Robert Venables on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Venables (ca. 1613–1687), was an English soldier from Cheshire, who fought for

Venables left Ireland in May 1654 and was appointed commander of land forces for the

Venables left Ireland in May 1654 and was appointed commander of land forces for the  Few veterans of the New Model were willing to serve in an area notorious for disease and on an expedition with such vague objectives, so many of the 2,500 troops brought from England were untrained, as well as poorly equipped. They reached

Few veterans of the New Model were willing to serve in an area notorious for disease and on an expedition with such vague objectives, so many of the 2,500 troops brought from England were untrained, as well as poorly equipped. They reached

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

in the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 B ...

, and captured Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

in 1655.

When the Anglo-Spanish War began in 1654, he was made joint commander of an expedition against Spanish possessions in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

, known as the Western Design

The Western Design is the term commonly used for an English expedition against the Spanish West Indies during the 1654 to 1660 Anglo-Spanish War.

Part of an ambitious plan by Oliver Cromwell to end Spanish dominance in the Americas, the force ...

. Although he captured Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, which remained a British colony for over 300 years, the project was considered a failure, ending his military career.

Appointed Governor of Chester shortly before The Restoration of Charles II in 1660, his religious views made him unacceptable to the new regime. He returned to private life and in 1662 published a treatise on fishing, ''The Experienced Angler'', which went through five editions in his lifetime. Arrested but released without charge after the Farnley Wood Plot

The Farnley Wood Plot was a conspiracy in Yorkshire, England in October 1663. Intended as a major rising to overturn the return to monarchy in 1660, it was undermined by informers, and came to nothing.

The major plotters were Joshua Greathead a ...

in 1663, in 1668 he purchased an estate at Wincham, Cheshire, where he lived quietly until his death in 1687.

Personal details

Robert Venables was the son of Robert Venables () ofAntrobus, Cheshire

Antrobus is a civil parish and village in Cheshire, England, immediately to the south of Warrington. It lies within the unitary authority of Cheshire West and Chester, and has a population of 832, reducing to 791 at the 2011 Census. The parish i ...

and Ellen Simcox (1577–1658), daughter of Richard Simcox of Rudheath

Rudheath is a village and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire West and Chester and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, in the north west of England, approximately 2 miles east of Northwich. The population of the civil parish as tak ...

; he seems to have had at least one sister, Elizabeth (1609–1683), but details are unclear. The Venables were a cadet branch

In history and heraldry, a cadet branch consists of the male-line descendants of a monarch's or patriarch's younger sons ( cadets). In the ruling dynasties and noble families of much of Europe and Asia, the family's major assets— realm, tit ...

of a family that could trace their ancestry back to the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Con ...

, and were classed as members of the minor gentry. His father had interests in the Cheshire salt mine industry and was part of a local Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

network; Robert's godfather was the preacher Richard Mather

Richard Mather (1596 – 22 April 1669) was a New England Puritan minister in colonial Boston. He was father to Increase Mather and grandfather to Cotton Mather, both celebrated Boston theologians.

Biography

Mather was born in Lowton in the p ...

, grandfather of Cotton Mather.

His first wife was Elizabeth Rudyard; the date of their marriage is unknown, but appears to have been sometime in the mid 1630s, and she died before 1649. Only two of their five children survived into adulthood; Thomas (1640–1659), and Frances (1638–1692).

Shortly before Venables went to Ireland in 1649, he became engaged to Elizabeth Lee (1614–1689), mother of seven and widow of Thomas Lee of Darnhall, Cheshire. They finally married on his return in 1654; at the same time, her son Thomas married his daughter Frances, while his son, also Thomas, married her daughter Elizabeth, breaking a prior engagement to another girl. Their marriage was not a success; she allegedly "disliked his politics, disdained his religion, and disapproved of his manners."

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

Almost nothing is known of his career prior to the beginning of theFirst English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

in August 1642, when he raised a company for the Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

garrison. In December, he was captured in a skirmish near Westhoughton, Lancashire but quickly released. The Venables family had long-standing connections to the Breretons, one of the most powerful families in Cheshire, and for the rest of the war he served under Sir William Brereton, the senior local Parliamentarian. Despite lacking military experience, Brereton proved an energetic and resolute commander, winning minor victories in March 1643 at Middlewich

Middlewich is a town in the unitary authority of Cheshire East and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England, east of Chester, east of Winsford, southeast of Northwich and northwest of Sandbach. The population at the 2011 Census was 13,595 ...

and Hopton Heath.

Brereton established his headquarters at Nantwich

Nantwich ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. It has among the highest concentrations of listed buildings in England, with notably good examples of Tudor and Georgian architecture. ...

and quickly attained superiority over Arthur Capell

Arthur Capell (28 March 1902 – 10 August 1986) was an Australian linguist, who made major contributions to the study of Australian languages, Austronesian languages and Papuan languages.

Early life

Capell was born in Newtown, New South Wales ...

, Royalist commander in Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

, Cheshire, and North Wales

North Wales ( cy, Gogledd Cymru) is a region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders Mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, with Snowdonia N ...

. From August to September 1643, Venables was based at Cholmondeley, which he used as a base for attacking nearby Royalist garrisons. These supported the blockade of Chester, a town essential for funnelling men and material from Royalist areas in Ireland and North Wales. Their success led to Capell's replacement by Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

in October 1643.

Byron assembled an army of over 5,000, many of whom were veterans from the war in Ireland, and defeated the Parliamentarians at the Second Battle of Middlewich

The Second Battle of Middlewich took place on 26 December 1643 near Middlewich in Cheshire during the First English Civil War. A Cavalier, Royalist force under John Byron, 1st Baron Byron, Lord Byron defeated a Roundhead, Parliamentarian army co ...

in December. Brereton appealed to Sir Thomas Fairfax

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and Parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War. An adept and talented command ...

for support, and their combined force routed the Royalists at Nantwich

Nantwich ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. It has among the highest concentrations of listed buildings in England, with notably good examples of Tudor and Georgian architecture. ...

in January 1644. Having lost over 1,500 men and most of his artillery, Byron retreated into Chester, and Venables spent much of the next two years as governor of Tarvin

Tarvin is a village in the unitary authority of Cheshire West and Chester and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. It had a population of 2,693 people at the 2001 UK census, rising to 2,728 at the 2011 Census, and the ward covers about .

...

. When Chester finally surrendered in February 1646, Brereton recommended him as governor, but instead the position went to Irishman Michael Jones. Now a Lieutenant Colonel, Venables spent the next few months reducing Royalist garrisons in North Wales before the war ended in June.

Despite victory, the cost of the war, a poor 1646 harvest, and a recurrence of the plague left Parliament unable to pay their soldiers. In summer 1647, the garrison of Nantwich mutinied; Venables restored order, and was made governor of Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

in January 1648, a position he held during the Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February to August 1648 in Kingdom of England, England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 1641� ...

. Promoted colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

in 1649, he raised a regiment of Cheshire veterans sent to reinforce Michael Jones, newly appointed Parliamentarian Governor of Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 c ...

. They arrived in time for the Battle of Rathmines

The Battle of Rathmines was fought on 2 August 1649, near the modern Dublin suburb of Rathmines, during the Irish Confederate Wars, an associated conflict of 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It has been described as the 'decisive battl ...

on 2 August, a decisive victory over a Royalist/ Confederate force under the Marquess of Ormond.

On 15 August, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

arrived with an expeditionary force of 12,000 to begin the conquest of Ireland, and Venables took part in the storming of Drogheda. Along with Michael Jones' brother Sir Theophilus, a detachment led by Venables joined forces with Sir Charles Coote in Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

. Over the next twelve months, the three conducted a campaign to subdue the north, including the battles of Lisnagarvey

Lisnagarvey or Lisnagarvy () is a townland in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. Lisnagarvey is also an Anglicisation of the original name of Lisburn.

The townland was named after an earthen ringfort (''lios''), which was in the area of present-day ...

and Scariffhollis. Charlemont, the last Confederate stronghold in Ulster, surrendered in August 1650, and their only significant field army dissolved in December when the Marquess of Clanricarde

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman w ...

went into exile.

Venables spent the next two years fighting an often brutal counter insurgency war in north Connaught

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Delbhn ...

and south-west Ulster; his troops were always in arrears with their pay, and on several occasions he and Jones resorted to confiscating taxes collected for Dublin. In 1653, he helped implement the draconian 1652 Act of Settlement, while resisting attempts to impose Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

in Ulster; like many in the New Model, he was a religious Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

, who opposed any state-ordered church.

The Western Design

Venables left Ireland in May 1654 and was appointed commander of land forces for the

Venables left Ireland in May 1654 and was appointed commander of land forces for the Western Design

The Western Design is the term commonly used for an English expedition against the Spanish West Indies during the 1654 to 1660 Anglo-Spanish War.

Part of an ambitious plan by Oliver Cromwell to end Spanish dominance in the Americas, the force ...

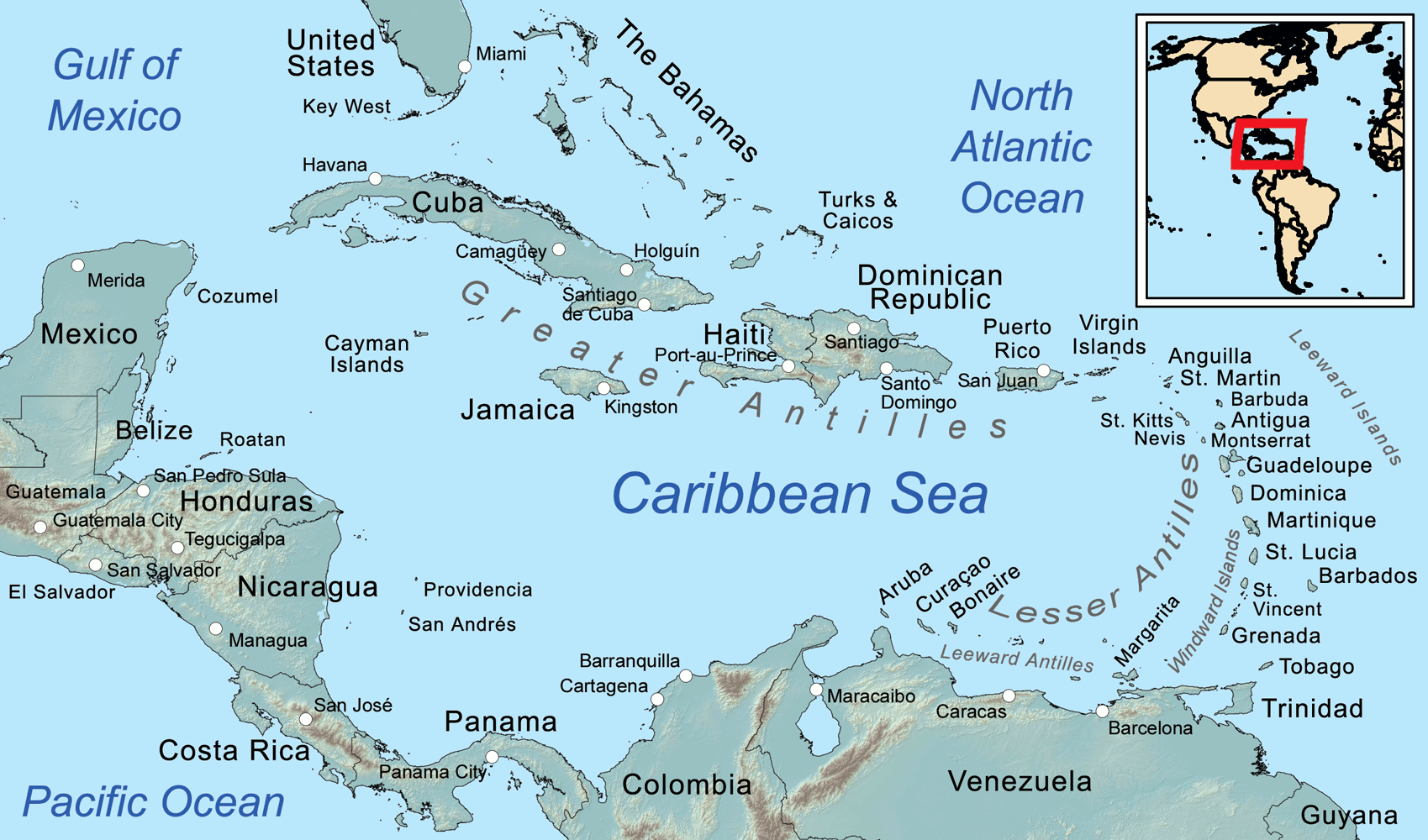

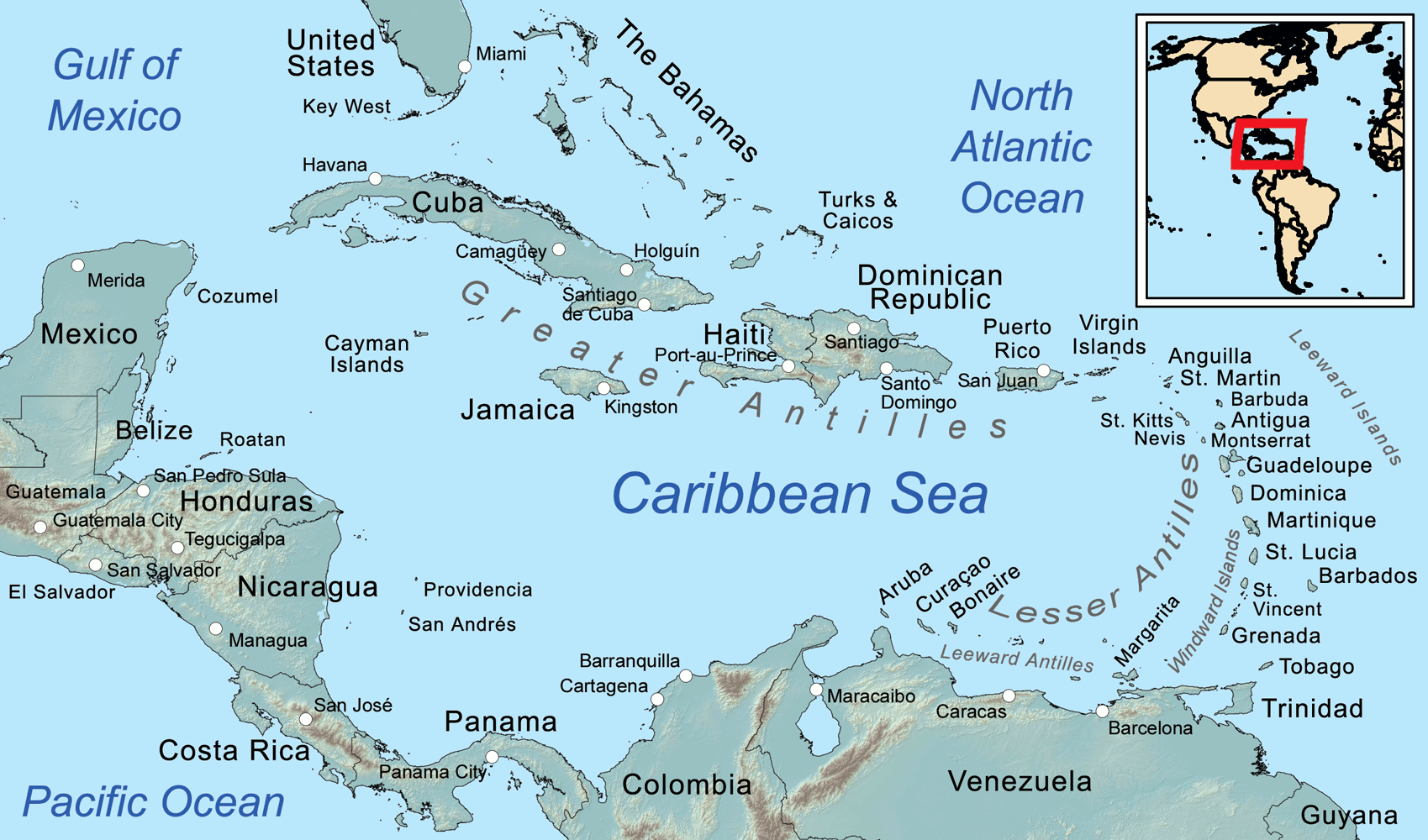

, an attack on the Spanish West Indies

The Spanish West Indies or the Spanish Antilles (also known as "Las Antillas Occidentales" or simply "Las Antillas Españolas" in Spanish) were Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. In terms of governance of the Spanish Empire, The Indies was the d ...

intended to secure a permanent base in the Caribbean. It was largely driven by Cromwell, who had been involved in the Providence Island Company

The Providence Company or Providence Island Company was an English chartered company founded in 1629 by a group of Puritans including Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick in order to establish the Providence Island colony on Providence Island and M ...

, a Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

colony established off the coast of Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

in 1630 and abandoned in 1641. Planning was based on input from Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of th ...

, a former missionary regarded as an expert on the region who claimed the Spanish colonies of Hispaniola and Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

were weakly defended, advice which proved incorrect.

Given the distances involved, Venables insisted on flexibility of objectives; Cromwell agreed and his instructions were simply "to gain an interest in that part of the West Indies in possession of the Spaniards". Leadership was shared with Admiral William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

, who commanded the fleet, and two civilian commissioners, Edward Winslow

Edward Winslow (18 October 15958 May 1655) was a Separatist and New England political leader who traveled on the ''Mayflower'' in 1620. He was one of several senior leaders on the ship and also later at Plymouth Colony. Both Edward Winslow and ...

, former Governor of Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the passengers on the ...

, and Gregory Butler, who were to supervise colonisation of the captured lands. The fleet departed Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

at the end of December 1654, with Venables accompanied by his new wife Elizabeth.

Few veterans of the New Model were willing to serve in an area notorious for disease and on an expedition with such vague objectives, so many of the 2,500 troops brought from England were untrained, as well as poorly equipped. They reached

Few veterans of the New Model were willing to serve in an area notorious for disease and on an expedition with such vague objectives, so many of the 2,500 troops brought from England were untrained, as well as poorly equipped. They reached Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate) ...

at the end of January and spent the next two months recruiting another 3,500 from indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

on the island and elsewhere in the region. The Spanish had been aware of the project for some time and this additional delay allowed them to send reinforcements to Hispaniola; the plan assumed secrecy and superior English forces, neither of which were true.

The attack on Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

in April was disastrous; the troops raised in Barbados proved little more than a rabble, and after suffering nearly 1,000 casualties, mostly from disease or heatstroke, they were evacuated on 30 April. Despite opposition from Penn, Venables attacked Jamaica in late May; primarily a resupply point for Spanish ships, the main settlement of Santiago de la Vega was poorly defended and quickly surrendered, although resistance by Jamaican Maroons

Jamaican Maroons descend from Africans who freed themselves from slavery on the Colony of Jamaica and established communities of free black people in the island's mountainous interior, primarily in the eastern parishes. Africans who were ensl ...

continued in the interior for several years.

By this time the relationship between the two commanders had deteriorated completely, and on 25 June Penn sailed for England hoping to ensure his version of why the expedition failed was heard first. He was followed by Venables, who arrived on 9 September, emaciated and sick; Cromwell accused them both of desertion and threw them both in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

. Although soon released, they were both cashiered

Cashiering (or degradation ceremony), generally within military forces, is a ritual dismissal of an individual from some position of responsibility for a breach of discipline.

Etymology

From the Flemish (to dismiss from service; to discard ...

; Penn returned to the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

after the 1660 Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came t ...

, but this ended Venables' military career.

Later career

Cromwell died in September 1658 and was replaced asProtector

Protector(s) or The Protector(s) may refer to:

Roles and titles

* Protector (title), a title or part of various historical titles of heads of state and others in authority

** Lord Protector, a title that has been used in British constitutional l ...

by his son Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stro ...

, who was dismissed by the army in May 1659. Although sympathetic to restoring the monarchy, Venables avoided participation in Booth's Insurrection of August 1659, which was led by George Booth, a Presbyterian and colleague during the war in Cheshire. When George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

took control of Parliament in February 1660, he appointed Venables governor of Chester but he was removed after The Restoration of Charles II, following pressure from local Royalists, ending his public career.

In 1662, he published a treatise titled ''The Experienced Angler'', with a preface by Izaak Walton, which went through five editions during his lifetime. A prominent supporter of local Nonconformists, he was accused of involvement in the 1663 Farnley Wood Plot

The Farnley Wood Plot was a conspiracy in Yorkshire, England in October 1663. Intended as a major rising to overturn the return to monarchy in 1660, it was undermined by informers, and came to nothing.

The major plotters were Joshua Greathead a ...

, but released without charge. He sheltered the Covenanter dissident William Veitch

William Veitch LL.D. (1794–1885) was a Scottish classical scholar.

Life

He was born in Spittal-on-Rule in Roxburghshire, his family being one of the three main farming families in the area. He attended school in Jedburgh then went to Edinburg ...

after the Pentland Rising in 1666, and in 1683 was indicted as a supporter of the exiled Duke of Monmouth

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

. He also served as a trustee

Trustee (or the holding of a trusteeship) is a legal term which, in its broadest sense, is a synonym for anyone in a position of trust and so can refer to any individual who holds property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility to ...

of Sir John Deane's College, a school established in 1557 with a strong Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

tradition; then in Chester, it moved to Northwich in 1905 and is now a Sixth form college

A sixth form college is an educational institution, where students aged 16 to 19 typically study for advanced school-level qualifications, such as A Levels, Business and Technology Education Council (BTEC) and the International Baccalaureate Di ...

.

In 1668, he purchased an estate at Wincham where he died on 10 December 1687, leaving his property to his daughter Frances.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Venables, Robert 1613 births 1687 deaths Military personnel from Cheshire English generals Roundheads English writers Angling writers British fishers Parliamentarian military personnel of the English Civil War Prisoners in the Tower of London People from Cheshire West and Chester