Robert Knox on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Knox (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in the Burke and Hare murders. Born in

Knox returned to Edinburgh by Christmas 1822. On 1 December 1823 he was elected a Fellow of the

Knox returned to Edinburgh by Christmas 1822. On 1 December 1823 he was elected a Fellow of the

As a consequence,

As a consequence,

Knox left for London after the death of his wife (the remaining children were left with a nephew). He found it impossible to find a university post, and from then until 1856 he worked on medical journalism, gave public lectures, and wrote several books, including his most ambitious work, ''The Races of Men'' in which he argued that each race was suited to its environment and "perfect in its own way." His book about fishing sold best. In 1854 his son Robert died of heart disease; Knox tried for a posting to the Crimea but at 63 was judged too old.

In 1856 he became the pathological

Knox left for London after the death of his wife (the remaining children were left with a nephew). He found it impossible to find a university post, and from then until 1856 he worked on medical journalism, gave public lectures, and wrote several books, including his most ambitious work, ''The Races of Men'' in which he argued that each race was suited to its environment and "perfect in its own way." His book about fishing sold best. In 1854 his son Robert died of heart disease; Knox tried for a posting to the Crimea but at 63 was judged too old.

In 1856 he became the pathological

*An Amazon original anthology television series Lore features Burke and Hare murders case in its Season 2 episode 1 named " Burke and Hare: In the Name of Science" released on October 19, 2018.

*

*An Amazon original anthology television series Lore features Burke and Hare murders case in its Season 2 episode 1 named " Burke and Hare: In the Name of Science" released on October 19, 2018.

*

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Knox eventually partnered with anatomist and former teacher John Barclay and became a lecturer on anatomy in the city, where he introduced the theory of transcendental anatomy

Transcendental anatomy, also known as philosophical anatomy, was a form of comparative anatomy that sought to find ideal patterns and structures common to all organisms in nature. The term originated from naturalist philosophy in the German provin ...

. However, Knox's incautious methods of obtaining cadavers for dissection before the passage of the Anatomy Act 1832 and disagreements with professional colleagues ruined his career in Scotland. Following these developments, he moved to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, though this did not revive his career.

Knox's views on humanity gradually shifted over the course of his lifetime, as his initially positive views (influenced by the ideals of Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theories ...

) gave way to a more pessimistic view. Knox also devoted the latter part of his career to studying and theorising on evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

and ethnology

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology). ...

; during this period, he also wrote numerous works advocating scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

. His work on the latter further harmed his legacy and overshadowed his contributions to evolutionary theory

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

, which he used to account for racial differences.

Life

Early life

Robert Knox was born in 1791 in Edinburgh's North Richmond Street, the eighth child of Mary (née Scherer) and Robert Knox (d. 1812), a teacher of mathematics andnatural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancien ...

at Heriot's Hospital

George Heriot's School is a Scottish independent primary and secondary day school on Lauriston Place in the Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. In the early 21st century, it has more than 1600 pupils, 155 teaching staff, and 80 non-teaching staff. ...

in Edinburgh. As an infant, he contracted smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, which destroyed his left eye and disfigured his face. He was educated at the Royal High School of Edinburgh

The Royal High School (RHS) of Edinburgh is a co-educational school administered by the City of Edinburgh Council. The school was founded in 1128 and is one of the oldest schools in Scotland. It serves 1,200 pupils drawn from four feeder prim ...

, where he was remembered as a 'bully' who thrashed his contemporaries "mentally and corporeally". He won the Lord Provost's gold medal in his final year.

In 1810, he joined medical classes at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1 ...

. He soon became interested in transcendentalism and the work of Xavier Bichat

Marie François Xavier Bichat (; ; 14 November 1771 – 22 July 1802) was a French anatomist and pathologist, known as the father of modern histology. Although he worked without a microscope, Bichat distinguished 21 types of elementary tissues ...

. He was twice president of the Royal Physical Society, an undergraduate club to which he presented papers on hydrophobia and nosology

Nosology () is the branch of medical science that deals with the classification of diseases. Fully classifying a medical condition requires knowing its cause (and that there is only one cause), the effects it has on the body, the symptoms that ...

. The final recorded event of his university years was his just failing the anatomy examination. Knox joined the "extramural" anatomy class of the famous John Barclay. Barclay was an anatomist of the highest distinction, and perhaps the greatest anatomical teacher in Britain at that time. Redoubling his efforts, Knox passed competently the second time around.

Life abroad

Knox graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 1814, with a Latin thesis on the effects ofnarcotics

The term narcotic (, from ancient Greek ναρκῶ ''narkō'', "to make numb") originally referred medically to any psychoactive compound with numbing or paralyzing properties. In the United States, it has since become associated with opiate ...

which was published the following year. He joined the army and was commissioned Hospital Assistant on 24 June 1815, after having studied for a year under John Abernethy at St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (die ...

in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. He was sent immediately to Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

to attend the wounded from the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armies of the Sevent ...

and returned two weeks later with the first batch of wounded aboard a hospital ship; during the voyage he successfully employed Abernethy's technique of leaving wounds open to the air. His army work at the Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

military hospital (near Waterloo) impressed upon him the need for a comprehensive training in anatomy if surgery were to be successful. Knox was intelligent, critical and irritable. He did not suffer fools gladly and—in an aside with terrible consequences for his future career—he was critical of the surgical work of Charles Bell

Sir Charles Bell (12 November 177428 April 1842) was a Scottish surgeon, anatomist, physiologist, neurologist, artist, and philosophical theologian. He is noted for discovering the difference between sensory nerves and motor nerves in the spin ...

with casualties at the Battle of Waterloo. After a further trip to Belgium he was placed in charge of Hilsea hospital near Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

, where he experimented with non-mercurial cures for syphilis.

In April 1817, he joined the 72nd Highlanders

The 72nd Highlanders was a British Army Highland Infantry Regiment of the Line. Raised in 1778, it was originally numbered 78th, before being redesignated the 72nd in 1786. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 78th (Highlanders) ...

and sailed with them to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

. There were few army surgeons in the Cape Colony but Knox found the people healthy and his duties were light. He enjoyed riding, shooting and the beauty of the landscape with which he felt in spiritual harmony—an early expression of his transcendental world view. Knox developed an interest in observing racial types, and disapproved of what he saw as the Boers

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this a ...

' contempt for the indigenous peoples. However, after an abortive Xhosa rebellion against the colonial forces, he was involved in a retaliatory raid commanded by Andries Stockenström

Sir Andries Stockenström, 1st Baronet, (6 July 1792 in Cape Town – 16 March 1864 in London) was lieutenant governor of British Kaffraria from 13 September 1836 to 9 August 1838.

His efforts in restraining colonists from moving into Xhosa ...

, a magistrate and future Lieutenant Governor. Relations with Stockenström were marred when Knox accused O. G. Stockenström, Andries' brother, of theft, a charge apparently prompted by ill feeling between British and Boer officers. A court martial acquitted O. G. of the charge and Andries called Knox's conduct shameful. One of Stockenström's supporters, a former naval officer named Burdett, challenged Knox to a duel. Knox initially refused to fight, and Burdett "soundly horse whipped him on the parade before every Officer of the Garrison." Knox then grabbed a sabre and inflicted a slight wound to Burdett's arm. Knox's promotion to Assistant Surgeon was cancelled and he returned to Britain in disgrace, arriving on Christmas Day 1820. He remained only until the following October, after which he went to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

to study anatomy for just over a year (1821–22). It was then that he met both Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theories ...

, who were to remain his heroes for the rest of life, to populate his later medical journalism, and to become the subject of his hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies might ...

, ''Great artists and great anatomists''. While in Paris he befriended Thomas Hodgkin

Thomas Hodgkin RMS (17 August 1798 – 5 April 1866) was a British physician, considered one of the most prominent pathologists of his time and a pioneer in preventive medicine. He is now best known for the first account of Hodgkin's disease, ...

, with whom he shared a dissecting room at l' Hôpital de la Pitié.

Career in Edinburgh

Knox returned to Edinburgh by Christmas 1822. On 1 December 1823 he was elected a Fellow of the

Knox returned to Edinburgh by Christmas 1822. On 1 December 1823 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

. During these years he communicated a number of well-received papers to the Royal and Wernerian societies of Edinburgh on zoological subjects. Soon after his election he submitted a plan to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) is a professional organisation of surgeons. The College has seven active faculties, covering a broad spectrum of surgical, dental, and other medical practices. Its main campus is located o ...

for a Museum of Comparative Anatomy, which was accepted, and on 13 January 1825 he was appointed curator of the museum with a salary of £100.

In 1825, John Barclay offered him a partnership at his anatomy school in Surgeon's Square, Edinburgh. In order for his lectures to be recognised by the Edinburgh College of Surgeons, Knox had to be admitted to its fellowship; a formality, but, at £250, an expensive one. At this time most professorships were in the gift of the town council, resulting in such uninspiring teachers as the professor of anatomy Alexander Monro, who put off many of his students (including the young Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

who took the course 1825–1827). This created a demand for private tuition, and the flamboyant Knox—in sole charge after Barclay's death in 1826—had more students than all the other private tutors put together.

He turned his sharp wit on the elders and the clergy of the city, satirising religion and delighting his students. Knox routinely referred to the Bridgewater Treatises as the "bilgewater treatises" and his 'continental' lectures were not for the squeamish. John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin; April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was an American self-trained artist, naturalist, and ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornithology turned into a plan to make a complete pictori ...

was in Edinburgh at the time to find subscribers for his '' Birds of America''. Shown round the dissecting theatre by Knox, "dressed in an overgown and with bloody fingers", Audubon reported that "The sights were extremely disagreeable, many of them shocking beyond all I ever thought could be. I was glad to leave this charnel house and breathe again the salubrious atmosphere of the streets". Knox's school flourished and he took on three assistants, Alexander Miller, Thomas Wharton Jones

Thomas Wharton Jones (9 January 1808 – 7 November 1891) was an eminent ophthalmologist and physiologist of the 19th century.

Biography

Jones's father was Richard Jones, a native of London. Richard Jones had moved north to St. Andrews and was ...

and William Fergusson.

Marriage and personal life

Little is known of Knox's wife, Susan Knox, whom he married in 1824. According to Knox's friend Henry Lonsdale the marriage was kept secret as she was 'of inferior rank.' During his time in Edinburgh, Knox lived at 4 Newington Place with his sisters Mary and Jessie, while Susan and his four children lived at Lilliput Cottage in Trinity, west ofLeith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

. They had seven children, but only two of them survived into adulthood.

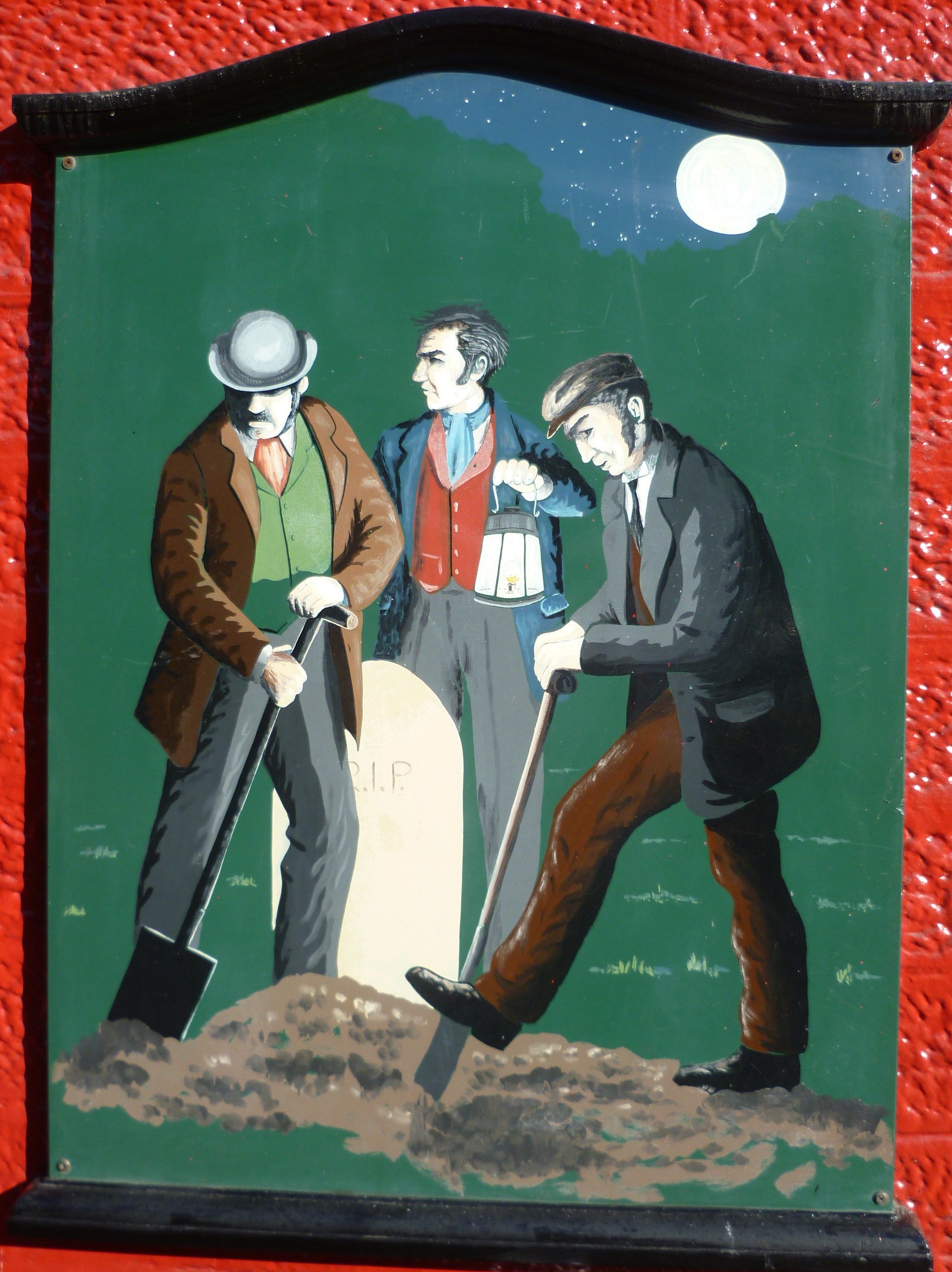

West Port murders

Before theAnatomy Act

The Anatomy Act 1832 (2 & 3 Will. IV c.75) is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that gave free licence to doctors, teachers of anatomy and bona fide medical students to dissect donated bodies. It was enacted in response to public rev ...

of 1832 widened the supply, the main legal supply of corpses for anatomical purposes in the UK were those condemned to death and dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

by the courts. This led to a chronic shortage of legitimate subjects for dissection, and this shortage became more serious as the need to train medical students grew, and the number of executions fell. In his school Knox ran up against the problem from the start, since—after 1815—the Royal Colleges had increased the anatomical work in the medical curriculum. If he taught according to what was known as 'French method' the ratio would have had to approach one corpse per pupil.

body-snatching

Body snatching is the illicit removal of corpses from graves, morgues, and other burial sites. Body snatching is distinct from the act of grave robbery as grave robbing does not explicitly involve the removal of the corpse, but rather theft from ...

became so prevalent that it was not unusual for relatives and friends of someone who had just died to watch over the body until burial, and then to keep watch over the grave after burial, to stop it being violated.

In November 1827, William Hare began a new career when an indebted lodger died on him by chance. He was paid £7.10s (seven pounds & ten shillings) for delivering the body to Knox's dissecting rooms at Surgeons' Square. Now Hare and his accomplice, William Burke, set about murdering the city’s poor on a regular basis. After 16 more transactions, each netting £8-10, in what later became known as the West Port Murders

The Burke and Hare murders were a series of sixteen killings committed over a period of about ten months in 1828 in Edinburgh, Scotland. They were undertaken by William Burke and William Hare, who sold the corpses to Robert Knox for dissectio ...

, on 2 November 1828 Burke and Hare were caught, and the whole city convulsed with horror, fed by ballads, broadsides, and newspapers, at the reported deeds of the pair. Hare turned King's evidence, and Burke was hanged, dissected and his remains displayed.

Knox was not prosecuted, which outraged many in Edinburgh. His house was attacked by a mob of 'the lowest rabble of the Old Town,' and windows were broken. A committee of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

exonerated him on the grounds that he had not dealt personally with Burke and Hare, but there was no forgetting his part in the case, and many remained wary of him.

Almost immediately after the Burke and Hare case, the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) is a professional organisation of surgeons. The College has seven active faculties, covering a broad spectrum of surgical, dental, and other medical practices. Its main campus is located o ...

began to harry him, and by June 1831 they had procured his resignation as the Curator of the museum he had proposed and founded. In the same year he was obliged to resign his army commission to avoid further service in the Cape. This removed his last source of guaranteed income, but fortunately his classes were more popular than ever, with a record 504 students. His school moved to the grander premises of Old Surgeons' Hall in 1833 but his class declined after Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted ...

made its own practical anatomy class compulsory in the mid-1830s. Knox continued to purchase cadavers for his dissection class from such shadowy figures as the 'Black Bull Man,' but after the 1832 Anatomy Act made bodies more available to all anatomists, he quarrelled with HM Inspector of Anatomy over the supply of bodies, and his competitive edge was lost. In 1837 Knox applied for the chair in pathology at Edinburgh University but his candidature was blocked by eleven existing professors, who preferred to abolish the post rather than appoint him. In 1842 he was unable to make payments to the Edinburgh funeratory system, from which bodies were supplied to private schools, and he relocated to Glasgow where, still short of subjects for dissection, he closed his school in 1844. In 1847 the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh found him guilty of falsifying a student's certificate of attendance (a not uncommon practice in private schools) and refused to accept any further certificates from him, effectively banning him from teaching in Scotland. In the same year he was expelled from the Royal Society of Edinburgh and had his election retrospectively cancelled.

London

Knox left for London after the death of his wife (the remaining children were left with a nephew). He found it impossible to find a university post, and from then until 1856 he worked on medical journalism, gave public lectures, and wrote several books, including his most ambitious work, ''The Races of Men'' in which he argued that each race was suited to its environment and "perfect in its own way." His book about fishing sold best. In 1854 his son Robert died of heart disease; Knox tried for a posting to the Crimea but at 63 was judged too old.

In 1856 he became the pathological

Knox left for London after the death of his wife (the remaining children were left with a nephew). He found it impossible to find a university post, and from then until 1856 he worked on medical journalism, gave public lectures, and wrote several books, including his most ambitious work, ''The Races of Men'' in which he argued that each race was suited to its environment and "perfect in its own way." His book about fishing sold best. In 1854 his son Robert died of heart disease; Knox tried for a posting to the Crimea but at 63 was judged too old.

In 1856 he became the pathological anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

to the Free Cancer Hospital, London. He joined the medical register at its inception in 1858 and practiced obstetrics in Hackney. On 27 November 1860 he was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Ethnological Society of London, where he spoke in public for the last time on 1 July 1862. He continued working at the Cancer Hospital until shortly before his death on 20 December 1862, at 9 Lambe Terrace in Hackney. He was buried at Brookwood Cemetery

Brookwood Cemetery, also known as the London Necropolis, is a burial ground in Brookwood, Surrey, England. It is the largest cemetery in the United Kingdom and one of the largest in Europe. The cemetery is listed a Grade I site in the Regi ...

near Woking, Surrey.

Ethnology and racism

Knox's interest in race began as an undergraduate. His relevant political views were radical: he was an abolitionist and anti-colonialist who criticised the Boer as "the cruel oppressor of the dark races." Knox is generally considered to be a polygenist; however, some have argued that he was a monogenist, including biographer Alan Bates, who considers such claims to be "exaggerated". In his best-selling work, ''The Races of Men'' (1850), a "Zoological history" of mankind, Knox exaggerated supposed racial differences in support of his project, asserting that, anatomically and behaviourally, "race, or hereditary descent, is everything". He offered crude characterisations of each racial group: for example the Saxon (in which race he included himself) "invents nothing", "has no musical ear", lacks "genius", and is so "low and boorish" that "he does not know what you mean by fine art". No race was without its redeeming features, however; Knox described Saxons as " oughtful, plodding, industrious beyond all other races, nda lover of labour for labour's sake". Such supposed racial characteristics meant that each race was naturally fitted for a particular environment and could not endure outside of it. While Knox maintained that all races were capable of some form of civilized life, he maintained that a vast gulf stood between the limited attainments available to the 'negroid' and to most 'mongoloid' races on one hand and the much greater past achievements and future potential of white men on the other. The Black, Knox remarked, 'is no more a white man than an ass is a horse or a zebra'. Ultimately however, all races were " stined ... to run, like all other animals, a certain limited course of existence", it mattering "little how their extinction is brought about". In 1862 Knox took the opportunity of a second edition of ''The Races of Men'' to defend the "much maligned races" of the Cape against accusations of cannibalism, and to rebuke the Dutch for treating them like "wild beasts". From the perspective of a Lowland Scot Protestant, Knox's racist works espoused extreme racial hostility toCelts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

in general (including the Highland Scots

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland S ...

and Welsh people

The Welsh ( cy, Cymry) are an ethnic group native to Wales. "Welsh people" applies to those who were born in Wales ( cy, Cymru) and to those who have Welsh ancestry, perceiving themselves or being perceived as sharing a cultural heritage and ...

, but particularly the Irish people

The Irish ( ga, Muintir na hÉireann or ''Na hÉireannaigh'') are an ethnic group and nation native to the island of Ireland, who share a common history and culture. There have been humans in Ireland for about 33,000 years, and it has bee ...

). He considered the "Caledonian Celt" as touching "the end of his career: they are reduced to about one hundred and fifty thousand" and that the "Welsh Celts are not troublesome, but might easily become so." For Knox, "the Irish Celt is the most to be dreaded" and openly advocated their ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

around the time that the Great Famine was happening, stating in ''The Races of Men: A Fragment'' (1850): "The source of all evil lies in the race, the Celtic race of Ireland. There is no getting over historical facts. Look at Wales, look at Caledonia; it is ever the same. ..The race must be forced from the soil; by fair means, if possible; still they must leave. The Orange club of Ireland is a Saxon confederation for the clearing the land of all Papists and Jacobites

Jacobite means follower of Jacob or James. Jacobite may refer to:

Religion

* Jacobites, followers of Saint Jacob Baradaeus (died 578). Churches in the Jacobite tradition and sometimes called Jacobite include:

** Syriac Orthodox Church, sometimes ...

; this means Celts. If left to themselves, they would clear them out, as Cromwell proposed, by the sword; it would not require six weeks to accomplish the work. But the Encumbered Estates Relief Bill will do it better."

Transcendentalism

In his writings Knox synthesised a perspective on nature from three of the most influential natural historians of his time. From Cuvier, he took a consciousness of the great epochs of time, of the fact of extinction, and of the inadequacy of the biblical account. From Étienne Geoffroy St-Hilaire and Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville, he gained a spatial and thematic perspective on living things. If one had the skill, all living beings could be arranged in their correct placing in a notional table, and one would see both internally and externally the elegant variation of their organs and anatomy according to the principles of connection, unity of composition and compensation.Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

is another crucial addition to the Knoxian way of looking at nature. Goethe thought that there were transcendental archetypes in the living world which could be perceived by genus. If the natural historian were perspicacious enough to examine the creatures in this correct order he could perceive—aesthetically—the archetype that was immanent in the totality of a series, although present in none of them.

Knox wrote that he was concerned to prove the existence of a generic animal, "or in other terms, proving hereditary descent to have a relation primarily to genus or natural family". This way, he could lay claim to a stability in the natural order at the level of the genus, but let species be extinguished. Man was a genus; not a species.

Evolution

According to Richards, ''The Races of Men'' advocated "a common material origin of life and its evolution by a process of saltatory descent"; that is to say, new species arose not by gradual change but by sudden leaps due to shifts in embryonic development. Knox tentatively concluded that "simple animals ... may have produced by continuous generation the more complex animals of after ages . . . the fish of the early world may have produced reptiles, then again birds and quadrupeds; lastly, man himself?" Newly formed species survived or perished according to external conditions, which acted as "potent checks to an infinite variety of forms". For one contemporary reviewer, his claim that "Species is the product of external circumstances, acting through millions of years" was "bold, disgusting, and gratuitous atheism." In modern terms, he proposed a theory of saltatory evolution, in which "deformations" in embryonic development produced "hopeful monsters" that, if fortuitously suited to the prevailing environmental conditions, gave rise to new species in a single, macroevolutionary leap. In 1857 he wrote: "The conversion of one of these species into another cannot be so difficult a matter with Nature, especially when all or most of the specific characters are already present in the young. Thus a given species may perish, but another of the same consanguinité takes its place in space: it is a question of time... Thus parenté extends from species to genus and from genus to class and order, in characters not to be misunderstood."Legacy

Knox is commemorated in the scientific name of a species of African lizard, '' Meroles knoxii''.Knox in fiction

*An Amazon original anthology television series Lore features Burke and Hare murders case in its Season 2 episode 1 named " Burke and Hare: In the Name of Science" released on October 19, 2018.

*

*An Amazon original anthology television series Lore features Burke and Hare murders case in its Season 2 episode 1 named " Burke and Hare: In the Name of Science" released on October 19, 2018.

*Peter Cushing

Peter Wilton Cushing (26 May 1913 – 11 August 1994) was an English actor. His acting career spanned over six decades and included appearances in more than 100 films, as well as many television, stage, and radio roles. He achieved recognition ...

plays Knox in '' The Flesh and the Fiends'' (1960). Written and directed by John Gilling, the film is a reasonably accurate depiction, allowing for some dramatic licence and time constraints, of the Burke and Hare story.

*''The Anatomist'' (1961), a British film, starred Alastair Sim as Knox. This was based on a 1930 play of the same name by James Bridie

James Bridie (3 January 1888 in Glasgow – 29 January 1951 in Edinburgh) was the pseudonym of a Scottish playwright, screenwriter and physician whose real name was Osborne Henry Mavor.Daniel Leary (1982) ''Dictionary of Literary Biography: ...

, which the BBC broadcast in 1939 with Knox played by Andrew Cruickshank

Andrew John Maxton Cruickshank (25 December 1907 in Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire29 April 1988 in London) was a Scottish actor, most famous for his portrayal of Dr Cameron in the long-running UK BBC television series '' Dr. Finlay's Casebook'', whi ...

and in 1980 with Patrick Stewart

Sir Patrick Stewart (born 13 July 1940) is an English actor who has a career spanning seven decades in various stage productions, television, film and video games. He has been nominated for Olivier, Tony, Golden Globe, Emmy, and Screen Actors ...

as Knox.

* John Hoyt played Knox in an episode of the '' Alfred Hitchcock Hour'' based on the Burke and Hare murders.

*The character Thomas Rock in the Dylan Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems " Do not go gentle into that good night" and " And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Und ...

play ''The Doctor and the Devils'' is based on Knox. The play was filmed in 1985 with Timothy Dalton

Timothy Leonard Dalton Leggett (; born 21 March 1946) is a British actor. Beginning his career on stage, he made his film debut as Philip II of France in the 1968 historical drama '' The Lion in Winter''. He gained international prominence a ...

as Dr Rock.

*Knox was the model for the character of Dr. Thomas Potter in Matthew Kneale's epic novel ''English Passengers'', which deals with the perceptions and perspectives of different races, nationalities and stations in society.

*The Knox scandal forms the background of Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as '' Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

's short story "The Body Snatcher

"The Body Snatcher" is a short story by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894). First published in ''The Pall Mall Gazette'' in December 1884, its characters were based on criminals in the employ of real-life surgeon Robert Kn ...

" (1884) The character Mr K- in the short story "The Body Snatcher" by Robert Louis Stevenson, is clearly a reference for Robert Knox. Later filmed ''The Body Snatcher

"The Body Snatcher" is a short story by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894). First published in ''The Pall Mall Gazette'' in December 1884, its characters were based on criminals in the employ of real-life surgeon Robert Kn ...

'' in 1945, starring Boris Karloff

William Henry Pratt (23 November 1887 – 2 February 1969), better known by his stage name Boris Karloff (), was an English actor. His portrayal of Frankenstein's monster in the horror film ''Frankenstein'' (1931) (his 82nd film) established ...

and Bela Lugosi

Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó (; October 20, 1882 – August 16, 1956), known professionally as Bela Lugosi (; ), was a Hungarian and American actor best remembered for portraying Count Dracula in the 1931 horror classic ''Dracula'', Ygor in ''S ...

; and TV (1966), both mentioning the West Port murders

The Burke and Hare murders were a series of sixteen killings committed over a period of about ten months in 1828 in Edinburgh, Scotland. They were undertaken by William Burke and William Hare, who sold the corpses to Robert Knox for dissectio ...

.

*In Burke & Hare, the last film of veteran director Vernon Sewell

Vernon Campbell Sewell (4 July 1903 – 21 June 2001) was a British film director, writer, producer and, briefly, an actor.

Sewell was born in London, England, and was educated at Marlborough College. He directed more than 30 films during his ...

, Knox is portrayed by Harry Andrews.

*The character Doctor Knox from manga series Fullmetal Alchemist from 2001 (which got an animation adaptation in 2009) is probably a reference to the real Robert Knox since both have the same name, physical similarities and were military surgeons specialising in autopsies and Pathologists.

*Knox is a major character in Nicola Morgan's 2003 novel "Fleshmarket"

*Leslie Phillips

Leslie Samuel Phillips (20 April 1924 – 7 November 2022) was an English actor, director, producer and author. He achieved prominence in the 1950s, playing smooth, upper-class comic roles utilising his "Ding dong" and "Hello" catchphrases. ...

played a version of Knox in the 2004 ''Doctor Who

''Doctor Who'' is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series depicts the adventures of a Time Lord called the Doctor, an extraterrestrial being who appears to be human. The Doctor explores the ...

'' audio drama '' Medicinal Purposes'', which pitted the Sixth Doctor

The Sixth Doctor is an incarnation of the Doctor, the protagonist of the BBC science fiction television series ''Doctor Who''. He is portrayed by Colin Baker. Although his televisual time on the series was comparatively brief and turbulent, Ba ...

(Colin Baker

Colin Baker (born 8 June 1943) is an English actor who played Paul Merroney in the BBC drama series '' The Brothers'' from 1974 to 1976 and the sixth incarnation of the Doctor in the long-running science fiction television series ''Docto ...

) against another time-traveller (Phillips) who had taken the place of the historical Knox, and was manipulating the events of the Burke and Hare murders.

*The ''Horrible Histories'' TV series (Series 1, Episode 13) includes a sketch about Robert Knox, in which the story of the body-snatching cases is told in a song. Knox is played by Mathew Baynton

Mathew John Baynton (born 18 November 1980) is an English actor, writer, comedian, singer, and musician best known as a member of the British Horrible Histories troupe in which he starred in the TV series '' Horrible Histories''; as well as an a ...

and Burke and Hare by Simon Farnaby and Jim Howick respectively.

*Knox was played by Tom Wilkinson in the 2010 black comedy '' Burke and Hare''

*Knox was played by Marc Wootton

Marc James Wootton (born 8 February 1975) is an English actor, comedian and writer, best known for his role as Mr Poppy in the ''Nativity!'' film series. Wootton has also appeared in ''High Spirits with Shirley Ghostman'', ''La La Land'', '' Ni ...

in Episode 2 of ''Drunk History

''Drunk History'' is an American educational comedy television series produced by Comedy Central, based on the Funny or Die web series created by Derek Waters and Jeremy Konner in 2007. They and Will Ferrell and Adam McKay are the show's ...

'' Comedy Central (2015)

*In 1942 the Dutch author Johan van der Woude published his ''Anatomie: Een Episode uit de Geschiedenis der Chirurgie'', later published as ''Schandaal om Dr Knox'', which is a historical novel about Knox and the Burke and Hare affair.

*In 1972 the TV Show Night Gallery

''Night Gallery'' is an American anthology television series that aired on NBC from December 16, 1970, to May 27, 1973, featuring stories of horror and the macabre. Rod Serling, who had gained fame from an earlier series, ''The Twilight Zone ...

(episode #70 "Deliveries in the Rear") a callous surgeon (loosely based on Knox) turns a blind eye to "resurrectionists" who murder to supply corpses for anatomy classes-until he goes insane upon finding the latest victim is his fiancé.

Works

*''Engravings of the nerves: copied from the works of Scarpa, Soemmering and other distinguished anatomists''. Edinburgh 1829. dward Mitchell, engraver*''The races of men: a fragment''. Renshaw, London. 1850, revised 1862. *''Great artists and great anatomists: a biographical and philosophical study''. Van Voorst, London 1852. *''A manual of artistic anatomy'' 1852. *''Fish and fishing in the lone glens of Scotland, with a history of the propagation, growth and metamorphoses of the Salmon''. Routledge, London 1854. *''Man – his structure and physiology'' 1857.References

Sources

* *Further reading

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Knox, Robert 19th-century British scientists 19th-century Scottish people 72nd Highlanders officers 1791 births 1862 deaths Alumni of the University of Edinburgh British Army personnel of the Napoleonic Wars British Army regimental surgeons British ethnologists Burials at Brookwood Cemetery Fellows of the Ethnological Society of London Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh Medical doctors from Edinburgh Proto-evolutionary biologists Scottish anatomists Scottish curators Scottish non-fiction writers Scottish surgeons Scottish zoologists University of Paris alumni