Rudders on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a

Rowing oars set aside for steering appeared on large Egyptian vessels long before the time of

Rowing oars set aside for steering appeared on large Egyptian vessels long before the time of

The world's oldest known depiction of a sternpost-mounted rudder can be seen on a pottery model of a Chinese junk dating from the 1st century AD during the

The world's oldest known depiction of a sternpost-mounted rudder can be seen on a pottery model of a Chinese junk dating from the 1st century AD during the  Paul Johnstone and Sean McGrail state that the Chinese invented the "median, vertical and axial" sternpost-mounted rudder, and that such a kind of rudder preceded the pintle-and-gudgeon rudder found in the West by roughly a millennium.

Paul Johnstone and Sean McGrail state that the Chinese invented the "median, vertical and axial" sternpost-mounted rudder, and that such a kind of rudder preceded the pintle-and-gudgeon rudder found in the West by roughly a millennium.

'' Indra of the Ocean'' (Jaladhisakra), which indicates that it was a sea-bound vessel.

While earlier rudders were mounted on the stern by the way of rudderposts or tackles, the iron hinges allowed the rudder to be attached to the entire length of the sternpost in a permanent fashion. However, its full potential could only to be realized after the introduction of the vertical sternpost and the full-rigged ship in the 14th century. From the

While earlier rudders were mounted on the stern by the way of rudderposts or tackles, the iron hinges allowed the rudder to be attached to the entire length of the sternpost in a permanent fashion. However, its full potential could only to be realized after the introduction of the vertical sternpost and the full-rigged ship in the 14th century. From the

/ref> Historian

On an aircraft, a rudder is one of three directional control surfaces, along with the rudder-like

On an aircraft, a rudder is one of three directional control surfaces, along with the rudder-like

Lawrence V. Mott, ''The Development of the Rudder, A.D. 100-1600: A Technological Tale'', Thesis May 1991, Texas A&M University

*Fairbank, John King and Merle Goldman (1992). ''China: A New History; Second Enlarged Edition'' (2006). Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. *Needham, Joseph (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics''. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. {{Authority control Ancient Egyptian technology Ancient inventions Aircraft controls Egyptian inventions Watercraft components Shipbuilding

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship

A ship is a large watercraft, vessel that travels the world's oceans and other Waterway, navigable waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research and fishing. Ships are generally disti ...

, boat

A boat is a watercraft of a large range of types and sizes, but generally smaller than a ship, which is distinguished by its larger size or capacity, its shape, or its ability to carry boats.

Small boats are typically used on inland waterways s ...

, submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

, hovercraft

A hovercraft (: hovercraft), also known as an air-cushion vehicle or ACV, is an amphibious craft capable of travelling over land, water, mud, ice, and various other surfaces.

Hovercraft use blowers to produce a large volume of air below the ...

, airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that may continuously motion, move and Deformation (physics), deform (''flow'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are M ...

medium (usually air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

or water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

). On an airplane

An airplane (American English), or aeroplane (Commonwealth English), informally plane, is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, Propeller (aircraft), propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a vari ...

, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw

Adverse yaw is the natural and undesirable tendency for an aircraft to yaw in the opposite direction of a roll. It is caused by the difference in lift and drag of each wing. The effect can be greatly minimized with ailerons deliberately designed ...

and p-factor

Pfactor, also known as asymmetric blade effect and asymmetric disc effect, is an aerodynamic phenomenon experienced by a moving propeller (aircraft), propeller,) wherein the propeller's center of thrust moves off-center when the aircraft is at ...

and is not the primary control used to turn the airplane. A rudder operates by redirecting the fluid past the hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

or fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

, thus imparting a turning or yawing motion to the craft. In basic form, a rudder is a flat plane or sheet of material attached with hinge

A hinge is a mechanical bearing that connects two solid objects, typically allowing only a limited angle of rotation between them. Two objects connected by an ideal hinge rotate relative to each other about a fixed axis of rotation, with all ...

s to the craft's stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. O ...

, tail, or afterend. Often rudders are shaped to minimize hydrodynamic

In physics, physical chemistry and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids – liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including (the study of air and other gases in moti ...

or aerodynamic drag

In fluid dynamics, drag, sometimes referred to as fluid resistance, is a force acting opposite to the direction of motion of any object moving with respect to a surrounding fluid. This can exist between two fluid layers, two solid surfaces, or b ...

. On simple watercraft

A watercraft or waterborne vessel is any vehicle designed for travel across or through water bodies, such as a boat, ship, hovercraft, submersible or submarine.

Types

Historically, watercraft have been divided into two main categories.

*Raf ...

, a tiller

A tiller or till is a lever used to steer a vehicle. The mechanism is primarily used in watercraft, where it is attached to an outboard motor, rudder post, rudder post or stock to provide leverage in the form of torque for the helmsman to turn ...

—essentially, a stick or pole acting as a lever arm—may be attached to the top of the rudder to allow it to be turned by a helmsman

A helmsman or helm (sometimes driver or steersman) is a person who steering, steers a ship, sailboat, submarine, other type of maritime vessel, airship, or spacecraft. The rank and seniority of the helmsman may vary: on small vessels such as fis ...

. In larger vessels, cables, pushrod

A valvetrain is a mechanical system that controls the operation of the intake and exhaust valves in an internal combustion engine. The intake valves control the flow of air/fuel mixture (or air alone for direct-injected engines) into the combu ...

s, or hydraulics may link rudders to steering wheels. In typical aircraft, the rudder is operated by pedals via mechanical linkages or hydraulics.

History of the rudder

Generally, a rudder is "part of the steering apparatus of a boat or ship that is fastened outside the hull, " denoting all types of oars, paddles, and rudders.rudder.Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 8, 2008, fromEncyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD

An encyclopedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge, either general or special, in a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles or entries that are arranged alphabetically by artic ...

More specifically, the steering gear of ancient vessels can be classified into side-rudders and stern-mounted rudders, depending on their location on the ship. A third term, steering oar

The steering oar or steering board is an over-sized oar or board, to control the direction of a ship or other watercraft prior to the invention of the rudder.

It is normally attached to the starboard side in larger vessels, though in smalle ...

, can denote both types. In a Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

context, side-rudders are more specifically called quarter-rudders as the later term designates more exactly where the rudder was mounted. Stern-mounted rudders are uniformly suspended at the back of the ship in a central position.William F. Edgerton: “Ancient Egyptian Steering Gear”, ''The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures'', Vol. 43, No. 4. (1927), pp. 255-265R. O. Faulkner: ''Egyptian Seagoing Ships'', ''The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology'', Vol. 26. (1941), pp. 3-9

Although some classify a steering oar

The steering oar or steering board is an over-sized oar or board, to control the direction of a ship or other watercraft prior to the invention of the rudder.

It is normally attached to the starboard side in larger vessels, though in smalle ...

as a rudder, others argue that the steering oar used in ancient Egypt and Rome was not a true rudder and define only the stern-mounted rudder used in ancient Han dynasty China as a true rudder. The steering oar can interfere with the handling of the sails (limiting any potential for long ocean-going voyages) while it was fit more for small vessels on narrow, rapid-water transport; the rudder did not disturb the handling of the sails, took less energy to operate by its helmsman

A helmsman or helm (sometimes driver or steersman) is a person who steering, steers a ship, sailboat, submarine, other type of maritime vessel, airship, or spacecraft. The rank and seniority of the helmsman may vary: on small vessels such as fis ...

, was better fit for larger vessels on ocean-going travel, and first appeared in ancient China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

during the 1st century AD.Tom, K.S. (1989). ''Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom''. Honolulu: The Hawaii Chinese History Center of the University of Hawaii Press. . Page 103–104.Adshead, Samuel Adrian Miles. (2000). ''China in World History''. London: MacMillan Press Ltd. New York: St. Martin's Press. . Page 156.Needham, Joseph. (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics''. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Pages 627–628. In regards to the ancient Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n (1550–300 BC) use of the steering oar without a rudder in the Mediterranean, Leo Block (2003) writes:

A single sail tends to turn a vessel in an upwind or downwind direction, and rudder action is required to steer a straight course. A steering oar was used at this time because the rudder had not yet been invented. With a single sail, frequent movement of the steering oar was required to steer a straight course; this slowed down the vessel because a steering oar (or rudder) course correction acts as a brake. The second sail, located forward, could be trimmed to offset the turning tendency of the mainsail and minimize the need for course corrections by the steering oar, which would have substantially improved sail performance.The steering oar or steering board is an oversized oar or board to control the direction of a ship or other watercraft before the invention of the rudder. It is normally attached to the starboard side in larger vessels, though in smaller ones it is rarely if ever, attached.

Steering oar/gear

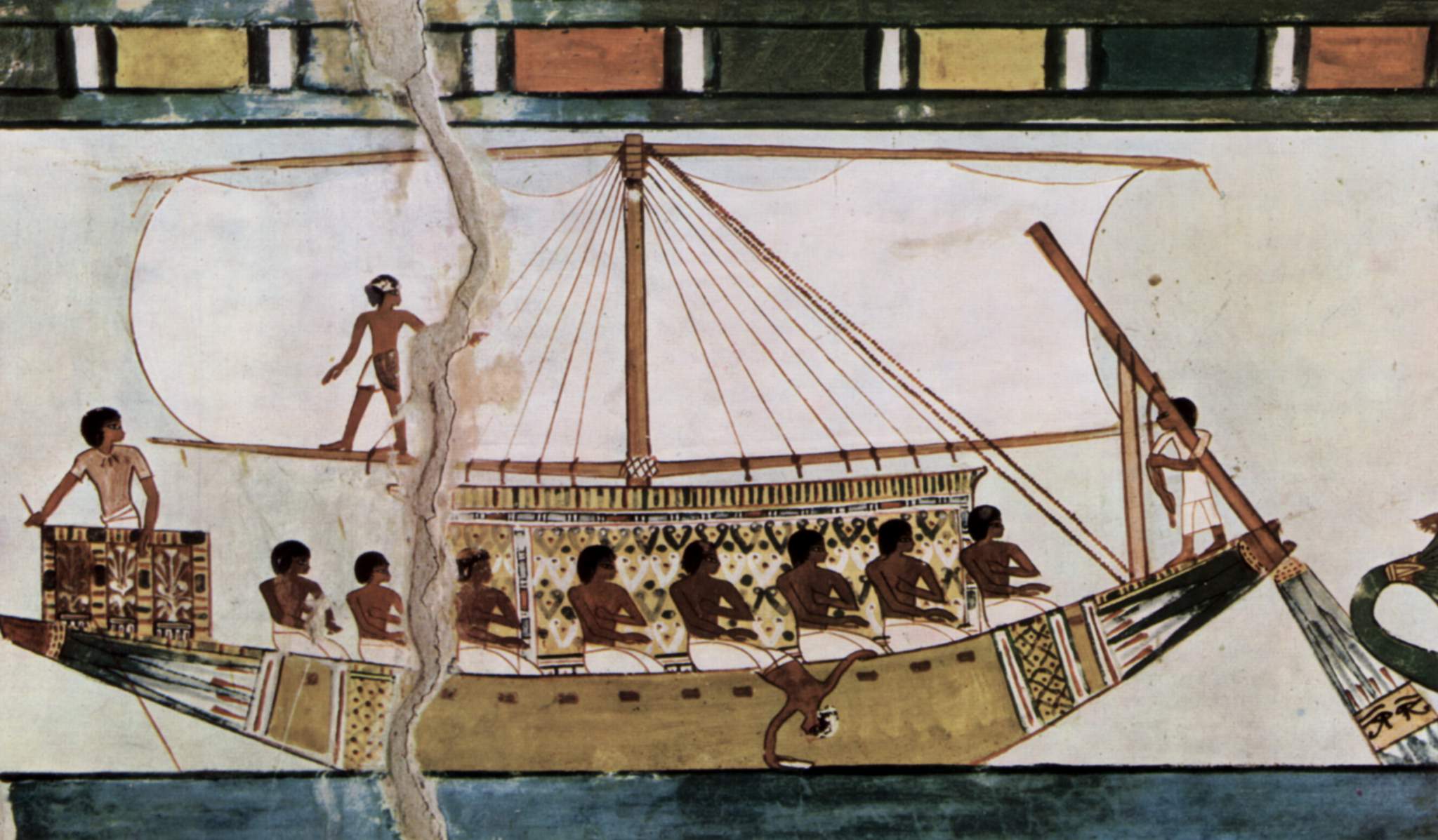

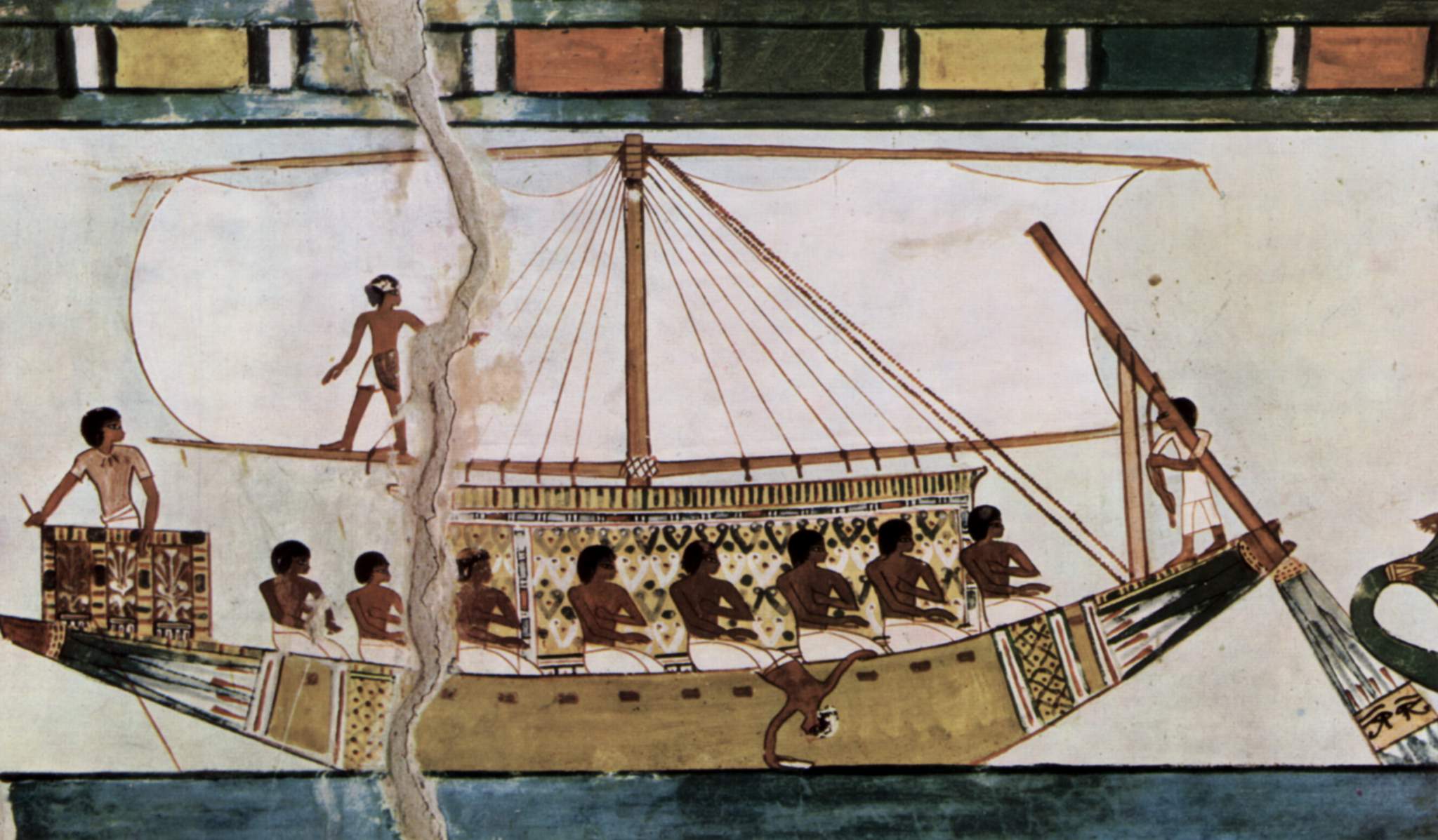

Ancient Egypt

Rowing oars set aside for steering appeared on large Egyptian vessels long before the time of

Rowing oars set aside for steering appeared on large Egyptian vessels long before the time of Menes

Menes ( ; ; , probably pronounced *; and Μήν) was a pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period of ancient Egypt, credited by classical tradition with having united Upper and Lower Egypt, and as the founder of the First Dynasty.

The identity of M ...

(3100 BC).William F. Edgerton: "Ancient Egyptian Steering Gear", ''The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures'', Vol. 43, No. 4. (1927), pp. 255 In the Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning –2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth Dynast ...

(2686–2134 BC) as many as five steering oars are found on each side of passenger boats. The tiller

A tiller or till is a lever used to steer a vehicle. The mechanism is primarily used in watercraft, where it is attached to an outboard motor, rudder post, rudder post or stock to provide leverage in the form of torque for the helmsman to turn ...

, at first a small pin run through the stock of the steering oar, can be traced to the fifth dynasty (2504–2347 BC).William F. Edgerton: "Ancient Egyptian Steering Gear", ''The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures'', Vol. 43, No. 4. (1927), pp. 257 Both the tiller and the introduction of an upright steering post abaft reduced the usual number of necessary steering oars to one each side.William F. Edgerton: "Ancient Egyptian Steering Gear", ''The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures'', Vol. 43, No. 4. (1927), pp. 260 Single steering oars put on the stern can be found in several tomb models of the time, particularly during the Middle Kingdom when tomb reliefs suggest them commonly employed in Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

navigation. The first literary reference appears in the works of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

historian Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

(484–424 BC), who had spent several months in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

: "They make one rudder, and this is thrust through the keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

", probably meaning the crotch at the end of the keel (as depicted in the "Tomb of Menna").

In Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, oars mounted on the side of ships for steering are documented from the 3rd millennium BCE in artwork, wooden models, and even remnants of actual boats.

Ancient Rome

Roman navigation used sexillie quarter steering oars that went in the Mediterranean through a long period of constant refinement and improvement so that by Roman times ancient vessels reached extraordinary sizes.Lawrence V. Mott, The Development of the Rudder, A.D. 100–1600: A Technological Tale, Thesis May 1991, Texas A&M University, p.1 The strength of the steering oar lay in its combination of effectiveness, adaptability and simpleness. Roman quarter steering oar mounting systems survived mostly intact through the medieval period. By the first half of the 1st century AD, steering gear mounted on the stern were also quite common inRoman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

river and harbour craft as proved from relief

Relief is a sculpture, sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''wikt:relief, relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give ...

s and archaeological finds (Zwammerdam

Zwammerdam is a village in the Dutch province of South Holland along Oude Rijn river. It is a part of the municipality of Alphen aan den Rijn, and lies about 6 km southeast of Alphen aan de Rijn. The name derives from a dam built in the Rh ...

, Woerden

Woerden () is a city and a municipality in central Netherlands. Due to its central location between Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht, and the fact that it has rail and road connections to those cities, it is a popular town for commu ...

7). A tomb plaque of Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

ic age shows a harbour tug boat in Ostia with a long stern-mounted oar for better leverage.Lionel Casson: ''Harbour and River Boats of Ancient Rome'', ''The Journal of Roman Studies'', Vol. 55, No. 1/2, Parts 1 and 2 (1965), pp. 31–39 (plate 1) The boat already featured a spritsail

The spritsail is a four-sided, fore-and-aft sail that is supported at its highest points by the mast and a diagonally running spar known as the sprit. The foot of the sail can be stretched by a boom or held loose-footed just by its sheets. A ...

, adding to the mobility of the harbour vessel. Further attested Roman uses of stern-mounted steering oars includes barges under tow, transport ships for wine casks, and diverse other ship types.Lawrence V. Mott, The Development of the Rudder, A.D. 100–1600: A Technological Tale, Thesis May 1991, Texas A&M University, p.84, 95f.Lionel Casson: “Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World”, , S.XXVIII, 336f.; Fig.193Tilmann Bechert: Römisches Germanien zwischen Rhein und Maas. Die Provinz Germania inferior, Hirmer, München 1982, , p.183, 203 (Fig.266) A large river barge found at the mouth of the Rhine near Zwammerdam

Zwammerdam is a village in the Dutch province of South Holland along Oude Rijn river. It is a part of the municipality of Alphen aan den Rijn, and lies about 6 km southeast of Alphen aan de Rijn. The name derives from a dam built in the Rh ...

featured a large steering gear mounted on the stern.M. D. de Weerd: Ships of the Roman Period at Zwammerdam / Nigrum Pullum, Germania Inferior, in: Roman Shipping and Trade: Britain and the Rhine Provinces. (The Council for) British Archaeology, Research Report 24, 1978, 15ff.M. D. de Weerd: Römerzeitliche Transportschiffe und Einbäume aus Nigrum Pullum / Zwammerdam, in: Studien zu den Militärgrenzen Roms II (1977), 187ff. According to new research, the advanced Nemi ships

The Nemi ships were two ships, of different sizes, built under the reign of the Roman emperor Caligula in the 1st century AD on Lake Nemi. Although the purpose of the ships is speculated upon, the larger ship was an elaborate floating palace, w ...

, the palace barges of emperor Caligula

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), also called Gaius and Caligula (), was Roman emperor from AD 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the Roman general Germanicus and Augustus' granddaughter Ag ...

(37–41 AD), may have featured 14-m-long rudders.

Sternpost-mounted rudder

Ancient China

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

, predating their appearance in the West by a thousand years. In China, miniature models of ships that feature steering oars have been dated to the Warring States period

The Warring States period in history of China, Chinese history (221 BC) comprises the final two and a half centuries of the Zhou dynasty (256 BC), which were characterized by frequent warfare, bureaucratic and military reforms, and ...

(c. 475–221 BC). Sternpost-mounted rudders started to appear on Chinese ship models starting in the 1st century AD. However, the Chinese continued to use the steering oar long after they invented the rudder, since the steering oar still had practical use for inland rapid-river travel. One of oldest known depictions of the Chinese stern-mounted rudder (''duò'' ) can be seen on a pottery model of a junk dating from the 1st century AD, during the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

(202 BC220 AD).Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 649-650.Fairbank, 192. It was discovered in Guangzhou

Guangzhou, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Canton or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, southern China. Located on the Pearl River about nor ...

in an archaeological excavation carried out by the Guangdong Provincial Museum and Academia Sinica

Academia Sinica (AS, ; zh, t=中央研究院) is the national academy of the Taiwan, Republic of China. It is headquartered in Nangang District, Taipei, Nangang, Taipei.

Founded in Nanjing, the academy supports research activities in mathemat ...

of Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

in 1958. Within decades, several other Han dynasty ship models featuring rudders were found in archaeological excavations. The first solid written reference to the use of a rudder without a steering oar dates to the 5th century.Johnstone, Paul and Sean McGrail. (1988). ''The Sea-craft of Prehistory''. New York: Routledge. . Page 191.

Chinese rudders are attached to the hull by means of wooden jaws or sockets, while typically larger ones were suspended from above by a rope tackle system so that they could be raised or lowered into the water.Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 362. Also, many junks incorporated "fenestrated rudders" (rudders with holes in them, supposedly allowing for better control). Detailed descriptions of Chinese junks during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

are known from various travellers to China, such as Ibn Battuta

Ibn Battuta (; 24 February 13041368/1369), was a Maghrebi traveller, explorer and scholar. Over a period of 30 years from 1325 to 1354, he visited much of Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the Iberian Peninsula. Near the end of his life, Ibn ...

of Tangier

Tangier ( ; , , ) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The city is the capital city, capital of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region, as well as the Tangier-Assilah Prefecture of Moroc ...

, Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

and Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

of Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

. The later Chinese encyclopedist Song Yingxing

Song Yingxing (Traditional Chinese: 宋應星; Simplified Chinese: 宋应星; Wade Giles: Sung Ying-Hsing; 1587–1666 AD) was a Chinese scientist and encyclopedist who lived during the late Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). He was the author of '' ...

(1587–1666) and the 17th-century European traveler Louis Lecomte wrote of the junk design and its use of the rudder with enthusiasm and admiration.Needham, Volume 4, Par634.

Paul Johnstone and Sean McGrail state that the Chinese invented the "median, vertical and axial" sternpost-mounted rudder, and that such a kind of rudder preceded the pintle-and-gudgeon rudder found in the West by roughly a millennium.

Paul Johnstone and Sean McGrail state that the Chinese invented the "median, vertical and axial" sternpost-mounted rudder, and that such a kind of rudder preceded the pintle-and-gudgeon rudder found in the West by roughly a millennium.

Ancient India

AChandraketugarh

Chandraketugarh, located in the Ganges Delta, are a cluster of villages in the 24 Parganas district of West Bengal, about north-east of Kolkata. The name Chandraketugarh comes from a local legend of a medieval king of this name. This civilizat ...

(West Bengal) seal dated between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD depicts a steering mechanism on a ship named Medieval Near East

Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

ships also used a sternpost-mounted rudder. On their ships "the rudder is controlled by two lines, each attached to a crosspiece mounted on the rudder head perpendicular to the plane of the rudder blade."Lawrence V. Mott, p.93 The earliest evidence comes from the ''Ahsan al-Taqasim fi Marifat al-Aqalim'' ('The Best Divisions for the Classification of Regions') written by al-Muqaddasi

Shams al-Din Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Abi Bakr, commonly known by the '' nisba'' al-Maqdisi or al-Muqaddasī, was a medieval Arab geographer, author of ''The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Regions'' and ''Description of Syri ...

in 985:

: ''The captain from the crow's nest carefully observes the sea. When a rock is espied, he shouts: "Starboard!" or 'Port!" Two youths, posted there, repeat the cry. The helmsman, with two ropes in his hand, when he hears the calls tugs one or the other to the right or left. If great care is not taken, the ship strikes the rocks and is wrecked.''

Medieval Europe

Oars mounted on the side of ships evolved into quarter steering oars, which were used from antiquity until the end of theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

. As the size of ships and the height of the freeboards increased, quarter steering oars became unwieldy and were replaced by the more sturdy rudders with pintle

A pintle is a pin or bolt, usually inserted into a gudgeon, which is used as part of a pivot or hinge. Other applications include pintle and lunette ring for towing, and pintle pins securing casters in furniture.

Use

Pintle/gudgeon sets have ...

and gudgeon

A gudgeon is a socket-like, cylindrical (i.e., ''female'') fitting attached to one component to enable a pivoting or hinging connection to a second component. The second component carries a pintle fitting, the male counterpart to the gudgeon, ...

attachment. While steering oars were found in Europe on a wide range of vessels since Roman times, including light war galleys in Mediterranean, the oldest known depiction of a pintle-and-gudgeon rudder can be found on church carvings of Zedelgem

Zedelgem (; ) is a municipality located in the Belgian province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the villages of Aartrijke, Loppem, Veldegem and Zedelgem proper. On January 1, 2019, Zedelgem had a total population of 22,813. The tota ...

and Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

dating to around 1180.

While earlier rudders were mounted on the stern by the way of rudderposts or tackles, the iron hinges allowed the rudder to be attached to the entire length of the sternpost in a permanent fashion. However, its full potential could only to be realized after the introduction of the vertical sternpost and the full-rigged ship in the 14th century. From the

While earlier rudders were mounted on the stern by the way of rudderposts or tackles, the iron hinges allowed the rudder to be attached to the entire length of the sternpost in a permanent fashion. However, its full potential could only to be realized after the introduction of the vertical sternpost and the full-rigged ship in the 14th century. From the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

onwards, European ships with pintle-and-gudgeon rudders sailed successfully on all seven seas.Lawrence V. Mott, ''The Development of the Rudder, A.D. 100-1600: A Technological Tale'', Thesis May 1991, Texas A&M University, S.118f./ref> Historian

Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, initia ...

holds that the stern-mounted rudder was transferred from China to Europe and the Islamic world during the Middle Ages.

Modern rudders

Conventional rudders have been essentially unchanged sinceIsambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

introduced the balanced rudder

Balanced rudders are used by both ships and aircraft. Both may indicate a portion of the rudder surface ahead of the hinge, placed to lower the control loads needed to turn the rudder. For aircraft the method can also be applied to elevator (air ...

on the SS ''Great Britain'' in 1843 and the steering engine

A steering engine is a power steering device for ships.

History

Prior to the invention of the steering engine, large steam-powered warships with manual steering needed huge crews to turn the rudder rapidly. The Royal Navy once used 78 men hauli ...

in the SS ''Great Eastern'' in 1866. If a vessel requires extra maneuverability at low speeds, the rudder may be supplemented by a manoeuvring thruster

Manoeuvering thrusters (bow thrusters and stern thrusters) are transversal propulsion devices built into or mounted to either the bow or stern (front or back, respectively) of a ship or boat to make it more manoeuvrable. Bow thrusters make doc ...

in the bow, or be replaced entirely by azimuth thruster

An azimuth thruster is a configuration of marine propellers placed in pods that can be rotated to any horizontal angle (azimuth), making a rudder redundant. These give ships better maneuverability than a fixed propeller and rudder system.

Type ...

s.

Boat rudders details

Boat rudders may be either outboard or inboard. Outboard rudders are hung on the stern or transom. Inboard rudders are hung from a keel or skeg and are thus fully submerged beneath the hull, connected to the steering mechanism by a rudder post that comes up through the hull to deck level, often into a cockpit. Inboard keel hung rudders (which are a continuation of the aft trailing edge of the full keel) are traditionally deemed the most damage resistant rudders for off shore sailing. Better performance with faster handling characteristics can be provided by skeg hung rudders on boats with smaller fin keels. Rudder post and mast placement defines the difference between a ketch and a yawl, as these two-masted vessels are similar. Yawls are defined as having the mizzen mast abaft (i.e. "aft of") the rudder post; ketches are defined as having the mizzen mast forward of the rudder post. Small boat rudders that can be steered more or less perpendicular to the hull's longitudinal axis make effective brakes when pushed "hard over." However, terms such as "hard over," "hard to starboard," etc. signify a maximum-rate turn for larger vessels. Transom hung rudders or far aft mounted fin rudders generate greater moment and faster turning than more forward mounted keel hung rudders. Rudders on smaller craft can be operated by means of a tiller that fits into the rudder stock that also forms the fixings to the rudder foil. Craft where the length of the tiller could impede movement of the helm can be split with a rubber universal joint and the part adjoined the tiller termed a tiller extension. Tillers can further be extended by means of adjustable telescopic twist locking extension. There is also the barrel type rudder, where the ship's screw is enclosed and can be swiveled to steer the vessel. Designers claim that this type of rudder on a smaller vessel will answer the helm faster.Rudder control

Large ships (over 10,000 ton gross tonnage) have requirements on rudder turnover time. To comply with this, high torque rudder controls are employed. One commonly used system is the ram type steering gear. It employs four hydraulic rams to rotate the rudder stock (rotation axis), in turn rotating the rudder.Aircraft rudders

On an aircraft, a rudder is one of three directional control surfaces, along with the rudder-like

On an aircraft, a rudder is one of three directional control surfaces, along with the rudder-like elevator

An elevator (American English) or lift (Commonwealth English) is a machine that vertically transports people or freight between levels. They are typically powered by electric motors that drive traction cables and counterweight systems suc ...

(usually attached to the horizontal tail structure, if not a slab elevator) and ailerons

An aileron (French for "little wing" or "fin") is a hinged flight control surface usually forming part of the trailing edge of each wing of a fixed-wing aircraft. Ailerons are used in pairs to control the aircraft in roll (or movement around ...

(attached to the wings), which control pitch and roll, respectively. The rudder is usually attached to the fin

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. F ...

(or vertical stabilizer

A vertical stabilizer or tail fin is the static part of the vertical tail of an aircraft. The term is commonly applied to the assembly of both this fixed surface and one or more movable rudders hinged to it. Their role is to provide control, sta ...

), which allows the pilot to control yaw about the vertical axis, i.e., change the horizontal direction in which the nose is pointing.

Unlike a ship, both aileron

An aileron (French for "little wing" or "fin") is a hinged flight control surface usually forming part of the trailing edge of each wing of a fixed-wing aircraft. Ailerons are used in pairs to control the aircraft in roll (or movement aroun ...

and rudder controls are used together to turn an aircraft, with the ailerons imparting roll and the rudder imparting yaw and also compensating for a phenomenon called adverse yaw

Adverse yaw is the natural and undesirable tendency for an aircraft to yaw in the opposite direction of a roll. It is caused by the difference in lift and drag of each wing. The effect can be greatly minimized with ailerons deliberately designed ...

. A rudder alone will turn a conventional fixed-wing aircraft, but much more slowly than if ailerons are also used in conjunction. Sometimes pilots may intentionally operate the rudder and ailerons in opposite directions in a maneuver called a slip

Slip or The Slip may refer to:

* Slip (clothing), an underdress or underskirt

Music

* The Slip (band), a rock band

* ''Slip'' (album), a 1993 album by the band Quicksand

* ''The Slip'' (album) (2008), a.k.a. Halo 27, the seventh studio al ...

or sideslip. This may be done to overcome crosswinds and keep the fuselage in line with the runway, or to lose altitude by increasing drag, or both.

Another technique for yaw control, used on some tailless aircraft

In aeronautics, a tailless aircraft is a fixed-wing aircraft with no other horizontal aerodynamic surface besides its main wing. It may still have a fuselage, vertical tail fin (vertical stabilizer), and/or vertical rudder.

Theoretical advanta ...

and flying wing

A flying wing is a tailless fixed-wing aircraft that has no definite fuselage, with its crew, payload, fuel, and equipment housed inside the main wing structure. A flying wing may have various small protuberances such as pods, nacelles, blis ...

s, is to add one or more drag-creating surfaces, such as split ailerons, on the outer wing section. Operating one of these surfaces creates drag on the wing, causing the plane to yaw in that direction. These surfaces are often referred to as drag rudders.

Rudders are typically controlled with pedals

A pedal (from the Latin '' pes'' ''pedis'', "foot") is a lever designed to be operated by foot and may refer to:

Computers and other equipment

* Footmouse, a foot-operated computer mouse

* In medical transcription, a pedal is used to control ...

.

See also

* * * * * *Notes

Footnotes

References

Lawrence V. Mott, ''The Development of the Rudder, A.D. 100-1600: A Technological Tale'', Thesis May 1991, Texas A&M University

*Fairbank, John King and Merle Goldman (1992). ''China: A New History; Second Enlarged Edition'' (2006). Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. *Needham, Joseph (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics''. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. {{Authority control Ancient Egyptian technology Ancient inventions Aircraft controls Egyptian inventions Watercraft components Shipbuilding