Richard Simon (priest) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard Simon CO (13 May 1638 – 11 April 1712), was a French

Richard Simon CO (13 May 1638 – 11 April 1712), was a French

Simon published in 1675 a translation of the travels of Girolamo Dandini in

Simon published in 1675 a translation of the travels of Girolamo Dandini in

Google Books

and in favour of the Catholic Church tradition of interpretation. Jean Le Clerc, in his 1685 work ''Sentimens de quelques théologiens de Hollande'', controverted the views of Simon acutely, and claimed that an uninformed reader might take Simon to be any of a Calvinist, Jew or crypto-Spinozan; Bossuet made a point of banning this also, as even more harmful than Simon's book. It was answered in ''Réponse aux Sentimens de quelques théologiens de Hollande'' by Simon (1686). In France, Simon's work became well known and widely circulated, despite Bossuet's hostility and efforts to keep it marginal. Étienne Fourmont was in effect a disciple of Simon, if not acknowledging the fact. Another orientalist influenced by Simon was Nicolas Barat. An important eighteenth century biblical critic in France that did use Simon's work on the Hebrew Bible was

Google Books

''Factum, servant de responce au livre intitulé Abrégé du procéz fait aux Juifs de Mets''

Paris, 1670. * ''Histoire critique du Vieux Testament'', Paris, 1678;

A critical history of the Old Testament

' (1682), available at archive.org.

''Histoire critique du texte du Nouveau Testament''

(Rotterdam 1689) * ''Histoire critique des versions du Nouveau Testament'', ibid., 1690;

R. Simon, ''Critical Enquiries into the Various Editions of the Bible'' (1684)

* ''Histoire critique des principaux commentateurs du Nouveau Testament'', (Rotterdam, chez Reinier Leers, 1693). * ''Nouvelles observations sur le texte et les versions du Nouveau Testament'', Paris, 1695. * ''Le Nouveau Testament de notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ, traduit sur l’ancienne édition, avec des remarques littérales et critiques sur les principales difficultés'', Trévoux, 1702, v. 4.

''Jewish Encyclopedia'' article

{{DEFAULTSORT:Simon, Richard 1638 births 1712 deaths People from Dieppe, Seine-Maritime French Oratory 18th-century French Roman Catholic priests 17th-century French Roman Catholic priests Christian Hebraists Roman Catholic biblical scholars 17th-century French Catholic theologians French biblical scholars French orientalists Translators of the Bible into French Biblical criticism 17th-century French translators

Richard Simon CO (13 May 1638 – 11 April 1712), was a French

Richard Simon CO (13 May 1638 – 11 April 1712), was a French priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

, a member of the Oratorians, who was an influential biblical critic, orientalist and controversialist.

Early years

Simon was born atDieppe

Dieppe (; Norman: ''Dgieppe'') is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to Newh ...

. His early education took place at the Oratorian college there, and a benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

enabled him to study theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

at Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, where he showed an interest in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

and other Oriental languages

A wide variety of languages are spoken throughout Asia, comprising different language families and some unrelated isolates. The major language families include Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Caucasian, Dravidian, Indo-European, Afroasiatic, Tur ...

. He entered the Oratorians as novice in 1662. At the end of his novitiate

The novitiate, also called the noviciate, is the period of training and preparation that a Christian ''novice'' (or ''prospective'') monastic, apostolic, or member of a religious order undergoes prior to taking vows in order to discern whether t ...

he was sent to teach philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some s ...

at the College of Juilly. But he was soon recalled to Paris, and employed in preparing a catalogue of the Oriental books in the library of the Oratory.

Conflicts as Oratorian

Simon was ordained a priest in 1670. He then taught rhetoric at Juilly until 1673, having among his students the noted philosopher, CountHenri de Boulainvilliers

Henri de Boulainvilliers (; 21 October 1658, Saint-Saire, Normandy – 23 January 1722, Paris) was a French nobleman, writer and historian. He was educated at the College of Juilly; he served in the army until 1697.

Primarily remembered as an ea ...

.

Simon was influenced by the ideas of Isaac La Peyrère who came to live with the Oratorians (though taking little of the specifics), and by Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

. Simon's approach earned him the later recognition as a "Father of the higher criticism

Historical criticism, also known as the historical-critical method or higher criticism, is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts in order to understand "the world behind the text". While often discussed in terms of ...

", though this title is also given to German writers of the following century, as well as to Spinoza himself.

Simon aroused ill will when he strayed into a legal battle. François Verjus was a fellow Oratorian and friend who was acting against the Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, found ...

s of Fécamp Abbey

The Abbey of the Holy Trinity at Fécamp, commonly known as Fécamp Abbey (french: Abbaye de la Trinité de Fécamp), is a Benedictine abbey in Fécamp, Seine-Maritime, Upper Normandy, France.

The abbey is known as the first producer of bénédict ...

on behalf of their commendatory abbot, the Prince de Neubourg. Simon composed a strongly worded memorandum, and the monks complained to the Abbé

''Abbé'' (from Latin ''abbas'', in turn from Greek , ''abbas'', from Aramaic ''abba'', a title of honour, literally meaning "the father, my father", emphatic state of ''abh'', "father") is the French word for an abbot. It is the title for low ...

Abel-Louis de Sainte-Marthe, Provost General of the Oratory from 1672. The charge of Jesuitism was also brought against Simon, on the grounds that his friend's brother, Father Antoine Verjus, was a prominent member of the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

.

Suppression of the ''Histoire critique''

At the time of the printing of Simon's ''Histoire critique du Vieux Testament'', the work passed the censorship of theUniversity of Paris

The University of Paris (french: link=no, Université de Paris), metonymically known as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, active from 1150 to 1970, with the exception between 1793 and 1806 under the French Revolution. ...

, and the Chancellor of the Oratory gave his ''imprimatur

An ''imprimatur'' (sometimes abbreviated as ''impr.'', from Latin, "let it be printed") is a declaration authorizing publication of a book. The term is also applied loosely to any mark of approval or endorsement. The imprimatur rule in the R ...

''. Simon hoped, through the influence of the Jesuit priest, François de la Chaise

François de la Chaise (August 25, 1624 – January 20, 1709) was a French Jesuit priest, the father confessor of King Louis XIV of France.

Biography

François de la Chaise was born at the Château of Aix in Aix-la-Fayette, Puy-de-Dôme, Auver ...

, the king's confessor, and Charles de Sainte-Maure, duc de Montausier

Charles de Sainte-Maure, duc de Montausier (6 October 161017 November 1690), was a French soldier and, from 1668 to 1680, the governor of the dauphin, the eldest son and heir of Louis XIV, King of France.

Biography

Charles was born on 6 October ...

, to be allowed to dedicate the work to King Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Ve ...

; but the king was absent in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture ...

.

The freedom with which Simon expressed himself, especially where he declared that Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

could not be the author of much in the writings attributed to him, gained attention. The influence of Jacques-Benigne Bossuet, at that time tutor to the Dauphin of France

Dauphin of France (, also ; french: Dauphin de France ), originally Dauphin of Viennois (''Dauphin de Viennois''), was the title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France from 1350 to 1791, and from 1824 to 1830. The word ''dauphin'' ...

, was invoked; the chancellor, Michael le Tellier, lent his assistance. A decree of the Royal Council was obtained, and, after a series of intrigues, the whole printing, consisting of 1,300 copies, was seized by the police and destroyed.

Later life

The Oratory then expelled Simon (1678). He retired in 1679 to the curacy of Bolleville, Seine-Maritime. He later returned to Dieppe, where much of his library was lost in the naval bombardment of 1694. He died there on 11 April 1712, at the age of seventy-four.Works

Most of what Simon wrote in biblical criticism was not really new, given the work of previous critics such asLouis Cappel

Louis Cappel (15 October 1585 – 18 June 1658) was a French Protestant churchman and scholar. A Huguenot, he was born at St Elier, near Sedan. He studied theology at the Academy of Sedan and the Academy of Saumur, and Arabic at the Universit ...

, Johannes Morinus, and others. The Jesuit tradition of biblical criticism starting with Alfonso Salmeron

Alfonso (Alphonsus) Salmerón (8 September 1515 – 13 February 1585) was a Spanish biblical scholar, a Catholic priest, and one of the first Jesuits.

Biography

He was born in Toledo, Spain on 8 September 1515. He studied literature and philoso ...

had paved the way for his approach.

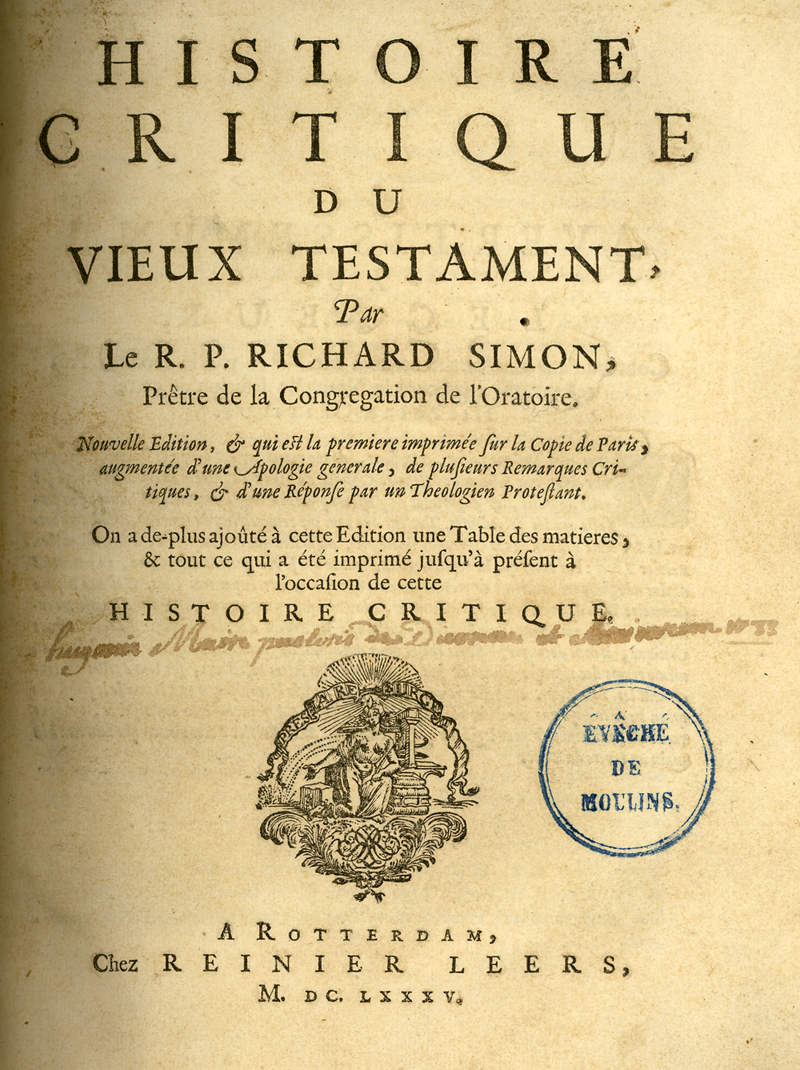

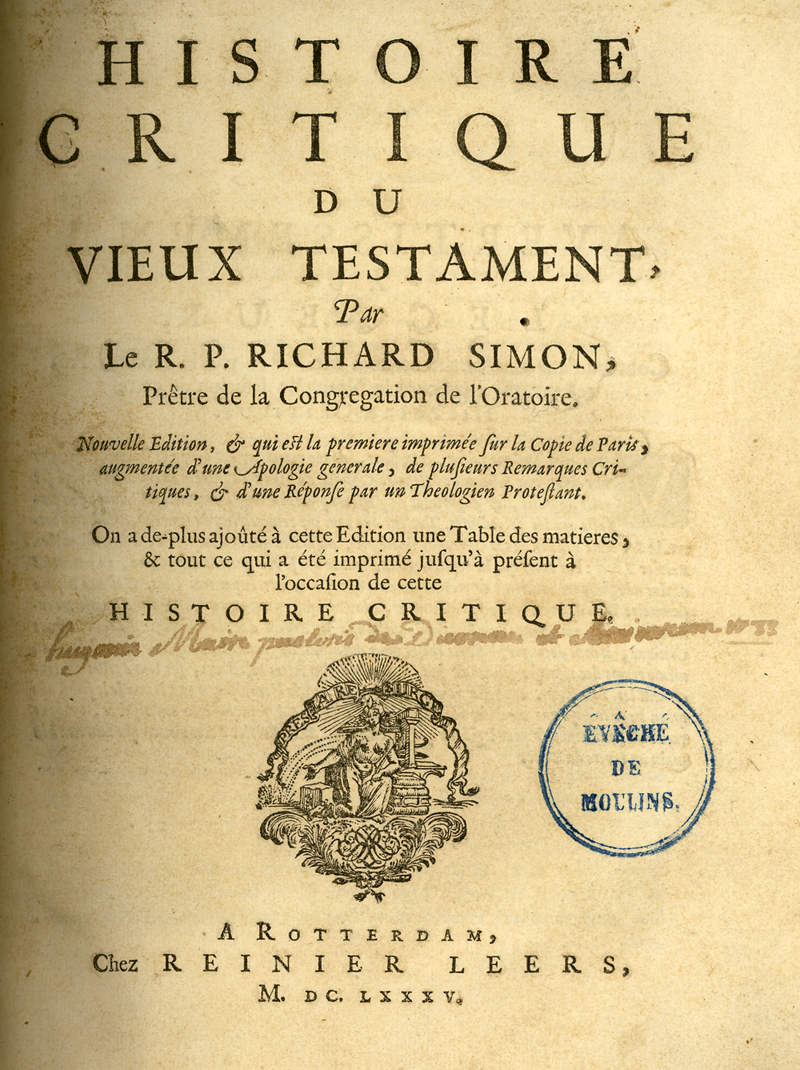

Old Testament

The ''Histoire critique du Vieux Testament'' (1678) consists of three books. The first deals with the text of the Hebrew Bible and the changes which it has undergone, and the authorship of the Mosaic writings and of other books of the Bible. It presents Simon's theory of the existence during early Jewish history of recorders or annalists of the events of each period, whose writings were preserved in the public archives. The second book gives an account of the main translations, ancient and modern, of theOld Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

. The third discusses biblical commentators. The book had a complicated early development. It appeared, with Simon's name on the title page, in the year 1685, from the press of Reinier Leers in Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"Ne ...

. This Dutch edition, in fact the second, superseded the suppressed French first edition, but differed from it in a number of ways. Simon had hoped to overcome the opposition of Bossuet by making changes; these negotiations with Bossuet lasted a considerable time, but finally broke down.

The original French printer of the book, in order to promote sales, had the titles of the chapters printed separately and circulated. These had come into the hands of the Port Royalists, who had undertaken a translation into French of the ''Prolegomena'' to Brian Walton's '' Polyglott''. To counteract this, Simon announced his intention of publishing an annotated edition of the ''Prolegomena'', and added to the ''Histoire critique'' a translation of the last four chapters of that work, not part of his original plan. Simon's announcement prevented the appearance of the projected translation.

A faulty edition of the ''Histoire critique'' had previously been published at Amsterdam by Daniel Elzevir, based on a manuscript transcription of one of the copies of the original work which had been sent to England; and from which a Latin translation (''Historia critica Veteris Testamenti'', 1681, by Noël Aubert de Versé) and an English translation (''Critical History of the Old Testament'', London, 1682) were made. The edition of Leers was a reproduction of the work as first printed, with a new preface, notes, and those other writings which had appeared for and against the work up to that date; it included Simon's answers to criticisms of Charles de Veil and Friedrich Spanheim the Younger.

New Testament

In 1689 appeared Simon's companion ''Histoire critique du texte du Nouveau Testament'', consisting of thirty-three chapters. In it he discusses: the origin and character of the various books, with a consideration of the objections brought against them by the Jews and others; the quotations from the Old Testament in the New; the inspiration of the New Testament (with a refutation of the opinions ofBaruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

); the Greek dialect in which they are written (against Claudius Salmasius

Claude Saumaise (15 April 1588 – 3 September 1653), also known by the Latin name Claudius Salmasius, was a French classical scholar.

Life

Salmasius was born at Semur-en-Auxois in Burgundy. His father, a counsellor of the parlement of Dijon, ...

); and the Greek manuscripts known at the time, especially ''Codex Bezae

The Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, designated by siglum D or 05 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering of New Testament manuscripts), δ 5 (in the von Soden of New Testament manuscript), is a codex of the New Testament dating from the 5th century writt ...

'' (Cantabrigiensis).

There followed in 1690 his ''Histoire critique des versions du Nouveau Testament'', where he gives an account of the various translations, both ancient and modern, and discusses the way in which difficult passages of the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christi ...

have been rendered in the various versions. In 1693 was published the ''Histoire critique des principaux commentateurs du Nouveau Testament depuis le commencement du Christianisme jusques a notre tems''. ''Nouvelles Observations sur le texte et les versions du Nouveau Testament'' (Paris, 1695) contains supplementary observations on the subjects of the text and translations of the New Testament.

In 1702 Simon published at Trévoux

Trévoux (; frp, Trevôrs) is a commune in the Ain department in eastern France. The inhabitants are known as Trévoltiens.

It is a suburb of Lyon, built on the steeply sloping left bank of the river Saône.

History

In AD 843, the treaty of ...

his own translation into French of the New Testament (the ''version de Trévoux''). It was substantially based on the Latin Vulgate

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels us ...

, but was annotated in such a way as to cast doubt on traditional readings that were backed by Church authority. Again Bossuet did what he could to suppress the work. Despite changes over two decades in how Bossuet was able to exert influence through his circle of contacts, he again mobilised against Simon beyond the boundaries of his diocese.

Other works

As a controversialist, Simon tended to use pseudonyms, and to display bitterness. Simon was early at odds with the Port-Royalists.Antoine Arnauld

Antoine Arnauld (6 February 16128 August 1694) was a French Catholic theologian, philosopher and mathematician. He was one of the leading intellectuals of the Jansenist group of Port-Royal and had a very thorough knowledge of patristics. Contem ...

had compiled with others a work ''Perpétuité de la foi'' (On the Perpetuity of the Faith), the first volume of which dealt with the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

. After François Diroys, who knew both of them, had involved Simon in commenting on the work, Simon's criticisms from 1669 aroused indignation in Arnauld's camp.

Simon's first major publication followed, his ''Fides Ecclesiae orientalis, seu Gabrielis Metropolitae Philadelphiensis opuscula, cum interpretatione Latina, cum notis'' (Paris, 1671), on a work of (1541–1616), the object of which was to demonstrate that the belief of the Greek Church regarding the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

was the same as that of the Church of Rome. In 1670 he had written a pamphlet in defence of the Jews of Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand Es ...

, who had been accused of having murdered a Christian child.

Simon published in 1675 a translation of the travels of Girolamo Dandini in

Simon published in 1675 a translation of the travels of Girolamo Dandini in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, as ''Voyage au Mont Liban'' (1675). Dandini was a perceptive observer, and Simon in his preface argued for the utility of travel to theologians.

In 1676 contacts with Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Bez ...

s at Charenton led Simon to circulate a manuscript project for a new version of the Bible. This was a sample for a proposed improved edition of the Giovanni Diodati translation; but after Simon had translated the Pentateuch

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

the funding ran out.

Reception

The ''Histoire critique du Vieux Testament'' encountered strong opposition from Catholics who disliked Simon's diminishing of the authority of theChurch Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical p ...

. Protestants widely felt that an infallible Bible was threatened by doubts which Simon raised against the integrity of the Hebrew text; and indeed Simon as basic tenets argued against ''sola scriptura

, meaning by scripture alone, is a Christian theological doctrine held by most Protestant Christian denominations, in particular the Lutheran and Reformed traditions of Protestantism, that posits the Bible as the sole infallible source of aut ...

''David Lyle Jeffrey, Gregory P. Maillet, ''Christianity and Literature: Philosophical Foundations and Critical Practice'' (2011), p. 221Google Books

and in favour of the Catholic Church tradition of interpretation. Jean Le Clerc, in his 1685 work ''Sentimens de quelques théologiens de Hollande'', controverted the views of Simon acutely, and claimed that an uninformed reader might take Simon to be any of a Calvinist, Jew or crypto-Spinozan; Bossuet made a point of banning this also, as even more harmful than Simon's book. It was answered in ''Réponse aux Sentimens de quelques théologiens de Hollande'' by Simon (1686). In France, Simon's work became well known and widely circulated, despite Bossuet's hostility and efforts to keep it marginal. Étienne Fourmont was in effect a disciple of Simon, if not acknowledging the fact. Another orientalist influenced by Simon was Nicolas Barat. An important eighteenth century biblical critic in France that did use Simon's work on the Hebrew Bible was

Jean Astruc

Jean Astruc (19 March 1684, in Sauve, France – 5 May 1766, in Paris) was a professor of medicine in France at Montpellier and Paris, who wrote the first great treatise on syphilis and venereal diseases, and also, with a small anonymously pu ...

.

The identity of the translator of the 1682 English version ''Critical History of the Old Testament'' is unclear, being often given as a Henry Dickinson who is an obscure figure, and sometimes as John Hampden

John Hampden (24 June 1643) was an English landowner and politician whose opposition to arbitrary taxes imposed by Charles I made him a national figure. An ally of Parliamentarian leader John Pym, and cousin to Oliver Cromwell, he was one of th ...

; John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the p ...

wrote his '' Religio Laici'' in response with a dedication to Dickinson, and Simon's work became well known. Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

took an interest in Simon's New Testament criticism in the early 1690s, pointed out to him by John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

, adding from it to an Arian

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God t ...

summary of his views that was intended for publication by Le Clerc, but remained in manuscript. Later Samuel Clarke

Samuel Clarke (11 October 1675 – 17 May 1729) was an English philosopher and Anglican cleric. He is considered the major British figure in philosophy between John Locke and George Berkeley.

Early life and studies

Clarke was born in Norwich, t ...

published his ''The Divine Authority of the Holy Scriptures Asserted'' (1699) in reply to Simon. Simon's works were later an influence on Johann Salomo Semler

Johann Salomo Semler (18 December 1725 – 14 March 1791) was a German church historian, biblical commentator, and critic of ecclesiastical documents and of the history of dogmas. He is sometimes known as "the father of German rationalism".

Youth ...

.Joel B. Green, ''Hearing the New Testament: strategies for interpretation'' (1995), p. 12Google Books

Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

's 1897 catalogue of condemned books contains several works by Richard Simon.

Bibliography

''Factum, servant de responce au livre intitulé Abrégé du procéz fait aux Juifs de Mets''

Paris, 1670. * ''Histoire critique du Vieux Testament'', Paris, 1678;

A critical history of the Old Testament

' (1682), available at archive.org.

''Histoire critique du texte du Nouveau Testament''

(Rotterdam 1689) * ''Histoire critique des versions du Nouveau Testament'', ibid., 1690;

R. Simon, ''Critical Enquiries into the Various Editions of the Bible'' (1684)

* ''Histoire critique des principaux commentateurs du Nouveau Testament'', (Rotterdam, chez Reinier Leers, 1693). * ''Nouvelles observations sur le texte et les versions du Nouveau Testament'', Paris, 1695. * ''Le Nouveau Testament de notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ, traduit sur l’ancienne édition, avec des remarques littérales et critiques sur les principales difficultés'', Trévoux, 1702, v. 4.

Notes

Attribution *References

* Jonathan I. Israel (2001), ''Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650-1750'', New York: Oxford University Press.Further reading

For the life of Simon: *Life or "éloge" by his grand-nephew De la Martinière in vol. i. of the ''Lettres choisies'' (4 vols., Amsterdam, 1730). *K. H. Graf's article in the first volume of the ''Beiträge zu den theologischen Wissenschaften'', etc. (Jena, 1851). * E. W. E. Reuss's article, revised by E. Nestle, in Herzog-Hauck, ''Realencyklopädie'' (ad. 1906). * ''Richard Simon et son Histoire critique du Vieux Testament'', by Auguste Bernus (Lausanne, 1869). * Henri Margival, ''Essai sur Richard Simon et la critique biblique au XVIIe siècle'' (1900). *Jean-Pierre Thiollet

Jean-Pierre Thiollet (; born 9 December 1956) is a French writer and journalist.

Primarily living in Paris, he is the author of numerous books and one of the national leaders of the European Confederation of Independent Trade Unions (CEDI), a ...

, ''Je m'appelle Byblos'' (Richard Simon, pp. 244–247), Paris, 2005. .

External links

''Jewish Encyclopedia'' article

{{DEFAULTSORT:Simon, Richard 1638 births 1712 deaths People from Dieppe, Seine-Maritime French Oratory 18th-century French Roman Catholic priests 17th-century French Roman Catholic priests Christian Hebraists Roman Catholic biblical scholars 17th-century French Catholic theologians French biblical scholars French orientalists Translators of the Bible into French Biblical criticism 17th-century French translators