Robert Burns Woodward on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Burns Woodward (April 10, 1917 – July 8, 1979) was an American

Nobelprize.org Woodward's doctoral work involved investigations related to the synthesis of the female sex hormone

Culminating in the 1930s, the British chemists Christopher Ingold and Robert Robinson among others had investigated the mechanisms of organic reactions, and had come up with empirical rules which could predict reactivity of organic molecules. Woodward was perhaps the first synthetic organic chemist who used these ideas as a predictive framework in synthesis. Woodward's style was the inspiration for the work of hundreds of successive synthetic chemists who synthesized medicinally important and structurally complex natural products.

Culminating in the 1930s, the British chemists Christopher Ingold and Robert Robinson among others had investigated the mechanisms of organic reactions, and had come up with empirical rules which could predict reactivity of organic molecules. Woodward was perhaps the first synthetic organic chemist who used these ideas as a predictive framework in synthesis. Woodward's style was the inspiration for the work of hundreds of successive synthetic chemists who synthesized medicinally important and structurally complex natural products.

Robert M. Williams

(Colorado State), Harry Wasserman (Yale),

link

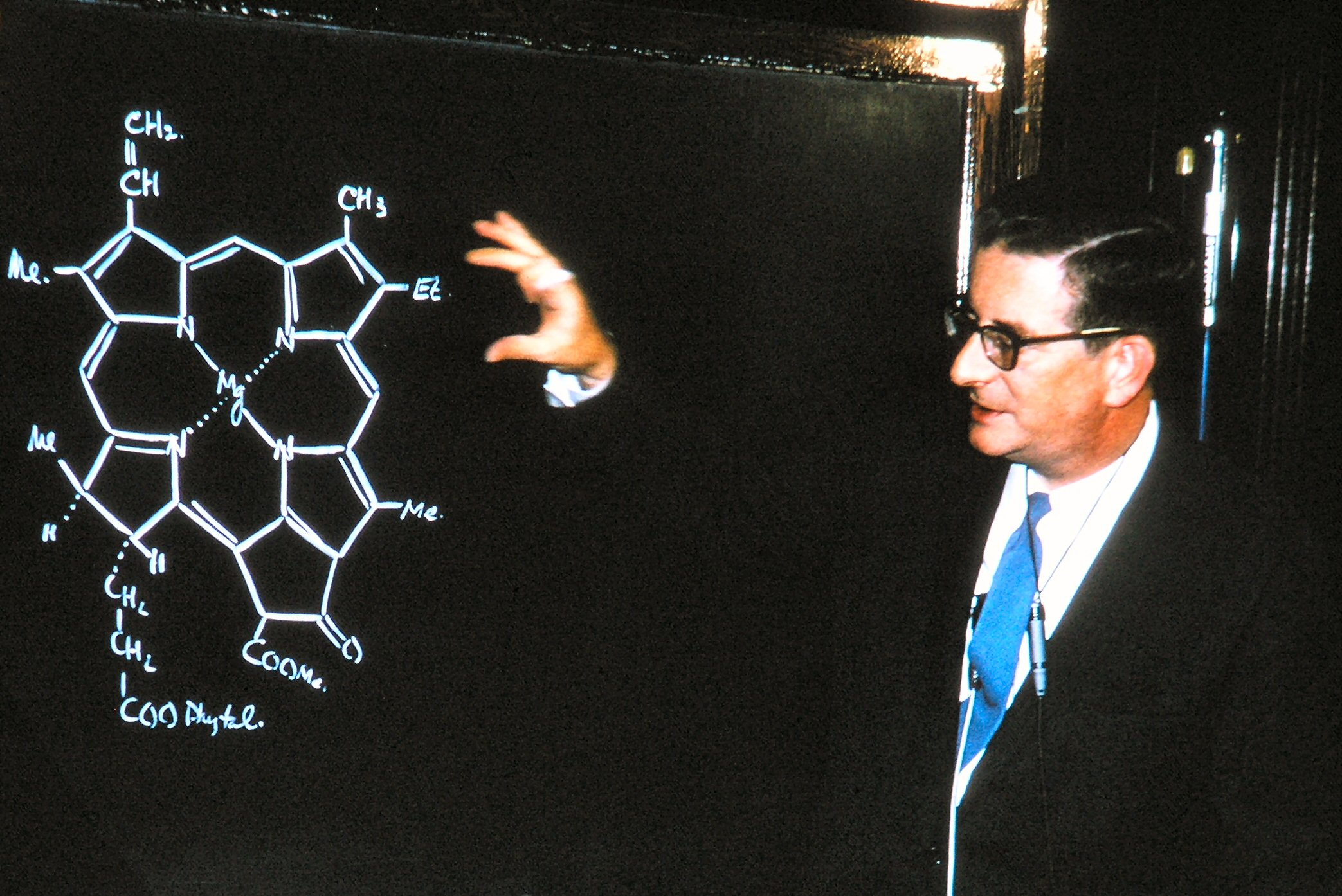

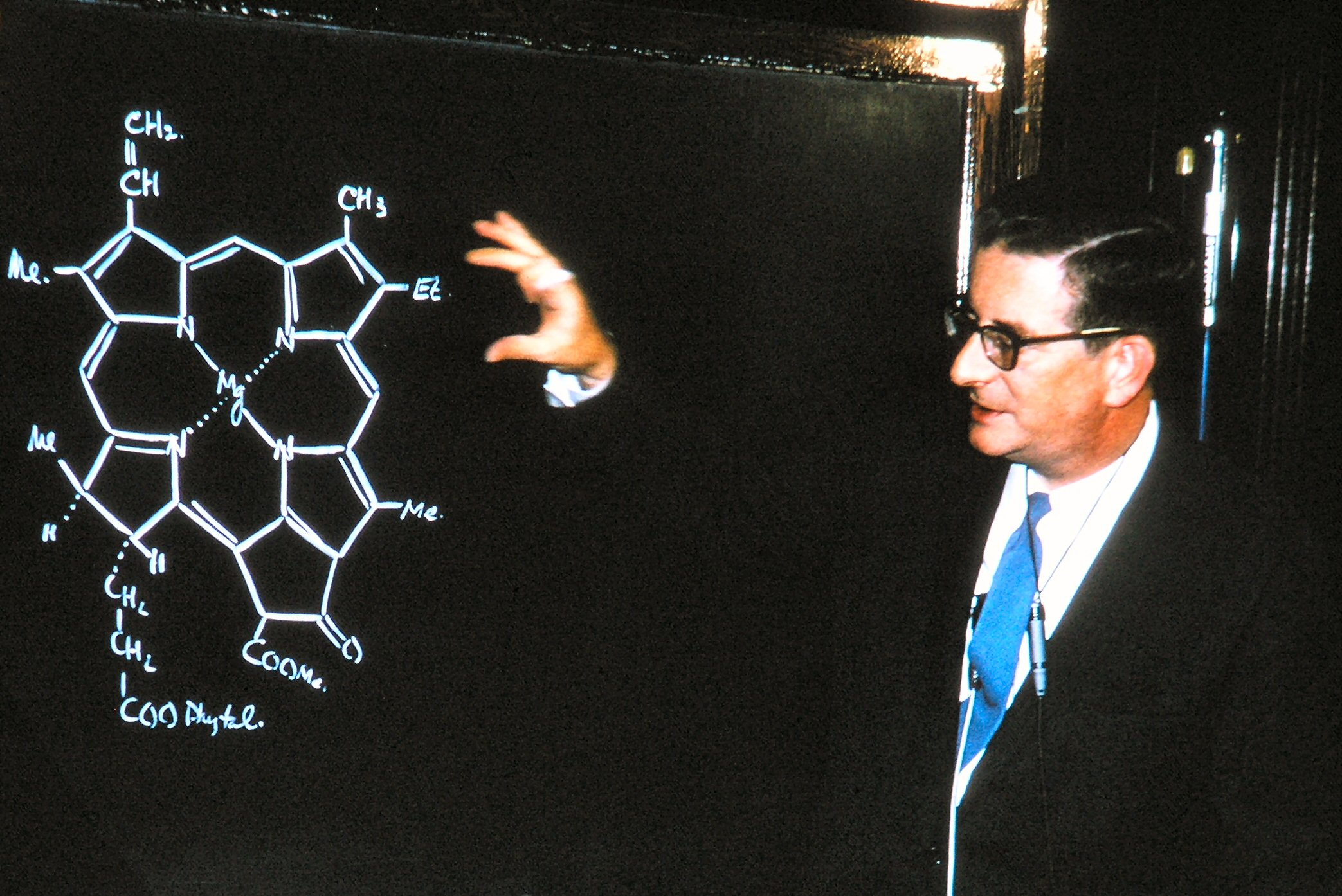

His longest known lecture defined the unit of time known as the "Woodward", after which his other lectures were deemed to be so many "milli-Woodwards" long. In many of these, he eschewed the use of slides and drew structures by using multicolored chalk. Typically, to begin a lecture, Woodward would arrive and lay out two large white handkerchiefs on the countertop. Upon one would be four or five colors of chalk (new pieces), neatly sorted by color, in a long row. Upon the other handkerchief would be placed an equally impressive row of cigarettes. The previous cigarette would be used to light the next one. His Thursday seminars at Harvard often lasted well into the night. He had a fixation with blue, and many of his suits, his car, and even his parking space were coloured in blue. In one of his laboratories, his students hung a large black and white photograph of the master from the ceiling, complete with a large blue "tie" appended. There it hung for some years (early 1970s), until scorched in a minor laboratory fire. He detested exercise, could get along with only a few hours of sleep every night, was a heavy smoker, and enjoyed Scotch whisky and martinis.Robert Burns Woodward

.

Video podcast of Robert Burns Woodward talking about cephalosporinRobert Burns Woodward: Three Score Years and Then?

Robert Burns Woodward Patents

Notes from Robert Burns Woodward's Seminars

taken by Robert E. Kohler i

Science History Institute Digital Collections

* including the Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1965 ''Recent Advances in the Chemistry of Natural Products'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Woodward, Robert Burns 1917 births 1979 deaths 20th-century American chemists 20th-century American educators American Nobel laureates American science writers Foreign Members of the Royal Society Harvard University faculty Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni Wesleyan University people Nobel laureates in Chemistry National Medal of Science laureates Organic chemists Stereochemists People from Belmont, Massachusetts Recipients of the Copley Medal 20th-century American writers Time Person of the Year Members of the American Philosophical Society

organic chemist

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, J. ...

. He is considered by many to be the most preeminent synthetic organic chemist of the twentieth century, having made many key contributions to the subject, especially in the synthesis of complex natural products and the determination of their molecular structure. He also worked closely with Roald Hoffmann

Roald Hoffmann (born Roald Safran; July 18, 1937) is a Polish-American theoretical chemist who won the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He has also published plays and poetry. He is the Frank H. T. Rhodes Professor of Humane Letters, Emeritus, at ...

on theoretical studies of chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the positions of electrons in the forming and breaking ...

s. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

in 1965.

Early life and education

Woodward was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on April 10, 1917. He was the son of Margaret Burns (an immigrant from Scotland who claimed to be a descendant of the poet,Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

) and her husband, Arthur Chester Woodward, himself the son of Roxbury Roxbury may refer to:

Places

;Canada

* Roxbury, Nova Scotia

* Roxbury, Prince Edward Island

;United States

* Roxbury, Connecticut

* Roxbury, Kansas

* Roxbury, Maine

* Roxbury, Boston, a municipality that was later integrated into the city of Bo ...

apothecary, Harlow Elliot Woodward.

His father was one of the many victims of the 1918 influenza pandemic

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

of 1918.

From a very early age, Woodward was attracted to and engaged in private study of chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

while he attended a public primary school, and then Quincy High School, in Quincy, Massachusetts

Quincy ( ) is a coastal U.S. city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county and a part of Metropolitan Boston as one of Boston's immediate southern suburbs. Its population in 2020 was 101,636, making ...

. By the time he entered high school, he had already managed to perform most of the experiments in Ludwig Gattermann's then widely used textbook of experimental organic chemistry. In 1928, Woodward contacted the Consul-General of the German consulate in Boston (Baron von Tippelskirch ), and through him, managed to obtain copies of a few original papers published in German journals. Later, in his Cope lecture, he recalled how he had been fascinated when, among these papers, he chanced upon Diels and Alder's original communication about the Diels–Alder reaction

In organic chemistry, the Diels–Alder reaction is a chemical reaction between a conjugated diene and a substituted alkene, commonly termed the dienophile, to form a substituted cyclohexene derivative. It is the prototypical example of a peric ...

. Throughout his career, Woodward was to repeatedly and powerfully use and investigate this reaction, both in theoretical and experimental ways. In 1933, he entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

(MIT), but neglected his formal studies badly enough to be excluded at the end of the 1934 fall term. MIT readmitted him in the 1935 fall term, and by 1936 he had received the Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

degree. Only one year later, MIT awarded him the doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

, when his classmates were still graduating with their bachelor's degrees.The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1965 - Robert B. Woodward BiographyNobelprize.org Woodward's doctoral work involved investigations related to the synthesis of the female sex hormone

estrone

Estrone (E1), also spelled oestrone, is a steroid, a weak estrogen, and a minor female sex hormone. It is one of three major endogenous estrogens, the others being estradiol and estriol. Estrone, as well as the other estrogens, are synthesized ...

. MIT required that graduate students have research advisors. Woodward's advisors were James Flack Norris

James Flack Norris (January 20, 1871 – August 4, 1940) was an American chemist. Born in Baltimore, Maryland, to a Methodist minister, Norris was educated in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., before studying at Johns Hopkins University, where he gr ...

and Avery Adrian Morton, although it is not clear whether he actually took any of their advice. After a short postdoctoral stint at the University of Illinois, he took a Junior Fellowship at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

from 1937 to 1938, and remained at Harvard in various capacities for the rest of his life. In the 1960s, Woodward was named Donner Professor of Science, a title that freed him from teaching formal courses so that he could devote his entire time to research.

Research and career

Early work

The first major contribution of Woodward's career in the early 1940s was a series of papers describing the application ofultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter ...

in the elucidation of the structure of natural products. Woodward collected together a large amount of empirical data, and then devised a series of rules later called the Woodward's rules, which could be applied to finding out the structures of new natural substances, as well as non-natural synthesized molecules. The expedient use of newly developed instrumental techniques was a characteristic Woodward exemplified throughout his career, and it marked a radical change from the extremely tedious and long chemical methods of structural elucidation that had been used until then.

In 1944, with his post doctoral researcher, William von Eggers Doering

William von Eggers Doering (June 22, 1917 – January 3, 2011) was the Mallinckrodt Professor of Chemistry at Harvard University. Before Harvard, he taught at Columbia (1942–1952) and Yale (1952–1968).

Doering was born in Fort Worth, Tex ...

, Woodward reported the synthesis of the alkaloid

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of simila ...

quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

, used to treat malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

. Although the synthesis was publicized as a breakthrough in procuring the hard to get medicinal compound from Japanese occupied southeast Asia, in reality it was too long and tedious to adopt on a practical scale. Nevertheless, it was a landmark for chemical synthesis. Woodward's particular insight in this synthesis was to realise that the German chemist Paul Rabe had converted a precursor of quinine called quinotoxine to quinine in 1905. Hence, a synthesis of quinotoxine (which Woodward actually synthesized) would establish a route to synthesizing quinine. When Woodward accomplished this feat, organic synthesis was still largely a matter of trial and error, and nobody thought that such complex structures could actually be constructed. Woodward showed that organic synthesis could be made into a rational science, and that synthesis could be aided by well-established principles of reactivity and structure. This synthesis was the first one in a series of exceedingly complicated and elegant syntheses that he would undertake.

Later work and its impact

Culminating in the 1930s, the British chemists Christopher Ingold and Robert Robinson among others had investigated the mechanisms of organic reactions, and had come up with empirical rules which could predict reactivity of organic molecules. Woodward was perhaps the first synthetic organic chemist who used these ideas as a predictive framework in synthesis. Woodward's style was the inspiration for the work of hundreds of successive synthetic chemists who synthesized medicinally important and structurally complex natural products.

Culminating in the 1930s, the British chemists Christopher Ingold and Robert Robinson among others had investigated the mechanisms of organic reactions, and had come up with empirical rules which could predict reactivity of organic molecules. Woodward was perhaps the first synthetic organic chemist who used these ideas as a predictive framework in synthesis. Woodward's style was the inspiration for the work of hundreds of successive synthetic chemists who synthesized medicinally important and structurally complex natural products.

Organic syntheses and Nobel Prize

During the late 1940s, Woodward synthesized many complex natural products includingquinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

, cholesterol

Cholesterol is any of a class of certain organic molecules called lipids. It is a sterol (or modified steroid), a type of lipid. Cholesterol is biosynthesized by all animal cells and is an essential structural component of animal cell memb ...

, cortisone

Cortisone is a pregnene (21-carbon) steroid hormone. It is a naturally-occurring corticosteroid metabolite that is also used as a pharmaceutical prodrug; it is not synthesized in the adrenal glands. Cortisol is converted by the action of the enz ...

, strychnine

Strychnine (, , US chiefly ) is a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the e ...

, lysergic acid, reserpine

Reserpine is a drug that is used for the treatment of high blood pressure, usually in combination with a thiazide diuretic or vasodilator. Large clinical trials have shown that combined treatment with reserpine plus a thiazide diuretic reduces ...

, chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to ...

, cephalosporin

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus ''Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibiotics ...

, and colchicine

Colchicine is a medication used to treat gout and Behçet's disease. In gout, it is less preferred to NSAIDs or steroids. Other uses for colchicine include the management of pericarditis and familial Mediterranean fever. Colchicine is taken b ...

. With these, Woodward opened up a new era of synthesis, sometimes called the 'Woodwardian era' in which he showed that natural products could be synthesized by careful applications of the principles of physical organic chemistry, and by meticulous planning.

Many of Woodward's syntheses were described as spectacular by his colleagues and before he did them, it was thought by some that it would be impossible to create these substances in the lab. Woodward's syntheses were also described as having an element of art in them, and since then, synthetic chemists have always looked for elegance as well as utility in synthesis. His work also involved the exhaustive use of the then newly developed techniques of infrared spectroscopy

Infrared spectroscopy (IR spectroscopy or vibrational spectroscopy) is the measurement of the interaction of infrared radiation with matter by absorption, emission, or reflection. It is used to study and identify chemical substances or functi ...

and later, nuclear magnetic resonance

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a physical phenomenon in which nuclei in a strong constant magnetic field are perturbed by a weak oscillating magnetic field (in the near field) and respond by producing an electromagnetic signal with a ...

spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter ...

. Another important feature of Woodward's syntheses was their attention to stereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereoi ...

or the particular configuration of molecules in three-dimensional space. Most natural products of medicinal importance are effective, for example as drugs, only when they possess a specific stereochemistry. This creates the demand for 'stereoselective synthesis

Enantioselective synthesis, also called asymmetric synthesis, is a form of chemical synthesis. It is defined by IUPAC as "a chemical reaction (or reaction sequence) in which one or more new elements of chirality are formed in a substrate molecu ...

', producing a compound with a defined stereochemistry. While today a typical synthetic route routinely involves such a procedure, Woodward was a pioneer in showing how, with exhaustive and rational planning, one could conduct reactions that were stereoselective. Many of his syntheses involved forcing a molecule into a certain configuration by installing rigid structural elements in it, another tactic that has become standard today. In this regard, especially his syntheses of reserpine

Reserpine is a drug that is used for the treatment of high blood pressure, usually in combination with a thiazide diuretic or vasodilator. Large clinical trials have shown that combined treatment with reserpine plus a thiazide diuretic reduces ...

and strychnine

Strychnine (, , US chiefly ) is a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the e ...

were landmarks.

During World War II, Woodward was an advisor to the War Production Board

The War Production Board (WPB) was an agency of the United States government that supervised war production during World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established it in January 1942, with Executive Order 9024. The WPB replaced the Su ...

on the penicillin project. Although often given credit for proposing the beta-lactam

A lactam is a cyclic amide, formally derived from an amino alkanoic acid. The term is a portmanteau of the words '' lactone'' + ''amide''.

Nomenclature

Greek prefixes in alphabetical order indicate ring size:

* α-Lactam (3-atom rings)

* β-Lac ...

structure of penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from '' Penicillium'' moulds, principally '' P. chrysogenum'' and '' P. rubens''. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum usin ...

, it was actually first proposed by chemists at Merck and Edward Abraham

Sir Edward Penley Abraham, (10 June 1913 – 8 May 1999) was an English biochemist instrumental in the development of the first antibiotics penicillin and cephalosporin.

Early life and education

Abraham was born on 10 June 1913 at 47 South ...

at Oxford and then investigated by other groups, as well (e.g., Shell). Woodward at first endorsed an incorrect tricyclic (thiazolidine

Thiazolidine is a heterocyclic organic compound with the formula (CH2)3(NH)S. It is a 5-membered saturated ring with a thioether group and an amine group in the 1 and 3 positions. It is a sulfur analog of oxazolidine. Thiazolidine is a colorle ...

fused, amino bridged oxazinone) structure put forth by the penicillin group at Peoria. Subsequently, he put his imprimatur

An ''imprimatur'' (sometimes abbreviated as ''impr.'', from Latin, "let it be printed") is a declaration authorizing publication of a book. The term is also applied loosely to any mark of approval or endorsement. The imprimatur rule in the R ...

on the beta-lactam

A lactam is a cyclic amide, formally derived from an amino alkanoic acid. The term is a portmanteau of the words '' lactone'' + ''amide''.

Nomenclature

Greek prefixes in alphabetical order indicate ring size:

* α-Lactam (3-atom rings)

* β-Lac ...

structure, all of this in opposition to the thiazolidine

Thiazolidine is a heterocyclic organic compound with the formula (CH2)3(NH)S. It is a 5-membered saturated ring with a thioether group and an amine group in the 1 and 3 positions. It is a sulfur analog of oxazolidine. Thiazolidine is a colorle ...

– oxazolone structure proposed by Robert Robinson, the then leading organic chemist of his generation. Ultimately, the beta-lactam structure was shown to be correct by Dorothy Hodgkin

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin (née Crowfoot; 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994) was a Nobel Prize-winning British chemist who advanced the technique of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of biomolecules, which became essential fo ...

using X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

in 1945.

Woodward also applied the technique of infrared spectroscopy

Infrared spectroscopy (IR spectroscopy or vibrational spectroscopy) is the measurement of the interaction of infrared radiation with matter by absorption, emission, or reflection. It is used to study and identify chemical substances or functi ...

and chemical degradation to determine the structures of complicated molecules. Notable among these structure determinations were santonic acid, strychnine

Strychnine (, , US chiefly ) is a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the e ...

, magnamycin and terramycin

Oxytetracycline is a broad-spectrum tetracycline antibiotic, the second of the group to be discovered.

Oxytetracycline works by interfering with the ability of bacteria to produce essential proteins. Without these proteins, the bacteria cannot ...

. In each one of these cases, Woodward again showed how rational facts and chemical principles, combined with chemical intuition, could be used to achieve the task.

In the early 1950s, Woodward, along with the British chemist Geoffrey Wilkinson

Sir Geoffrey Wilkinson FRS (14 July 1921 – 26 September 1996) was a Nobel laureate English chemist who pioneered inorganic chemistry and homogeneous transition metal catalysis.

Education and early life

Wilkinson was born at Springside, Todm ...

, then at Harvard, postulated a novel structure for ferrocene

Ferrocene is an organometallic compound with the formula . The molecule is a complex consisting of two cyclopentadienyl rings bound to a central iron atom. It is an orange solid with a camphor-like odor, that sublimes above room temperature, ...

, a compound consisting of a combination of an organic molecule with iron. This marked the beginning of the field of transition metal

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. They are the elements that can ...

organometallic chemistry

Organometallic chemistry is the study of organometallic compounds, chemical compounds containing at least one chemical bond between a carbon atom of an organic molecule and a metal, including alkali, alkaline earth, and transition metals, and s ...

which grew into an industrially very significant field. Wilkinson won the Nobel Prize for this work in 1973, along with Ernst Otto Fischer. Some historians think that Woodward should have shared this prize along with Wilkinson. Remarkably, Woodward himself thought so, and voiced his thoughts in a letter sent to the Nobel Committee.

Woodward won the Nobel Prize in 1965 for his synthesis of complex organic molecules. He had been nominated a total of 111 times from 1946 to 1965. In his Nobel lecture, he described the total synthesis of the antibiotic cephalosporin

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus ''Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibiotics ...

, and claimed that he had pushed the synthesis schedule so that it would be completed around the time of the Nobel ceremony.

B12 synthesis and Woodward–Hoffmann rules

In the early 1960s, Woodward began work on what was the most complex natural product synthesized to date— vitamin B12. In a remarkable collaboration with his colleague Albert Eschenmoser in Zurich, a team of almost one hundred students and postdoctoral workers worked for many years on the synthesis of this molecule. The work was finally published in 1973, and it marked a landmark in the history of organic chemistry. The synthesis included almost a hundred steps, and involved the characteristic rigorous planning and analyses that had always characterised Woodward's work. This work, more than any other, convinced organic chemists that the synthesis of any complex substance was possible, given enough time and planning (see alsopalytoxin

Palytoxin, PTX or PLTX is an intense vasoconstrictor, and is considered to be one of the most poisonous non- protein substances known, second only to maitotoxin in terms of toxicity in mice.

Palytoxin is a polyhydroxylated and partially unsatur ...

, synthesized by the research group of Yoshito Kishi

is a Japanese chemist who is the Morris Loeb Professor of Chemistry at Harvard University. He is known for his contributions to the sciences of organic synthesis and total synthesis.

Kishi was born in Nagoya, Japan and attended Nagoya Univers ...

, one of Woodward's postdoctoral students). As of 2019, no other total synthesis of Vitamin B12 has been published.

That same year, based on observations that Woodward had made during the B12 synthesis, he and Roald Hoffmann

Roald Hoffmann (born Roald Safran; July 18, 1937) is a Polish-American theoretical chemist who won the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He has also published plays and poetry. He is the Frank H. T. Rhodes Professor of Humane Letters, Emeritus, at ...

devised rules (now called the Woodward–Hoffmann rules) for elucidating the stereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereoi ...

of the products of organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

reactions

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure:

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

* Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

*Chain reaction (disambiguation).

Biology and m ...

. Woodward formulated his ideas (which were based on the symmetry

Symmetry (from grc, συμμετρία "agreement in dimensions, due proportion, arrangement") in everyday language refers to a sense of harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance. In mathematics, "symmetry" has a more precise definiti ...

properties of molecular orbital

In chemistry, a molecular orbital is a mathematical function describing the location and wave-like behavior of an electron in a molecule. This function can be used to calculate chemical and physical properties such as the probability of find ...

s) based on his experiences as a synthetic organic chemist; he asked Hoffman to perform theoretical calculations to verify these ideas, which were done using Hoffmann's Extended Hückel method. The predictions of these rules, called the " Woodward–Hoffmann rules" were verified by many experiments. Hoffmann shared the 1981 Nobel Prize for this work along with Kenichi Fukui, a Japanese chemist who had done similar work using a different approach; Woodward had died in 1979 and Nobel Prizes are not awarded posthumously.

Woodward Institute

While at Harvard, Woodward took on the directorship of the Woodward Research Institute, based atBasel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (B ...

, Switzerland, in 1963. He also became a trustee of his alma mater, MIT, from 1966 to 1971, and of the Weizmann Institute of Science

The Weizmann Institute of Science ( he, מכון ויצמן למדע ''Machon Vaitzman LeMada'') is a public research university in Rehovot, Israel, established in 1934, 14 years before the State of Israel. It differs from other Israeli unive ...

in Israel.

Woodward died in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, from a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

in his sleep. At the time, he was working on the synthesis of an antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention ...

, erythromycin

Erythromycin is an antibiotic used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. This includes respiratory tract infections, skin infections, chlamydia infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, and syphilis. It may also be used durin ...

. A student of his said about him:

:''I owe a lot to R. B. Woodward. He showed me that one could attack difficult problems without a clear idea of their outcome, but with confidence that intelligence and effort would solve them. He showed me the beauty of modern organic chemistry, and the relevance to the field of detailed careful reasoning. He showed me that one does not need to specialize. Woodward made great contributions to the strategy of synthesis, to the deduction of difficult structures, to the invention of new chemistry, and to theoretical aspects as well. He taught his students by example the satisfaction that comes from total immersion in our science. I treasure the memory of my association with this remarkable chemist.''

Publications

During his lifetime Woodward authored or coauthored almost 200 publications, of which 85 are full papers, the remainder comprising preliminary communications, the text of lectures, and reviews. The pace of his scientific activity soon outstripped his capacity to publish all experimental details, and much of the work in which he participated was not published until a few years after his death. Woodward trained more than two hundred Ph.D. students and postdoctoral workers, many of whom later went on to distinguished careers. Some of his best-known students includRobert M. Williams

(Colorado State), Harry Wasserman (Yale),

Yoshito Kishi

is a Japanese chemist who is the Morris Loeb Professor of Chemistry at Harvard University. He is known for his contributions to the sciences of organic synthesis and total synthesis.

Kishi was born in Nagoya, Japan and attended Nagoya Univers ...

(Harvard), Stuart Schreiber (Harvard), William R. Roush

William R. Roush is an American organic chemist. He was born on February 20, 1952 in Chula Vista, California. Roush studied chemistry at the University of California Los Angeles (B.S. 1974) and Harvard University (Ph.D. 1977 under Robert Burns Wo ...

( Scripps-Florida), Steven A. Benner

Steven Albert Benner (born October 23, 1954) has been a professor at Harvard University, ETH Zurich, and the University of Florida where he was the V.T. & Louise Jackson Distinguished Professor of Chemistry. In 2005, he founded The Westheimer In ...

(UF), James D. Wuest

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguati ...

(Montreal), Christopher S. Foote (UCLA), Kendall Houk (UCLA), porphyrin chemist Kevin M. Smith (LSU), Thomas R. Hoye (University of Minnesota), Ronald Breslow

Ronald Charles David Breslow (March 14, 1931 – October 25, 2017) was an American chemist from Rahway, New Jersey. He was University Professor at Columbia University, where he was based in the Department of Chemistry and affiliated with the De ...

(Columbia University) and David Dolphin

David H. Dolphin, (born January 15, 1940) is a Canadian biochemist.

He is an internationally recognized expert in porphyrin chemistry and biochemistry. He was the lead creator of Visudyne, a medication used in conjunction with laser treatment ...

(UBC).

Woodward had an encyclopaedic knowledge of chemistry, and an extraordinary memory for detail. Probably the quality that most set him apart from his peers was his remarkable ability to tie together disparate threads of knowledge from the chemical literature and bring them to bear on a chemical problem.

Honors and awards

For his work, Woodward received many awards, honors and honorary doctorates, including election to theAmerican Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1948, the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

in 1953, the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1962, and membership in academies around the world. He was also a consultant to many companies such as Polaroid, Pfizer

Pfizer Inc. ( ) is an American multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology corporation headquartered on 42nd Street in Manhattan, New York City. The company was established in 1849 in New York by two German entrepreneurs, Charles Pfize ...

, and Merck. Other awards include:

* John Scott Medal

John Scott Award, created in 1816 as the John Scott Legacy Medal and Premium, is presented to men and women whose inventions improved the "comfort, welfare, and happiness of human kind" in a significant way. "...the John Scott Medal Fund, establish ...

, from the Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memori ...

and City of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, 1945

* Leo Hendrik Baekeland Award, from the North Jersey Section of the American Chemical Society

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 155,000 members at all ...

, 1955

* Elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1956

* Davy Medal

The Davy Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of London "for an outstandingly important recent discovery in any branch of chemistry". Named after Humphry Davy, the medal is awarded with a monetary gift, initially of £1000 (currently £2000).

H ...

, from the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1959

* Roger Adams Medal, from the American Chemical Society in 1961

* Pius XI Gold Medal, from the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1969

* National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

from the United States in 1964 ("''For an imaginative new approach to the synthesis of complex organic molecules and, especially, for his brilliant syntheses of strychnine, reserphine, lysergic acid, and chlorophyll.''")

* Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

in 1965

* Willard Gibbs Award

The Willard Gibbs Award, presented by thChicago Sectionof the American Chemical Society, was established in 1910 by William A. Converse (1862–1940), a former Chairman and Secretary of the Chicago Section of the society and named for Professor Jo ...

from the Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

Section of the American Chemical Society in 1967

* Lavoisier Medal A Lavoisier Medal is an award named and given in honor of Antoine Lavoisier, considered by some to be a father of modern chemistry.

from the Société chimique de France

Lactalis is a French multinational dairy products corporation, owned by the Besnier family and based in Laval, Mayenne, France. The company's former name was Besnier SA.

Lactalis is the largest dairy products group in the world, and is the s ...

in 1968

* The Order of the Rising Sun

The is a Japanese order, established in 1875 by Emperor Meiji. The Order was the first national decoration awarded by the Japanese government, created on 10 April 1875 by decree of the Council of State. The badge features rays of sunlight f ...

, Second Class from the Emperor of Japan in 1970

* Hanbury Memorial Medal from The Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain in 1970

* Pierre Bruylants Medal from the University of Louvain

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the ...

in 1970

* AMA Scientific Achievement Award in 1971

* Cope Award from the American Chemical Society, shared with Roald Hoffmann

Roald Hoffmann (born Roald Safran; July 18, 1937) is a Polish-American theoretical chemist who won the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He has also published plays and poetry. He is the Frank H. T. Rhodes Professor of Humane Letters, Emeritus, at ...

in 1973

* Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

from the Royal Society, London in 1978

Honorary degrees

Woodward also received over twentyhonorary degrees

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

, including honorary doctorates from the following universities:

* Wesleyan University

Wesleyan University ( ) is a private liberal arts university in Middletown, Connecticut. Founded in 1831 as a men's college under the auspices of the Methodist Episcopal Church and with the support of prominent residents of Middletown, the col ...

in 1945;

* Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

in 1957;

* University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in 1964;

* Brandeis University

, mottoeng = "Truth even unto its innermost parts"

, established =

, type = Private research university

, accreditation = NECHE

, president = Ronald D. Liebowitz

, p ...

in 1965;

* Technion Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

in 1966;

* University of Western Ontario

The University of Western Ontario (UWO), also known as Western University or Western, is a public research university in London, Ontario, Canada. The main campus is located on of land, surrounded by residential neighbourhoods and the Thames R ...

in Canada in 1968;

* University of Louvain

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the ...

in Belgium, 1970.

Personal life

Family

In 1938 he married Irja Pullman; they had two daughters: Siiri Anna (b. 1939) and Jean Kirsten (b. 1944). In 1946, he married Eudoxia Muller, an artist and technician whom he met at the Polaroid Corp. This marriage, which lasted until 1972, produced a daughter, and a son: Crystal Elisabeth (b. 1947), and Eric Richard Arthur (b. 1953).Idiosyncrasies

His lectures frequently lasted for three or four hours.''Remembering organic chemistry legend Robert Burns Woodward Famed chemist would have been 100 this year'' By Bethany Halford C&EN Volume 95 Issue 15 , pp. 28-34 Issue Date: April 10, 201link

His longest known lecture defined the unit of time known as the "Woodward", after which his other lectures were deemed to be so many "milli-Woodwards" long. In many of these, he eschewed the use of slides and drew structures by using multicolored chalk. Typically, to begin a lecture, Woodward would arrive and lay out two large white handkerchiefs on the countertop. Upon one would be four or five colors of chalk (new pieces), neatly sorted by color, in a long row. Upon the other handkerchief would be placed an equally impressive row of cigarettes. The previous cigarette would be used to light the next one. His Thursday seminars at Harvard often lasted well into the night. He had a fixation with blue, and many of his suits, his car, and even his parking space were coloured in blue. In one of his laboratories, his students hung a large black and white photograph of the master from the ceiling, complete with a large blue "tie" appended. There it hung for some years (early 1970s), until scorched in a minor laboratory fire. He detested exercise, could get along with only a few hours of sleep every night, was a heavy smoker, and enjoyed Scotch whisky and martinis.

.

References

Bibliography

* Robert Burns Woodward: Architect and Artist in the World of Molecules; Otto Theodor Benfey, Peter J. T. Morris, Chemical Heritage Foundation, April 2001. * Robert Burns Woodward and the Art of Organic Synthesis: To Accompany an Exhibit by the Beckman Center for the History of Chemistry (Publication / Beckman Center for the History of Chemistry); Mary E. Bowden; Chemical Heritage Foundation, March 1992 * * *Video podcast of Robert Burns Woodward talking about cephalosporin

David Dolphin

David H. Dolphin, (born January 15, 1940) is a Canadian biochemist.

He is an internationally recognized expert in porphyrin chemistry and biochemistry. He was the lead creator of Visudyne, a medication used in conjunction with laser treatment ...

, '' Aldrichimica Acta'', 1977, ''10''(1), 3–9.Robert Burns Woodward Patents

External links

Notes from Robert Burns Woodward's Seminars

taken by Robert E. Kohler i

Science History Institute Digital Collections

* including the Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1965 ''Recent Advances in the Chemistry of Natural Products'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Woodward, Robert Burns 1917 births 1979 deaths 20th-century American chemists 20th-century American educators American Nobel laureates American science writers Foreign Members of the Royal Society Harvard University faculty Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni Wesleyan University people Nobel laureates in Chemistry National Medal of Science laureates Organic chemists Stereochemists People from Belmont, Massachusetts Recipients of the Copley Medal 20th-century American writers Time Person of the Year Members of the American Philosophical Society