Richard Owen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

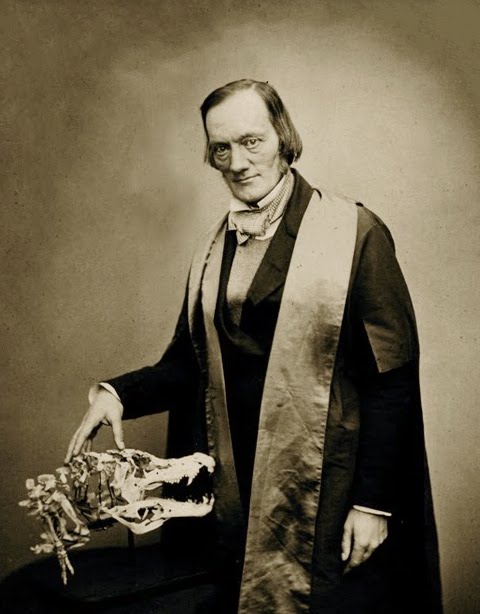

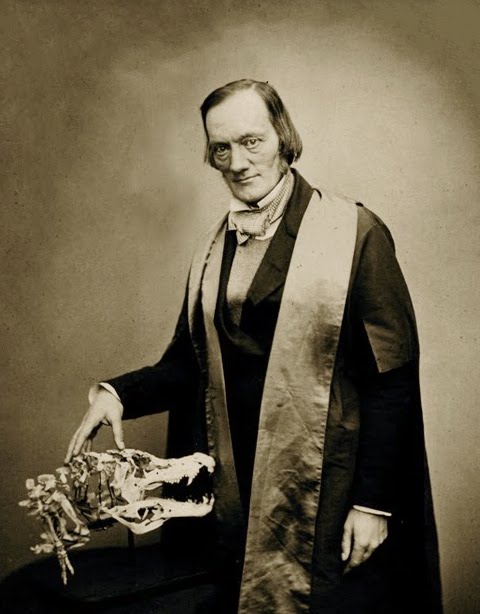

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English

Owen became a surgeon's apprentice in 1820 and was appointed to the

Owen became a surgeon's apprentice in 1820 and was appointed to the  Owen always tended to support orthodox men of science and the ''status quo''. The royal family presented him with the cottage in Richmond Park and Robert Peel put him on the

Owen always tended to support orthodox men of science and the ''status quo''. The royal family presented him with the cottage in Richmond Park and Robert Peel put him on the

While occupied with the cataloguing of the Hunterian collection, Owen did not confine his attention to the preparations before him but also seized every opportunity to dissect fresh subjects. He was allowed to examine all animals that died in London Zoo's gardens and, when the Zoo began to publish scientific proceedings, in 1831, he was the most prolific contributor of anatomical papers. His first notable publication, however, was his ''Memoir on the Pearly

While occupied with the cataloguing of the Hunterian collection, Owen did not confine his attention to the preparations before him but also seized every opportunity to dissect fresh subjects. He was allowed to examine all animals that died in London Zoo's gardens and, when the Zoo began to publish scientific proceedings, in 1831, he was the most prolific contributor of anatomical papers. His first notable publication, however, was his ''Memoir on the Pearly

Most of his work on

Most of his work on

From p. 103:

"The combination of such characters ... will, it is presumed, be deemed sufficient ground for establishing a distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria*. (*Gr. ''δεινός'', fearfully great; ''σαύρος'', a lizard. ... )" Owen used 3 genera to define the dinosaurs: the carnivorous ''

Science historian Evelleen Richards has argued that Owen was likely sympathetic to developmental theories of evolution, but backed away from publicly proclaiming them after the critical reaction that had greeted the anonymously published evolutionary book '' Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' in 1844 (it was revealed only decades later that the book had been authored by publisher Robert Chambers). Owen had been criticised for his own evolutionary remarks in his ''On the Nature of Limbs'' in 1849. At the end of ''On the Nature of Limbs'', Owen suggested that humans ultimately evolved from fish as the result of natural laws, which resulted in Owen being criticized in the ''Manchester Spectator'' for denying that species such as humans were created by God.

Owen, as president-elect of the British Association, announced his authoritative anatomical studies of primate brains, stating that the human brain had structures that ape brains did not and that therefore humans were a separate sub-class, starting a dispute which was subsequently satirised as the Great Hippocampus Question. Owen's main argument was that humans have much larger brains for their body size than other mammals including the great apes.

In 1862 (and later occasions) Thomas Huxley took the opportunity to arrange demonstrations of ape brain anatomy (e.g. at the BA meeting, where William Flower performed the dissection). Visual evidence of the supposedly missing structures ( posterior cornu and hippocampus minor) was used, in effect, to indict Owen for perjury: Owen had argued that the absence of those structures in apes was connected with the lesser size to which the ape brains grew, but he then conceded that a poorly developed version might be construed as present without preventing him from arguing that brain size was still the major way of distinguishing apes and humans.

Science historian Evelleen Richards has argued that Owen was likely sympathetic to developmental theories of evolution, but backed away from publicly proclaiming them after the critical reaction that had greeted the anonymously published evolutionary book '' Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' in 1844 (it was revealed only decades later that the book had been authored by publisher Robert Chambers). Owen had been criticised for his own evolutionary remarks in his ''On the Nature of Limbs'' in 1849. At the end of ''On the Nature of Limbs'', Owen suggested that humans ultimately evolved from fish as the result of natural laws, which resulted in Owen being criticized in the ''Manchester Spectator'' for denying that species such as humans were created by God.

Owen, as president-elect of the British Association, announced his authoritative anatomical studies of primate brains, stating that the human brain had structures that ape brains did not and that therefore humans were a separate sub-class, starting a dispute which was subsequently satirised as the Great Hippocampus Question. Owen's main argument was that humans have much larger brains for their body size than other mammals including the great apes.

In 1862 (and later occasions) Thomas Huxley took the opportunity to arrange demonstrations of ape brain anatomy (e.g. at the BA meeting, where William Flower performed the dissection). Visual evidence of the supposedly missing structures ( posterior cornu and hippocampus minor) was used, in effect, to indict Owen for perjury: Owen had argued that the absence of those structures in apes was connected with the lesser size to which the ape brains grew, but he then conceded that a poorly developed version might be construed as present without preventing him from arguing that brain size was still the major way of distinguishing apes and humans.

Huxley's campaign ran over two years and was devastatingly successful at persuading the overall scientific community, with each "slaying" being followed by a recruiting drive for the Darwinian cause. The spite lingered. While Owen had argued that humans were distinct from apes by virtue of having large brains, Huxley said that racial diversity blurred any such distinction. In his paper criticising Owen, Huxley directly states:

: ... "if we place , the European brain, , the Bosjesman brain, and , the orang brain, in a series, the differences between and , so far as they have been ascertained, are of the same nature as the chief of those between and ".

Owen countered Huxley by saying the brains of all human races were really of similar size and intellectual ability, and that the fact that humans had brains that were twice the size of large apes like male gorillas, even though humans had much smaller bodies, made humans distinguishable.

Huxley's campaign ran over two years and was devastatingly successful at persuading the overall scientific community, with each "slaying" being followed by a recruiting drive for the Darwinian cause. The spite lingered. While Owen had argued that humans were distinct from apes by virtue of having large brains, Huxley said that racial diversity blurred any such distinction. In his paper criticising Owen, Huxley directly states:

: ... "if we place , the European brain, , the Bosjesman brain, and , the orang brain, in a series, the differences between and , so far as they have been ascertained, are of the same nature as the chief of those between and ".

Owen countered Huxley by saying the brains of all human races were really of similar size and intellectual ability, and that the fact that humans had brains that were twice the size of large apes like male gorillas, even though humans had much smaller bodies, made humans distinguishable.

Owen also resorted to the same subterfuge he used against Mantell, writing another anonymous article in the ''

Owen also resorted to the same subterfuge he used against Mantell, writing another anonymous article in the ''

Volume I, Fishes and Reptiles

Volume II, Birds and Mammals

Volume III, Mammals

* ''Memoir of the Dodo'' (1866) Full book on Wiki commons * ''Monograph of the Fossil Mammalia of the Mesozoic Formations'' (1871) * ''Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa'' (1876) * ''Antiquity of Man as deduced from the Discovery of a Human Skeleton during Excavations of the Docks at Tilbury'' (1884)

(accessed 16 December 2010)

biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

, comparative anatomist

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

and palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s.

Owen produced a vast array of scientific work, but is probably best remembered today for coining the word '' Dinosauria'' (meaning "Terrible Reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

" or "Fearfully Great Reptile"). An outspoken critic of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's theory of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

by natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

, Owen agreed with Darwin that evolution occurred but thought it was more complex than outlined in Darwin's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

''. page range too broad''">Wikipedia:Citing sources">page range too broad''/sup> Owen's approach to evolution can be considered to have anticipated the issues that have gained greater attention with the recent emergence of evolutionary developmental biology

Evolutionary developmental biology, informally known as evo-devo, is a field of biological research that compares the developmental biology, developmental processes of different organisms to infer how developmental processes evolution, evolved. ...

.

Owen was the first president of the Microscopical Society of London in 1839 and edited many issues of its journal – then known as '' The Microscopic Journal''. Owen also campaigned for the natural specimens in the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

to be given a new home. This resulted in the establishment, in 1881, of the now world-famous Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

in South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

, London. page range too broad''">Wikipedia:Citing sources">page range too broad''/sup> Bill Bryson

William McGuire Bryson ( ; born 8 December 1951) is an American-British journalist and author. Bryson has written a number of nonfiction books on topics including travel, the English language, and science. Born in the United States, he has be ...

argues that, "by making the Natural History Museum an institution for everyone, Owen transformed our expectations of what museums are for."

While he made several contributions to science and public learning, Owen was a controversial figure among his contemporaries, both for his disagreements on matters of common descent and for accusations that he took credit for other people's work.

Biography

Owen became a surgeon's apprentice in 1820 and was appointed to the

Owen became a surgeon's apprentice in 1820 and was appointed to the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

in 1826. In 1836, Owen was appointed Hunterian professor at the Royal College, and in 1849, he succeeded William Clift as conservator of the Hunterian Museum. He held the latter office until 1856 when he became superintendent of the natural history department of the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

. He then devoted much of his energies to a great scheme for a National Museum of Natural History, which eventually resulted in the removal of the natural history collections of the British Museum to a new building at South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

: the British Museum (Natural History) (now the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

). He retained office until the completion of this work, in December 1883, when he was made a knight of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

.

Owen always tended to support orthodox men of science and the ''status quo''. The royal family presented him with the cottage in Richmond Park and Robert Peel put him on the

Owen always tended to support orthodox men of science and the ''status quo''. The royal family presented him with the cottage in Richmond Park and Robert Peel put him on the Civil List

A civil list is a list of individuals to whom money is paid by the government, typically for service to the state or as honorary pensions. It is a term especially associated with the United Kingdom, and its former colonies and dominions. It was ori ...

. In 1843, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

. In 1844 he became an associated member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands. When this Institute became the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1851, he joined as a foreign member. In 1845, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.

He died at home on 15 December 1892 and is buried in the churchyard at St Andrew's Church, Ham, near Richmond, Surrey.

Work on invertebrates

Nautilus

A nautilus (; ) is any of the various species within the cephalopod family Nautilidae. This is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and the suborder Nautilina.

It comprises nine living species in two genera, the type genus, ty ...

'' (London, 1832), which was soon recognized as a classic. Thenceforth, he continued to make important contributions to every department of comparative anatomy and zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

for a period of over fifty years. In the sponges, Owen was the first to describe the now well-known Venus' Flower Basket or '' Euplectella'' (1841, 1857). Among Entozoa, his most noteworthy discovery was that of ''Trichina spiralis'' (1835), the parasite infesting the muscles of man in the disease now termed trichinosis (see also, however, Sir James Paget). Of Brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum (biology), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear e ...

a he made very special studies, which much advanced knowledge and settled the classification that has long been accepted. Among Mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

a, he described not only the pearly nautilus but also '' Spirula'' (1850) and other Cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

a, both living and extinct, and it was he who proposed the universally-accepted subdivision of this class into the two orders of Dibranchiata and Tetrabranchiata (1832). In 1852 Owen named '' Protichnites'' – the oldest footprints found on land. Applying his knowledge of anatomy, he correctly postulated that these Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

trackways were made by an extinct type of arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

, and he did this more than 150 years before any fossils of the animal were found. Owen envisioned a resemblance of the animal to the living arthropod '' Limulus''.

Fish, reptiles, birds, and naming of dinosaurs

Most of his work on

Most of his work on reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s related to the skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

s of extinct forms and his chief memoirs, on British specimens, were reprinted in a connected series in his ''History of British Fossil Reptiles'' (4 vols. London 1849–1884). He published the first important general account of the great group of Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

land-reptiles, and he coined the name Dinosauria from Greek ''δεινός'' (''deinos'') "terrible, powerful, wondrous" + ''σαύρος'' (''sauros'') "lizard".; see p. 103.From p. 103:

"The combination of such characters ... will, it is presumed, be deemed sufficient ground for establishing a distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria*. (*Gr. ''δεινός'', fearfully great; ''σαύρος'', a lizard. ... )" Owen used 3 genera to define the dinosaurs: the carnivorous ''

Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Ancient Greek, Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic Epoch (Bathonian stage, 166 ...

'', the herbivorous ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species found worldwide have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, Taxonomy (bi ...

'' and armoured '' Hylaeosaurus, specimens uncovered in southern England.

With Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, Owen helped create the first life-sized models of dinosaurs as he thought they might have appeared. Some models were initially created for the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

of 1851 held in London's Hyde Park, but 33 were eventually produced when the Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around ...

was relocated to Crystal Palace Park, in south London. Owen famously hosted a dinner for 21 prominent men of science inside the hollow concrete ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species found worldwide have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, Taxonomy (bi ...

'' on New Year's Eve 1853. However, in 1849, a few years before his death in 1852, Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons, MRCS Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was an English obstetrician, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstr ...

had realised that ''Iguanodon'', of which he was the discoverer, was not a heavy, pachyderm-like animal, as Owen was proposing, but had slender forelimbs.

Work on mammals

Owen was grantedright of first refusal

Right of first refusal (ROFR or RFR) is a contractual right that gives its holder the option to enter a business transaction with the owner of something, according to specified terms, before the owner is entitled to enter into that transactio ...

on any freshly dead animal at the London Zoo. His wife once arrived home to find the carcass of a newly deceased rhinoceros in her front hallway.

At the same time, Sir Thomas Mitchell's discovery of fossil bones, in New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

, provided material for the first of Owen's long series of papers on the extinct mammals of Australia, which were eventually reprinted in book-form in 1877. He described '' Diprotodon'' (1838) and '' Thylacoleo'' (1859), and extinct species kangaroo

Kangaroos are marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use, the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern gre ...

s and wombats of gigantic size. Most fossil material found in Australia and New Zealand was initially sent to England for expert examination, and with the assistance of the local collectors Owen became the first authority on the palaeontology of the region. While occupied with so much material from abroad, Owen was also busily collecting facts for an exhaustive work on similar fossils from the British Isles and, in 1844–1846, he published his ''History of British Fossil Mammals and Birds'', which was followed by many later memoirs, notably his ''Monograph of the Fossil Mammalia of the Mesozoic Formations'' (Palaeont. Soc., 1871). One of his latest publications was a little work entitled ''Antiquity of Man as deduced from the Discovery of a Human Skeleton during Excavations of the Docks at Tilbury'' (London, 1884).

Owen, Darwin, and the theory of evolution

Sometime during the 1840s Owen came to the conclusion that species arise as the result of some sort of evolutionary process. He believed that there were a total of six possible mechanisms:Parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek + ) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which the embryo develops directly from an egg without need for fertilization. In animals, parthenogenesis means the development of an embryo from an unfertiliz ...

, prolonged development, premature birth, congenital malformations, Lamarckian atrophy, Lamarckian hypertrophy and transmutation, of which he thought transmutation was the least likely.

Science historian Evelleen Richards has argued that Owen was likely sympathetic to developmental theories of evolution, but backed away from publicly proclaiming them after the critical reaction that had greeted the anonymously published evolutionary book '' Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' in 1844 (it was revealed only decades later that the book had been authored by publisher Robert Chambers). Owen had been criticised for his own evolutionary remarks in his ''On the Nature of Limbs'' in 1849. At the end of ''On the Nature of Limbs'', Owen suggested that humans ultimately evolved from fish as the result of natural laws, which resulted in Owen being criticized in the ''Manchester Spectator'' for denying that species such as humans were created by God.

Owen, as president-elect of the British Association, announced his authoritative anatomical studies of primate brains, stating that the human brain had structures that ape brains did not and that therefore humans were a separate sub-class, starting a dispute which was subsequently satirised as the Great Hippocampus Question. Owen's main argument was that humans have much larger brains for their body size than other mammals including the great apes.

In 1862 (and later occasions) Thomas Huxley took the opportunity to arrange demonstrations of ape brain anatomy (e.g. at the BA meeting, where William Flower performed the dissection). Visual evidence of the supposedly missing structures ( posterior cornu and hippocampus minor) was used, in effect, to indict Owen for perjury: Owen had argued that the absence of those structures in apes was connected with the lesser size to which the ape brains grew, but he then conceded that a poorly developed version might be construed as present without preventing him from arguing that brain size was still the major way of distinguishing apes and humans.

Science historian Evelleen Richards has argued that Owen was likely sympathetic to developmental theories of evolution, but backed away from publicly proclaiming them after the critical reaction that had greeted the anonymously published evolutionary book '' Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' in 1844 (it was revealed only decades later that the book had been authored by publisher Robert Chambers). Owen had been criticised for his own evolutionary remarks in his ''On the Nature of Limbs'' in 1849. At the end of ''On the Nature of Limbs'', Owen suggested that humans ultimately evolved from fish as the result of natural laws, which resulted in Owen being criticized in the ''Manchester Spectator'' for denying that species such as humans were created by God.

Owen, as president-elect of the British Association, announced his authoritative anatomical studies of primate brains, stating that the human brain had structures that ape brains did not and that therefore humans were a separate sub-class, starting a dispute which was subsequently satirised as the Great Hippocampus Question. Owen's main argument was that humans have much larger brains for their body size than other mammals including the great apes.

In 1862 (and later occasions) Thomas Huxley took the opportunity to arrange demonstrations of ape brain anatomy (e.g. at the BA meeting, where William Flower performed the dissection). Visual evidence of the supposedly missing structures ( posterior cornu and hippocampus minor) was used, in effect, to indict Owen for perjury: Owen had argued that the absence of those structures in apes was connected with the lesser size to which the ape brains grew, but he then conceded that a poorly developed version might be construed as present without preventing him from arguing that brain size was still the major way of distinguishing apes and humans.

Huxley's campaign ran over two years and was devastatingly successful at persuading the overall scientific community, with each "slaying" being followed by a recruiting drive for the Darwinian cause. The spite lingered. While Owen had argued that humans were distinct from apes by virtue of having large brains, Huxley said that racial diversity blurred any such distinction. In his paper criticising Owen, Huxley directly states:

: ... "if we place , the European brain, , the Bosjesman brain, and , the orang brain, in a series, the differences between and , so far as they have been ascertained, are of the same nature as the chief of those between and ".

Owen countered Huxley by saying the brains of all human races were really of similar size and intellectual ability, and that the fact that humans had brains that were twice the size of large apes like male gorillas, even though humans had much smaller bodies, made humans distinguishable.

Huxley's campaign ran over two years and was devastatingly successful at persuading the overall scientific community, with each "slaying" being followed by a recruiting drive for the Darwinian cause. The spite lingered. While Owen had argued that humans were distinct from apes by virtue of having large brains, Huxley said that racial diversity blurred any such distinction. In his paper criticising Owen, Huxley directly states:

: ... "if we place , the European brain, , the Bosjesman brain, and , the orang brain, in a series, the differences between and , so far as they have been ascertained, are of the same nature as the chief of those between and ".

Owen countered Huxley by saying the brains of all human races were really of similar size and intellectual ability, and that the fact that humans had brains that were twice the size of large apes like male gorillas, even though humans had much smaller bodies, made humans distinguishable.

Legacy

He was the first director inNatural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

in London and his statue was in the main hall there until 2009, when it was replaced with a statue of Darwin.

A bust of Owen by Alfred Gilbert (1896) is held in the Hunterian Museum, London.

A species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of Central American lizard, '' Diploglossus owenii'', was named in his honour by French herpetologists André Marie Constant Duméril

André Marie Constant Duméril (1 January 1774 – 14 August 1860) was a French zoologist. He was professor of anatomy at the National Museum of Natural History (France), Muséum national d'histoire naturelle from 1801 to 1812, when he became pr ...

and Gabriel Bibron

Gabriel Bibron (20 October 1805 – 27 March 1848) was a French zoologist and herpetologist. He was born in Paris. The son of an employee of the Museum national d'histoire naturelle, he had a good foundation in natural history and was ...

in 1839.

The Sir Richard Owen Wetherspoons

J D Wetherspoon (branded variously as Wetherspoon or Wetherspoons, and colloquially known as Spoons) is a British pub company operating in the United Kingdom, Isle of Man and Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The company was founded in 1979 by Tim ...

pub in central Lancaster is named in his honour.

Conflicts with his peers

Owen has been described by some as a malicious, dishonest and hateful individual. He has been described in one biography as being a "social experimenter with a penchant for sadism. Addicted to controversy and driven by arrogance and jealousy". Deborah Cadbury stated that Owen possessed an "almost fanatical egoism with a callous delight in savaging his critics." An Oxford University professor once described Owen as "a damned liar. He lied for God and for malice".Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons, MRCS Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was an English obstetrician, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstr ...

said it was "a pity a man so talented should be so dastardly and envious". Richard Broke Freeman described him as "the most distinguished vertebrate zoologist and palaeontologist ... but a most deceitful and odious man". Charles Darwin stated that "No one fact tells so strongly against Owen ... as that he has never reared one pupil or follower."

Owen famously credited himself and Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

with the discovery of the ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species found worldwide have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, Taxonomy (bi ...

'', completely excluding any credit for the original discoverer of the dinosaur, Gideon Mantell. This was not the first or last time Owen would falsely claim a discovery as his own. It has also been suggested by some authors that Owen even used his influence in the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

to ensure that many of Mantell's research papers were never published. Owen was finally dismissed from the Royal Society's Zoological Council for plagiarism

Plagiarism is the representation of another person's language, thoughts, ideas, or expressions as one's own original work.From the 1995 ''Random House Dictionary of the English Language, Random House Compact Unabridged Dictionary'': use or close ...

.

Another reason for his criticism of the '' Origin'', some historians claim, was that Owen felt upstaged by Darwin and supporters such as Huxley, and his judgment was clouded by jealousy. Owen in Darwin's opinion was "spiteful, extremely malignant, clever; the Londoners say he is mad with envy because my book is so talked about".

Owen also resorted to the same subterfuge he used against Mantell, writing another anonymous article in the ''

Owen also resorted to the same subterfuge he used against Mantell, writing another anonymous article in the ''Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'', ...

'' in April 1860. In the article, Owen was critical of Darwin for not offering many new observations, and heaped praise (in the third person) upon himself, while being careful not to associate any particular comment with his own name. Owen did praise, however, the ''Origin''Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. An internationally important botanical research and education institution, it employs 1,10 ...

botanical collection (see Attacks on Hooker and Kew), orchestrated by Acton Smee Ayrton:

:"There is no doubt that rivalry resulted between the British Museum, where there was the very important Herbarium of the Department of Botany, and Kew. The rivalry at times became extremely personal, especially between Hooker and Owen ... At the root was Owen's feeling that Kew should be subordinate to the British Museum (and to Owen) and should not be allowed to develop as an independent scientific institution with the advantage of a great botanic garden."

Owen's lost scientific standing was not due solely to his underhanded dealings with colleagues; it was also due to serious errors of scientific judgement that were discovered and publicised. A fine example was his decision to classify man in a separate subclass of the Mammalia (see '' Man's place in nature''). In this, Owen had no supporters at all. Also, his unwillingness to come off the fence concerning evolution became increasingly damaging to his reputation as time went on. Owen continued working after his official retirement at the age of 79, but he never recovered the good opinions he had garnered in his younger days.

Bibliography

* ''Memoir on the Pearly Nautilus'' (1832) * ''Odontography'' (1840–1845) * ''Description of the Skeleton of an Extinct Gigantic Sloth'' (1842) * ''On the Archetype and Homologies of the Vertebrate Skeleton'' (1848) * ''History of British Fossil Reptiles'' (4 vols., 1849–1884) * ''On the Nature of Limbs'' (1849) * ''Palæontology or a Systematic Summary of Extinct Animals and Their Geological Relations'' (1860) * ''Archaeopteryx'' (1863) * ''Anatomy of Vertebrates'' (1866) Image from **Available at Google Books:Volume I, Fishes and Reptiles

Volume II, Birds and Mammals

Volume III, Mammals

* ''Memoir of the Dodo'' (1866) Full book on Wiki commons * ''Monograph of the Fossil Mammalia of the Mesozoic Formations'' (1871) * ''Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa'' (1876) * ''Antiquity of Man as deduced from the Discovery of a Human Skeleton during Excavations of the Docks at Tilbury'' (1884)

References

Further reading

* * * Amundson, Ron, (2007), ''The Changing Role of the Embryo in Evolutionary Thought: Roots of Evo-Devo.'' New York: Cambridge University of Press. * * * * *Cosans, Christopher, (2009), ''Owen's Ape & Darwin's Bulldog: Beyond Darwinism and Creationism''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. * Desmond, Adrian & Moore, James (1991). ''Darwin''. London: Michael Joseph, the Penguin Group. . * Darwin, Francis, editor (1887). ''The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin: Including an Autobiographical Chapter'' (7th Edition). London: John Murray. *Darwin, Francis & Seward, A. C., editors (1903). ''More letters of Charles Darwin: A record of his work in a series of hitherto unpublished letters''. London: John Murray. * * * * Cosans, 2009, pp. 108–111 * * * Richards, Evellen, (1987), "A Question of Property Rights: Richard Owen's Evolutionism Reassessed", ''British Journal for the History of Science'', 20: 129–171. * Rupke, Nicolaas, (1994), ''Richard Owen: Victorian Naturalist.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. * Shindler, Karolyn. ''Richard Owen: the greatest scientist you've never heard of'', The Telegraph, 16 December 2010(accessed 16 December 2010)

External links

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Owen, Richard 1804 births 1892 deaths English anatomists English biologists English palaeontologists English people of Welsh descent Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the Medical College of St Bartholomew's Hospital Employees of the Natural History Museum, London English people of French descent Fellows of the Royal Microscopical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Fullerian Professors of Physiology Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Non-Darwinian evolution People educated at Lancaster Royal Grammar School People from Lancaster, Lancashire Philosophical theists Recipients of the Copley Medal Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Royal Medal winners Wollaston Medal winners 19th-century British biologists People who have lived in Richmond Park Burials at St Andrew's Church, Ham