Robert Louis Stevenson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

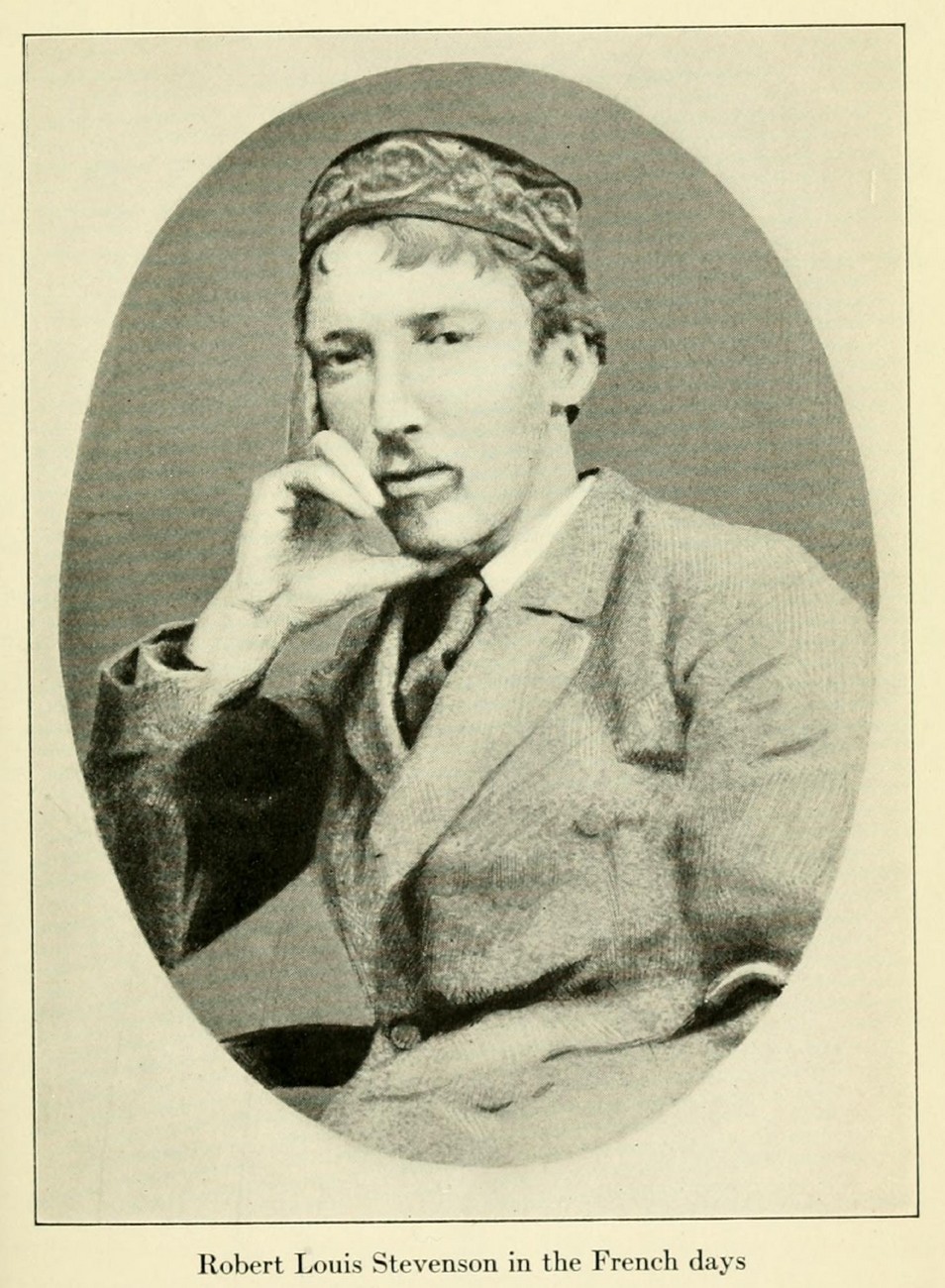

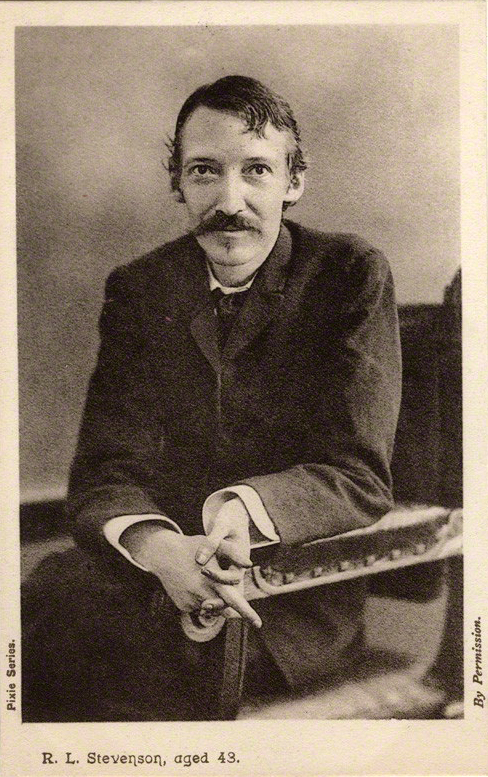

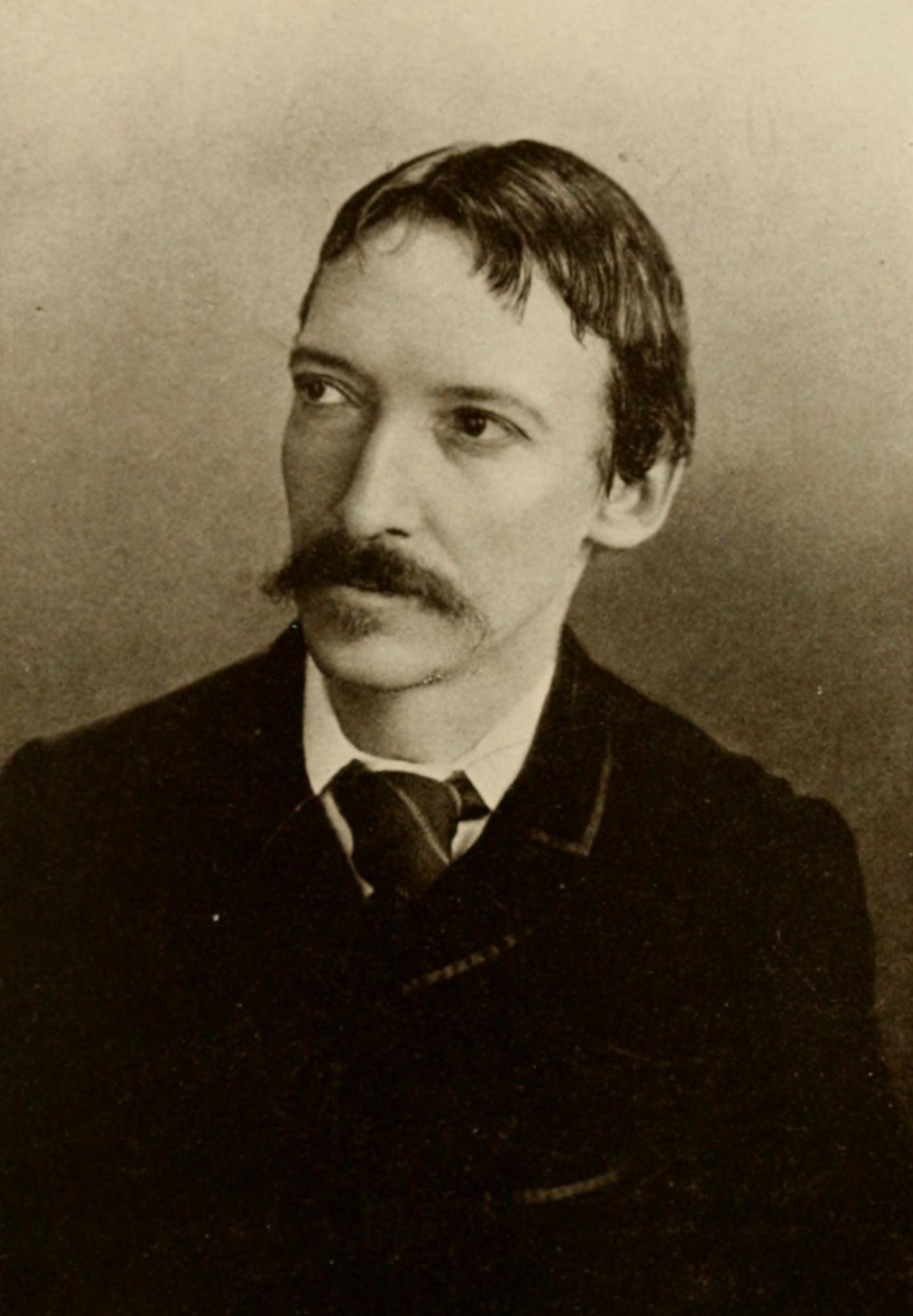

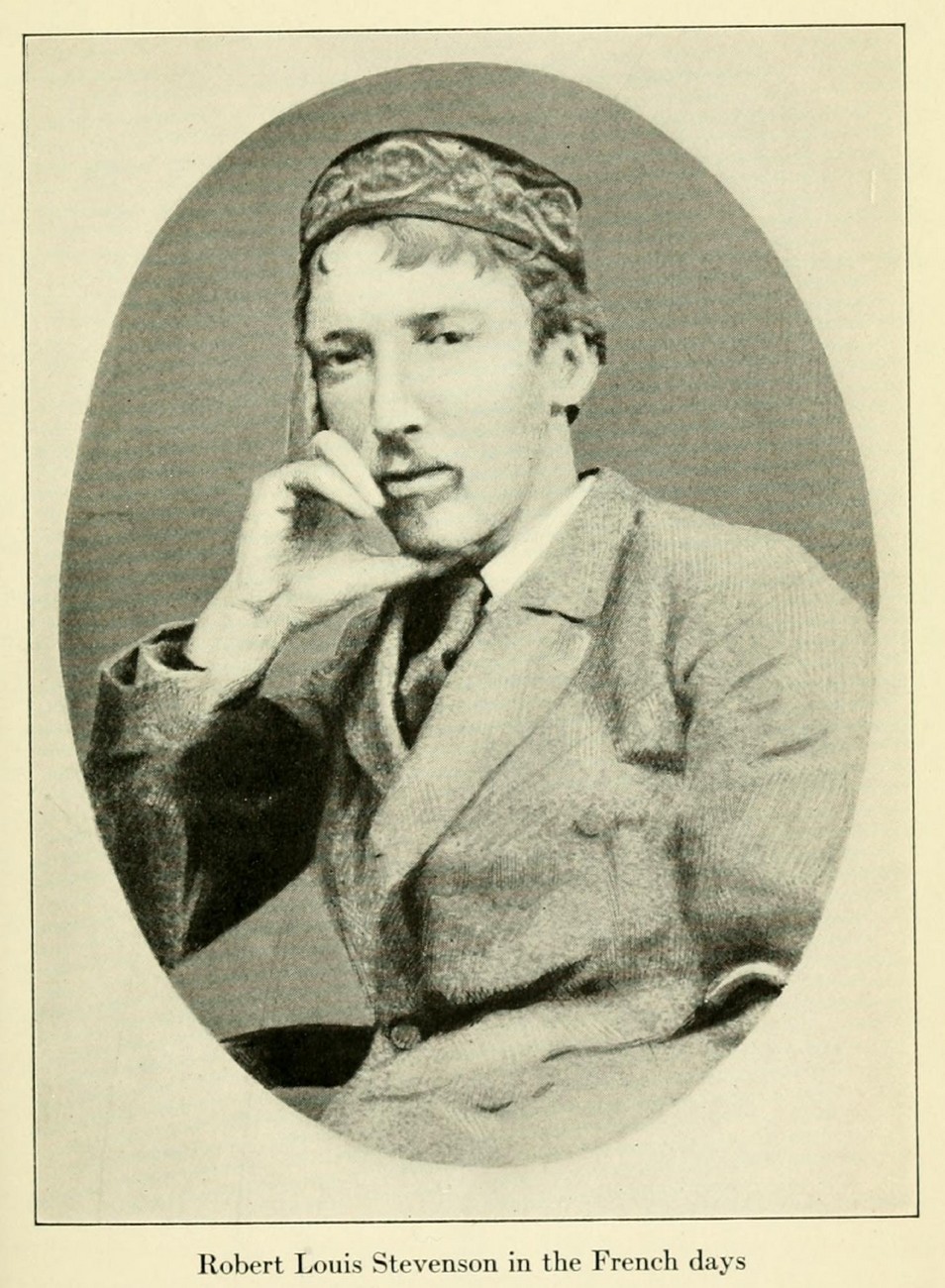

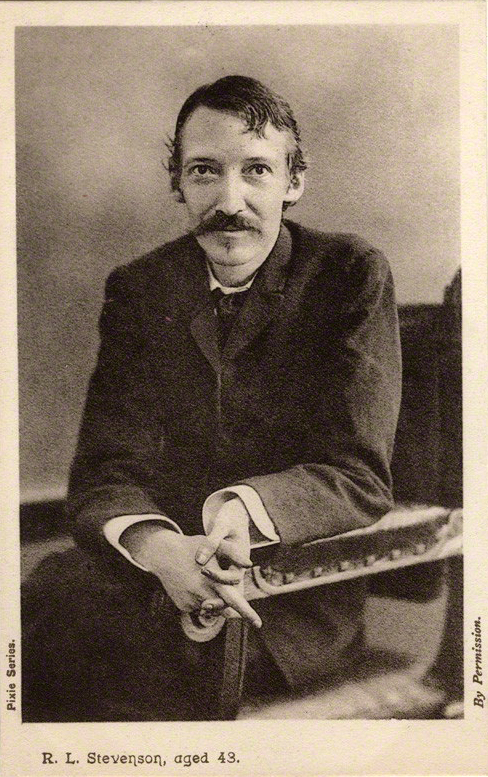

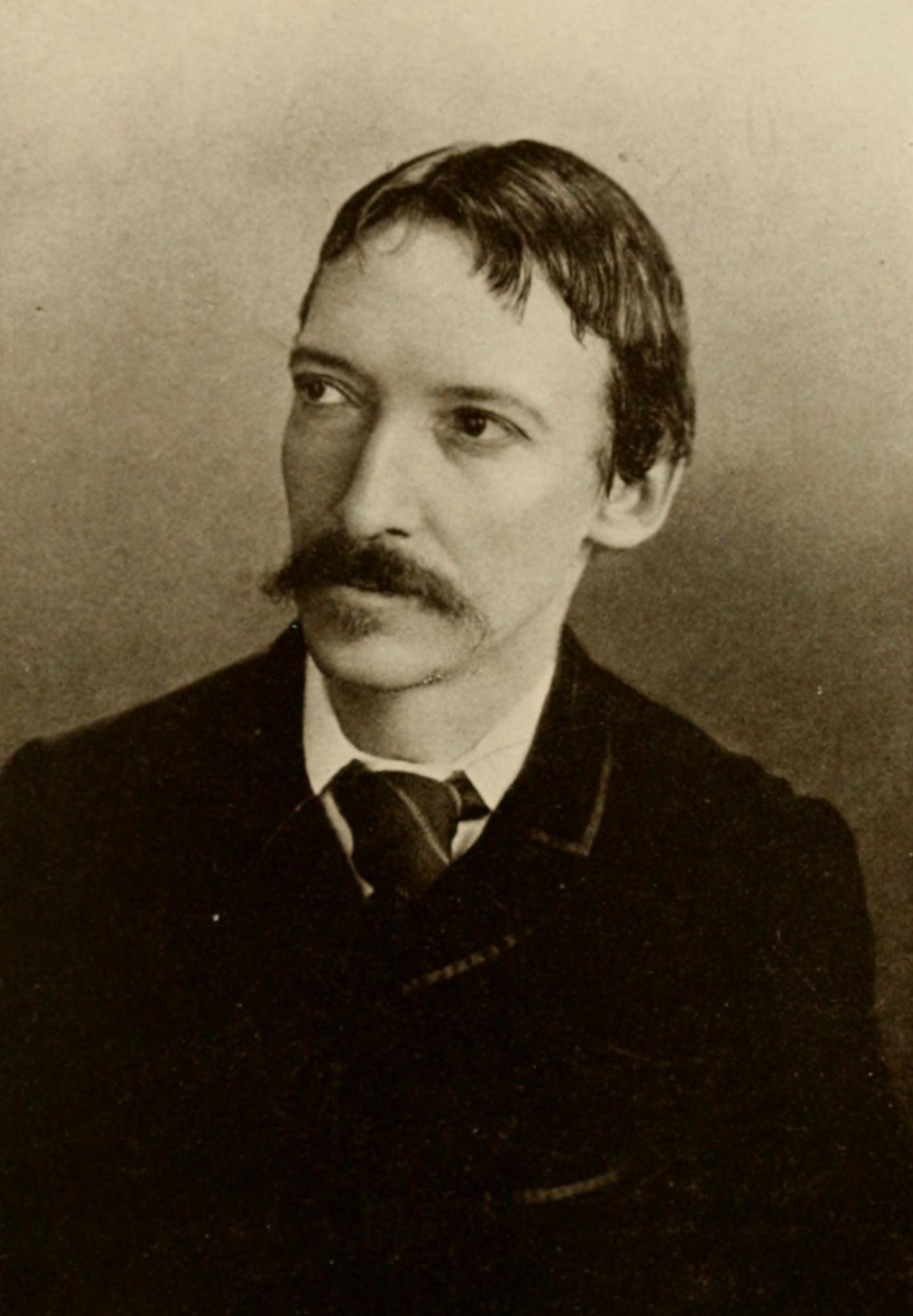

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''

Stevenson was born at 8 Howard Place,

Stevenson was born at 8 Howard Place,  Stevenson's parents were both devout

Stevenson's parents were both devout

In September 1857, when he was six years old, Stevenson went to ''Mr Henderson's School'' in India Street, Edinburgh, but because of poor health stayed only a few weeks and did not return until October 1859, aged eight. During his many absences, he was taught by private tutors. In October 1861, aged ten, he went to

In September 1857, when he was six years old, Stevenson went to ''Mr Henderson's School'' in India Street, Edinburgh, but because of poor health stayed only a few weeks and did not return until October 1859, aged eight. During his many absences, he was taught by private tutors. In October 1861, aged ten, he went to

In late 1873, when he was 23, Stevenson was visiting a cousin in England when he met two people who became very important to him: Fanny (Frances Jane) Sitwell and Sidney Colvin. Sitwell was a 34-year-old woman with a son, who was separated from her husband. She attracted the devotion of many who met her, including Colvin, who married her in 1901. Stevenson was also drawn to her, and they kept up a warm correspondence over several years in which he wavered between the role of a suitor and a son (he addressed her as "

In late 1873, when he was 23, Stevenson was visiting a cousin in England when he met two people who became very important to him: Fanny (Frances Jane) Sitwell and Sidney Colvin. Sitwell was a 34-year-old woman with a son, who was separated from her husband. She attracted the devotion of many who met her, including Colvin, who married her in 1901. Stevenson was also drawn to her, and they kept up a warm correspondence over several years in which he wavered between the role of a suitor and a son (he addressed her as "

The canoe voyage with Simpson brought Stevenson to

The canoe voyage with Simpson brought Stevenson to

Thomas Stevenson died in 1887 leaving his 36-year-old son feeling free to follow the advice of his physician to try a complete change of climate. Stevenson headed for Colorado with his widowed mother and family. But after landing in New York, they decided to spend the winter in the

Thomas Stevenson died in 1887 leaving his 36-year-old son feeling free to follow the advice of his physician to try a complete change of climate. Stevenson headed for Colorado with his widowed mother and family. But after landing in New York, they decided to spend the winter in the

During his college years, Stevenson briefly identified himself as a "red-hot socialist". But already by age 26 he was writing of looking back on this time "with something like regret. ... Now I know that in thus turning Conservative with years, I am going through the normal cycle of change and travelling in the common orbit of men's opinions." His cousin and biographer Sir Graham Balfour claimed that Stevenson "probably throughout life would, if compelled to vote, have always supported the Conservative candidate." In 1866, then 15-year-old Stevenson did vote for

During his college years, Stevenson briefly identified himself as a "red-hot socialist". But already by age 26 he was writing of looking back on this time "with something like regret. ... Now I know that in thus turning Conservative with years, I am going through the normal cycle of change and travelling in the common orbit of men's opinions." His cousin and biographer Sir Graham Balfour claimed that Stevenson "probably throughout life would, if compelled to vote, have always supported the Conservative candidate." In 1866, then 15-year-old Stevenson did vote for

In June 1888, Stevenson chartered the yacht ''Casco'' from Samuel Merritt and set sail with his family from San Francisco. The vessel "plowed her path of snow across the empty deep, far from all track of commerce, far from any hand of help." The sea air and thrill of adventure for a time restored his health, and for nearly three years he wandered the eastern and central Pacific, stopping for extended stays at the Hawaiian Islands, where he became a good friend of King

In June 1888, Stevenson chartered the yacht ''Casco'' from Samuel Merritt and set sail with his family from San Francisco. The vessel "plowed her path of snow across the empty deep, far from all track of commerce, far from any hand of help." The sea air and thrill of adventure for a time restored his health, and for nearly three years he wandered the eastern and central Pacific, stopping for extended stays at the Hawaiian Islands, where he became a good friend of King

Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson,

Stevenson wrote an estimated 700,000 words during his years on Samoa. He completed '' The Beach of Falesá'', the first-person tale of a Scottish

Stevenson wrote an estimated 700,000 words during his years on Samoa. He completed '' The Beach of Falesá'', the first-person tale of a Scottish

The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson

' London: Methuen. 264 (Some sources have stated that he was, instead, attempting to make mayonnaise when he collapsed.) He died within a few hours, at the age of 44, possibly as the result of a brain haemorrhage. According to research published in 2000, Stevenson might have suffered from

Half of Stevenson's original manuscripts are lost, including those of ''

Half of Stevenson's original manuscripts are lost, including those of '' The late 20th century brought a re-evaluation of Stevenson as an artist of great range and insight, a literary theorist, an essayist and social critic, a witness to the colonial

The late 20th century brought a re-evaluation of Stevenson as an artist of great range and insight, a literary theorist, an essayist and social critic, a witness to the colonial

Robert Louis Stevenson statue unveiled by Ian Rankin

BBC News Scotland, Retrieved 27 October 2013 The sculptor of the statue was Alan Herriot, and the money to erect it was raised by the Colinton Community Conservation Trust. Stevenson's house Skerryvore, at the head of Alum Chine, was severely damaged by bombs during a destructive and lethal raid in the Bournemouth Blitz. Despite a campaign to save it, the building was demolished. A garden was designed by the Bournemouth Corporation in 1957 as a memorial to Stevenson, on the site of his Westbourne house, "Skerryvore", which he occupied from 1885 to 1887. A statue of the

Stevenson's former home in Vailima, Samoa, is now a museum dedicated to the later years of his life. The Robert Louis Stevenson Museum presents the house as it was at the time of his death along with two other buildings added to Stevenson's original one, tripling the museum in size. The path to Stevenson's grave at the top of

Stevenson's former home in Vailima, Samoa, is now a museum dedicated to the later years of his life. The Robert Louis Stevenson Museum presents the house as it was at the time of his death along with two other buildings added to Stevenson's original one, tripling the museum in size. The path to Stevenson's grave at the top of

File:Count Girolamo Nerli - Robert Louis Stevenson, 1850 - 1894. Essayist, poet and novelist - Google Art Project.jpg, left, Portrait by Girolamo Nerli, 1892

File:Robert Louis Stevenson and Kalakaua in the King's boathouse (PP-96-14-008).jpg, With Kalakaua in the King's boathouse

File:Robert Louis Stevenson by Sargent.jpg, Portrait by

*'' New Arabian Nights'' (1882) (11 stories)

*'' More New Arabian Nights: The Dynamiter'' (1885) (co-written with Fanny Van de Grift Stevenson)

*'' The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables'' (1887) (6 stories)

*'' Island Nights' Entertainments'' (1893) (3 stories)

*''Fables'' (1896) (20 stories: "The Persons of the Tale", "The Sinking Ship", "The Two Matches", "The Sick Man and the Fireman", "The Devil and the Innkeeper", "The Penitent", "The Yellow Paint", "The House of Eld", "The Four Reformers", "The Man and His Friend", "The Reader", "The Citizen and the Traveller", "The Distinguished Stranger", "The Carthorses and the Saddlehorse", "The Tadpole and the Frog", "Something in It", "Faith, Half Faith and No Faith at All", "The Touchstone", "The Poor Thing" and "The Song of the Morrow")

*'' Tales and Fantasies'' (1905) (3 stories)

*''South Sea Tales'' (1996) (6 stories: "The Beach of Falesá", "The Bottle Imp", "The Isle of Voices", "The Ebb-Tide: A Trio and Quartette", "The Cart-Horses and the Saddle-Horse" and "Something in It")

*'' New Arabian Nights'' (1882) (11 stories)

*'' More New Arabian Nights: The Dynamiter'' (1885) (co-written with Fanny Van de Grift Stevenson)

*'' The Merry Men and Other Tales and Fables'' (1887) (6 stories)

*'' Island Nights' Entertainments'' (1893) (3 stories)

*''Fables'' (1896) (20 stories: "The Persons of the Tale", "The Sinking Ship", "The Two Matches", "The Sick Man and the Fireman", "The Devil and the Innkeeper", "The Penitent", "The Yellow Paint", "The House of Eld", "The Four Reformers", "The Man and His Friend", "The Reader", "The Citizen and the Traveller", "The Distinguished Stranger", "The Carthorses and the Saddlehorse", "The Tadpole and the Frog", "Something in It", "Faith, Half Faith and No Faith at All", "The Touchstone", "The Poor Thing" and "The Song of the Morrow")

*'' Tales and Fantasies'' (1905) (3 stories)

*''South Sea Tales'' (1996) (6 stories: "The Beach of Falesá", "The Bottle Imp", "The Isle of Voices", "The Ebb-Tide: A Trio and Quartette", "The Cart-Horses and the Saddle-Horse" and "Something in It")

* – first published in the 9th edition (1875–1889).

*''Virginibus Puerisque, and Other Papers'' (1881), contains the essays ''Virginibus Puerisque i'' (1876); ''Virginibus Puerisque ii'' (1881); ''Virginibus Puerisque iii: On Falling in Love'' (1877); ''Virginibus Puerisque iv: The Truth of Intercourse'' (1879); ''Crabbed Age and Youth'' (1878); ''An Apology for Idlers'' (1877); ''Ordered South'' (1874); ''Aes Triplex'' (1878); ''El Dorado'' (1878); ''The English Admirals'' (1878); ''Some Portraits by Raeburn'' (previously unpublished); ''Child's Play'' (1878); ''Walking Tours'' (1876); ''Pan's Pipes'' (1878); ''A Plea for Gas Lamps'' (1878).

*''Familiar Studies of Men and Books'' (1882) containing ''Preface, by Way of Criticism'' (not previously published); ''Victor Hugo's Romances'' (1874); ''Some Aspects of Robert Burns'' (1879); ''The Gospel According to Walt Whitman'' (1878); ''Henry David Thoreau: His Character and Opinions'' (1880); ''Yoshida-Torajiro'' (1880); ''François Villon, Student, Poet, Housebreaker'' (1877); ''Charles of Orleans'' (1876); ''Samuel Pepys'' (1881); ''John Knox and his Relations to Women'' (1875).

*'' Memories and Portraits'' (1887), a collection of essays.

*''On the Choice of a Profession'' (1887)

*''The Day After Tomorrow'' (1887)

*''Memoir of

* – first published in the 9th edition (1875–1889).

*''Virginibus Puerisque, and Other Papers'' (1881), contains the essays ''Virginibus Puerisque i'' (1876); ''Virginibus Puerisque ii'' (1881); ''Virginibus Puerisque iii: On Falling in Love'' (1877); ''Virginibus Puerisque iv: The Truth of Intercourse'' (1879); ''Crabbed Age and Youth'' (1878); ''An Apology for Idlers'' (1877); ''Ordered South'' (1874); ''Aes Triplex'' (1878); ''El Dorado'' (1878); ''The English Admirals'' (1878); ''Some Portraits by Raeburn'' (previously unpublished); ''Child's Play'' (1878); ''Walking Tours'' (1876); ''Pan's Pipes'' (1878); ''A Plea for Gas Lamps'' (1878).

*''Familiar Studies of Men and Books'' (1882) containing ''Preface, by Way of Criticism'' (not previously published); ''Victor Hugo's Romances'' (1874); ''Some Aspects of Robert Burns'' (1879); ''The Gospel According to Walt Whitman'' (1878); ''Henry David Thoreau: His Character and Opinions'' (1880); ''Yoshida-Torajiro'' (1880); ''François Villon, Student, Poet, Housebreaker'' (1877); ''Charles of Orleans'' (1876); ''Samuel Pepys'' (1881); ''John Knox and his Relations to Women'' (1875).

*'' Memories and Portraits'' (1887), a collection of essays.

*''On the Choice of a Profession'' (1887)

*''The Day After Tomorrow'' (1887)

*''Memoir of

*''

*''

Early works

including books, collected and uncollected essays and serialisations from

Robert Louis Stevenson

at the British Library *Archival material a

Leeds University Library

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

Robert Louis Stevenson collection, circa 1890-1923

* Edwin J. Beinecke Collection of Robert Louis Stevenson. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. * Robert Louis Stevenson Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. {{DEFAULTSORT:Stevenson, Robert Louis 1850 births 1894 deaths 19th-century pseudonymous writers 19th-century Scottish male writers 19th-century Scottish novelists 19th-century Scottish poets 19th-century Scottish short story writers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh British children's poets British emigrants to Samoa British ghost story writers British non-fiction outdoors writers British weird fiction writers Clan Balfour Scottish fabulists Former atheists and agnostics Former Presbyterians Lallans poets Maritime writers Mythopoeic writers People educated at Edinburgh Academy Samoan people of Scottish descent Samoan writers Scottish children's writers Scottish expatriates in the United States Scottish historical novelists Scottish horror writers Scottish male songwriters Scottish short story writers Scottish travel writers Stevenson family (Scotland) Victorian novelists Victorian short story writers Writers from Edinburgh Writers of Gothic fiction 19th-century Scottish dramatists and playwrights Scottish male dramatists and playwrights Writers of historical fiction set in the early modern period 19th-century Scottish biographers 19th-century Scottish essayists Scottish male essayists Scottish literary critics 19th-century Scottish non-fiction writers Scottish male non-fiction writers Deaths in Samoa

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island

''Treasure Island'' (originally titled ''The Sea Cook: A Story for Boys''Hammond, J. R. 1984. "Treasure Island." In ''A Robert Louis Stevenson Companion'', Palgrave Macmillan Literary Companions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. .) is an adventure a ...

'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' is an 1886 Gothic horror novella by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. It follows Gabriel John Utterson, a London-based legal practitioner who investigates a series of strange occurrences between ...

'', '' Kidnapped'' and '' A Child's Garden of Verses''.

Born and educated in Edinburgh, Stevenson suffered from serious bronchial trouble for much of his life but continued to write prolifically and travel widely in defiance of his poor health. As a young man, he mixed in London literary circles, receiving encouragement from Sidney Colvin, Andrew Lang

Andrew Lang (31 March 1844 – 20 July 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a folkloristics, collector of folklore, folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang lectur ...

, Edmund Gosse

Sir Edmund William Gosse (; 21 September 184916 May 1928) was an English poet, author and critic. He was strictly brought up in a small Protestant sect, the Plymouth Brethren, but broke away sharply from that faith. His account of his childhood ...

, Leslie Stephen

Sir Leslie Stephen (28 November 1832 – 22 February 1904) was an English author, critic, historian, biographer, mountaineer, and an Ethical Culture, Ethical movement activist. He was also the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell and the ...

and W. E. Henley, the last of whom may have provided the model for Long John Silver

Long John Silver is a fictional character and the main antagonist in the 1883 novel '' Treasure Island'' by Robert Louis Stevenson. The most colourful and complex character in the book, he continues to appear in popular culture. His missing leg ...

in ''Treasure Island''. In 1890, he settled in Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabited ...

where, alarmed at increasing European and American influence in the South Sea islands, his writing turned from romance and adventure fiction toward a darker realism. He died of a stroke in his island home in 1894 at age 44.

A celebrity in his lifetime, Stevenson's critical reputation has fluctuated since his death, though today his works are held in general acclaim. In 2018, he was ranked just behind Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

as the 26th-most-translated author in the world.

Family and education

Childhood and youth

Stevenson was born at 8 Howard Place,

Stevenson was born at 8 Howard Place, Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, Scotland, on 13 November 1850 to Thomas Stevenson (1818–1887), a leading lighthouse engineer, and his wife, Margaret Isabella (born Balfour, 1829–1897). He was christened Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson. At about age 18, he changed the spelling of "Lewis" to "Louis", and he dropped "Balfour" in 1873.

Lighthouse design was the family's profession; Thomas's father (Robert's grandfather) was the civil engineer Robert Stevenson, and Thomas's brothers (Robert's uncles) Alan

Alan may refer to:

People

*Alan (surname), an English and Kurdish surname

* Alan (given name), an English given name

** List of people with given name Alan

''Following are people commonly referred to solely by "Alan" or by a homonymous name.''

* ...

and David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Dam ...

were in the same field.Paxton (2004). Thomas's maternal grandfather Thomas Smith had been in the same profession. However, Robert's mother's family were gentry

Gentry (from Old French , from ) are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past. ''Gentry'', in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to Landed property, landed es ...

, tracing their lineage back to Alexander Balfour, who had held the lands of Inchrye in Fife in the fifteenth century. His mother's father, Lewis Balfour (1777–1860), was a minister of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

at nearby Colinton

Colinton is a suburb of Edinburgh, Scotland situated southwest of the city centre. Up until the late 18th century it appears on maps as Collington. It is bordered by Dreghorn to the south and Craiglockhart to the north-east. To the north-w ...

, and her siblings included physician George William Balfour and marine engineer James Balfour. Stevenson spent the greater part of his boyhood holidays in his maternal grandfather's house. "Now I often wonder what I inherited from this old minister," Stevenson wrote. "I must suppose, indeed, that he was fond of preaching sermons, and so am I, though I never heard it maintained that either of us loved to hear them."

Lewis Balfour and his daughter both had weak chests, so they often needed to stay in warmer climates for their health. Stevenson inherited a tendency to coughs and fevers, exacerbated when the family moved to a damp, chilly house at 1 Inverleith Terrace in 1851. The family moved again to the sunnier 17 Heriot Row when Stevenson was six years old, but the tendency to extreme sickness in winter remained with him until he was 11. Illness was a recurrent feature of his adult life and left him extraordinarily thin. Contemporaneous views were that he had tuberculosis, but more recent views are that it was bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is a disease in which there is permanent enlargement of parts of the bronchi, airways of the lung. Symptoms typically include a chronic cough with sputum, mucus production. Other symptoms include shortness of breath, hemoptysis, co ...

or sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis (; also known as Besnier–Boeck–Schaumann disease) is a disease involving abnormal collections of White blood cell, inflammatory cells that form lumps known as granulomata. The disease usually begins in the lungs, skin, or lymph n ...

. The family also summered in the spa town

A spa town is a resort town based on a mineral spa (a developed mineral spring). Patrons visit spas to "take the waters" for their purported health benefits.

Thomas Guidott set up a medical practice in the English town of Bath, Somerset, Ba ...

of Bridge of Allan

Bridge of Allan (, ), also known colloquially as ''Bofa'', is a former spa town in the Stirling (council area), Stirling council area in Scotland, just north of the city of Stirling.

Overlooked by the National Wallace Monument, it lies on th ...

, in North Berwick

North Berwick (; ) is a seaside resort, seaside town and former royal burgh in East Lothian, Scotland. It is situated on the south shore of the Firth of Forth, approximately east-northeast of Edinburgh. North Berwick became a fashionable holi ...

, and in Peebles

Peebles () is a town in the Scottish Borders, Scotland. It was historically a royal burgh and the county town of Peeblesshire. According to the United Kingdom census, 2011, 2011 census, the population was 8,376 and the estimated population in ...

for the sake of Stevenson's and his mother's health; "Stevenson's cave" in Bridge of Allan was reportedly the inspiration for the character Ben Gunn's cave dwelling in Stevenson's 1883 novel ''Treasure Island

''Treasure Island'' (originally titled ''The Sea Cook: A Story for Boys''Hammond, J. R. 1984. "Treasure Island." In ''A Robert Louis Stevenson Companion'', Palgrave Macmillan Literary Companions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. .) is an adventure a ...

''.

Stevenson's parents were both devout

Stevenson's parents were both devout Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

, but the household was not strict in its adherence to Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

principles. His nurse Alison Cunningham (known as Cummy) was more fervently religious. Her mix of Calvinism and folk beliefs were an early source of nightmares for the child, and he showed a precocious concern for religion. But she also cared for him tenderly in illness, reading to him from John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; 1628 – 31 August 1688) was an English writer and preacher. He is best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress'', which also became an influential literary model. In addition to ''The Pilgrim' ...

and the Bible as he lay sick in bed and telling tales of the Covenanters

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son ...

. Stevenson recalled this time of sickness in "The Land of Counterpane" in '' A Child's Garden of Verses'' (1885), dedicating the book to his nurse.

Stevenson was an only child, both strange-looking and eccentric, and he found it hard to fit in when he was sent to a nearby school at age 6, a problem repeated at age 11 when he went on to the Edinburgh Academy

The Edinburgh Academy is a Private schools in the United Kingdom, private day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, which was opened in 1824. The original building, on Henderson Row in Stockbridge, Edinburgh, Stockbridge, is now part of the Senior Scho ...

; but he mixed well in lively games with his cousins in summer holidays at Colinton

Colinton is a suburb of Edinburgh, Scotland situated southwest of the city centre. Up until the late 18th century it appears on maps as Collington. It is bordered by Dreghorn to the south and Craiglockhart to the north-east. To the north-w ...

. His frequent illnesses often kept him away from his first school, so he was taught for long stretches by private tutors. He was a late reader, learning at age 7 or 8, but even before this he dictated stories to his mother and nurse,Mehew (2004). and he compulsively wrote stories throughout his childhood. His father was proud of this interest; he had also written stories in his spare time until his own father had found them and had told him to "give up such nonsense and mind your business." He paid for the printing of Robert's first publication at 16, entitled ''The Pentland Rising: A Page of History, 1666''. It was an account of the Covenanters' rebellion and was published in 1866, the 200th anniversary of the event.

Education

In September 1857, when he was six years old, Stevenson went to ''Mr Henderson's School'' in India Street, Edinburgh, but because of poor health stayed only a few weeks and did not return until October 1859, aged eight. During his many absences, he was taught by private tutors. In October 1861, aged ten, he went to

In September 1857, when he was six years old, Stevenson went to ''Mr Henderson's School'' in India Street, Edinburgh, but because of poor health stayed only a few weeks and did not return until October 1859, aged eight. During his many absences, he was taught by private tutors. In October 1861, aged ten, he went to Edinburgh Academy

The Edinburgh Academy is a Private schools in the United Kingdom, private day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, which was opened in 1824. The original building, on Henderson Row in Stockbridge, Edinburgh, Stockbridge, is now part of the Senior Scho ...

, an independent school for boys, and stayed there sporadically for about fifteen months. In the autumn of 1863, he spent one term at an English boarding school at Spring Grove in Isleworth

Isleworth ( ) is a suburban town in the London Borough of Hounslow, West London, England.

It lies immediately east of Hounslow and west of the River Thames and its tributary the River Crane, London, River Crane. Isleworth's original area of ...

in Middlesex (now an urban area of West London). In October 1864, following an improvement to his health, the 13-year-old was sent to Robert Thomson's private school in Frederick Street, Edinburgh, where he remained until he went to university. In November 1867, Stevenson entered the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

to study engineering. From the start he showed no enthusiasm for his studies and devoted much energy to avoiding lectures. This time was more important for the friendships he made with other students in The Speculative Society (an exclusive debating club), particularly with Charles Baxter, who would become Stevenson's financial agent, and with a professor, Fleeming Jenkin

Henry Charles Fleeming Jenkin Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (; 25 March 1833 – 12 June 1885) was a British engineer, inventor, economist, linguist, actor and dramatist known as the inventor of the cable car or Aerial tramway#Telpherage, t ...

, whose house staged amateur drama in which Stevenson took part, and whose biography he would later write. Perhaps most important at this point in his life was a cousin, Robert Alan Mowbray Stevenson (known as "Bob"), a lively and light-hearted young man who, instead of the family profession, had chosen to study art.

Holidays in Swanston

In 1867, Stevenson's family took a lease on Swanston Cottage, in the village of Swanston at the foot of the Pentland Hills, for use as a summer holiday home. They held the lease until 1880. During their tenancy, the young Robert Louis made frequent use of the cottage, being attracted by the quiet country life and the feeling of remoteness. It is likely that the time he spent there influenced his later writing as well as his wider outlook on life, particularly his love of nature and of wild places. The house and its romantic location are thought to have inspired several of his works.Lighthouse inspections

Each year during his university holidays, Stevenson also travelled to inspect the family's engineering works. In 1868, this took him toAnstruther

Anstruther ( ; ) is a coastal town in Fife, Scotland, situated on the north-shore of the Firth of Forth and south-southeast of St Andrews. The town comprises two settlements, Anstruther Easter and Anstruther Wester, which are divided by a st ...

and for a stay of six weeks in Wick

Wick most often refers to:

* Capillary action ("wicking")

** Candle wick, the cord used in a candle or oil lamp

** Solder wick, a copper-braided wire used to desolder electronic contacts

Wick or WICK may also refer to:

Places and placenames ...

, where his family was building a sea wall and had previously built a lighthouse. He was to return to Wick several times over his lifetime and included it in his travel writings. He also accompanied his father on his official tour of Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

and Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

islands lighthouses in 1869 and spent three weeks on the island of Erraid in 1870. He enjoyed the travels more for the material they gave for his writing than for any engineering interest. The voyage with his father pleased him because a similar journey of Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

with Robert Stevenson had provided the inspiration for Scott's 1822 novel '' The Pirate''. In April 1871, Stevenson notified his father of his decision to pursue a life of letters. Though the elder Stevenson was naturally disappointed, the surprise cannot have been great, and Stevenson's mother reported that he was "wonderfully resigned" to his son's choice. To provide some security, it was agreed that Stevenson should read law (again at Edinburgh University) and be called to the Scottish bar. In his 1887 poetry collection ''Underwoods'', Stevenson muses on his having turned from the family profession:

Say not of me that weakly I declined

The labours of my sires, and fled the sea,

The towers we founded and the lamps we lit,

To play at home with paper like a child.

But rather say: ''In the afternoon of time''

''A strenuous family dusted from its hands''

''The sand of granite, and beholding far''

''Along the sounding coast its pyramids''

''And tall memorials catch the dying sun,''

''Smiled well content, and to this childish task''

''Around the fire addressed its evening hours.''

Rejection of church dogma

In other respects too, Stevenson was moving away from his upbringing. His dress became moreBohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, originally practised by 19th–20th century European and American artists and writers.

* Bohemian style, a ...

; he already wore his hair long, but he now took to wearing a velveteen jacket and rarely attended parties in conventional evening dress. Within the limits of a strict allowance, he visited cheap pubs and brothels. More significantly, he had come to reject Christianity and declared himself an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

. In January 1873, when he was 22, his father came across the constitution of the LJR (Liberty, Justice, Reverence) Club, of which Stevenson and his cousin Bob were members, which began: "Disregard everything our parents have taught us". Questioning his son about his beliefs, he discovered the truth. Stevenson no longer believed in God and had grown tired of pretending to be something he was not: "am I to live my whole life as one falsehood?" His father professed himself devastated: "You have rendered my whole life a failure." His mother accounted the revelation "the heaviest affliction" to befall her. "O Lord, what a pleasant thing it is", Stevenson wrote to his friend Charles Baxter, "to have just damned the happiness of (probably) the only two people who care a damn about you in the world."

Stevenson's rejection of the Presbyterian Church and Christian dogma, however, did not turn into lifelong atheism or agnosticism. On 15 February 1878, the 27-year-old wrote to his father and stated:

Stevenson did not resume attending church in Scotland. However, he did teach Sunday School lessons in Samoa, and prayers he wrote in his final years were published posthumously.

"An Apology for Idlers"

Justifying his rejection of an established profession, in 1877 Stevenson offered "An Apology for Idlers". "A happy man or woman", he reasoned, "is a better thing to find than a five-pound note. He or she is a radiating focus of goodwill" and a practical demonstration of "the great Theorem of the Liveableness of Life". So that if they cannot be happy in the "handicap race for sixpenny pieces", let them take their own "by-road".Early writing and travels

Literary and artistic connections

In late 1873, when he was 23, Stevenson was visiting a cousin in England when he met two people who became very important to him: Fanny (Frances Jane) Sitwell and Sidney Colvin. Sitwell was a 34-year-old woman with a son, who was separated from her husband. She attracted the devotion of many who met her, including Colvin, who married her in 1901. Stevenson was also drawn to her, and they kept up a warm correspondence over several years in which he wavered between the role of a suitor and a son (he addressed her as "

In late 1873, when he was 23, Stevenson was visiting a cousin in England when he met two people who became very important to him: Fanny (Frances Jane) Sitwell and Sidney Colvin. Sitwell was a 34-year-old woman with a son, who was separated from her husband. She attracted the devotion of many who met her, including Colvin, who married her in 1901. Stevenson was also drawn to her, and they kept up a warm correspondence over several years in which he wavered between the role of a suitor and a son (he addressed her as "Madonna

Madonna Louise Ciccone ( ; born August 16, 1958) is an American singer, songwriter, record producer, and actress. Referred to as the "Queen of Pop", she has been recognized for her continual reinvention and versatility in music production, ...

"). Colvin became Stevenson's literary adviser and was the first editor of his letters after his death. He placed Stevenson's first paid contribution in ''The Portfolio

''The Portfolio'' was a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British monthly art magazine published in London from 1870 to 1893. It was founded by Philip Gilbert Hamerton and promoted contemporary printmaking, especially etching, and ...

'', an essay titled "Roads".

Stevenson was soon active in London literary life, becoming acquainted with many of the writers of the time, including Andrew Lang

Andrew Lang (31 March 1844 – 20 July 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a folkloristics, collector of folklore, folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang lectur ...

, Edmund Gosse

Sir Edmund William Gosse (; 21 September 184916 May 1928) was an English poet, author and critic. He was strictly brought up in a small Protestant sect, the Plymouth Brethren, but broke away sharply from that faith. His account of his childhood ...

and Leslie Stephen

Sir Leslie Stephen (28 November 1832 – 22 February 1904) was an English author, critic, historian, biographer, mountaineer, and an Ethical Culture, Ethical movement activist. He was also the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell and the ...

, the editor of ''The Cornhill Magazine

''The Cornhill Magazine'' (1860–1975) was a monthly Victorian magazine and literary journal named after the street address of the founding publisher Smith, Elder & Co. at 65 Cornhill in London.Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor, ''Dictionar ...

'', who took an interest in Stevenson's work. Stephen took Stevenson to visit a patient at the Edinburgh Infirmary named William Ernest Henley

William Ernest Henley (23 August 1849 11 July 1903) was a British poet, writer, critic and editor. Though he wrote several books of poetry, Henley is remembered most often for his 1875 poem "Invictus". A fixture in London literary circles, th ...

, an energetic and talkative poet with a wooden leg. Henley became a close friend and occasional literary collaborator, until a quarrel broke up the friendship in 1888, and he is often considered to be the inspiration for Long John Silver

Long John Silver is a fictional character and the main antagonist in the 1883 novel '' Treasure Island'' by Robert Louis Stevenson. The most colourful and complex character in the book, he continues to appear in popular culture. His missing leg ...

in ''Treasure Island''.

Stevenson was sent to Menton

Menton (; in classical norm or in Mistralian norm, , ; ; or depending on the orthography) is a Commune in France, commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italia ...

on the French Riviera

The French Riviera, known in French as the (; , ; ), is the Mediterranean coastline of the southeast corner of France. There is no official boundary, but it is considered to be the coastal area of the Alpes-Maritimes department, extending fr ...

in November 1873 to recuperate after his health failed. He returned in better health in April 1874 and settled down to his studies, but he returned to France several times after that. He made long and frequent trips to the neighbourhood of the Forest of Fontainebleau

The forest of Fontainebleau (, or , meaning, in old French, "forest of Ericaceae, heather") is a mixed deciduous forest lying southeast of Paris, France. It is located primarily in the arrondissement of Fontainebleau in the southwestern part of th ...

, staying at Barbizon

Barbizon () is a commune (town) in the Seine-et-Marne department in north-central France. It is located near the Fontainebleau Forest.

Demographics

The inhabitants are called ''Barbizonais''.

Art history

The Barbizon school of painters is n ...

, Grez-sur-Loing

Grez-sur-Loing (, literally ''Grez on Loing''; formerly Grès-en-Gâtinais, literally ''Grès in Gâtinais'') is a Communes of France, commune in the Seine-et-Marne Departments of France, department in north-central France. It is 6 km north o ...

and Nemours

Nemours () is a Communes of France, commune in the Seine-et-Marne Departments of France, department in the Île-de-France Regions of France, region in north-central France.

Geography

Nemours is located on the Loing and its canal, c. south of M ...

and becoming a member of the artists' colonies there. He also travelled to Paris to visit galleries and the theatres. He qualified for the Scottish bar in July 1875, aged 24, and his father added a brass plate to the Heriot Row house reading "R.L. Stevenson, Advocate". His law studies did influence his books, but he never practised law; all his energies were spent in travel and writing. One of his journeys was a canoe voyage in Belgium and France with Sir Walter Simpson, a friend from the Speculative Society, a frequent travel companion, and the author of ''The Art of Golf'' (1887). This trip was the basis of his first travel book ''An Inland Voyage

''An Inland Voyage'' (1878) is a travelogue by Robert Louis Stevenson about a canoeing trip through France and Belgium in 1876. It is Stevenson's earliest book and a pioneering work of outdoor literature.

As a young man, Stevenson desired ...

'' (1878).

Stevenson had a long correspondence with fellow Scot J.M. Barrie. He invited Barrie to visit him in Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabited ...

, but the two never met.

Marriage

The canoe voyage with Simpson brought Stevenson to

The canoe voyage with Simpson brought Stevenson to Grez-sur-Loing

Grez-sur-Loing (, literally ''Grez on Loing''; formerly Grès-en-Gâtinais, literally ''Grès in Gâtinais'') is a Communes of France, commune in the Seine-et-Marne Departments of France, department in north-central France. It is 6 km north o ...

in September 1876, where he met Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne (1840–1914), born in Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

. She had married at age 17 and moved to Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

to rejoin husband Samuel after his participation in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. Their children were Isobel (or "Belle"), Lloyd and Hervey (who died in 1875). But anger over her husband's infidelities led to a number of separations. In 1875, she had taken her children to France where she and Isobel studied art. By the time Stevenson met her, Fanny was herself a magazine short-story writer of recognised ability.

Stevenson returned to Britain shortly after this first meeting, but Fanny apparently remained in his thoughts, and he wrote the essay "On falling in love" for ''The Cornhill Magazine''. They met again early in 1877 and became lovers. Stevenson spent much of the following year with her and her children in France. In August 1878, she returned to San Francisco and Stevenson remained in Europe, making the walking trip that formed the basis for ''Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes

''Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes'' (1879) is one of Robert Louis Stevenson's earliest published works and is considered a pioneering classic of outdoor literature.

Background

Stevenson was in his late 20s and still dependent on his par ...

'' (1879). But he set off to join her in August 1879, aged 28, against the advice of his friends and without notifying his parents. He took a second-class passage on the steamship '' Devonia'', in part to save money but also to learn how others travelled and to increase the adventure of the journey. He then travelled overland by train from New York City to California. He later wrote about the experience in '' The Amateur Emigrant''. It was a good experience for his writing, but it broke his health.

He was near death when he arrived in Monterey, California

Monterey ( ; ) is a city situated on the southern edge of Monterey Bay, on the Central Coast (California), Central Coast of California. Located in Monterey County, California, Monterey County, the city occupies a land area of and recorded a popu ...

, where some local ranchers nursed him back to health. He stayed for a time at the French Hotel located at 530 Houston Street, now a museum dedicated to his memory called the " Stevenson House". While there, he often dined "on the cuff," as he said, at a nearby restaurant run by Frenchman Jules Simoneau, which stood at what is now Simoneau Plaza; several years later, he sent Simoneau an inscribed copy of his novel ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' is an 1886 Gothic horror novella by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. It follows Gabriel John Utterson, a London-based legal practitioner who investigates a series of strange occurrences between ...

'' (1886), writing that it would be a stranger case still if Robert Louis Stevenson ever forgot Jules Simoneau. While in Monterey, he wrote an evocative article about "the Old Pacific Capital" of Monterey.

By December 1879, aged 29, Stevenson had recovered his health enough to continue to San Francisco where he struggled "all alone on forty-five cents a day, and sometimes less, with quantities of hard work and many heavy thoughts," in an effort to support himself through his writing. But by the end of the winter, his health was broken again and he found himself at death's door. Fanny was now divorced and recovered from her own illness, and she came to his bedside and nursed him to recovery. "After a while," he wrote, "my spirit got up again in a divine frenzy, and has since kicked and spurred my vile body forward with great emphasis and success." When his father heard of his 28-year-old son's condition, he cabled him money to help him through this period.

Fanny and Robert were married in May 1880. She was 40; he was 29. He said that he was "a mere complication of cough and bones, much fitter for an emblem of mortality than a bridegroom." He travelled with his new wife and her son Lloyd north of San Francisco to Napa Valley

Napa Valley is an American Viticultural Area (AVA) in Napa County, California. The area was established by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) on February 27, 1981, after a 1978 petition submitted by the Napa Valley Vin ...

and spent a summer honeymoon at an abandoned mining camp on Mount Saint Helena

Mount Saint Helena (Wappo: Kanamota, "Human Mountain") is a peak in the Mayacamas Mountains with flanks in Napa, Sonoma, and Lake counties of California. Composed of uplifted volcanic rocks from the Clear Lake Volcanic Field, it is one of the ...

(today designated Robert Louis Stevenson State Park). He wrote about this experience in '' The Silverado Squatters''. He met Charles Warren Stoddard, co-editor of the ''Overland Monthly

The ''Overland Monthly'' was a monthly literary magazine, literary and cultural magazine, based in California, United States. It was founded in 1868 and published between the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th centu ...

'' and author of ''South Sea Idylls'', who urged Stevenson to travel to the South Pacific, an idea which returned to him many years later. In August 1880, he sailed with Fanny and Lloyd from New York to Britain and found his parents and his friend Sidney Colvin on the wharf at Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, happy to see him return home. Gradually, his wife was able to patch up differences between father and son and make herself a part of the family through her charm and wit.

England, and back to the United States

The Stevensons shuttled back and forth between Scotland and the Continent (twice wintering inDavos

Davos (, ; or ; ; Old ) is an Alpine resort town and municipality in the Prättigau/Davos Region in the canton of Graubünden, Switzerland. It has a permanent population of (). Davos is located on the river Landwasser, in the Rhaetian ...

) before finally, in 1884, settling in Westbourne in the English south-coast town of Bournemouth

Bournemouth ( ) is a coastal resort town in the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole unitary authority area, in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. At the 2021 census, the built-up area had a population of 196,455, making it the largest ...

. Stevenson had moved there to benefit from its sea air. They lived in a house Stevenson named 'Skerryvore' after a Scottish lighthouse built by his uncle Alan.

From April 1885, 34-year-old Stevenson had the company of the novelist Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

. They had met previously in London and had recently exchanged views in journal articles on the "art of fiction" and thereafter in a correspondence in which they expressed their admiration for each other's work. After James had moved to Bournemouth to help support his invalid sister, Alice

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

, he took up the invitation to pay daily visits to Skerryvore for conversation at the Stevensons' dinner table.

Largely bedridden, Stevenson described himself as living "like a weevil in a biscuit." Yet, despite ill health, during his three years in Westbourne, Stevenson wrote the bulk of his most popular work: ''Treasure Island

''Treasure Island'' (originally titled ''The Sea Cook: A Story for Boys''Hammond, J. R. 1984. "Treasure Island." In ''A Robert Louis Stevenson Companion'', Palgrave Macmillan Literary Companions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. .) is an adventure a ...

'', '' Kidnapped'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' is an 1886 Gothic horror novella by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. It follows Gabriel John Utterson, a London-based legal practitioner who investigates a series of strange occurrences between ...

'' (which established his wider reputation), '' A Child's Garden of Verses'' and '' Underwoods''.

Adirondacks

The Adirondack Mountains ( ) are a massif of mountains in Northeastern New York (state), New York which form a circular dome approximately wide and covering about . The region contains more than 100 peaks, including Mount Marcy, which is the hi ...

at a cure cottage now known as Stevenson Cottage at Saranac Lake, New York

Saranac Lake is a village in the state of New York, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 4,887, making it the largest community by population in the Adirondack Park.U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Report, Saranac Lake village, New ...

. During the intensely cold winter, Stevenson wrote some of his best essays, including ''Pulvis et Umbra''. He also began ''The Master of Ballantrae

''The Master of Ballantrae: A Winter's Tale'' is an 1889 novel by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson, focusing upon the conflict between two brothers, Scottish noblemen whose family is torn apart by the Jacobite rising of 1745. He wo ...

'' and lightheartedly planned a cruise to the southern Pacific Ocean for the following summer.

Reflections on the art of writing

Stevenson's critical essays on literature contain "few sustained analyses of style or content". In "A Penny Plain and Two-pence Coloured" (1884) he suggests that his own approach owed much to the exaggerated and romantic world that, as a child, he had entered as proud owner of Skelt's Juvenile Drama—a toy set of cardboard characters who were actors in melodramatic dramas. "A Gossip on Romance" (1882) and "A Gossip on a Novel of Dumas's" (1887) imply that it is better to entertain than to instruct. Stevenson very much saw himself in the mould of Sir Walter Scott, a storyteller with an ability to transport his readers away from themselves and their circumstances. He took issue with what he saw as the tendency in French realism to dwell on sordidness and ugliness. In "The Lantern-Bearer" (1888) he appears to takeEmile Zola

Emile or Émile may refer to:

* Émile (novel) (1827), autobiographical novel based on Émile de Girardin's early life

* Emile, Canadian film made in 2003 by Carl Bessai

* '' Emile: or, On Education'' (1762) by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a treatise o ...

to task for failing to seek out nobility in his protagonists.

In "A Humble Remonstrance", Stevenson answers Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

's claim in "The Art of Fiction" (1884) that the novel competes with life. Stevenson protests that no novel can ever hope to match life's complexity; it merely abstracts from life to produce a harmonious pattern of its own.Man's one method, whether he reasons or creates, is to half-shut his eyes against the dazzle and confusion of reality...Life is monstrous, infinite, illogical, abrupt and poignant; a work of art, in comparison, is neat, finite, self-contained, rational, flowing, and emasculate...The novel, which is a work of art, exists, not by its resemblances to life, which are forced and material ... but by its immeasurable difference from life, which is designed and significant.It is not clear, however, that in this there was any real basis for disagreement with James. Stevenson had presented James with a copy of ''Kidnapped'', but it was ''Treasure Island'' that James favoured. Written as a story for boys, Stevenson had thought it in "no need of psychology or fine writing", but its success is credited with liberating children's writing from the "chains of Victorian

didacticism

Didacticism is a philosophy that emphasises instructional and informative qualities in literature, art, and design. In art, design, architecture, and landscape, didacticism is a conceptual approach that is driven by the urgent need to explain.

...

".

Politics: "The Day After Tomorrow"

During his college years, Stevenson briefly identified himself as a "red-hot socialist". But already by age 26 he was writing of looking back on this time "with something like regret. ... Now I know that in thus turning Conservative with years, I am going through the normal cycle of change and travelling in the common orbit of men's opinions." His cousin and biographer Sir Graham Balfour claimed that Stevenson "probably throughout life would, if compelled to vote, have always supported the Conservative candidate." In 1866, then 15-year-old Stevenson did vote for

During his college years, Stevenson briefly identified himself as a "red-hot socialist". But already by age 26 he was writing of looking back on this time "with something like regret. ... Now I know that in thus turning Conservative with years, I am going through the normal cycle of change and travelling in the common orbit of men's opinions." His cousin and biographer Sir Graham Balfour claimed that Stevenson "probably throughout life would, if compelled to vote, have always supported the Conservative candidate." In 1866, then 15-year-old Stevenson did vote for Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, the Tory democrat and future Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, for the Lord Rectorship of the University of Edinburgh. But this was against a markedly illiberal challenger, the historian Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

. Carlyle was notorious for his anti-democratic and pro-slavery views.

In "The Day After Tomorrow", appearing in ''The Contemporary Review'' (April 1887), Stevenson suggested: "we are all becoming Socialists without knowing it". Legislation "grows authoritative, grows philanthropical, bristles with new duties and new penalties, and casts a spawn of inspectors, who now begin, note-book in hand, to darken the face of England". He is referring to the steady growth in social legislation in Britain since the first of the Conservative-sponsored Factory Acts

The Factory Acts were a series of acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom beginning in 1802 to regulate and improve the conditions of industrial employment.

The early acts concentrated on regulating the hours of work and moral wel ...

(which, in 1833, established a professional Factory Inspectorate). Stevenson cautioned that this "new waggon-load of laws" points to a future in which our grandchildren might "taste the pleasures of existence in something far liker an ant-heap than any previous human polity". Yet in reproducing the essay his latter-day libertarian admirers omit his express understanding for the abandonment of Whiggish, classical-liberal notions of laissez faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

. "Liberty", Stevenson wrote, "has served us a long while" but like all other virtues "she has taken wages". ibertyhas dutifully served Mammon; so that many things we were accustomed to admire as the benefits of freedom and common to all, were truly benefits of wealth, and took their value from our neighbour's poverty...Freedom to be desirable, involves kindness, wisdom, and all the virtues of the free; but the free man as we have seen him in action has been, as of yore, only the master of many helots; and the slaves are still ill-fed, ill-clad, ill-taught, ill-housed, insolently entreated, and driven to their mines and workshops by the lash of famine.In January 1888, aged 37, in response to American press coverage of the

Land War

The Land War () was a period of agrarian agitation in rural History of Ireland (1801–1923), Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the firs ...

in Ireland, Stevenson penned a political essay (rejected by ''Scribner's'' magazine and never published in his lifetime) that advanced a broadly conservative theme: the necessity of "staying internal violence by rigid law". Notwithstanding his title, "Confessions of a Unionist", Stevenson defends neither the union with Britain (she had "majestically demonstrated her incapacity to rule Ireland") nor "landlordism" (scarcely more defensible in Ireland than, as he had witnessed it, in the goldfields of California). Rather he protests the readiness to pass "lightly" over crimes—"unmanly murders and the harshest extremes of boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

ing"—where these are deemed "political". This he argues is to "defeat law" (which is ever a "compromise") and to invite "anarchy": it is "the sentimentalist preparing the pathway for the brute".

Final years in the Pacific

Pacific voyages

In June 1888, Stevenson chartered the yacht ''Casco'' from Samuel Merritt and set sail with his family from San Francisco. The vessel "plowed her path of snow across the empty deep, far from all track of commerce, far from any hand of help." The sea air and thrill of adventure for a time restored his health, and for nearly three years he wandered the eastern and central Pacific, stopping for extended stays at the Hawaiian Islands, where he became a good friend of King

In June 1888, Stevenson chartered the yacht ''Casco'' from Samuel Merritt and set sail with his family from San Francisco. The vessel "plowed her path of snow across the empty deep, far from all track of commerce, far from any hand of help." The sea air and thrill of adventure for a time restored his health, and for nearly three years he wandered the eastern and central Pacific, stopping for extended stays at the Hawaiian Islands, where he became a good friend of King Kalākaua

Kalākaua (David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua; November 16, 1836 – January 20, 1891), was the last king and penultimate monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, reigning from February 12, 1874, u ...

. He befriended the king's niece Princess Victoria Kaiulani, who also had Scottish heritage. He spent time at the Gilbert Islands

The Gilbert Islands (;Reilly Ridgell. ''Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.'' 3rd. Ed. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95. formerly Kingsmill or King's-Mill IslandsVery often, this name applied o ...

, Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

, New Zealand and the Samoan Islands

The Samoan Islands () are an archipelago covering in the central Pacific Ocean, South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Political geography, Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Samoa, Indep ...

. During this period, he completed ''The Master of Ballantrae

''The Master of Ballantrae: A Winter's Tale'' is an 1889 novel by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson, focusing upon the conflict between two brothers, Scottish noblemen whose family is torn apart by the Jacobite rising of 1745. He wo ...

'', composed two ballads based on the legends of the islanders, and wrote '' The Bottle Imp''. He preserved the experience of these years in his various letters and in his ''In the South Seas'' (which was published posthumously). He made a voyage in 1889 with Lloyd on the trading schooner ''Equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

'', visiting Butaritari

Butaritari is an atoll in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on th ...

, Mariki, Apaiang and Abemama in the Gilbert Islands

The Gilbert Islands (;Reilly Ridgell. ''Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.'' 3rd. Ed. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95. formerly Kingsmill or King's-Mill IslandsVery often, this name applied o ...

.''In the South Seas'' (1896)& (1900) Chatto & Windus; republished by The Hogarth Press (1987) They spent several months on Abemama with tyrant-chief Tem Binoka, whom Stevenson described in ''In the South Seas''.

Stevenson left Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

, Australia, on the ''Janet Nicoll'' in April 1890 for his third and final voyage among the South Seas islands.''The Cruise of the Janet Nichol Among the South Sea Islands''Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson,

Charles Scribner's Sons

Charles Scribner's Sons, or simply Scribner's or Scribner, is an American publisher based in New York City that has published several notable American authors, including Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kurt Vonnegut, Marjori ...

, New York, 1914 He intended to produce another book of travel writing to follow his earlier book ''In the South Seas'', but it was his wife who eventually published her journal of their third voyage. (Fanny misnames the ship in her account ''The Cruise of the Janet Nichol''.) A fellow passenger was Jack Buckland, whose stories of life as an island trader became the inspiration for the character of Tommy Hadden in '' The Wrecker'' (1892), which Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne wrote together.Selected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson, ed. by Ernest Mehew (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2001) p. 418, n. 3 Buckland visited the Stevensons at Vailima in 1894.

Political engagement in Samoa

In December 1889, 39-year-old Stevenson and his extended family arrived at the port of Apia in the Samoan islands and there he and Fanny decided to settle. In January 1890 they purchased at Vailima, some miles inland from Apia the capital, on which they built the islands' first two-storey house. Fanny's sister, Nellie Van de Grift Sanchez, wrote that "it was in Samoa that the word 'home' first began to have a real meaning for these gypsy wanderers". In May 1891, they were joined by Stevenson's mother, Margaret. While his wife set about managing and working the estate, 40-year-old Stevenson took the native name Tusitala (Samoan for "Teller of Tales"), and began collecting local stories. Often he would exchange these for his own tales. The first work of literature in Samoan was his translation of '' The Bottle Imp (1891)'', which presents a Pacific-wide community as the setting for a moral fable. Immersing himself in the islands' culture, occasioned a "political awakening": it placed Stevenson "at an angle" to the rivalgreat power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

s, Britain, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and the United States whose warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is used for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the navy branch of the armed forces of a nation, though they have also been operated by individuals, cooperatives and corporations. As well as b ...

s were common sights in Samoan harbours. He understood that, as in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands (; , ) is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Scottish Lowlands, Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Scots language, Lowland Scots language replaced Scottish Gae ...

(comparisons with his homeland "came readily"), an indigenous clan society was unprepared for the arrival of foreigners who played upon its existing rivalries and divisions. As the external pressures upon Samoan society grew, tensions soon descended into several inter-clan wars.Jenni Calder, Introduction,

No longer content to be a "romancer", Stevenson became a reporter and an agitator, firing off letters to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' which "rehearsed with an ironic twist that surely owed something to his Edinburgh legal training", a tale of European and American misconduct. His concern for the Polynesians

Polynesians are an ethnolinguistic group comprising closely related ethnic groups native to Polynesia, which encompasses the islands within the Polynesian Triangle in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sout ...

is also found in the ''South Sea Letters'', published in magazines in 1891 (and then in book form as ''In the South Seas'' in 1896). In an effort he feared might result in his own deportation, Stevenson helped secure the recall of two European officials. '' A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa'' (1892) was a detailed chronicle of the intersection of rivalries between the great powers and the first Samoan Civil War.

As much as he said he disdained politics—"I used to think meanly of the plumber", he wrote to his friend Sidney Colvin, "but how he shines beside the politician!"—Stevenson felt himself obliged to take sides. He openly allied himself with chief Mataafa, whose rival Malietoa was backed by the Germans whose firms were beginning to monopolise copra

Copra (from ; ; ; ) is the dried, white flesh of the coconut from which coconut oil is extracted. Traditionally, the coconuts are sun-dried, especially for export, before the oil, also known as copra oil, is pressed out. The oil extracted ...

and cocoa bean processing.

Stevenson was alarmed above all by what he perceived as the Samoans' economic innocence—their failure to secure their claim to proprietorship of the land (in a Lockean

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 ( O.S.) – 28 October 1704 ( O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Con ...

sense) through improving management and labour. In 1894 just months before his death, he addressed the island chiefs:There is but one way to defend Samoa. Hear it before it is too late. It is to make roads, and gardens, and care for your trees, and sell their produce wisely, and, in one word, to occupy and use your country... if you do not occupy and use your country, others will. It will not continue to be yours or your children's, if you occupy it for nothing. You and your children will, in that case, be cast out into outer darkness".He had "seen these judgments of God", not only in Hawaii where abandoned native churches stood like tombstones "over a grave, in the midst of the white men's sugar fields", but also in Ireland and "in the mountains of my own country Scotland".

These were a fine people in the past brave, gay, faithful, and very much like Samoans, except in one particular, that they were much wiser and better at that business of fighting of which you think so much. But the time came to them as it now comes to you, and it did not find them ready...Five years after Stevenson's death, the Samoan Islands were partitioned between Germany and the United States.

Last works

Stevenson wrote an estimated 700,000 words during his years on Samoa. He completed '' The Beach of Falesá'', the first-person tale of a Scottish

Stevenson wrote an estimated 700,000 words during his years on Samoa. He completed '' The Beach of Falesá'', the first-person tale of a Scottish copra

Copra (from ; ; ; ) is the dried, white flesh of the coconut from which coconut oil is extracted. Traditionally, the coconuts are sun-dried, especially for export, before the oil, also known as copra oil, is pressed out. The oil extracted ...

trader on a South Sea island, a man unheroic in his actions or his own soul. Rather he is a man of limited understanding and imagination, comfortable with his own prejudices: where, he wonders, can he find "whites" for his "half caste" daughters. The villains are white, their behaviour towards the islanders ruthlessly duplicitous.

Stevenson saw "The Beach of Falesá" as the ground-breaking work in his turn away from romance to realism. Stevenson wrote to his friend Sidney Colvin:

'' The Ebb-Tide'' (1894), the misadventures of three deadbeats marooned in the Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

an port of Papeete

Papeete (Tahitian language, Tahitian: ''Papeʻetē'', pronounced ; old name: ''Vaiʻetē''Personal communication with Michael Koch in ) is the capital city of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of the France, French Republic in the Pacific ...

, has been described as presenting "a microcosm of imperialist society, directed by greedy but incompetent whites, the labour supplied by long-suffering natives who fulfil their duties without orders and are true to the missionary faith which the Europeans make no pretence of respecting".Roslyn Jolly, "Introduction" in ''Robert Louis Stevenson: South Sea Tales'' (1996) It confirmed the new Realistic turn in Stevenson's writing away from romance and adolescent adventure. The first sentence reads: "Throughout the island world of the Pacific, scattered men of many European races and from almost every grade of society carry activity and disseminate disease". No longer was Stevenson writing about human nature "in terms of a contest between Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde": "the edges of moral responsibility and the margins of moral judgement were too blurred". As with ''The Beach of Falesà'', in ''The Ebb Tide'' contemporary reviewers find parallels with several of Conrad's works: '' Almayer's Folly'', '' An Outcast of the Islands'', ''The Nigger of the 'Narcissus'

''The'' is a grammatical article in English, denoting nouns that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The ...

, ''Heart of Darkness

''Heart of Darkness'' is an 1899 novella by Polish-British novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgium, Belgian company in the African interior. Th ...

'', and '' Lord Jim''.

With his imagination still residing in Scotland and returning to earlier form, Stevenson also wrote ''Catriona

Catriona is a feminine given name in the English language. It is an Anglicisation of the Irish Caitríona or Scottish Gaelic Catrìona, which are forms of the English Katherine

Katherine (), also spelled Catherine and Catherina, other var ...

'' (1893), a sequel to his earlier novel '' Kidnapped'' (1886), continuing the adventures of its hero David Balfour.

Although he felt, as a writer, that "there was never any man had so many irons in the fire". by the end of 1893 Stevenson feared that he had "overworked" and exhausted his creative vein. His writing was partly driven by the need to meet the expenses of Vailima. But in a last burst of energy he began work on '' Weir of Hermiston''. "It's so good that it frightens me," he is reported to have exclaimed. He felt that this was the best work he had done. Set in eighteenth century Scotland, it is a story of a society that (however different), like Samoa is witnessing a breakdown of social rules and structures leading to growing moral ambivalence.

Death

On 3 December 1894, Stevenson was talking to his wife and straining to open a bottle of wine when he suddenly exclaimed, "What's that?", then asked his wife, "Does my face look strange?", and collapsed.Balfour, Graham (1906).The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson