Riftia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Riftia pachyptila'', commonly known as the giant tube worm and less commonly known as the giant beardworm, is a marine

In the middle part, the trunk or third body region, is full of vascularized solid tissue, and includes body wall,

In the middle part, the trunk or third body region, is full of vascularized solid tissue, and includes body wall,

AMP + SO3^2- -> PSreductaseAPS

* APS + PPi -> TP sulfurylaseATP + SO4^2-

The electrons released during the entire sulfide-oxidation process enter in an electron transport chain, yielding a proton gradient that produces ATP (

Giant Tube Worm page at the Smithsonian

Podcast on Giant Tube Worm at the Encyclopedia of Life

* http://www.seasky.org/monsters/sea7a1g.html

* https://web.archive.org/web/20090408022512/http://www.ocean.udel.edu/deepsea/level-2/creature/tube.html {{DEFAULTSORT:Giant Tube Worm Polychaetes Annelids of the Pacific Ocean Animals described in 1981 Chemosynthetic symbiosis Animals living on hydrothermal vents

invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

in the phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

Annelid

The annelids (), also known as the segmented worms, are animals that comprise the phylum Annelida (; ). The phylum contains over 22,000 extant species, including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to vario ...

a (formerly grouped in phylum Pogonophora and Vestimentifera) related to tube worms commonly found in the intertidal and pelagic zone

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean and can be further divided into regions by depth. The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or water column between the sur ...

s. ''R. pachyptila'' lives on the floor of the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

near hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

s. The vents provide a natural ambient temperature in their environment ranging from 2 to 30 °C, and this organism can tolerate extremely high hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

levels. These worms can reach a length of , and their tubular bodies have a diameter of .

Its common name

In biology, a common name of a taxon or organism (also known as a vernacular name, English name, colloquial name, country name, popular name, or farmer's name) is a name that is based on the normal language of everyday life; and is often con ...

"giant tube worm" is, however, also applied to the largest living species of shipworm, '' Kuphus polythalamius'', which despite the name "worm", is a bivalve

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class (biology), class of aquatic animal, aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed b ...

mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

rather than an annelid

The annelids (), also known as the segmented worms, are animals that comprise the phylum Annelida (; ). The phylum contains over 22,000 extant species, including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to vario ...

.

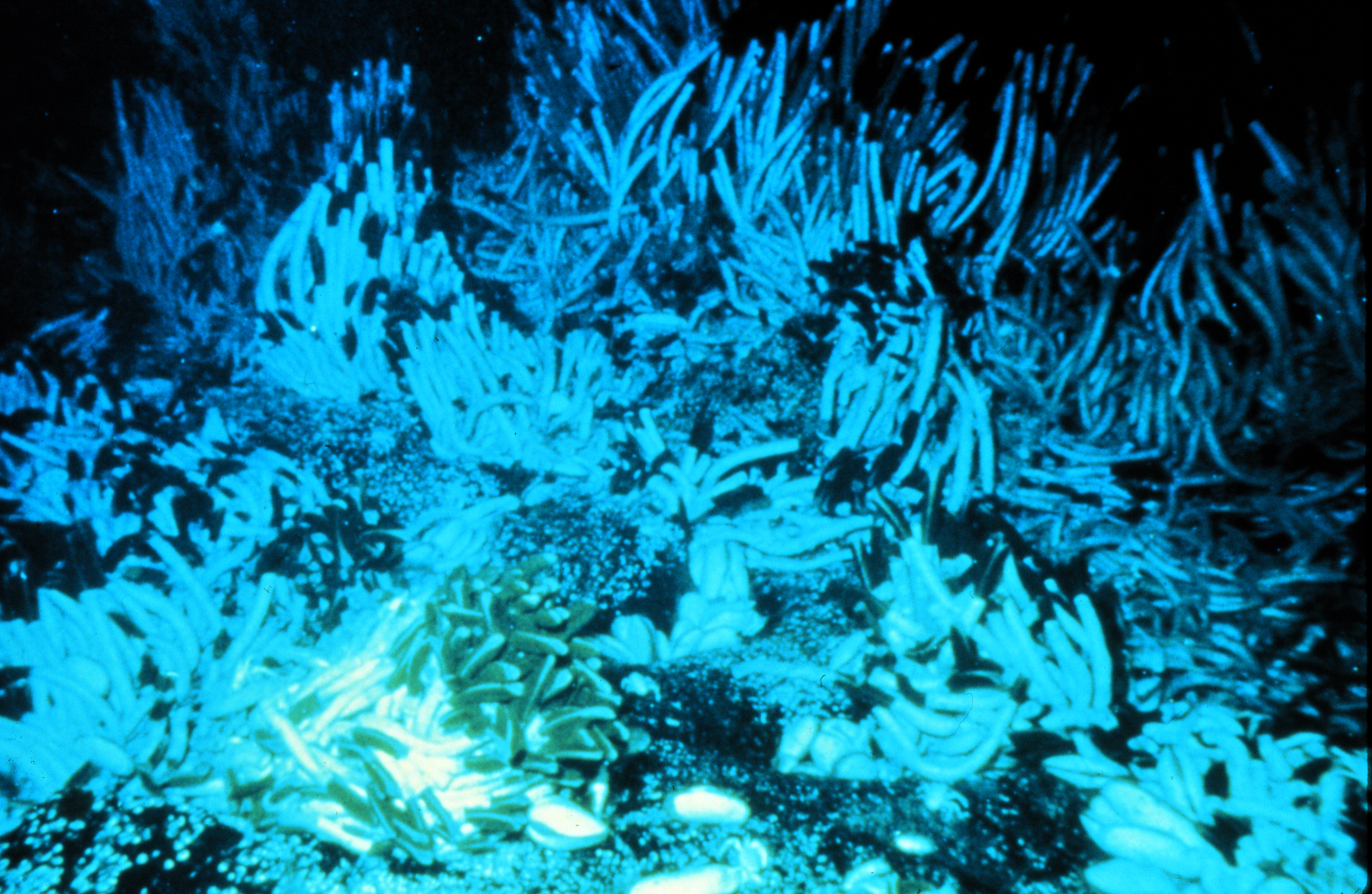

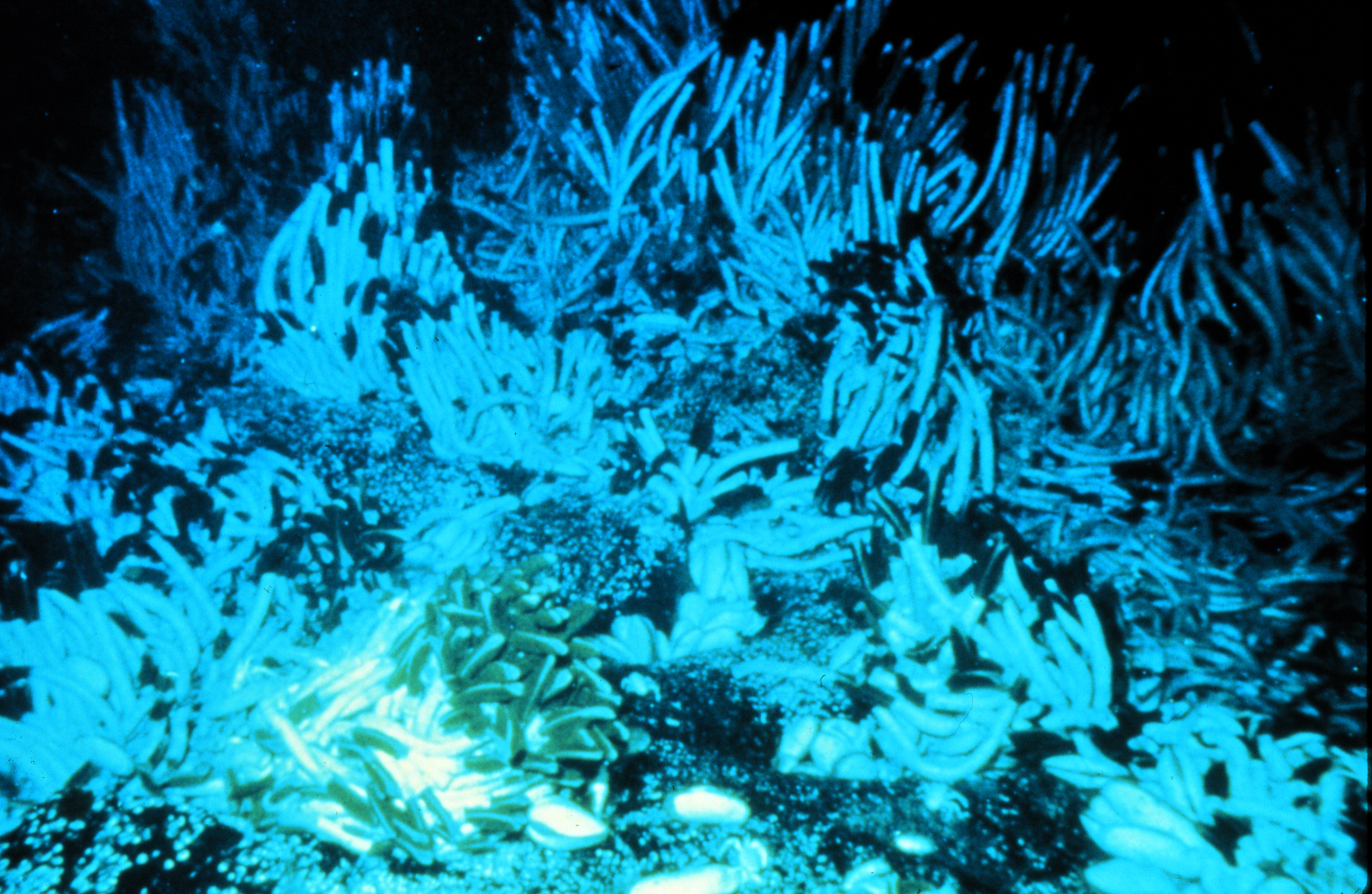

Discovery

''R. pachyptila'' was discovered in 1977 on an expedition of the American bathyscaphe DSV ''Alvin'' to the Galápagos Rift led by geologist Jack Corliss. The discovery was unexpected, as the team was studying hydrothermal vents and no biologists were included in the expedition. Many of the species found living near hydrothermal vents during this expedition had never been seen before. At the time, the presence of thermal springs near the midoceanic ridges was known. Further research uncovered aquatic life in the area, despite the high temperature (around 350–380 °C). Many samples were collected, including bivalves, polychaetes, large crabs, and ''R. pachyptila''. It was the first time that species was observed.Development

''R. pachyptila'' develops from a free-swimming,pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean and can be further divided into regions by depth. The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or water column between the sur ...

, nonsymbiotic trochophore

A trochophore () is a type of free-swimming planktonic marine larva with several bands of cilia.

By moving their cilia rapidly, they make a water eddy to control their movement, and to bring their food closer in order to capture it more easily.

...

larva, which enters juvenile (metatrochophore

A metatrochophore (;) is a type of larva developed from the trochophore larva of a polychaete annelid.

The metatrochophore of a deep-sea hydrothermal vent vestimentiferan has a foregut and a midgut. The foregut cells have several microvilli, basa ...

) development, becoming sessile, and subsequently acquiring symbiotic bacteria. The symbiotic bacteria, on which adult worms depend for sustenance, are not present in the gametes, but are acquired from the environment through the skin in a process akin to an infection. The digestive tract transiently connects from a mouth at the tip of the ventral medial process to a foregut, midgut, hindgut, and anus and was previously thought to have been the method by which the bacteria are introduced into adults. After symbionts are established in the midgut, they undergo substantial remodelling and enlargement to become the trophosome, while the remainder of the digestive tract has not been detected in adult specimens.

Body structure

Isolating the vermiform body from white chitinous tube, a small difference exists from the classic three subdivisions typical of phylum Pogonophora: the prosoma, themesosoma

The mesosoma is the middle part of the body, or tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the metasoma. It bears the legs, and, in the case of winged insects, the wings.

Wasps, bees and a ...

, and the metasoma

The metasoma is the posterior part of the body, or tagma (biology), tagma, of arthropods whose body is composed of three parts, the other two being the prosoma and the mesosoma. In insects, it contains most of the digestive tract, respiratory sy ...

.

The first body region is the vascularized branchial plume, which is bright red due to the presence of hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobin ...

that contain up to 144 globin chains (each presumably including associated heme structures). These tube worm hemoglobins are remarkable for carrying oxygen in the presence of sulfide, without being inhibited by this molecule, as hemoglobins in most other species are. The plume provides essential nutrients to bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

living inside the trophosome. If the animal perceives a threat or is touched, it retracts the plume and the tube is closed due to the obturaculum, a particular operculum that protects and isolates the animal from the external environment.

The second body region is the vestimentum, formed by muscle bands, having a winged shape, and it presents the two genital openings at the end. The heart, extended portion of dorsal vessel, enclose the vestimentum.

In the middle part, the trunk or third body region, is full of vascularized solid tissue, and includes body wall,

In the middle part, the trunk or third body region, is full of vascularized solid tissue, and includes body wall, gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a Heterocrine gland, mixed gland and sex organ that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gon ...

s, and the coelomic cavity. Here is located also the trophosome, spongy tissue where a billion symbiotic, thioautotrophic bacteria and sulfur granules are found. Since the mouth, digestive system, and anus are missing, the survival of ''R. pachyptila'' is dependent on this mutualistic symbiosis. This process, known as chemosynthesis

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrog ...

, was recognized within the trophosome by Colleen Cavanaugh.

The soluble hemoglobins, present in the tentacles, are able to bind O2 and H2S, which are necessary for chemosynthetic bacteria. Due to the capillaries, these compounds are absorbed by bacteria. During the chemosynthesis, the mitochondrial enzyme rhodanase catalyzes the disproportionation reaction of the thiosulfate anion S2O32- to sulfur S and sulfite SO32- . The ''R. pachyptila''’s bloodstream is responsible for absorption of the O2 and nutrients such as carbohydrates.

Nitrate and nitrite are toxic, but are required for biosynthetic processes. The chemosynthetic bacteria within the trophosome convert nitrate to ammonium

Ammonium is a modified form of ammonia that has an extra hydrogen atom. It is a positively charged (cationic) polyatomic ion, molecular ion with the chemical formula or . It is formed by the protonation, addition of a proton (a hydrogen nucleu ...

ions, which then are available for production of amino acids in the bacteria, which are in turn released to the tube worm. To transport nitrate to the bacteria, ''R. pachyptila'' concentrates nitrate in its blood, to a concentration 100 times more concentrated than the surrounding water. The exact mechanism of ''R. pachyptila''’s ability to withstand and concentrate nitrate is still unknown.

In the posterior part, the fourth body region, is the opistosome, which anchors the animal to the tube and is used for the storage of waste from bacterial reactions.

Symbiosis

The discovery of bacterial invertebrate chemoautotrophicsymbiosis

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction, between two organisms of different species. The two organisms, termed symbionts, can fo ...

, particularly in vestimentiferan tubeworms ''R. pachyptila'' and then in vesicomyid clams and mytilid mussels revealed the chemoautotrophic potential of the hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

tube worm. Scientists discovered a remarkable source of nutrition that helps to sustain the conspicuous biomass of invertebrates at vents. Many studies focusing on this type of symbiosis revealed the presence of chemoautotrophic, endosymbiotic, sulfur-oxidizing bacteria mainly in ''R. pachyptila'', which inhabits extreme environments and is adapted to the particular composition of the mixed volcanic and sea waters. This special environment is filled with inorganic metabolites, essentially carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

, oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

, and sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

. In its adult phase, ''R. pachyptila'' lacks a digestive system. To provide its energetic needs, it retains those dissolved inorganic nutrients (sulfide, carbon dioxide, oxygen, nitrogen) into its plume and transports them through a vascular system to the trophosome, which is suspended in paired coelomic cavities and is where the intracellular symbiotic bacteria are found. The trophosome is a soft tissue that runs through almost the whole length of the tube's coelom. It retains a large number of bacteria on the order of 109 bacteria per gram of fresh weight. Bacteria in the trophosome are retained inside bacteriocytes, thereby having no contact with the external environment. Thus, they rely on ''R. pachyptila'' for the assimilation of nutrients needed for the array of metabolic reactions they employ and for the excretion of waste products of carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation, or сarbon assimilation, is the Biological process, process by which living organisms convert Total inorganic carbon, inorganic carbon (particularly carbon dioxide, ) to Organic compound, organic compounds. These o ...

pathways. At the same time, the tube worm depends completely on the microorganisms for the byproducts of their carbon fixation cycles that are needed for its growth.

Initial evidence for a chemoautotrophic symbiosis in ''R. pachyptila'' came from microscopic

The microscopic scale () is the scale of objects and events smaller than those that can easily be seen by the naked eye, requiring a lens or microscope to see them clearly. In physics, the microscopic scale is sometimes regarded as the scale betwe ...

and biochemical

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, ...

analyses showing Gram-negative bacteria packed within a highly vascularized organ in the tubeworm trunk called the trophosome. Additional analyses involving stable isotope

Stable nuclides are Isotope, isotopes of a chemical element whose Nucleon, nucleons are in a configuration that does not permit them the surplus energy required to produce a radioactive emission. The Atomic nucleus, nuclei of such isotopes are no ...

, enzymatic, and physiological

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

characterizations confirmed that the end symbionts of ''R. pachyptila'' oxidize reduced-sulfur compounds to synthesize ATP for use in autotroph

An autotroph is an organism that can convert Abiotic component, abiotic sources of energy into energy stored in organic compounds, which can be used by Heterotroph, other organisms. Autotrophs produce complex organic compounds (such as carbohy ...

ic carbon fixation through the Calvin cycle. The host tubeworm enables the uptake and transport of the substrates required for thioautotrophy, which are HS−, O2, and CO2, receiving back a portion of the organic matter synthesized by the symbiont population. The adult tubeworm, given its inability to feed on particulate matter and its entire dependency on its symbionts for nutrition, the bacterial population is then the primary source of carbon acquisition for the symbiosis. Discovery of bacterial–invertebrate chemoautotrophic symbioses, initially in vestimentiferan tubeworms and then in vesicomyid clams and mytilid mussels, pointed to an even more remarkable source of nutrition sustaining the invertebrates at vents.

Endosymbiosis with chemoautotrophic bacteria

A wide range of bacterial diversity is associated with symbiotic relationships with ''R. pachyptila''. Many bacteria belong to the phylum Campylobacterota (formerly class Epsilonproteobacteria) as supported by the recent discovery in 2016 of the new species ''Sulfurovum riftiae'' belonging to the phylum Campylobacterota, family Helicobacteraceae isolated from ''R. pachyptila'' collected from the East Pacific Rise. Other symbionts belong to the classDelta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet

* D (NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta"), the fourth letter in the Latin alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* Delta Air Lines, a major US carrier ...

-, Alpha

Alpha (uppercase , lowercase ) is the first letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of one. Alpha is derived from the Phoenician letter ''aleph'' , whose name comes from the West Semitic word for ' ...

- and Gammaproteobacteria

''Gammaproteobacteria'' is a class of bacteria in the phylum ''Pseudomonadota'' (synonym ''Proteobacteria''). It contains about 250 genera, which makes it the most genus-rich taxon of the Prokaryotes. Several medically, ecologically, and scienti ...

. The ''Candidatus'' Endoriftia persephone (Gammaproteobacteria) is a facultative ''R. pachyptila'' symbiont and has been shown to be a mixotroph, thereby exploiting both Calvin Benson cycle and reverse TCA cycle (with an unusual ATP citrate lyase) according to availability of carbon resources and whether it is free living in the environment or inside a eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

host. The bacteria apparently prefer a heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

ic lifestyle when carbon sources are available.

Evidence based on 16S rRNA

16S ribosomal RNA (or 16Svedberg, S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome (SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The genes coding for it are referred to as ...

analysis affirms that ''R. pachyptila'' chemoautotrophic bacteria belong to two different clades: Gammaproteobacteria

''Gammaproteobacteria'' is a class of bacteria in the phylum ''Pseudomonadota'' (synonym ''Proteobacteria''). It contains about 250 genera, which makes it the most genus-rich taxon of the Prokaryotes. Several medically, ecologically, and scienti ...

and Campylobacterota (e.g. ''Sulfurovum riftiae'') that get energy from the oxidation

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

of inorganic sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

(H2S, HS−, S2-) to synthesize ATP for carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation, or сarbon assimilation, is the Biological process, process by which living organisms convert Total inorganic carbon, inorganic carbon (particularly carbon dioxide, ) to Organic compound, organic compounds. These o ...

via the Calvin cycle. Unfortunately, most of these bacteria are still uncultivable. Symbiosis works so that ''R. pachyptila'' provides nutrients such as HS−, O2, CO2 to bacteria, and in turn it receives organic matter from them. Thus, because of lack of a digestive system, ''R. pachyptila'' depends entirely on its bacterial symbiont to survive.

In the first step of sulfide-oxidation, reduced sulfur (HS−) passes from the external environment into ''R. pachyptila'' blood, where, together with O2, it is bound by hemoglobin, forming the complex Hb-O2-HS− and then it is transported to the trophosome, where bacterial symbionts reside. Here, HS− is oxidized to elemental sulfur (S0) or to sulfite

Sulfites or sulphites are compounds that contain the sulfite ion (systematic name: sulfate(IV) ion), . The sulfite ion is the conjugate base of bisulfite. Although its acid (sulfurous acid) is elusive, its salts are widely used.

Sulfites are ...

(SO32-).

In the second step, the symbionts make sulfite-oxidation by the "APS pathway", to get ATP. In this biochemical pathway, AMP reacts with sulfite in the presence of the enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

APS reductase, giving APS (adenosine 5'-phosphosulfate). Then, APS reacts with the enzyme ATP sulfurylase in presence of pyrophosphate

In chemistry, pyrophosphates are phosphorus oxyanions that contain two phosphorus atoms in a linkage. A number of pyrophosphate salts exist, such as disodium pyrophosphate () and tetrasodium pyrophosphate (), among others. Often pyrophosphates a ...

(PPi) giving ATP (substrate-level phosphorylation

Substrate-level phosphorylation is a metabolism reaction that results in the production of ATP or GTP supported by the energy released from another high-energy bond that leads to phosphorylation of ADP or GDP to ATP or GTP (note that the rea ...

) and sulfate (SO42-) as end products. In formulas:

* oxidative phosphorylation

Oxidative phosphorylation(UK , US : or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation, is the metabolic pathway in which Cell (biology), cells use enzymes to Redox, oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order ...

). Thus, ATP generated from oxidative phosphorylation and ATP produced by substrate-level phosphorylation become available for CO2 fixation in Calvin cycle, whose presence has been demonstrated by the presence of two key enzymes of this pathway: phosphoribulokinase and RubisCO.

To support this unusual metabolism, ''R. pachyptila'' has to absorb all the substances necessary for both sulfide-oxidation and carbon fixation, that is: HS−, O2 and CO2 and other fundamental bacterial nutrients such as N and P. This means that the tubeworm must be able to access both oxic and anoxic areas.

Oxidation of reduced sulfur compounds requires the presence of oxidized reagents such as oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

and nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . salt (chemistry), Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are solubility, soluble in wa ...

. Hydrothermal vents are characterized by conditions of high hypoxia. In hypoxic conditions, sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

-storing organisms start producing hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

. Therefore, the production of in H2S in anaerobic conditions is common among thiotrophic symbiosis. H2S can be damaging for some physiological

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

processes as it inhibits the activity of cytochrome c oxidase

The enzyme cytochrome c oxidase or Complex IV (was , now reclassified as a translocasEC 7.1.1.9 is a large transmembrane protein complex found in bacteria, archaea, and the mitochondria of eukaryotes.

It is the last enzyme in the Cellular respir ...

, consequentially impairing oxidative phosphorylation

Oxidative phosphorylation(UK , US : or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation, is the metabolic pathway in which Cell (biology), cells use enzymes to Redox, oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order ...

. In ''R. pachyptila'' the production of hydrogen sulfide starts after 24h of hypoxia. In order to avoid physiological damage some animals, including ''Riftia'' ''pachyptila'' are able to bind H2S to haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobi ...

in the blood to eventually expel it in the surrounding environment.

Carbon fixation and organic carbon assimilation

Unlike metazoans, which respire carbon dioxide as a waste product, ''R. pachyptila''-symbiont association has a demand for a net uptake of CO2 instead, as acnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

n-symbiont associations.

Ambient deep-sea water contains an abundant amount of inorganic carbon in the form of bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial bioche ...

HCO3−, but it is actually the chargeless form of inorganic carbon, CO2, that is easily diffusible across membranes. The low partial pressures of CO2 in the deep-sea environment is due to the seawater alkali

In chemistry, an alkali (; from the Arabic word , ) is a basic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a soluble base has a pH greater than 7.0. The a ...

ne pH and the high solubility of CO2, yet the pCO2 of the blood of ''R. pachyptila'' may be as much as two orders of magnitude greater than the pCO2 of deep-sea water.

CO2 partial pressures are transferred to the vicinity of vent fluids due to the enriched inorganic carbon content of vent fluids and their lower pH. CO2 uptake in the worm is enhanced by the higher pH of its blood (7.3–7.4), which favors the bicarbonate ion and thus promotes a steep gradient across which CO2 diffuses into the vascular blood of the plume. The facilitation of CO2 uptake by high environmental pCO2 was first inferred based on measures of elevated blood and coelomic fluid pCO2 in tubeworms, and was subsequently demonstrated through incubations of intact animals under various pCO2 conditions.

Once CO2 is fixed by the symbionts, it must be assimilated by the host tissues. The supply of fixed carbon to the host is transported via organic molecules from the trophosome in the hemolymph, but the relative importance of translocation and symbiont digestion is not yet known. Studies proved that within 15 min, the label first appears in symbiont-free host tissues, and that indicates a significant amount of release of organic carbon immediately after fixation. After 24 h, labeled carbon is clearly evident in the epidermal tissues of the body wall. Results of the pulse-chase autoradiograph

An autoradiograph is an image on an X-ray film or nuclear emulsion produced by the pattern of decay emissions (e.g., beta particles or gamma rays) from a distribution of a radioactive substance. Alternatively, the autoradiograph is also availab ...

ic experiments were also evident with ultrastructural evidence for digestion of symbionts in the peripheral regions of the trophosome lobules.

Sulfide acquisition

In deep-sea hydrothermal vents,sulfide

Sulfide (also sulphide in British English) is an inorganic anion of sulfur with the chemical formula S2− or a compound containing one or more S2− ions. Solutions of sulfide salts are corrosive. ''Sulfide'' also refers to large families o ...

and oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

are present in different areas. Indeed, the reducing fluid of hydrothermal vents is rich in sulfide, but poor in oxygen, whereas sea water is richer in dissolved oxygen. Moreover, sulfide is immediately oxidized by dissolved oxygen to form partly, or totally, oxidized sulfur compounds like thiosulfate

Thiosulfate ( IUPAC-recommended spelling; sometimes thiosulphate in British English) is an oxyanion of sulfur with the chemical formula . Thiosulfate also refers to the compounds containing this anion, which are the salts of thiosulfuric acid, ...

(S2O32-) and ultimately sulfate

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many ...

(SO42-), respectively less, or no longer, usable for microbial oxidation metabolism. This causes the substrates to be less available for microbial activity, thus bacteria are constricted to compete with oxygen to get their nutrients. In order to avoid this issue, several microbes have evolved to make symbiosis

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction, between two organisms of different species. The two organisms, termed symbionts, can fo ...

with eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

hosts. In fact, ''R. pachyptila'' is able to cover the oxic and anoxic

Anoxia means a total depletion in the level of oxygen, an extreme form of hypoxia or "low oxygen". The terms anoxia and hypoxia are used in various contexts:

* Anoxic waters, sea water, fresh water or groundwater that are depleted of dissolved ox ...

areas to get both sulfide and oxygen thanks to its hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobin ...

that can bind sulfide reversibly and apart from oxygen by functional binding sites determined to be zinc ions embedded in the A2 chains of the hemoglobins. and then transport it to the trophosome, where bacterial metabolism can occur. It has also been suggested that cysteine

Cysteine (; symbol Cys or C) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine enables the formation of Disulfide, disulfide bonds, and often participates in enzymatic reactions as ...

residues are involved in this process.

Symbiont acquisition

The acquisition of a symbiont by a host can occur in these ways: *Environmental transfer (symbiont acquired from a free-living population in the environment) * Vertical transfer (parents transfer symbiont to offspring via eggs) * Horizontal transfer (hosts that share the same environment) Evidence suggests that ''R. pachyptila'' acquires its symbionts through its environment. In fact,16S rRNA

16S ribosomal RNA (or 16Svedberg, S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome (SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The genes coding for it are referred to as ...

gene analysis showed that vestimentiferan tubeworms belonging to three different genera: ''Riftia'', ''Oasisia'', and ''Tevnia'', share the same bacterial symbiont phylotype.

This proves that ''R. pachyptila'' takes its symbionts from a free-living bacterial population in the environment. Other studies also support this thesis, because analyzing ''R. pachyptila'' eggs, 16S rRNA belonging to the symbiont was not found, showing that the bacterial symbiont is not transmitted by vertical transfer.

Another proof to support the environmental transfer comes from several studies conducted in the late 1990s. PCR was used to detect and identify a ''R. pachyptila'' symbiont gene whose sequence was very similar to the ''fliC'' gene that encodes some primary protein subunits (flagellin

Flagellins are a family of proteins present in flagellated bacteria which arrange themselves in a hollow cylinder to form the filament in a bacterial flagellum. Flagellin has a mass on average of about 40,000 daltons. Flagellins are the princi ...

) required for flagellum

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

synthesis. Analysis showed that ''R. pachyptila'' symbiont has at least one gene needed for flagellum synthesis. Hence, the question arose as to the purpose of the flagellum. Flagellar motility would be useless for a bacterial symbiont transmitted vertically, but if the symbiont came from the external environment, then a flagellum would be essential to reach the host organism and to colonize it. Indeed, several symbionts use this method to colonize eukaryotic hosts.

Thus, these results confirm the environmental transfer of ''R. pachyptila'' symbiont.

Reproduction

''R. pachyptila'' is adioecious

Dioecy ( ; ; adj. dioecious, ) is a characteristic of certain species that have distinct unisexual individuals, each producing either male or female gametes, either directly (in animals) or indirectly (in seed plants). Dioecious reproduction is ...

vestimentiferan. Individuals of this species are sessile and are found clustered together around deep-sea hydrothermal vents of the East Pacific Rise and the Galapagos Rift. The size of a patch of individuals surrounding a vent is within the scale of tens of metres.

The male's spermatozoa

A spermatozoon (; also spelled spermatozoön; : spermatozoa; ) is a motile sperm cell (biology), cell produced by male animals relying on internal fertilization. A spermatozoon is a moving form of the ploidy, haploid cell (biology), cell that is ...

are thread-shaped and are composed of three distinct regions: the acrosome (6 μm), the nucleus (26 μm) and the tail (98 μm). Thus, the single spermatozoa is about 130 μm long overall, with a diameter of 0.7 μm, which becomes narrower near the tail area, reaching 0.2 μm. The sperm is arranged into an agglomeration of around 340–350 individual spermatozoa that create a torch-like shape. The cup part is made up of acrosomes and nucleus, while the handle is made up by the tails. The spermatozoa in the package are held together by fibril

Fibrils () are structural biological materials found in nearly all living organisms. Not to be confused with fibers or protein filament, filaments, fibrils tend to have diameters ranging from 10 to 100 nanometers (whereas fibers are micro to ...

s. Fibrils also coat the package itself to ensure cohesion.

The large ovaries

The ovary () is a gonad in the female reproductive system that produces ova; when released, an ovum travels through the fallopian tube/oviduct into the uterus. There is an ovary on the left and the right side of the body. The ovaries are endocr ...

of females run within the gonocoel along the entire length of the trunk and are ventral to the trophosome. Eggs at different maturation stages can be found in the middle area of the ovaries, and depending on their developmental stage, are referred to as: oogonia, oocyte

An oocyte (, oöcyte, or ovocyte) is a female gametocyte or germ cell involved in reproduction. In other words, it is an immature ovum, or egg cell. An oocyte is produced in a female fetus in the ovary during female gametogenesis. The female ger ...

s, and follicular cells. When the oocytes mature, they acquire protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

and lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

yolk granules.

Males release their sperm into sea water. While the released agglomerations of spermatozoa, referred to as spermatozeugmata, do not remain intact for more than 30 seconds in laboratory conditions, they may maintain integrity for longer periods of time in specific hydrothermal vent conditions. Usually, the spermatozeugmata swim into the female's tube. Movement of the cluster is conferred by the collective action of each spermatozoon moving independently. Reproduction has also been observed involving only a single spermatozoon reaching the female's tube. Generally, fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give ...

in ''R. pachyptila'' is considered internal. However, some argue that, as the sperm is released into sea water and only afterwards reaches the eggs in the oviduct

The oviduct in vertebrates is the passageway from an ovary. In human females, this is more usually known as the fallopian tube. The eggs travel along the oviduct. These eggs will either be fertilized by spermatozoa to become a zygote, or will dege ...

s, it should be defined as internal-external.

''R. pachyptila'' is completely dependent on the production of volcanic gas

Volcanic gases are gases given off by active (or, at times, by dormant) volcanoes. These include gases trapped in cavities (Vesicular texture, vesicles) in volcanic rocks, dissolved or dissociated gases in magma and lava, or gases emanating from ...

es and the presence of sulfide

Sulfide (also sulphide in British English) is an inorganic anion of sulfur with the chemical formula S2− or a compound containing one or more S2− ions. Solutions of sulfide salts are corrosive. ''Sulfide'' also refers to large families o ...

-oxidizing bacteria. Therefore, its metapopulation distribution is profoundly linked to volcanic and tectonic

Tectonics ( via Latin ) are the processes that result in the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. The field of ''planetary tectonics'' extends the concept to other planets and moons.

These processes ...

activity that create active hydrothermal vent sites with a patchy and ephemeral

Ephemerality (from the Greek word , meaning 'lasting only one day') is the concept of things being transitory, existing only briefly. Academically, the term ephemeral constitutionally describes a diverse assortment of things and experiences, fr ...

distribution. The distance between active sites along a rift or adjacent segments can be very high, reaching hundreds of km. This raises the question regarding larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

l dispersal. ''R. pachytpila'' is capable of larval dispersal across distances of 100 to 200 km and cultured larvae show to be viable for 38 days. Though dispersal is considered to be effective, the genetic variability

Genetic variability is either the presence of, or the generation of, genetic differences. It is defined as "the formation of individuals differing in genotype, or the presence of genotypically different individuals, in contrast to environmentally ...

observed in ''R. pachyptila'' metapopulation is low compared to other vent species. This may be due to high extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

events and colonization

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

events, as ''R. pachyptila'' is one of the first species to colonize a new active site.

The endosymbiont

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

s of ''R. pachyptila'' are not passed to the fertilized eggs during spawning

Spawn is the Egg cell, eggs and Spermatozoa, sperm released or deposited into water by aquatic animals. As a verb, ''to spawn'' refers to the process of freely releasing eggs and sperm into a body of water (fresh or marine); the physical act is ...

, but are acquired later during the larval stage of the vestimentiferan worm. ''R. pachyptila'' plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

ic larvae that are transported through sea-bottom currents until they reach active hydrothermal vents sites, are referred to as trophocores. The trophocore stage lacks endosymbionts, which are acquired once larvae settle in a suitable environment and substrate. Free-living bacteria found in the water column are ingested randomly and enter the worm through a ciliated opening of the branchial plume. This opening is connected to the trophosome through a duct that passes through the brain. Once the bacteria are in the gut, the ones that are beneficial to the individual, namely sulfide- oxidizing strains are phaghocytized by epithelial

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial ( mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of man ...

cells found in the midgut are then retained. Bacteria that do not represent possible endosymbionts are digested. This raises questions as to how ''R. pachyptila'' manages to discern between essential and nonessential bacterial strains. The worm's ability to recognise a beneficial strain, as well as preferential host-specific infection by bacteria have been both suggested as being the drivers of this phenomenon.

Growth rate and age

''R. pachyptila'' has the fastest growth rate of any known marine invertebrate. These organisms have been known to colonize a new site, grow to sexual maturity, and increase in length to 4.9 feet (1.5 m) in less than two years. Because of the peculiar environment in which ''R. pachyptila'' thrives, thisspecies

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

differs greatly from other deep-sea species that do not inhabit hydrothermal vents sites; the activity of diagnostic enzymes for glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvic acid, pyruvate and, in most organisms, occurs in the liquid part of cells (the cytosol). The Thermodynamic free energy, free energy released in this process is used to form ...

, citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reaction, biochemical reactions that release the energy stored in nutrients through acetyl-Co ...

and transport of electrons in the tissues of ''R. pachyptila'' is very similar to the activity of these enzymes in the tissues of shallow-living animals. This contrasts with the fact that deep-sea species usually show very low metabolic rates, which in turn suggests that low water temperature and high pressure in the deep sea do not necessarily limit the metabolic rate of animals and that hydrothermal vents sites display characteristics that are completely different from the surrounding environment, thereby shaping the physiology and biological interactions of the organisms living in these sites.

See also

*Siboglinidae

Siboglinidae is a family (biology), family of polychaete Annelida, annelid worms whose members made up the former phylum, phyla Pogonophora and Vestimentifera (the giant tube worms). The family is composed of around 100 species of vermiform creatu ...

* '' Lamellibrachia''

* List of long-living organisms

This is a list of the longest-living biological organisms: the individual(s) (or in some instances, clones) of a species with the longest natural maximum life spans. For a given species, such a designation may include:

# The oldest known indiv ...

* Maximum life span

* Pompeii worm

* Chemosynthesis

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrog ...

References

External links

*Giant Tube Worm page at the Smithsonian

Podcast on Giant Tube Worm at the Encyclopedia of Life

* http://www.seasky.org/monsters/sea7a1g.html

* https://web.archive.org/web/20090408022512/http://www.ocean.udel.edu/deepsea/level-2/creature/tube.html {{DEFAULTSORT:Giant Tube Worm Polychaetes Annelids of the Pacific Ocean Animals described in 1981 Chemosynthetic symbiosis Animals living on hydrothermal vents