Reverse Underground Railroad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Reverse Underground Railroad is the name given, sardonically, to the pre-

The 1827 newspaper ''The African Observer'' described how several Philadelphia children were lured on board a small sloop, at anchor in the Delaware River, with the promise of peaches, oranges and watermelons, then immediately put into the hold of the ship in chains, where they took a week long journey by ship. Once landed, they were marched through brushwood, swamp and cornfields to the home of Joe Johnson and Jesse and Patty Cannon, on the line between Delaware and Maryland, where they were 'kept in irons for a considerable amount of time.' From there, they were again put on board another vessel for a week or more, where one of the children heard someone talking about Chesapeake Bay, in Maryland. Once landed, they were marched again for 'many hundred miles' through Alabama until they reached Rocky Springs, Mississippi.

The same article described a chain of Reverse Underground Railroad posts "established from Pennsylvania to Louisiana."Lewis, Enoch, "Kidnapping," The African Observer, Vol. 1–12, p. 39, 1827

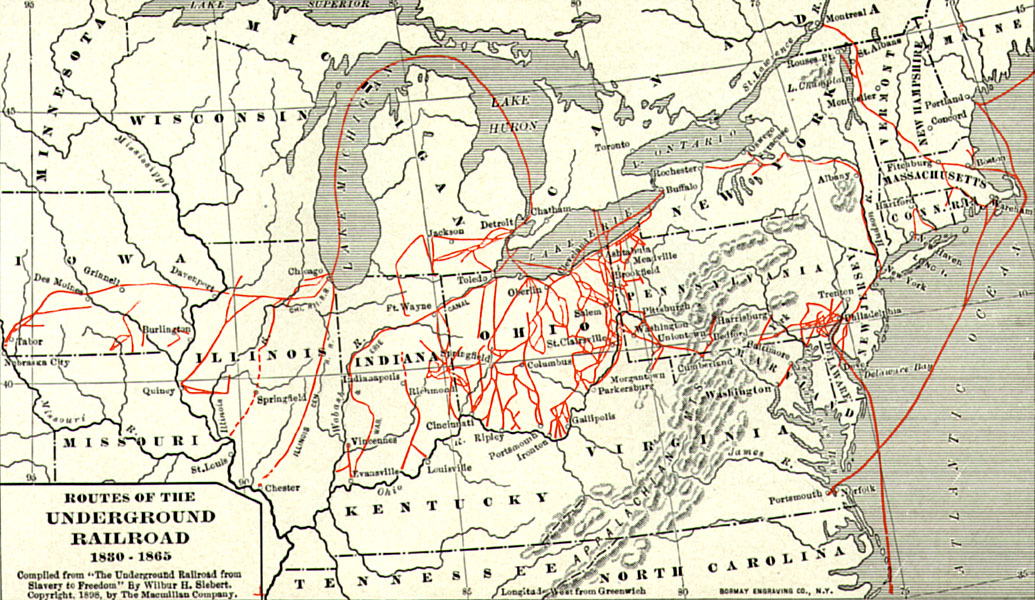

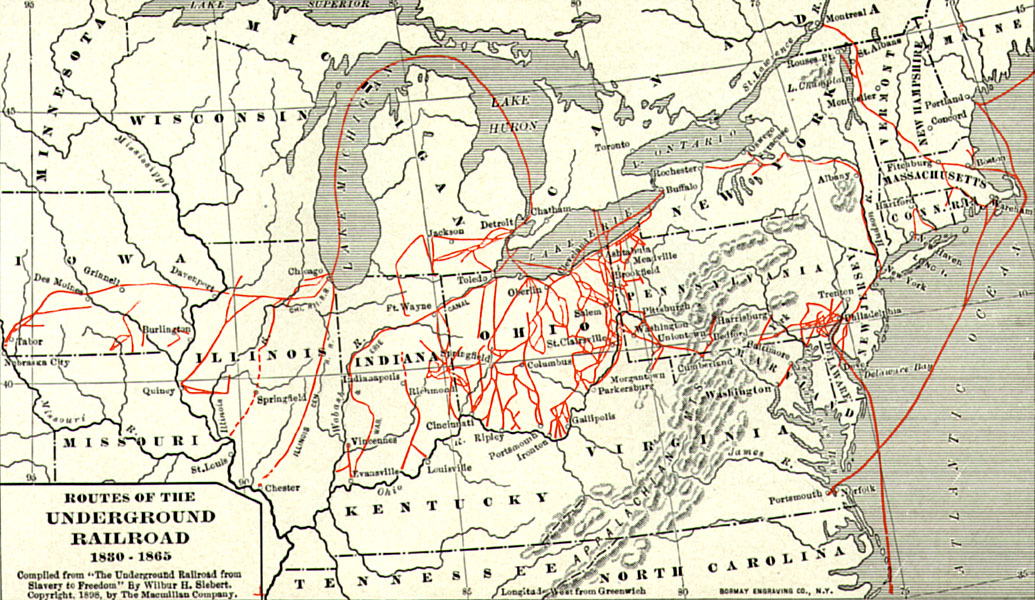

In the West, kidnappers rode the waters of the Ohio River, stealing slaves in Kentucky and kidnapping free people in Southern Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, who were then transported to the slave states.

The 1827 newspaper ''The African Observer'' described how several Philadelphia children were lured on board a small sloop, at anchor in the Delaware River, with the promise of peaches, oranges and watermelons, then immediately put into the hold of the ship in chains, where they took a week long journey by ship. Once landed, they were marched through brushwood, swamp and cornfields to the home of Joe Johnson and Jesse and Patty Cannon, on the line between Delaware and Maryland, where they were 'kept in irons for a considerable amount of time.' From there, they were again put on board another vessel for a week or more, where one of the children heard someone talking about Chesapeake Bay, in Maryland. Once landed, they were marched again for 'many hundred miles' through Alabama until they reached Rocky Springs, Mississippi.

The same article described a chain of Reverse Underground Railroad posts "established from Pennsylvania to Louisiana."Lewis, Enoch, "Kidnapping," The African Observer, Vol. 1–12, p. 39, 1827

In the West, kidnappers rode the waters of the Ohio River, stealing slaves in Kentucky and kidnapping free people in Southern Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, who were then transported to the slave states.

File:Kidnapping a free black to be sold into slavery, 1834 woodcut.jpg, Kidnapping of a free black, in the U.S. free states, to be sold into Southern slavery, from an 1834

The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved from Womb to Grave in the Building of a Nation

'. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2017. *Blackmore, Jacqueline. ''African American and Race Relations in Gallatin County, Illinois: from the 18th century to 1870''. Ann Arbor: Proquest, 1996. *Campbell, Stanley W.

The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850–1860

'. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press Books, 2012. *Collins, Winfield Hazlitt.

The domestic slave trade of the southern states

'. Broadway Publishing Company, 1904. *Diggins, Milt.

Stealing Freedom Along the Mason–Dixon Line: Thomas McCreary, the Notorious Slave Catcher from Maryland

'. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015. *Fiske, David.

Solomon Northup's Kindred: The Kidnapping of Free Citizens before the Civil War: The Kidnapping of Free Citizens before the Civil War

'. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2016. *Fiske, David, Clifford W Brown Jr., and Rachel Seligman.

Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years A Slave: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave

'. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2013 *Giles, Ted. ''Patty Cannon: Woman of Mystery''. Easton Publishing Company, 1965. *Harrold, Stanley.

Border War: Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War

'. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010. *Maddox, Lucy. ''The Parker Sisters: A Border Kidnapping''. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2016. *Morgan, Michael.

Delmarva's Patty Cannon: The Devil on the Nanticoke

'. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2015. *Musgrave, Jon. ''Slaves, Salt, Sex and Mr. Crenshaw: The Real Story of the Old Slave House and America's Reverse Underground R. R.'' IllinoisHistory.com, 2004. *Musgrave, Jon.

. Research Paper presented at Dr. John Y. Simon's Seminar in Illinois History at

Potts Hill Gang, Sturdivant Gang, and Ford's Ferry Gang Rogue's Gallery, Hardin County in IllinoisGenWeb

Springfield, IL: The Illinois Gen Web Project, 2018. *Penick, James L. ''The great western land pirate: John A. Murrell in legend and history''. Columbia, MO:

Reverend Devil: Master Criminal of the Old South

'. Gretna, LA: Publisher Pelican Publishing, 1941. *Slaughter, Thomas P.

Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and Racial Violence in the Antebellum North

'. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1994. *Stewart, Virgil A.

The history of Virgil A. Stewart: and his adventure in capturing and exposing the great "western land pirate" and his gang...

' New York, NY: Harper and Brothers, 1836. * Wellman, Paul L. ''Spawn of Evil''. New York, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1964. *Wilson, Carol.

Freedom at Risk: The Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780–1865

'. Lexington, KY:

"Reverse Underground Railroad' Is Touted For Preservation," ''Chicago Tribune''

* ttp://www.communityinformaticsprojects.org/396/Gallatin/reverseunderground.html Reverse Underground Railroad in Illinois – A Myth of a Free Statebr>''Kidnapping'', PBS Documentary

Slavery in the United States Underground Railroad

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

practice of kidnapping in free states not only fugitive slaves

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th century to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freed ...

but free blacks as well, transporting them to slave states, and selling them as slaves, or occasionally getting a reward for return of a fugitive. Those who used the term were pro-slavery and angered at an "underground railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

" helping slaves escape. Also, the so-called "reverse underground railroad" had incidents but not a network, and its activities did not always take place in secret. Rescues of blacks being kidnapped were unusual.

Three types of kidnapping methods were employed: physical abduction, inveiglement (kidnapping through trickery) of free blacks, and apprehension of fugitives. The Reverse Underground Railroad operated for 85 years, from 1780 to 1865. The name is a reference to the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

, the informal network of abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

and sympathizers who helped smuggle escaped slaves to freedom, generally in Canada but also in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

where slavery had been abolished.

Prevalence

Free African Americans were often kidnapped from the southernmost free states, along the borders of the slave states ofDelaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, and Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

, but kidnapping was also prevalent in states further north, such as New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

, as well as in abolition-minded regions of some Southern states, such as Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

.

New York and Pennsylvania

Free blacks in New York City andPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

were particularly vulnerable to kidnapping. In New York, a gang known as 'the black-birders' regularly waylaid men, women and children, sometimes with the support and participation of policemen and city officials. In Philadelphia, black newspapers frequently ran missing children notices, including one for the 14-year-old daughter of the newspaper's editor. Children were particularly susceptible to kidnapping; in a two-year period, at least a hundred children were abducted in Philadelphia alone.

Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia

From 1811 to 1829, Martha "Patty" Cannon was the leader of a gang that kidnapped slaves and free blacks, from theDelmarva Peninsula

The Delmarva Peninsula, or simply Delmarva, is a large peninsula and proposed state on the East Coast of the United States, occupied by the vast majority of the state of Delaware and parts of the Eastern Shore regions of Maryland and Virginia. ...

of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

and transported and sold them to plantation owners located further south. She was indicted for four murders

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the c ...

in 1829 and died in prison, while awaiting trial, purportedly a suicide via arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, b ...

poison

Poison is a chemical substance that has a detrimental effect to life. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figuratively, with a broa ...

ing.

Illinois

John Hart Crenshaw was a large landowner, salt maker, andslave trader

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and religions from ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The social, economic, and legal positions of e ...

, from the 1820s to the 1850s, based out of the southeastern part of Illinois in Gallatin County and a business associate of Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

lawman and outlaw, James Ford. Crenshaw and Ford were allegedly kidnapping free blacks in southeastern Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

and selling them in the slave state of Kentucky. Although Illinois was a free state, Crenshaw leased the salt works in nearby Equality, Illinois

Equality is a village in Gallatin County, Illinois, United States. The population was 595 at the 2010 census, down from 721 at the 2000 census. Near the village are two points of interest, the Crenshaw House and the Garden of the Gods Wilder ...

from the U.S. Government, which permitted the use of slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

for the arduous labor of hauling and boiling salt brine water from local salt springs to produce salt. Due to Crenshaw's keeping and "breeding

Breeding is sexual reproduction that produces offspring, usually animals or plants. It can only occur between a male and a female animal or plant.

Breeding may refer to:

* Animal husbandry, through selected specimens such as dogs, horses, and r ...

" of slaves and kidnapping of free blacks, who were then pressed into slavery, his house became popularly known as The Old Slave House

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

.

Other cases of the Reverse Underground Railroad in Illinois occurred in the southwestern and western parts of the state, along the Mississippi River bordering the slave state of Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

. In 1860, John and Nancy Curtis were arrested for trying to kidnap their own freed slaves in Johnson County, Illinois

Johnson County is a county in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2010 census, it has a population of 12,582. Its county seat is Vienna. It is located in the southern portion of Illinois known locally as " Little Egypt".

History

Joh ...

to sell back into slavery in Missouri. Free blacks were also kidnapped in Jersey County, Illinois

Jersey County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. At the 2020 census, it had a population of 21,512. The county seat and largest community is Jerseyville, with a population of 8,337 in 2010. The county's smallest incorporated c ...

and taken away to be sold as slaves in Missouri.

Southern states

Black sailors who voyaged to southern states faced the threat of kidnapping.South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

passed the Negro Seamen Act in 1822 out of fear that free black sailors would inspire slave revolts, requiring that they be incarcerated while their ship was docked. This could lead to black sailors being sold into slavery if their captains did not pay fees resulting from them being jailed, or if their freedom papers were lost.

In the 1820s–1830s, John A. Murrell led an outlaw gang in western Tennessee. He was once caught with a freed slave living on his property. His tactics were to kidnap slaves from their plantations, promise them their freedom, and instead sell them back to other slave owners. If Murrell was in danger of being caught with kidnapped slaves, he would kill the slaves to escape being arrested with stolen property, which was considered a major crime in the Southern United States. In 1834, Murrell was arrested and sentenced to ten years in the Tennessee State Penitentiary

Tennessee State Prison is a former correctional facility located six miles west of downtown Nashville, Tennessee on Cockrill Bend. It opened in 1898 and has been closed since 1992 because of overcrowding concerns. The mothballed facility was seve ...

in Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and th ...

for slave-stealing.

Routes

The 1827 newspaper ''The African Observer'' described how several Philadelphia children were lured on board a small sloop, at anchor in the Delaware River, with the promise of peaches, oranges and watermelons, then immediately put into the hold of the ship in chains, where they took a week long journey by ship. Once landed, they were marched through brushwood, swamp and cornfields to the home of Joe Johnson and Jesse and Patty Cannon, on the line between Delaware and Maryland, where they were 'kept in irons for a considerable amount of time.' From there, they were again put on board another vessel for a week or more, where one of the children heard someone talking about Chesapeake Bay, in Maryland. Once landed, they were marched again for 'many hundred miles' through Alabama until they reached Rocky Springs, Mississippi.

The same article described a chain of Reverse Underground Railroad posts "established from Pennsylvania to Louisiana."Lewis, Enoch, "Kidnapping," The African Observer, Vol. 1–12, p. 39, 1827

In the West, kidnappers rode the waters of the Ohio River, stealing slaves in Kentucky and kidnapping free people in Southern Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, who were then transported to the slave states.

The 1827 newspaper ''The African Observer'' described how several Philadelphia children were lured on board a small sloop, at anchor in the Delaware River, with the promise of peaches, oranges and watermelons, then immediately put into the hold of the ship in chains, where they took a week long journey by ship. Once landed, they were marched through brushwood, swamp and cornfields to the home of Joe Johnson and Jesse and Patty Cannon, on the line between Delaware and Maryland, where they were 'kept in irons for a considerable amount of time.' From there, they were again put on board another vessel for a week or more, where one of the children heard someone talking about Chesapeake Bay, in Maryland. Once landed, they were marched again for 'many hundred miles' through Alabama until they reached Rocky Springs, Mississippi.

The same article described a chain of Reverse Underground Railroad posts "established from Pennsylvania to Louisiana."Lewis, Enoch, "Kidnapping," The African Observer, Vol. 1–12, p. 39, 1827

In the West, kidnappers rode the waters of the Ohio River, stealing slaves in Kentucky and kidnapping free people in Southern Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, who were then transported to the slave states.

Travel conditions

Many kidnapped black people were marched to the South on foot. The men were chained together to prevent escape, while the women and children tended to be less restricted.Prevention and rescue

As early as 1775,Anthony Benezet

Anthony Benezet, born Antoine Bénézet (January 31, 1713May 3, 1784), was a French-American abolitionist and educator who was active in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. One of the early American abolitionists, Benezet founded one of the world's fir ...

and others met in Philadelphia and organized the

Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully held in Bondage to focus on intervention in the cases of blacks and Indians who claimed to have been illegally enslaved. This group was later reorganized as the biracial Pennsylvania Abolition Society. The Protecting Society of Philadelphia, an auxiliary of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, was established in 1827 for "the prevention of kidnapping and man-stealing". In January, 1837, The New York Vigilance Committee

A vigilance committee was a group formed of private citizens to administer law and order or exercise power through violence in places where they considered governmental structures or actions inadequate. A form of vigilantism and often a more stru ...

, established because any free black person was at risk for being kidnapped, reported that it had protected 335 persons from slavery. David A. Ruggles, a black newspaper editor and treasurer of the organization, writes in his paper of his futile attempts to convince two New York judges to prevent illegal kidnapping, as well as a daring successful physical rescue of a young girl named Charity Walker from the New York home of her captors.

State and city governments had difficulty in preventing kidnappings, even before the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most con ...

. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society compared records of apprehended blacks to try to free those who were wrongfully detained, kept a list of missing people who were potential abductees, and formed the Committee on Kidnapping. However, these efforts proved to be expensive, rendering them unable to work effectively due to their lack of sustainability.

Citizens, particularly free black citizens, were active in lobbying local governments to adopt stronger measures against kidnapping. In 1800, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones sent a petition to Congress from 73 prominent free Black citizens urging a stop to the kidnappings. It was ignored. Due to the lack of effectiveness from government institutions, free blacks were frequently forced to use their own methods to protect themselves and their families. Such methods included keeping proof of their freedom with them at all times and avoiding contact with strangers as well as certain areas. Vigilante groups were also formed to attack kidnappers, including black kidnappers, the latter of whom were universally condemned by the free African-American community.

From Philadelphia, high constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

Samuel Parker Garrigues took several trips to Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

states at the behest of mayor Joseph Watson to rescue children and adults who had been kidnapped from the city's streets. He also successfully went after their abductors. One such case was Charles Bailey, kidnapped at fourteen in 1825 and finally rescued by Garrigues after a three-year search. Unfortunately, the beaten and emaciated youth died a few days after being brought back to Philadelphia. Garrigues was able to find and arrest Bailey's abductor, Captain John Smith, alias Thomas Collins, head of "The Johnson Gang". He also tracked down and arrested John Purnell of the Patty Cannon gang. Watson publicized the hunt for the kidnappers in several newspapers, offering a $500 reward. On one occasion, a courageous 15 year old Black boy named Sam Scomp spoke out about his kidnapping during his attempted sale to a white southern planter named John Hamilton. The planter himself contacted Mayor Watson to arrange a rescue of the boy and another kidnapped youth.

In popular culture

In 1853, Solomon Northrup published ''Twelve Years A Slave

''Twelve Years a Slave'' is an 1853 memoir and slave narrative by American Solomon Northup as told to and written by David Wilson. Northup, a black man who was born free in New York state, details himself being tricked to go to Washington, D. ...

'', a memoir of his kidnapping from New York and twelve years spent as a slave in Louisiana. His book sold 30,000 copies upon release. His narrative was made into a 2013 film, which won three Academy Awards

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

.Cieply, Michael; Barnesmarch, Brooks (March 2, 2014). "‘12 Years a Slave’ Claims Best Picture Oscar". The New York Times. ''Comfort: A Novel of the Reverse Underground Railroad'' by H. A. Maxson and Claudia H. Young, came out in 2014.

Abolitionist publications frequently used accounts of people who were kidnapped into slavery for their publications. Notable works that published these accounts include The ''African Observer'', a monthly publication that used firsthand accounts to demonstrate the evils of slavery, as well as ''Isaac Hopper's Tales of Oppression'', a compilation by the abolitionist Isaac Hopper

Isaac Tatem Hopper (December 3, 1771 – May 7, 1852) was an American abolitionist who was active in Philadelphia in the anti-slavery movement and protecting fugitive slaves and free blacks from slave kidnappers. He was also co-founder of Child ...

of kidnapping accounts.

Notable illegal slave trader kidnappers and illegal slave breeders

* Patty Cannon and Cannon-Johnson Gang * John Hart Crenshaw * John A. Murrell * "Uncle Bob" WilsonNotable victims

*Solomon Northup

Solomon Northup (born July 10, 1807-1808) was an American abolitionist and the primary author of the memoir '' Twelve Years a Slave''. A free-born African American from New York, he was the son of a freed slave and a free woman of color. A f ...

Gallery

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

abolitionist anti-slavery almanac

An almanac (also spelled ''almanack'' and ''almanach'') is an annual publication listing a set of current information about one or multiple subjects. It includes information like weather forecasts, farmers' planting dates, tide tables, and othe ...

.

File:Slave kidnap post 1851 boston.jpg, An April 24, 1851 abolitionist poster warning the "Colored People of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

" about policemen acting as "Kidnappers

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the p ...

and Slave Catchers

In the United States a slave catcher was a person employed to track down and return escaped slaves to their enslavers. The first slave catchers in the Americas were active in European colonies in the West Indies during the sixteenth century. I ...

".

File:Patty Cannon.jpg, Patty Cannon

Patty Cannon, whose birth name may have been Lucretia Patricia Hanly (c. 1759/1760 or 1769 – May 11, 1829), was an illegal slave trader, murderer and the co-leader of the Cannon–Johnson Gang of Maryland–Delaware. The group operated for a ...

of the Delmarva Peninsula

The Delmarva Peninsula, or simply Delmarva, is a large peninsula and proposed state on the East Coast of the United States, occupied by the vast majority of the state of Delaware and parts of the Eastern Shore regions of Maryland and Virginia. ...

of Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

.

File:John-A.-Murrell-Portrait.jpg, John A. Murrell of western Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

.

File:John&SinaCrenshaw.jpg, John Hart Crenshaw, of southeastern Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

, with his wife, Francine "Sina" Taylor.

File:The Old Slave House.jpg, John Hart Crenshaw's Hickory Hill mansion

A mansion is a large dwelling house. The word itself derives through Old French from the Latin word ''mansio'' "dwelling", an abstract noun derived from the verb ''manere'' "to dwell". The English word '' manse'' originally defined a property l ...

, in Gallatin County, Illinois

Gallatin County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 4,828, making it the third-least populous county in Illinois. Its county seat is Shawneetown. It is located in the southern ...

, infamously known as the " Old Slave House".

File:Solomon_Northup_001.jpg, Solomon Northup

Solomon Northup (born July 10, 1807-1808) was an American abolitionist and the primary author of the memoir '' Twelve Years a Slave''. A free-born African American from New York, he was the son of a freed slave and a free woman of color. A f ...

, a free black born in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

who was later kidnapped by slave catchers.

File:Solomon Northrup illustration.jpg, An illustration from ''Twelve Years A Slave'', the memoir of Solomon Northup

Solomon Northup (born July 10, 1807-1808) was an American abolitionist and the primary author of the memoir '' Twelve Years a Slave''. A free-born African American from New York, he was the son of a freed slave and a free woman of color. A f ...

, 1853: "Rescues Solomon from Hanging".

File:Slaves auction Virginia 1861.jpg, A typical 19th century slave auction in the Southern United States.

See also

*Black Codes (United States)

The Black Codes, sometimes called the Black Laws, were laws which governed the conduct of African Americans (free and freed blacks). In 1832, James Kent wrote that "in most of the United States, there is a distinction in respect to political p ...

* Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most con ...

* Judicial aspects of race in the United States

* Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the S ...

* Delphine LaLaurie

* Solomon Northup

Solomon Northup (born July 10, 1807-1808) was an American abolitionist and the primary author of the memoir '' Twelve Years a Slave''. A free-born African American from New York, he was the son of a freed slave and a free woman of color. A f ...

* Racial segregation in the United States

In the United States, racial segregation is the systematic separation of facilities and services such as housing, healthcare, education, employment, and transportation on racial grounds. The term is mainly used in reference to the legally ...

* Slave catcher

In the United States a slave catcher was a person employed to track down and return escaped slaves to their enslavers. The first slave catchers in the Americas were active in European colonies in the West Indies during the sixteenth century. I ...

* Slave codes

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

Most slave codes were concerned with the rights and duties of free people in regards to ensla ...

* Sundown town

Sundown towns, also known as sunset towns, gray towns, or sundowner towns, are all-white municipalities or neighborhoods in the United States that practice a form of racial segregation by excluding non-whites via some combination of discriminator ...

* Slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Sla ...

* Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

References

{{Reflist * Berry, Daina Ramey.The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved from Womb to Grave in the Building of a Nation

'. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2017. *Blackmore, Jacqueline. ''African American and Race Relations in Gallatin County, Illinois: from the 18th century to 1870''. Ann Arbor: Proquest, 1996. *Campbell, Stanley W.

The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850–1860

'. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press Books, 2012. *Collins, Winfield Hazlitt.

The domestic slave trade of the southern states

'. Broadway Publishing Company, 1904. *Diggins, Milt.

Stealing Freedom Along the Mason–Dixon Line: Thomas McCreary, the Notorious Slave Catcher from Maryland

'. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015. *Fiske, David.

Solomon Northup's Kindred: The Kidnapping of Free Citizens before the Civil War: The Kidnapping of Free Citizens before the Civil War

'. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2016. *Fiske, David, Clifford W Brown Jr., and Rachel Seligman.

Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years A Slave: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave

'. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2013 *Giles, Ted. ''Patty Cannon: Woman of Mystery''. Easton Publishing Company, 1965. *Harrold, Stanley.

Border War: Fighting over Slavery before the Civil War

'. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010. *Maddox, Lucy. ''The Parker Sisters: A Border Kidnapping''. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2016. *Morgan, Michael.

Delmarva's Patty Cannon: The Devil on the Nanticoke

'. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2015. *Musgrave, Jon. ''Slaves, Salt, Sex and Mr. Crenshaw: The Real Story of the Old Slave House and America's Reverse Underground R. R.'' IllinoisHistory.com, 2004. *Musgrave, Jon.

. Research Paper presented at Dr. John Y. Simon's Seminar in Illinois History at

Southern Illinois University

Southern Illinois University is a system of public universities in the southern region of the U.S. state of Illinois. Its headquarters is in Carbondale, Illinois.

Board of trustees

The university is governed by the nine member SIU Board of Tr ...

at Carbondale, April–May 1997, Carbondale, IL.

*Musgrave, Jon.Potts Hill Gang, Sturdivant Gang, and Ford's Ferry Gang Rogue's Gallery, Hardin County in IllinoisGenWeb

Springfield, IL: The Illinois Gen Web Project, 2018. *Penick, James L. ''The great western land pirate: John A. Murrell in legend and history''. Columbia, MO:

University of Missouri Press

The University of Missouri Press is a university press operated by the University of Missouri in Columbia, Missouri and London, England; it was founded in 1958 primarily through the efforts of English professor William Peden. Many publications a ...

, 1981.

*Phares, Ross. Reverend Devil: Master Criminal of the Old South

'. Gretna, LA: Publisher Pelican Publishing, 1941. *Slaughter, Thomas P.

Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and Racial Violence in the Antebellum North

'. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1994. *Stewart, Virgil A.

The history of Virgil A. Stewart: and his adventure in capturing and exposing the great "western land pirate" and his gang...

' New York, NY: Harper and Brothers, 1836. * Wellman, Paul L. ''Spawn of Evil''. New York, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1964. *Wilson, Carol.

Freedom at Risk: The Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780–1865

'. Lexington, KY:

University Press of Kentucky

The University Press of Kentucky (UPK) is the scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth of Kentucky, and was organized in 1969 as successor to the University of Kentucky Press. The university had sponsored scholarly publication since 1943. In 1 ...

, 1994.

External links

"Reverse Underground Railroad' Is Touted For Preservation," ''Chicago Tribune''

* ttp://www.communityinformaticsprojects.org/396/Gallatin/reverseunderground.html Reverse Underground Railroad in Illinois – A Myth of a Free Statebr>''Kidnapping'', PBS Documentary

Slavery in the United States Underground Railroad