Ross expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ross expedition was a voyage of scientific

The Ross expedition was a voyage of scientific

In September 1839, ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' departed Chatham in Kent, arriving at

In September 1839, ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' departed Chatham in Kent, arriving at

File:Flora Antarctica title page.jpg, Title page of '' Flora Antarctica'', 1844–1846

File:Flora Antarctica Plate CXXIV.jpg, '' Fagus betuloides'' (''Flora Antarctica'', Plate CXXIV)

File:Flora Antarctica Nitophyllum smithi.jpg, The

Cool Antarctica: Erebus and Terror

Encyclopedia of Earth: Three National Expeditions to Antarctica

{{Polar exploration , state=collapsed Antarctic expeditions Expeditions from Great Britain 1830s in Antarctica 1840s in Antarctica Flora of the Antarctic 1830s in science 1840s in science Scientific expeditions Botanists active in New Zealand Botanists active in South America History of the Ross Dependency

The Ross expedition was a voyage of scientific

The Ross expedition was a voyage of scientific exploration

Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some Expectation (epistemic), expectation of Discovery (observation), discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organis ...

of the Antarctic

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is antipodes, diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antar ...

in 1839 to 1843, led by James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer of both the northern and southern polar regions. In the Arctic, he participated in two expeditions led by his uncle, Sir John Ross, John ...

, with two unusually strong warships, HMS ''Erebus'' and HMS ''Terror''. It explored what is now called the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

and discovered the Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between high ...

. On the expedition, Ross discovered the Transantarctic Mountains

The Transantarctic Mountains (abbreviated TAM) comprise a mountain range of uplifted rock (primarily sedimentary) in Antarctica which extends, with some interruptions, across the continent from Cape Adare in northern Victoria Land to Coats L ...

and the volcanoes Mount Erebus and Mount Terror, named after each ship. The young botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

made his name on the expedition.

The expedition confirmed the existence of the continent of Antarctica, inferred the position of the South Magnetic Pole and made substantial observations of the zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

and botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

of the region, resulting in a monograph on the zoology and a series of four detailed monographs by Hooker on the botany, collectively called '' Flora Antarctica'', published in parts between 1843 and 1859. Among the expedition's biological discoveries was the Ross seal, a species confined to the pack ice of Antarctica. The expedition was also the last major voyage of exploration made wholly under sail

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may b ...

.

Expedition

Background

In 1838, theBritish Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

(BA) proposed an expedition to carry out magnetic

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, m ...

measurements in the Antarctic. Sir James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer of both the northern and southern polar regions. In the Arctic, he participated in two expeditions led by his uncle, Sir John Ross, John ...

was chosen to lead the expedition after previous experience working on the British Magnetic Survey from 1834 onwards, working with prominent physicists and geologists such as Humphrey Lloyd, Sir Edward Sabine, John Phillips and Robert Were Fox. Ross had made many previous expeditions to the Arctic, including experience as captain.

People

Ross, a captain of theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, commanded HMS ''Erebus''. Its sister ship, HMS ''Terror'', was commanded by Ross' close friend, Captain Francis Crozier.

The botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

, then aged 23 and the youngest person on the expedition, was assistant-surgeon to Robert McCormick, and responsible for collecting zoological

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

and geological

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth s ...

specimens. Hooker later became one of England's greatest botanists; he was a close friend of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

and became director of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew for twenty years. McCormick had been ship's surgeon for the second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'' under Captain Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy, politician and scientist who served as the second governor of New Zealand between 1843 and 1845. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of ...

, along with Darwin as gentleman naturalist.

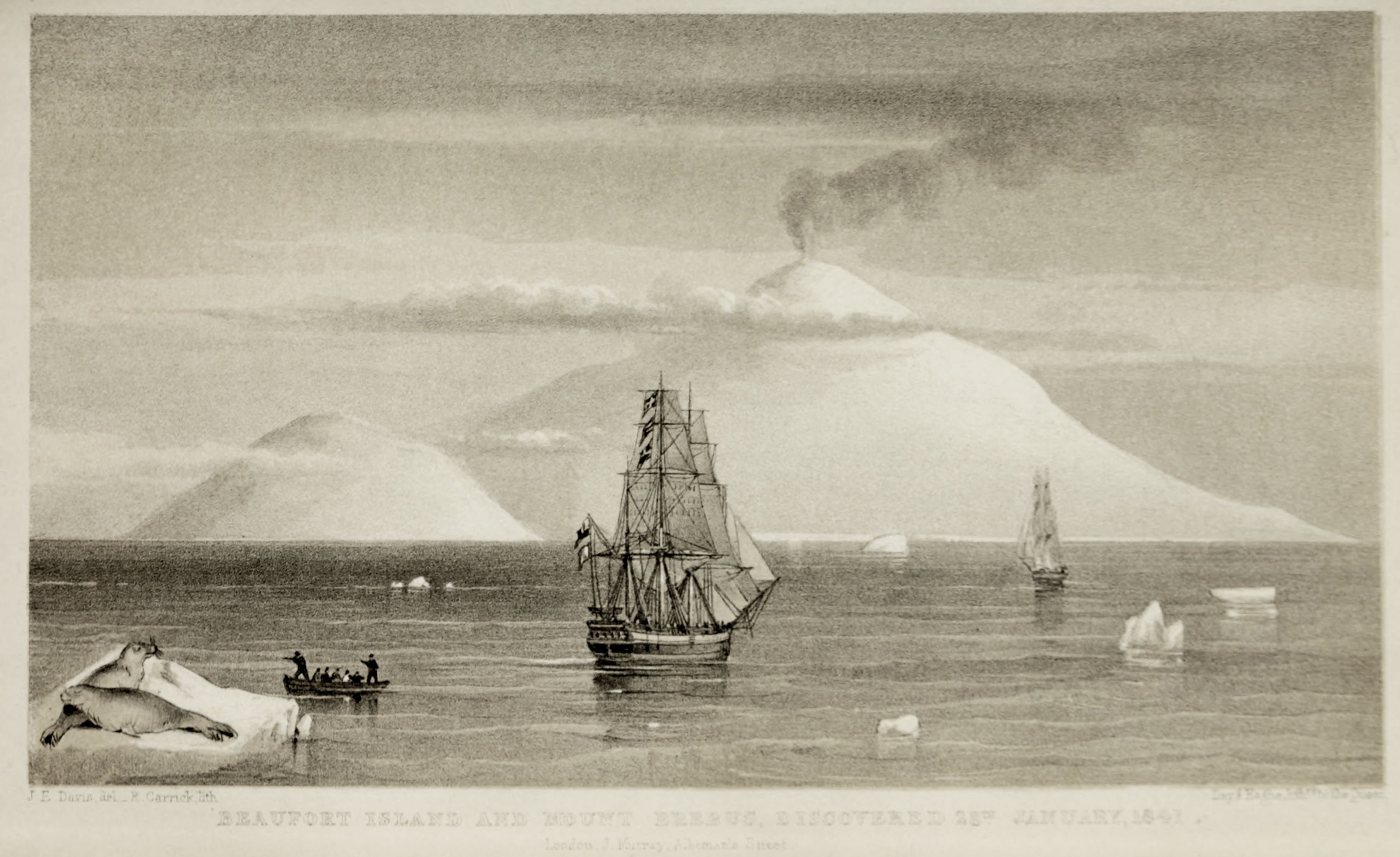

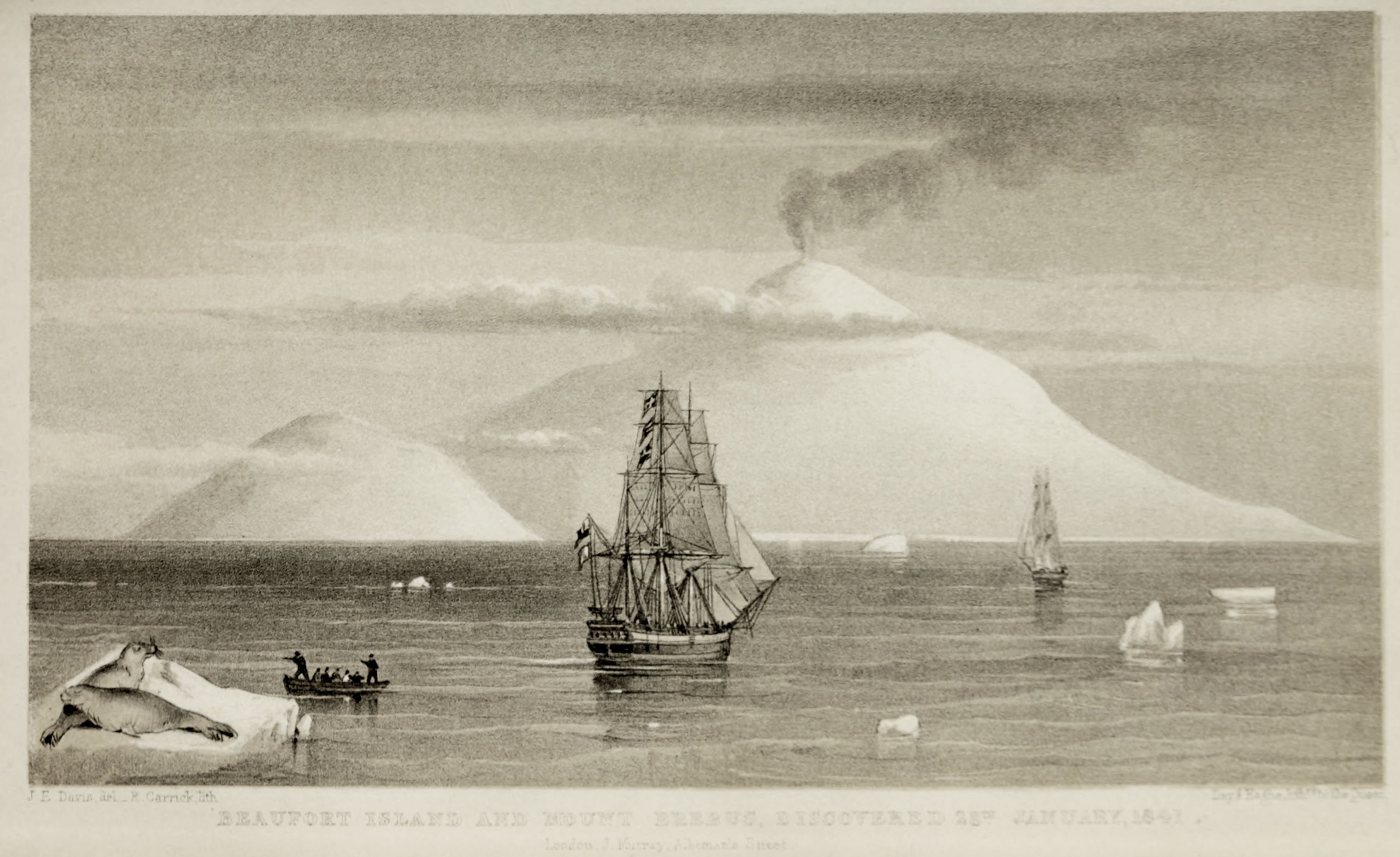

The second master on ''Terror'' was John E. Davis who was responsible for much of the surveying and chart production, as well as producing many illustrations of the voyage. He had been on the ''Beagle'' surveying the coasts of Bolivia, Peru and Chile. Another Arctic veteran was Thomas Abernethy, another friend of Ross, who joined the new expedition as a gunner.

Ships

HMS ''Erebus'' and HMS ''Terror'', the ships servicing the Ross expedition, were two unusually strong warships. Both were bomb ships, named and equipped to fire heavy mortar bombs at a high angle over defences, and were accordingly heavily built to withstand the substantial recoil of these three-ton weapons. Their solid construction ideally suited them for use in dangerous sea ice that might crush other ships. The 372-ton ''Erebus'' had been armed with two mortars – one and one – and ten guns.Voyage

In September 1839, ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' departed Chatham in Kent, arriving at

In September 1839, ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' departed Chatham in Kent, arriving at Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

(then known as Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

) in August 1840. On 21 November 1840 they departed for Antarctica. In January 1841, the ships landed on Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region in eastern Antarctica which fronts the western side of the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf, extending southward from about 70°30'S to 78th parallel south, 78°00'S, and westward from the Ross Sea to the edge of the Ant ...

and proceeded to name areas of the landscape after British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

politicians, scientists and acquaintances. Mount Erebus, on Ross Island

Ross Island is an island in Antarctica lying on the east side of McMurdo Sound and extending from Cape Bird in the north to Cape Armitage in the south, and a similar distance from Cape Royds in the west to Cape Crozier in the east.

The isl ...

, was named after one ship and Mount Terror after the other. McMurdo Bay (now known as McMurdo Sound) was named after Archibald McMurdo, senior lieutenant of ''Terror''.

Reaching latitude 76° south on 28 January 1841, the explorers spied

...a low white line extending from its eastern extreme point as far as the eye could discern... It presented an extraordinary appearance, gradually increasing in height, as we got nearer to it, and proving at length to be a perpendicular cliff of ice, between one hundred and fifty and two hundred feet above the level of the sea, perfectly flat and level at the top, and without any fissures or promontories on its even seaward face.Ross called this the "Great Ice Barrier", now known as the

Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between high ...

, which they were unable to penetrate, although they followed it eastward until the lateness of the season compelled them to return to Tasmania. The following summer, 1841–42, Ross continued to follow the ice shelf eastward. Both ships stayed at Port Louis

Port Louis (, ; or , ) is the capital and most populous city of Mauritius, mainly located in the Port Louis District, with a small western part in the Black River District. Port Louis is the country's financial and political centre. It is admi ...

in the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; ), commonly referred to as The Falklands, is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and from Cape Dub ...

for the winter, returning in September 1842 to explore the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

, where they conducted studies in magnetism, and gathered oceanographic

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of top ...

data and collections of botanical

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

and ornithological specimens.

The expedition arrived back in England on 4 September 1843, having confirmed the existence of the southern continent and charted a large part of its coastline. It was the last major voyage of exploration made wholly under sail

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may b ...

. Both ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' would later be fitted with steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

s and used for Franklin's lost expedition of 1845–1848, in which both ships (and all crew) would ultimately be lost; their ship-wrecks have now been found.

Discoveries

Geography

Ross discovered the "enormous" Ross Ice Shelf, correctly observing that it was the source of the tabular icebergs seen in theSouthern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

, and helping to found the science of glaciology

Glaciology (; ) is the scientific study of glaciers, or, more generally, ice and natural phenomena that involve ice.

Glaciology is an interdisciplinary Earth science that integrates geophysics, geology, physical geography, geomorphology, clim ...

. He identified the Transantarctic Mountains

The Transantarctic Mountains (abbreviated TAM) comprise a mountain range of uplifted rock (primarily sedimentary) in Antarctica which extends, with some interruptions, across the continent from Cape Adare in northern Victoria Land to Coats L ...

and the volcanoes Erebus and Terror, named after his ships.

Magnetism

The main purpose of the Ross expedition was to find the position of the South Magnetic Pole, by making observations of the Earth's magnetism in the Southern hemisphere. Ross did not reach the Pole, but did infer its position. The expedition made the first "definitive" charts ofmagnetic declination

Magnetic declination (also called magnetic variation) is the angle between magnetic north and true north at a particular location on the Earth's surface. The angle can change over time due to polar wandering.

Magnetic north is the direction th ...

, magnetic dip

Magnetic dip, dip angle, or magnetic inclination is the angle made with the horizontal by Earth's magnetic field, Earth's magnetic field lines. This angle varies at different points on Earth's surface. Positive values of inclination indicate t ...

and magnetic intensity, in place of the less accurate charts made by the earlier expeditions of Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes (April 3, 1798 – February 8, 1877) was an American naval officer, ship's captain, and List of explorers, explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842).

During the American Civil War between 1861 and 1865 ...

and Dumont d'Urville

Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville (; 23 May 1790 – 8 May 1842) was a French explorer and naval officer who explored the south and western Pacific, Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica. As a botanist and cartographer, he gave his name ...

.

Zoology

The expedition's zoological discoveries included a collection of birds. They were described and illustrated byGeorge Robert Gray

George Robert Gray (8 July 1808 – 6 May 1872) was an English zoology, zoologist and author, and head of the Ornithology, ornithological section of the British Museum, now the Natural History Museum, London, Natural History Museum, London f ...

and Richard Bowdler Sharpe

Richard Bowdler Sharpe (22 November 1847 – 25 December 1909) was an English people, English zoologist and ornithology, ornithologist who worked as curator of the bird collection at the British Museum of natural history. In the course of his car ...

in ''The Zoology of the Voyage of HMS Erebus & HMS Terror''.

The expedition was the first to describe the Ross seal, which it found in the pack ice, to which the species is confined.

Botany

The expedition's botanical discoveries were documented in Joseph Dalton Hooker's four-part '' Flora Antarctica'' (1843–1859). It totalled six volumes (parts III and IV each being in two volumes), covered about 3000 species, and contained 530 plates figuring in all 1095 of the species described. It was throughout "splendidly" illustrated byWalter Hood Fitch

Walter Hood Fitch (28 February 1817 – 14 January 1892) was a botanical illustrator, born in Glasgow, Scotland, who executed some 10,000 drawings for various publications.

His work in colour lithograph, including 2700 illustrations for ''C ...

. The parts were:

* Part I '' Botany of Lord Auckland's Group and Campbell's Island'' (1844–1845)

* Part II '' Botany of Fuegia, the Falklands, Kerguelen's Land, Etc.'' (1845–1847)

* Part III '' Flora Novae-Zelandiae'' (1851–1853) (2 volumes)

* Part IV '' Flora Tasmaniae'' (1853–1859) (2 volumes)

Hooker gave Charles Darwin a copy of the first part of the ''Flora''; Darwin thanked him, and agreed in November 1845 that the geographical distribution of organisms would be "the key which will unlock the mystery of species".

red alga

Red algae, or Rhodophyta (, ; ), make up one of the oldest groups of eukaryotic algae. The Rhodophyta comprises one of the largest Phylum, phyla of algae, containing over 7,000 recognized species within over 900 Genus, genera amidst ongoing taxon ...

'' Nitophyllum smithi''

Influence

In 1912, the Norwegian explorerRoald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegians, Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Am ...

wrote of the Ross expedition that "Few people of the present day are capable of rightly appreciating this heroic deed, this brilliant proof of human courage and energy. With two ponderous craft – regular "tubs" according to our ideas – these men sailed right into the heart of the pack ce which all previous explorers had regarded as certain death ... These men were heroes – heroes in the highest sense of the word."

Hooker's ''Flora Antarctica'' remains important; in 2013 W. H. Walton in his ''Antarctica: Global Science from a Frozen Continent'' describes it as "a major reference to this day", encompassing as it does "all the plants he found both in the Antarctic and on the sub-Antarctic islands", surviving better than Ross's deep-sea soundings which were made with "inadequate equipment".

References

External links

Cool Antarctica: Erebus and Terror

Encyclopedia of Earth: Three National Expeditions to Antarctica

{{Polar exploration , state=collapsed Antarctic expeditions Expeditions from Great Britain 1830s in Antarctica 1840s in Antarctica Flora of the Antarctic 1830s in science 1840s in science Scientific expeditions Botanists active in New Zealand Botanists active in South America History of the Ross Dependency