Restoration literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Restoration literature is the

Restoration literature is the

in ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' (2006). Ed. E. A. Livingstone. Oxford Reference Online (subscription required), Oxford University Press. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Courtiers also received an exposure to the

The Age of Dryden: The Restoration Drama: The King’s and the Duke of York’s Companies “Created” after it

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Drama was public and a matter of royal concern, and therefore both theatres were charged with producing a certain number of old plays, and Davenant was charged with presenting material that would be morally uplifting. Additionally, the position of Poet Laureate was recreated, complete with payment by a barrel of "sack" ( Spanish white wine), and the requirement for birthday odes. Charles II was a man who prided himself on his wit and his worldliness. He was well known as a philanderer as well. Highly witty, playful, and sexually wise poetry thus had court sanction. Charles and his brother James, the

Sir William Davenant was the first Restoration poet to attempt an epic. His unfinished '' Gondibert'' was of epic length, and it was admired by Hobbes.Thompson, A. Hamilton.

Sir William Davenant was the first Restoration poet to attempt an epic. His unfinished '' Gondibert'' was of epic length, and it was admired by Hobbes.Thompson, A. Hamilton.

Cavalier and Puritan: Writers of the Couplet: Sir William D’Avenant; ''Gondibert''

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. However, it also used the

Aphra Behn modelled the rake Willmore in her play ''The Rover'' on Rochester;Willmore may have also been based on Behn's lover John Hoyle.

Aphra Behn modelled the rake Willmore in her play ''The Rover'' on Rochester;Willmore may have also been based on Behn's lover John Hoyle.

Behn, Mrs Afra

in ''The Oxford Companion to English Literature'' (2000). Ed. Margaret Drabble. Oxford Reference Online (subscription required), Oxford University Press. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. and while she was best known publicly for her drama (in the 1670s, only Dryden's plays were staged more often than hers), Behn wrote a great deal of poetry that would be the basis of her later reputation. Edward Bysshe would include numerous quotations from her verse in his ''Art of English Poetry'' (1702). While her poetry was occasionally sexually frank, it was never as graphic or intentionally lurid and titillating as Rochester's. Rather, her poetry was, like the court's ethos, playful and honest about sexual desire. One of the most remarkable aspects of Behn's success in court poetry, however, is that Behn was herself a commoner. She had no more relation to peers than Dryden, and possibly quite a bit less. As a woman, a commoner, and If Behn is a curious exception to the rule of noble verse, Robert Gould breaks that rule altogether. Gould was born of a common family and

If Behn is a curious exception to the rule of noble verse, Robert Gould breaks that rule altogether. Gould was born of a common family and

William Temple, after he retired from being what today would be called Secretary of State, wrote several bucolic prose works in praise of retirement, contemplation, and direct observation of nature. He also brought the Ancients and Moderns quarrel into English with his ''Reflections on Ancient and Modern Learning''. The debates that followed in the wake of this quarrel would inspire many of the major authors of the first half of the 18th century (most notably Swift and

William Temple, after he retired from being what today would be called Secretary of State, wrote several bucolic prose works in praise of retirement, contemplation, and direct observation of nature. He also brought the Ancients and Moderns quarrel into English with his ''Reflections on Ancient and Modern Learning''. The debates that followed in the wake of this quarrel would inspire many of the major authors of the first half of the 18th century (most notably Swift and

Sporadic essays combined with news had been published throughout the Restoration period, but ''The Athenian Mercury'' was the first regularly published periodical in England. John Dunton and the "Athenian Society" (actually a mathematician, minister, and philosopher paid by Dunton for their work) began publishing in 1691, just after the reign of William III and

Sporadic essays combined with news had been published throughout the Restoration period, but ''The Athenian Mercury'' was the first regularly published periodical in England. John Dunton and the "Athenian Society" (actually a mathematician, minister, and philosopher paid by Dunton for their work) began publishing in 1691, just after the reign of William III and

Behn's first novel was '' Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister'' in 1684. This was an epistolary novel documenting the amours of a scandalous nobleman who was unfaithful to his wife with her sister (thus making his lover his sister-in-law rather than biological sister). The novel is highly romantic, sexually explicit, and political. Behn wrote the novel in two parts, with the second part showing a distinctly different style from the first. Behn also wrote several "Histories" of fictional figures, such as her ''The History of a Nun''. As the genre of "novel" did not exist, these histories were prose fictions based on biography. However, her most famous novel was '' Oroonoko'' in 1688. This was a fictional biography, published as a "true history", of an African king who had been enslaved in

Behn's first novel was '' Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister'' in 1684. This was an epistolary novel documenting the amours of a scandalous nobleman who was unfaithful to his wife with her sister (thus making his lover his sister-in-law rather than biological sister). The novel is highly romantic, sexually explicit, and political. Behn wrote the novel in two parts, with the second part showing a distinctly different style from the first. Behn also wrote several "Histories" of fictional figures, such as her ''The History of a Nun''. As the genre of "novel" did not exist, these histories were prose fictions based on biography. However, her most famous novel was '' Oroonoko'' in 1688. This was a fictional biography, published as a "true history", of an African king who had been enslaved in

The return of the stage-struck Charles II to power in 1660 was a major event in English theatre history. As soon as the previous Puritan regime's ban on public stage representations was lifted, the drama recreated itself quickly and abundantly. Two theatre companies, the King's and the Duke's Company, were established in London, with two luxurious playhouses built to designs by

The return of the stage-struck Charles II to power in 1660 was a major event in English theatre history. As soon as the previous Puritan regime's ban on public stage representations was lifted, the drama recreated itself quickly and abundantly. Two theatre companies, the King's and the Duke's Company, were established in London, with two luxurious playhouses built to designs by

Critical and Historical Essays — Volume 2

'. Retrieved on 27 February 2007. and the standard reference work of the early 20th century, ''The Cambridge History of English and American Literature'', dismissed the tragedy as being of "a level of dulness and lubricity never surpassed before or since".Bartholomew, A. T. and Peterhouse, M. A.

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Today, the Restoration total theatre experience is again valued, both by postmodern literary critics and on the stage.

An Account of the Ensuing Poem

prefixed to ''Annus Mirabilis'', from Project Gutenberg. Prepared from ''The Poetical Works of John Dryden'' (1855), in Library Edition of the British Poets edited George Gilfillan, vol. 1. Retrieved 18 June 2005. *Dryden, John (originally published in 1670)

Of Heroic Plays, an Essay

(The preface to ''The Conquest of Granada''), in ''The Works of John Dryden'', Volume 04 (of 18) from Project Gutenberg. Prepared from Walter Scott's edition. Retrieved 18 June 2005. *Dryden, John

Discourses on Satire and Epic Poetry

from Project Gutenberg, prepared from the 1888 Cassell & Company edition. This volume contains "A Discourse on the Original and Progress of Satire", prefixed to ''The Satires of Juvenal, Translated'' (1692) and "A Discourse on Epic Poetry", prefixed to the translation of Virgil's ''Aeneid'' (1697). Retrieved 18 June 2005. *Holman, C. Hugh and Harmon, William (eds.) (1986). ''A Handbook to Literature''. New York: Macmillan Publishing. *Howe, Elizabeth (1992). ''The First English Actresses: Women and Drama 1660–1700''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. *Hume, Robert D. (1976). ''The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. *Hunt, Leigh (ed.) (1840). ''The Dramatic Works of Wycherley, Congreve, Vanbrugh and Farquhar''. *Miller, H. K., G. S. Rousseau and Eric Rothstein, ''The Augustan Milieu: Essays Presented to Louis A. Landa'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970). *Milhous, Judith (1979). ''Thomas Betterton and the Management of Lincoln's Inn Fields 1695–1708''. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. *Porter, Roy (2000). ''The Creation of the Modern World''. New York: W. W. Norton. *Roots, Ivan (1966). ''The Great Rebellion 1642–1660''. London: Sutton & Sutton. *Rosen, Stanley (1989). ''The Ancients and the Moderns: Rethinking Modernity''. Yale UP. *Sloane, Eugene H. ''Robert Gould: seventeenth century satirist.'' Philadelphia: U Pennsylvania Press, 1940. *Tillotson, Geoffrey and Fussell, Paul (eds.) (1969). ''Eighteenth-Century English Literature''. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Jovanovich. *Todd, Janet (2000). ''The Secret Life of Aphra Behn''. London: Pandora Press. *Ward, A. W, & Trent, W. P. et al. (1907–21).

The Cambridge History of English and American Literature

'. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. Retrieved 11 June 2005. {{English literature 17th-century literature of England Early Modern English literature 05 The Restoration

Restoration literature is the

Restoration literature is the English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from the English-speaking world. The English language has developed over more than 1,400 years. The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian languages, Anglo-Frisian d ...

written during the historical period commonly referred to as the English Restoration

The Stuart Restoration was the reinstatement in May 1660 of the Stuart monarchy in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland. It replaced the Commonwealth of England, established in January 164 ...

(1660–1688), which corresponds to the last years of Stuart reign in England, Scotland, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, and Ireland. In general, the term is used to denote roughly homogeneous styles of literature that centre on a celebration of or reaction to the restored court of Charles II. It is a literature that includes extremes, for it encompasses both ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an Epic poetry, epic poem in blank verse by the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The poem concerns the Bible, biblical story of the fall of man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their ex ...

'' and the Earl of Rochester's '' Sodom'', the high-spirited sexual comedy of '' The Country Wife'' and the moral wisdom of '' The Pilgrim's Progress''. It saw Locke's '' Treatises of Government'', the founding of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, the experiments and holy meditations of Robert Boyle, the hysterical attacks on theatres from Jeremy Collier, and the pioneering of literary criticism

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature's ...

from John Dryden

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration (En ...

and John Dennis. The period witnessed news becoming a commodity, the essay

An essay ( ) is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a Letter (message), letter, a term paper, paper, an article (publishing), article, a pamphlet, and a s ...

developing into a periodical art form, and the beginnings of textual criticism

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts (mss) or of printed books. Such texts may rang ...

.

The dates for Restoration literature are a matter of convention, and they differ markedly from genre

Genre () is any style or form of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other fo ...

to genre. Thus, the "Restoration" in drama

Drama is the specific Mode (literature), mode of fiction Mimesis, represented in performance: a Play (theatre), play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on Radio drama, radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a g ...

may last until 1700, while in poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

it may last only until 1666 (see 1666 in poetry) and the '' annus mirabilis''; and in prose it might end in 1688, with the increasing tensions over succession and the corresponding rise in journalism

Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree of accuracy. The word, a noun, applies to the journ ...

and periodicals

Periodical literature (singularly called a periodical publication or simply a periodical) consists of Publication, published works that appear in new releases on a regular schedule (''issues'' or ''numbers'', often numerically divided into annu ...

, or not until 1700, when those periodicals grew more stabilized. In general, scholars use the term "Restoration" to denote the literature that began and flourished under Charles II, whether that literature was the laudatory ode

An ode (from ) is a type of lyric poetry, with its origins in Ancient Greece. Odes are elaborately structured poems praising or glorifying an event or individual, describing nature intellectually as well as emotionally. A classic ode is structu ...

that gained a new life with restored aristocracy, the eschatological literature that showed an increasing despair among Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

s, or the literature of rapid communication and trade that followed in the wake of England's mercantile empire.

Historical context

During theInterregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of revolutionary breach of legal continuity, discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one m ...

, England had been dominated by Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

literature and the intermittent presence of official censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governmen ...

(for example, Milton's '' Areopagitica'' and his later retraction of that statement). While some of the Puritan ministers of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

wrote poetry that was elaborate and carnal (such as Andrew Marvell's poem, " To His Coy Mistress"), such poetry was not published. Similarly, some of the poets who published with the Restoration produced their poetry during the Interregnum. The official break in literary culture caused by censorship and radically moralist standards effectively created a gap in literary tradition. At the time of the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, poetry had been dominated by metaphysical poetry of the John Donne

John Donne ( ; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under Royal Patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's, D ...

, George Herbert

George Herbert (3 April 1593 – 1 March 1633) was an English poet, orator, and priest of the Church of England. His poetry is associated with the writings of the metaphysical poets, and he is recognised as "one of the foremost British devotio ...

, and Richard Lovelace sort. Drama had developed the late Elizabethan theatre

The English Renaissance theatre or Elizabethan theatre was the theatre of England from 1558 to 1642. Its most prominent playwrights were William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson.

Background

The term ''English Renaissance theatr ...

traditions and had begun to mount increasingly topical and political plays (for example, the drama of Thomas Middleton). The Interregnum put a stop, or at least a caesura, to these lines of influence and allowed a seemingly fresh start for all forms of literature after the Restoration.

The last years of the Interregnum were turbulent, as were the last years of the Restoration period, and those who did not go into exile were called upon to change their religious beliefs more than once. With each religious preference came a different sort of literature, both in prose and poetry (the theatres were closed during the Interregnum). When Cromwell died and his son, Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who served as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1658 to 1659. He was the son of Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.

Following his father ...

, threatened to become Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') is a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometime ...

, politicians and public figures scrambled to show themselves as allies or enemies of the new regime. Printed literature was dominated by ode

An ode (from ) is a type of lyric poetry, with its origins in Ancient Greece. Odes are elaborately structured poems praising or glorifying an event or individual, describing nature intellectually as well as emotionally. A classic ode is structu ...

s in poetry, and religious writing in prose. The industry of religious tract writing, despite official efforts, did not reduce its output. Figures such as the founder of the Society of Friends, George Fox

George Fox (July 1624 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 13 January 1691 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) was an English Dissenters, English Dissenter, who was a founder of the Quakers, Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as t ...

, were jailed by the Cromwellian authorities and published at their own peril.

During the Interregnum, the royalist forces attached to the court of Charles I went into exile with the twenty-year-old Charles II and conducted a brisk business in intelligence and fund-raising for an eventual return to England. Some of the royalist ladies installed themselves in convent

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

s in Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

and France that offered safe haven for indigent and travelling nobles and allies. The men similarly stationed themselves in Holland and France, with the court-in-exile being established in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

before setting up more permanently in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. The nobility who travelled with (and later travelled to) Charles II were therefore lodged for more than a decade in the midst of the continent's literary scene. As Holland and France in the 17th century were little alike, so the influences picked up by courtiers in exile and the travellers who sent intelligence and money to them were not monolithic. Charles spent his time attending plays in France, and he developed a taste for Spanish plays. Those nobles living in Holland began to learn about mercantile exchange as well as the tolerant, rationalist prose debates that circulated in that officially tolerant nation. John Bramhall, for example, had been a strongly high church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, Christian liturgy, liturgy, and Christian theology, theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although ...

theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of ...

, and yet, in exile, he debated willingly with Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

and came into the Restored church as tolerant in practice as he was severe in argument.Bramhall, Johnin ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' (2006). Ed. E. A. Livingstone. Oxford Reference Online (subscription required), Oxford University Press. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Courtiers also received an exposure to the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and its liturgy and pageants, as well as, to a lesser extent, Italian poetry

Italian poetry is a category of Italian literature. Italian poetry has its origins in the thirteenth century and has heavily influenced the poetic traditions of many European languages, including that of English.

Features

* Italian prosody is ...

.

Initial reaction

When Charles II became king in 1660, the sense of novelty in literature was tempered by a sense of suddenly participating in European literature in a way that England had not before. One of Charles's first moves was to reopen the theatres and to grantletters patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

giving mandates for the theatre owners and managers. Thomas Killigrew received one of the patents, establishing the King's Company

The King's Company was one of two enterprises granted the rights to mount theatrical productions in London, after the London theatre closure 1642, London theatre closure had been lifted at the start of the English Restoration. It existed from 166 ...

and opening the first patent theatre at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and listed building, Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) an ...

; Sir William Davenant received the other, establishing the Duke of York's theatre company and opening his patent theatre in Lincoln's Inn Fields.Schelling, Felix E.The Age of Dryden: The Restoration Drama: The King’s and the Duke of York’s Companies “Created” after it

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Drama was public and a matter of royal concern, and therefore both theatres were charged with producing a certain number of old plays, and Davenant was charged with presenting material that would be morally uplifting. Additionally, the position of Poet Laureate was recreated, complete with payment by a barrel of "sack" ( Spanish white wine), and the requirement for birthday odes. Charles II was a man who prided himself on his wit and his worldliness. He was well known as a philanderer as well. Highly witty, playful, and sexually wise poetry thus had court sanction. Charles and his brother James, the

Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of List of English monarchs, English (later List of British monarchs, British) monarchs ...

and future King of England, also sponsored mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

and natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

, and so spirited scepticism and investigation into nature were favoured by the court. Charles II sponsored the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, which courtiers were eager to join (for example, the noted diarist Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys ( ; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English writer and Tories (British political party), Tory politician. He served as an official in the Navy Board and Member of Parliament (England), Member of Parliament, but is most r ...

was a member), just as Royal Society members moved in court. Charles and his court had also learned the lessons of exile. Charles was High Church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, Christian liturgy, liturgy, and Christian theology, theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although ...

(and secretly vowed to convert to Roman Catholicism on his death) and James was crypto-Catholic, but royal policy was generally tolerant of religious and political dissenters. While Charles II did have his own version of the Test Act, he was slow to jail or persecute Puritans, preferring merely to keep them from public office (and therefore to try to rob them of their Parliamentary positions). As a consequence, the prose literature of dissent, political theory, and economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

increased in Charles II's reign.

Authors moved in two directions in reaction to Charles's return. On the one hand, there was an attempt at recovering the English literature of the Jacobean period, as if there had been no disruption; but, on the other, there was a powerful sense of novelty, and authors approached Gallic models of literature and elevated the literature of wit (particularly satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of exposin ...

and parody

A parody is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satire, satirical or irony, ironic imitation. Often its subject is an Originality, original work or some aspect of it (theme/content, author, style, e ...

). The novelty would show in the literature of sceptical inquiry, and the Gallicism would show in the introduction of Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism, also spelled Neo-classicism, emerged as a Western cultural movement in the decorative arts, decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiq ...

into English writing and criticism.

Top-down history

The Restoration is an unusual historical period, as its literature is bounded by a specific political event: the restoration of the Stuart monarchy. It is unusual in another way, as well, for it is a time when the influence of that king's presence and personality permeated literary society to such an extent that, almost uniquely, literature reflects the court. The adversaries of the restoration, the Puritans and democrats and republicans, similarly respond to the peculiarities of the king and the king's personality. Therefore, a top-down view of the literary history of the Restoration has more validity than that of most literary epochs. "The Restoration" as a critical concept covers the duration of the effect of Charles and Charles's manner. This effect extended beyond his death, in some instances, and not as long as his life, in others.Poetry

The Restoration was an age of poetry. Not only was poetry the most popular form of literature, but it was also the most ''significant'' form of literature, as poems affected political events and immediately reflected the times. It was, to its own people, an age dominated only by the king, and not by any single genius. Throughout the period, the lyric, ariel, historical, and epic poem was being developed.The English epic

Even without the introduction of Neo-classical criticism, English poets were aware that they had no nationalepic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film defined by the spectacular presentation of human drama on a grandiose scale

Epic(s) ...

. Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; – 13 January 1599 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the House of Tudor, Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is re ...

's ''Faerie Queene

''The Faerie Queene'' is an English Epic poetry, epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books IIII were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 together with books IVVI. ''The Faerie Queene'' is notable for its form: at over 36,000 lines and ov ...

'' was well known, but England, unlike France with '' The Song of Roland'' or Spain with the ''Cantar de Mio Cid

''El Cantar de mio Cid'', or ''El Poema de mio Cid'' ("The Song of My Cid"; "The Poem of My Cid"), is an anonymous '' cantar de gesta'' and the oldest preserved Castilian epic poem. Based on a true story, it tells of the deeds of the Castilian h ...

'' or, most of all, Italy with the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

'', had no epic poem of national origins. Several poets attempted to supply this void.

Sir William Davenant was the first Restoration poet to attempt an epic. His unfinished '' Gondibert'' was of epic length, and it was admired by Hobbes.Thompson, A. Hamilton.

Sir William Davenant was the first Restoration poet to attempt an epic. His unfinished '' Gondibert'' was of epic length, and it was admired by Hobbes.Thompson, A. Hamilton.Cavalier and Puritan: Writers of the Couplet: Sir William D’Avenant; ''Gondibert''

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. However, it also used the

ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and song of Great Britain and Ireland from the Late Middle Ages until the 19th century. They were widely used across Eur ...

form, and other poets, as well as critics, were very quick to condemn this rhyme scheme as unflattering and unheroic (Dryden ''Epic''). The prefaces to ''Gondibert'' show the struggle for a formal epic structure, as well as how the early Restoration saw themselves in relation to Classical literature

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek and Roman literature and their original languages, ...

.

Although today he is studied separately from the Restoration period, John Milton's ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an Epic poetry, epic poem in blank verse by the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The poem concerns the Bible, biblical story of the fall of man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their ex ...

'' was published during that time. Milton no less than Davenant wished to write the English epic, and chose blank verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metre (poetry), metrical but rhyme, unrhymed lines, usually in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th cen ...

as his form. Milton rejected the cause of English exceptionalism: his ''Paradise Lost'' seeks to tell the story of all mankind, and his pride is in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

rather than Englishness.

Significantly, Milton began with an attempt at writing an epic on King Arthur

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Great Britain, Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Wales, Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a le ...

, for that was the matter of English national founding. While Milton rejected that subject, in the end, others made the attempt. Richard Blackmore

Sir Richard Blackmore (22 January 1654 – 9 October 1729), England, English poet and physician, is remembered primarily as the object of satire and as an epic poet, but he was also a respected medical doctor and theologian.

Earlier years

He ...

wrote both a ''Prince Arthur'' and ''King Arthur''. Both attempts were long and soporific, and failed both critically and popularly. Indeed, the poetry was so slow that the author became known as "Never-ending Blackmore" (see Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early ...

's lambasting of Blackmore in '' The Dunciad'').

The Restoration period ended without an English epic. ''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ) is an Old English poetry, Old English poem, an Epic poetry, epic in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translat ...

'' may now be called the English epic, but the work was unknown to Restoration authors, and Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

was incomprehensible to them.

Poetry, verse, and odes

Lyric poetry

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

The term for both modern lyric poetry and modern song lyrics derives from a form of Ancient Greek literature, t ...

, in which the poet speaks of his or her own feelings in the first person and expresses a mood, was not especially common in the Restoration period. Poets expressed their points of view in other forms, usually public or formally disguised poetic forms such as odes, pastoral poetry, and ariel verse. One of the characteristics of the period is its devaluation of individual sentiment and psychology in favour of public utterance and philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

. The sorts of lyric poetry found later in the Churchyard Poets would, in the Restoration, only exist as pastorals.

Formally, the Restoration period had a preferred rhyme scheme. Rhyming couplets in iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter ( ) is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in each line. Meter is measured in small groups of syllables called feet. "Iambi ...

was by far the most popular structure for poetry of all types. Neo-Classicism meant that poets attempted adaptations of Classical meters, but the rhyming couplet in iambic pentameter held a near monopoly. According to Dryden ("Preface to ''The Conquest of Grenada''"), the rhyming couplet in iambic pentameter has the right restraint and dignity for a lofty subject, and its rhyme allowed for a complete, coherent statement to be made. Dryden was struggling with the issue of what later critics in the Augustan period would call "decorum": the fitness of form to subject (q.v. Dryden ''Epic''). It is the same struggle that Davenant faced in his ''Gondibert''. Dryden's solution was a closed couplet in iambic pentameter that would have a minimum of enjambment

In poetry, enjambment (; from the French ''enjamber'') is incomplete syntax at the end of a line; the meaning 'runs over' or 'steps over' from one poetic line to the next, without punctuation. Lines without enjambment are end-stopped. The origin ...

. This form was called the "heroic couplet," because it was suitable for heroic subjects. Additionally, the age also developed the mock-heroic couplet. After 1672 and Samuel Butler's '' Hudibras'', iambic tetrameter couplets with unusual or unexpected rhymes became known as Hudibrastic verse. It was a formal parody

A parody is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satire, satirical or irony, ironic imitation. Often its subject is an Originality, original work or some aspect of it (theme/content, author, style, e ...

of heroic verse, and it was primarily used for satire. Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the Dean (Christianity), dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swi ...

would use the Hudibrastic form almost exclusively for his poetry.

Although Dryden's reputation is greater today, contemporaries saw the 1670s and 1680s as the age of courtier poets in general, and Edmund Waller was as praised as any. Dryden, Rochester, Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

, and Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

dominated verse, and all were attached to the court of Charles. Aphra Behn, Matthew Prior, and Robert Gould, by contrast, were outsiders who were profoundly royalist. The court poets follow no one particular style, except that they all show sexual awareness, a willingness to satirise, and a dependence upon wit to dominate their opponents. Each of these poets wrote for the stage as well as the page. Of these, Behn, Dryden, Rochester, and Gould deserve some separate mention.

Dryden was prolific; and he was often accused of plagiarism. Both before and after his Laureateship, he wrote public odes. He attempted the Jacobean pastoral along the lines of Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebell ...

and Philip Sidney

Sir Philip Sidney (30 November 1554 – 17 October 1586) was an English poet, courtier, scholar and soldier who is remembered as one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan era, Elizabethan age.

His works include a sonnet sequence, ' ...

, but his greatest successes and fame came from his attempts at apologetics for the restored court and the Established Church. His '' Absalom and Achitophel'' and '' Religio Laici'' both served the King directly by making controversial royal actions seem reasonable. He also pioneered the mock-heroic

Mock-heroic, mock-epic or heroi-comic works are typically satires or parodies that mock common Classical stereotypes of heroes and heroic literature. Typically, mock-heroic works either put a fool in the role of the hero or exaggerate the heroic ...

. Although Samuel Butler had invented the mock-heroic in English with ''Hudibras'' (written during the Interregnum but published in the Restoration), Dryden's '' MacFlecknoe'' set up the satirical parody. Dryden was himself not of noble blood, and he was never awarded the honours that he had been promised by the King (nor was he repaid the loans he had made to the King), but he did as much as any peer to serve Charles II. Even when James II came to the throne and Roman Catholicism was on the rise, Dryden attempted to serve the court, and his '' The Hind and the Panther'' praised the Roman church above all others. After that point, Dryden suffered for his conversions, and he was the victim of many satires.

Buckingham wrote some court poetry, but he, like Dorset, was a patron of poetry more than a poet. Rochester, meanwhile, was a prolix and outrageous poet. Rochester's poetry is almost always sexually frank and is frequently political. Inasmuch as the Restoration came after the Interregnum, the very sexual explicitness of Rochester's verse was a political statement and a thumb in the eye of Puritans. His poetry often assumes a lyric pose, as he pretends to write in sadness over his own impotence ("The Disabled Debauchee") or sexual conquests, but most of Rochester's poetry is a parody of an existing, Classically authorised form. He has a mock topographical poem ("Ramble in St James Park", which is about the dangers of darkness for a man intent on copulation and the historical compulsion of that plot of ground as a place for fornication), several mock odes ("To Signore Dildo," concerning the public burning of a crate of "contraband" from France on the London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

docks), and mock pastorals. Rochester's interest was in inversion, disruption, and the superiority of wit as much as it was in hedonism

Hedonism is a family of Philosophy, philosophical views that prioritize pleasure. Psychological hedonism is the theory that all human behavior is Motivation, motivated by the desire to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. As a form of Psycholo ...

. Rochester's venality led to an early death, and he was later frequently invoked as the exemplar of a Restoration rake.

Aphra Behn modelled the rake Willmore in her play ''The Rover'' on Rochester;Willmore may have also been based on Behn's lover John Hoyle.

Aphra Behn modelled the rake Willmore in her play ''The Rover'' on Rochester;Willmore may have also been based on Behn's lover John Hoyle.Behn, Mrs Afra

in ''The Oxford Companion to English Literature'' (2000). Ed. Margaret Drabble. Oxford Reference Online (subscription required), Oxford University Press. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. and while she was best known publicly for her drama (in the 1670s, only Dryden's plays were staged more often than hers), Behn wrote a great deal of poetry that would be the basis of her later reputation. Edward Bysshe would include numerous quotations from her verse in his ''Art of English Poetry'' (1702). While her poetry was occasionally sexually frank, it was never as graphic or intentionally lurid and titillating as Rochester's. Rather, her poetry was, like the court's ethos, playful and honest about sexual desire. One of the most remarkable aspects of Behn's success in court poetry, however, is that Behn was herself a commoner. She had no more relation to peers than Dryden, and possibly quite a bit less. As a woman, a commoner, and

Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

ish, she is remarkable for her success in moving in the same circles as the King himself. As Janet Todd and others have shown, she was likely a spy for the Royalist side during the Interregnum. She was certainly a spy for Charles II in the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War, began on 4 March 1665, and concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Breda (1667), Treaty of Breda on 31 July 1667. It was one in a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars, naval wars between Kingdom of England, England and the D ...

, but found her services unrewarded (in fact, she may have spent time in debtor's prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for Natural person, people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, L ...

) and turned to writing to support herself. Her ability to write poetry that stands among the best of the age gives some lie to the notion that the Restoration was an age of female illiteracy and verse composed and read only by peers.

If Behn is a curious exception to the rule of noble verse, Robert Gould breaks that rule altogether. Gould was born of a common family and

If Behn is a curious exception to the rule of noble verse, Robert Gould breaks that rule altogether. Gould was born of a common family and orphan

An orphan is a child whose parents have died, are unknown, or have permanently abandoned them. It can also refer to a child who has lost only one parent, as the Hebrew language, Hebrew translation, for example, is "fatherless". In some languages ...

ed at the age of thirteen. He had no schooling at all and worked as a domestic servant, first as a footman and then, probably, in the pantry

A pantry is a room or cupboard where beverages, food, (sometimes) dishes, household cleaning products, linens or provisions are stored within a home or office. Food and beverage pantries serve in an ancillary capacity to the kitchen.

Etymol ...

. However, he was attached to the Earl of Dorset's household, and Gould somehow learned to read and write, as well as possibly to read and write Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

. In the 1680s and 1690s, Gould's poetry was very popular. He attempted to write odes for money, but his great success came with ''Love Given O'er, or A Satyr Upon ... Woman'' in 1692. It was a partial adaptation of a satire by Juvenal, but with an immense amount of explicit invective against women. The misogyny

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against Woman, women or girls. It is a form of sexism that can keep women at a lower social status than Man, men, thus maintaining the social roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been wide ...

in this poem is some of the harshest and most visceral in English poetry: the poem sold out all editions. Gould also wrote a ''Satyr on the Play House'' (reprinted in Montagu Sommers's ''The London Stage'') with detailed descriptions of the actions and actors involved in the Restoration stage. He followed the success of ''Love Given O'er'' with a series of misogynistic poems, all of which have specific, graphic, and witty denunciations of female behaviour. His poetry has "virgin

Virginity is a social construct that denotes the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. As it is not an objective term with an operational definition, social definitions of what constitutes virginity, or the lack thereof ...

" brides who, upon their wedding nights, have "the straight gate so wide/ It's been leapt by all mankind," noblewomen who have money but prefer to pay the coachman with oral sex

Oral sex, sometimes referred to as oral intercourse, is sexual activity involving the stimulation of the genitalia of a person by another person using the mouth (including the lips, tongue, or teeth). Cunnilingus is oral sex performed on the vu ...

, and noblewomen having sex in their coaches and having the cobblestones heighten their pleasures. Gould's career was brief, but his success was not a novelty of subliterary misogyny. After Dryden's conversion to Roman Catholicism, Gould even engaged in a poison pen battle with the Laureate. His "Jack Squab" (the Laureate getting paid with squab as well as sack and implying that Dryden would sell his soul for a dinner) attacked Dryden's faithlessness viciously, and Dryden and his friends replied. That a footman even ''could'' conduct a verse war is remarkable. That he did so without, apparently, any prompting from his patron is astonishing.

Translations and controversialists

Roger L'Estrange (per above) was a significant translator, and he also produced verse translations. Others, such asRichard Blackmore

Sir Richard Blackmore (22 January 1654 – 9 October 1729), England, English poet and physician, is remembered primarily as the object of satire and as an epic poet, but he was also a respected medical doctor and theologian.

Earlier years

He ...

, were admired for their "sentence" (declamation and sentiment) but have not been remembered. Also, Elkannah Settle was, in the Restoration, a lively and promising political satirist, though his reputation has not fared well since his day. After booksellers began hiring authors and sponsoring specific translations, the shops filled quickly with poetry from hirelings. Similarly, as periodical literature

Periodical literature (singularly called a periodical publication or simply a periodical) consists of published works that appear in new releases on a regular schedule (''issues'' or ''numbers'', often numerically divided into annual ''volumes ...

began to assert itself as a political force, a number of now anonymous poets produced topical, specifically occasional verse.

The largest and most important form of ''incunabula'' of the era was satire. There were great dangers in being associated with satire and its publication was generally done anonymously. To begin with, defamation

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

law cast a wide net, and it was difficult for a satirist to avoid prosecution if he were proven to have written a piece that seemed to criticise a noble. More dangerously, wealthy individuals would often respond to satire by having the suspected poet physically attacked by ruffians. The Earl of Rochester hired such thugs to attack John Dryden suspected of having written ''An Essay on Satire''. A consequence of this anonymity is that a great many poems, some of them of merit, are unpublished and largely unknown. Political satires against The Cabal, against Sunderland's government, and, most especially, against James II's rumoured conversion to Roman Catholicism, are uncollected. However, such poetry was a vital part of the vigorous Restoration scene, and it was an age of energetic and voluminous satire.

Prose genres

Prose in the Restoration period is dominated by Christian religious writing, but the Restoration also saw the beginnings of two genres that would dominate later periods:fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying character (arts), individuals, events, or setting (narrative), places that are imagination, imaginary or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent ...

and journalism. Religious writing often strayed into political and economic writing, just as political and economic writing implied or directly addressed religion.

Philosophical writing

The Restoration saw the publication of a number of significant pieces of political and philosophical writing that had been spurred by the actions of the Interregnum. Additionally, the court's adoption of Neo-classicism andempirical

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how t ...

science led to a receptiveness toward significant philosophical works.

Thomas Sprat wrote his '' History of the Royal Society'' in 1667 and set forth, in a single document, the goals of empirical science ever after. He expressed grave suspicions of adjective

An adjective (abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a word that describes or defines a noun or noun phrase. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Traditionally, adjectives are considered one of the main part of speech, parts of ...

s, nebulous terminology, and all language that might be subjective. He praised a spare, clean, and precise vocabulary for science and explanations that are as comprehensible as possible. In Sprat's account, the Royal Society explicitly rejected anything that seemed like scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

. For Sprat, as for a number of the founders of the Royal Society, science was Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

: its reasons and explanations had to be comprehensible to all. There would be no priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

s in science, and anyone could reproduce the experiments and hear their lessons. Similarly, he emphasised the need for conciseness in description, as well as reproducibility of experiments.

William Temple, after he retired from being what today would be called Secretary of State, wrote several bucolic prose works in praise of retirement, contemplation, and direct observation of nature. He also brought the Ancients and Moderns quarrel into English with his ''Reflections on Ancient and Modern Learning''. The debates that followed in the wake of this quarrel would inspire many of the major authors of the first half of the 18th century (most notably Swift and

William Temple, after he retired from being what today would be called Secretary of State, wrote several bucolic prose works in praise of retirement, contemplation, and direct observation of nature. He also brought the Ancients and Moderns quarrel into English with his ''Reflections on Ancient and Modern Learning''. The debates that followed in the wake of this quarrel would inspire many of the major authors of the first half of the 18th century (most notably Swift and Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early ...

).

The Restoration was also the time when John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

wrote many of his philosophical works. Locke's empiricism was an attempt at understanding the basis of human understanding itself and thereby devising a proper manner for making sound decisions. These same scientific methods led Locke to his ''Two Treatises of Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (full title: ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True O ...

'', which later inspired the thinkers in the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. As with his work on understanding, Locke moves from the most basic units of society toward the more elaborate, and, like Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

, he emphasises the plastic nature of the social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

. For an age that had seen absolute monarchy overthrown, democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

attempted, democracy corrupted, and limited monarchy restored; only a flexible basis for government could be satisfying.

Religious writing

The Restoration moderated most of the more strident sectarian writing, but radicalism persisted after the Restoration. Puritan authors such as John Milton were forced to retire from public life or adapt, and thoseDiggers

The Diggers were a group of religious and political dissidents in England, associated with a political ideology and programme resembling what would later be called agrarian socialism.; ; ; Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard (Digger), Will ...

, Fifth Monarchist, Leveller

The Levellers were a political movement active during the English Civil War who were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its populism, as sh ...

, Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

, and Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

authors who had preached against monarchy and who had participated directly in the regicide of Charles I were partially suppressed. Consequently, violent writings were forced underground, and many of those who had served in the Interregnum attenuated their positions in the Restoration.

Fox, and William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer, religious thinker, and influential Quakers, Quaker who founded the Province of Pennsylvania during the British colonization of the Americas, British colonial era. An advocate of democracy and religi ...

, made public vows of pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

and preached a new theology of peace and love. Other Puritans contented themselves with being able to meet freely and act on local parishes. They distanced themselves from the harshest sides of their religion that had led to the abuses of Cromwell's reign. Two religious authors stand out beyond the others in this time: John Bunyan and Izaak Walton.

Bunyan's '' The Pilgrim's Progress'' is an allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

of personal salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

and a guide to the Christian life. Instead of any focus on eschatology

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of Contemporary era, present age, human history, or the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic and non-Abrah ...

or divine retribution, Bunyan instead writes about how the individual saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

can prevail against the temptations of mind and body that threaten damnation. The book is written in a straightforward narrative and shows influence from both drama and biography

A biography, or simply bio, is a detailed description of a person's life. It involves more than just basic facts like education, work, relationships, and death; it portrays a person's experience of these life events. Unlike a profile or curri ...

, and yet it also shows an awareness of the allegorical tradition found in Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; – 13 January 1599 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the House of Tudor, Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is re ...

.

Izaak Walton's ''The Compleat Angler

''The Compleat Angler'' (the spelling is sometimes modernised to ''The Complete Angler'', though this spelling also occurs in first editions) is a book by Izaak Walton, first published in 1653 by John and Richard Marriot, Richard Marriot in Lon ...

'' is similarly introspective. Ostensibly, his book is a guide to fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment (Freshwater ecosystem, freshwater or Marine ecosystem, marine), but may also be caught from Fish stocking, stocked Body of water, ...

, but readers treasured its contents for their descriptions of nature and serenity. There are few analogues to this prose work. On the surface, it appears to be in the tradition of other guide books (several of which appeared in the Restoration, including Charles Cotton's '' The Compleat Gamester'', which is one of the earliest attempts at settling the rules of card game

A card game is any game that uses playing cards as the primary device with which the game is played, whether the cards are of a traditional design or specifically created for the game (proprietary). Countless card games exist, including famil ...

s), but, like ''Pilgrim's Progress'', its main business is guiding the individual.

More court-oriented religious prose included sermon collections and a great literature of debate over the convocation

A convocation (from the Latin ''wikt:convocare, convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Ancient Greek, Greek wikt:ἐκκλησία, ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a specia ...

and issues before the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

. The Act of First Fruits and Fifths, the Test Act, the Act of Uniformity 1662, and others engaged the leading divines of the day. Robert Boyle, notable as a scientist, also wrote his ''Meditations'' on God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

, and this work was immensely popular as devotional literature well beyond the Restoration. (Indeed, it is today perhaps most famous for Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the Dean (Christianity), dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swi ...

's parody of it in '' Meditation Upon a Broomstick''.) Devotional literature in general sold well and attests a wide literacy rate among the English middle classes.

Journalism

During the Restoration period, the most common manner of getting news would have been abroadsheet

A broadsheet is the largest newspaper format and is characterized by long Vertical and horizontal, vertical pages, typically of in height. Other common newspaper formats include the smaller Berliner (format), Berliner and Tabloid (newspaper ...

publication. A single, large sheet of paper might have a written, usually partisan, account of an event. However, the period saw the beginnings of the first professional and periodical (meaning that the publication was regular) journalism

Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree of accuracy. The word, a noun, applies to the journ ...

in England. Journalism develops late, generally around the time of William of Orange's claiming the throne in 1689. Coincidentally or by design, England began to have newspapers just when William came to court from Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

, where there were already newspapers being published.

The early efforts at news sheets and periodicals were spotty. Roger L'Estrange produced both ''The News'' and ''City Mercury'', but neither of them was a sustained effort. Henry Muddiman was the first to succeed in a regular news paper with the ''London Gazette

London is the capital and largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Western Europe, with a population of 14.9 million. London stands on the River Tha ...

''. In 1665, Muddiman produced the ''Oxford Gazette'' as a digest of news of the royal court, which was in Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

to avoid the plague in London. When the court moved back to Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

later in the year, the title ''London Gazette'' was adopted (and is still in use today). Muddiman had begun as a journalist in the Interregnum and had been the official journalist of the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an Parliament of England, English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660, making it the longest-lasting Parliament in English and British history. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened f ...

(in the form of ''The Parliamentary Intelligencer''). Although Muddiman's productions are the first regular news accounts, they are still not the first modern newspaper, as the work was sent in manuscript by post to subscribers and was not a printed sheet for general sale to the public. That had to wait for '' The Athenian Mercury''.

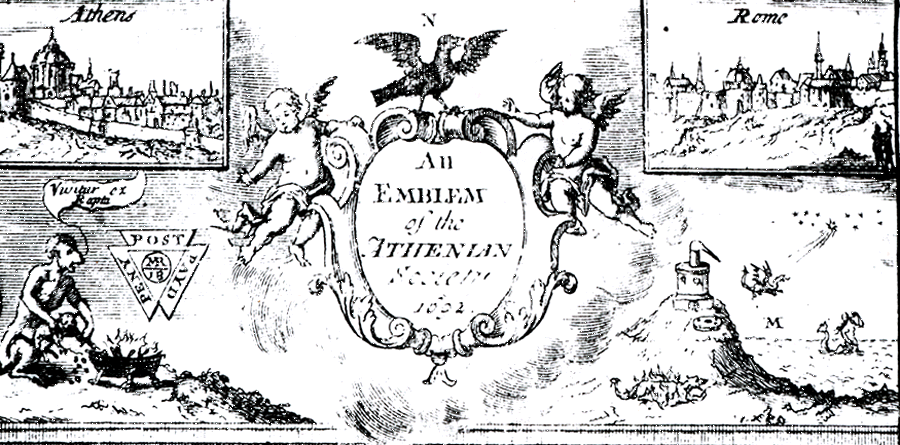

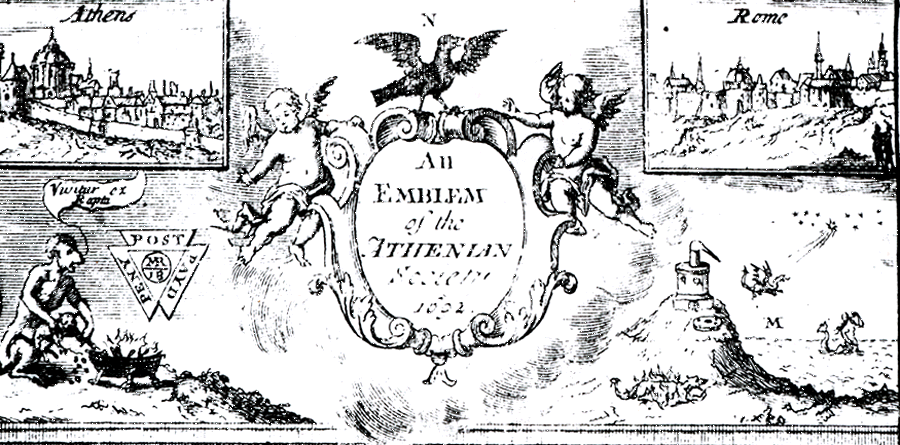

Sporadic essays combined with news had been published throughout the Restoration period, but ''The Athenian Mercury'' was the first regularly published periodical in England. John Dunton and the "Athenian Society" (actually a mathematician, minister, and philosopher paid by Dunton for their work) began publishing in 1691, just after the reign of William III and

Sporadic essays combined with news had been published throughout the Restoration period, but ''The Athenian Mercury'' was the first regularly published periodical in England. John Dunton and the "Athenian Society" (actually a mathematician, minister, and philosopher paid by Dunton for their work) began publishing in 1691, just after the reign of William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 1662 – 28 December 1694) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England, List of Scottish monarchs, Scotland, and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland with her husband, King William III and II, from 1689 until her death in 1694. Sh ...

began. In addition to news reports, ''The Athenian Mercury'' allowed readers to send in questions anonymously and receive a printed answer. The questions mainly dealt with love and health, but there were some bizarre and intentionally amusing questions as well (e.g. a question on why a person shivers after urination

Urination is the release of urine from the bladder through the urethra in Placentalia, placental mammals, or through the cloaca in other vertebrates. It is the urinary system's form of excretion. It is also known medically as micturition, v ...

, written in rhyming couplets). The questions section allowed the journal to sell well and to be profitable. Therefore, it ran for six years, produced four books that spun off from the columns, and then received a bound publication as ''The Athenian Oracle''. He also published the first periodical designed for women "The Ladies' Mercury".

''The Athenian Mercury'' set the stage for the later '' Spectator'', ''Gray's Inn Journal'', ''Temple Bar Journal'', and scores of politically oriented journals, such as the original ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. First published in 1791, it is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.

In 1993 it was acquired by Guardian Media Group Limited, and operated as a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' ...

'', ''The Freeholder'', ''Mist's Journal'', and many others. Also, ''The Athenian Mercury'' published poetry from contributors, and it was the first to publish the poetry of Jonathan Swift and Elizabeth Singer Rowe. The trend of newspapers would similarly explode in subsequent years; a number of these later papers had runs of a single day and were composed entirely as a method of planting political attacks (Pope called them "Sons of a day" in '' Dunciad B'').• Later Romantic writers, who valued the idea of originality, also prized the meaning of "revolution" which signified a violent break with the past and often represented their work as offering just such a break with tradition. However, changes to literary forms and content occurred much more gradually than this use of the word "revolution" might suggest.

Fiction

Although it is impossible to satisfactorily date the beginning of thenovel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

in English, long fiction and fictional biographies began to distinguish themselves from other forms in England during the Restoration period. An existing tradition of ''Romance'' fiction in France and Spain was popular in England. Ludovico Ariosto

Ludovico Ariosto (, ; ; 8 September 1474 – 6 July 1533) was an Italian poet. He is best known as the author of the romance epic '' Orlando Furioso'' (1516). The poem, a continuation of Matteo Maria Boiardo's ''Orlando Innamorato'', describ ...

's '' Orlando Furioso'' engendered prose narratives of love, peril, and revenge, and Gauthier de Costes, seigneur de la Calprenède's novels were quite popular during the Interregnum and beyond.

The "Romance" was considered a feminine form, and women were taxed with reading "novels" as a vice. Inasmuch as these novels were largely read in French or in translation from French, they were associated with effeminacy. However, novels slowly divested themselves of the Arthurian and chivalric trappings and came to centre on more ordinary or picaresque figures. One of the most significant figures in the rise of the novel in the Restoration period is Aphra Behn. She was not only the first professional female novelist, but she may also be among the first professional novelists of either sex in England.