Richard Reynolds (ironmaster) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard Reynolds (November 1735 – 10 September 1816) was an

Richard Reynolds was born in

Richard Reynolds was born in

ironmaster

An ironmaster is the manager, and usually owner, of a forge or blast furnace for the processing of iron. It is a term mainly associated with the period of the Industrial Revolution, especially in Great Britain.

The ironmaster was usually a larg ...

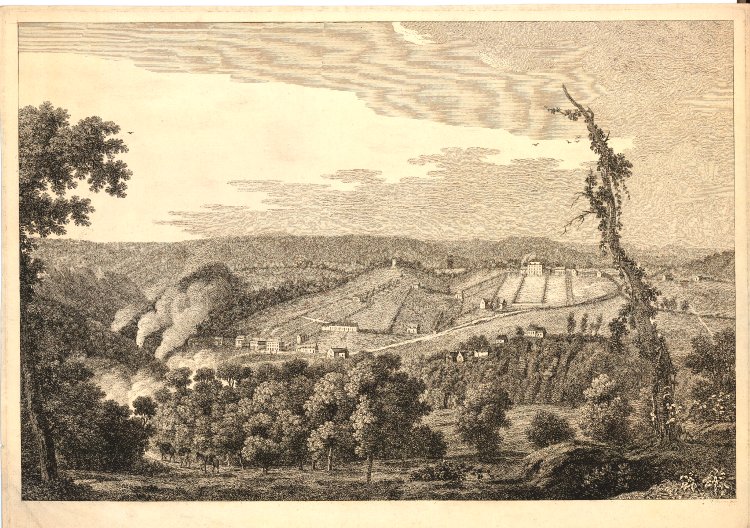

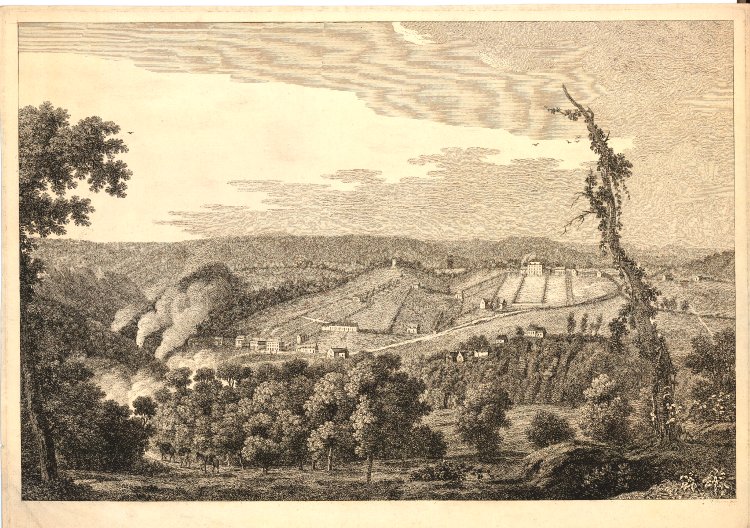

, a partner in the ironworks in Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a town in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called The Gorge, Shro ...

, Shropshire, at a significant time in the history of iron production. He was a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

and philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

.

Early career

Richard Reynolds was born in

Richard Reynolds was born in Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

in 1735, the only son of Richard, an iron merchant, and wife Jane. He was great-grandson of Michael Reynolds of Faringdon

Faringdon is a historic market town in the Vale of White Horse, Oxfordshire, England, south-west of Oxford, north-west of Wantage and east-north-east of Swindon. Its views extend to the River Thames in the north and the highest ground visib ...

, Berkshire, an early Quaker. After his education he was apprenticed in 1749 to William Fry, a grocer in Bristol. After serving the apprenticeship in 1756, he was sent on business to Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a town in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called The Gorge, Shro ...

, and there he became a friend of Abraham Darby II

Abraham Darby, in his lifetime called Abraham Darby the Younger, referred to for convenience as Abraham Darby II (12 May 1711 – 31 March 1763) was the second man of that name in an English Quaker family that played an important role in the ea ...

. He married Darby's daughter, Hannah, at Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is sited on the River Severn, northwest of Wolverhampton, west of Telford, southeast of Wrexham and north of Hereford. At the 2021 United ...

on 20 May 1757.

He was in charge of Abraham Darby's ironworks at Ketley, near Coalbrookdale, and in 1762 he bought a half share in the Ketley works. When his father-in-law died in 1763, he moved to Coalbrookdale and took charge of the works there, until Abraham Darby III

Abraham Darby III (24 April 1750 – 1789) was an English ironmaster and Quaker. He was the third man of that name in several generations of an English Quaker family that played a pivotal role in the Industrial Revolution.

Life

Abraham Darby ...

came of age in 1768; he then returned to managing the Ketley works.''The Coalbrookdale Ironworks: a short history''. Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, 1975.

Innovations at Coalbrookdale

Reynolds did much to develop and extend the Coalbrookdale works. Under his direction thecylinders

A cylinder () has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infinite ...

of early steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

s were cast there.

New refining process

In 1766 a patent for refining iron was taken out under his auspices by theCranege brothers

Thomas and George Cranege (also spelled ''Cranage''), who worked in the ironworking industry in England in the 1760s, are notable for introducing a new method of producing wrought iron from pig iron.

Experiment of 1766

The process of converting p ...

; Thomas Cranege worked at a forge at Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the United Kingd ...

and his brother George worked at Coalbrookdale. The new process of converting pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

into wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

used a reverbatory furnace

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgy, metallurgical or process Metallurgical furnace, furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term ''reverberation'' is use ...

powered by coal, instead of the charcoal used in a finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and decarburization, removing carbon from the molten cast iron through Redo ...

, and so was not dependent on a supply of wood. Reynolds saw its importance, and it seems to have been practically carried out at Coalbrookdale. The process was later developed by Henry Cort

Henry Cort (c. 1740 – 23 May 1800) was an English ironware producer who was formerly a Navy pay agent. During the Industrial Revolution in England, Cort began refining iron from pig iron to wrought iron (or bar iron) using innovative productio ...

.

Iron rails

In 1767 he replaced the wooden rails, for the railways taking iron and coal from one part of the works to another, with cast iron rails; it is thought this was the first time iron rails were used for transportation.Later years

From 1768, when Abraham Darby III took over the management, Reynolds remained associated with the concern, and greatly improved the works in the interests of his workpeople. In 1785 he joined in forming the United Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain, and himself represented the iron trade. In 1788 he and others obtained an Act of Parliament for the construction of theShropshire Canal

The Shropshire Canal was a tub boat canal built to supply coal, ore and limestone to the industrial region of east Shropshire, England, that adjoined the River Severn at Coalbrookdale. It ran from a junction with the Donnington Wood Canal asce ...

, a canal to supply coal and iron ore to the works. About 1789 he retired from business. By this time the works in the Coalbrookdale area, with associated coal and iron ore mines, were one of the largest iron-making concerns in the country.

In April 1804 he settled in Bristol. Determining to "be his own executor," Reynolds devoted himself to dispensing charity unostentatiously and through private almoner

An almoner () is a chaplain or church officer who originally was in charge of distributing money to the deserving poor. The title ''almoner'' has to some extent fallen out of use in English, but its equivalents in other languages are often used f ...

s, but on a large scale. It is believed that he usually gave away at least £10,000 a year, besides giving £10,500 to trustees to invest in lands in Monmouthshire

Monmouthshire ( ; ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county in the South East Wales, south east of Wales. It borders Powys to the north; the English counties of Herefordshire and Gloucestershire to the north and east; the Severn Estuary to the s ...

for the benefit of Bristol charities.

He died while on a visit to Cheltenham

Cheltenham () is a historic spa town and borough adjacent to the Cotswolds in Gloucestershire, England. Cheltenham became known as a health and holiday spa town resort following the discovery of mineral springs in 1716, and claims to be the mo ...

for his health on 10 September 1816 aged 80, and was buried at the Friars, Bristol, on 17 September.

By his first wife, who died in 1762, Reynolds had a daughter, Hannah Mary, and a son William Reynolds (1758–1803), who became a manager of the works and collieries in Ketley and the neighbourhood. By his second wife Rebecca, who predeceased him, he had three sons, Michael, Richard, and Joseph.

References

Attribution * Further reference * Rathbone, Hannah Mary, ''Letters of Richard Reynolds, with a Memoir of his Life'' (London, Charles Gilpin, 1852) authored by his granddaughter.External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Reynolds, Richard 1735 births 1816 deaths Businesspeople from Bristol English ironmasters English Quakers 18th-century Quakers People of the Industrial Revolution