Robert Watson Watt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Robert Alexander Watson-Watt (13 April 1892 – 5 December 1973) was a Scottish

On 12 February 1935, Watson-Watt sent the secret memo of the proposed system to the

On 12 February 1935, Watson-Watt sent the secret memo of the proposed system to the  By 1937, the first three stations were ready, and the associated system was put to the test. The results were encouraging, and the government immediately commissioned construction of 17 additional stations. This became

By 1937, the first three stations were ready, and the associated system was put to the test. The results were encouraging, and the government immediately commissioned construction of 17 additional stations. This became

Ten years after his knighthood, Watson-Watt was awarded £50,000 by the UK government for his contributions in the development of radar. He established a practice as a consulting engineer. In the 1950s, he moved to

Ten years after his knighthood, Watson-Watt was awarded £50,000 by the UK government for his contributions in the development of radar. He established a practice as a consulting engineer. In the 1950s, he moved to

On 3 September 2014, a statue of Sir Robert Watson-Watt was unveiled in

On 3 September 2014, a statue of Sir Robert Watson-Watt was unveiled in

''The Ditton Park Archive''

*

The Royal Air Force Air Defence Radar Museum at RRH Neatishead, Norfolk

The Watson-Watt Society of Brechin, Angus, Scotland

A comparison of contemporary British and German radar inventions and their use

Radar Development In England

The Robert Watson-Watt Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Watsonwatt, Robert 1892 births 1973 deaths Alumni of the University of Dundee British electrical engineers British electronics engineers Fellows of the Royal Aeronautical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People educated at Brechin High School People from Brechin Presidents of the Royal Meteorological Society Radar pioneers 20th-century Scottish engineers 20th-century Scottish inventors Valdemar Poulsen Gold Medal recipients Academics of the University of Dundee Scientists of the National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom) Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame inductees Fellows of the American Physical Society

radio engineer

Broadcast engineering or radio engineering is the field of electrical engineering, and now to some extent computer engineering and information technology, which deals with radio and television broadcasting. Audio engineering and RF engineering a ...

and pioneer of radio direction finding

Direction finding (DF), radio direction finding (RDF), or radiogoniometry is the use of radio waves to determine the direction to a radio source. The source may be a cooperating radio transmitter or may be an inadvertent source, a natural ...

and radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

technology.

Watt began his career in radio physics

Radiophysics (also modern writing radio physics) is a branch of physics focused on the theoretical and experimental study of certain kinds of radiation, its emission, propagation and interaction with matter.

The term is used in the following maj ...

with a job at the Met Office

The Met Office, until November 2000 officially the Meteorological Office, is the United Kingdom's national weather and climate service. It is an executive agency and trading fund of the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology and ...

, where he began looking for accurate ways to track thunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustics, acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorm ...

s using the radio waves

Radio waves (formerly called Hertzian waves) are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the lowest frequencies and the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies below 300 gigahertz (GHz) and wavelengths ...

given off by lightning

Lightning is a natural phenomenon consisting of electrostatic discharges occurring through the atmosphere between two electrically charged regions. One or both regions are within the atmosphere, with the second region sometimes occurring on ...

. This led to the 1920s development of a system later known as high-frequency direction finding

High-frequency direction finding, usually known by its abbreviation HF/DF or nickname huff-duff, is a type of radio direction finder (RDF) introduced in World War II. High frequency (HF) refers to a radio band that can effectively communicate ove ...

(HFDF or "huff-duff"). Although well publicized at the time, the system's enormous military potential was not developed until the late 1930s. Huff-duff allowed operators to determine the location of an enemy radio transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter (often abbreviated as XMTR or TX in technical documents) is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna with the purpose of signal transmissio ...

in seconds and it became a major part of the network of systems that helped defeat the threat of German U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. It is estimated that huff-duff was used in about a quarter of all attacks on U-boats.

In 1935, Watt was asked to comment on reports of a German death ray

The death ray or death beam is a theoretical particle beam or electromagnetic weapon first theorized around the 1920s and 1930s. Around that time, notable inventors such as Guglielmo Marconi, Nikola Tesla, Harry Grindell Matthews, Edwin R. Scott ...

based on radio. Watt and his assistant Arnold Frederic Wilkins

Arnold Frederic Wilkins OBE (20 February 1907 – 5 August 1985) was a pioneer in developing the use of radar. It was Arnold Wilkins who suggested to his boss, Robert Watson-Watt, that reflected radio waves might be used to detect aircraf ...

quickly determined it was not possible, but Wilkins suggested using radio signals to locate aircraft at long distances. This led to a February 1935 demonstration where signals from a BBC short-wave

Shortwave radio is radio transmission using radio frequencies in the shortwave bands (SW). There is no official definition of the band range, but it always includes all of the high frequency band (HF), which extends from 3 to 30 MHz (appr ...

transmitter were bounced off a Handley Page Heyford

The Handley Page Heyford was a twin-engine biplane bomber designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Handley Page. It holds the distinction of being the last biplane heavy bomber to be operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The ...

aircraft. Watt led the development of a practical version of this device, which entered service in 1938 under the code name Chain Home

Chain Home, or CH for short, was the codename for the ring of coastal early warning radar stations built by the Royal Air Force (RAF) before and during the Second World War to detect and track aircraft. Initially known as RDF, and given the off ...

. This system provided the vital advance information that helped the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

in the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

.

After the success of his invention, Watson Watt was sent to the U.S. in 1941 to advise on air defence after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

. He returned and continued to lead radar development for the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

and Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) was a department of the UK government formed on 1 August 1939 by the Ministry of Supply Act 1939 ( 2 & 3 Geo. 6. c. 38) to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Ministe ...

. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

in 1941, was given a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in 1942 and was awarded the US Medal for Merit

The Medal for Merit was the highest civilian decoration of the United States in the gift of the president. Created during World War II, it was awarded by the president of the United States to civilians who "distinguished themselves by exceptiona ...

in 1946.

Early years

Watson-Watt was born inBrechin

Brechin (; ) is a town and former royal burgh in Angus, Scotland. Traditionally Brechin was described as a city because of its cathedral and its status as the seat of a pre-Scottish Reformation, Reformation Roman Catholic diocese (which contin ...

, Angus, Scotland

Angus (; ) is one of the 32 Local government in Scotland, local government council areas of Scotland, and a Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area. The council area borders Aberdeenshire, Dundee City (council area), Dundee City and Per ...

, on 13 April 1892. He claimed to be a descendant of James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was f ...

, the famous engineer and inventor of the practical steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

, but no evidence of any family relationship has been found. After attending Damacre Primary School and Brechin High School

Brechin High School is a non-denominational secondary school in Brechin, Angus, Scotland.

Admissions

It has approximately 660 students. The school has a relationship with the town's Brechin#Brechin Cathedral, cathedral stretching back to the ear ...

, he was accepted at University College, Dundee (then part of the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

and which became Queen's College, Dundee in 1954 and then the University of Dundee

The University of Dundee is a public research university based in Dundee, Scotland. It was founded as a university college in 1881 with a donation from the prominent Baxter family of textile manufacturers. The institution was, for most of its ...

in 1967). Watson-Watt had a successful time as a student, winning the Carnelley Prize for Chemistry and a class medal for Ordinary Natural Philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

in 1910.

He graduated with a BSc in engineering in 1912, and was offered an assistantship by Professor William Peddie

250px, William Peddie (ca 1910)

William Peddie FRSE LLD (31 May 1861 – 2 June 1946) was a Scottish physicist and applied mathematician, known for his research on colour vision and molecular magnetism.

Life

He was born in Papa Westray in Orkney ...

, the holder of the Chair of Physics at University College, Dundee from 1907 to 1942. It was Peddie who encouraged Watson-Watt to study radio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

, or "wireless telegraphy" as it was then known, and who took him through what was effectively a postgraduate class on the physics of radio frequency oscillators and wave propagation

In physics, mathematics, engineering, and related fields, a wave is a propagating dynamic disturbance (change from equilibrium) of one or more quantities. '' Periodic waves'' oscillate repeatedly about an equilibrium (resting) value at some f ...

. At the start of the Great War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

Watson-Watt was working as an assistant in the college's Engineering Department.

Early experiments

In 1916, Watson-Watt wanted a job with theWar Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

, but nothing obvious was available in communications. Instead, he joined the Meteorological Office

The Met Office, until November 2000 officially the Meteorological Office, is the United Kingdom's national weather and climate service. It is an executive agency and trading fund of the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology and ...

, which was interested in his ideas on the use of radio for the detection of thunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustics, acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorm ...

s. Lightning

Lightning is a natural phenomenon consisting of electrostatic discharges occurring through the atmosphere between two electrically charged regions. One or both regions are within the atmosphere, with the second region sometimes occurring on ...

gives off a radio signal as it ionizes the air, and his goal was to detect this signal to warn pilots of approaching thunderstorms. The signal occurs across a wide range of frequencies and could be easily detected and amplified by naval longwave

In radio, longwave (also spelled long wave or long-wave and commonly abbreviated LW) is the part of the radio spectrum with wavelengths longer than what was originally called the medium-wave (MW) broadcasting band. The term is historic, dati ...

sets. In fact, lightning was a major problem for communications at these common wavelengths.

His early experiments were successful in detecting the signal and he quickly proved to be able to do so at ranges up to 2,500 km (1500 miles). Location was determined by rotating a loop antenna

A loop antenna is a antenna (radio), radio antenna consisting of a loop or coil of wire, tubing, or other electrical conductor, that for transmitting is usually fed by a balanced power source or for receiving feeds a balanced load. Within this p ...

to maximise (or minimise) the signal, thus "pointing" to the storm. The strikes were so fleeting that it was very difficult to turn the antenna in time to positively locate one. Instead, the operator would listen to many strikes and develop a rough average location.

At first, he worked at the Wireless Station of Air Ministry Meteorological Office in Aldershot

Aldershot ( ) is a town in the Rushmoor district, Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme north-east corner of the county, south-west of London. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Farnborough/Aldershot built-up are ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

. In 1924 when the War Department gave notice that they wished to reclaim their Aldershot site, he moved to Ditton Park

Ditton Park, Ditton Manor House or Ditton Park House was the manor house and private feudal demesne of the lord of the Manor of Ditton, Slough, Ditton, and refers today to the rebuilt building and smaller grounds towards the edge of the town of ...

near Slough

Slough () is a town in Berkshire, England, in the Thames Valley, west of central London and north-east of Reading, at the intersection of the M4, M40 and M25 motorways. It is part of the historic county of Buckinghamshire. In 2021, the ...

, Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

. The National Physical Laboratory (NPL) was already using this site and had two main devices that would prove pivotal to his work.

The first was an Adcock antenna

The Adcock antenna is an antenna array consisting of four equidistant vertical elements which can be used to transmit or receive directional radio waves.

The Adcock array was invented and patented by British engineer Frank Adcock and since his A ...

, an arrangement of four masts that allowed the direction of a signal to be detected through phase

Phase or phases may refer to:

Science

*State of matter, or phase, one of the distinct forms in which matter can exist

*Phase (matter), a region of space throughout which all physical properties are essentially uniform

*Phase space, a mathematica ...

differences. Using pairs of these antennas positioned at right angles, one could make a simultaneous measurement of the lightning's direction on two axes. Displaying the fleeting signals was a problem. This was solved by the second device, the WE-224 oscilloscope

An oscilloscope (formerly known as an oscillograph, informally scope or O-scope) is a type of electronic test instrument that graphically displays varying voltages of one or more signals as a function of time. Their main purpose is capturing i ...

, recently acquired from Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, commonly referred to as ''Bell Labs'', is an American industrial research and development company owned by Finnish technology company Nokia. With headquarters located in Murray Hill, New Jersey, Murray Hill, New Jersey, the compa ...

. By feeding the signals from the two antennae into the X and Y channels of the oscilloscope, a single strike caused the appearance of a line on the display, indicating the direction of the strike. The scope's relatively "slow" phosphor only allowed the signal to be read long after the strike had occurred. Watt's new system was being used in 1926 and was the topic of an extensive paper by Watson-Watt and Herd.

The Met and NPL radio teams were amalgamated in 1927 to form the Radio Research Station

The Radio Research Board was formed by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research in 1920. The Radio Research Station (1924 – 31 August 1979) at Ditton Park, near Slough, Berkshire, England was the UK government research laboratory wh ...

with Watson-Watt as director. Continuing research throughout, the teams had become interested in the causes of "static" radio signals and found that much could be explained by distant signals located over the horizon being reflected off the upper atmosphere. This was the first direct indication of the reality of the Heaviside layer, proposed earlier, but at this time largely dismissed by engineers. To determine the altitude of the layer, Watt, Appleton and others developed the ' squegger' to develop a ' time base' display, which would cause the oscilloscope's dot to move smoothly across the display at very high speed. By timing the squegger so that the dot arrived at the far end of the display at the same time as expected signals reflected off the Heaviside layer, the altitude of the layer could be determined. This time-base circuit was key to the development of radar. After a further reorganization in 1933, Watt became Superintendent of the Radio Department of NPL in Teddington

Teddington is an affluent suburb of London in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Historically an Civil parish#ancient parishes, ancient parish in the county of Middlesex and situated close to the border with Surrey, the district became ...

.

RADAR

The air defence problem

During theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Germans had used Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155� ...

s as long-range bombers over Britain and defences had struggled to counter the threat. Since that time, aircraft capabilities had improved considerably and the prospect of widespread aerial bombardment of civilian areas was causing the government anxiety. Heavy bombers were now able to approach at altitudes that anti-aircraft guns of the day were unable to reach. With enemy airfields across the English Channel potentially only 20 minutes' flying-time away, bombers would have dropped their bombs and be returning to base before any intercepting fighters could get to altitude. The only answer seemed to be to have standing patrols of fighters in the air, but with the limited cruising time of a fighter, this would require a huge air force. An alternative solution was urgently needed and, in 1934, the Air Ministry set up a committee, the CSSAD ( Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence), chaired by Sir Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the fir ...

to find ways to improve air defence in the UK.

Rumours that Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

had developed a "death ray

The death ray or death beam is a theoretical particle beam or electromagnetic weapon first theorized around the 1920s and 1930s. Around that time, notable inventors such as Guglielmo Marconi, Nikola Tesla, Harry Grindell Matthews, Edwin R. Scott ...

" that was capable of destroying towns, cities and people using radio waves, were given attention in January 1935 by Harry Wimperis, Director of Scientific Research at the Air Ministry. He asked Watson-Watt about the possibility of building their version of a death-ray, specifically to be used against aircraft. Watson-Watt quickly returned a calculation carried out by his young colleague, Arnold Wilkins, showing that such a device was impossible to construct, and fears of a Nazi version soon vanished. He also mentioned in the same report a suggestion that was originally made to him by Wilkins, who had recently heard of aircraft disturbing shortwave communications, that radio waves might be capable of detecting aircraft, "Meanwhile, attention is being turned to the still difficult, but less unpromising, problem of radio detection and numerical considerations on the method of detection by reflected radio waves will be submitted when required". Wilkins's idea, checked by Watt, was promptly presented by Tizard to the CSSAD on 28 January 1935.

Aircraft detection and location

On 12 February 1935, Watson-Watt sent the secret memo of the proposed system to the

On 12 February 1935, Watson-Watt sent the secret memo of the proposed system to the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force and civil aviation that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the ...

, ''Detection and location of aircraft by radio methods''. Although not as exciting as a death-ray, the concept clearly had potential, but the Air Ministry, before giving funding, asked for a demonstration proving that radio waves could be reflected by an aircraft. This was ready by 26 February and consisted of two receiving antennae located about away from one of the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

's shortwave broadcast stations at Daventry

Daventry ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in the West Northamptonshire unitary authority area of Northamptonshire, England, close to the border with Warwickshire. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 Census, Daventry had a populati ...

. The two antennae were phased such that signals travelling directly from the station cancelled themselves out, but signals arriving from other angles were admitted, thereby deflecting the trace on a CRT

CRT or Crt most commonly refers to:

* Cathode-ray tube, a display

* Critical race theory, an academic framework of analysis

CRT may also refer to:

Law

* Charitable remainder trust, United States

* Civil Resolution Tribunal, Canada

* Columbia ...

indicator (passive radar

Passive radar (also referred to as parasitic radar, passive coherent location, passive surveillance, and passive covert radar) is a class of radar systems that detect and track objects by processing reflections from non-cooperative sources of illu ...

). Such was the secrecy of this test that only three people witnessed it: Watson-Watt, his colleague Arnold Wilkins, and a single member of the committee, A. P. Rowe. The demonstration was a success: on several occasions, the receiver showed a clear return signal from a Handley Page Heyford

The Handley Page Heyford was a twin-engine biplane bomber designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Handley Page. It holds the distinction of being the last biplane heavy bomber to be operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The ...

bomber flown around the site. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (3 August 186714 December 1947), was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was prominent in the political leadership of the United Kingdom between the world wars. He was prime ministe ...

was kept quietly informed of radar progress. On 2 April 1935, Watson-Watt received a patent on a radio device for detecting and locating an aircraft.

In mid-May 1935, Wilkins left the Radio Research Station with a small party, including Edward George Bowen

Edward George "Taffy" Bowen, CBE, FRS (14 January 1911 – 12 August 1991), was a Welsh physicist who made a major contribution to the development of radar. He was also an early radio astronomer, playing a key role in the establishment of ra ...

, to start further research at Orford Ness

Orford Ness is a cuspate foreland shingle spit on the Suffolk coast in Great Britain, linked to the mainland at Aldeburgh and stretching along the coast to Orford and down to North Weir Point, opposite Shingle Street. It is divided from th ...

, an isolated peninsula on the Suffolk coast of the North Sea. By June, they were detecting aircraft at a distance of , which was enough for scientists and engineers to stop all work on competing sound-based detection systems. By the end of the year, the range was up to , at which point, plans were made in December to set up five stations covering the approaches to London.

One of these stations was to be located on the coast near Orford Ness

Orford Ness is a cuspate foreland shingle spit on the Suffolk coast in Great Britain, linked to the mainland at Aldeburgh and stretching along the coast to Orford and down to North Weir Point, opposite Shingle Street. It is divided from th ...

, and Bawdsey Manor

Bawdsey Manor stands at a prominent position at the mouth of the River Deben close to the village of Bawdsey in Suffolk, England, about north-east of London.

Built in 1886, it was enlarged in 1895 as the principal residence of Sir Will ...

was selected to become the main centre for all radar research. To put a radar defence in place as quickly as possible, Watson-Watt and his team created devices using existing components, rather than creating new components for the project, and the team did not take additional time to refine and improve the devices. So long as the prototype radars were in workable condition, they were put into production. They conducted "full scale" tests of a fixed radar radio tower

Radio masts and towers are typically tall structures designed to support antennas for telecommunications and broadcasting, including television. There are two main types: guyed and self-supporting structures. They are among the tallest human-m ...

system, attempting to detect an incoming bomber by radio signals for interception by a fighter. The tests were a complete failure, with the fighter only seeing the bomber after it had passed its target. The problem was not the radar but the flow of information from trackers from the Observer Corps to the fighters, which took many steps and was very slow. Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the fir ...

, Patrick Blackett

Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett, Baron Blackett (18 November 1897 – 13 July 1974) was an English physicist who received the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physics. In 1925, he was the first person to prove that radioactivity could cause the nuclear tr ...

, and Hugh Dowding

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, 1st Baron Dowding, (24 April 1882 – 15 February 1970) was a senior officer in the Royal Air Force. He was Air Officer Commanding RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain and is gene ...

immediately set to work on this problem, designing a 'command and control air defence reporting system' with several layers of reporting that were eventually sent to a single large room for mapping. Observers watching the maps would then tell the fighters what to do via direct communications.

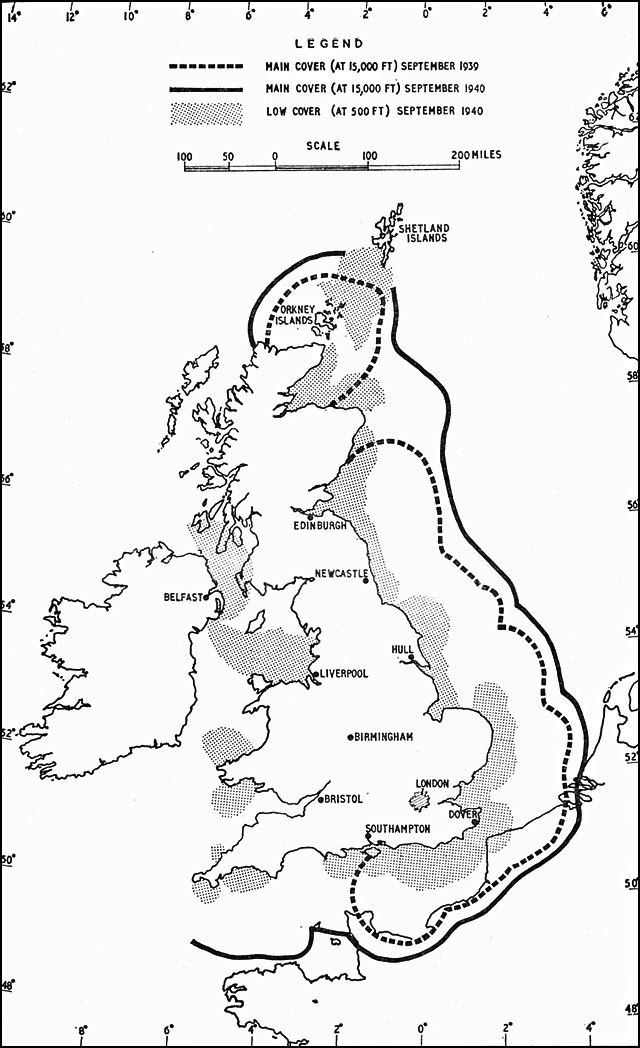

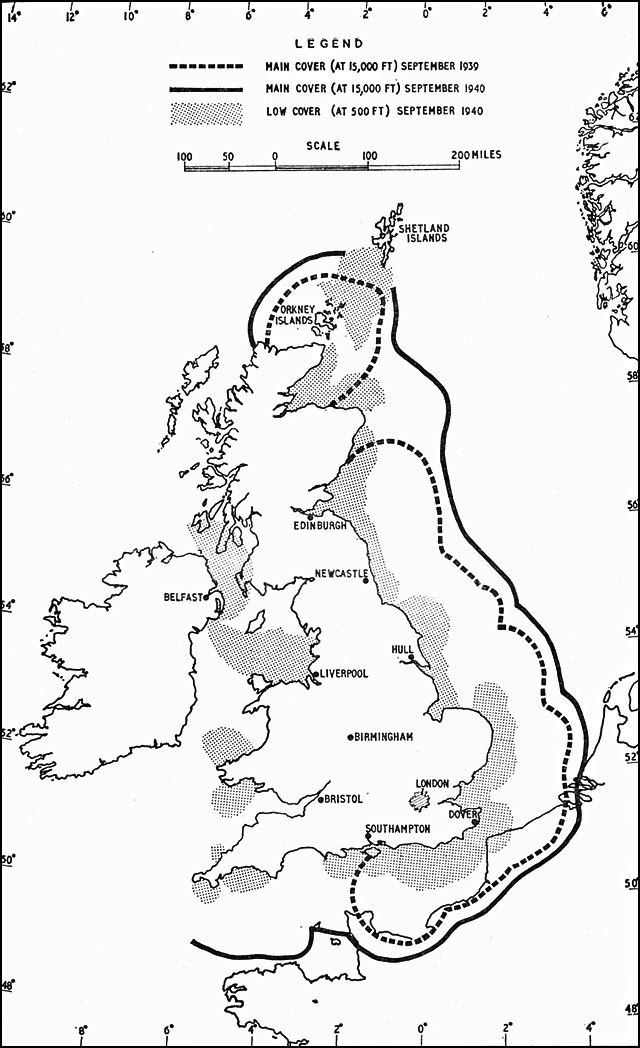

By 1937, the first three stations were ready, and the associated system was put to the test. The results were encouraging, and the government immediately commissioned construction of 17 additional stations. This became

By 1937, the first three stations were ready, and the associated system was put to the test. The results were encouraging, and the government immediately commissioned construction of 17 additional stations. This became Chain Home

Chain Home, or CH for short, was the codename for the ring of coastal early warning radar stations built by the Royal Air Force (RAF) before and during the Second World War to detect and track aircraft. Initially known as RDF, and given the off ...

, the array of fixed radar towers on the east and south coasts of England. By the start of World War II, 19 were ready for the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

, and by the end of the war, over 50 had been built. The Germans were aware of the construction of Chain Home but were not sure of its purpose. They tested their theories with a flight of the Zeppelin LZ 130 but concluded the stations were a new long-range naval communications system.

As early as 1936, it was realized that the ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

'' would turn to night bombing if the day campaign did not go well. Watson-Watt had put another of the staff from the Radio Research Station, Edward Bowen, in charge of developing a radar that could be carried by a fighter. Night-time visual detection of a bomber was good to about 300 m and the existing Chain Home systems simply did not have the accuracy needed to get the fighters that close. Bowen decided that an airborne radar should not exceed 90 kg (200 lb) in weight or 8 ft³ (230 L) in volume and should require no more than 500 watts of power. To reduce the drag of the antennae, the operating wavelength could not be much greater than one metre, difficult for the day's electronics. However, aircraft interception (AI) radar was perfected by 1940 and was instrumental in eventually ending The Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

of 1941. Watson-Watt justified his choice of a non-optimal frequency for his radar, with his oft-quoted "cult of the imperfect", which he stated as "Give them the third-best to go on with; the second-best comes too late; the best never comes".

Civil Service trade union activities

Between 1934 and 1936, Watson-Watt was president of the Institution of Professional Civil Servants, now a part ofProspect

Prospect may refer to:

General

* Prospect (marketing), a marketing term describing a potential customer

* Prospect (sports), any player whose rights are owned by a professional team, but who has yet to play a game for the team

* Prospect (minin ...

, the "union for professionals". The union speculates that at this time he was involved in campaigning for an improvement in pay for Air Ministry staff.

Contribution to Second World War

In his ''English History 1914–1945'', the historianA. J. P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was an English historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his telev ...

paid the highest of praise to Watson-Watt, Sir Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the fir ...

and their associates who developed radar, crediting them with being fundamental to victory in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

In July 1938, Watson-Watt left Bawdsey Manor and took up the post of Director of Communications Development (DCD-RAE). In 1939, Sir George Lee took over the job of DCD and Watson-Watt became Scientific Advisor on Telecommunications (SAT) to the Ministry of Aircraft Production

Ministry may refer to:

Government

* Ministry (collective executive), the complete body of government ministers under the leadership of a prime minister

* Ministry (government department), a department of a government

Religion

* Christian mi ...

, travelling to the US in 1941 to advise them on the severe inadequacies of their air defence, illustrated by the Pearl Harbor attack

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. At the ti ...

. He was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

by George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

in 1942 and received the US Medal for Merit

The Medal for Merit was the highest civilian decoration of the United States in the gift of the president. Created during World War II, it was awarded by the president of the United States to civilians who "distinguished themselves by exceptiona ...

in 1946.

Ten years after his knighthood, Watson-Watt was awarded £50,000 by the UK government for his contributions in the development of radar. He established a practice as a consulting engineer. In the 1950s, he moved to

Ten years after his knighthood, Watson-Watt was awarded £50,000 by the UK government for his contributions in the development of radar. He established a practice as a consulting engineer. In the 1950s, he moved to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

and later he lived in the US, where he published ''Three Steps to Victory'' in 1958. Around 1958, he appeared as a mystery challenger on the American television programme ''To Tell The Truth

''To Tell the Truth'' is an American television panel show. Four celebrity panelists are presented with three contestants (the "team of challengers", each an individual or pair) and must identify which is the "central character" whose unusual ...

''. In 1956, Watson-Watt reportedly was pulled over for speeding in Canada by a radar gun

A radar speed gun, also known as a radar gun, speed gun, or speed trap gun, is a device used to measure the speed of moving objects. It is commonly used by police to check the speed of moving vehicles while conducting Traffic police, traffic enf ...

-toting policeman. His remark was, "Had I known what you were going to do with it I would never have invented it!". He wrote an ironic poem ("A Rough Justice") afterwards,

Pity Sir Robert Watson-Watt, strange target of this radar plot And thus, with others I can mention, the victim of his own invention. His magical all-seeing eye enabled cloud-bound planes to fly but now by some ironic twist it spots the speeding motorist and bites, no doubt with legal wit, the hand that once created it. ...

Honours

* In 1945, Watson-Watt was invited to deliver theRoyal Institution Christmas Lecture

The Royal Institution Christmas Lectures are a series of lectures on a single topic each, which have been held at the Royal Institution in London each year since 1825. The lectures present scientific subjects to a general audience, including you ...

on ''Wireless''.

* In 1949, a Watson-Watt Chair of Electrical Engineering was established at University College, Dundee

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

.

* In 2013, he was one of four inductees to the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame

The Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame honours "those engineers from, or closely associated with, Scotland who have achieved, or deserve to achieve, greatness", as selected by an independent panel representing Scottish engineering institutions, aca ...

.

Legacy

On 3 September 2014, a statue of Sir Robert Watson-Watt was unveiled in

On 3 September 2014, a statue of Sir Robert Watson-Watt was unveiled in Brechin

Brechin (; ) is a town and former royal burgh in Angus, Scotland. Traditionally Brechin was described as a city because of its cathedral and its status as the seat of a pre-Scottish Reformation, Reformation Roman Catholic diocese (which contin ...

by the Princess Royal

Princess Royal is a title customarily (but not automatically) awarded by British monarchs to their eldest daughters. Although purely honorary, it is the highest honour that may be given to a female member of the royal family. There have been ...

. One day later, the BBC Two

BBC Two is a British free-to-air Public service broadcasting in the United Kingdom, public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's second flagship channel, and it covers a wide range of subject matte ...

drama '' Castles in the Sky'', aired with Eddie Izzard

Suzy Eddie Izzard ( ; born Edward John Izzard, 7 February 1962) is a British stand-up comedian, actor and activist. Her comedic style takes the form of what appears to the audience as rambling whimsical monologues and self-referential pantomi ...

in the role of Watson Watt.

A collection of some of the correspondence and papers of Watson-Watt is held by the National Library of Scotland

The National Library of Scotland (NLS; ; ) is one of Scotland's National Collections. It is one of the largest libraries in the United Kingdom. As well as a public programme of exhibitions, events, workshops, and tours, the National Library of ...

. A collection of papers relating to Watson-Watt is also held by Archive Services at the University of Dundee

The University of Dundee is a public research university based in Dundee, Scotland. It was founded as a university college in 1881 with a donation from the prominent Baxter family of textile manufacturers. The institution was, for most of its ...

.

A briefing facility at RAF Boulmer

Royal Air Force Boulmer or more simply RAF Boulmer is a Royal Air Force station near Alnwick in Northumberland, England, and is home to Aerospace Surveillance and Control System (ASACS) Force Command, Control and Reporting Centre (CRC) Boulmer ...

has been named the Watson-Watt auditorium in his honour.

Business and financial life

Watson-Watt had a problematic business and financial life.Family life

Robert Watson-Watt was married three times. He had a daughter with his second wife. Watson-Watt was married on 20 July 1916 in Hammersmith, London to Margaret Robertson (d.1988), the daughter of a draughtsman. In 1952 they divorced and he remarried. His second wife was a Canadian widow, Jean Wilkinson, who later died in 1964. He returned to Scotland in the 1960s, after the closure of his Canadian engineering business. In 1966, at the age of 74, he married Dame Katherine Trefusis Forbes. She was 67 years old at the time and had also played a significant role in theBattle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

as the founding Air Commander of the Women's Auxiliary Air Force

The Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), whose members were referred to as WAAFs (), was the female auxiliary of the British Royal Air Force during the World War II, Second World War. Established in 1939, WAAF numbers exceeded 181,000 at its peak ...

, which supplied the radar-room operatives. The couple lived in London during the winter, and at ''The Observatory'', Trefusis Forbes' summer home, in Pitlochry

Pitlochry (; or ) is a town in the Perth and Kinross council area of Scotland, lying on the River Tummel. It is historically in the county of Perthshire, and has a population of 2,776, according to the 2011 census.Scotland's 2011 census. (n.p. ...

, Perthshire

Perthshire (Scottish English, locally: ; ), officially the County of Perth, is a Shires of Scotland, historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore, Angus and Perth & Kinross, Strathmore ...

, during the warmer months.

Watson-Watt died in 1973, aged 81 in Inverness

Inverness (; ; from the , meaning "Mouth of the River Ness") is a city in the Scottish Highlands, having been granted city status in 2000. It is the administrative centre for The Highland Council and is regarded as the capital of the Highland ...

, two years after his third wife. They are buried together in the churchyard of the Episcopal Church of the Holy Trinity in Pitlochry, Scotland.

See also

*History of radar

The history of radar (where radar stands for ''radio detection and ranging'') started with experiments by Heinrich Hertz in the late 19th century that showed that radio waves were reflected by metallic objects. This possibility was suggested in ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * Lem, Elizabeth''The Ditton Park Archive''

*

The Royal Air Force Air Defence Radar Museum at RRH Neatishead, Norfolk

The Watson-Watt Society of Brechin, Angus, Scotland

External links

A comparison of contemporary British and German radar inventions and their use

Radar Development In England

The Robert Watson-Watt Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Watsonwatt, Robert 1892 births 1973 deaths Alumni of the University of Dundee British electrical engineers British electronics engineers Fellows of the Royal Aeronautical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People educated at Brechin High School People from Brechin Presidents of the Royal Meteorological Society Radar pioneers 20th-century Scottish engineers 20th-century Scottish inventors Valdemar Poulsen Gold Medal recipients Academics of the University of Dundee Scientists of the National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom) Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame inductees Fellows of the American Physical Society