Reorganized National Government Of China on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Wang Jingwei regime or the Wang Ching-wei regime is the common name of the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China ( zh , t = 中華民國國民政府 , p = Zhōnghuá Mínguó Guómín Zhèngfǔ ), the government of the

By April 1938, the national conference of the KMT, held in retreat at the temporary capital of Chongqing, appointed Wang as vice-president of the party, reporting only to Chiang Kai-shek himself. Meanwhile, the Japanese advance into Chinese territory as part of the

By April 1938, the national conference of the KMT, held in retreat at the temporary capital of Chongqing, appointed Wang as vice-president of the party, reporting only to Chiang Kai-shek himself. Meanwhile, the Japanese advance into Chinese territory as part of the

In theory, the Reorganized National Government controlled all of China with the exception of

In theory, the Reorganized National Government controlled all of China with the exception of

The administrative structure of the Reorganized National Government included a

The administrative structure of the Reorganized National Government included a

While Wang had been successful in securing from Japan a "basic treaty" recognizing the foundation of his new party in November 1940, the produced document granted the Reorganized Nationalist Government almost no powers whatsoever. This initial treaty precluded any possibility for Wang to act as intermediary with Chiang Kai-shek and his forces in securing a peace agreement in China. Likewise, the regime was afforded no extra administrative powers in occupied China, save those few previously carved out in Shanghai. Indeed, official Japanese correspondence regarded the Nanjing regime as trivially important, and urged any and all token representatives stationed with Wang and his allies to dismiss all diplomatic efforts by the new government which could not directly contribute to a total military victory over Chiang and his forces. Hoping to expand the treaty in such a way as to be useful, Wang formally traveled to Tokyo in June 1941 in order to meet with prime minister

While Wang had been successful in securing from Japan a "basic treaty" recognizing the foundation of his new party in November 1940, the produced document granted the Reorganized Nationalist Government almost no powers whatsoever. This initial treaty precluded any possibility for Wang to act as intermediary with Chiang Kai-shek and his forces in securing a peace agreement in China. Likewise, the regime was afforded no extra administrative powers in occupied China, save those few previously carved out in Shanghai. Indeed, official Japanese correspondence regarded the Nanjing regime as trivially important, and urged any and all token representatives stationed with Wang and his allies to dismiss all diplomatic efforts by the new government which could not directly contribute to a total military victory over Chiang and his forces. Hoping to expand the treaty in such a way as to be useful, Wang formally traveled to Tokyo in June 1941 in order to meet with prime minister

As the Japanese offensive stalled around the Pacific, conditions remained generally consistent under Wang Jingwei's government. The regime continued to represent itself as the legitimate government of China, continued to appeal to Chiang Kai-shek to seek a peace deal, and continued to chafe under the extremely limited sovereignty afforded by the Japanese occupiers. Yet by 1943, Japanese leaders including

As the Japanese offensive stalled around the Pacific, conditions remained generally consistent under Wang Jingwei's government. The regime continued to represent itself as the legitimate government of China, continued to appeal to Chiang Kai-shek to seek a peace deal, and continued to chafe under the extremely limited sovereignty afforded by the Japanese occupiers. Yet by 1943, Japanese leaders including

The Beijing administration (East Yi Anti-Communist Autonomous Administration) was under the commander-in-chief of the

The Beijing administration (East Yi Anti-Communist Autonomous Administration) was under the commander-in-chief of the

During its existence, the Reorganized National Government nominally led a large army that was estimated to have included 300,000 to 500,000 men, along with a smaller navy and air force. Although its land forces possessed limited armor and artillery, they were primarily an infantry force. Military aid from Japan was also very limited despite Japanese promises to assist the Nanjing regime in the "Japan–China Military Affairs Agreement" that they signed. All military matters were the responsibility of the Central Military Commission, but in practice that body was mainly a ceremonial one. In reality, many of the army's commanders operated outside of the direct command of the central government in Nanjing. The majority of its officers were either former

During its existence, the Reorganized National Government nominally led a large army that was estimated to have included 300,000 to 500,000 men, along with a smaller navy and air force. Although its land forces possessed limited armor and artillery, they were primarily an infantry force. Military aid from Japan was also very limited despite Japanese promises to assist the Nanjing regime in the "Japan–China Military Affairs Agreement" that they signed. All military matters were the responsibility of the Central Military Commission, but in practice that body was mainly a ceremonial one. In reality, many of the army's commanders operated outside of the direct command of the central government in Nanjing. The majority of its officers were either former

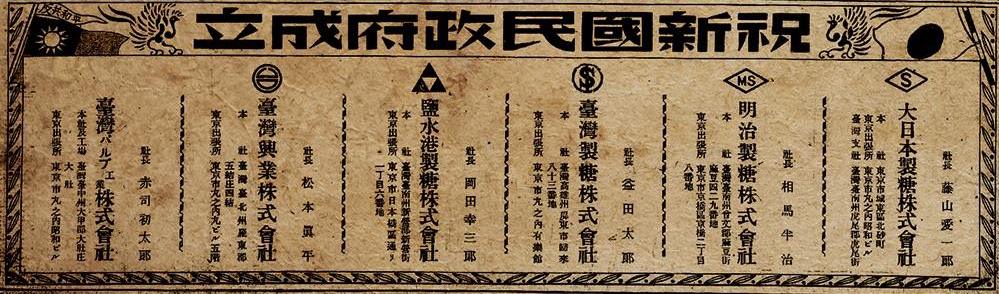

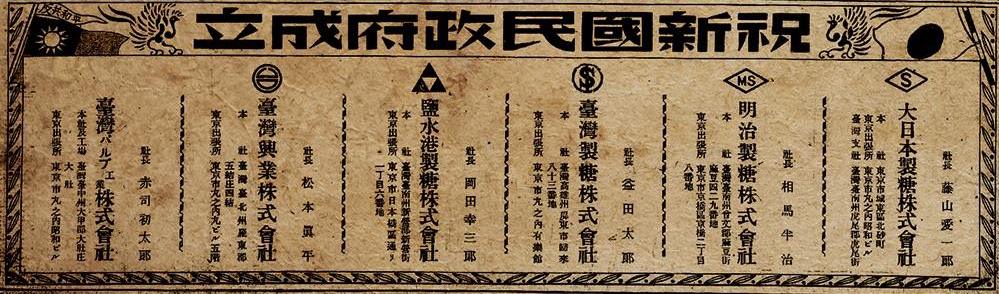

Central China Railway Company Flag, under Japanese Army control

* ttp://www.indiana.edu/~easc/resources/working_paper/noframe_6a_sloga.htm Slogans, Symbols, and Legitimacy: The Case of Wang Jingwei's Nanjing Regimebr>Visual cultures of occupation in wartime China

{{coord, 32, 03, N, 118, 46, E , display=title 1940 establishments in China 1945 disestablishments in China China, Reorganized National Government of China, Reorganized National Government of Military history of China during World War II Second Sino-Japanese War Former countries in Chinese history Axis powers Collaboration with the Axis Powers Client states of the Empire of Japan Former republics States and territories disestablished in 1945 States and territories established in 1940

puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

of the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

in eastern China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

called simply the Republic of China. This should not be confused with the contemporaneously existing National Government of the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

under Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, which was fighting with the Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the Declaration by United Nations, United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during the World War II, Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis ...

against Japan during this period. The country was ruled as a dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

under Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

, a very high-ranking former Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

(KMT) official. The region that it would administer was initially seized by Japan throughout the late 1930s with the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

.

Wang, a rival of Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

and member of the pro-peace faction of the KMT, defected to the Japanese side and formed a collaborationist

Wartime collaboration is cooperation with the enemy against one's country of citizenship in wartime, and in the words of historian Gerhard Hirschfeld, "is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory".

The term ''collaborator'' dates to ...

rebel government in occupied Nanking (Nanjing) (the traditional capital of China) in 1940. The new state claimed the entirety of China during its existence, portraying itself as the legitimate inheritors of the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of ...

and Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

's legacy as opposed to Chiang Kai-shek's government in Chunking (Chongqing), but effectively only Japanese-occupied territory was under its direct control. Its international recognition was limited to other members of the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

, of which it was a signatory. The Reorganized National Government existed until the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and the surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Na ...

in August 1945, at which point the regime was dissolved and many of its leading members were executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

.

The state was formed by combining the previous Reformed Government (1938–1940) and Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

(1937–1940) of the Republic of China, puppet regimes which ruled the central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and northern regions of China that were under Japanese control, respectively. Unlike Wang Jingwei's government, these regimes were not much more than arms of the Japanese military leadership and received no recognition even from Japan itself or its allies. However, after 1940 the former territory of the Provisional Government remained semi-autonomous from Nanjing's control, under the name "North China Political Council

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

". The region of Mengjiang (puppet government in Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

) was under Wang Jingwei's government only nominally. His regime was also hampered by the fact that the powers granted to it by the Japanese were extremely limited, and this was only partly changed with the signing of a new treaty in 1943 which gave it more sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

from Japanese control. The Japanese largely viewed it as not an end in itself but the means to an end, a bridge for negotiations with Chiang Kai-shek, which led them to often treat Wang with indifference.

Names

The regime is informally also known as the ''Nanjing Nationalist Government'' (), the ''Nanjing Regime'', or by its leader ''Wang Jingwei Regime'' (). As the government of the Republic of China and subsequently of the People's Republic of China regard the regime as illegal, it is also commonly known as ''Wang's Puppet Regime'' () or ''Puppet Nationalist Government'' () inGreater China

Greater China is an informal geographical area that shares commercial and cultural ties with the Han Chinese people. The notion of "Greater China" refers to the area that usually encompasses Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan in East ...

. Other names used are the ''Republic of China-Nanjing'', ''China-Nanjing'', or ''New China''.

Background

While Wang Jingwei was widely regarded as a favorite to inheritSun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

's position as leader of the Nationalist Party, based upon his faithful service to the party throughout the 1910s and 20s and based on his unique position as the one who accepted and recorded Dr. Sun's last will and testament, he was rapidly overtaken by Chiang Kai-shek. By the 1930s, Wang Jingwei had taken the position of Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Nationalist Government under Chiang Kai-shek. This put him in control over the deteriorating Sino-Japanese relationship. While Chiang Kai-shek focused his primary attentions against the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

, Wang Jingwei diligently toiled to preserve the peace between China and Japan, repeatedly stressing the need for a period of extended peace in order for China to elevate itself economically and militarily to the levels of its neighbor and the other Great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power i ...

s of the world. Despite his efforts, Wang was unable to find a peaceful solution to prevent the Japanese from commencing an invasion into Chinese territory.

By April 1938, the national conference of the KMT, held in retreat at the temporary capital of Chongqing, appointed Wang as vice-president of the party, reporting only to Chiang Kai-shek himself. Meanwhile, the Japanese advance into Chinese territory as part of the

By April 1938, the national conference of the KMT, held in retreat at the temporary capital of Chongqing, appointed Wang as vice-president of the party, reporting only to Chiang Kai-shek himself. Meanwhile, the Japanese advance into Chinese territory as part of the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

continued unrelentingly. From his new position, Wang urged Chiang Kai-shek to pursue a peace agreement with Japan on the sole condition that the hypothetical deal "did not interfere with the territorial integrity of China". Chiang Kai-shek was adamant, however, that he would countenance no surrender, and that it was his position that, were China to be united completely under his control, the Japanese could readily be repulsed. As a result, Chiang continued to devote his primary attention to eradicating the Communists and ending the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

. On December 18, 1938, Wang Jingwei and several of his closest supporters resigned from their positions and boarded a plane to Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi i ...

in order to seek alternative means of ending the war.

From this new base, Wang began pursuit of a peaceful resolution to the conflict independent of the Nationalist Party in exile. In June 1939, Wang and his supporters began negotiating with the Japanese for the creation of a new Nationalist Government which could end the war despite Chiang's objections. To this end, Wang sought to discredit the Nationalists in Chongqing on the basis that they represented not the republican government envisioned by Dr. Sun, but rather a "one-party dictatorship", and subsequently call together a Central Political Conference back to the capital of Nanjing in order to formally transfer control over the party away from Chiang Kai-shek. These efforts were stymied by Japanese refusal to offer backing for Wang and his new government. Ultimately, Wang Jingwei and his allies would establish their almost entirely powerless new party and government in Nanjing in 1940, in the hope that Tokyo might eventually be willing to negotiate a deal for peace, which, though painful, might allow China to survive.

Wang and his group were also damaged early on by the defection of the diplomat Gao Zongwu

Gao Zongwu ( zh, c=高宗武, w=Kao Tsung-wu; 1905—1994) was a Chinese diplomat in the Republic of China during the Second Sino-Japanese War. He was best known for playing a key role in negotiations between China and Japan from 1937 to 1940 tha ...

, who played a critical role in arranging Wang's defection after two years of negotiations with the Japanese, in January 1940. He had become disillusioned and believed that Japan did not see China as an equal partner, taking with him the documents of the Basic Treaty that Japan had signed with the Wang Jingwei government. He revealed them to the Kuomintang press, becoming a major propaganda coup for Chiang Kai-shek and discrediting Wang's movement in the eyes of the public as mere puppets of the Japanese.

Political boundaries

In theory, the Reorganized National Government controlled all of China with the exception of

In theory, the Reorganized National Government controlled all of China with the exception of Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

, which it recognized as an independent state. In actuality, at the time of its formation, the Reorganized Government controlled only Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an eastern coastal province of the People's Republic of China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with it ...

, Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze Riv ...

, and the north sector of Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Ji ...

, all being Japanese-controlled territories after 1937.

Thereafter, the Reorganized Government's actual borders waxed and waned as the Japanese gained or lost territory during the course of the war. During the December 1941 Japanese offensive the Reorganized Government extended its control over Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangx ...

, Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The p ...

, and parts of Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

provinces. The port of Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

and the cities of Hankou

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers whe ...

and Wuchang

Wuchang forms part of the urban core of and is one of 13 urban districts of the prefecture-level city of Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province, China. It is the oldest of the three cities that merged into modern-day Wuhan, and stood on the ri ...

were also placed under control of the Reformed Government after 1940.

The Japanese-controlled provinces of Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in His ...

and Hebei

Hebei or , (; alternately Hopeh) is a northern province of China. Hebei is China's sixth most populous province, with over 75 million people. Shijiazhuang is the capital city. The province is 96% Han Chinese, 3% Manchu, 0.8% Hui, and ...

were ''de jure'' part of this political entity, though they were ''de facto'' under military administration of the Japanese Northern China Area Army

The was an area army of the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

History

The Japanese North China Area Army was formed on August 21, 1937 under the control of the Imperial General Headquarters. It was transferred to t ...

from its headquarters in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

. Likewise, the Japanese-controlled territories in central China were under military administration of the Japanese Sixth Area Army

The was a field army of the Imperial Japanese Army during both the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

History

The Japanese 6th Area Army was formed on August 25, 1944 under the China Expeditionary Army primarily as a military reserve and ...

from its headquarters in Hankou

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers whe ...

(Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city a ...

). Other Japanese-controlled territories had military administrations directly reporting to the Japanese military headquarters in Nanjing, with the exception of Guangdong and Guangxi which briefly had its headquarters in Canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ente ...

. The central and southern zones of military occupation were eventually linked together after Operation Ichi-Go in 1944, though the Japanese garrison had no effective control over most of this region apart from a narrow strip around the Guangzhou–Hankou railway

The Guangzhou–Hankou or Yuehan railway is a former railroad in China which once connected Guangzhou on the Pearl River in the south with Wuchang on the Yangtze River in the north. At the Yangtze, the railway carriages were ferried to Hankou ...

.

The Reorganized Government's control was mostly limited to:

* Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an eastern coastal province of the People's Republic of China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with it ...

: ; capital: Zhenjiang

Zhenjiang, alternately romanized as Chinkiang, is a prefecture-level city in Jiangsu Province, China. It lies on the southern bank of the Yangtze River near its intersection with the Grand Canal. It is opposite Yangzhou (to its north) a ...

(also included the national capital of Nanking (Nanjing))

* Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze Riv ...

: ; capital: Anqing

Anqing (, also Nganking, formerly Hwaining, now the name of Huaining County) is a prefecture-level city in the southwest of Anhui province, People's Republic of China. Its population was 4,165,284 as of the 2020 census, with 804,493 living in the ...

* Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Ji ...

: ; capital: Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also Chinese postal romanization, romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the prov ...

According to other sources, total extension of territory during 1940 period was 1,264,000 km2.

In 1940 an agreement was signed between the Inner Mongolian puppet state of Mengjiang and the Nanjing regime, incorporating the former into the latter as an autonomous part.

History

Shanghai as de facto capital, 1939–1941

With Nanjing still rebuilding itself after the devastating assault and occupation by the Japanese Imperial Army, the fledgling Reorganized Nationalist Government turned to Shanghai as its primary focal point. With its key role as both an economic and media center for all China, close affiliation to Western Imperial powers even despite the Japanese invasion, and relatively sheltered position from attacks by KMT and Communist forces alike, Shanghai offered both sanctuary and opportunity for Wang and his allies' ambitions. Once in Shanghai, the new regime quickly moved to take control over those publications already supportive of Wang and his peace platform, while also engaging in violent, gang-style attacks against rival news outlets. By November 1940, the Reorganized Nationalist Party had secured enough local support to begin hostile takeovers of both Chinese courts and banks still under nominal control by the KMT in Chongqing or Western powers. Buoyed by this rapid influx of seized collateral, the Reorganized Government under its recently appoint Finance Minister, Zhou Fohai, was able to issue a new currency for circulation. Ultimately however, the already limited economic influence garnered by the new banknotes was further diminished by Japanese efforts to contain the influence of the new regime, at least for a time, to territories firmly under Japanese control like Shanghai and other isolated regions of the Yangtze Valley.Foundation of the Reorganized Government in Nanjing

Legislative Yuan

The Legislative Yuan is the unicameral legislature of the Republic of China (Taiwan) located in Taipei. The Legislative Yuan is composed of 113 members, who are directly elected for 4-year terms by people of the Taiwan Area through a parallel v ...

and an Executive Yuan

The Executive Yuan () is the executive branch of the government of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Its leader is the Premier, who is appointed by the President of the Republic of China, and requires confirmation by the Legislative Yuan.

...

. Both were under the president and head of state Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

. However, actual political power remained with the commander of the Japanese Central China Area Army and Japanese political entities formed by Japanese political advisors.

After obtaining Japanese approval to establish a national government in the summer of 1940, Wang Jingwei ordered the 6th National Congress of the Kuomintang to establish this government in Nanjing. The dedication occurred in the Conference Hall, and both the "blue-sky white-sun red-earth" national flag and the "blue-sky white-sun" Kuomintang flag were unveiled, flanking a large portrait of Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

.

On the day the new government was formed, and just before the session of the "Central Political Conference" began, Wang visited Sun's tomb in Nanjing's Purple Mountain to establish the legitimacy of his power as Sun's successor. Wang had been a high-level official of the Kuomintang government and, as a confidant to Sun, had transcribed Sun's last will, the Zongli's Testament. To discredit the legitimacy of the Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Co ...

government, Wang adopted Sun's flag in the hope that it would establish him as the rightful successor to Sun and bring the government back to Nanjing.

A principal goal of the new regime was to portray itself as the legitimate continuation of the former Nationalist government, despite the Japanese occupation. To this end, the Reorganized government frequently sought to revitalize and expand the former policies of the Nationalist government, often to mixed success.

Efforts to expand Japanese recognition

While Wang had been successful in securing from Japan a "basic treaty" recognizing the foundation of his new party in November 1940, the produced document granted the Reorganized Nationalist Government almost no powers whatsoever. This initial treaty precluded any possibility for Wang to act as intermediary with Chiang Kai-shek and his forces in securing a peace agreement in China. Likewise, the regime was afforded no extra administrative powers in occupied China, save those few previously carved out in Shanghai. Indeed, official Japanese correspondence regarded the Nanjing regime as trivially important, and urged any and all token representatives stationed with Wang and his allies to dismiss all diplomatic efforts by the new government which could not directly contribute to a total military victory over Chiang and his forces. Hoping to expand the treaty in such a way as to be useful, Wang formally traveled to Tokyo in June 1941 in order to meet with prime minister

While Wang had been successful in securing from Japan a "basic treaty" recognizing the foundation of his new party in November 1940, the produced document granted the Reorganized Nationalist Government almost no powers whatsoever. This initial treaty precluded any possibility for Wang to act as intermediary with Chiang Kai-shek and his forces in securing a peace agreement in China. Likewise, the regime was afforded no extra administrative powers in occupied China, save those few previously carved out in Shanghai. Indeed, official Japanese correspondence regarded the Nanjing regime as trivially important, and urged any and all token representatives stationed with Wang and his allies to dismiss all diplomatic efforts by the new government which could not directly contribute to a total military victory over Chiang and his forces. Hoping to expand the treaty in such a way as to be useful, Wang formally traveled to Tokyo in June 1941 in order to meet with prime minister Fumimaro Konoe

Prince was a Japanese politician and prime minister. During his tenure, he presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the breakdown in relations with the United States, which ultimately culminated in Japan's entry into World W ...

and his cabinet to discuss new terms and agreements. Unfortunately for Wang, his visit coincided with the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, a move which further emboldened officials in Tokyo to pursue total victory in China, rather than accept a peace deal. In the end, Konoe eventually agreed to provide a substantial loan to the Nanjing government as well as increased sovereignty; neither of which came to fruition, and indeed, neither of which were even mentioned to military commanders stationed in China. As a slight conciliation, Wang was successful in persuading the Japanese to secure official recognition for the Nanjing Government from the other Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

.

Breakthrough, 1943

As the Japanese offensive stalled around the Pacific, conditions remained generally consistent under Wang Jingwei's government. The regime continued to represent itself as the legitimate government of China, continued to appeal to Chiang Kai-shek to seek a peace deal, and continued to chafe under the extremely limited sovereignty afforded by the Japanese occupiers. Yet by 1943, Japanese leaders including

As the Japanese offensive stalled around the Pacific, conditions remained generally consistent under Wang Jingwei's government. The regime continued to represent itself as the legitimate government of China, continued to appeal to Chiang Kai-shek to seek a peace deal, and continued to chafe under the extremely limited sovereignty afforded by the Japanese occupiers. Yet by 1943, Japanese leaders including Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

, recognizing that the tide of war was turning against them, sought new ways to reinforce the thinly stretched Japanese forces. To this end, Tokyo finally found it expedient to fully recognize Wang Jingwei's government as a full ally, and a replacement Pact of Alliance was drafted for the basic treaty. This new agreement granted the Nanjing government markedly enhanced administrative control over its own territory, as well as increased ability to make limited self-decisions. Despite this windfall, the deal came far too late for the Reorganized government to have sufficient resources to take advantage of its new powers, and Japan was in no condition to offer aid to its new partner.

War on Opium

As a result of general chaos and wartime various profiteering efforts of the conquering Japanese armies, already considerable illegal opium smuggling operations expanded greatly in the Reorganized Nation Government's territory. Indeed, Japanese forces themselves became arguably the largest and most widespread traffickers within the territory under the auspices of semi-official narcotics monopolies. While initially too politically weak to make inroads into the Japanese operations, as the war began to turn against them, the Japanese government sought to incorporate some collaborationist governments more actively into the war effort. To this end in October 1943 the Japanese government signed a treaty with the Reorganized Nationalist Government of China offering them a greater degree of control over their own territory. As a result, Wang Jingwei and his government were able to gain some increased control over the opium monopolies. Negotiations byChen Gongbo

Chen Gongbo (; Japanese: ''Chin Kōhaku''; October 19, 1892 – June 3, 1946) was a Chinese politician, noted for his role as second (and final) President of the collaborationist Wang Jingwei regime during World War II.

Biography

Chen Gongbo ...

were successful in reaching an agreement to cut opium imports from Mongolia in half, as well as an official turnover of state-sponsored monopolies from Japan over to the Reorganized Nationalist Government. Yet, perhaps due to financial concerns, the regime sought only limited reductions in the distribution of opium throughout the remainder of the war.

The Nanjing Government and the northern Chinese areas

Japanese Northern China Area Army

The was an area army of the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

History

The Japanese North China Area Army was formed on August 21, 1937 under the control of the Imperial General Headquarters. It was transferred to t ...

until the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest river system in the world at the estimated length of . Originating in the Bayan Ha ...

area fell inside the sphere of influence of the Japanese Central China Area Army. During this same period the area from middle Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Ji ...

to Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020 ...

was administered by the Japanese North China Area Army. These small, largely independent fiefdoms had local money and local leaders, and frequently squabbled.

Wang Jingwei traveled to Tokyo in 1941 for meetings. In Tokyo the Reorganized National Government Vice President Zhou Fohai commented to the ''Asahi Shimbun

is one of the four largest newspapers in Japan. Founded in 1879, it is also one of the oldest newspapers in Japan and Asia, and is considered a newspaper of record for Japan. Its circulation, which was 4.57 million for its morning edition a ...

'' newspaper that the Japanese establishment was making little progress in the Nanjing area. This quote provoked anger from Kumataro Honda, the Japanese ambassador in Nanjing. Zhou Fohai petitioned for total control of China's central provinces by the Reorganized National Government. In response, Imperial Japanese Army Lt. Gen. Teiichi Suzuki

was a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army, a minister of state, and member of the House of Peers. A close associate of Hideki Tojo, he helped to plan Japan's wartime economy.

Military career

The eldest son of a landowner in Chib ...

was ordered to provide military guidance to the Reorganized National Government, and so became part of the real power that lay behind Wang's rule.

With the permission of the Japanese Army, a monopolistic economic policy was applied, to the benefit of Japanese zaibatsu

is a Japanese term referring to industrial and financial vertically integrated business conglomerates in the Empire of Japan, whose influence and size allowed control over significant parts of the Japanese economy from the Meiji period unt ...

and local representatives. Though these companies were supposedly treated the same as local Chinese companies by the government, the president of the Yuan legislature in Nanjing, Chen Gongbo

Chen Gongbo (; Japanese: ''Chin Kōhaku''; October 19, 1892 – June 3, 1946) was a Chinese politician, noted for his role as second (and final) President of the collaborationist Wang Jingwei regime during World War II.

Biography

Chen Gongbo ...

, complained that this was untrue to the ''Kaizō

''Kaizō'' (改造 ''kaizō'') was a Japanese general-interest magazine that started publication during the Taishō period and printed many articles of socialist content. ''Kaizō'' can be translated into English as "Reorganize", "Restructure" ...

'' Japanese review. The Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China also featured its own embassy in Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

, Japan (as did Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

).

Government and politics

International recognition and foreign relations

The Nanjing Nationalist Government received little international recognition as it was seen as a Japanese puppet state, being recognized only by Japan and the rest of theAxis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. Initially, its main sponsor, Japan, hoped to come to a peace accord with Chiang Kai-shek and held off official diplomatic recognition for the Wang Jingwei regime for eight months after its founding, not establishing formal diplomatic relations with the National Reorganized Government until 30 November 1940. The Sino-Japanese Basic Treaty was signed on 20 November 1940, by which Japan recognised the Nationalist Government, and it also included a Japan–Manchukuo–China joint declaration by which China recognized the Empire of Great Manchuria

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanes ...

and the three countries pledged to create a "New Order in East Asia

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

." The United States and Britain immediately denounced the formation of the government, seeing it as a tool of Japanese imperialism. In July 1941, after negotiations by Foreign Minister Chu Minyi

Chu Minyi; (; Hepburn: ''Cho Mingi''; 1884 – August 23, 1946) was a leading figure in the Chinese republican movement and early Nationalist government, later noted for his role as Minister of Foreign Affairs in the collaborationist Wang Jin ...

, the Nanjing Government was recognized as the government of China by Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. Soon after, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

, and Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

also recognized and established relations with the Wang Jingwei regime as the government of China. China under the Reorganized National Government also became a signatory of the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

on 25 November 1941.

After Japan established diplomatic relations with the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

in 1942, they and their ally Italy pressured Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

to recognize the Nanjing regime and allow a Chinese envoy to be appointed to the Vatican, but he refused to give in to these pressures. Instead the Vatican came to an informal agreement with Japan that their apostolic delegate

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international ...

in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

would pay visits to Catholics in the Nanjing government's territory. The Pope also ignored the suggestion of the aforementioned apostolic delegate, Mario Zanin, who recommended in October 1941 that the Vatican recognize the Wang Jingwei regime as the legitimate government of China. Zanin would remain in the Wang Jingwei regime's territory as apostolic delegate while another bishop in Chongqing was to represent Catholic interests in Chiang Kai-shek's territory. Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

, despite being aligned with the Axis, resisted Japanese pressure and also refused to recognize the Wang Jingwei regime, with French diplomats in China remaining accredited to the government of Chiang Kai-shek.

The Reorganized National Government had its own Foreign Section or Ministry of Foreign Affairs for managing international relations, although it was short on personnel.

On 9 January 1943, the Reorganized National Government signed the "Treaty on Returning Leased Territories and Repealing Extraterritoriality Rights" with Japan, which abolished all foreign concessions within occupied China. Reportedly the date was originally to have been later that month, but was moved to January 9 to be before the United States concluded a similar treaty with Chiang Kai-shek's government. The Nanjing Government then took control of all of the international concessions in Shanghai and its other territories. Later that year Wang Jingwei attended the Greater East Asia Conference

was an international summit held in Tokyo from 5 to 6 November 1943, in which the Empire of Japan hosted leading politicians of various component members of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The event was also referred to as the Toky ...

as the Chinese representative.

The Wang Jingwei government sent Chinese athletes, including the national football team, to compete in the 1940 East Asian Games, which were held in Tokyo for the 2,600th anniversary of the legendary founding of the Japanese Empire by Emperor Jimmu, and were a replacement for the cancelled 1940 Summer Olympics

The 1940 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XII Olympiad, were originally scheduled to be held from September 21 to October 6, 1940, in Tokyo City, Empire of Japan. They were rescheduled for Helsinki, Finland, to be held from ...

.

State ideology

After Japan's pivot towards joining theAxis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

(which included signing the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

), Wang Jingwei's government promoted the idea of pan-Asianism

Satellite photograph of Asia in orthographic projection.

Pan-Asianism (''also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism'') is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian peoples. Various theories and movements of Pan-Asi ...

directed against the West, aimed at establishing a "New Order in East Asia" together with Japan, Manchukuo, and other Asian nations that would expel Western colonial powers from Asia, particularly the "Anglo-Saxons" (the U.S. and Britain) that dominated large parts of Asia. Wang Jingwei used pan-Asianism, basing his views on Sun Yat-sen's advocacy for Asian people to unite against the West in the early 20th century, partly to justify his efforts at working together with Japan. He claimed it was natural for Japan and China to have good relations and cooperation because of their close affinity, describing their conflicts as a temporary aberration in both nation's history. Furthermore, the government believed in the unity of all Asian nations with Japan as their leader as the only way to achieve their goals of removing Western colonial powers from Asia. There was no official description of which Asian peoples were considered to be included in this, but Wang, members of the Propaganda Ministry, and other officials of his regime writing for collaborationist media had different interpretations, at times listing Japan, China, Manchukuo, Thailand, the Philippines, Burma, Nepal, India, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Arabia as potential members of an "East Asian League."

From 1940 onwards, the Wang Jingwei government depicted World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

as a struggle by Asians against the West, more specifically the Anglo-American powers. The Reorganized National Government had a Propaganda Ministry, which exerted control over local media outlets and used them to disseminate pan-Asianist and anti-Western propaganda. British and American diplomats in Shanghai and Nanjing noted by 1940 that the Wang Jingwei-controlled press was publishing anti-Western content. These campaigns were aided by the Japanese authorities in China and also reflected pan-Asian thought as promoted by Japanese thinkers, which intensified after the start of the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vas ...

in December 1941. Pro-regime newspapers and journals published articles which cited instances of racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

towards immigrant Asian communities living in the West and Western colonies in Asia. Chu Minyi

Chu Minyi; (; Hepburn: ''Cho Mingi''; 1884 – August 23, 1946) was a leading figure in the Chinese republican movement and early Nationalist government, later noted for his role as Minister of Foreign Affairs in the collaborationist Wang Jin ...

, the minister of foreign affairs of the Nanjing Government, asserted in an article written shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

that the Sino-Japanese conflict and other wars among Asians were the result of secret manipulation by the Western powers. Lin Baisheng, the minister of propaganda from 1940 to 1944, also made these claims in several of his speeches.

Since Japan was aligned with Germany, Italy, and other European Axis countries, the Nanjing Government's propaganda did not portray the conflict as a war against all white people and focused on the U.S. and Britain in particular. Their newspapers like ''Republican Daily'' praised the German people

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

as a great race for their technological and organizational advancements and glorified the Nazi regime for supposedly transforming Germany into a great power over the past decade. The publications of the Nanjing Government also agreed with the anti-Jewish views held by Nazi Germany, with Wang Jingwei and other officials seeing Jews as dominating the American government and being conspirators with the Anglo-American powers to control the world.

The government also took measures to ban the spread of Anglo-American culture and lifestyle among Chinese people in its territory and promoted traditional Confucian culture. Generally it considered Eastern spiritual culture to be superior to the Western culture of materialism, individualism, and liberalism. Christian missionary schools and missionary activities were banned, the study of English language in schools was reduced, and the usage of English in the postal and customs system was gradually reduced as well. Vice minister of education Tai Yingfu called for a campaign against the Anglo-American nations in education. Zhou Huaren

Zhou Huaren (traditional Chinese: ; simplified Chinese: ; Pinyin:Zhōu Huàrén; Wade–Giles:Chou Hua-jen) (1903 – 1976) was a politician in the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China. He was an important politician during the Wang ...

, vice minister of propaganda, blamed Chinese students that studied in the West for spreading Western values among the population and disparaging traditional Chinese culture. Wang Jingwei blamed communism, anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

, and internationalism (which Wang considered Anglo-American thinking) for making other peoples despise their own culture and embracing the Anglo-American culture. He believed it was necessary to promote Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a Religious Confucianism, religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, ...

to oppose Anglo-American "cultural aggression." At the same time, Zhou Huaren and others also thought that it was necessary to adopt Western scientific advancements while combining them with traditional Eastern culture to develop themselves, as he said Japan did in the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

, seeing that as a model for others to follow.

National defense

National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

personnel or warlord officers from the early Republican era. Thus their reliability and combat capability was questionable, and Wang Jingwei was estimated to only be able to count on the loyalty of about 10% to 15% of his nominal forces. Among the reorganized government's best units were three Capital Guards divisions based in Nanjing, Zhou Fohai's Taxation Police Corps, and the 1st Front Army of Ren Yuandao. Jowett (2004), pp. 65–67

The majority of the government's forces were armed with a mix of captured Nationalist weaponry and a small amount of Japanese equipment, the latter mainly being given to Nanjing's best units. The lack of local military industry for the duration of the war meant that the Nanjing regime had trouble arming its troops. While the army was mainly an infantry force, in 1941 it did receive 18 Type 94 tankette

The Type 94 tankette ( ja, 九四式軽装甲車, Kyūyon-shiki keisōkōsha, literally "94 type light armored car"; also known as TK, an abbreviation of ''Tokushu Keninsha'', literally "special tractor") was a tankette used by the Imperial Japane ...

s for a token armored force, and reportedly they also received 20 armored cars and 24 motorcycles. The main type of artillery in use were medium mortars, but they also possessed 31 field guns (which included Model 1917 mountain gun

Mountain guns are artillery pieces designed for use in mountain warfare and areas where usual wheeled transport is not possible. They are generally capable of being taken apart to make smaller loads for transport by horses, humans, mules, tractor ...

s)—mainly used by the Guards divisions. Oftentimes, the troops were equipped with the German Stahlhelm, which were used in large quantities by the Chinese Nationalist Army. For small arms, there was no standard rifle and a large variety of different weapons were used, which made supplying them with ammunition difficult. The most common rifles in use was the Chinese version of the Mauser 98k and the Hanyang 88

The Type 88, sometimes known as "Hanyang 88" or Hanyang Type 88 () and Hanyang Zao (Which means ''Made in Hanyang''), is a Chinese-made bolt-action rifle, based on the German Gewehr 88. It was adopted by the Qing Dynasty towards the end of the 19 ...

, while other notable weapons included Chinese copies of the Czechoslovakian ZB-26 machine guns.

Along with the great variation in equipment, there was also a disparity in sizes of units. Some "armies" had only a few thousand troops while some "divisions" several thousand. There was a standard divisional structure, but only the elite Guards divisions closer to the capital actually had anything resembling it. In addition to these regular army forces, there were multiple police and local militia, which numbered in the tens of thousands, but were deemed to be completely unreliable by the Japanese. Most of the units located around Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

in northern China remained, in effect, under the authority of the North China Political Council rather than that of the central government. In an attempt to improve the quality of the officer corps, multiple military academies had been opened, including a Central Military Academy in Nanjing and a Naval Academy in Shanghai. In addition there was a military academy in Beijing for the North China Political Council's forces, and a branch of the central academy in Canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ente ...

.

A small navy was established with naval bases at Weihaiwei

Weihai (), formerly called Weihaiwei (), is a prefecture-level city and major seaport in easternmost Shandong province. It borders Yantai to the west and the Yellow Sea to the east, and is the closest Chinese city to South Korea.

Weihai's popul ...

and Qingdao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means " azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

, but it mostly consisted of small patrol boats that were used for coastal and river defense. Reportedly, the captured Nationalist cruisers '' Ning Hai'' and '' Ping Hai'' were handed over to the government by the Japanese, becoming important propaganda tools. However, the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

took them back in 1943 for its own use. In addition there were two regiments of marines, one at Canton and the other at Weihaiwei. By 1944, the navy was under direct command of Ren Yuandao, the naval minister. An Air Force of the Reorganized National Government was established in May 1941 with the opening of the Aviation School and receiving three aircraft, Tachikawa Ki-9

The was an intermediate training aircraft of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force built by Tachikawa Aircraft Company Ltd in the 1930s. It was known to the Allies under the nickname of "Spruce" during World War II.

Design and development

T ...

trainers. In the future the air force received additional Ki-9 and Ki-55 trainers as well as multiple transports. Plans by Wang Jingwei to form a fighter squadron with Nakajima Ki-27s did not come to fruition as the Japanese did not trust the pilots enough to give them combat aircraft. Morale was low and a number of defections took place. The only two offensive aircraft they did possess were Tupolev SB bombers which were flown by defecting Nationalist crews.

The Reorganized National Government's army was primarily tasked with garrison and police duties in the occupied territories. It also took part in anti- partisan operations against Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

guerrillas, such as in the Hundred Regiments Offensive, or played supporting roles for the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

(IJA). The Nanjing Government undertook a "rural pacification" campaign to eradicate communists from the countryside, arresting and executing many people suspected of being communists, with support from the Japanese.

Japanese methods of recruiting

During the conflicts in central China, the Japanese utilized several methods to recruit Chinese volunteers. Japanese sympathisers including Nanjing's pro-Japanese governor, or major local landowners such as Ni Daolang, were used to recruit local peasants in return for money or food. The Japanese recruited 5,000 volunteers in the Anhui area for the Reorganized National Government Army. Japanese forces and the Reorganized National Government used slogans like "Lay down your guns and take up the plough", "Oppose the Communist Bandits" or "Oppose Corrupt Government and Support the Reformed Government" to dissuade guerrilla attacks and buttress its support. The Japanese used various methods for subjugating the local populace. Initially, fear was used to maintain order, but this approach was altered following appraisals by Japanese military ideologists. In 1939, the Japanese army attempted some populist policies, including: *land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultura ...

by dividing the property of major landowners into small holdings, and allocating them to local peasants;

*providing the Chinese with medical services, including vaccination against cholera, typhus, and varicella, and treatments for other diseases;

*ordering Japanese soldiers not to violate women or laws;

*dropping leaflets from aeroplanes, offering rewards for information (with parlays set up by use of a white surrender flag), the handing over of weapons or other actions beneficial to the Japanese cause. Money and food were often incentives used; and

*dispersal of candy, food and toys to children

Buddhist leaders inside the occupied Chinese territories ("Shao-Kung") were also forced to give public speeches and persuade people of the virtues of a Chinese alliance with Japan, including advocating the breaking-off of all relations with Western powers and ideas.

In 1938, a manifesto was launched in Shanghai, reminding the populace the Japanese alliance's track-record in maintaining "moral supremacy" as compared to the often fractious nature of the previous Republican control, and also accusing Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek of treason for maintaining the Western alliance.

In support of such efforts, in 1941 Wang Jingwei proposed the Qingxiang Plan to be applied along the lower course of the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

. A Qingxiang Plan Committee (''Qingxiang Weiyuan-hui'') was formed with himself as Chairman, and Zhou Fohai and Chen Gongbo (as first and second vice-chairmen respectively). Li Shiqun was made the committee's secretary. Beginning in July 1941, Wang maintained that any areas to which the plan was applied would convert into "model areas of peace, anti-communism

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

, and rebuilders of the country" (''heping fangong jianguo mofanqu''). It was not a success.

Economy

TheNorth China Transportation Company

The North China Transportation Company (華北交通株式会社, Japanese: ''Kahoku Kōtsū kabushiki gaisha'', Chinese: ''Huáběi Jiāotōng Zhūshì Huìshè'') was a transportation company in the territory of the collaborationist Provisional ...

and the Central China Railway

The Central China Railway (Japanese: 華中鉄道株式会社, ''Kachū Tetsudō Kabushiki Kaisha''; Chinese: 華中鐵道股份有限公司, ''Huázhōng Tiědào Gǔfèn Yǒuxiàn Gōngsī'') was a railway company in Japanese-occupied China esta ...

were established by the former Provisional Government and Reformed Government, which had nationalised private railway and bus companies that operated in their territories, and continued to function providing railway and bus services in the Nanjing regime's territory.

Life under the regime

Japanese under the regime had greater access to coveted wartime luxuries, and the Japanese enjoyed things like matches, rice, tea, coffee, cigars, foods, and alcoholic drinks, all of which were scarce in Japan proper, but consumer goods became more scarce after Japan entered World War II. In Japanese-occupied Chinese territories the prices of basic necessities rose substantially as Japan's war effort expanded. In Shanghai in 1941, they increased elevenfold. Daily life was often difficult in the Nanjing Nationalist Government-controlled Republic of China, and grew increasingly so as the war turned against Japan (c. 1943). Local residents resorted to theblack market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the ...

in order to obtain needed items or to influence the ruling establishment. The Kempeitai (Japanese Military Police Corps), Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu (Special Higher Police), collaborationist Chinese police, and Chinese citizens in the service of the Japanese all worked to censor information, monitor any opposition, and torture enemies and dissenters. A "native" secret agency, the '' Tewu'', was created with the aid of Japanese Army "advisors". The Japanese also established prisoner-of-war detention centres, concentration camps, and kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending ...

training centres to indoctrinate pilots.

Since Wang's government held authority only over territories under Japanese military occupation, there was a limited amount that officials loyal to Wang could do to ease the suffering of Chinese under Japanese occupation. Wang himself became a focal point of anti-Japanese resistance. He was demonised and branded as an "arch-traitor" in both KMT and Communist rhetoric. Wang and his government were deeply unpopular with the Chinese populace, who regarded them as traitors to both the Chinese state and Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

identity. Wang's rule was constantly undermined by resistance and sabotage.

The strategy of the local education system was to create a workforce suited for employment in factories and mines, and for manual labor. The Japanese also attempted to introduce their culture and dress to the Chinese. Complaints and agitation called for more meaningful Chinese educational development. Shinto temples and similar cultural centers were built in order to instill Japanese culture and values. These activities came to a halt at the end of the war.

Notable figures

Local administration: *Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

: President and Head of State

*Chen Gongbo

Chen Gongbo (; Japanese: ''Chin Kōhaku''; October 19, 1892 – June 3, 1946) was a Chinese politician, noted for his role as second (and final) President of the collaborationist Wang Jingwei regime during World War II.

Biography

Chen Gongbo ...

: President and Head of State after the death of Wang. Also, President of the Legislative Yuan (1940–1944) and Mayor of the Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

occupied sector.

* Zhou Fohai: Vice President and Finance Minister in the Executive Yuan

*Wen Tsungyao

Wen Tsung-yao () (1876 – November 30, 1947), courtesy name Qinfu (欽甫), was a politician and diplomat in the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China. In the late Qing era, he belonged to the pro-reform group. In the era of the Republic, he pa ...

: Chief of the Judicial Yuan

*Wang Kemin

Wang Kemin (; Wade-Giles: Wang K'o-min, May 4, 1879 – December 25, 1945) was a leading official in the Chinese republican movement and early Beiyang government, later noted for his role as in the collaborationist Provisional Government ...

: Internal Affairs Minister, previously head of the Provisional Government of the Republic of China