SEALAB on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SEALAB I, II, and III were experimental

SEALAB I was commanded by Captain Bond, who became known as "Papa Topside". SEALAB I proved that saturation diving in the open ocean was viable for extended periods. The experiment also offered information about habitat placement, habitat umbilicals, humidity, and helium speech descrambling.

SEALAB I was lowered off the coast of

SEALAB I was commanded by Captain Bond, who became known as "Papa Topside". SEALAB I proved that saturation diving in the open ocean was viable for extended periods. The experiment also offered information about habitat placement, habitat umbilicals, humidity, and helium speech descrambling.

SEALAB I was lowered off the coast of

SEALAB II was launched in 1965. It was nearly twice as large as SEALAB I with heating coils installed in the deck to ward off the constant helium-induced chill, and air conditioning to reduce the oppressive humidity. Facilities included hot showers, a built-in toilet, laboratory equipment, eleven viewing ports, two exits, and

SEALAB II was launched in 1965. It was nearly twice as large as SEALAB I with heating coils installed in the deck to ward off the constant helium-induced chill, and air conditioning to reduce the oppressive humidity. Facilities included hot showers, a built-in toilet, laboratory equipment, eleven viewing ports, two exits, and

p. 173. A sidenote from SEALAB II was a congratulatory

According to John Piña Craven, the U.S. Navy's head of the Deep Submergence Systems Project of which SEALAB was a part, SEALAB III "was plagued with strange failures at the very start of operations". USS ''Elk River'' (IX-509) was specially fitted as a SEALAB operations support ship to replace ''Berkone''; but the project was 18 months late and three million dollars over budget when SEALAB III was lowered to off

According to John Piña Craven, the U.S. Navy's head of the Deep Submergence Systems Project of which SEALAB was a part, SEALAB III "was plagued with strange failures at the very start of operations". USS ''Elk River'' (IX-509) was specially fitted as a SEALAB operations support ship to replace ''Berkone''; but the project was 18 months late and three million dollars over budget when SEALAB III was lowered to off

Office of Naval Research

Photos from the 2002 High Performance Wireless Research and Education Network expedition to the SEALAB II/III habitat.

(One screen shot o

current habitat

* * * {{Authority control United States Navy in the 20th century Underwater habitats Scott Carpenter

underwater habitat

Underwater habitats are underwater structures in which people can live for extended periods and carry out most of the Circadian rhythm, basic human functions of a 24-hour day, such as working, resting, eating, attending to personal hygiene, and ...

s developed and deployed by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

during the 1960s to prove the viability of saturation diving

Saturation diving is an ambient pressure diving technique which allows a diver to remain at working depth for extended periods during which the body tissues become solubility, saturated with metabolically inert gas from the breathing gas mixture ...

and humans living in isolation for extended periods of time. The knowledge gained from the SEALAB expeditions helped advance the science of deep sea diving and rescue and contributed to the understanding of the psychological and physiological strains humans can endure.

United States Navy Genesis Project

Preliminary research work was undertaken by George F. Bond, who named the project after theBook of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

, which prophesised humans would gain dominion over the oceans. Bond began investigations in 1957 to develop theories about saturation diving

Saturation diving is an ambient pressure diving technique which allows a diver to remain at working depth for extended periods during which the body tissues become solubility, saturated with metabolically inert gas from the breathing gas mixture ...

. Bond's team exposed rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include '' Neotoma'' (pack rats), '' Bandicota'' (bandicoo ...

s, goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a species of Caprinae, goat-antelope that is mostly kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the ...

s, monkey

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes. Thus monkeys, in that sense, co ...

s, and human beings to various gas mixtures at different pressures. By 1963 they had collected enough data to test the first SEALAB habitat.

At the time, Jacques Cousteau

Jacques-Yves Cousteau, (, also , ; 11 June 191025 June 1997) was a French naval officer, oceanographer, filmmaker and author. He co-invented the first successful open-circuit self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA), called the ...

and Edwin A. Link were pursuing privately funded saturation diving projects to study long-term underwater living. Link's efforts resulted in the first underwater habitat, occupied by aquanaut

An aquanaut is any person who remains underwater, breathing at the ambient pressure for long enough for the concentration of the inert components of the breathing gas dissolved in the body tissues to reach equilibrium, in a state known as sat ...

Robert Sténuit in the Mediterranean Sea at a depth of for one day on September 6, 1962. Cousteau's habitats included Conshelf I

Continental Shelf Station Two or Conshelf Two was an attempt at creating an environment in which people could live and work on the sea floor. It was the successor to Continental Shelf Station One (Conshelf One).

The alternate designation Preconti ...

, with a 2-person crew at a depth of near Marseilles, placed on September 14, 1962, and Conshelf II

Continental Shelf Station Two or Conshelf Two was an attempt at creating an environment in which people could live and work on the sea floor. It was the successor to Continental Shelf Station One (Conshelf One).

The alternate designation Precont ...

, placed in the Red Sea at depths of on June 15, 1963. Later that year, the Kennedy administration decided to open a new "race" frontier, directing the navy to begin the SEALAB program.

SEALAB I

SEALAB I was commanded by Captain Bond, who became known as "Papa Topside". SEALAB I proved that saturation diving in the open ocean was viable for extended periods. The experiment also offered information about habitat placement, habitat umbilicals, humidity, and helium speech descrambling.

SEALAB I was lowered off the coast of

SEALAB I was commanded by Captain Bond, who became known as "Papa Topside". SEALAB I proved that saturation diving in the open ocean was viable for extended periods. The experiment also offered information about habitat placement, habitat umbilicals, humidity, and helium speech descrambling.

SEALAB I was lowered off the coast of Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

on July 20, 1964 to a depth of below the ocean surface. It was constructed from two converted floats and held in place with axle

An axle or axletree is a central shaft for a rotation, rotating wheel and axle, wheel or gear. On wheeled vehicles, the axle may be fixed to the wheels, rotating with them, or fixed to the vehicle, with the wheels rotating around the axle. In ...

s from railroad car

A railroad car, railcar (American English, American and Canadian English), railway wagon, railway carriage, railway truck, railwagon, railcarriage or railtruck (British English and International Union of Railways, UIC), also called a tra ...

s. The experiment involved four divers (LCDR Robert Thompson, MC; Gunners Mate First Class Lester Anderson

Lester is an ancient Anglo-Saxon surname and given name.

People

Given name

* Lester Bangs (1948–1982), American music critic

* Lester Oliver Bankhead (1912–1997), American architect

* Lester W. Bentley (1908–1972), American artist from ...

, Chief Quartermaster Robert A. Barth, and Chief Hospital Corpsman Sanders Manning

Sanders may refer to:

People

Surname

* Sanders (surname)

Given name

*Sanders Anne Laubenthal (1943–2002), US writer

*Sanders Shiver (born 1955), former US National Football League player

Corporations

* Sanders Associates, part of BAE Sys ...

), who were to stay submerged for three weeks. The experiment was halted after 11 days due to an approaching tropical storm

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system with a low-pressure area, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depending on its lo ...

. SEALAB I demonstrated the same issues as Conshelf: high humidity, temperature control, and verbal communication in the helium atmosphere.

The astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a List of human spaceflight programs, human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spa ...

and second American to orbit the Earth, Scott Carpenter

Malcolm Scott Carpenter (May 1, 1925 – October 10, 2013) was an American naval officer and aviator, test pilot, aeronautical engineer, astronaut, and aquanaut. He was one of the Mercury Seven astronauts selected for NASA's Project Mercury ...

, was scheduled to be the fifth aquanaut in the habitat. Carpenter was trained by Robert A. Barth. Shortly before the experiment took place, Carpenter had a scooter accident on Bermuda and broke a few bones. The crash ruined his chances of making the dive.

SEALAB I is on display at the Man in the Sea Museum

The Man in the Sea Museum is a Military Diving Museum and is recognized as the oldest diving museum in the world. Located at 17314 Panama City Beach PKWY, FL. It has exhibits and documents related to the history of diving. Some of these exhibi ...

, in Panama City Beach, Florida

Panama City Beach is a resort town in the Florida Panhandle, and principal city of the Panama City Metropolitan Area. It is a popular vacation destination, especially among people in the Southern United States, and is located in the "Emerald C ...

, near where it was initially tested offshore before being deployed. It is on outdoor display. Its metal hull is largely intact, though the paint faded to a brick red over the years. The habitat's exterior was restored as part of its 50th anniversary, and now sports its original colors.

SEALAB II

SEALAB II was launched in 1965. It was nearly twice as large as SEALAB I with heating coils installed in the deck to ward off the constant helium-induced chill, and air conditioning to reduce the oppressive humidity. Facilities included hot showers, a built-in toilet, laboratory equipment, eleven viewing ports, two exits, and

SEALAB II was launched in 1965. It was nearly twice as large as SEALAB I with heating coils installed in the deck to ward off the constant helium-induced chill, and air conditioning to reduce the oppressive humidity. Facilities included hot showers, a built-in toilet, laboratory equipment, eleven viewing ports, two exits, and refrigeration

Refrigeration is any of various types of cooling of a space, substance, or system to lower and/or maintain its temperature below the ambient one (while the removed heat is ejected to a place of higher temperature).IIR International Dictionary of ...

. It was placed in the La Jolla Canyon off the coast of Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) is the center for oceanography and Earth science at the University of California, San Diego. Its main campus is located in La Jolla, with additional facilities in Point Loma.

Founded in 1903 and incorpo ...

at UC San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego in communications material, formerly and colloquially UCSD) is a public land-grant research university in San Diego, California, United States. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Sc ...

, in La Jolla, California

La Jolla ( , ) is a hilly, seaside neighborhood in San Diego, California, occupying of curving coastline along the Pacific Ocean. The population reported in the 2010 census was 46,781. The climate is mild, with an average daily temperature o ...

, at a depth of . On August 28, 1965, the first of three teams of divers moved into what became known as the "Tilton Hilton" (Tiltin' Hilton, because of the slope of the landing site). The support ship ''Berkone'' hovered on the surface above, within sight of Scripps Pier. The helium atmosphere conducted heat away from the divers’ bodies so quickly temperatures were raised to to ward off chill.

Each team spent 15 days in the habitat, but aquanaut/former astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a List of human spaceflight programs, human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spa ...

Scott Carpenter

Malcolm Scott Carpenter (May 1, 1925 – October 10, 2013) was an American naval officer and aviator, test pilot, aeronautical engineer, astronaut, and aquanaut. He was one of the Mercury Seven astronauts selected for NASA's Project Mercury ...

remained below for a record 30 days. In addition to physiological testing, the 28 divers tested new tools, methods of salvage, and an electrically heated drysuit. They were aided by a bottlenose dolphin

The bottlenose dolphin is a toothed whale in the genus ''Tursiops''. They are common, cosmopolitan members of the family Delphinidae, the family of oceanic dolphins. Molecular studies show the genus contains three species: the common bot ...

named Tuffy from the United States Navy Marine Mammal Program. Aquanauts and Navy trainers attempted, with mixed results, to teach Tuffy to ferry supplies from the surface to SEALAB or from one diver to another, and to come to the rescue of an aquanaut in distress. When the SEALAB II mission ended on 10 October 1965, there were plans for Tuffy also to take part in SEALAB III.Hellwarthp. 173. A sidenote from SEALAB II was a congratulatory

telephone

A telephone, colloquially referred to as a phone, is a telecommunications device that enables two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most ...

call that was arranged for Carpenter and President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

. Carpenter was calling from a decompression chamber

A diving chamber is a vessel for human occupation, which may have an entrance that can be sealed to hold an internal pressure significantly higher than ambient pressure, a pressurised gas system to control the internal pressure, and a supply of ...

with helium

Helium (from ) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, non-toxic, inert gas, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. Its boiling point is ...

gas replacing nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

, so Carpenter sounded unintelligible to operators. The tape of the call circulated for years among Navy divers before it was aired on National Public Radio

National Public Radio (NPR) is an American public broadcasting organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It serves as a national Radio syndication, syndicator to a network of more ...

in 1999.

In 2002, a group of researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography's High Performance Wireless Research and Education Network boarded the and used a Scorpio ROV

The Scorpio (Submersible Craft for Ocean Repair, Position, Inspection and Observation) is a brand of underwater submersible Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) manufactured by Perry Tritech used by sub-sea industries such as the oil industry for gen ...

to find the site of the SEALAB habitat. This expedition was the first return to the site since the habitat was moved.

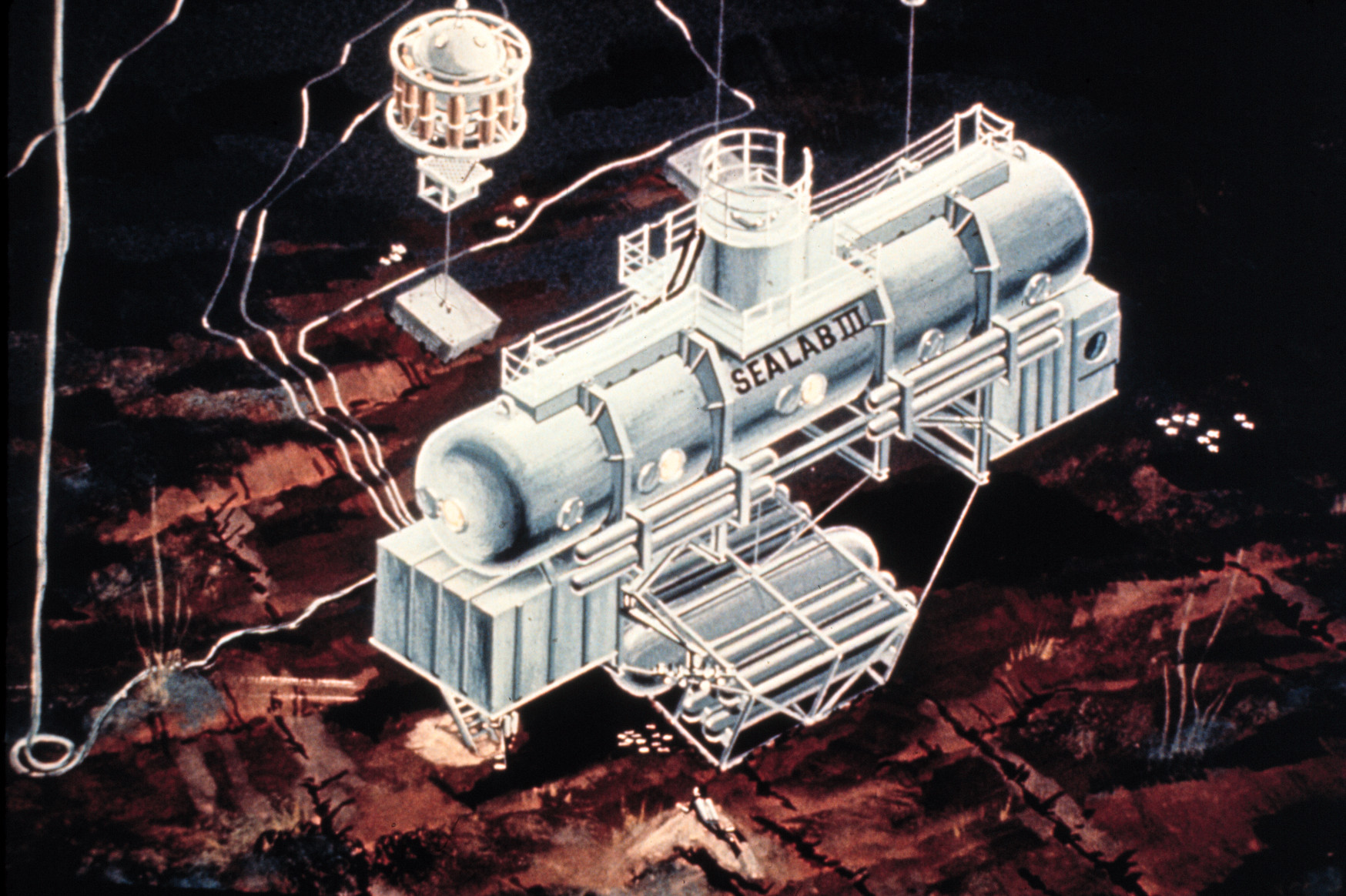

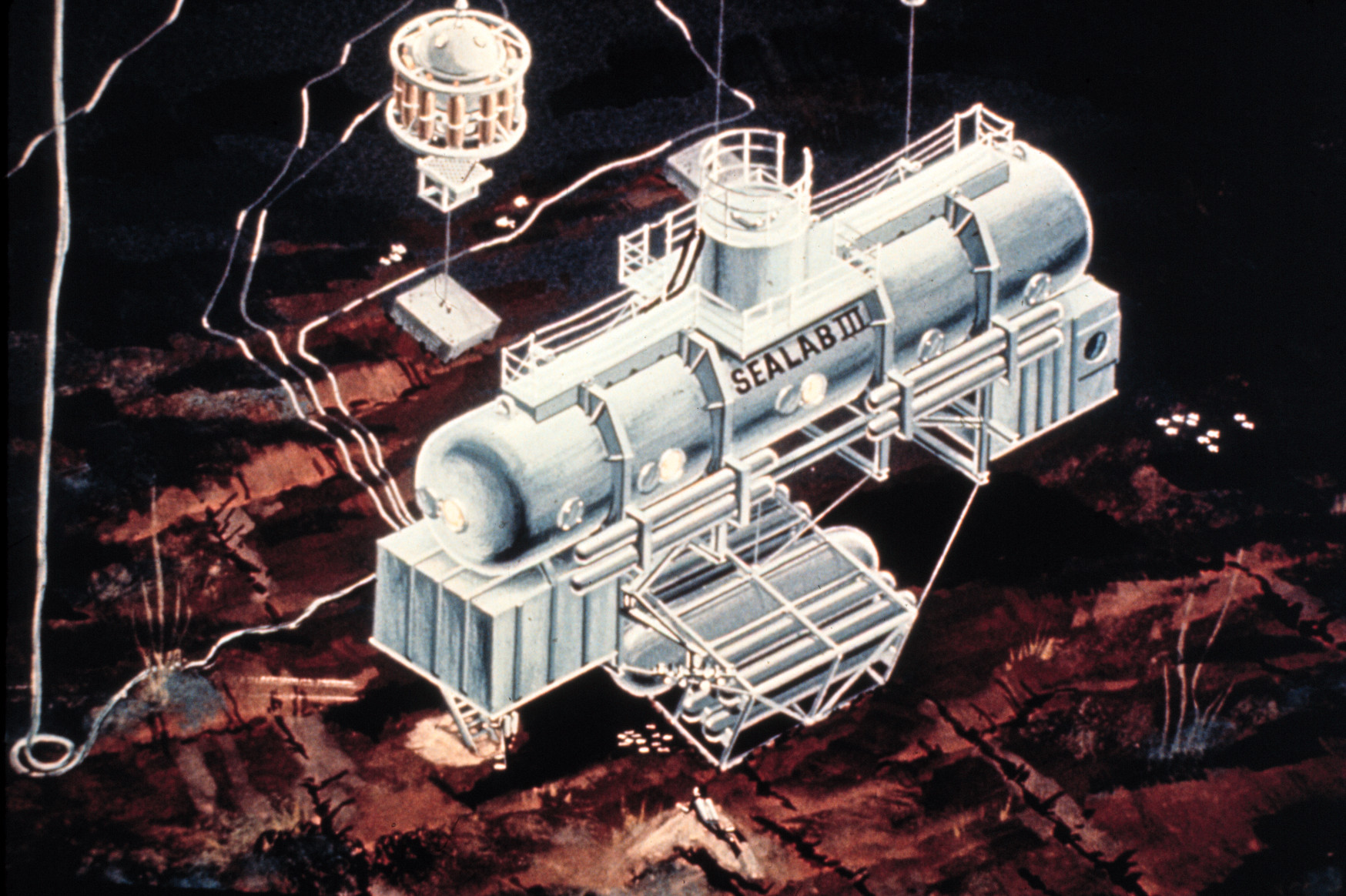

SEALAB III

With naval research funding constrained byVietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

combat requirements, it was four years later before SEALAB III used the refurbished SEALAB II habitat placed in water three times deeper. Five teams of nine divers were scheduled to spend 12 days each in the habitat, testing new salvage techniques and conducting oceanographic

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of top ...

and fishery

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life or, more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a., fishing grounds). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish far ...

studies. Preparations for such a deep dive were extensive. In addition to many biomedical

Biomedicine (also referred to as Western medicine, mainstream medicine or conventional medicine)

studies, work-up dives were conducted at the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit at the Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, Navy Yard. These “dives” were not done in the open sea, but in a special hyperbaric chamber

A diving chamber is a vessel for human occupation, which may have an entrance that can be sealed to hold an internal pressure significantly higher than ambient pressure, a pressurised gas system to control the internal pressure, and a supply of ...

that could recreate the pressures at depths as great as of sea water.

According to John Piña Craven, the U.S. Navy's head of the Deep Submergence Systems Project of which SEALAB was a part, SEALAB III "was plagued with strange failures at the very start of operations". USS ''Elk River'' (IX-509) was specially fitted as a SEALAB operations support ship to replace ''Berkone''; but the project was 18 months late and three million dollars over budget when SEALAB III was lowered to off

According to John Piña Craven, the U.S. Navy's head of the Deep Submergence Systems Project of which SEALAB was a part, SEALAB III "was plagued with strange failures at the very start of operations". USS ''Elk River'' (IX-509) was specially fitted as a SEALAB operations support ship to replace ''Berkone''; but the project was 18 months late and three million dollars over budget when SEALAB III was lowered to off San Clemente Island

San Clemente Island (Tongva: ''Kinkipar''; Spanish: ''Isla de San Clemente'') is the southernmost of the Channel Islands of California. It is owned and operated by the United States Navy, and is a part of Los Angeles County. It is administer ...

, California, on 15 February 1969. SEALAB team members were tense and frustrated by these delays, and began taking risks to make things work. When a poorly sized neoprene seal caused helium to leak from the habitat at an unacceptable rate, four divers volunteered to repair the leak in place rather than lifting the habitat to the surface. Their first attempt was unsuccessful, and the divers had been awake for twenty hours using amphetamine

Amphetamine (contracted from Alpha and beta carbon, alpha-methylphenethylamine, methylphenethylamine) is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, an ...

s to stay alert for a second attempt, during which aquanaut

An aquanaut is any person who remains underwater, breathing at the ambient pressure for long enough for the concentration of the inert components of the breathing gas dissolved in the body tissues to reach equilibrium, in a state known as sat ...

Berry L. Cannon died. A U.S. Navy Board of Inquiry found that Cannon's rebreather

A rebreather is a breathing apparatus that absorbs the carbon dioxide of a user's exhaled breath to permit the rebreathing (recycling) of the substantial unused oxygen content, and unused inert content when present, of each breath. Oxygen is a ...

was missing baralyme, the chemical necessary to remove carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

. Surgeon commander John Rawlins, a Royal Navy medical officer assigned to the project, also suggested that hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

during the dive was a contributing factor to the problem not being recognized by the diver.

According to Craven, while the other divers were undergoing the week-long decompression, repeated attempts were made to sabotage their air supply by someone aboard the command barge. Eventually, a guard was posted on the decompression chamber and the men were recovered safely. A potentially unstable suspect was identified by the staff psychiatrist, but the culprit was never prosecuted. Craven suggests this may have been done to spare the Navy bad press so soon after the incident.

After reinvestigating Cannon's death, ocean engineer Kevin Hardy concluded in a 2024 article that "There is greater evidence that Berry Cannon died from electrocution

Electrocution is death or severe injury caused by electric shock from electric current passing through the body. The word is derived from "electro" and "execution", but it is also used for accidental death.

The term "electrocution" was coined ...

than poisoning."

The SEALAB program came to a halt, and although the SEALAB III habitat was retrieved, it was eventually scrapped. Aspects of the research continued, but no new habitats were built.

NCEL (now a part of Naval Facilities Engineering Service Center) of Port Hueneme, California

Port Hueneme ( ; Chumashan languages, Chumash: ''Wene Me'') is a small beach city in Ventura County, California, surrounded by the city of Oxnard, California, Oxnard and the Santa Barbara Channel. Both the Port of Hueneme and Naval Base Ventura ...

, was responsible for the handling of several contracts involving life support systems used on SEALAB III.

A model of SEALAB III can be found at the Man in the Sea Museum

The Man in the Sea Museum is a Military Diving Museum and is recognized as the oldest diving museum in the world. Located at 17314 Panama City Beach PKWY, FL. It has exhibits and documents related to the history of diving. Some of these exhibi ...

in Panama City Beach, Florida

Panama City Beach is a resort town in the Florida Panhandle, and principal city of the Panama City Metropolitan Area. It is a popular vacation destination, especially among people in the Southern United States, and is located in the "Emerald C ...

.

See also

* * * *References

*This page incorporates text in thepublic domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no Exclusive exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly Waiver, waived, or may be inapplicable. Because no one holds ...

from thOffice of Naval Research

Bibliography

* * * * * (For children.)External links

*US Naval Undersea Museu(One screen shot o

current habitat

* * * {{Authority control United States Navy in the 20th century Underwater habitats Scott Carpenter