Repatriation and reburial of human remains on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The repatriation and reburial of human remains is a current issue in

Ishi had explicit wishes to be cremated intact. However, against these wishes, his body underwent an autopsy. His brain was removed and forgotten in a Smithsonian warehouse. Finally, in 2000, Ishi's brain had been found and returned to the Pit River tribe.

Ishi had explicit wishes to be cremated intact. However, against these wishes, his body underwent an autopsy. His brain was removed and forgotten in a Smithsonian warehouse. Finally, in 2000, Ishi's brain had been found and returned to the Pit River tribe.

"The Kennewick Man Finally Freed to Share His Secrets"

'' Smithsonian''. Retrieved November 8, 2014. which became the subject of a controversial nine-year court case between the

Aboriginal remains repatriation

(Australia)

Book reviews of Scarre & Scarre and Vitelli and Colwell

archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

and museum management on the holding of human remains. Between the descendant-source community and anthropologists, there are a variety of opinions on whether or not the remains should be repatriated. There are numerous case studies across the globe of human remains that have been or still need to be repatriated.

Perspectives

The repatriation and reburial of human remains is considered controversial within archaeological ethics. Often, descendants and people from the source community of the remains desire their return. Meanwhile, Anthropologists, scientists who study the remains for research purposes, may have differing opinions. Some anthropologists feel it's necessary to keep the remains in order to improve the field and historical understanding. Others feel that repatriation is necessary in order to respect the descendants.Descendant and source community perspective

The descendants and source community of the remains commonly advocate for repatriation. This may be due to human rights and spiritual beliefs. For example, Henry Atkinson of the Yorta Yorta Nation describes the history that motivates this advocacy. He explains that his ancestors were invaded and massacred by the Europeans. After this, their remains were plundered and "collected like one collects stamps." Finally, the ancestors were shipped away as specimen to be studied. This made the Yorta Yorta people feel subhuman—like animals and decorative trinkets. Atkinson explains that repatriation will help to soothe the generational pain that resulted from the massacres and collections. Additionally, there is a repeated theme that descendants have a spiritual connection to their ancestors. Many Indigenous people feel that resting places are sacred and freeing for their ancestors. However, ancestors who are boxed in foreign institutions are trapped and unable to rest. This can cause tremendous distress for their descendants. Some descendants feel that the ancestors can only be free and rest in peace after they are repatriated. This is a similar sentiment withinBotswana

Botswana, officially the Republic of Botswana, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory part of the Kalahari Desert. It is bordered by South Africa to the sou ...

. Connie Rapoo, a Botswana native, explained the importance of ancestors being repatriated. Rapoo explains that people must return to their home for a sense of kinship and belonging. If they're not returned, the ancestors' souls may wander restlessly. They may even transform into evil spirits who haunt the living. They believe repatriation helps to grant peace to both ancestors and descendants.

Historical trauma

The argument for repatriation is further complicated by the historical trauma that many Indigenous people experience. Historical trauma refers to the emotional trauma experienced by ancestors that is passed onto generations today. Historically, Indigenous people have experienced massacres and the loss of their children to residential schools. This immense grief is also shared and felt by descendants. Historical trauma is perpetuated by the status of ancestors being boxed away and studied. Some Indigenous people believe that the pain will be alleviated when their ancestors are repatriated and free.Anthropologists' perspective

Anthropologists have divided opinions on supporting or rejecting repatriation.Anti-repatriation

Some anthropologists feel that repatriation will harm anthropological research and understanding. For example, Elizabeth Weiss and James W. Springer believe that repatriation is the loss of collections, and thereby the "loss of data." This is due to the nature of Western science and epistemology. To improve scientific accuracy, biological anthropologists test new methods and retest old methods on collections. Weiss and Springer describe Indigenous remains as the most abundant and significant resource to the field. They believe that reburial prevents the improvement and legitimacy of anthropological methods. According to some anthropologists, this in turn prevents many important findings. Studying human remains may reveal information on human pre-history. It helps anthropologists learn how humans evolved and came to be. Additionally, the study of human remains reveals numerous characteristics about ancient populations. It may reveal population's health status, diseases, labor activities, and violence they experienced. Anthropology may identify cultural practices such as the cranial modification. It can also help populations today. Specifically, anthropologists have found signs of earlyarthritis

Arthritis is a general medical term used to describe a disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, Joint effusion, swelling, and decreased range of motion of ...

on ancient remains. They believe this identification is beneficial for the early detection of arthritis

Arthritis is a general medical term used to describe a disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, Joint effusion, swelling, and decreased range of motion of ...

in people today.

Some anthropologists feel that these discoveries will be lost with the reburial of human remains.

Pro-repatriation

Not all anthropologists are anti-repatriation. Rather, some feel that repatriation is an ethical necessity that the field has been neglecting. Sian Halcrow et al. explains that anthropology has a history of racist double standards. Specifically, White remains within archaeological and disaster cases are reburied in coffins. Meanwhile, Indigenous and non-White remains are infamously boxed and studied. She notes that the unethical sourcing and study of remains without permission is considered a civil rights violation. Halcrow et al. proposes that the repatriation is the bare minimum request to have one's remains treated the same as others. Some anthropologists view repatriation—not as a privilege—but as a human right that had been refused to people of color for too long. They don't view repatriation as the loss or downfall of anthropology. Rather, they feel that repatriation is the start of anthropology moving toward more ethical methods.Health considerations

Some of the remains were preserved with pesticides that are now known to be harmful to human health.Case studies

Australia

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ancestral remains were removed from graves, burial sites, hospitals, asylums, and prisons from the 19th century through to the late 1940s. Most of those which ended up in other countries are in the United Kingdom, with many also in Germany, France, and other European countries, as well as in the US. Official figures do not reflect the true state of affairs, with many in private collections and small museums. More than 10,000 corpses or part-corpses were probably taken to the UK alone. Australia has no laws directly governing repatriation, but the Australian Government established its Policy on Indigenous Repatriation in 2011. it is run by the Office for the Arts. This programme "supports the repatriation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ancestral remains and secret sacred objects, which contributes to healing and reconciliation" and assists community representatives work towards repatriation of remains in various ways. In July 2020, the government promised funding toAIATSIS

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), established as the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS) in 1964, is an independent Australian Government statutory authority. It is a collecting, ...

to implement the Return of Cultural Heritage Initiative over four years. The government website reported that as of March 2025, 1741 Indigenous ancestors' remains had been repatriated from other countries. In April 2025 ABC News ABC News most commonly refers to:

* ABC News (Australia), a national news service of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

* ABC News (United States), a news-gathering and broadcasting division of the American Broadcasting Company

ABC News may a ...

reported that over 1,775 remains had been repatriated. The majority of these – 1,300 – had been sent from collecting institutions and private holdings in the UK.

In March 2020, a documentary titled ''Returning Our Ancestors'' was released by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council based on the book ''Power and the Passion: Our Ancestors Return Home'' (2010) by Shannon Faulkhead and Uncle Jim Berg, partly narrated by award-winning musician Archie Roach

Archibald William Roach (8 January 1956 – 30 July 2022) was an Australian (Gunditjmara and Western Bundjalung people, Bundjalung) singer-songwriter and Aboriginal Australian, Aboriginal activist. Often referred to as "Uncle Archie", Roach wa ...

. It was developed primarily as a resource for secondary schools in the state of Victoria, to help develop an understanding of Aboriginal history and culture by explaining the importance of ancestral remains.

The Queensland Museum

The Queensland Museum Kurilpa is the state museum of Queensland, funded by the government, and dedicated to natural history, cultural heritage, science and human achievement. The museum currently operates from its headquarters and general museu ...

's program of returning and reburying ancestral remains which had been collected by the museum between 1870 and 1970 has been under way since the 1970s. As of November 2018, the museum had the remains of 660 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people stored in their "secret sacred room" on the fifth floor.

In March 2019, 37 sets of Australian Aboriginal ancestral remains were set to be returned, after the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

officially gave back the remains by means of a solemn ceremony. The remains would be looked after by the South Australian Museum and the National Museum of Australia

The National Museum of Australia (NMA), in the national capital Canberra, preserves and interprets Australia's social history, exploring the key issues, people and events that have shaped the nation. It was formally established by the ''Nation ...

until such time as reburial could take place.

In April 2019, work began to return more than 50 ancestral remains from five different German institutes, starting with a ceremony at the Five Continents Museum in Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

.

The South Australian Museum reported in April 2019 that it had more than 4,600 Old People in storage, awaiting reburial. Whilst many remains had been shipped overseas by its 1890s director Edward C. Stirling many more were the result of land clearing, construction projects or members of the public. With a recent change in policy at the museum, a dedicated Repatriation Officer would implement a program of repatriation.

A notorious South Australian case in 1903 involved the grave-robbing of Ngarrindjeri

The Ngarrindjeri people are the traditional Aboriginal Australian people of the lower Murray River, eastern Fleurieu Peninsula, and the Coorong of the southern-central area of the state of South Australia. The term ''Ngarrindjeri'' means "belo ...

man Tommy Walker by the SA state coroner, Dr William Ramsay Smith. This exposed a broader, hidden trade in mainly Aboriginal human remains by medical and scientific institutions to supply UK institutions. Public outrage over the scandal highlighted deep cultural violations and contributed to a struggle for repatriation that would span more than a century.

In April 2019, the skeletons of 14 Yawuru and Karajarri

The Karajarri, also spelt Garadjara, are an Aboriginal Australian people of Western Australia. They live south-west of the Kimberleys in the northern Pilbara region, predominantly between the coastal area and the Great Sandy Desert. They now mo ...

people which had been sold by a wealthy Broome pastoralist and pearler to a museum in Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

in 1894 were brought home to Broome, in Western Australia. The remains, which had been stored in the Grassi Museum of Ethnology in Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

, showed signs of head wounds and malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients which adversely affects the body's tissues a ...

, a reflection of the poor conditions endured by Aboriginal people forced to work on the pearling boats in the 19th century. The Yawuru and Karajarri people were still in negotiations with the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

to enable the release of the skull of the warrior known as Gwarinman.

On 1 August 2019, the remains of 11 Kaurna people which had been returned from the UK were laid to rest at a ceremony led by elder Jeffrey Newchurch at Kingston Park Coastal Reserve, south of the city of Adelaide

Adelaide ( , ; ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital and most populous city of South Australia, as well as the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. The name "Adelaide" may refer to ei ...

.

In November 2021, the South Australian Museum apologised to the Kaurna people for having taken their ancestors' remains, and buried 100 of them a new site at Smithfield Memorial Park, donated by Adelaide Cemeteries. The memorial site is in the shape of the Kaurna shield, to protect the ancestors now buried there.

In mid-April 2025, the Natural History Museum handed over the remains of a further 36 ancestors in a formal ceremony at the institution.

New Zealand

Te Papa

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is New Zealand's national museum and is located in Wellington. Usually known as Te Papa (Māori language, Māori for 'Waka huia, the treasure box'), it opened in 1998 after the merging of the Nation ...

, the national museum in Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

was mandated by the government in 2003 to manage the Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation Programme (KARP) to repatriate Māori and Moriori

The Moriori are the first settlers of the Chatham Islands ( in Moriori language, Moriori; in Māori language, Māori). Moriori are Polynesians who came from the New Zealand mainland around 1500 AD, which was close to the time of the ...

remains (). Te Papa researches the provenance of remains and negotiates with overseas institutions for their return. Once returned to New Zealand the remains are not accessioned by Te Papa as the museum arranges their return to their iwi

Iwi () are the largest social units in New Zealand Māori society. In Māori, roughly means or , and is often translated as "tribe". The word is both singular and plural in the Māori language, and is typically pluralised as such in English.

...

(tribe). Remains have been repatriated from Argentina, Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United States and the United Kingdom. Between 2003 and 2015 the return of 355 remains was negotiated by KARP.

Heritage New Zealand

Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga (initially the National Historic Places Trust and then, from 1963 to 2014, the New Zealand Historic Places Trust; in ) is a Crown entity that advocates for the protection of Archaeology of New Zealand, ancest ...

has a policy on repatriation. In 2018 the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

The Ministry for Culture and Heritage (MCH; ) is the department of the New Zealand Government responsible for supporting the Creative New Zealand, arts, Culture of New Zealand, culture, New Zealand Historic Places Trust, built heritage, Sport Ne ...

published a report on ''Human Remains in New Zealand Museums'' and The New Zealand Repatriation Research Network was established for museums to work together to research the provenance of remains and assist repatriation. Museums Aotearoa adopted a National Repatriation Policy in 2021.

Canada

During the 1800s, Canada established numerous residential schools for Indigenous youth. This was an act ofcultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's Dominant culture, majority group or fully adopts the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group. The melting pot model is based on this ...

and genocide where many of the children died and were buried at these schools. In the 21st century, these mass graves are being discovered and repatriated. Two of the most well-known mass graves includes those at the Kamloops Indian Residential School

The Kamloops Indian Residential School was part of the Canadian Indian residential school system. Located in Kamloops, British Columbia, it was once the largest residential school in Canada, with its enrolment peaking at 500 in the 1950s. The sc ...

(over 200 Indigenous children buried) and the Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada. It is bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and to the south by the ...

Residential School (over 700 Indigenous children buried). Canada is working on searching for and repatriating these graves.

France

During the French colonization of Algeria, 24 Algerians fought the colonial forces in 1830 and in an 1849 revolt. They were decapitated and their skulls were taken to France as trophies. In 2011, Ali Farid Belkadi, an Algerian historian, discovered the skulls at the Museum of Man in Paris and alerted Algerian authorities that consequently launched the formal repatriation request, the skulls were returned in 2020. Between the remains were those of revolt leader Sheikh Bouzian, who was captured in 1849 by the French, shot and decapitated, and the skull of resistance leader Mohammed Lamjad ben Abdelmalek, also known as Cherif Boubaghla (the man with the mule).Germany

In 2023 seven German museums and universities returned Māori andMoriori

The Moriori are the first settlers of the Chatham Islands ( in Moriori language, Moriori; in Māori language, Māori). Moriori are Polynesians who came from the New Zealand mainland around 1500 AD, which was close to the time of the ...

remains to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is New Zealand's national museum and is located in Wellington. Usually known as Te Papa ( Māori for ' the treasure box'), it opened in 1998 after the merging of the National Museum of New Zealand ...

in New Zealand.

Austria

In 2022 theNatural History Museum, Vienna

The Natural History Museum Vienna () is a large natural history museum located in Vienna, Austria.

The NHM Vienna is one of the largest museums and non-university research institutions in Austria and an important center of excellence for all matt ...

returned the remains of about 64 Māori and Moriori

The Moriori are the first settlers of the Chatham Islands ( in Moriori language, Moriori; in Māori language, Māori). Moriori are Polynesians who came from the New Zealand mainland around 1500 AD, which was close to the time of the ...

people, collected by Andreas Reischek, to Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is New Zealand's national museum and is located in Wellington. Usually known as Te Papa ( Māori for ' the treasure box'), it opened in 1998 after the merging of the National Museum of New Zealand ...

in Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

, New Zealand.

Estonia

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Konstantin Päts was imprisoned in the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

after the Soviet invasion and occupation, where he died in 1956. In 1988, efforts began to locate Päts' remains in Russia. It was discovered that Päts had been granted a formal burial service, fitting of his office, near Kalinin (now Tver

Tver (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative centre of Tver Oblast, Russia. It is situated at the confluence of the Volga and Tvertsa rivers. Tver is located northwest of Moscow. Population:

The city is ...

). On 22 June 1990, his grave was dug up and the remains were reburied in Tallinn Metsakalmistu cemetery on 21 October 1990. In 2011, a commemorative cross was placed in Burashevo village, where Päts was once buried.

Ireland

The British anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon removed 13 skulls from a graveyard onInishmore

Inishmore ( , or ) is the largest of the Aran Islands in Galway Bay, off the west coast of Ireland. With an area of and a population of 820 (as of 2016), it is the second-largest island off the Irish coast (after Achill) and most populo ...

, and more skulls from Inishbofin, County Galway, and a graveyard in Ballinskelligs, County Kerry

County Kerry () is a Counties of Ireland, county on the southwest coast of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. It is bordered by two other countie ...

, as part of the Victorian-era study of "racial types". The skulls are still in storage at Trinity College Dublin

Trinity College Dublin (), officially titled The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, and legally incorporated as Trinity College, the University of Dublin (TCD), is the sole constituent college of the Unive ...

and their return to the cemeteries of origin has been requested, and the board of Trinity College has signalled its willingness to work with islanders to return the remains to the island.

On 24 February 2023, Trinity College Dublin confirmed that the human remains, including 13 skulls, in their possession would be returned to Inishbofin. This process is to formally begin in July 2023, with similar repatriation of remains at St. Finian's Bay and Inishmore to be started later in the year.

Spain

El Negro

The name " El Negro" refers to a dead African man who was taxidermized and displayed in the Darder Museum inBanyoles

Banyoles () is a city of 20,168 inhabitants (2021) located in the province of Girona in northeastern Catalonia, Spain.

The town is the capital of the Catalan ''comarca'' " Pla de l'Estany". Although an established industrial centre many of th ...

, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. His initial grave had been dug up around 1830. He was then taxidermized and dressed up with fur clothing and a spear. "El Negro" was sold to the Darder Museum and on display for over a century. It wasn't until 1992 when Banyoles was hosting the summer Olympics that people complained of the displayed and taxidermized human remains.

In 2000, "El Negro" was repatriated to Botswana

Botswana, officially the Republic of Botswana, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory part of the Kalahari Desert. It is bordered by South Africa to the sou ...

, which was believed to be his country of origin. Numerous Botswanans had gathered in the airport to greet "El Negro." However, there was controversy in the status and shipment of his remains. First, "El Negro" had arrived in a box, rather than a coffin. Botswanans felt this was dehumanizing. Second, "El Negro" was not returned as the whole body. Rather, only a stripped skull was sent to Botswana. The Spanish had skinned his body, claiming his skin and artifacts to be their property. Numerous Botswanas felt severely disrespected and offended by the objectification of "El Negro."

United Kingdom

The skeleton of the "Irish Giant" Charles Byrne (1761–1783) was on public display in the Hunterian Museum, London despite it being Byrne's express wish to be buried at sea. AuthorHilary Mantel

Dame Hilary Mary Mantel ( ; born Thompson; 6 July 1952 – 22 September 2022) was a British writer whose work includes historical fiction, personal memoirs and short stories. Her first published novel, ''Every Day Is Mother's Day'', was releas ...

called in 2020 for his remains to be returned to Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. It was removed from public display as part of redevelopment work in the late 2010s early 2020s although Byrne’s skeleton was retained in the museum collection to allow for future research.

Druids

The Neo-druidic movement is a modern religion, with some groups originating in the 18th century and others in the 20th century. They are generally inspired by either Victorian-era ideas of thedruids

A druid was a member of the high-ranking priestly class in ancient Celtic cultures. The druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no wr ...

of the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

, or later neopagan movements. Some practice ancestor veneration

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune of t ...

, and because of this may believe that they have a responsibility to care for the ancient dead where they now live. In 2006 Paul Davies requested that the Alexander Keiller Museum in Avebury, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

rebury their Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

human remains, and that storing and displaying them was "immoral and disrespectful". The National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

refused to allow reburial, but did allow for Neo-druids to perform a healing ritual in the museum.

The archaeological community has voiced criticism of the Neo-druids, making statements such as "no single modern ethnic group or cult should be allowed to appropriate our ancestors for their own agendas. It is for the international scientific community to curate such remains." An argument proposed by archaeologists is that:

Mr. Davies thanked English Heritage for their time and commitment given to the whole process and concluded that the dialogue used within the consultation focussed on museum retention and not reburial as requested.

Sarah Baartman

Sarah Baartman was aKhoikhoi

Khoikhoi (Help:IPA/English, /ˈkɔɪkɔɪ/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''KOY-koy'') (or Khoekhoe in Namibian orthography) are the traditionally Nomad, nomadic pastoralist Indigenous peoples, indigenous population of South Africa. They ...

woman from Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, South Africa, in the early 1800s. She was taken to Europe and advertised as a sexual "freak" for entertainment. She was known as the "Hottentot Venus." She died in 1815 and was dissected. Baartman's genitalia, brain, and skeleton were displayed in the Musee de l'Homme in Paris until repatriation to South Africa in 2002.

United States

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990, provides a process for museums and federal agencies to return certain cultural items such as human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, etc. to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Indian tribes andNative Hawaiian

Native Hawaiians (also known as Indigenous Hawaiians, Kānaka Maoli, Aboriginal Hawaiians, or simply Hawaiians; , , , and ) are the Indigenous peoples of Oceania, Indigenous Polynesians, Polynesian people of the Hawaiian Islands.

Hawaiʻi was set ...

organisations.

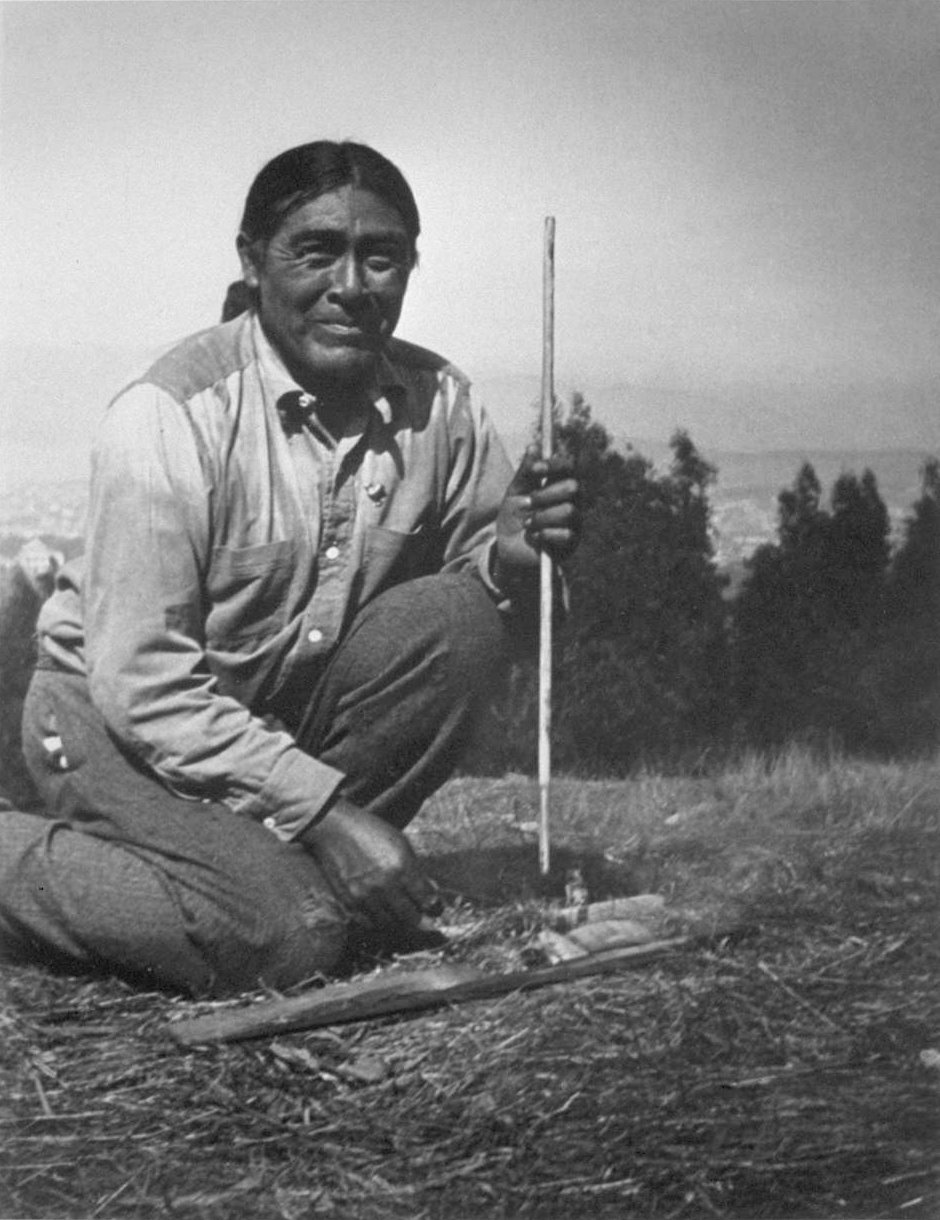

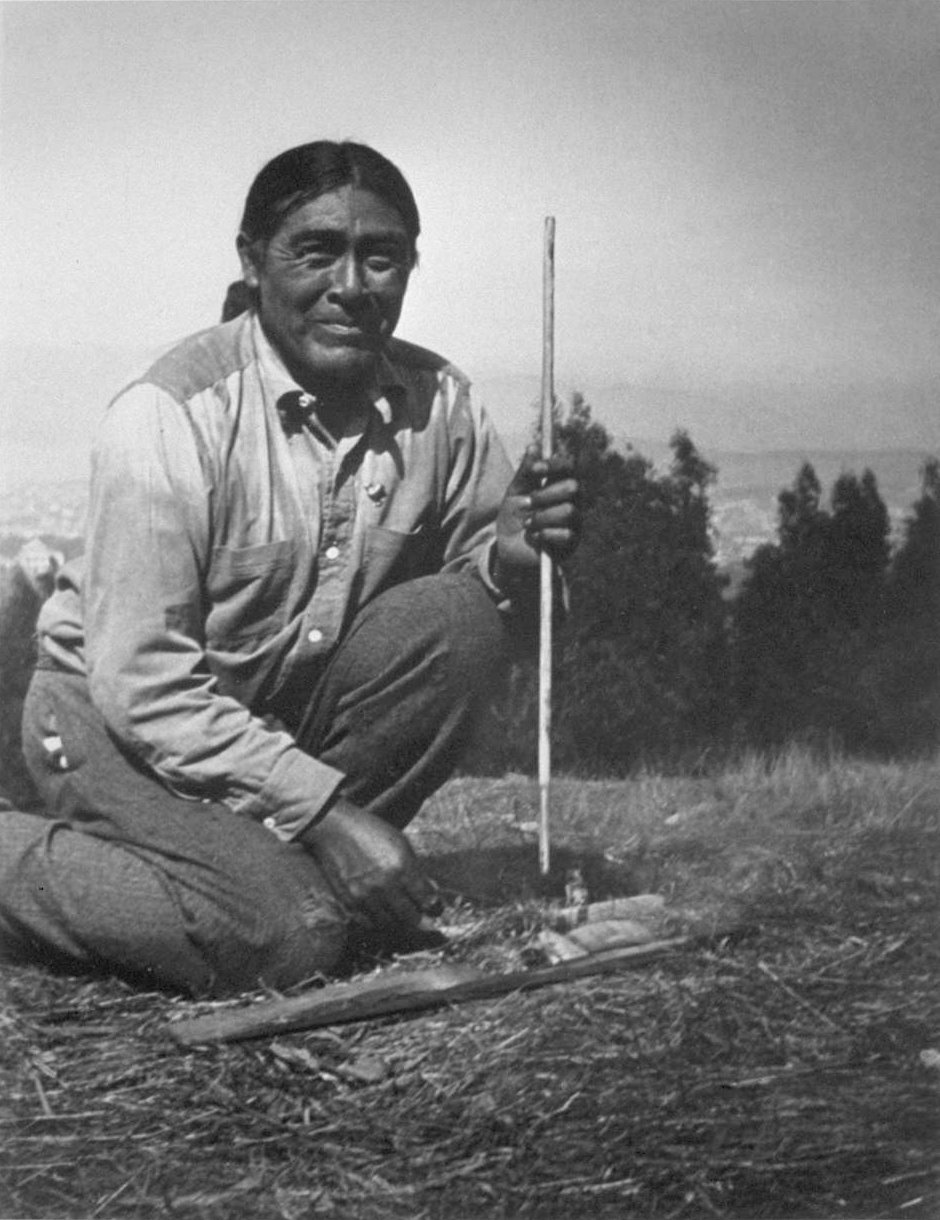

Ishi

Ishi was the last survivor of the Yahi Tribe in the early 1900s. He lived amongst and was studied by anthropologists for the rest of his life. During this time, he would tell stories of his tribe, give archery demonstrations, and be studied on his language. Ishi fell ill and died from tuberculosis in 1916. Ishi had explicit wishes to be cremated intact. However, against these wishes, his body underwent an autopsy. His brain was removed and forgotten in a Smithsonian warehouse. Finally, in 2000, Ishi's brain had been found and returned to the Pit River tribe.

Ishi had explicit wishes to be cremated intact. However, against these wishes, his body underwent an autopsy. His brain was removed and forgotten in a Smithsonian warehouse. Finally, in 2000, Ishi's brain had been found and returned to the Pit River tribe.

Kennewick Man

TheKennewick Man

Kennewick Man or Ancient One was a Native American man who lived during the early Holocene, whose skeletal remains were found in 1996 washed out on a bank of the Columbia River near Kennewick, Washington. Radiocarbon tests show the man lived a ...

is the name generally given to the skeletal remains of a prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

Paleoamerican man found on a bank

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

of the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

in Kennewick, Washington

Kennewick () is a city in Benton County, Washington, Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. It is located along the southwest bank of the Columbia River, just southeast of the confluence of the Columbia and Yakima ...

, United States, on 28 July 1996,Preston, Douglas (September 2014)"The Kennewick Man Finally Freed to Share His Secrets"

'' Smithsonian''. Retrieved November 8, 2014. which became the subject of a controversial nine-year court case between the

United States Army Corps of Engineers

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is the military engineering branch of the United States Army. A direct reporting unit (DRU), it has three primary mission areas: Engineer Regiment, military construction, and civil wo ...

, scientists, the Umatilla people and other Native American tribes who claimed ownership of the remains.

The remains of Kennewick Man were finally removed from the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture on 17 February 2017. The following day, more than 200 members of five Columbia Plateau

The Columbia Plateau is an important geology, geologic and geography, geographic region that lies across parts of the U.S. states of Washington (state), Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. It is a wide flood basalt plateau between the Cascade Range a ...

tribes were present at a burial of the remains.

Fiji

Mana

Mana may refer to:

Religion and mythology

* Mana (Oceanian cultures), the spiritual life force energy or healing power that permeates the universe in Melanesian and Polynesian mythology

* Mana (food), archaic name for manna, an edible substance m ...

, a complete human skeleton discovered in Moturiki in 2002, belonging to a Lapita

The Lapita culture is the name given to a Neolithic Austronesian people and their distinct material culture, who settled Island Melanesia via a seaborne migration at around 1600 to 500 BCE. The Lapita people are believed to have originated fro ...

woman that lived in or about 800 BCE, was formally re-buried at the archaelogical site where she was found in 2003, after being heavily studied for a year.

See also

* Repatriation (cultural heritage)Footnotes

References

Cited works

*Further reading

*Aboriginal remains repatriation

(Australia)

Book reviews of Scarre & Scarre and Vitelli and Colwell

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Repatriation And Reburial Of Human Remains * Neo-druidism Cultural heritage Art and culture law Indigenous rights Archaeology of death Archaeological collections Archaeological controversies