changed. The Eulenburg expedition The Eulenburg expedition was a diplomatic mission conducted by Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg on behalf of Prussia and the German Customs Union in 1859–1862. Its aim was to establish diplomatic and commercial relations with China, Japan and Siam. ...

, carried out aboard the frigate , had resulted in the signing of treaties with Siam

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

, Qing China

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the Ming dynasty ...

, and Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. Japan demanded that a proper warship return to complete the ratification purpose, and ''Gazelle'' was chosen for the mission.

1862–1865 overseas cruise

''Gazelle'' received orders to embark on the voyage to the Far East on 23 October 1862, and she departed from Neufahrwasser on 9 November. By 21 November, she had reachedGibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, where the crew visited a recently erected monument to the Prussian sailors who had died in the Battle of Tres Forcas

The Battle of Tres Forcas was a battle on 7 August 1856 between boat crews from the Prussian Navy corvette SMS ''Danzig'' (then on a foreign cruise, commanded by Heinrich Adalbert) and the Berber Riffians. It occurred at Cape Tres Forcas in Mo ...

in 1856. While still in Gibraltar in December, Heldt was replaced by KK Arthur von Bothwell, who was to captain the ship for the rest of the cruise. ''Gazelle'' got underway again in late January 1863, sailing initially west to Brazil, arriving in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

in February. There, Emperor Pedro I of Brazil

''Don (honorific), Dom'' Pedro I (12 October 1798 – 24 September 1834), known in Brazil and in Portugal as "the Liberator" () or "the Soldier King" () in Portugal, was the founder and List of monarchs of Brazil, first ruler of the Empire of ...

visited the ship. ''Gazelle'' thereafter sailed back across the Atlantic, passing the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

, stopping in Anjer

Anyer, also known as Anjer or Angier, is a coastal town in Banten, formerly West Java, Indonesia, west of Jakarta and south of Merak. A significant coastal town late 18th century, Anyer faces the Sunda Strait.

History

The town was a considerab ...

on the island of Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

in the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

, before arriving in Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

on 31 May. The ship remained here until early July, when she sailed for Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

, China, which she reached on 10 July. There, the Prussian consul general

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

, Guido von Rehfues, came aboard the ship with a staff of five men. Rehfeus was to carry out the formal ratification of the treaties. ''Gazelle'' departed on 15 July, passing through Amoy

Xiamen,), also known as Amoy ( ; from the Zhangzhou Hokkien pronunciation, zh, c=, s=, t=, p=, poj=Ē͘-mûi, historically romanized as Amoy, is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Stra ...

on the way to Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

, where she remained from 21 to 30 July. The ship then sailed for Yokohama

is the List of cities in Japan, second-largest city in Japan by population as well as by area, and the country's most populous Municipalities of Japan, municipality. It is the capital and most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a popu ...

, Japan, arriving on 8 August.

Upon arriving in Yokohama, ''Gazelle'' found a diplomatic crisis. The isolationist Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars ...

had abrogated all foreign treaties and had begun expelling foreigners from the country. A civil conflict had also broken out between some of the daimyo

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and nominally to ...

s, and the Satsuma Domain

The , briefly known as the , was a Han system, domain (''han'') of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan during the Edo period from 1600 to 1871.

The Satsuma Domain was based at Kagoshima Castle in Satsuma Province, the core of the modern city of ...

had opened hostilities with the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. The British squadron left Yokohama the day that ''Gazelle'' arrived; the city had a significant European settlement, and several French warships took responsibility for defending it, sending some 300 men ashore with field gun

A field gun is a field artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march, that when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances (field artillery ...

s. The French commander requested that Bothwell support them, so ''Gazelle'' contributed a landing party of 107 men and two 12-pounder guns to reinforce the garrison. Soon thereafter, the British bombarded Kagoshima, inflicting significant damage and hardening Japanese anger at the Europeans. Bothwell sent another fifty men ashore to further strengthen the force in Yokohama. In the meantime, Rehfues attempted to negotiate a settlement, which was reached in November. The Japanese revoked their ban on foreign residents, and on 2 January 1864, ''Gazelle'' arrived in Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

, where the treaty that had been signed during the Eulenberg mission was formally ratified on 21 January. Later that day, after the Prussian ambassador Max von Brandt

Maximilian August Scipio von Brandt (born 8 October 1835 in Berlin; died 24 August 1920 in Weimar) was a German diplomat, East Asia expert and publicist.

Biography

Max von Brandt was the son of Prussian general and military author Heinrich von ...

arrived, ''Gazelle'' sailed from Tokyo, stopping in Yokohama and Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

on the way to Shanghai, where she stayed from 8 March to 6 April.

While in Shanghai, Bothwell learned of the start of the Second Schleswig War

The Second Schleswig War (; or German Danish War), also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War, was the second military conflict over the Schleswig–Holstein question of the nineteenth century. The war began on 1 Februar ...

between Prussia and Denmark; he received orders to begin cruiser warfare against Danish merchant shipping. The ship disembarked the Prussian diplomatic delegation at Tianjin

Tianjin is a direct-administered municipality in North China, northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the National Central City, nine national central cities, with a total population of 13,866,009 inhabitants at the time of the ...

, who then traveled to Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

; ''Gazelle'' thereafter began searching for Danish ships to attack. Her first cruise in Chinese waters was unsuccessful, but on her second voyage to Japan, she captured schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

''Falk'' on 25 April; the brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the l ...

''Caroline'' of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig (; ; ; ; ; ) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km (45 mi) south of the current border between Germany and Denmark. The territory has been di ...

-Holstein

Holstein (; ; ; ; ) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider (river), Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost States of Germany, state of Germany.

Holstein once existed as the German County of Holstein (; 8 ...

of 26 April; and on 5 May, the Danish brig ''Caterine''. The Prussians later released ''Caroline''. Orders to return home arrived in Beijing on 5 May, which ''Gazelle'' received when she stopped in Yantai

Yantai, formerly known as Chefoo, is a coastal prefecture-level city on the Shandong Peninsula in northeastern Shandong province of the People's Republic of China. Lying on the southern coast of the Bohai Strait, Yantai borders Qingdao ...

, China, on 19 May. She then moved to Xiamen

Xiamen,), also known as Amoy ( ; from the Zhangzhou Hokkien pronunciation, zh, c=, s=, t=, p=, poj=Ē͘-mûi, historically romanized as Amoy, is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Stra ...

, China, before capturing the Danish schooner ''Chin-Chin''; Bothwell was unaware that an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

had ended the fighting in the Second Schleswig War. The ship thereafter stopped in Hong Kong in early June and then sailed on to Singapore, where she stayed from 16 July to early August. ''Gazelle'' passed through Anjer again on the way home and had reached Simon's Town

Simon's Town (), sometimes spelled Simonstown, is a town in the Western Cape, South Africa and is home to Naval Base Simon's Town, the South African Navy's largest base. It is located on the shores of Simon's Bay in False Bay, on the eastern s ...

, South Africa, by 14 September. Here, she received orders to sail through the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

to represent Prussia in the aftermath of the war. By 15 December, she had returned to European waters, anchoring in Cherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

, France, that day. There, she underwent repairs after her lengthy voyage abroad, and she was ready to sail for home on 1 May 1865. She reached Neufahrwasser eight days later and was decommissioned there on 3 June.

Operations in 1866

''Gazelle'' next recommissioned on 3 April 1866, as was with theAustrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

appeared to be imminent; the fleet received its mobilization

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

orders on 12 May shortly before the outbreak of the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

. The Prussian fleet assembled a squadron at Kiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

commanded by (Rear Admiral) Eduard von Jachmann

Eduard Karl Emanuel von Jachmann (2 March 1822 – 21 October 1887) was the first '' Vizeadmiral'' (vice admiral) of the Prussian Navy. He entered the navy in the 1840s after initially serving in the merchant marine. In 1848, Jachmann rece ...

, which ''Gazelle'' joined. The ship did not see action during the war, however. During a training cruise conducted in the western Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

later that year, a man went overboard, and a young naval cadet Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (; born Alfred Peter Friedrich Tirpitz; 19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral and State Secretary of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperi ...

nearly drowned in his attempt to rescue the sailor.

The ship received orders on 30 September to begin making preparations for a cruise in the Mediterranean. She moved to the recently acquired naval base at Geestemünde

Bremerhaven (; ) is a city on the east bank of the Weser estuary in northern Germany. It forms an exclave of the Bremen (state), city-state of Bremen. The Geeste (river), River Geeste flows through the city before emptying into the Weser.

Brem ...

, where further preparations were made. A class of naval cadets also arrived to fill the crew for the voyage; these were the 1864 and 1865 crew years. KK Ludwig von Henk arrived to take command of the ship in October. The ship got underway on 18 October, stopping in Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

, Britain, on her way through the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

. Repairs to her engine were carried out in Portsmouth in mid-November. From there, she continued on to Cadiz, Spain, and then entered the Mediterranean. During a stop in Valletta

Valletta ( ; , ) is the capital city of Malta and one of its 68 Local councils of Malta, council areas. Located between the Grand Harbour to the east and Marsamxett Harbour to the west, its population as of 2021 was 5,157. As Malta’s capital ...

, Malta, on 11 December she met the gunboat . ''Gazelle'' visited Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

and Civitavecchia

Civitavecchia (, meaning "ancient town") is a city and major Port, sea port on the Tyrrhenian Sea west-northwest of Rome. Its legal status is a ''comune'' (municipality) of Metropolitan City of Rome Capital, Rome, Lazio.

The harbour is formed by ...

, Italy in January and February 1867, followed by a return to Malta. By 8 March, she had arrived in Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, where she loaded relief supplies to be carried to the island of Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

, which had recently been struck by a major earthquake. While in Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, the Ottoman capital, she collided with the British merchant steamer ''Mercury''.

''Gazelle'' received orders to return home in mid-April, and she had reached Geestemünde by 12 June. There, she underwent repairs for the damage incurred in the collision, which lasted until 18 August, after which she returned to Kiel six days later. From there, she was moved to Danzig on 3 September, where she was decommissioned on 23 September for a more thorough overhaul. Her troublesome engine was repaired, and her armament was partially modernized with eight of the new guns. A subsequent inquiry into the accident in Constantinople determined that the ship's executive officer, Johannes Weickhmann, was responsible for the collision and that Henk had been asleep at the time.

1871–1873 cruise to the West Indies

''Gazelle'' remained out of service for the next few years. At the outbreak of the

''Gazelle'' remained out of service for the next few years. At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

in 1870, the Prussian Navy decided not to mobilize the ''Arcona''-class frigates. ''Gazelle'' was stationed at Kiel for the duration of the conflict. The small Prussian navy was significantly outnumbered by the powerful French fleet, and most of the Prussian strength was concentrated in a small squadron of ironclads

An ironclad was a steam-propelled warship protected by steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. The firs ...

based at Wilhelmshaven on the North Sea. The French attempted to blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are ...

the north German coasts, but withdrew having achieved little before the war was decided at the Battle of Sedan

The Battle of Sedan was fought during the Franco-Prussian War from 1 to 2 September 1870. Resulting in the capture of Napoleon III, Emperor Napoleon III and over a hundred thousand troops, it effectively decided the war in favour of Prussia and ...

. With the war over by early 1871, and the various German states now unified as the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

, the need to protect German trading activities abroad saw the recommissioning of ''Gazelle'' on 1 July. She was ordered to patrol the West Indies, and she sailed from Germany on 23 August and arrived in Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

on 24 October. From there, she sailed to La Guaira

La Guaira () is the capital city of the Venezuelan Vargas (state), state of the same name (formerly named Vargas) and the country's main port, founded in 1577 as an outlet for nearby Caracas.

The city hosts its own professional baseball team i ...

, Venezuela, to demand the repayment of Venezuelan debt to German companies that had been owed for several years. ''Gazelle'' was also needed to protect Germans living in the country, which was undergoing a period of civil unrest, and the local residents were growing increasingly hostile to Germans. The German chancellor, Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

, informed the United States government of the ship's activities to assuage concerns that Germany sought to claim a colony in the country.

The ship left Venezuela on 9 December and sailed to Santo Domingo

Santo Domingo, formerly known as Santo Domingo de Guzmán, is the capital and largest city of the Dominican Republic and the List of metropolitan areas in the Caribbean, largest metropolitan area in the Caribbean by population. the Distrito Na ...

after receiving news that the government of the Dominican Republic was considering signing an agreement that would give Germany a coaling station in the country. But the German government observed that such an agreement would be viewed by the United States as a violation of its Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

, and so abandoned the project. ''Gazelle'' then sailed on to Port-au-Prince

Port-au-Prince ( ; ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Haiti, most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 1,200,000 in 2022 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The me ...

, Haiti, arriving there on 19 December. There, the Germans hoped to secure payment of a debt that had been pending since 1868, but they were only able to obtain another promise of payment. She next sailed to Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house class ...

. ''Gazelle'' stopped in Pensacola

Pensacola ( ) is a city in the Florida panhandle in the United States. It is the county seat and only city in Escambia County. The population was 54,312 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Pensacola metropolitan area, which ha ...

, United States, on 1 April to embark the new German resident minister

A resident minister, or resident for short, is a government official required to take up permanent residence in another country. A representative of his government, he officially has diplomatic functions which are often seen as a form of ind ...

for Mexico. She then carried him to Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

, where a detachment of one officer and twenty men escorted him to Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

.

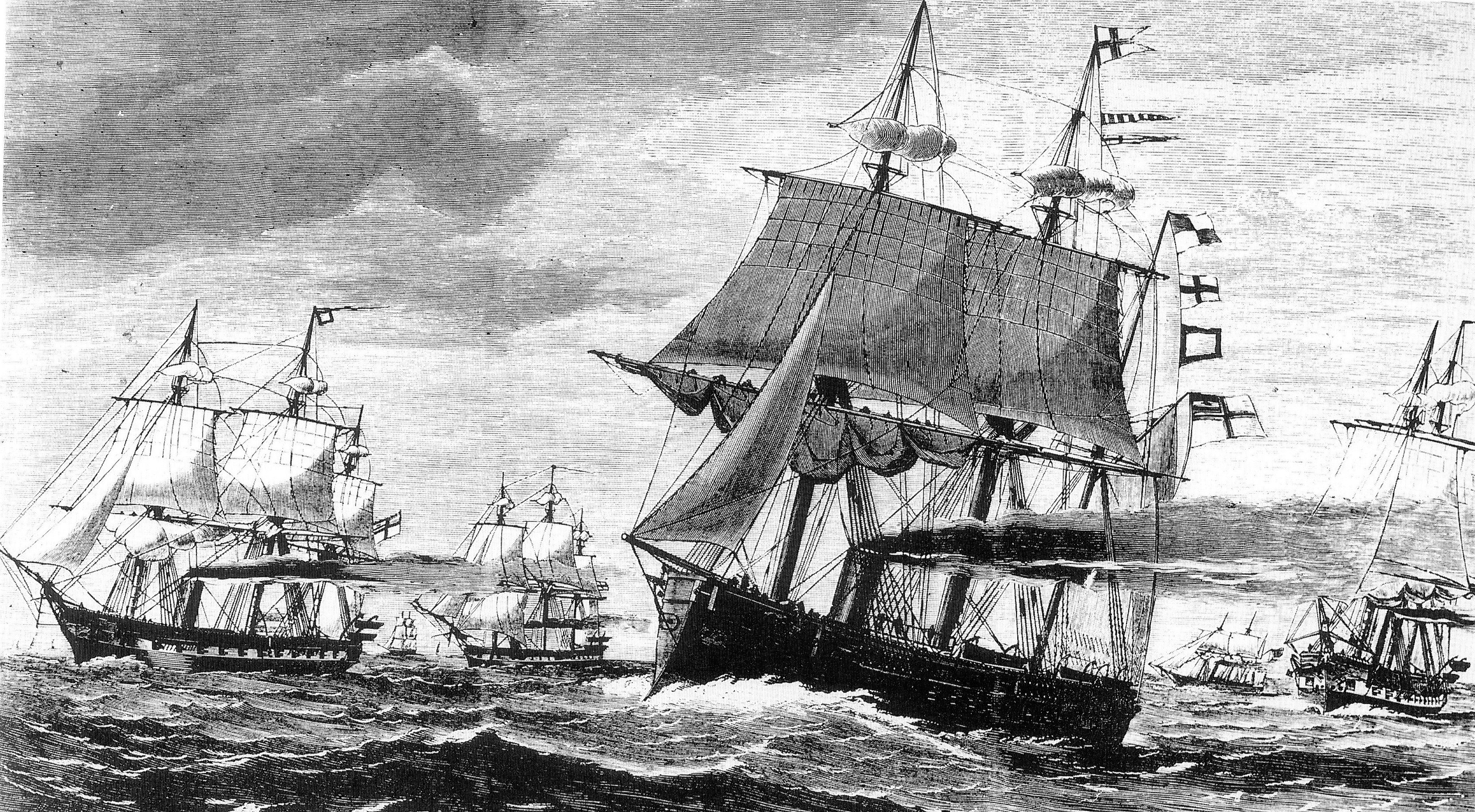

''Gazelle'' arrived back in Havana on 19 May, where she joined her sister . The latter's commander, (KzS—Captain at Sea) Carl Ferdinand Batsch, was senior to that of ''Gazelle'', so he took command of the two ships. They sailed back to Haiti to make another attempt to pressure the government to settle its debt to Germany. The Germans took a more forceful approach to secure payment, sending a landing party led by (Lieutenant) Friedrich von Hollmann

Friedrich von Hollmann (19 January 1842 – 21 January 1913) was an Admiral of the German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) and Secretary of the German Imperial Naval Office under Emperor Wilhelm II.

Naval career

Hollmann was born in Berlin ...

into the city while other sailors captured a pair of Haitian steamers. The Haitians promptly agreed to pay the debt and the ships suffered no casualties. They then cruised along the East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

to visit a number of cities. During this cruise, ''Gazelle'' was badly damaged in a severe storm and had to stop at the Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

on 4 September for repairs. She thereafter rejoined ''Vineta'', and the two ships returned to the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

. On 3 December, in Bridgetown

Bridgetown (UN/LOCODE: BB BGI) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Barbados. Formerly The Town of Saint Michael, the Greater Bridgetown area is located within the Parishes of Barbados, parish of Saint Michael, Barbados, Saint Mic ...

, Barbados, they joined a squadron that also included the ironclad , frigate , and the gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

. The unit was commanded by Reinhold von Werner. After three months of cruises in the region, the squadron was ordered home in March 1873. On reaching Plymouth, the ships dispersed on their voyages to different German ports; ''Gazelle'' sailed on alone to Kiel, arriving on 3 May. She was then moved to Danzig, where she was decommissioned on 26 May for another extensive overhaul.

1874–1876 scientific expedition

''Gazelle'' was next recommissioned on 2 June 1874, under the command of KzS Georg von Schleinitz. Beginning in 1869, the Royal Saxon Society for the Sciences had requested the navy send ships to observe the next

''Gazelle'' was next recommissioned on 2 June 1874, under the command of KzS Georg von Schleinitz. Beginning in 1869, the Royal Saxon Society for the Sciences had requested the navy send ships to observe the next transit of Venus

A transit of Venus takes place when Venus passes directly between the Sun and the Earth (or any other superior planet), becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a transit, Venus is visible as ...

, which was predicted to take place in December 1874. Bismarck took an interest in the request, and he ordered four stations be set up to observe the event: Isfahan

Isfahan or Esfahan ( ) is a city in the Central District (Isfahan County), Central District of Isfahan County, Isfahan province, Iran. It is the capital of the province, the county, and the district. It is located south of Tehran. The city ...

, Iran; Auckland

Auckland ( ; ) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. It has an urban population of about It is located in the greater Auckland Region, the area governed by Auckland Council, which includes outlying rural areas and ...

, New Zealand; Yantai, China; and Kerguelen

The Kerguelen Islands ( or ; in French commonly ' but officially ', ), also known as the Desolation Islands (' in French), are a group of islands in the sub-Antarctic region. They are among the most isolated places on Earth, with the closest t ...

in the southern Indian Ocean. ''Gazelle'' was to carry the team and equipment to the last site, owing to her good sailing characteristics. The polar explorer Georg von Neumayer

Georg Balthazar von Neumayer (21 June 1826 – 24 May 1909) was a German polar explorer and scientist who was a proponent of the idea of international cooperation for meteorology and scientific observation. He served as a hydrographer for the ...

suggested that the mission be expanded to include a variety of other scientific endeavors, including studies on oceanography

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of to ...

, geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

, ethnography

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

, and zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

. The navy agreed, and ''Gazelle'' was modified at Danzig for the expedition; half of her guns were removed, which meant that some fifty fewer crew was needed to man the ship. The vacated crew spaces were then converted to store various equipment needed for the studies, along with accommodations for the scientists. Researchers aboard included the zoologists Theophil Studer, Friedrich Carl Naumann, and Carl Hüesker, along with the astronomers Karl Börgen and Ladislaus Weinek, who would study the transit of Venus on 9 December 1874 at Kerguelen.

The ship moved to Kiel to complete preparations for the voyage, before departing on 21 June. The voyage would be the first major scientific cruise of the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

. ''Gazelle'' stopped in a number of ports along the way to her first destination, Monrovia

Monrovia () is the administrative capital city, capital and largest city of Liberia. Founded in 1822, it is located on Cape Mesurado on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast and as of the 2022 census had 1,761,032 residents, home to 33.5% of Liber ...

, Liberia, which she reached on 4 August. She spent the next three days here, conducting scientific work before continuing on. She next stopped in Banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large treelike herbaceous flowering plants in the genus '' Musa''. In some countries, cooking bananas are called plantains, distinguishing the ...

at the mouth of the Congo River in central Africa. During the ship's stay there from 2 to 8 September, the crew met the German Kingdom of Loango, Loango expedition led by Paul Güssfeldt. From 29 September to 4 October, ''Gazelle'' stopped in Simon's Town and Capetown in the British Cape Colony; there, the ship's instruments were calibrated to the observatory there. The ship then departed south, passing the Crozet Islands on her way to Kerguelen, which she reached on 26 October.

''Gazelle'' anchored in Betsy Cove in Accessible Bay, a location that had been surveyed by ''Arcona'' the year before. The scientists erected a research station there, and while they conducted their work, ''Gazelle'' conducted surveys of the island, including a previously unmapped peninsula that was named for Albrecht von Roon, a former Prussian naval minister. In late December, ''Gazelle'' temporarily left the island to rendezvous with the sailing ship ''Gabain'', which was en route to India, to transfer the results of the German observation of the transit of Venus as quickly as possible. The two ships met at sea on 3 January 1875, and the findings reached Berlin by 15 February.

''Gazelle'' departed Kerguelen with the researchers on 5 February and sailed north through the Indian Ocean; while on the way, she surveyed the islands of Île Amsterdam and Île Saint-Paul. The ship stopped in Port Louis on the island of Mauritius on 26 February, where the researchers were disembarked to return to Germany on a merchant vessel. ''Gazelle'' got underway again on 15 March, bound for Australia, and on the way, her crew conducted a series of depth soundings along the way to chart the ocean floor. She stopped briefly in Onslow, Western Australia, before soon proceeding on to Kupang in Timor, then part of the Dutch East Indies. ''Gazelle'' stayed in Kupang from 14 to 26 May, after which she moved to Ambon Island, where the ship remained from 2 to 6 July.

The ship then cruised along the coast of New Guinea through the end of September, also touring the Bismarck Archipelago. The crew mapped the region and collected ethnographical materials that were to be studied Ethnological Museum of Berlin. These operations in New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago would later prove to be very useful for Schleinitz when he later served as the (state governor) of the colony of German New Guinea in the 1880s. During the ship's operations in the region, the crew suffered severely from malnutrition, disease, and frequent changes of climate. The men also had to resort to cutting trees to burn in the ship's boilers, as there were no available coaling stations in the area; this was difficult work that increased the strain on the sailors. The conditions aboard the ship became so bad that she stopped in Brisbane, Australia, on 29 September to rest the crew. Upon arriving, it became necessary to quarantine the vessel until 14 October due to the number of sick crewmen aboard.

On 20 October, ''Gazelle'' sailed from Brisbane, bound for Auckland, where she stayed from 29 October to 11 November. From there, she sailed north, passing through Fiji and the Tonga Islands, before arriving in Apia in Samoa on 24 December. There, the Germans hoped to negotiate an economic agreement, but the island was still in midst of internal turmoil that had been encountered there during the earlier visit of the corvette . ''Gazelle'' left Samoa shortly thereafter to return home; she sailed east to South America and entered the Strait of Magellan on 1 February 1876. While transiting the strait, she stopped in Punta Arenas, Chile, where she met her sister ''Vineta'', which was also on a circumnavigation of the globe. During a stop in Montevideo, Uruguay, on 16 February, ''Gazelle'' met the British corvette , which was then nearing the end of Challenger expedition, its own scientific expedition. The ships' crews exchanged experiences on their extended voyages around the world.

''Gazelle'' reached Faial Island in the Azores on 10 April, and then stopped in Plymouth nine days later. She reached Kiel on 28 April, where she was decommissioned on 12 May. In the course of 23 months, the ship had sailed some over around 450 days at sea; two-thirds of the distance was covered under sail power alone. Sixteen men from her crew died during the voyage. Schleinitz was given an honorary Doctor of Philosophy in recognition of the expedition, which was judged to have been as significant as the contemporaneous ''Challenger'' expedition. Gazelle Harbor in Empress Augusta Bay on the island of Bougainville Island, Bougainville was named after the ship, along with the Gazelle Peninsula on New Britain, which terminates at Cape Gazelle.

Later career

In late 1876, ''Gazelle'' was recommissioned to serve as a training ship for engine room and fire room, boiler room crews, replacing ''Arcona'' in this role, as the latter vessel was in need of repairs. This service lasted from 6 November to 16 December, as it had become necessary to send the ship to the Mediterranean in response to the increase in tensions between the Ottoman Empire and Russia, which would eventually erupt into theRusso-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

of 1877–1878. She was briefly decommissioned on the 16th, before being recommissioned on 20 December under the command of KK Friedrich von Hacke. ''Gazelle'' got underway on 7 January 1877, and after arriving in the Mediterranean, she replaced the ironclad ''Friedrich Carl'' as the flagship of German naval forces in the region on 2 March. At the time, the other vessels in the Mediterranean included the gunboats and and the aviso . ''Gazelle'' initially visited ports in Asia Minor, the core territory of the Ottoman Empire. In early June, ''Meteor'' returned home, having been replaced by the corvette . On 14 July, now Batsch arrived with the ironclad training squadron, and he took Hacke's role as commander of German naval forces in the Mediterranean. ''Gazelle'' stopped in Valletta for an overhaul that lasted from 27 August to 8 October. She thereafter resumed cruising in the eastern Mediterranean, which lasted until early April 1878. She got underway to return home on 5 April, arriving in Wilhelmshaven on 11 May. She was decommissioned there nine days later.

''Gazelle'' was recommissioned again on 17 March 1879, once again to train crews for engine and boiler rooms; this lasted until 30 June, when she was again decommissioned. For most of this period, the ship was commanded by KzS Johann-Heinrich Pirner, though he left the ship in May. This service was repeated from 15 March to 30 June 1880, though she was also used for fisheries protection patrols during this period. ''Gazelle'' was recommissioned for the last time on 15 March 1881, though she remained part of the II Reserve; this year, she remained in commission until 6 July. She saw no further active service, and on 8 January 1884, she was struck from the naval register

A Navy Directory, Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval authorities of a co ...

. From 1887 to 1906, she was used as a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

for II Torpedo Division in Wilhelmshaven. She was sold for scrap in 1906 for 36,000 German gold mark, gold marks and broken up in the Netherlands.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Gazelle, SMS 1859 ships Ships built in Danzig Arcona-class frigates